Highlights

-

A novel N-doped strategy of C2N3− in situ trimerization between the 2D MXene interlayers was first proposed.

-

The ultra-fast pseudocapacitive behavior of Ti3C2Tx/Na3TCM anode was managed and verified.

-

The as-fabricated sodium-ion capacitor delivers excellent electrochemical performance by anode/cathode mass matching.

Abstract

2D MXenes are attractive for energy storage applications because of their high electronic conductivity. However, it is still highly challenging for improving the sluggish sodium (Na)-ion transport kinetics within the MXenes interlayers. Herein, a novel nitrogen-doped Ti3C2Tx MXene was synthesized by introducing the in situ polymeric sodium dicyanamide (Na-dca) to tune the complex terminations and then utilized as intercalation-type pseudocapacitive anode of Na-ion capacitors (NICs). The Na-dca can intercalate into the interlayers of Ti3C2Tx nanosheets and simultaneously form sodium tricyanomelaminate (Na3TCM) by the catalyst-free trimerization. The as-prepared Ti3C2Tx/Na3TCM exhibits a high N-doping of 5.6 at.% in the form of strong Ti–N bonding and stabilized triazine ring structure. Consequently, coupling Ti3C2Tx/Na3TCM anode with different mass of activated carbon cathodes, the asymmetric MXene//carbon NICs are assembled. It is able to deliver high energy density (97.6 Wh kg−1), high power output (16.5 kW kg−1), and excellent cycling stability (≈ 82.6% capacitance retention after 8000 cycles).

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

The efficient and price-advantaged energy storage technologies are all important for high-energy and power storage fields, such as communications, smart grids, and electric vehicles [1, 2]. Sodium (Na)-ion energy storage technologies are the most promising alternatives to lithium (Li)-ion energy storage devices due to the similar physical and chemical properties of Na and Li [3]. Additionally, Na has the advantages of being naturally abundant and widely distributed [4]. In particular, Na-ion capacitors (NICs) are emerging rapidly, which can bring the energy density one-step closer towards bridging the battery–supercapacitor divide [5]. However, Na ions have more sluggish transfer kinetics due to their larger radius compared to Li ions (1.02 vs. 0.76 Å) [6]. This disadvantage poses a significant challenge for researchers to develop the NICs that could achieve high energy–power densities and outstanding cycle stability simultaneously [7, 8]. For example, the conventional graphite used for Li-ion battery exhibits a low Na storage capacity of ≈ 35 mAh g–1, which is far from enough for the practical applications. Hence, it is urgent to controllable synthesis of novel electrode materials, ensuring rapid diffusion and reversible adsorption/desorption of Na ions during the charging/discharging process.

Two-dimensional (2D) MXenes are a series of carbides and carbonitrides with excellent conductivity of up to 10,000 S cm–1, thereby receiving an increasing attention in the fields of energy storage and conversion [9, 10]. Typically, they are synthesized through etching the element “A” (mostly Al or Si element) from the MAX precursor and represented using the general formula Mn+1XnTx, where M is transition metals (such as Ti, V, or Nb), X represents C or N, n = 1, 2, or 3, and Tx stands for –F, –O, and –OH surface functional groups [11,12,13]. Of more than 30 MXenes, Ti3C2Tx was the first one to be discovered [14], which has an obvious layered structure with an initial interlayer spacing of ≈ 9.8 Å. In general, Ti3C2Tx MXene is an ideal intercalation-type pseudocapacitive material owing to the abundant as well as tunable terminations Tx [15], which facilitate faster capacitive response and higher energy storage capacity compared to other carbon-based materials. Theoretical calculations have already proven that the Ti3C2Tx with low –F, but high –O surface groups showed higher pseudocapacitive characteristics. For example, using density functional theory (DFT) computations, Zhou et al. demonstrated that the –F terminations induce high ionic diffusion and electronic transfer barriers, thereby decreasing the Li or Na storage capacity of Ti3C2 immensely [16]. Therefore, engineering high pseudocapacitive heteroatoms (such as N, P, and S) on the surfaces and between the interlayers of Ti3C2Tx seems to be a good strategy [17, 18]. In particular, N has the excellent characteristics of electronegativity and pseudocapacitance [3, 19], which could significantly improve the surface electronic and chemical properties of Ti3C2Tx electrodes. However, the synthetic strategy based on chemically doped MXenes has not been clearly established. In addition, the N-sources with high toxicity and low boiling point, such as urea and ammonia, may cause inconvenience to production and living [20]. Accordingly, the novel and efficient methods are urgently desired to promote the development and application of MXene materials in energy storage and conversion fields.

Achieving efficient bonding of high electrochemically active polymers with 2D Ti3C2Tx MXenes is considered as a promising technology [10, 12]. In particular, the trimerization of small molecules to compounds contained triazine ring structure is commonly known in the chemical process of carbonitrides [21], including the famous trimerization reaction of cyanamide (CH2N2) to melamine (C3H6N6). As early as 1922, the trimerization of dicyanamide anions (C2N3− or N(CN)2−) to tricyanomelaminate ions (C6N93−) through the heating method in solid phase was reported [22]. To the best of our knowledge, no follow-up studies of the C2N3− anionic trimerization were reported in the energy storage field. Sodium dicyanamide (Na-dca) is the commercially available product, which can be applied to fabricate organic superconductors or synthesize heterocyclic compounds [23]. Na-dca could intercalate, covalently engineer, and in situ polymerize to sodium tricyanomelaminate (Na3TCM) between the Ti3C2Tx interlayers, which simultaneously acts as intercalant and N-source. Na-dca as the N-source has low toxicity and light pungent smell compared to urea and melamine [20]. More importantly, the sp2-hybridized triazine rings provide high as well as stable N atoms, which are connected by the strong covalent bonds for ensuring the stability during electrochemical cycles [19]. Thus, we proposed a reliable and controllable strategy for achieving highly N-doped Ti3C2Tx through a highly novel method of the in situ trimerization of cyano groups (C≡N).

In this work, we utilized a one-step strategy toward endowing a modified Ti3C2Tx (Ti3C2Tx/Na3TCM) anode for NICs. The as-obtained Ti3C2Tx/Na3TCM exhibited a large interlayer spacing (12.6 Å) and high N-doping (5.6 at.%). The DFT calculations and kinetic analysis have proved that the doped N atoms reduce the Na adsorption energy and Na-ion diffusion kinetic barriers; and the ultra-fast Na-ion storage kinetics was achieved by the increased pseudocapacitance. As anode for NICs, the Ti3C2Tx/Na3TCM showed a high and reversible capacity of 243.4 mAh g−1 at 20 mAg−1 and an ultra-cycle stable capacity of 182 mAh g−1 after 1000 cycles at 0.1 A g−1. Basing on the charge balance principle, the Ti3C2Tx/Na3TCM anode was well matched with activated carbon (AC) cathode in the different mass ratios (1:1, 1:2, 1:3) for achieving better charge-transfer kinetics. The NICs with the anode/cathode mass ratio of 1:2 (Ti3C2Tx/Na3TCM//AC-1:2) delivered high energy and power densities (97.6 Wh kg−1 at 76 W kg−1 and 36.6 Wh kg−1 at 16.5 kW kg−1) as well as ultra-stable cycling life within 0–4.0 V (≈ 82.6% capacitance retention after 8000 cycles).

2 Experimental

2.1 Synthesis of Ti3C2Tx MXene

Ti3C2Tx was synthesized by treating 2 g of Ti3AlC2 (11 Technology Co., Ltd.) in 40 mL of 40% HF aqueous solution for 24 h at 30 °C and 200 rpm. The resulting solution was centrifuged at 4000 rpm to remove the impurities and residual HF until the pH reached 6–7. Finally, the obtained powders were dried in vacuum at 60 °C for 24 h.

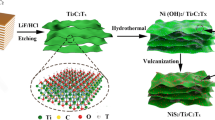

2.2 Synthesis of Ti3C2Tx/Na3TCM Composite

Ti3C2Tx/Na3TCM composite was prepared by a simple hydrothermal for the thermal trimerization of sodium dicyanamide (Na-dca) to sodium tricyanomelaminate (Na3TCM) between Ti3C2Tx interlayers. In a typical synthesis, 200 mg of Na-dca (Aladdin, 98%) was dissolved in 40 mL of deionized water. After that, 200 mg of Ti3C2Tx was dispersed in the as-obtained Na-dca solution and stirred at room temperature at 400 rpm for 2 h. Then, the mixture was sealed in the N2 atmosphere and sonicated in an ice bath at 250 W for 1 h to produce a homogeneous solution. Subsequently, the mixed solution was transferred to a Teflon-lined autoclave and the temperature was raised to 180 °C at a heating speed of 2 °C and then maintained for 6 h. The resulting powder was washed several times with deionized water during vacuum filtration and then dried at 60 °C in the vacuum oven.

2.3 Materials Characterization

FT-IR spectra were recorded with a Thermo Fisher 6700 spectrometer by using the KBr pellet method. XRD patterns were obtained with a Rigaku D/Max 2400 diffractometer by using Cu Kα radiation operated at 45 kV and 200 mA. Nitrogen sorption/desorption isotherms were characterized at 77 K with a Micromeritics ASAP 2020 analyzer. Prior to the gas adsorption, powders were outgassed at 120 °C for 8 h under a vacuum of 10−6 Torr. To further characterize the structure, the as-prepared samples were observed and characterized using the SEM (Hitachi, SU8220) and HR-TEM (FEI, Eindhoven, The Netherlands). In addition, XPS measurements were measured using an ESCALAB 250 analyzer with an Al Kα X-ray source and a base pressure of 1 × 10−9 mbar.

2.4 Electrochemical Measurement

The working electrodes (Ti3C2Tx and Ti3C2Tx/Na3TCM anode, AC cathode) were prepared by mixing the active material (80 wt%), polyvinylidene fluoride (10 wt%), and acetylene black (10 wt%) in N-methyl-2-pyrrolidone (NMP) solvent. The obtained mixtures were coated on the Cu foil for anode or Al foil for cathode and then dried at 80 °C in vacuum oven for 12 h. The loading and diameter of working electrode were 1.6–1.8 mg cm–2 and 11 mm, respectively. The electrolyte was 1 M NaClO4 in ethylene carbonate, diethyl carbonate (EC/DEC, v/v = 1:1) with 5 vol% fluoroethylene carbonate (FEC) as the electrolyte additive, and the glass microfiber GF/D was used as separator. For half-cell, the working electrodes were assembled with metallic Na in a CR2032 coin-type cell. For NICs, the Ti3C2Tx/Na3TCM anode was discharged and charged for 10 cycles in a half-cell at 0.1 A g−1 and then assembled with the YP80F AC cathode in the mass ratios of 1:1, 1:2, 1:3 in the CR2032 coin-type cell. All cells were assembled and disassembled inside a glove box with sub 0.1 ppm water and oxygen contents. The electrochemical performances were evaluated using the Land CT2001A testers system and Biologic VMP3 electrochemical workstation. The EIS was performed at the frequency range from 100 kHz to 0.01 Hz. The energy density E (Wh kg−1) and power density P (W kg−1) were calculated using Eqs. 1 and 2 [24, 25]:

where I (A g−1) is the specific discharge current based on the total mass of active material on both electrodes, V (V) is the discharge voltage, and t (s) is the discharge time.

2.5 Calculating Details

The DFT calculations were carried out using the projector-augmented wave pseudopotentials as implemented in the Vienna ab initio simulation package (VASP) [26]. Exchange correlation interactions were described by the Perdew–Burke–Ernzerhof generalized gradient approximation (GGA) [27]. Since the dipole and van der Waals (vdW) effects on total energy were small, no dipole and vdW corrections were considered. The plane wave kinetic energy cutoff was set to be 500 eV. Atomic positions and lattice parameters were fully relaxed at the GGA level until the atomic forces were smaller than 0.01 eV Å−1. The convergence criteria for structural optimization was set to be 10−5 eV in energy. The Na-ion diffusion barriers on the Ti3C2Tx surface were calculated using the climbing image nudged elastic band (CI-NEB) method [28]. A 1 × 1 × 1 unit cell was used to evaluate the adsorption properties of O and F atoms on Ti3C2 surface. A 3 × 3 × 1 supercell was used to investigate the diffusion barrier of Na ion. The Brillouin zone was represented by Monkhorst–Pack special k-point mesh of 12 × 12 × 1 for the unit cell and 4 × 4 × 1 for supercell calculations, respectively. The adsorption energy (Eads) of the atoms and adsorbates was calculated according to the following equation: Eads = Etotal – Eadsorbates – Ea, where Etotal, Eadsorbates, and Ea are the total energies of the relaxed adsorption system, the various adsorbates, and the adsorbed atom (O, F, or Na), respectively.

3 Results and Discussion

3.1 Structure Characterization

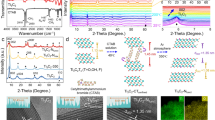

The synthetic scheme of Ti3C2Tx/Na3TCM nanosheets is illustrated in Fig. 1a; the accordion-like Ti3C2Tx was produced by selective etching of the Al element from precursor Ti3AlC2 [29, 30]. The obtained Ti3C2Tx was dispersed in the Na-dca solution and followed with stirring and ultrasonic processes under N2 atmosphere. Afterward, the C2N3− ions trimerize to form C6N93− ions during the hydrothermal process, resulting in stable and high N-doping effect. Meanwhile, the C6N93− ions were covalently engineered between the Ti3C2Tx interlayers by breaking sectional Ti–F bonds and the electrostatic interactions during solvent evaporation [28]. The successful trimerization of C2N3− ions (Fig. 1b, inset) was confirmed based on the Fourier-transform infrared (FT-IR) spectra. The vibration peaks at 2180 and 2286 cm–1 decrease sharply due to the formation of C6N93− ions as shown in the red spectrum in Fig. 1b. In an opposite manner, two strong peaks at about 1398 and 1516 cm–1 appear, indicating the vibration of triazine/benzene structures [31, 32]. The peaks at 1635 and 1670 cm−1 could be attributed to the C–O and C=O bonds, respectively, and the small peak at 1320 cm−1 corresponds to the stretching vibration of C–N bond [33]. It is noteworthy that the C6N93− consists of a triazine ring with three N≡C–N. The ring has no threefold symmetry because of the turning of one of the N≡C–N sidearms, preventing the further long-chain polymerization [21]. Furthermore, interestingly, C2N3− ions were trimerized without catalysts during the entire work, which may be attributed to the functional groups or the interstratified pressure of Ti3C2Tx. This advantage contributes to the cost saving and the environmental protection.

a Schematic illustration of the synthesis for the Ti3C2Tx/Na3TCM. b FTIR spectra of Na-dca, Ti3C2Tx, and Ti3C2Tx/Na3TCM; inset shows the thermal trimerization process of C2N3− to C6N93−. Peak labels correspond to (black circle) 2231 cm–1 vsC–N + vasC–N, (black diamond) 2286 cm–1 vsC≡N and 2180 cm–1 vasC≡N, (black club suit) 1398 and 1516 cm–1 vasRing N + vsRing N. c XRD patterns of Ti3C2Tx and Ti3C2Tx/Na3TCM; inset shows the magnification of XRD patterns. Peak labels correspond to (black circle) amorphous carbon and (black triangle)Ti3C2Tx

To further investigate the interlayer spacing and the crystalline phase of Ti3C2Tx/Na3TCM, the X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns were carried out (Fig. 1c). A broad peak centered at around 23° can be observed in Ti3C2Tx/Na3TCM, which is assigned to the scattering of amorphous carbon derived from trimerization products [31, 32, 34, 35]. Besides, no supererogatory diffraction peaks are found after introducing Na3TCM, confirming the successful synthesis of Ti3C2Tx/Na3TCM composite. The Ti3C2Tx could survive throughout the hydrothermal reactions without appearing damage in morphology and texture mainly due to the protection of nanoplating of Na3TCM [36]. Interestingly, the (002) peak moves toward a lower diffraction angle from 8.8° in Ti3C2Tx to 6.8° in Ti3C2Tx/Na3TCM, and the average interlayer spacing can be calculated by the center position of (002) peaks using the Bragg formula [37]. Ti3C2Tx/Na3TCM has a larger average interlayer spacing of 12.6 Å compared to Ti3C2Tx of 10.0 Å, allowing for additional intercalation and adsorption of Na ions. In addition, we used theoretical calculations combined with experimental result to illustrate the existence of dca− and TCM3− ions between the Ti3C2Tx/Na3TCM MXene interlayers. The schematic drawing about the size of dca− and TCM3− ions and the widths of single Ti3C2 layer are presented in Fig. S1, which are obtained by the DFT calculation. Since the interlayer spacing of Ti3C2Tx/Na3TCM is 1.26 nm and the thickness of single Ti3C2 layer is 0.47 nm, a slant manner of intercalated dca− and TCM3− ions to the broad plane is considered. Hence, the expansion of interlayer spacing is attributed to the combined effects of polymerized C6N93− ions and dissociated Na+ ions [38], thereby providing an open spacing and avoiding the stacking and stability issues of 2D nanosheets.

X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) analysis was implemented to illustrate the interaction between intercalated atoms and Ti3C2Tx matrix (Fig. S2a). The Ti 2p XPS spectrum of Ti3C2Tx is complicated to define due to the various Ti oxidation states. Nevertheless, we can easily observe that the Ti 2p deconvolution peak breaks up into two sublevels by spin–orbit coupling, and the peak centered at 456.4 eV is fitted and assigned to Ti–N (Fig. 2a) [39]. Interestingly, the peak areas and positions of various Ti oxidation states are slightly changed due to the effective combination of Ti and C6N93− ions. The content of N atom increases from 0.0 to 5.6 at.% due to the trimerization of C2N3− (Table S1). N 1s XPS spectrum of Ti3C2Tx/Na3TCM can be fitted with three components for pyrrolic N (21.7%), pyridinic N (55.6%), and N–Ti (22.7%) at the binding energies of 400.6, 399.2, and 396.3 eV, respectively (Fig. 2b) [40]. The nearly 80% of pyrrolic N and pyridinic N derived from triazine rings could rapidly store Na ions and provide high pseudocapacitance [3, 32]. This result proves that C6N93− is synthesized, meanwhile covalently bonded with the Ti atom. To further confirm the interior covalent interactions of N and Ti atoms, the depth profiling of XPS was displayed by using the Ar-ion sputtering method (Fig. S3) [41]. After 62 and 124 s of sputtering, the position and shape of N 1s and Ti 2p spectra were not changed, further confirming the strong covalent bonds between N and Ti atoms. On the other hand, the –F termination on MXene surface could benefit the formation of stable SEI layer [42]. However, vast –F terminations induce high ionic diffusion barrier, while not participate in any pseudocapacitive energy storage processes [16, 43]. Hence, the MXenes with more –O terminal groups and fewer –F terminal groups can be expected as electrodes. In Ti3C2Tx/Na3TCM, the intensity of the Ti–F peaks decreased quickly and the contents of N increased significantly in XPS analysis (Figs. S2b and 2b), indicating that large amount of –F terminal groups was replaced by C6N93− ions. It is because that the Ti–F bond is easily broken during hydrothermal process, and the electronegativity of N and F is similar. In addition, the C 1s XPS spectra were investigated to clarify the structure of the composite (Fig. S2c). Notably, a redshifting of about 0.3 eV could be observed for the C–Ti bonding in Ti3C2Tx/Na3TCM due to the changed Ti atomic environment. The N=C–N in triazine rings in Ti3C2Tx/Na3TCM confirmed the formation of Na3TCM, and the C–Ti–N at 287.1 eV further proved the covalent interactions of N and Ti atoms. Importantly, the Na 1s peak centered at ≈ 1071 eV indicates the pre-intercalated Na ions, which is similar to that of alkalized MXenes (Fig. S2d) [8, 44]. These Na ions play the role of pillar effect and make up for the irreversible capture of Na ions during electrochemical cycling, which will be discussed below.

Characterization of Ti3C2Tx/Na3TCM and Ti3C2Tx. a High-resolution Ti 2p XPS spectra of Ti3C2Tx/Na3TCM (top) and Ti3C2Tx (bottom). b High-resolution N 1s XPS spectra of Ti3C2Tx/Na3TCM (top) and Ti3C2Tx (bottom); insets in bottom show the schematic illustration of N functional groups. c Pore size distributions of Ti3C2Tx/Na3TCM and Ti3C2Tx; inset shows the nitrogen adsorption–desorption isotherms. d Top-view SEM image of Ti3C2Tx/Na3TCM. HR-TEM images of e Ti3C2Tx and f Ti3C2Tx/Na3TCM. g STEM image of Ti3C2Tx/Na3TCM and the corresponding elemental mapping images of h C, i Ti, j O, k N and l Na

To provide another evidence of pillar effect, the pore structure and specific surface area analysis were carried out. Observed from the nitrogen adsorption–desorption isotherms, Ti3C2Tx/Na3TCM exhibits the type IV isotherm with a hysteresis loop at the relative pressure from 0.5 to 1.0, indicating the coexistence of micropores and mesopores (Fig. 2c) [45]. Ti3C2Tx/Na3TCM has a large average pore size of ≈ 4 nm, which indicates that C6N93− ions were obtained between the Ti3C2Tx interlayers. Such “generous” pore structure is essential to achieve high-rate pseudocapacitive energy storage in the 2D nanosheets by accelerating rapid Na-ion diffusion kinetics [46]. Also, Ti3C2Tx/Na3TCM possesses a Brunauer–Emmett–Teller specific surface area of 183.4 m2 g−1, which is nearly 6 times higher than that of the pristine Ti3C2Tx (32.5 m2 g−1). The increased surface area comes from the contribution of highly N-doped trimerization products, which might increase the electrolyte-accessible areas and active sites.

As shown in Figs. 2d and S4, obviously, Ti3C2Tx/Na3TCM exhibits a well-preserved 2D nanosheet structure similar to that of pristine Ti3C2Tx. Discriminatively, the trimerization products on the Ti3C2Tx surfaces provide abundant active surface, which is well matched with the pore structure analysis. Combining the high-resolution TEM (HR-TEM) images with corresponding patterns [47], the average interlayer spacing of the 2D nanosheet increases from 10.1 Å of Ti3C2Tx to 12.6 Å of Ti3C2Tx/Na3TCM (Figs. 2e, f and S5), agreeing well with the XRD results. The STEM image and corresponding elemental maps illustrate the spatial distribution of C, Ti, O, N, and Na elements of Ti3C2Tx/Na3TCM at the nanometer scale (Fig. 2g–l). It can be clearly seen that N (orange color) has the same distribution as the even distributed Ti and O elements, demonstrating that C6N93− ions are anchored and/or fastened on the Ti3C2Tx matrix. However, Na (green color) displays a wide range covering on the Ti3C2Tx matrix like the C element. It can be hypothesized that besides the preformation of –ONa, = NNa on the Ti3C2Tx surface, abundant Na ions exist in the secondary piled structure of 2D Ti3C2Tx, which could also be considered as the pre-intercalated Na ions. These pre-intercalated Na ions make up for the irreversible and captured Na ions derived from the electrolyte, which might be combined with defects and heteroatoms during the desodiation process, thereby assisting the improvement in Na storage capacity and cycle stability [44, 48]. Furthermore, a series of complicated Moiré patterns are displayed in the HR-TEM image of Ti3C2Tx/Na3TCM (Fig. S6) [49], indicating the multilayered heterostructure of polymerized C6N93− stacking on the Ti3C2Tx matrix.

3.2 Electrochemical Performance Tests in Half-Cell

The Na-ion storage performance was investigated by using the coin-type half-cells in the potential window of 0.01–3.0 V (vs. Na/Na+). According to the first three cyclic voltammetry (CV) curves of Ti3C2Tx and Ti3C2Tx/Na3TCM, the cathodic peaks at the range of 0.2–1.75 V of the first CV curve show the formation of SEI film or the decomposition of electrolyte (Fig. S7a, b) [50]. And the nearly overlapped second and third CV curves prove the good cycle stability. Interestingly, a symmetric anodic/cathodic peak shown at ≈0.09 V of Ti3C2Tx/Na3TCM indicates the reversible desodiation and sodiation process, respectively. The cyclic stability is therefore improved, because the pre-intercalated Na ions supplement the Na ions derived from the electrolyte, which are irreversible combined with the defects and heteroatoms during the desodiation process. However, for the Ti3C2Tx, no anodic peaks are exhibited to correspond to the sharp cathodic peak. The current responses in CV tests were recorded at scan rates from 0.1 to 1.0 mV s−1 (Figs. 3a and S7c). The shape of the CV curves for the two electrodes is well preserved as the increasing scan rates, indicating good rate capability and small electrode polarization. The Ti3C2Tx/Na3TCM shows two redox couples approximately at 1.21/1.12 and 2.72/2.38 V, which are assigned to the following additional reactions [49, 51]: (1) pseudocapacitive (de)adsorption of Na ions on the N-rich surface; (2) (de)intercalation of Na ions into the nanovoids.

Electrochemical performance and kinetic analysis of Ti3C2Tx/Na3TCM and Ti3C2Tx for Na-ion storage. a CV curves of Ti3C2Tx/Na3TCM at different scan rates from 0.1 to 1 mV s−1. b Charge–discharge curves of the 1st cycle and the 20th cycle at the current density of 20 mA g−1. c Rate performance at various current densities from 20 mA g−1 to 5000 mA g−1. d Long-term cycling performance and the coulombic efficiency at the current density of 100 mA g−1. e Nyquist plots of Ti3C2Tx − 1, Ti3C2Tx − 50, Ti3C2Tx − 200 and Ti3C2Tx/Na3TCM − 1, Ti3C2Tx/Na3TCM − 50, Ti3C2Tx/Na3TCM − 200. f The determination of the b values at cathodic and anodic peaks regimes of the Ti3C2Tx/Na3TCM (top) and the Ti3C2Tx (bottom). g The b values of anodic peaks at the different potentials. h Capacitive contribution ratios at various scan rates from 0.1 to 1 mV s−1

Observed from the galvanostatic charge/discharge (GC/D) curves at the current density of 20 mA g−1 (Fig. 3b), Ti3C2Tx/Na3TCM and Ti3C2Tx exhibit initial discharge/charge capacities of 746.8/247.7 and 493.1/185.6 mAh g−1, resulting in the low coulombic efficiency of ≈ 35% for the first cycle. Such low coulombic efficiency at initial charge/discharge cycle could be also obtained in the previously reported 2D MXene materials, such as Ti2CTx [52] and V2CTx [53]. The irreversible capacity loss is most likely caused by the formation of SEI film or the decomposition of electrolyte, which is consistent with the results obtained by CV tests. However, after a few initial cycles, the reversible discharge capacities (the 20th cycle) of 243.4 and 148.2 mAh g−1 were exhibited in Ti3C2Tx/Na3TCM and Ti3C2Tx, respectively. In addition, Ti3C2Tx/Na3TCM has superior high-rate capacities of 210, 174, 157, 147, 135, 109, and 95 at 50, 100, 200, 500, 1000, 2000, and 5000 mA g−1, respectively (Fig. 3c). The excellent electrochemical performance is attributed to the enlarged interlayer spacing, open porosity, and N-doping. To further investigate the cycling stability, the two electrodes were evaluated at 100 mA g−1 for long cycling (Fig. 3d). It is impressive that the Ti3C2Tx/Na3TCM retains a reversible capacity of 182.2 mAh g−1 (≈ 112% of the initial value) after 1000 cycles, which is superior to the Ti3C2Tx of only 97.6 mAh g−1 after 1000 cycles. The specific capacity of Ti3C2Tx decreases sharply during the first 40 cycles, which is caused by the irreversible capture of Na ions by the defects. In comparison, Ti3C2Tx/Na3TCM exhibits a sustaining and growing capacity, which entirely comes from the contribution of pre-intercalated Na ions. This result further demonstrates that the symmetric anodic/cathodic peaks appear in the CV curve of Ti3C2Tx/Na3TCM rather than Ti3C2Tx, and the mapping relation of C and Na atoms is also confirmed. Further, the coulombic efficiency of the two electrodes gradually stabilizes at ≈ 99% after the first few cycles. Undeniably, the difference in electrochemical performances is directly related to the microstructure and composition, which become the conclusive factors for charge storage. We have proved that the trimers coated and Na-ion pre-intercalated Ti3C2Tx could markedly facilitate the Na-ion storage.

Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) was utilized to reveal the charge transfer characteristics. Nyquist plots consist of a semicircle at high to middle frequencies region and an inclined line at low frequency, which is associated with the ionic diffusion (Fig. 3e) [54]. Basing on the equivalent circuit model (Fig. S8), these points were fitted using the solid lines in the same color (Table S2). For the Ti3C2Tx/Na3TCM, the value of Rct corresponds to the semicircle and increases from 6.25 (after 1 cycle) to 21.81 (after 50 cycles) and then to 172.1 Ω (after 200 cycles), which may be caused by the deterioration on the surface of materials during cycling [55]. However, the value of Rct of Ti3C2Tx increases from 170.4 (after 1 cycle) to 223.5 (after 50 cycles) and then to 365.9 Ω (after 200 cycles), indicating that the Ti3C2Tx/Na3TCM has superior structure for ions transport and electrons transfer. The reasons come from the contribution of the increased N-rich sites and the enlarged interlayer spacing.

To qualitatively evaluate the capacitive contribution, we analyzed the kinetics behaviors of Na-ion storage according to the mathematical equation of \(i=a{v}^{b}\). Here, v is the scan rate, a is a constant, and b is an adjustable parameter that ranges from 0.5 (diffusion-controlled process) to 1 (surface-controlled or capacitive process) [56]. The b value is much closer to 1, suggesting the larger capacitive contribution to total capacity storage. When b is closer to 0.5, diffusion control dominates. High proportion of capacitive contribution facilitates the fast Na-ion storage and promote ultra-high-rate performance [3, 8]. The b values of the oxidation and reduction peaks in the Ti3C2Tx/Na3TCM are closer to 1 than that in the Ti3C2Tx (Fig. 3f), suggesting the ultra-fast Na-ion storage kinetics of Ti3C2Tx/Na3TCM governed by the capacitive process. Even the potentials are far from the anodic peak potentials; the b values of Ti3C2Tx/Na3TCM and Ti3C2Tx both fluctuate within the range of 0.5–1 (Fig. 3g). This finding suggests that the total capacity storage is the combination of capacitive and diffusion-controlled processes. According to the power-law relationship, the specific capacity can be quantificationally divided into the capacitive (k1v) effects and diffusion-controlled behavior (k2v1/2) as follows [57]: \(i\left(V\right)={k}_{1}v+{k}_{2}{v}^{1/2}\) (Figs. S9 and S10). The capacitive contribution gradually raises with the increasing scan rates (Fig. 3h), and the maximal capacitive contribution ratio of 91.2% vs. 83.1% (Ti3C2Tx/Na3TCM vs. Ti3C2Tx) could be obtained at the scan rate of 1.0 mV s−1. In general, the capacitive capacity is provided by the electrical double-layer capacitive (EDLC) one and the pseudocapacitive one. The EDLC materials generally have a high specific surface area up to 2000 m2 g−1 due to the proportional relationship of specific capacitance and specific surface area [56]. As is well known, multilayer Ti3C2Tx MXene is the representative pseudocapacitive electrode with a low specific surface area of only ≈50 m2 g−1. Thus, the capacitance-controlled capacities of Ti3C2Tx/Na3TCM and Ti3C2Tx electrodes are basically from the pseudocapacitive contribution. This finding strongly reveals that the electrolyte could be easily accessible to the enlarged interlayer spacing and modified surface of Ti3C2Tx/Na3TCM, promoting the ultra-fast Na-ion storage kinetics.

3.3 First-Principles Calculations

The first-principles calculations were performed to present a clear understanding for the remarkable Na storage capacity of N-rich Ti3C2Tx surface. First, it is obvious that the O atom (Fig. 4a–c) and F atom (Fig. S11) both prefer to occupy the face-centered cubic (fcc) site to form the Ti3C2O and Ti3C2F structures (Table S3). The O and F atomic adsorption energies on the 1 × 1 Ti3C2 surface occupied at fcc site are − 9.74 and − 7.20 eV, respectively. Then, a 3 × 3 Ti3C2OF structure was constructed to focus on the adsorption of Na as shown in Fig. S12. After the calculations of all possible Na-adsorbed sites on the Ti3C2OF surface, the most stable Na-adsorbed fcc site was obtained (Fig. 4d). According to the results obtained from XPS, the increased N ratio is approximate to the decreased F ratio on the Ti3C2Tx surface. Therefore, a Ti3C2Tx/Na3TCM model in the form of the substitute of a N atom to a F atom was established; subsequently, the most stable Na-adsorbed site on this surface was obtained (Fig. 4e). The calculation results show that a Na atom on the most stable site of N-doped Ti3C2Tx (− 3.22 eV) has the lower Eads than that of pristine Ti3C2Tx (− 3.05 eV). This finding easily indicates that the increased N atom reduces the adsorption energy of total system, thereby promoting the Na-ion storage. Importantly, the electrochemical diffusion barriers could intuitively reflect the Na-ion storage kinetics, which is a great point of exploration. Hence, the nudged elastic band (NEB) method was performed to investigate the diffusion barriers of Na ion on the Ti3C2Tx surface with or without N-doping. Beforehand, the most stable structures were set as the final sites and the same diffusion paths were controlled (Fig. S13). The obtained result shows that ≈ 0.03 eV energy barrier reduces after introducing a N atom at the expense of a F atom (Fig. 4f). The calculation results prove that the Na-ionic diffusion rate increases after N-doping; subsequently, the N-doped Ti3C2Tx surface absorbs Na-ion easier, thereby boosting the additional intercalation of free Na ions from the electrolyte, which is in good agreement with the experimental results.

DFT calculations for the Na-ion storage on the Ti3C2Tx/Na3TCM and Ti3C2Tx surface. Top view of an O atom adsorbed on 1 × 1 Ti3C2 surface at a top site, b bcc site and c fcc site. Top view of a Na adsorbs on the most stable site on 3 × 3 surface of d Ti3C2Tx and e Ti3C2Tx/Na3TCM. f Diffusion profiles of the Na on Ti3C2Tx and Ti3C2Tx/Na3TCM surface in the NEB calculations

3.4 Electrochemical Performance Tests in NICs

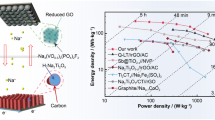

Basing on the excellent Na-ion storage performance, Ti3C2Tx/Na3TCM was used as anode coupled with the YP80F AC cathode to assemble NICs (Ti3C2Tx/Na3TCM//AC) in the 1 M NaClO4 electrolyte. The pore structure characteristics of the AC and the electrochemical performance of AC//Na half-cell within 1.5–4.0 V (vs. Na+/Na) are displayed in Figs. S14 and S15, respectively. Figure 5a illustrates the charge storage mechanism of the Ti3C2Tx/Na3TCM//AC NICs. During the charge process, ClO4− ions are trapped at the defects and absorbed on the O-contained surface of AC cathode. For the anode, Na+ ions are intercalated into the interlayers and absorbed on the N-rich surface of Ti3C2Tx/Na3TCM. Similarly, the discharge process is reversible but reverse. Anode/cathode dynamic matching is the key to optimize performance of hybrid ion capacitors, and the electrode mass ratio is thus optimized to balance the capacities and achieve targeted voltage swings [58]. Basing on the charge balance principle [59], the asymmetric NICs coupling the Ti3C2Tx/Na3TCM anode with AC cathode in the mass ratio of 1:1, 1:2, and 1:3 were constructed. The voltage window of the NICs was set from 0 to 4 V (vs. Na+/Na) to maximize the working voltage (Fig. S16). Figure 5b compares the typical CV curves of the above different NIC at a scan rate of 20 mV s−1. Apparently, the shapes of these CV curves are diverged from the ideal rectangular shape, indicating the combined contribution of the Faradaic and non-Faradaic reactions. Further, Fig. S17 shows the CV and GC/D curves of the three Ti3C2Tx/Na3TCM//AC NICs at the different rates, which also demonstrate the multiple energy storage mechanisms. It can be easily observed that the Ti3C2Tx/Na3TCM//AC NIC-1:2 has the highest energy storage performance obtained by comparing the integral areas. The energy–power densities of the devices were quantificationally obtained based on the total mass of the active materials of both anode and cathode (Fig. 5c). The Ti3C2Tx/Na3TCM//AC NIC-1:2 shows excellent energy–power densities of 97.6 Wh kg−1 at 76 W kg−1 and remains 36.6 Wh kg−1 even at 16.5 kW kg−1, and the maximal power density is higher than the recommended target for commercial electric vehicles (15 kW kg−1). It is worth to note that the Ti3C2Tx/Na3TCM//AC NIC-1:2 could finish charge/discharge process within 36 s, and a high energy density of 50 Wh kg−1 is still achieved. It is sure that the superior energy–power characteristics of Ti3C2Tx/Na3TCM//AC NIC-1:2 is attributed to the reasonable charge matching, which reduces the ion transport resistance and generates a stable solid–electrolyte interface [58, 59]. In contrast, the energy density of Ti3C2Tx/Na3TCM//AC NIC-1:3 drops sharply as the power density increases, indicating the difference in charge-transfer kinetics at the high-power outputs.

a Charge storage mechanism of the Ti3C2Tx/Na3TCM//AC NICs. b CV curves of Ti3C2Tx/Na3TCM//AC NICs based on various anode/cathode ratios (1:1, 1:2, 1:3) at a scan rate of 20 mV s−1. c Ragone plots of the Ti3C2Tx/Na3TCM//AC NICs compared with the advanced MXene-based LICs and NICs. d Capacitance retention and coulombic efficiency of the Ti3C2Tx/Na3TCM//AC tested at 4.0 A g−1

It is instructive to compare the energy–power characteristics of the device to the state-of-the-art reported asymmetric MXene//carbon configurations in the literature. Hence, the Ragone plot of the Ti3C2Tx/Na3TCM//AC NICs was performed in comparison with the advanced MXene-based NICs and LICs, such as Na-Ti3C2//AC (NIC) [8], bistacked-Ti3C2//YP17 AC (NIC) [29], Ti2C//AC (LIC) [60], Ti3C2@CNT//AC (LIC) [61], CTAB@Sn@Ti3C2//AC (LIC) [62], TiC//N-doped porous carbon (LIC) [63], and Nb2CTx-CNT//Nb2CTx-CNT (LIC) [64]. Indeed, the field of asymmetric MXene//carbon capacitors is almost new and contains few examples of complete devices. As could be seen from Fig. 5c, although the Ti3C2Tx/Na3TCM//AC NIC-1:2 not achieves the highest value of energy density compared with the previously reported devices, it is undeniable that this device belongs to one of the best examples with the integrated considerations of energy and power characteristics. Furthermore, the cycling performance of all obtained devices was evaluated at the current density of 4.0 A g−1 (Fig. 5d). The Ti3C2Tx/Na3TCM//AC NIC-1:2 exhibits a preeminent capacitance retention of ≈ 90.8% after 4000 cycles and ≈ 82.6% after 8000 cycles. The coulombic efficiency in the range of 97–99% is shown during the steady-state cycling, which is on par with that reported hybrid devices [8, 65]. The low coulombic efficiency shown in the other mass matching may be due to the mismatching of anode and cathode kinetics. In brief, the advanced electrochemical performances of Ti3C2Tx/Na3TCM//AC NIC-1:2 device result from the following noteworthy reasons: (1) The pre-intercalated Na ions pillar the Ti3C2Tx interlayer and supply for the irreversible Na ions trapped in the nanovoids; (2) the enlarged surface area and average pore size provide abundant active surface; (3) the in situ formed N atoms significantly increase the pseudocapacitive response; and (4) the reasonable dynamic matching balances the charge of anode and cathode.

4 Conclusions

In summary, we have demonstrated a novel and reliable strategy for synthesizing highly N-doped 2D Ti3C2Tx nanosheets and performed their superior Na-ion storage performance. Benefiting from the enlarged interlayer spacing and N-rich surface, the designed Ti3C2Tx/Na3TCM exhibited fast and high Na-ion storage capability that was verified through joint results of experiments and DFT calculations. With an asymmetric Ti3C2Tx MXene//activated carbon configuration, the 4.0 V Ti3C2Tx/Na3TCM//AC-1:2 NIC device has been successfully assembled, delivering high energy density of 97.6 Wh kg−1, high power density of 16.5 kW kg−1, and outstanding cycle stability of 82.6% capacitance retention after 8000 cycles. The chemistry of N-doping Ti3C2Tx by in situ trimerization strategy employed in this work is available for further studying the competitive polymer molecules/MXenes hybrid electrodes with high electrochemical activity.

References

M. Armand, J.-M. Tarascon, Building better batteries. Nature 451, 652–657 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1038/451652a

J. Sun, H.-W. Lee, M. Pasta, H. Yuan, G. Zheng, Y. Sun, Y. Li, Y. Cui, A phosphorene–graphene hybrid material as a high-capacity anode for sodium-ion batteries. Nat. Nanotechnol. 10, 980–U184 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1038/NNANO.2015.194

W. Shao, F. Hu, C. Song, J. Wang, C. Liu, Z. Weng, X. Jian, Hierarchical N/S co-doped carbon anodes fabricated through a facile ionothermal polymerization for high-performance sodium ion batteries. J. Mater. Chem. A 7, 6363–6373 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1039/c8ta11921j

Z.-L. Xu, S. Yao, J. Cui, L. Zhou, J.-K. Kim, Atomic scale, amorphous FeOx/carbon nanofiber anodes for Li-ion and Na-ion batteries. Energy Storage Mater. 8, 10–19 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ensm.2017.03.010

J. Ding, H. Wang, Z. Li, K. Cui, D. Karpuzov, X. Tan, A. Kohandehghan, D. Mitlin, Peanut shell hybrid sodium ion capacitor with extreme energy-power rivals lithium ion capacitors. Energy Environ. Sci. 8, 941–955 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1039/c4ee02986k

J. Yang, X. Zhou, D. Wu, X. Zhao, Z. Zhou, S-doped N-rich carbon nanosheets with expanded interlayer distance as anode materials for sodium-ion batteries. Adv. Mater. 29, 1604108 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.201604108

J. Ding, W. Hu, E. Paek, D. Mitlin, Review of hybrid ion capacitors: from aqueous to lithium to sodium. Chem. Rev. 118, 6457–6498 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.chemrev.8b00116

J. Luo, C. Fang, C. Jin, H. Yuan, O. Sheng et al., Tunable pseudocapacitance storage of MXene by cation pillaring for high performance sodium ion capacitors. J. Mater. Chem. A 6, 7794–7806 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1039/c8ta02068j

C. Zhang, L. McKeon, M.P. Kremer, S.-H. Park, O. Ronan et al., Additive-free MXene inks and direct printing of micro-supercapacitors. Nat. Commun. 10, 1795 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-09398-1

M. Boota, B. Anasori, C. Voigt, M.-Q. Zhao, M.W. Barsoum, Y. Gogotsi, Pseudocapacitive electrodes produced by oxidant-free polymerization of pyrrole between the layers of 2D titanium carbide (MXene). Adv. Mater. 28, 1517–1522 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.201504705

M. Naguib, V.N. Mochalin, M.W. Barsoum, Y. Gogotsi, 25th anniversary article: MXenes—a new family of two-dimensional materials. Adv. Mater. 26, 992–1005 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.201304138

Z. Ling, C.E. Ren, M.-Q. Zhao, J. Yang, J.M. Giammarco, J. Qiu, M.W. Barsoum, Y. Gogotsi, Flexible and conductive MXene films and nanocomposites with high capacitance. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 111, 16676–16681 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1414215111

M. Alhabeb, K. Maleski, B. Anasori, P. Lelyukh, L. Clark, S. Sin, Y. Gogotsi, Guidelines for synthesis and processing of two-dimensional titanium carbide (Ti3C2Tx MXene). Chem. Mater. 29, 7633–7644 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.chemmater.7b02847

B. Anasori, M.R. Lukatskaya, Y. Gogotsi, 2D metal carbides and nitrides (MXenes) for energy storage. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2, 16098 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/natrevmats.2016.98

P. Srimuk, F. Kaasik, B. Kruner, A. Tolosa, S. Fleischmann et al., MXene as a novel intercalation-type pseudocapacitive cathode and anode for capacitive deionization. J. Mater. Chem. A 4, 18265–18271 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1039/c6ta07833h

Q. Tang, Z. Zhou, P. Shen, Are MXenes promising anode materials for Li ion batteries? Computational studies on electronic properties and Li storage capability of Ti3C2 and Ti3C2X2 (X = F, OH) monolayer. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 16909–16916 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1021/ja308463r

M. Lu, H. Li, W. Han, J. Chen, W. Shi et al., 2D titanium carbide (MXene) electrodes with lower-F surface for high-performance lithium–ion batteries. J. Energy Chem. 31, 148–153 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jechem.2018.05.017

Y. Tang, J. Zhu, W. Wu, C. Yang, W. Lv, F. Wang, Synthesis of nitrogen-doped two-dimensional Ti3C2 with enhanced electrochemical performance. J. Electrochem. Soc. 164, A923–A929 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1149/2.0041706jes

F. Hu, T. Zhang, J. Wang, C. Liu, S. Li, S. Hu, X. Jian, Simple fabrication of high-efficiency N, O, F, P-containing electrodes through host–guest doping for high-performance supercapacitors. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 6, 15764–15772 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1021/acssuschemeng.8b04331

Y. Yoon, M. Lee, S.K. Kim, G. Bae, W. Song et al., A strategy for synthesis of carbon nitride induced chemically doped 2D MXene for high-performance supercapacitor electrodes. Adv. Energy Mater. 8, 1703173 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1002/aenm.201703173

B. Jürgens, E. Irran, J. Schneider, W. Schnick, Trimerization of NaC2N3 to Na3C6N9 in the solid: Ab initio crystal structure determination of two polymorphs of NaC2N3 and of Na3C6N9 from X-ray powder diffractometry. Inorg. Chem. 39, 665–670 (2000). https://doi.org/10.1021/ic991044f

A.P. Purdy, E. Houser, C.F. George, Lithium dicyanamide, its reactions with cyanuric chloride, and the crystal structures of LiN(CN)2(MeCN)2 and LiCN(C5H5N)2. Polyhedron 16, 3671–3679 (1997). https://doi.org/10.1016/S0277-5387(97)00097-1

S.R. Batten, P. Jensen, B. Moubaraki, K.S. Murray, R. Robson, Structure and molecular magnetism of the rutile-related compounds M(dca)2, M = CoII, NiII, CuII, dca = dicyanamide, N(CN)2–. Chem. Commun. (1998). https://doi.org/10.1039/a707264c

D. Xu, D. Chao, H. Wang, Y. Gong, R. Wang, B. He, X. Hu, H.J. Fan, Flexible quasi-solid-state sodium-ion capacitors developed using 2D metal–organic-framework array as reactor. Adv. Energy Mater. 8, 1702769 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1002/aenm.201702769

Z. Mao, R. Wang, B. He, Y. Gong, H. Wang, Large-area, uniform, aligned arrays of Na3(VO)2(PO4)2F on carbon nanofiber for quasi-solid-state sodium-ion hybrid capacitors. Small 15, 1902466 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1002/smll.201902466

G. Kresse, J. Furthmüller, Efficient iterative schemes for ab initio total-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set. Phys. Rev. B 54, 11169–11186 (1996). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.54.11169

J.P. Perdew, K. Burke, M. Ernzerhof, Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865–3868 (1996). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.77.3865

G. Henkelman, B.P. Uberuaga, H. Jonsson, A climbing image nudged elastic band method for finding saddle points and minimum energy paths. J. Chem. Phys. 113, 9901–9904 (2000). https://doi.org/10.1063/1.1329672

N. Kurra, M. Alhabeb, K. Maleski, C.-H. Wang, H.N. Alshareef, Y. Gogotsi, Bistacked titanium carbide (MXene) anodes for hybrid sodium ion capacitors. ACS Energy Lett. 3, 2094–2100 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1021/acsenergylett.8b01062

M.-Q. Zhao, X. Xie, C.E. Ren, T. Makaryan, B. Anasori, G. Wang, Y. Gogotsi, Hollow MXene spheres and 3D macroporous MXene frameworks for Na-ion storage. Adv. Mater. 29, 1702410 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.201702410

L. Hao, J. Ning, B. Luo, B. Wang, Y. Zhang et al., Structural evolution of 2D microporous covalent triazine-based framework toward the study of high-performance supercapacitors. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 137, 219–225 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1021/ja508693y

F. Hu, J. Wang, S. Hu, L. Li, W. Shao et al., Engineered fabrication of hierarchical frameworks with tuned pore structure and N, O-co-doping for high-performance supercapacitors. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 9, 31940–31949 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1021/acsami.7b09801

S. Huang, Z. Li, B. Wang, J. Zhang, Z. Peng, R. Qi, J. Wang, Y. Zhao, N-doping and defective nanographitic domain coupled hard carbon nanoshells for high performance lithium/sodium storage. Adv. Funct. Mater. 28, 1706294 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1002/adfm.201706294

D.-G. Wang, H. Wang, Y. Lin, G. Yu, M. Song, W. Zhong, G.C. Kuang, Synthesis and morphology evolution of ultrahigh content nitrogen-doped, micropore-dominated carbon materials as high-performance supercapacitors. Chemsuschem 11, 3932–3940 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1002/cssc.201801892

X. Huang, J. Tang, B. Luo, R. Knibbe, T. Lin et al., Sandwich-like ultrathin TiS2 nanosheets confined within N, S codoped porous carbon as an effective polysulfide promoter in lithium-sulfur batteries. Adv. Energy Mater. 9, 1901872 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1002/aenm.201901872

X. Wu, Z. Wang, M. Yu, L. Xiu, J. Qiu, Stabilizing the MXenes by carbon nanoplating for developing hierarchical nanohybrids with efficient lithium storage and hydrogen evolution capability. Adv. Mater. 29, 1607017 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.201607017

G. Du, M. Tao, W. Gao, Y. Zhang, R. Zhan, S. Bao, M. Xu, Preparation of MoS2/Ti3C2Tx composite as anode material with enhanced sodium/lithium storage performance. Inorg. Chem. Front. 6, 117–125 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1039/c8qi01081a

J. Luo, X. Tao, J. Zhang, Y. Xia, H. Huang et al., Sn4+ ion decorated highly conductive Ti3C2 MXene: promising lithium-ion anodes with enhanced volumetric capacity and cyclic performance. ACS Nano 10, 2491–2499 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1021/acsnano.5b07333

W. Bao, L. Liu, C. Wang, S. Choi, D. Wang, G. Wang, Facile synthesis of crumpled nitrogen-doped MXene nanosheets as a new sulfur host for lithium–sulfur batteries. Adv. Energy Mater. 8, 1702485 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1002/aenm.201702485

C. Yang, Y. Tang, Y. Tian, Y. Luo, M.F.U. Din, X. Yin, W. Que, Flexible nitrogen-doped 2D titanium carbides (MXene) films constructed by an ex situ solvothermal method with extraordinary volumetric capacitance. Adv. Energy Mater. 8, 1802087 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1002/aenm.201802087

J. Luo, J. Zheng, J. Nai, C. Jin, H. Yuan et al., Atomic sulfur covalently engineered interlayers of Ti3C2 MXene for ultra-fast sodium-ion storage by enhanced pseudocapacitance. Adv. Funct. Mater. 29, 1808107 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1002/adfm.201808107

X. Guo, W. Zhang, J. Zhang, D. Zhou, X. Tang et al., Boosting sodium storage in two-dimensional phosphorene/Ti3C2Tx MXene nanoarchitectures with stable fluorinated interphase. ACS Nano 14, 3651–3659 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1002/aenm.201702485

X. Chen, Y. Zhu, M. Zhang, J. Sui, W. Peng et al., N-Butyllithium-treated Ti3C2Tx MXene with excellent pseudocapacitor performance. ACS Nano 13, 9449–9456 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1021/acsnano.9b04301

S. Sun, Z. Xie, Y. Yan, S. Wu, Hybrid energy storage mechanisms for sulfur-decorated Ti3C2 MXene anode material for high-rate and long-life sodium-ion batteries. Chem. Eng. J. 366, 460–467 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2019.01.185

N. Sun, Q. Zhu, B. Anasori, P. Zhang, H. Liu, Y. Gogotsi, B. Xu, MXene-bonded flexible hard carbon film as anode for stable Na/K-ion storage. Adv. Funct. Mater. 29, 1906282 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1002/adfm.201906282

G. Jiang, N. Zheng, X. Chen, G. Ding, Y. Li, F. Sun, Y. Li, In-situ decoration of MOF-derived carbon on nitrogen-doped ultrathin MXene nanosheets to multifunctionalize separators for stable Li-S batteries. Chem. Eng. J. 373, 1309–1318 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2019.05.119

B. Yang, J. Chen, S. Lei, R. Guo, H. Li, S. Shi, X. Yan, Spontaneous growth of 3D framework carbon from sodium citrate for high energy- and power-density and long-life sodium-ion hybrid capacitors. Adv. Energy Mater. 8, 1702409 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1002/aenm.201702409

X. Jin, H. Huang, A. Wu, S. Gao, M. Lei, J. Zhao, X. Gao, G. Cao, Inverse capacity growth and pocket effect in SnS2 semi-filled carbon nanotube anode. ACS Nano 12, 8037–8047 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1002/aenm.201702485

Y.-P. Zhu, Y. Lei, F. Ming, E. Abou-Hamad, A.-H. Emwas, M.N. Hedhili, H.N. Alshareef, Heterostructured MXene and g-C3N4 for high-rate lithium intercalation. Nano Energy 65, 104030 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nanoen.2019.104030

S. Li, J. Qiu, C. Lai, M. Ling, H. Zhao, S. Zhang, Surface capacitive contributions: towards high rate anode materials for sodium ion batteries. Nano Energy 12, 224–230 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nanoen.2014.12.032

Y. Ma, Q. Guo, M. Yang, Y. Wang, T. Chen et al., Highly doped graphene with multi-dopants for high-capacity and ultrastable sodium-ion batteries. Energy Storage Mater. 13, 134–141 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ensm.2018.01.005

X. Wang, S. Kajiyama, H. Linuma, E. Hosono, S. Oro, I. Moriguchi, M. Okubo, A. Yamada, Pseudocapacitance of MXene nanosheets for high-power sodium-ion hybrid capacitors. Nat. Commun. 6, 6544 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms7544

S.-M. Bak, R. Qiao, W. Yang, S. Lee, X. Yu et al., Na-ion intercalation and charge storage mechanism in 2D vanadium carbide. Adv. Energy Mater. 7, 1700959 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1002/aenm.201700959

J. Dahn, G.M. Ehrlich, T. Reddy, in Linden’s Handbook of Batteries, ed. by T. B. Reddy, 4th ed., (McGraw-Hill, New York, 2011).

X. Guo, X. Xie, S. Choi, Y. Zhao, H. Liu, C. Wang, S. Chang, G. Wang, Sb2O3/MXene(Ti3C2Tx) hybrid anode materials with enhanced performance for sodium-ion batteries. J. Mater. Chem. A 5, 12445–12452 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1039/c7ta02689g

T. Brezesinski, J. Wang, S.H. Tolbert, B. Dunn, Ordered mesoporous α-MoO3 with iso-oriented nanocrystalline walls for thin-film pseudocapacitors. Nat. Mater. 9, 146–151 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1038/NMAT2612

F. Yu, Z. Liu, R. Zhou, D. Tan, H. Wang, F. Wang, Pseudocapacitance contribution in boron-doped graphite sheets for anion storage enables high-performance sodium-ion capacitors. Mater. Horiz. 5, 529–535 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1039/c8mh00156a

H. Wang, D. Mitlin, J. Ding, Z. Li, K. Cui, Excellent energy-power characteristics from a hybrid sodium ion capacitor based on identical carbon nanosheets in both electrodes. J Mater. Chem. A 4, 5149–5158 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1039/c6ta01392a

H. Wang, C. Zhu, D. Chao, Q. Yan, H.J. Fan, Nonaqueous hybrid lithium-ion and sodium-ion capacitors. Adv. Mater. 29, 1702093 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.201702093

J. Come, M. Naguib, P. Rozier, M.W. Barsoum, Y. Gogotsi, P.-L. Taberna, M. Morcrette, P. Simon, A non-aqueous asymmetric cell with a Ti2C-based two-dimensional negative electrode. J. Electrochem. Soc. 159, A1368–A1373 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1149/2.003208jes

P. Yu, G. Cao, S. Yi, X. Zhang, C. Li, X. Sun, K. Wang, Y. Ma, Binder-free 2D titanium carbide (MXene)/carbon nanotube composites for high-performance lithium-ion capacitors. Nanoscale 10, 5906–5913 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1039/c8nr00380g

J. Luo, W. Zhang, H. Yuan, C. Jin, L. Zhang et al., Pillared structure design of MXene with ultralarge interlayer spacing for high-performance lithium-ion capacitors. ACS Nano 11, 2459–2469 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1021/acsnano.6b07668

H. Wang, Y. Zhang, H. Ang, Y. Zhang, H.T. Tan et al., A high-energy lithium-ion capacitor by integration of a 3D interconnected titanium carbide nanoparticle chain anode with a pyridine-derived porous nitrogen-doped carbon cathode. Adv. Funct. Mater. 26, 3082–3093 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1002/adfm.201505240

A. Byeon, A.M. Glushenkov, B. Anasori, P. Urbankowski, J. Li et al., Lithium-ion capacitors with 2D Nb2CTx (MXene)-carbon nanotube electrodes. J. Power Sources 326, 686–694 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpowsour.2016.03.066

Z. Xu, M. Wu, Z. Chen, C. Chen, J. Yang, T. Feng, E. Paek, D. Mitlin, Direct structure-performance comparison of all-carbon potassium and sodium ion capacitors. Adv. Sci. 6, 1802272 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1002/advs.201802272

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the support from the National Key Research and Development Program (No. 2018YFB1107500), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 51503024), the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (Nos. DUT17RC(3)003, DUT18RC(4)033), and the National Natural Science Foundation of the Joint Fund Key Projects (No. U1663226).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, S., Hu, F., Shao, W. et al. A Novel Strategy of In Situ Trimerization of Cyano Groups Between the Ti3C2Tx (MXene) Interlayers for High-Energy and High-Power Sodium-Ion Capacitors. Nano-Micro Lett. 12, 135 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40820-020-00473-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40820-020-00473-7