Abstract

New species of the subfamily Myrmicinae are described from the fossil volcanogenic Lake Enspel, Westerwald, Germany. This Fossil-Lagerstätte comprises lake sediments, which essentially consist of intercalated “oilshales” and volcaniclastics. The sediments were dated to be of late Oligocene age. Out of the 287 fossil ants from Enspel examined, 96.5% (n = 277) belong to the formicoid clade (Formicinae, Dolichoderinae, Myrmicinae), and only 3.5% (n = 10) to the poneroid clade (Ponerinae, Agroecomyrmecinae). The high proportion of Myrmicinae (36.6%) indicates that this subfamily was already strongly represented in Central Europe in the late Oligocene. However, it should be noted that the large number of specimens are alate reproductives. The number of workers is low: n = 19, or 6.1% of 312 specimens when 25 isolated wings are included. Ten new species, belonging to the genera Paraphaenogaster, Aphaenogaster, Goniomma and Myrmica are named. Taxonomic questions regarding the separation of the two genera Aphaenogaster and Paraphaenogaster as well as aspects of biogeography, palaeoenvironment and palaeobiology in Enspel are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Regarding their biodiversity and ecological position, the success story of ants has been elaborated by Hölldobler and Wilson (1990, 2010) and since then repeatedly mentioned by many other authors (e.g. Dlussky and Wedmann 2012; LaPolla et al. 2013). According to AntCat (Bolton 2019), there are 13,575 extant valid species described.

The study of the evolutionary history of ants is a challenge. The reconstruction of the evolutionary steps from the very beginning of ant evolution up to the status we have today can only be solved by a combination of taxonomic, genetic and palaeontological research (Ward 2007; LaPolla et al. 2013; Barden 2017).

The earliest fossil records of ants are from the Upper Cretaceous of France (99-100 Ma) and Burmese amber (99 Ma) (LaPolla et al. 2013; Barden 2017). Recently, one ant fossil has been documented from the Paleocene of Alberta (Canada) (La Polla and Barden 2018). The Eocene is comparatively well represented by 12 fossil sites: In Baltic amber, Bitterfeld (Germany), Denmark, Rovno (Ukraine), Sakhalin (Russia), Cambay (India), Oise (France) and Fushun (China), or in former lacustrine sediments from the Okanagan Highlands (Canada/USA), Green River (USA), Messel (Germany), Bembridge (UK), Florissant (USA, shale) and in marine sediments of the Isle of Fur (Denmark). In contrast, only six fossil sites are known from the Oligocene: Fonseca Formation (Brazil), Aix-en-Provence, Cereste (both France), Kleinkems, Enspel and Rott (all Germany). Ants from Miocene have been reported from numerous fossil sites, i.e. Stavropol (Russia), Radoboj (Croatia), Shanwang (China), Öhningen (Germany), Dominican Republic and Crete (Greece). With regard to the fossils found in Sicilian amber (Italy), no exact geological age is known; the data range from Eocene to Miocene (Ragazzi and Roghi 2014). The former Paleocene ants from Sakhalin amber (Russia) and Isle of Fur (Denmark) have been redated as Eocene (Kodrul 1999; Larsen et al. 2003), whereas the Fur Formation represents the transition from Paleocene to Eocene. Fossil Pliocene ants are known from Willershausen (Germany) (Dlussky et al. 2011).

Hypotheses on myrmicine evolution vary. In the “Dynastic Succession Hypothesis” by Wilson and Hölldobler (2005), tropical forest soils and ground litter in the angiosperm forest are interpreted as the “headquarters” of ant evolution. While living in soil litter, they supported nitrogen production, which had a beneficial effect on the growth of angiosperms (Berendse and Scheffer 2009). The authors assume that the Myrmicinae living in these habitats radiated in the early Eocene and surpassed the Ponerinae in biodiversity and biomass. In addition, Myrmicinae were able to add seeds and elaiosomes to their diet and were able to expand into dry habitats such as grasslands and deserts later on.

The “African Origin Hypothesis” (Dlussky et al. 2004; Radchenko and Dlussky 2013) is primarily based on the early fossil record (genus Afromyrma) from Late Cretaceous mudstones in Botswana (Africa). According to this hypothesis, the subfamily Myrmicinae evolved in Africa. When they invaded Europe (possibly via the Tethys Sea by rafting), an adaptive radiation led to a relative high number of genera (25). At that time, myrmicine ants were very likely arboreal dwellers or at least foraging on trees, because the number of workers found in amber is relatively high, compared to the number of workers belonging to real epigaeic living taxa. Although the proportion of myrmicine specimens in European Eocene amber is low (Dlussky and Rasnitsyn 2009), Radchenko and Dlussky (2013) stress the increase of new myrmicine genera in late Eocene amber as possibly being the cause of the decrease of poneroid taxa in amber, compared to their high number found in mid-Eocene Messel deposits (Dlussky and Wedmann 2012). As most of the Eocene myrmicine genera are extinct, the authors suppose that they could not compete with other myrmicine taxa or with taxa from other subfamilies invading Europe.

The “New World Tropic Hypothesis” by Ward et al. (2015) is based on DNA-sequencing and sequence annotation. In their study, the subfamily Myrmicinae is consistently recovered as monophyletic, with the exception of the ant genus Ankylomyrma Bolton 1973. The authors reduced the number of tribes from 25 down to 6 crown groups of Myrmicinae. Their results indicate that the diversification of crown-group Myrmicinae began about 100 Ma ago and was initially concentrated in the New World tropics. These tribes range in age from 52.3 to 71.1 Ma. Their divergence dating estimates show that the early and mid-Eocene (55–40 Ma) was an important period of diversification for myrmicine ants. The earliest fossil records on Myrmicinae are from early-middle Eocene and they show a considerable taxonomic diversity (Perkovsky 1915; Dlussky and Rasnitsyn 2002; Radchenko and Perkovsky 2016). The fossil record supports the authors’ inference that the major lineages of Myrmicinae had already originated by this time.

The main difference between the first two hypotheses is the early habitat of Myrmicinae. Radchenko and Dlussky (2013) interpret early Myrmicinae as arboreal dwellers, whereas Wilson and Hölldobler (2005) assume the forest soil and ground litter as the early habitat of the myrmicine ants. The study of Ward et al. (2015) does not support the African Origin Hypothesis either. The African genus Afromyrma (Dlussky et al. 2004), however, was not used as an a priori calibration in their dating analysis, because it is not accepted by other myrmicologists (Wilson and Hölldobler 2005; Archibald et al. 2006).

According to Wilson and Hölldobler (2005) and Ward et al. (2015), myrmicine ant diversification took place in early to mid-Eocene. This, however, is not reflected in the fossil record. The number of myrmicine specimens from all Eocene and Oligocene deposits in Eurasia and North America do not make more than 5–6% (Radchenko and Dlussky 2013). The proportion of myrmicine specimens from European amber is only 2.1–13.2%, while the proportion of myrmicine genera is relatively high at 38% (Dlussky and Rasnitsyn 2009; Radchenko and Dlussky 2013). Only during the Late Oligocene to mid Miocene do the number of myrmicine ants specimens increase to contemporary percentages, i.e. Kleinkems 36% (early Oligocene), Enspel 36.6% (Upper Oligocene MP 28, this paper), Rott 50% (late Oligocene, MP 30), Radoboj 22% (early Miocene) and Vishnevaya balka, Stavropol 40% (mid Miocene) (Dlussky and Wedmann 2012). These findings, however, are in accordance with earlier statements by Ward (2000), according to whom the numbers of fossil myrmicine ant specimens became similar to the modern ones (about 74%) by the mid Miocene.

The volcanogenic Lake Enspel is an oil shale deposit with abundant and diverse fossil insects. According to Wedmann (2000), there is a predominance of Coleoptera (53%), followed by Diptera (24%) and Hymenoptera (12%). Six percent of the fossils belong to Trichoptera, mainly represented as larvae (n = 4222). Among the Hymenoptera, ants make about 50%.

Wedmann et al. (2010) give a preliminary study on ant fossils from Enspel. In this study, subfamilies were identified but not quantified. A high proportion of Myrmicinae was found, mainly belonging to the morphogenus Paraphaenogaster (personal communication G. Dlussky, cited in Wedmann et al. 2010).

The essential goal of the paper is to describe the myrmicine fauna of Lake Enspel. Additionally, the fossil ants of Lake Enspel are allocated down to the subfamily level, and their different percentages are stated. The other subfamilies will be described elsewhere. As geological and palaeobotanical data on Enspel are published, palaeoenvironmental aspects can be discussed.

Material und methods

All fossils are currently stored in the Directorate General for Cultural Heritage Rhineland-Palatinate, Directorate Archaeo-logy, Department Earth History, Mainz, Germany. In the long term, they will be deposited in the “Typothek” of the State Collection of Natural History Rhineland-Palatinate/Museum of Natural History Mainz, Mainz, Germany (NHMM).

Fossil ants were found during yearly excavation campaigns between 1995 and 2013 conducted by the Directorate General for Cultural Heritage Rhineland-Palatinate, Directorate Archaeology, Department of Earth History.

In Enspel, the quality of preservation of ants is often exceptional, as shown by chitin preserved in its primary organic molecular structure (Stankievics et al. 1997; Colleary et al. 2015) and by original colours of insects (McNamara 2013). The amount of melanin in the chitin determines the darkness of an insect. For the fossil deposit Messel (Germany), it has been shown that melanin is preserved (Vinther 2015). Since it is not systematically demonstrated for Enspel, colour cannot be considered as a taxonomic characteristic. Deviations in the preservation of structural colours from sample to sample within the same fossil location were documented by McNamara et al. (2012).

Abbreviation of specimen numbers: NHMM = Naturhistorisches Museum Mainz; PE = Palaeontology Entomology; 2009 = found in 2009; 6281 = running inventory number of the year; LS = Landessammlung (State Collection). Information on the layer is given. They refer to the standard profile in Felder et al. (1998).

Photographs were taken with a photomicroscope Leica M205C DFC500. Enlarged prints were hand traced by pen, and drawings were scanned and redone/improved by standard graphical software (Photoshop, Inkscape). Details were elaborated by examination with a Binocular M7 Wild Heerbrugg.

Full lines indicate sclerite boundaries, dashed lines indicate supposed sclerite boundaries or supposed veins, short strokes with rounded corners indicate visible sclerite margins. Preserved sclerites are coloured grey, preserved wings are coloured slightly less grey.

Remark

It is important to always keep both plates (A and B) of the insect body fossil while excavating. When sedimentary rocks are split, parts of the fossil insect can be found on each plate. As an example: propodeal spines or the number of antenna segments are of high taxonomic value. Unfortunately, these fragile body parts break off easily and might be left on the opposite plate.

Terminology

Morphological terminology follows Bolton (1994), and in its expansion the Morphological Terms in Antwiki. According to Antwiki, the term “node” is …A rounded or knob-like structure, commonly used to refer to the dorsal nodes of the petiole or postpetiole. The term “peduncle” is used for a more or less slender anterior section of the petiole, which begins immediately posterior to the propodeal-petiolar articulation and extends back to the petiolar node. It is very variable in length and thickness, but when present in any form, the petiole is termed pedunculate.

Nomenclature of the wing venation follows Dlussky and Perfilieva (2014) and Perfilieva et al. (2017) (Fig. 1).

The sculpture of the sclerites often is well preserved, as are sometimes fragile parts, like bristles and tibial spurs. Normally in papers dealing with fossil ants, the terms “imprint fossil” or “impression fossil” are used. For ants from Enspel, these terms are not appropriate. It has been shown by Stankiewicz et al. (1997) that the original chitin molecular structure has been preserved in insect body fossils from Enspel. In addition, for fossil weevils from Enspel Gupta et al. (2007) showed that the aliphatic polymer in the insect fossils did not derive from migration from the organic-rich host sediment. Therefore, the terms insect body fossil or compression fossil are more appropriate and will be used in this paper.

Posteriorly to the pars stridens of the stridulation organ, there are integumentary foldings on the presclerite of the first gastral tergite. These foldings are preserved in some specimens described here. They are most likely functionally linked to the stridulation organ. When the gaster moves back and forth, the male produces a sound. Studies on extant species show that the sound differs between the species (Castro et al. 2015). Àlvarez (2009) named these structures “pillars”. The term “pillars” will also be used here, although “furrows and ridges” would often describe their morphology better. Most likely they evolved from the girdling constriction respectively “cinctus3” (see Serna and Mackay 2010).

Measurements

Measurements on compression fossils can only be approximations because of perspective distortion or deformation. Significant deformation mainly happens to softly sclerotized parts; other parts with stronger sclerotization show little or no deformation. To support the validity of the measurements, body parts positions are mentioned. Measurements are taken as seen, deviations from reality due to perspective distortions are considered exceptional. Where a measurement cannot be taken precisely because the start or ending point is not seen, the measurement is noted as being an estimate (est.). The gaster is often incomplete or damaged. In addition, gaster length can vary because of its telescoping variability (Tschinkel 2013). This makes the dimension BL only an approximate value. For this reason, the value BL without gaster (BLw/oG) is given additionally.

Measurements are given in mm. BL: addition of MML, HL, AL, PL, PPL and GL, completed by estimations where needed; BLw/o G: addition of MML, HL, AL, PL and PPL; THL: HL including mandibles; HL: head length, without mandibles; HW: maximum head width excluding eyes; HW* measured from mid ocellum to mid eye x2 (for specimens which are embedded strongly dorsolateral to overcome foreshortening); ED: eye diameter; GeL: Gena length; SL: scape length; ML: mandibles length; MML: length of masticatory margin of mandibles; AL: alitrunk length, measured from head connection to the most posteroventral point of alitrunk; AH: alitrunk height, measured from the ventral margin of mesopleuron to highest point of mesonotum; AW: alitrunk width; ScuL: scutum length; ScutL: scutellum length; MesoL: length of mesonotum (worker); PL: petiole length (ventral dimensions, measured from most anterior ventral point to most posterior ventral point); PH: petiole height; PPL: postpetiole length (ventral dimensions, measured from most anterior ventral point to most posterior ventral point); PPH: postpetiole height; PPW: postpetiole width; HeH: helcium height; HeW: helcium width; G1L: length of first gastral segment, measured from medio-anterior margin of first gastral tergite to medio posterior margin of first gastral tergite; G1W: width of first gastral tergite; GL: gaster length (in most cases estimated, because of incompleteness); FWL: forewing length; 2M+Cu: length of vein 2M+Cu (inner dimensions); 1Cu: length of vein 1Cu (inner dimensions); 1M: length of vein 1M (inner dimensions); m-cu: length of vein m-cu (inner dimensions); 1RS+M: length of vein 1RS+M (inner dimensions); 2RS+M: length of vein 2RS+M (inner dimensions).

Indices: CI = (HW*100)/HL; SI = (SL*100)/HW); IED/HL = (ED*100)/HL; IHL/AL = (HL*100/AL), Imcu = (1RS+M/1Cu)*100; I2RS+M/1RS+M = (2RS+M/1RS+M)*100; I2RS+M/m-cu = (2RS+M/m-cu)*100; I2RS+M/2M+Cu = (2RS+M/2M+Cu)*100.

Geological and palaeoenvironmental background

Lake Enspel, a fossil volcanic crater lake, is part of the Cenozoic Volcanic Field of the High Westerwald Mountains (Germany), marked by the solid line in Fig. 2. This locality represents a late Oligocene deep, limnologically closed lake, which developed in a small volcanotectonic trachytic caldera located about 35 km NE of Koblenz, Germany. The crater was probably formed by an initial phreatomagmatic eruption around 24.79 ± 0.05 Ma ago (Mertz et al. 2007). A closed lake basin developed with an original depth of 240 m, and a diameter of 1.7 × 1.3 km (Pirrung 1998; Pirrung et al. 2001), which existed for up to 200–220 Kyr (Mertz et al. 2007; Herrmann 2010). Afterwards, sedimentation was stopped by a huge basaltic inflow. The sedimentary infill of the crater lake, mainly debrites and turbidites and minor diatomitic black pelites (“oil shale”), is defined as the Enspel Formation (Schäfer et al. 2011). This kind of sedimentation lasted throughout its entire existence (Schindler and Wuttke 2015). The age brackets for the Enspel lacustrine sediments are between 24.56 ± 0.04 and 24.79 ± 0.05 Ma (Mertz et al. 2007). As the fossils were found close to the upper basal flow, their age is close to 24.56 ± 0.04 Ma years.

Tectonic and geographical map of the Westerwald Mountains, showing the location of the Fossil-Lagerstätte Lake Enspel (adapted from Schindler and Wuttke 2010)

A highly diverse flora and fauna is exceptionally well preserved, displayed by primary organic molecules (i.e. chitin) or organelles (Stankievics et al. 1997; Colleary et al. 2015), preservation of primary colours of insects (McNamara 2013) and crop and/or stomach content of, e.g. frogs and birds (Wuttke and Poschmann 2010; Mayr 2013; Smith and Wuttke 2015).

Lake Enspel was surrounded by a relatively high crater rim (Pirrung 1998). During the duration of sedimentation, the rim was episodically eroded, deposited in part temporarily on alluvial fans, and then episodically resedimented on the lake floor. Gullies formed on the subaerial part of the steep inner crater rim, and mudflows occurred in the local gullies (Schindler and Wuttke 2015). The walls and the ground of the gullies were lightly vegetated, displayed by subaerially dessicated owl pellets that were washed episodically into the lake by flowing water (Smith and Wuttke 2015).

The late Oligocene was characterised by pronounced climatic changes that were accompanied by vast vegetational changes. The mean annual temperature of this terrestrial environment was estimated at about 15–17 °C, the warmest month about 25 °C, the coldest one about 5–7 °C and the mean annual precipitation was between 900 and 1355 mm/year (Uhl and Herrmann 2010). Compared to the “World Map of the Köppen-Geiger Climate Classification”, temperature in Enspel was similar to the contemporary Mediterranean, but humidity was significantly higher.

The vegetation was dominated by zonal assemblages of a mesophytic forest with a strong East Asian influence. Based on the fossil macroflora found in Enspel, four communities of plants have been described by Köhler and Uhl (2014): water plants, azonal riparian vegetation (of the lake shore), azonal riparian forest, zonal mesophytic forest/mixed mesophytic forest. The forest consisted of four storeys and reached the lake in non-disturbed parts of the crater rim that was characterised by mostly steep margins. Azonal elements (aquatic and semi-aquatic plants, riparian forest) are only represented based on approximately 15 % of the taphoflora (Köhler and Uhl 2014). Banks of the supposed gullies or streamlets feeding into the lake or shallow marginal areas can also be assumed as the potential growth areas of these plants (Schindler and Wuttke 2015).

Composition of the fossil ant record of Lake Enspel

Between 1995 and 2013, 354 ant fossils were found in Enspel. For 287 of these, the subfamily could be identified (for 42 specimens the subfamily was indeterminable, and in addition there are 25 isolated wings). Myrmicinae make up 36.6% (n = 105) of the specimens, and Formicinae and Dolichoderinae combined 59.9% (n = 172). The distinction of the latter two subfamilies is difficult; 80 fossils could be identified with quite high probability as Formicinae, only 4 as Dolichoderinae, and the remainder were not clearly assignable to either of the two subfamilies. Ponerinae make about 2.1% (n = 6), Agroecomyrmecinae 1.4% (n = 4).

At the present stage, it can be stated that fossil ants from the formicoid clade (Formicinae, Dolichoderinae, Myrmicinae) comprise 96.5% of the total. Specimens belonging to the poneroid clade are represented by 3.5% (n = 10). By far the majority of the specimens are males and alate females, and the number of workers is low: n = 19. This is equivalent to 6.1%, when 25 isolated ant wings are included (n = 312 in total). Fourteen of the 25 isolated wings show the typical “Paraphaenogaster wing venation pattern”.

Systematic palaeontology

Subfamily Myrmicinae Lepeletier de Saint-Fargeau, 1835

Tribus Stenammini Ashmead, 1905

Genus Paraphaenogaster Dlussky, 1981

Type species: Paraphaenogaster microphthalma Dlussky, 1981

The genus Paraphaenogaster originally was described by Dlussky (1981), based on males originating from Miocene sediments in Vishnevaya balka, Stavropol in Russia.

Gyne: BL between 9 and 12 mm. Head usually longer than wide. The occipital corners vary from flattened to well developed. Mandibles sub-triangular to triangular with more than 6 triangular teeth. Apical and sub-apical tooth larger, can be slightly curved. Antenna 12-segmented, no distinct club. High alitrunk with arched mesonotum. Wing venation with closed cells mcu and 1+2r. The vein 5RS reaches far to the distal edge of the forewing, it rarely reaches it completely. So in most species, cell 3r remains open. Cell rm is not developed, because vein rs-m is absent. Sometimes an unsclerotized, thin residue of the vein rs-m can still be detected. Vein 2r-rs short. The distal section of vein M does not branch off from vein RS near the junction 2r-rs/ RS, but much further proximal. Thus, the free distal ends of veins M and RS do not branch off from a common node (see also Radchenko and Perkovsky 2016; Perfilieva et al. 2017). Proximal part of vein M with distinct lumen, towards distal vein turns into a stronger sclerotized line. The distal part seems to be just a stronger sclerotized line, possibly to improve the wings stability, without having any supply function. This also applies for vein 2Cu and 3Cu. Only the proximal part of 2Cu has a distint lumen.

Propodeum armed. Petiole with distinct peduncle, posteriorly ending in a high petiolar node. Petiolar node slightly tapered, rounded. Postpetiole with gradually arising and descending node, not pedunculate. Solid, high helcium articulates higher than mid length at posterior face of petiole. Constriction of postpetiole towards gaster differs, postpetiole can be wider than petiole.

Male: BL 7–12 mm (length of male P. microphthalma was given as 12 mm. The males found in Enspel are between 7 and 10 mm long.) Eye diameter between 0.27 and 0.50 mm. (Eye diameter of 0.27 mm is an estimation for P. microphthalma based on the drawing, the eye diameter of the Enspel males are between 0.35 and 0.50 mm). High and arched mesonotum, moderate descending propodeum. Well-developed sub-triangular mandibles with 4–6 triangular-shaped teeth. For all species described here, the petiole is pedunculate without a high, distinct node. Petiole is slightly ascending towards distal. Postpetiole is mostly elongate with a more or less contricted helcium. Postpetiole can dorsally be dome-shaped. Petiole and postpetiole can be regularly or irregularly striated. Wing venation as gyne.

Worker: BL about 6–8 mm. Head elongate oval, CI around 90. Mandibels triangular with 7–8 teeth. Outer margin of mandible is evenly curved. Alitrunk elongate. In profile, promesonotum can be significantly higher than propodeum, pronotum can be separated from mesonotum by a clear promesonotal suture. Propodeal spines present. Petiole pedunculate, with rounded node.

Differential diagnosis: Paraphaenogaster resembles Aphaeno-gaster to a great extend, i.e. elongate head, 12-segmented antenna, high and arched alitrunk, pedunculate and high-noded petiole. The only criteria to separate Paraphaenogaster from Aphaenogaster are the lack or strong reduction of the cell rm.

Remarks: Since the workers and dealate females lack the fore wings, the main distinguishing feature between the genera Aphaenogaster and Paraphaenogaster is not present. Strictly spoken, it is impossible to allocate worker or dealate females to one or the other genera. This is the weakest point of creating a morphogenus based on the wing venation pattern. However, since the genus Paraphaenogaster is much more represented in Enspel than Aphaenogaster, the worker specimens are assigned to the genus Paraphaenogaster.

Dlussky and Wedmann (2012) stated that it is almost impossible to prove the conspecificity of gynes and males of fossil ants. This is also the case here. There are no specific morphological characteristics that would allow me to state a conspecificity of male and gyne.

Paraphaenogaster loosi sp. nov.

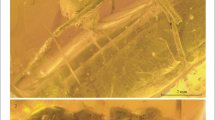

(Fig. 3a, b)

Paraphaenogaster loosi sp. nov., gyne, holotype NHMM-PE1995/5503-LS a+b. a Photomontage, plate a and b combined (photograph of plate a, see Supplementary Data 1: Fig. 1, photograph of plate b, see Supplementary Data 1: Fig. 2). b Line drawing; Paraphaenogaster cf. loosi, gyne, NHMM-PE2013/5037-LS. c Photograph. d Line drawing; Paraphaenogaster cf. loosi gyne, NHMM-PE1995/7896-LS a+b. e Photograph of plate a. f Photomontage of plate a and b combined (see also Supplementary Data 1: Fig. 3; photograph of plate b, see Supplementary Data 1: Fig. 4). g Line drawing

Etymology: Honouring former municiple mayor Gerhard Loos (Westerburg, Germany), in place of all town mayors, local authorities and the county council, who all were engaged to develop the Fossil-Lagerstätte Enspel to the main touristic centrum Stöffel-Park (Enspel, Westerwald Mountains, Germany) by fundraising political and financial support from the state Rhineland-Palatinate and the European Union.

Holotype: NHMM-PE1995/5503-LS a+b, winged gyne.

Position: Head dorsal, alitrunk, petiole, postpetiole, gaster (partly) lateral.

Colour: Brown, both plates a and b existing.

Type locality and horizon: Enspel Oilshale, Rhineland-Palatinate, Germany. Enspel Formation, Upper Oligocene, MP 28; (24.56–24.79 Ma, Mertz et al. 2007), layer S16.

Description: BL about 9.73. Head distinctly longer than wide, with feebly concave sides, smoothly rounded occipital corners. Head length is about 68% of alitrunk length. Anterior margin of clypeus smooth. Eyes slightly longer than wide, located at mid length of head, eye diameter is about 22.3% of head length. Gena well developed. Mandibles sub-triangular, with eight well-developed triangular-shaped teeth; the two first apical teeth larger than the others. Twelve-segmented antenna, no distinct club. Scape just protrudes beyond occipital margin. Surface of the head is sculptured with wide striae. At the occiput striae are also combined with transversal structures, resulting in a reticulate pattern. Alitrunk high, mesonotum arched. Scutum anteriorly covers pronotum. Scutellum thickened and distinctly upraised. It is transverse oval shaped with tapered ends. Propodeal slope steep, propodeum armed with two long spines, directed straight backwards. No propodeal lobes developed. Tibial spurs combed at fore leg, simple at hind leg; for the mid leg it is not clear. Pronotum, propleuren striated, propodeum with transversal strong striae, other parts of alitrunk unspecificly rugose. Mesopleuron large. Posteroventral margin of metasternum almost forms a right angle. Wing venation as in genus description. Apical part of vein 5RS is not preserved, so it is uncertain if cell 3r is closed here. Petiole with long peduncle and distinct node. Peduncle anteroventral with small protrusion. Petiole dorsally with distinct sutures, along peduncles midline and marking the transition from peduncle to node. Node with steep ascending anterior face and steep descending posterior face, dorsally structured rugose. Postpetiole with rounded node. Helcium articulates with petiole at about mid length of posterior face of petiole. Gaster is damaged. However, two continuous break lines prove that the first gastral tergite is the longest one, which is typical for myrmicine ants. Sculpture on first gastral tergite is unspecific rugose, not shiny.

Measurements: Holotype NHMM-PE1995/5503-LS a+b; BLw/oG: 6.87, HL: 1.98, HW: 1.58 (est.), ED: 0.44, GeL: 0.59, ML: 0.96, MML: 0.59 SL: 1.56, AL: 2.91, FWL: 7.69 (est.), ScuL: 1.52, ScutL: 0.62, HiTL: 2.02, PL: 0.90, PH: 0.71, PPL: 0.5, PPH: 0.69, HeH: 0.43, G1L: 1.68 (est.), G1H: 1.53. Wing venation: 2M+Cu: 0.75, 1Cu: 0.71, 1M: 0.38, m-cu: 0.47, 1RS+M: 0.38, 2RS+M: 0.49. Indices: CI: 79.98, SI: 98.85, IED/HL: 22.32, IHL/AL: 67.98, Imcu: 54.17, I2RS+M/1RS+M: 126.92, I2RS+M/m-cu: 95.62, I2RS+M/2M+Cu: 64.71.

Differential diagnosis: P. loosi is characterised by its combination of BL > 9 mm, an arched promesonotum with a protruding scutellum, straight and well-developed propodeal spines, a high, steeply ascending petiolar node, and a nodular postpetiole. As an essential difference to P. tertiaria, this species has a convexly curved clypeus margin and does not show any median indentation (see Dlussky and Putyatina 2014). The clypeus of P. tertiaria is not convexly curved but horizontal in itself, and has a median depression at the anterior clypeus margin.

Paraphaenogaster cf. loosi

(Fig. 3c, d)

Specimen: NHMM-PE2013/5037-LS, winged gyne

Position: Head dorsal, alitrunk, petiole, postpetiole (partly), first gastral tergite dorsolateral.Colour: Black.

Type locality and horizon: Enspel Oilshale, Rhineland-Palatinate, Germany. Enspel Formation, Upper Oligocene, MP 28; (24.56–24.79 Ma, Mertz et al. 2007), layer S14.

Description: BL about 9.03. Head oval, slightly longer than wide, at the sides feebly convex. Smoothly rounded occipital corners, posterior margin median slightly concave, with a distinct small groove. Head length is about 66% of alitrunk length. All dorsal parts of head, including gena, are completely sculptured with distinct widely spaced striae. Towards posterior part of head striation turns to be also combined with transversal structures so it turns to a kind of reticulate pattern. Anterior margin of clypeus convex, median part of clypeus with distinct longitudinal striae. Frontal carinae reaching back to about anterior margin of eyes. Frontal lobes hardly developed. Frons fairly wide. Mandibles sub-triangular. Masticatory margin with about 7 triangular-shaped teeth, all about same size. The apical tooth seems to be slightly bigger but it is not claw-like curved. Eyes located slightly below midlength of head. Eye diameter is about 21.6% of head length. Antenna 12-segmented, no distinct club. Funiculus is not filiform or slender. The top of the apical funicular segment is separated by an additional suture. This apical top is not valued as a separate funicular segment, but is seen as a taphonomic feature, see also chapter: Taphonomic aspects. First funicular segment longer than second, third and forth; the second funicular segment is slightly longer than wide. Scape overtrudes slightly occipital margin of head. Scape is widely curved at base, at bend distinctly narrower than at its distal part. Scutum, scutellum and pronotum with longitudinal rugae, propodeum transversely striated. Scutellum is protruding. Posterior margin of metanotum not distinctly thickened. Propodeal spines unclear, but according to imprint of sediment seen on the photograph, short propodeal spines are very likely. Propodeum with transversal striation at posterior declivity. These are continuing vertical at lateral parts of propodeum. Petiole equipped with long peduncle. Node most likely has been tilted forward and appears flattened due to the caudal-dorsolateral perspective. Postpetiole not preserved but imprints in the sediment indicate the existence of a medium size node. Wing venation with closed cells mcu, 1+2r, open 3r. Shape of cell mcu sub-trapezoid. 1RS comparably long, distinctly inclining distal. Wing venation pattern follows in all other aspects the description of the genus. First gastral tergite large, with homogenous, slightly rugose sculpturing, it is not shining.

Measurements: NHMM-PE2013/5037-LS; BLw/oG: 6.18, HL: 1.82, HW: 1.73, ED: 0.41, GeL: 0.44, ML: 0.91, MML: 0.41, SL: 1.58, AL: 2.76, FWL: 8.23, ScuL: 1.07, ScutL: 0.46, HiTL: 1.79, PL: 0.75, PPL: 0.43 (est.), HeW: 0.32, G1L: 1.93. Wing venation: 2M+Cu: 0.65, 1Cu: 0.65, 1M: 0.28, m-cu: 0.50, 1RS+M: 0.46, 2RS+M: 0.38. Indices: CI: 94.98, SI: 91.58, IED/HL: 22.65, IHL/AL: 65.95, Imcu: 70.45, I2RS+M/1RS+M: 83.87, I2RS+ M/m-cu: 88.26, I2RS+M/2M+Cu: 59.09.

Remarks: This specimen has not been classified as the paratype of P. loosi sp. nov., because the morphology of its petiole and postpetiole is not clear. It differs from P. loosi in its colour. As mentioned above, the colour has no taxonomic value, see Chapter: Material and Methods.

Paraphaenogaster cf. loosi

(Fig. 3e–g)

Specimen: NHMM-PE1995/7896-LS a+b, winged gyne.

Position: Head from ventral, alitrunk from ventrolateral, petiole, postpetiole, and gaster from lateral.

Colour: Black.

Type locality and horizon: Enspel Oilshale, Rhineland-Palatinate, Germany. Enspel Formation, Upper Oligocene, MP 28; (24.56–24.79 Ma, Mertz et al. 2007), layer S12.

Description: BL about 11.89 (see also remark). Head distinctly longer than wide, with smoothly rounded posterior corners. Head length is about 62.3% of alitrunk length. Side parts where eyes are located seem to be slightly concave. Gena convex. Eyes located slightly below mid length of head, eye diameter is about 18.7% of head length. Elongate, sub-triangular mandibles with 6–7 triangular-shaped teeth. First apical tooth bigger than second apical tooth, second apical tooth slightly bigger than the other teeth. Apical tooth is bended. Antenna most likely 12-segmented. Scape protrudes beyond the occipital margin of the head. Alitrunk elongate, relatively flat. Scutum anteriorly covers pronotum; Propleuren irregular longitudinally sculptured. Dorsolateral and lateral parts of propodeum densely striated. Propodeum dorsally with transversal bulgy striae. Propodeal lobes weakly developed, not as distinct as specimen in NHMM PE2010/5496-LS. Length of propodeal spines 0.4 mm, slightly curved downwards. Spine’s base fairly wide. Tibial spurs distinct and combed at fore leg, not clear at middle and hind leg. Wing venation with closed cells mcu and 1+2r. Shape of cell mcu trapezoid. Apical part of vein 5RS does not reach apical margin of forewing. So cell 3r is open. In other respects, the description of the wing venation of the genus applies. Petiole with peduncle and distinct tapered node. In profile, the anterior face of the petiole shows a concave line, the transition from peduncle to node appears slightly smoother here than in P. loosi. Node’s sculpture rugose. Postpetiole with smoothly arising and descending node. Postpetioles node less high than petioles node (according to marks in the sediment), top rounded. Solid and high helcium articulates at mid length at posterior face of petiole. First gastral segment clearly longer than the others and stronger sclerotized, but wihout any specific sculpture. In this specimen, sculpture and sutures are comparatively poorly preserved.

Measurements: NHMM-PE1995/7896-LS a+b; BLw/oG: 7.43, HL: 2.05, HW: 1.82, ED: 0.38, GeL: 0.62, ML: 1.09, MML: 0.71, SL: 1.87 (est.), AL: 3.28, HiTL: 2.05, FWL: 9.0, PL: 0.93, PH: 0.85, PPL: 0.47, PPH: 0.69 (est.), HeH: 0.43. Wing venation: 1Cu: 0.87, 1M: 0.53, m-cu: 0.56, 1RS+M: 0.47, 2RS+M: 0.51. Indices: CI: 88.8, SI: 102.95; IED/HL: 18.7, IHL/AL: 62.33, Imcu: 54.24, I2RS+M/1RS+M: 109.38, I2RS+M/m-cu: 107.38.

Remarks: The big difference in body length to P. loosi is due to the low degree of telescoping of its gaster. If one compares the values of BLw/oG, the difference in size is smaller and more realistic. The preserved propodeal spine appears slightly bent downwards. This can be caused by taphonomic influences. Colour differences are not assessed as taxonomic characteristics, see Chapter: Material and Methods.

Paraphaenogaster schindleri sp. nov.

(Fig. 4a, b)

Paraphaenogaster schindleri sp. nov., gyne, holotype NHMM-PE20001/5065-LS. a Photograph, b Line drawing; Paraphaenogaster cf. schindleri, gyne, NHMM-PE2010/5462-LS. c Photograph, d Line drawing; Paraphaenogaster cf. schindleri, gyne, NHMM-PE2002/5019-LS. e Photograph, f Line drawing; detail: head with left antenna, see Supplementary Data 1: Fig. 5.

Etymology: Honouring Dr. Thomas Schindler, who developed essential models for the formation and sedimentological development of Lake Enspel and other Oligocene Lager-stätten in the Westerwald Mountains through time.

Holotype: NHMM-PE2001/5065-LS, winged gyne.

Position: Head dorsal, alitrunk dorsolateral, petiole lateral, postpetiole dorsolateral, gaster dorsolateral.

Colour: Black.

Type locality and horizon: Enspel Oilshale, Rhineland-Palatinate, Germany. Enspel Formation, Upper Oligocene, MP 28; (24.56–24.79 Ma, Mertz et al. 2007), layer S16.

Description: Gyne. BL about 11.74. Head longer than wide, with almost parallel sides, and distinct occipital corners. Head does not get narrower towards the front. Posterior margin of head median with a smooth depression. Long straight frontal carinae reaches beyond the median ocellus. All dorsal parts of head completely sculptured with constant longitudinal striae. Eyes located at about midlength of head. Eyes relatively small, head more than five times longer than maximum eye diameter. Gena striated. Anterior clypeal margin smooth, median convexly shaped. Clypeus densely striated. Fronto-clypeal-suture median convex, frontal triangle distinctly reaching beyond frontal lobes. Mandibles triangular. Masticatory margin with 6–8 triangular-shaped teeth. Teeth 5 and 6 seem to be slightly smaller than the others. Most apical parts of mandibles hidden in the sediment. Therefore there is no evidence for the existence of one or two distinctly enlarged and curved apical teeth. Scape just reaches posterior margin of head. Scape widely curved at base. Funiculus 11-segmented. The six proximal segments are almost as long as wide, slightly increasing in size towards apex. The six apical funicular segments continuously slightly increasing length towards apex, but they do not form a differentiated club. Alitrunk high, not arched. Scutum large, flat, overlaps pronotum anteriorly, antero-lateral corners of pronotum not visible from dorsal. Scutellum is transversely oval shaped with tapered ends. Its anterior margin is upraised (could also be caused by taphonomic processes). Propodeal declivity fairly steep. Well-developed metanotum, its posterior margin is distinctly thickened. Propodeal spines only recognisable as outlines. Propodeum could be slightly angled, provided with small pointed corners. Scutum is striated, straight in the middle, slantwise to both sides. Latter converge towards tegula. Scutellum also with coarse longitudinal ridges. Signs of tibial spurs found at all legs, simple at mid and hind legs, broader and probably brushed at foreleg. Tarsal segments of all legs with bristles. Wing venation with closed cells mcu and 1+2r. Shape of cell mcu distinctly trapezoid. Vein 1Cu almost double length of 1RS + M. In other respects, the description of the wing venation of the genus applies. Propodeum with transversal striation at posterior declivity, continuing vertical at lateral parts of propodeum. Solid, round propodeal-petiolar articulation, protrudes from alitrunk. Petiole pedunculate, very stout. In profile, it appears dorsally convex. Dorsal part of petiolar node is incomplete. Postpetiole with distinct node. Ascent and descent of node medium. The node’s top seems to have another surface structure; it stands out from the rest of the postpetiole. This probably also applies for the petiole top. Helcium projects ventrally at less then mid length of petiole's anterior face. Maximum height of petiole and postpetiole is about equal. Gaster is not complete. Posterior margins of first gastral tergite and sternite are not clear because of break lines.

Measurements: Holotype NHMM-PE20001/5065-LS; BLw/oG: 8.61, HL: 2.51, HW: 2.15, ED: 0.35, GeL: 0.68, ML: 1.47, MML: 0.76, SL: 2.02, AL: 3.74, ScuL: 1.75, ScutL: 0.68, FWL: 10.08, HiTL: 2.14, PL: 1.03, PH: 0.69, PPL: 0.56, PPH: 0.78, HeH: 0.35, Wing venation: 2M+Cu: 0.90, 1Cu: 0.93, 1M: 0.63, m-cu: 0.78, 1RS+M: 0.50, 2RS+M: 0.56. Indices: CI: 85.71, SI: 93.7, IED/HL: 14.05, IHL/AL: 67.17, Imcu: 53.97, I2RS+M/1RS+M: 111.76, I2RS+M/m-cu: 133.86, I2RS+M/2M+Cu: 62.30.

Differential diagnosis: P. schindleri differs from P. loosi by its well defined occipital corners and its long, almost parallel running frontal carinae. It is not allocated to the genus Messor because CI in Messor gyne is in most species distinctly above 100. (Measurements on images from the Antweb of ten gynes from ten different extant Messor species showed an average CI of more than 106.) Also the outer line of the mandibles is not nearly as strongly bent as with the extant Messor gyne. In addition, the central backward area of the clypeus and the frontal triangle do not reach the width seen with the extant Messor gynes. Therefore, there is no strong reason to assign this sample to the genus Messor. Comparisons with fossil Messor species are hardly possible. So far, only one fossil Messor species has been described: Messor sculpturatus, Carpenter 1930 from the late Eocene deposit in Florissant, USA. This assignment, however, is equivocal and it has been generally questioned by Bolton (1982: p. 341), later Bolton (1995: p. 257) classified it as insertae sedis in Messor.

Paraphaenogaster cf. schindleri

(Fig. 4c, d)

Specimen: NHMM-PE2010/5462-LS, winged gyne.

Position: Head, alitrunk, and petiole dorsal, postpetiole and first gastral segment dorsolateral. Colour: ?Dark brown to black.

Type locality and horizon: Enspel Oilshale, Rhineland-Palatinate, Germany. Enspel Formation, Upper Oligocene, MP 28; (24.56–24.79 Ma, Mertz et al. 2007), layer S6-10.

Description: BL about 11.41. Head slightly longer than wide. Median anterior margin of clypeus smooth, convex shaped. Head sides almost parallel. Posterior margin of head is not well preserved; it is visible only as a shadow. Location of eyes is about mid length of head. Mandibles triangular; masticatory margin with 6–8 triangular teeth of subequal size. There is no evidence for the existence of longer apical curved teeth. Scape just reaches posterior margin of head. Dorsal parts of head that are preserved are completely sculptured with regular longitudinal striae. Towards occiput it turns into a reticulate pattern. Antenna with 12 segments, with a weak 4-segmented club. Alitrunk slender. Medioanterior part of scutum slightly rugose, rest of scutum with fine striae, slantwise to both sides, straight in the middle. Scutellum oval shaped with tapered ends; its sculpture is punctated and roughly rugose. Prescutellum distinct, with longitudinal striae. Well-developed metanotum. Propodeum with horizontal striae. Cuticle of propodeum shows triangle-like acute structures. As these do not follow any pattern, they are most likely caused by taphonomic processes. Propodeal spines unclear. No tibial spurs found at fore and mid leg. Preservation of wings poor. Wing venation with closed cells mcu and 1+2r. Shape of cell mcu trapezoid. Distal parts of forewings not well preserved. Therefore, cell 3r remains unclear. Vein rs-m very thin, sclerotization lacking. As other veins are preserved, it is likely that the vein rs-m is primarily strongly reduced. Petiole elongate with long peduncle ending in a petiolar node. Due to the caudo-dorsolateral perspective on the petiolar node and the fractures it contains, its shape cannot be clearly determined. Postpetiole with distinct node. Anterior face of its node steeply ascending, node distinctly tapered transversely to the body axis, forming a ridge. Posterior face of node much shorter, gradually descending. Helcium projects from low down of the anterior face of the postpetiole. Only first gastral tergite preserved, its sculpture is rugose.

Measurements: NHMM-PE2010/5462-LS; BLw/oG: 8.09; HL: 2.41, HW: 2.31, ED: 0.31 (?), GeL: 0.31, ML: 1.55, MML: 0.76, SL: 1.86, AL: 3.03, AW: 1.84, ScuL: 1.49, ScutL: 0.47, FWL: 9.0, HiTL: 1, 98, PL: 1.15, PPL: 0.74, G1L: 2.48. Indices: CI 95.74, SI: 80.77, IED/HL: 13.43(?), IHL/AL: 79.54.

Remarks: Unfortunately, central parts of the head, like posteriorly extending area of the clypeus and the frontal triangle, are not preserved. Also, it is not clear if this species has two almost parallel running long carinae like P. schindleri. As this specimen has some characteristics, like body size, shapes of head, mandibles, petiole and postpetiole in common with P. schindleri, it is specified as Paraphaenogaster cf. schindleri. It is not allocated to the genus Messor because CI in extant Messor gyne is in most species distinctly above 100. Also, outer lines of mandibles are not strongly bend. An assignment to the genus Aphaenogaster is not strongly supported. Neither by the relatively high CI nor by its petiole shape, nor by its wing venation pattern. Vein rs-m is very weak.

Paraphaenogaster cf. schindleri

(Fig. 4e, f)

Specimen: NHMM-PE2002/5019-LS, winged gyne.

Position: Head, alitrunk petioli, and gaster from lateroventral.

Colour: Black.

Type locality and horizon: Enspel Oilshale, Rhineland-Palatinate, Germany. Enspel Formation, Upper Oligocene, MP 28; (24.56–24.79 Ma, Mertz et al. 2007), layer S14.

Description: Gyne. BL about 12.65. Head elongate, with well-developed occipital corners. Head parallel at sides, eyes appear slightly sunken at about mid length of head. Mandibles triangular, more than six teeth. Apical and preapical teeth clearly bigger than the others, sharp and claw-like curved. Other teeth are shaped triangular and of almost equal size. Antenna with 12 segments. Funiculus slender without distinct club. Pedicellus erroneously appears two-segmented. Scape just reaches occipital margin of head. Scape with continuously increasing width towards distal. Anterior part of laterocervical plates of the propleura well preserved. Wing venation with closed cells mcu and 1+2r. Shape of cell mcu is strongly trapezoid. Vein 1Cu twice as long as 1RS + M. In all other respects, the description of the wing venation of the genus applies. Due to the dorsoventral position of the fossil, it is not clear if there are propodeal spines developed. Tarsal segments of mid and hind legs with bristles. Petiole partly hidden in sediment, visible parts indicate a stout pedunculate petiole. Postpetiole seen from lateroventral elongate, most likely with flat node. It is broadly connected with petiole. Gaster elongate, first gastral segment distinctly longer than the others, reaches half-length of gaster. Gastral tergites covering lateral and lateroventral parts of gaster. However, this impression could also be caused by deformation.

Measurements: NHMM-PE2002-5019-LS; BLw/oG: 8.56; HL: 2.56, HW: 2.36, ED: 0.56, ML: 1.16, MML: 0.68, SL: 1. 93, AL: 3.44, FWL: 10.31, HiTL: 2.31, PL: 1.10, PH: 0.81, PPL: 0.78, HeH: 0.54, G1L: 2.49, G1W: 2.56. Wing venation: 2M+ Cu: 1.01, 1Cu: 1.04, 1M: 0.54, m-cu: 0.71, 1RS+M: 0.51, 2RS+M: 0.56. Indices: CI: 92.0, SI: 81.91, IED/HL: 21.8; IHL/AL: 74.64, Imcu: 49.3, I2RS+M/1RS+M: 108.57, I2RS+M/m-cu: 126.51, I2RS+M/2M+Cu: 55.07.

Remarks: This specimen resembles P. schindleri in body length, head size and head shape, the latter especially with regard to the occipital corners. Although dorsal side of head cannot be seen, an assignment as Paraphaenogaster cf. schindleri appears to be appropriate.

Paraphaenogaster bizeri sp. nov.

(Fig. 5a, b)

Paraphaenogaster bizeri sp. nov., gyne, holotype NHMM-PE1997/5991-LS. a Photograph, b Line drawing, detail: head, see Supplementary Data 1: Fig. 6; Paraphaenogaster incertae sedis, gyne, NHMM-PE1995/5175-LS. c Photograph, d Line drawing, detail: petiole and postpetiole, see Supplementary Data 1: Fig. 7

Etymology: Honouring Thomas Bizer, Mainz, Germany, who managed the photographic repository of the Enspel excavations and did the image processing for many Enspel papers, published by the staff of the General Department for the Conservation of the Cultural Heritage of Rhineland Palatinate, Department Archaeology/History of the Earth, Mainz (Germany).

Holotype: NHMM-PE1997/5991-LS, winged gyne.

Position: Head, alitrunk, petiole, postpetiole, first gastral tergite dorsal. Worth mentioning is the fact that left mandible is extremely arched because of a surface distortion in the sediment.

Colour: Black. Alitrunk, petiole, postpetiole, and gaster pyritized.

Type locality and horizon: Enspel Oilshale, Rhineland-Palatinate, Germany. Enspel Formation, Upper Oligocene, MP 28; (24.56–24.79 Ma, Mertz et al. 2007), layer S14 o.

Description: BL about 11.5. Head slightly wider than long, with rounded occipital corners. Head tapers anteriorly. Median part of anterior clypeus margin is smooth and follows strongly convex curve. Ridges of striae are reaching anterior margin. The posterior margin of the head shows median a small pointed depression. Frontal carinae reaching back to about mid length of eyes. Frontal lobes do not cover antennal condyle completely. All dorsal parts of head, completely sculptured with constant longitudinal, fairly fine striae, at occiput it turns to a reticulate pattern. Frons wide. Mandibles sub-triangular. Masticatory margin with about 8 triangular shaped teeth, all about the same size. Apical tooth not preserved, but signs in the sediment indicate a bigger apical tooth. Eyes located at midlength of head. Eyes diameter is only about 17% of head length. Scape reaches posterior margin of head. Antenna with 12 segments. No differentiated club. Alitrunk partly pyritized. Scutellum is transverse oval with tapered ends. Well-developed metanotum. Posterior margin of metanotum distinctly thickened. Scutum longitudinally striated. Scutellum with coarse longitudinal ridges. Propodeum with transversal striation at posterior declivity continuing vertical at lateral parts of propodeum. Propodeal spines not preserved, but according to photograph analysis very likely. Petiole with long, stout peduncle and a dinstinct high petiolar node. Peduncle appears ventrally and laterally slightly concave. Peduncle lateral with two long ridges and a groove in between. Postpetiole wide, with distinct node. Anterior face of node moderately ascending, rounded top. Posterior face of node much shorter, gradually descending. Helcium articulates ventrally at less then mid length of posterior face of petiole. Wing venation with closed cells mcu, 1+2r, and 3r. Vein rs-m weak, not distinct, sclerotization at junction with vein 4M only. Shape of cell mcu trapezoid. Vein 5RS does reach the apical margin of wing, but it is very weakly sclerotized in its distal part. Additional incomplete vein is leaving proximally from 2-3rs. In all other respects, the description of the genus applies. First gastral tergite large, with homogenous slightly rugose surface sculpturing.

Measurements: Holotype NHMM-PE1997/5991-LS; BLw/oG: 7.80, HL: 2.05, HW: 2.14, ED: 0.35, GeL: 0.85, ML: 1.18, MML: 0.74, SL: 1.73, AL: 3.12, FWL: 8.23, ScuL: 1.36, ScutL: 0.56, HiTL: 2.08, PL: 1.15, PPL: 0.75, PPW: 0.88, G1W: 3.06. Wing venation: 2M+Cu: 0.91, 1Cu: 0.82, 1M: 0.62, m-cu: 0.62, 1RS+M: 0.49, 2RS+M: 0.47. Indices: CI: 104.44. SI: 80.83, IED/HL: 17.26, IHL/AL: 65.55, Imcu: 58.93, I2RS+M/1RS+M: 96.97, I2RS+M/m-cu: 108.85, I2RS+M/2M+Cu: 51.61.

Differential diagnosis: P. bizeri is characterised by its combination of BL 11-12 mm, its posteriorly wide head, narrowing towards the front, its rounded and distinct occipital corners, and its relatively small eyes. Its head is sculptured with regular, relatively fine striae, including the clypeus. It differs from P. tertiaria by its head shape, eyes position and shape of the lateral parts of the anterior clypeal margin. The head shape of P. tertiaria is characterised by “….parallel sides and rounded occipital margin, without occipital angles” (Dlussky and Putyatina 2014, p: 273). It differs from P. jurei (Heer 1849) regarding its size and head shape (see also Dlussky and Putyatina 2014, p. 271).

Paraphaenogaster incertae sedis

(Fig. 5c, d)

Specimen: NHMM-PE1995/5175-LS, winged gyne.

Formicidae indet. Wedmann 2000: 68, Fig. 23 (wing).

Position: Parts of alitrunk, petiole, postpetiole, and parts of gaster from lateral, one forewing. Head and legs are missing.

Colour: Black.

Type locality and horizon: Enspel Oilshale, Rhineland-Palatinate, Germany. Enspel Formation, Upper Oligocene, MP 28; (24.56–24.79 Ma, Mertz et al. 2007), layer S16.

Description: BL > 11. Head is missing. Alitrunk stout, high, arched. Scutum strongly arched. Scutellum thickened, and distinctly upraised. Metanotum distinct. Marks of propodeal spines existing, fractures of broken spine can be identified. Petiole with stout peduncle. Peduncle not bar-like; there is a smooth transition from peduncle to node. Node is continuously ascending, anterior face shaped slightly convexly. Node slightly tapered, with rounded top. Postpetiole stout, with gradually arising and descending node. Its node is less high than the petiole’s node. Solid, high helcium articulates higher than mid length at posterior face of petiole. Wing venation with closed cells mcu and 1+2r. Cell mcu trapezoid shaped. Vein 5RS does reach the apical margin of wing, but it is very weakly sclerotized in its distal part. 1RS distinctly inclining distad. Wing venation pattern follows in all other aspects the description of the genus. First gaster distinctly longer than the others, with homogenous sculpture, probably not shiny.

Measurements: NHMM-PE1995/5175-LS; AL: 3.7, AH: 2.9, FWL: 10.38, PL: 1.18, PH: 0.96, PPL: 0.66, PPH: 0.9, HeH: 0.51, G1L: 2.91, G1H: 2.23. Wing venation: 2M+Cu: 0.93, 1Cu: 0.97, 1M: 0.65, m-cu: 0.72, 1RS+M: 0.54, 2RS+M: 0.47. Indices: Imcu: 56.06; I2RS+M/1RS+M: 86.49, I2RS+M/m-cu: 119.15, I2RS+M/2M+Cu: 50.79.

Remarks: This specimen most probably has a BL > 11. Based on the combination of an arched mesonotum, protruding scutellum, its petiole and postpetiole shape and its wing venation pattern; this specimen is allocated to the genus Paraphaenogaster. As the head is completely missing, specimen cannot be assigned more precisely.

Paraphaenogaster freihauti sp. nov.

(Fig. 6a, b)

Etymology: Honouring Bernd Freihaut, Darmstadt, a distinguished architect, who run the project to develop the Fossil-Lagerstätte Enspel and an industrial heritage of basalt mining to the famous touristic site Stöffel-Park (Enspel, Westerwald Mountains, Germany).

Holotype: NHMM-PE1995/8758-LS, worker.

Position: Head, alitrunk from dorsolateral, petiole, postpetiole and gaster from lateral.

Colour: Head, alitrunk and first gastral segment dark brown to black, petiole and postpetiole, gastral segments 2–4, and legs medium brown.

Type locality and horizon: Enspel Oilshale, Rhineland-Palatinate, Germany. Enspel Formation, Upper Oligocene, MP 28; (24.56–24.79 Ma, Mertz et al. 2007), layer S14.

Diagnosis: BL about 6.14. Head longer than wide, with smoothly rounded occipital corners. Head sides are slightly convex. Strong gena. Eyes located behind mid length of head. Eyes diameter is about 14.3% of head length. Mandibles stout, sub-triangular, with 7–8 teeth. Teeth have approximately the same size. Antenna hardly preserved, only some funicular segments preserved. The anterior margin of clypeus is smooth. Head with distinct longitudinal striae. Alitrunk elongate, slender. Promesonotum dome-shaped, pronotum sculptured longitudinal rugose. Along the middle of the pronotum, there is a deep longitudinal groove, but it is not clear if this is a morphological or a taphonomical feature. Dorsal profile line of propodeum distinctly lower than arched promesonotum. Propodeal spines short, acute, triangular, widened at base. Petiole with distinct peduncle that gradually developes into a tapered rounded node. Although link between peduncle and propodeum is partly disarticulated and morphology gets unclear, a small projection at anteroventral part of peduncle is indicated. Postpetiole in profile with smoothly rounded node. Postpetioles node not as high as petioles node. Helcium articulates at more than half of posterior face of petiole. Gaster complete. First gastral segment far the longest of all gastral segments, reaches slightly more than half-length of gaster.

Measurements: Holotype NHMM-PE1995/8758-LS, BLw/oG: 4.25, HL: 1.34, HW: 1.24, ED: 0.19, GeL: 0.60, ML: 0.63, MML: 0.32, AL: 1.7, AH: 0.98, HiTL: 1.55, PL: 0.54, PH: 0.37, PPL: 0.34, PPH: 0.34, HeH: 0.22, G1L: 1.28, GL: 1.89. Indices: CI 92.31, IED/HL: 14.29, IHL/AL: 78.52.

Differential diagnosis: There are no fossil Paraphaenogaster nor Aphaenogaster worker from Oligocene known yet. The two Aphaenogaster species A. maculate (Theobald 1937) and A. maculipes (Theobald 1937), known from the late Oligocene, are gynes. Radchenko and Perkovsky (2016) informally allocated these species to the genus Paraphaenogaster. Since worker do not have wings, the main differentiating feature to allocate the genus is missing. So genus allocation is based on an assumption. For completeness and as a precaution, a comparision with all known Aphaenogaster workers is done herein. This species resembles A. sommerfeldti Mayr 1868 in its body contours. But sculpture of head differs. Head sculpture of A. sommerfeldti Mayr 1868 is described as fine wrinkled dots. P. freihauti shows distinct longitudinal striae at head. It clearly differs from A. oligocenica Wheeler 1915 and A. mersa Wheeler 1915 because their promesonotum is not raised. In addition, head and alitrunk sculpture differs in A. mersa and P. freihauti. A. amphioceanica De Andrade 1995 is characterised by an elongated head and neck which are missing here. A. dlusskyana Radchenko and Perkovsky 2016 is bearing elongate-triangular mandibles and long spines in contrast to P. freihauti. Also A. praerelicta De Andrade 1995 from the Mexican amber shows long propodeal spines. In A. antiqua (in Dlussky and Perkovsky 2002), propodeal spines are not widened at base, additionally, antennal segments 2–7 seem to be very short compared to those in P. freihauti.

Paraphaenogaster wettlauferi sp. nov.

(Fig. 6c, d)

Etymology: Honouring Michaela Wettlaufer, Alsfeld (Germany), who treated conservatively most of the fossil insects from Lake Enspel.

Holotype: NHMM-PE1995/5604-LS, worker.

Position: Head dorsal, alitrunk dorsolateral, petiole, postpetiole from lateral, gaster from lateroventral.

Colour: Body black, well sclerotized; legs dark brown.

Type locality and horizon: Enspel Oilshale, Rhineland-Palatinate, Germany. Enspel Formation, Upper Oligocene, MP 28; (24.56–24.79 Ma, Mertz et al. 2007), layer S16.

Diagnosis: BL about 8.18. Head slightly elongated, wider posteriorly than anteriorly. Occipital corners rounded. Head sides slightly convex. Eyes located above mid length of head. Eyes small, their diameter is about 8.4% of head length. Mandibles stout, triangular, with approximately eight small teeth, subequal in size. There is no clear evidence for a big apical tooth. Scape exceeds occipital margin of head. Scape bended at base. Funiculus most likely with 11 segments, 3–4 apical segments somehow larger, forming a weak club. Anterior margin of clypeus median smoothly convex. Irregularities are interpreted as being caused by fossilization processes. Frontal lobes flat, weakly convex. Head sculptured with longitudinal rugae. Alitrunk elongate, slender. Pronotum and mesonotum clearly separated by promesonotal suture. Mesonotum convex in profile and higher than pronotum. Metanotal groove present. Short, relatively blunt spines project from the posterior face of the propodeum. Petiole with long peduncle and distinct node. Top of node irregularly coarsely sculptured. Posterior margin of the petiole is thickened. Postpetiole with elongate helcium and a distinctly rounded node. Nodes sculpture coarsely hammered/dotted. First gastral segment is the most sclerotized, and it is the longest.

Measurements: Holotype NHMM-PE1995/5604-LS, BLw/oG: 6.07, HL: 1.92, HW: 1.75, ED: 0.16, GeL: 0.71, ML: 0.97, MML: 0.69, SL: 1.4, AL: 2.39, AH: 0.96, MesoL: 0.72, HiTL: 1.64, PL: 0.63, PH: 0.44, PPL: 0.44, PPH: 0.43, HeH: 0.26, G1L: 1.64. Indices: CI: 90.76, SI: 80.21, IED/HL: 8.41, IHL/AL: 80.57.

Differential diagnosis: P. wettlauferi is distinguished from all other known fossil Aphaenogaster species by its very small eyes.

Ten males were examined more closely. All show the typical Paraphaenogaster wing venation pattern. Males show slight differences in shape and sculpture of head, pronotal neck, alitrunk, petiole and postpetiole. However, these differences are considered too small to exist as an independent species under consideration of possible taphonomic influences. Only one new species is described from this variety of conservation images.

Paraphaenogaster wuttkei sp. nov.

(Fig. 7a–c)

Etymology: Honouring Dr. Michael Wuttke, former head of the Section History of the Earth at the General Department of the Cultural Heritage of Rhineland Palatinate, Department Archaeology/Section History of the Earth, Mainz (Germany), who initiated and headed the scientific excavations through 26 years at the Fossil-Lagerstätte Enspel.

Holotype: NHMM-PE1997/5513-LS, winged male.

Position: Head: dorsal, alitrunk: dorsolateral, petiole: dorsolateral, gaster: dorsal.

Colour: Dark brown to black.

Type locality and horizon: Enspel Oilshale, Rhineland-Palatinate, Germany. Enspel Formation, Upper Oligocene, MP 28; (24.56–24.79 Ma, Mertz et al. 2007), layer S16.

Description: BL about 9.23. Head longer than wide, with smoothly rounded posterior corners. Mandibles sub-triangular with six teeth. Last two apical teeth bigger than the others, which are of about the same size. Eyes are about 33.7% of head length. Eyes located laterally at about mid length of head. It looks as if the compound eye is not only oval in shape, but also has a small anterior bulge. However, this impression may also have been caused by the compaction. Further specimens of this species would be needed to verify this morphological interpretation. Antenna with short scape and filiform funiculus, 12- or 13-segmented. Funicular segment 6 and 7 almost two times longer than wide. Funiculus about 3.3 times longer than scape. Anterior clypeal margin smooth and distinctly convex. Irregularities along the margin are interpreted to be due to taphonomic influences. Along and parallel to the anterior margin, there are a few long transverse striae. Posterior margin of clypeus projects backwards. The frontal triangle is structured with short, semicircularly arranged striae and forms a rosette-like pattern. Posterior part of the rosette is raised like a ridge with rounded top. Anteriorly to this ridge, semicircular concentric circles are arranged (Fig. 7c). Frontal lobes are hardly covering base of scape. Head striated, particularly at gena and at frontal carina. Posterolateral parts of head reticulated. Alitrunk large and arched as a whole. It is sculptured almost all over with fine and dense striae. Straight striae extend obliquely at lateral and posterior parts of scutum. The anterior part of scutum shows no distinct striae. The striation pattern could follow notauli. Anterior part of scutellum slightly protruding. Proscutellum distinct, slightly recessed. Propodeum longitudinally densely striated. There is no evidence for the existence of spines. Petiole with elongate stout peduncle, increasing height towards distal, rounded top posteriorly. Ventral part of peduncle expands anteriorly so alitrunk-petiole connection seems to be particularly wide and solid. This anterior ventral extension, however, could also have been caused by extreme flattening during the fossilization process. Postpetiole disarticulated from petiole and incomplete. Two longitudinal ridges can be identified on postpetiole’s node. Forewing with closed cells: mcu and 1+2r. Pterostigma well developed. Cell mcu triangular. Wing venation pattern follows in all other aspects the description of the genus. Parts of first gastral segment preserved. Sculpture of first gastral tergite not specific, shiny.

Measurements: Holotype NHMM-PE1997/5513-LS; BLw/oG: 6.2, HL 1.44, HW: 1.34, ED: 0.49, GeL: 0.29, ML: 0.66, MML: 0.29, AL: 3.15, ScuL: 1.27, ScutL: 0.44, HiTL: 2.64, FWL: 9.08, PL: 0.82, PH: 0.5, G1L: 1.53. Wing venation: 2M+Cu: 0.69, 1Cu: 0.84, 1M: 0.47, m-cu: 0.62, 1RS+M: 0.56, 2RS+M: 0.31. Indices: CI: 92.86, IED/HL: 33.67, IHL/AL: 45.75, Imcu: 66.67, I2RS+M/1RS+M: 55.26, I2RS+M/m-cu: 92.67, I2RS+M/2M+Cu: 44.68.

Differential diagnosis: P. wuttkei is characterised by its complex sculpture in the central part of the clypeus and the frontal triangle. With regard to combination with its body length (BLw/oG: 6.34) and its forewing length (FWL < 0.9), this species differs from the other Paraphaenogaster males described here. As it is not clear, if the remarkable wide anterior part of the petiole is natural or caused by taphonomic processes, it will not be taken as a specific morphologic feature. Since the alitrunk is seen from dorsal, it is not clear if the pronotum is anteriorly extended into a neck-like shape.

Paraphaenogaster cf. wuttkei

(Fig. 7d, e)

Specimen: NHMM-PE1995/6227-LS, winged male.

Type locality and horizon: Enspel Oilshale, Rhineland-Palatinate, Germany. Enspel Formation, Upper Oligocene, MP 28; (24.56–24.79 Ma, Mertz et al. 2007), layer S16.

Position: Head, alitrunk dorsal, petiole lateroventral; postpetiole dorsolateral, parts of alitrunk and complete gaster missing.

Colour: Dark brown to black.

Description: BL about 8.9 (estimated, because gaster is missing). Head slightly wider than long, with rounded posterior corners. Mandibles sub-triangular with 6–7 teeth at masticatory margin. First two apical teeth bigger than the others, slightly curved. Other 4–5 teeth decrease slightly in size towards basal angle of mandible, on right mandible; however, the third apical tooth is smaller than the following ones. Eyes big, oval, located below mid length of head. Eye diameter is about 40% of head length. Anterior clypeal margin smooth, convex. Posterior clypeal margin projecting backwards. Antennal sockets are close together. Between antennal sockets a transverse clypeal beal ascends. Additional sculpture of the median part of the clypeus seams to be complex; it is striated and sculptured but the exact pattern cannot be identified. Frontal lobes straight, just covering base of scape. Scape short and relatively wide, reducing width only at base. All preserved dorsal parts of head are striated, particularly strong at gena. Alitrunk strongly deformed, only parts of scutum, pronotum and propodeum are preserved. Preserved parts of scutum partly with fine dense striae. Preserved parts of propodeum are striated as well. Petiole pedunculate, the anterior face of petiole is continuously rising straight up ending in a node. Anterior part of petiole slightly widened (width about 0.22 mm). Ventral part of petiole flat, slightly concave. Almost complete posterior face of petiole is connected with helcium of postpetiole. Helcium shows thick longitudinal striae. Postpetiole elongate, flat node with rounded top. Postpetiole shorter, but slightly higher than petiole. Petiole and postpetiole are longitudinally striated, petiole also shows laterally oblique ridges. Postpetiole’s top notched longitudinally, with thickened ridges on both sides. Forewing with closed cells: mcu and 1+2r. Cell 3r open. Pterostigma well developed. Wing venation pattern follows in all other aspects the description of the genus. Gaster almost completely missing. Preserverd parts of the presclerite of the 4th abdominal tergite show radially arranged ridges. These integumentary foldings, so called “pillars”, are interpreted as being associated with the stridulation organ.

Measurements: NHMM-PE1995/6227-LS; BLw/oG: 5.76, HL: 1.25, HW: 1.27 (head flattened), ED: 0.5, GeL: 0.24, ML: 0.60, MML: 0.29, SL: 0.59, AL: 2.67, FWL: 8.46, PL: 0.88, PH: 0.51 PPL: 0.66, PPH: 0.54 (positioned dorsolateral, measured as seen); HeH: 0.37. Wing venation: 2M+Cu: 0.69, 1Cu: 0.59, 1M: 0.41, m-cu: 0.50, 1RS+M: 0.29, 2RS+M: 0.46. Indices: CI: 101.18, IED/HL: 40.0, IHL/AL: 46.89, Imcu: 50.0, I2RS+M/1RS+M: 155.0, I2RS+M/m-cu. 95.62, I2RS+M/2M+Cu. 65.96.

The following male specimens also belong to the genus Paraphaenogaster, but do not have sufficiently distinct characteristics to warrant the designation of a new species.

Paraphaenogaster incertae sedis

(Fig. 8a)

Paraphaenogaster incertae sedis, male, NHMM- PE2001/5194-LS. a Photograph; Paraphaenogaster incertae sedis, male, NHMM- PE2010/5697-LS. b Photograph; Paraphaenogaster incertae sedis, male, NHMM- PE2010/5576-LS. c Photograph, detail: head, alitrunk, see Supplementary Data 2: Fig. 1; Paraphaenogaster incertae sedis, male, NHMM-PE2001/5160-LS. d Photograph

Specimen: NHMM-PE2001/5194-LS, male.

Type locality and horizon: Enspel Oilshale, Rhineland-Palatinate Germany. Enspel Formation, Upper Oligocene, MP 28; (24.56-24.79 Ma, Mertz et al. 2007), layer S12.

Position: Head ventral, alitrunk lateral, petiole dorsolateral, postpetiole dorsal, disarticulated, gaster partly missing.

Colour: black.

Description: BL about 8.65. Head wider than long, to both sides from ventral midline distinct longitudinal striae are running from median anterior part of the head to its lateroposterior parts. Eyes large and oval. Head and alitrunk slightly elongated forming a neck. Alitrunk large, strongly arched, scutum with distinct fine dense striae. Scutellum slightly convex. Propodeum steeply descending and densely striated. Petiole and postpetiole elongate, both without a distinct node. Postpetiole not narrowed at helcium. Petiole with long regular fine striae, postpetiole irregularly striated, rugose. Densely arranged integument foldings on presclerite of first gastral tergite, so called “pillars” preserved. First gastral tergite shiny.

Measurements: NHMM-PE2001/5194-LS; BLw/oG: 5.52 (including THL, instead of HL and MML), HL: 1.06, HW: 1.0 (est.), ED: 0.35; AL: 2.76, FWL: 6.13, ScuL: 1.49, ScutL: 0.37. PL: 0.78, PH: 0.32, PPL: 0.63, PPH: 0.40, HeH: 0.31, Wing venation: 1M: 0.38, 1Cu: 0.69, m-cu: 0.49, 1RS+M: 0.35, 2RS+M: 0.35. Indices: CI: 94.44, IED/HL: 33.33, IHL/AL: 38.41, Imcu: 51.06, I2RS+M/1RS+M: 100.0, I2RS+M/m-cu: 83.85.

Remarks: This specimen is characterised by its indication of a pronotal neck. It differs from P. wuttkei in BLw/oG (5.5 vs. 6.2 in P. wuttkei) and FWL (6.1 vs. 9.1 in P. wuttkei). The strong parallel striation on the petiole has this specimen in common with the sample NHMM-PE2001/5160-LS. The latter, however, does not show any indication of a neck.

Paraphaenogaster incertae sedis

(Fig. 8b)

Specimen: NHMM-PE2010/5697-LS, male.

Type locality and horizon: Enspel Oilshale, Rhineland-Palatinate, Germany. Enspel Formation, Upper Oligocene, MP 28; (24.56–24.79 Ma, Mertz et al. 2007), layer S16.

Position: Head ventral, alitrunk lateroventral, petiole lateral, gaster dorsal.

Colour: Black.

Description: BL about 7.79. Head longer than wide, without distinct occipital corners. Long striae starting from ventral midline heading posteriorly towards occiput. Sharp corners at the posterior part of head are being interpreted as fractures. Comparatively small eyes. Alitrunk well developed, mesonotum arched. Propodeum smoothly descending. All visible parts of alitrunk are striated, scutum shows very fine striae. Petiole’s peduncule stout, smoothly ascending towards distal, node with rounded top. Anterior part of petiole hidden; its length can therefore only be estimated. Petiole and postpetiole show dense fine longitudinally striae. Helcium narrowed, showing a distinct constriction between petiole and postpetiole. Postpetiole slightly nodiform, without a distinct dorsal notch. Gastral tergites with unspecific sculpture, not shiny. Either two or three gastral tergites are preserved. It is not clear, because the posterior margins of the tergites are not sharp. The presclerite of the 4th abdominal tergite shows a semicircled structure with radially arranged ridges. This structure, named “pillars”, is part of the stridulation organ. Semicircle’s diameter is 0.32 mm.

Measurements: NHMM-PE2010/5697-LS; BLw/oG: 5.05 (including THL, instead of HL and MML), HL: 1.10, HW: 0.9, ED: 0.38, AL: 2.51, FWL: 5.73, PL: 0.69, PH: 0.41, PPL: 0.47, PPH: 0.46, HeH: 0.26. Wing venation: 2M+Cu: 0.53, 1Cu: 0.56, 1M: 0.31, m-cu: 0.38, 1RS+M: 0.24, 2RS+M: 0.40. Indices: CI: 81.33, IED/HL: 34.67, IHL/AL: 43.87, Imcu: 42.11, I2RS+M/1RS+M: 168.75, I2RS+M/m-cu: 77.97, I2RS+M/2M+Cu: 75.0.

Remarks: The specimen NHMM-PE2010/5697-LS is characterised by its comparably nodiform postpetiole with a narrowed helcium. Postpetiole constricted towards gaster. Both petioles with fine dense striae. Postpetiole without dorsal notch. In addition, size and forewing length is comparably small (BLw/oG: 5.05, FWL: 5.7).

Paraphaenogaster incertae sedis

(Fig. 8c)

Specimen: NHMM-PE2010/5576-LS, male (photograph, see Supplementary Data 2: Fig. 1)

Type locality and horizon: Enspel Oilshale, Rhineland-Palatinate, Germany. Enspel Formation, Upper Oligocene, MP 28; (24.56–24.79 Ma, Mertz et al. 2007), layer S14 u.

Position: Head dorsal, alitrunk lateral, petiole lateroventral, only remnants of the postpetiole are preserved, only first gastral segment and the second gaster sternite are preserved.

Colour: Black, appears shiny.

Description: BL about 8.58. Head oval, with occipital corners. Head sculptured with medium dense striae. Eyes large and oval. Three ocelli preserved. Anterior margin of clypeus smooth. Frontoclypeal suture is projecting backwards between antennal sockets. Mandibles large, triangular, number of teeth unclear. The pronotum appears slightly stretched forward, but there are no clear signs of a pronotal neck. Alitrunk large, high, strongly arched, scutum with distinct fine dense striae, scutellum is not protruding. The propodeum is steeply sloping; its central dorsal part has dense, fine striae in the longitudinal direction, while they are arranged transversely at the rear of the propodeum. Petiole with long peduncule, increasing height posteriorly, no distinct node. Wing venation with closed cells mcu and 1+2r, cell 3r open. Wing venation pattern follows in all other aspects the description of the genus. Alitrunk-petiole connection is wide and solid. Postpetiole unclear. First gastral segment shiny, not much longer than the second gastral segment.

Measurements: NHMM-PE2010/5576-LS; BLw/oG: 5.7 (including THL, instead of HL and MML), HL: 1.18, HW: 1.24*, ED: 0.44, AL: 2.73, AH: 1.93, ScuL: 1.44, ScutL: 0.6, FWL: 6.27, PL: 0.94, PH: 0.44, G1L: 1.43. Wing venation: 2M+Cu: 0.56, 1Cu: 0.75, 1M: 0.41, m-cu: 0.53, 1RS + M: 0.43, 2RS + M: 0.46. Indices: CI: 105.0, IED/HL: 37.5, IHL/AL: 43.15, Imcu: 56.86, I2RS+M/1RS+M: 106.9, I2RS+M/m-cu: 98.56, I2RS+ M/2M+Cu: 81.58.

Remarks: In this specimen, the pronotum seems to be stretched forward so that it gets a neck-shaped impression, but no distinct pronotal neck seems to be developed. The head is also not extended to the back.

Paraphaenogaster incertae sedis

(Fig. 8d)

Specimen: NHMM-PE2001/5160-LS, male.

Type locality and horizon: Enspel Oilshale, Rhineland-Palatinate, Germany. Enspel Formation, Upper Oligocene, MP 28; (24.56–24.79 Ma, Mertz et al. 2007), layer S12.

Position: Head dorsal, alitrunk lateral, petiole and postpetiole dorsolateral, gaster strongly damaged, wings only partly preserved.

Colour: Black.

Description: BL about 7.76. Head shaped triangular, wider than long. Eyes large and oval. There is no clear indication for a neck. Alitrunk high and large. Scutum strongly arched. Scutellum not protruding. Propodeum with moderate slope. No spines. Each preserved part of alitrunk with fine striae. Wings only partly preserved. However, veins 2RS+M, 2-3RS and 3M can be clearly identified and show the proportions typical for Paraphaenogaster. Cell rm is not present. Petiole elongate, flat node. Anterior part of petiole not widened. Posterior margins of petiole and postpetiole seem to be thickened. Postpetiole broadly connected with petiole, only weak constriction at helcium. Postpetiole shorter than petiole, slightly increasing height towards distal. Petiole and postpetiole with strongly pronounced regular striae. Postpetiole’s top with an indication of two ridges. At anterior margin of first gastral tergite so called “pillar” preserved.

Measurements: NHMM-PE2001/5160-LS; BLw/oG: 5.03(including THL, instead of HL and MML), HW: 1.15, AL: 2, 58, AH: 1.67, ScuL: 1.22, PL: 0.87, PH: 0.47, PPL: 0.47, PPH: 0.51, HeH: 0.37.

Remarks: This specimen differs from all other Paraphaenogaster males by a combination of its slender petiole, which ends posteriorly in a flat node, the barely constricted helcium, the strong regular striation and the thickened posterior margins of both petioles.

Paraphaenogaster incertae sedis

Specimen: NHMM-PE1995/7286-LS, male; (photograph, see Supplementary Data 2: Fig. 2).

Position: Body parts are preserved in different positions: head lateroventral, alitrunk lateral (deformed), petiole and postpetiole lateroventral, gaster dorsal.

Colour: Dark brown to black.

Description: BL estimated 8.75. Alitrunk with steep descending propodeum. No spines. All visible parts of alitrunk show medium fine striae. There is no indication for a neck.