Abstract

A study on the fracture characteristics of unmodified and chemically modified Scots pine (Pinus sylvestris) is presented. The investigated material consisted of small-dimension sawn timber originating from young logs (thinnings), aged 30–40 years. The modified samples were acetylated with acetic anhydride in an industrial scale process without the use of any catalyst, reaching an acetyl content of approximately 20%. Clear wood specimens, consisting of either heartwood or sapwood, were extracted and conditioned to equilibrium at a relative humidity of 60% and a temperature of 20 °C. The fracture energy for mode I loading in tension perpendicular to the grain was determined using single edge notched beam (SENB) specimens, subjected to three-point bending. Additionally, the modulus of elasticity along the grain and the tensile strength perpendicular to the grain were determined for sapwood specimens. The findings demonstrated a significant decrease (between 36 and 50%) in the fracture energy for the acetylated specimens, compared to the unmodified specimens. No significant effect of the acetylation process on the modulus of elasticity, nor on the tensile strength could be concluded. This study indicates that the acetylation process used results in an increased brittleness for Scots pine. Further studies are needed to analyse why the fracture energy is impaired, and to examine whether and how current timber engineering design provisions can or should be revised to account for the increased brittleness of acetylated Scots pine.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Softwoods demonstrate low durability and poor dimensional stability when exposed to changes in moisture content, resulting in, for example, crack initiation caused by differential swelling, or loss of strength due to biological degradation. To overcome these drawbacks, without the use of toxic preservatives, different modification methods have been developed. The foundation of chemical modification methods lies in the possibility to change the properties of wood by changing its chemistry and these methods have proven to be successful in limiting the hygroscopic characteristics of wood (Rowell 2006). As there is a change in chemistry of the cell wall polymers, there also is an impact on the physical properties of the wood (Rowell 1996).

Acetylation is one of the most studied chemical modification methods (Rowell 2006) and was introduced in Germany in 1928 by Fuchs (1928). The chemical process of acetylation involves a reaction of acetic anhydride with wood polymers, resulting in the esterification of accessible hydroxyl groups in the cell wall, as well as formation of the by-product acetic acid. The acetylation process is a single-addition reaction, meaning that one acetyl group is bound to one hydroxyl group, without any polymerisation (Rowell 1983). The number of free hydroxyl groups that normally bind water is reduced and substituted by hydrophobic acetyl groups. The combination of a lesser number of accessible hydroxyl groups and more hydrophobic fibres decreases the water sorption. This change in hygroscopicity results in a reduced equilibrium moisture content (EMC) and fibre saturation point (FSP) (Rowell 2006). Furthermore, acetylation impacts the wood volume. For acetylated wood with a weight percentage gain of approximately 20%, the oven-dry wood volume equals the original green volume. Hence, as the wood is in a permanently swollen state, acetylated wood exhibits fewer fibres per cross-section area, compared to its unmodified state (Rowell 1996).

Comprehensive studies have shown that acetylated wood exhibits enhanced dimensional stability and improved resistance to biological degradation; for compilations of studies see for example Rowell (1983), Rowell (2006) and Brelid (2013). Changing the chemical constitution of the cell wall polymers may also impact mechanical properties. For modified wood, well-studied mechanical properties are the modulus of elasticity (MOE) and modulus of rupture (MOR), determined through bending tests (see e.g. Dreher et al. 1964; Larsson and Simonson 1994; Bongers and Beckers 2003; Epmeier and Kliger 2005). Findings depend on wood species, climate conditions and utilised acetylation techniques. Previous studies have also reported that acetylated wood demonstrates improved hardness (Dreher et al. 1964; Bongers and Beckers 2003), improved compressive strength parallel and perpendicular to the grain (Dreher et al. 1964; Bongers and Beckers 2003), improved wet compressive strength (Goldstein et al. 1961) and a reduced relative creep, measured under cyclic relative humidity conditions (Epmeier and Kliger 2005). Insignificant effects from acetylation have been concluded regarding the impact strength (Goldstein et al. 1961; Bongers and Beckers 2003), while significant reductions in the shear strength have been demonstrated for various wood species (Dreher et al. 1964).

Whilst the effects of acetylation on dimensional stability, durability and basic mechanical properties have been investigated extensively over the last decades, less research concerning fracture properties has been performed. The occurrence of knots, holes, notches, moisture gradients etc., can induce large tensile stresses perpendicular to grain in structural elements which may lead to crack initiation and propagation (Gustafsson 2003). It is thus important to consider fracture properties when wood is used for structural applications. In the design of mechanical joints, fracture properties related to mode I and II are decisive, for example, when a load is applied at an angle to the grain, or in order to avoid brittle failure modes, such as splitting (Ehlbeck and Görlacher 2017). In particular, dowel-type joints have been researched in terms of brittle failure modes, for which both mode I and mode II fracture energy are of importance for the load bearing capacity (Sjödin and Serrano 2008; Jensen and Quenneville 2011; Cabrero et al. 2019). A study conducted by Reiterer and Sinn (2002) indicates a reduction in the mode I fracture energy with approximately 20% for acetylated spruce. The study also includes fracture characteristics of heat-treated spruce specimens, indicating even larger reductions in the fracture energy, in the order of 50%–80%.

The aim of this study is to further investigate the effects of acetylation on the fracture characteristics of wood, namely Scots pine. In the current paper, the term “fracture characteristics” refers to those material parameters that influence the brittleness of the material, i.e. strength, stiffness and fracture energy. The work includes studies on the fracture energy for mode I loading in tension perpendicular to the grain, modulus of elasticity along the grain and tensile strength perpendicular to the grain for modified and unmodified specimens. The fracture energy is determined for specimens consisting of either sapwood or heartwood, whereas the stiffness and strength are only determined for specimens consisting of sapwood. The investigated material consists of wood from young logs from thinnings. Such wood is rarely used for structural purposes due to its poor durability and poor dimensional stability. By acetylation, the aim is to enhance both durability and dimensional stability. If it is possible to do so, without impairing the mechanical properties, it will enable the use of young Scots pine in outdoor load-bearing applications.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Materials

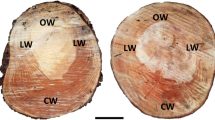

This study investigates fracture characteristics of unmodified and modified samples of young Scots pine (Pinus sylvestris). The wood was provided by the sawmill Isojoen Saha, located in Finland. The logs used by the sawmill origins within 60 km from the mill, in an area well known for its fast-growing pine. For this study, the term young logs refers to wood from small-dimension sawn timber from thinnings, with an age of approximately 30–40 years, without visible unsound knots. The modification was conducted in a proprietary industrial scale process at Accsys Group’s acetylation plant in Arnhem, the Netherlands. The size of the boards was approximately 100 mm × 1000 mm × 30 mm, in the width, length and thickness directions, respectively. The acetylation process involves a reaction of the wood with acetic anhydride at an elevated temperature (approximately 120–130 °C) without the use of any catalyst, and after the reaction, the by-product acetic acid was removed (Rowell and Dickerson 2014). The wood material was acetylated according to the commercial production process for Accoya® radiata pine at Accsys Technologies, according to the standard process (European Patent No. 2818287A1, Giotra 2014). This process is developed for radiata pine, and it should be noted that it was not optimised for Scots pine. All boards used in this study were analysed for acetyl content by near infrared spectroscopy (NIRS) according to the method described by Schwanninger et al (2011). The analysis showed that all boards reached an acetyl content of approximately 20%.

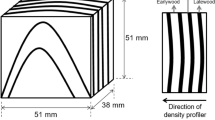

The sawing pattern to extract specimens from each board is illustrated in Fig. 1. From each board three sticks were extracted. The two outermost, furthest from the pith, contained pure sapwood (SW), based on an ocular distinction between sapwood and heartwood. The inner one contained growth rings closer to the pith, i.e. contained higher fractions of juvenile wood and heartwood. Due to the variability in performance of heartwood as well as juvenile wood, results from these specimens are presented separately from pure sapwood specimens, henceforth referred to as heartwood specimens (HW). Aiming at identifying mechanical properties for clear wood specimens, knots and other imperfections were excluded when extracting specimens from each stick. Specimens originating from the same stick are referred to as nominally equal, due to similarities regarding growth ring orientations and expected limited variation in properties in general.

The fracture energy was determined for both sapwood and heartwood, based on four test groups: unmodified sapwood (USW); modified sapwood (MSW); unmodified heartwood (UHW); modified heartwood (MHW). The modulus of elasticity and the tensile strength were only determined for sapwood, based on two test groups: USW; MSW. The density was determined for each specimen, and the moisture content (MC) for one specimen in each series of nominally equal samples, i.e. one specimen per stick, see Fig. 1. The moisture content was determined by the oven dry method. Prior to testing, all samples were conditioned until equilibrium at a relative humidity (RH) of 60% and a temperature of 20 °C.

2.2 Fracture energy

The fracture energy, Gf, is defined as the energy needed to produce a unit area of traction-free crack and is measured in [J/m2]. It is the energy dissipated in the fracture process zone, from fracture initiation to creation of traction-free crack surfaces, i.e. when stresses can no longer be transferred between the two fracture surfaces (Gustafsson 2003). There are a number of methods to experimentally determine fracture properties of wood. For mode I (the opening mode), some commonly used methods include the use of compact tension specimens (CT), double cantilever beams (DCB) or single edge notched beams (SENB). In this study, SENB specimens subjected to three-point-bending were used to determine the fracture energy in mode I in tension perpendicular to the grain, according to the standard NT BUILD 422 (1993). The main reason for choosing this test method and the related evaluation methods was its simplicity. Using the approach stated in the standard, no assumptions about, for example, loading/unloading behaviour, bending/shear deformation of the specimen, the shape of the softening curve of the material, the tensile strength perpendicular to the grain, the size of the fracture process zone nor its development are necessary. Only the energy put into the system by the loading applied during the course of the test is evaluated. The most noticeable possible error involved herein is the influence of plastic dissipation at the loading point and at the supports, and plastic dissipation in the compression zone of the specimen. The influence of these sources of error is, however, expected to be negligible in relation to, for example, the variability of Gf between nominally equal specimens, and especially for small specimens like the ones used in the present study (Gustafsson 2003). The drawback when using the Nordtest method is that the information obtained is limited, i.e. only the fracture energy is evaluated. If additional parameters are of interest, for example, the shape of the softening curve of the material, including the strength of the material, more sophisticated (and complex) test and evaluation methods can be used. Such methods include, for example, the use of the so-called R-curve concept, and require additional assumptions regarding the fracture behaviour of the material (see e.g. de Moura et al. 2010; Dourado et al. 2011, 2015; Morel et al. 2005).

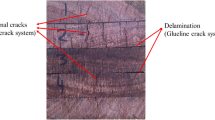

The fracture energy was determined for 16 unmodified and 16 modified sapwood specimens, as well as 12 unmodified and 11 modified heartwood specimens. Each specimen consisted of three wood pieces, glued together with polyvinyl acetate (PVAc), with geometry and material orientations defined according to Fig. 2a. The annual rings of the specimens were oriented aiming at a TL crack system, i.e. with the crack propagating in the longitudinal direction (fibre direction), L, and the normal to the fracture surface in the tangential direction, T. Due to variations in growth ring orientations, a pure TL crack system was difficult to achieve and the deviation was measured to be approximately 20–30° in the TR-plane, where R denotes the radial direction. The 10 mm deep notch parallel to the grain, illustrated in Fig. 2a, was cut right prior to the tests being conducted.

SENB specimen tested in three-point-bending in the fracture energy tests, where the specimen is composed of three wood pieces glued together. a Specimen geometry and material orientations, where L denotes the longitudinal direction, R the radial direction and T the tangential direction of the growth ring orientation. b Test set-up with supports visualised

The specimens were simply supported and loaded in three-point-bending, according to Fig. 2b. At one end, the specimens were placed on a steel prism resting on a steel ball and at the other on a steel prism resting on a steel cylinder, which in turn rested on ball bearings to reduce influence of friction. The span between the supports was 120 mm and the load, P, was applied at the midpoint, through a rounded cross head and a steel prism with a mass of mprism = 2.69 g. The load was applied with a material testing system, MTS 810, with displacement controlled movement of the cross head at a rate of 3 mm/min. All specimens were loaded until complete failure, recording load and mid-point displacement, the latter through the cross-head movement of the testing machine. The fracture energy was evaluated by the work done by the midpoint force and the dead weight of the specimen, divided by the fractured area, as indicated in the standard (NT BUILD 422 1993). Thus, the fracture energy perpendicular to the grain in mode I was evaluated as:

where mtot the weight of the specimen, mprism the weight of the steel prism placed under the applied midpoint force, u0 the displacement of the cross head at failure, Ac the fractured area and g the gravity acceleration. The work done by the midpoint force, W, was determined by numerical integration of the load–displacement response, using the trapezoidal method implemented in the software MATLAB.

2.3 Modulus of elasticity

The modulus of elasticity in compression parallel to the grain, EL, was determined for 16 modified and 16 unmodified samples consisting of sapwood. The geometry of each specimen was approximately 20 mm × 20 mm × 60 mm, in the radial, tangential and longitudinal directions, respectively, as illustrated in Fig. 3a.

The tests were conducted with a material testing system, MTS 810, and the specimens were loaded in the grain direction. On top of the specimen a steel cylinder was placed, with a steel ball placed in a centred cavity according to Fig. 3b. To reduce constraining shear forces, 3 layers of greased aluminium foil were placed in the interface between the specimen and the supports on both sides. The load, P, was applied with a displacement-controlled movement of the crosshead with a rate of 0.5 mm/min. The force was recorded by the testing machine, and the relative displacement by using two external extensometers, placed on opposite sides of the specimen as shown in Fig. 3. The initial distance between the extensometer pins mounted on the specimen was Linit = 12.5 mm.

The strain was determined based on an averaged value of the recorded relative displacements from the two extensometers and the initial length Linit. The stress in the longitudinal direction was evaluated by the applied force, P, divided by the cross-section area. In order to find a proper fit to recorded data, a regression line was fitted to test data corresponding to load values in the range 2 kN < P < 8 kN (corresponding to stress values of 5–20 MPa), according to the method of least squares. The slope of the regression line was used to estimate the modulus of elasticity parallel to the grain.

2.4 Tensile strength

The tensile strength perpendicular to the grain, ft,90, was determined for 5 unmodified and 6 modified samples consisting of sapwood. The geometry of each specimen was approximately 20 mm × 20 mm × 20 mm, in the radial, tangential and longitudinal directions respectively. A cylindrical notch with a radius of 5 mm was made, as illustrated in Fig. 4a. Prior to testing the specimens, they were glued with a cyanoacrylate adhesive to steel cylinders and stored at a RH of 60% and a temperature of 20 °C until the glue had cured. The cyanoacrylate adhesive was chosen based on pre-tests to find a suitable adhesive that would provide a combination of sufficient strength yet curing fast enough to simplify specimen handling.

The steel cylinders were connected to a material testing system, MTS 810, with hinged ends to allow mounting of the specimens without introducing any constraining forces prior to testing, see Fig. 4b. The specimens were loaded at a rate of 1 mm/min until complete failure and the applied tensile load was recorded by the testing machine. The tensile strength, ft,90, was evaluated by the maximum recorded load, Pmax, divided by the fractured area Ac.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Moisture content

Mean values and standard deviation of the moisture content (MC) for all examined test groups (USW; MSW; UHW; MHW) are presented in Table 1. The results clearly show a decreased moisture content for acetylated samples, which is an expected result (Rowell and Dickerson 2014). However, the measured moisture contents are slightly lower than values reported for acetylated Scots pine in previous studies (Epmeier and Kliger 2005). This is most probably attributed to a higher acetyl content of the samples investigated in this study, but it could also be a consequence of the examined samples being extremely dry prior to conditioning, or due to differences regarding acetylation techniques, climatic conditions and differences related to the origins of the material.

3.2 Fracture energy

All tests performed displayed a well-defined descending part of the load–displacement response, indicating a stable crack propagation. The work done by the midpoint force could thus be determined by numerical integration of the load–displacement response. In Fig. 5, typical load–displacement responses for unmodified and modified sapwood and heartwood are shown. Clear differences can be observed, for example, regarding the peak load, indicating a lowered fracture energy for the modified samples. Figure 6a illustrates a specimen under loading, as the crack propagates. In Fig. 6b, a typical fracture surface demonstrating a wavy pattern is shown, an attribute observed among all specimens.

Mean values and standard deviations for the fracture energy, Gf, and density, ρ, of corresponding specimens, are presented in Table 2. The difference in mean fracture energy between unmodified and modified sapwood, as well as heartwood, are presented in [J/m2] and [%]. Compared to unmodified samples, a decreased fracture energy was observed for the acetylated specimens. The mean values were 36% and 50% lower for acetylated heartwood and sapwood, respectively. The statistical significance of the difference is presented in the table through p-values and confidence intervals, according to a two-sample t-test, assuming unequal variances. There was an impact on the fracture energy at a level of significance greater than 99.9%. This observation clearly demonstrates an increased brittleness of acetylated Scots pine, which is in agreement with previous studies for another species (Reiterer and Sinn 2002). However, the observed impact appears larger in the current study. This could be due to differences in acetylation techniques, acetyl content, climatic conditions or species-specific effects (Scots pine versus spruce). It should also be emphasized that the acetylation process used in this study was optimised for radiata pine and not Scots pine.

In Fig. 7, the correlation between measured fracture energy and density are illustrated for each test group: USW; MSW; UHW; MHW. Data from all tested specimens are presented and within each plot equal markers indicate data from nominally equal specimens. A regression line is fitted to the data according to the method of least squares. A previous study conducted by Larsen and Gustafsson (1990) showed a positive correlation between the fracture energy and density for unmodified European softwoods. In the current study, the observed values of fracture energies for the unmodified specimens correspond well with the values reported by Larsen and Gustafsson (1990). In the present study, however, the correlation between the fracture energy and density was very low for same cases (R2 = 0.12, see Fig. 7a) and the corresponding trend lines indicated in Fig. 7 cannot be considered as being statistically significant. Hence, additional testing with a wider range of densities is recommended.

3.3 Modulus of elasticity

Results for the modulus of elasticity parallel to the grain, EL, and the density, ρ, of the corresponding samples are presented in Table 3. Mean values and standard deviations are stated, as well as the difference in mean modulus of elasticity between unmodified and modified sapwood. The statistical significance is presented by a p-value, according to a two-sample t-test with unequal variances, and a confidence interval with a significance level of 95%. Based on the statistical data, no significant impact on the modulus of elasticity could be concluded for specimens conditioned at the specified relative humidity and temperature.

The correlation between the modulus of elasticity and the density is presented in Fig. 8. The results are presented separately for unmodified and modified sapwood, and within each plot equal markers represent nominally equal specimens. The results suggest a positive correlation, i.e. an increasing modulus of elasticity for an increased density, which is expected (Kollmann 1968). However, as previously stated, statistically significant observations regarding the correlation would require results from a wider range of densities and further testing is recommended.

3.4 Tensile strength

Mean values and standard deviation for the tensile strength, ft,90, and the density, ρ, of the corresponding samples are presented in Table 4 and an example of a typical failure surface is shown in Fig. 9. The difference in mean tensile strength between unmodified and modified sapwood is presented in [MPa] and [%]. The statistical significance is defined by a p-value, according to a two-sample t-test with unequal variances, and a confidence interval with a significance level of 95%. Based on the result, no significant differences could be concluded regarding the tensile strength between unmodified and modified samples. However, for the tensile strength, it should be emphasised that these results only provide an indication of the effect of acetylation due to the limited number of samples.

In Fig. 10, the correlation between the tensile strength and the density is shown for unmodified and modified samples consisting of sapwood. Data from all tested specimens are presented, and within each plot, equal markers indicate data from nominally equal specimens. As for the fracture energy and the modulus of elasticity, conclusions regarding the correlation of the tensile strength to the density would require examination of a wider range of densities. Thus, further testing is recommended.

3.5 Discussion

As previously mentioned, the impact of chemical modification on mechanical properties can be considered to be a consequence of changed physical properties, caused by changing the chemistry of the cell wall polymers. As stated by Bongers and Beckers (2003) as well as Larsson and Simonson (1994), changes in the mechanical properties of modified wood can be regarded as a compilation of positive effects, gained by the lower moisture content, and negative effects, impaired by having less fibres per cross-section area. For unmodified wood, a lower moisture content correlates to increased strength and stiffness (Kollmann 1968). Based on the results of the current study, no influence of acetylation on the strength nor the stiffness can be concluded. However, it should be emphasised that the current study considers samples conditioned at equal climates. Due to differences in hygroscopicity between unmodified and acetylated samples, a specific climate will result in different EMC for modified and unmodified wood. The mean moisture content for unmodified specimens was found to be 10.3–10.4%, while it was 2.5–3.5% for modified samples. Due to the strong correlation between the moisture content and the strength and stiffness for unmodified wood, the results and conclusions in this study might have been different if samples had been compared after conditioning at different climates yielding the same EMC.

In contrast to increased stiffness and strength for a decreased moisture content, studies have demonstrated that a low moisture content correlates to a decreased fracture energy (Phan et al. 2017; Reiterer and Tschegg 2002; Vasic & Stanzl-Tschegg 2007). In the current study, a significant decrease in the fracture energy was observed for the acetylated samples. To investigate why acetylation impairs the fracture energy, additional research is required. This could for instance include studies of the correlation between the fracture energy and the moisture content for modified and unmodified samples. Findings from such a study could provide an indication of whether the decreased fracture energy is merely a consequence of a drier, hence more brittle, material. Yet, considering the use of acetylated wood in structural elements, it is still of a practical importance to compare samples subjected to equal climatic conditions, i.e. temperature and relative humidity. Similarly, this study examined samples of equal dimensions. The lower fracture energy could also be an adverse effect, caused by having less fibres per cross section area. Nevertheless, for engineering practice and in design applications, the current comparison is valid since structural design is based on nominal (gross) dimensions.

Another possible explanation for the decreased fracture energy, could be degradation of the cell wall polymers. During the acetylation process the material is subjected to elevated temperatures (approximately 120–130 ºC) at drying prior to acetylation, in the reaction with acetic anhydride as well as during the removal of the by-product acetic acid. Previous studies on thermally modified wood have indicated a significant decrease in the fracture energy (Majano-Majano et al. 2012; Reiterer and Sinn 2002). Although temperatures applied in chemical modification methods are not as high as in thermal modification methods, the cell wall polymers may still be affected. Moreover, as stated by Bongers and van Zetten (2017) and Bongers and Uphill (2019), time, temperature and pressure are key parameters to attain a consistent and uniform treatment in the process of acetylation. It is important to base these parameters on a deep knowledge of the specific wood species. Otherwise, the acetylation process might lack in uniformity, resulting in an uneven distribution of acetyl groups, and might cause internal stresses, possibly resulting in the formation of cracks. As the examined material was treated with an acetylation process optimised for radiata pine and not Scots pine, it would be of interest to examine the microstructure of the wood prior to testing, to analyse the occurrence of already existing micro-cracks that might have affected the outcome of the study.

To enable the use of acetylated young Scots pine in outdoor load-bearing applications, the increased brittleness has to be regarded in the design of mechanical joints and in structures where tensile stresses perpendicular to grain appear. The fracture energy is, for example, important for the load-bearing capacity of joints, subjected to a load at an angle to the fibre direction, and when determining edge distances to avoid brittle failure modes. Some design formulae in Eurocode 5 are based on fracture mechanics, but include assumptions regarding fracture characteristics, determined through empirical testing. Further studies are needed to determine if current design codes have to be revised, to account for the increased brittleness of modified wood.

4 Conclusion

In this study, unmodified and modified samples of Scots pine were examined. Modified samples had an acetyl content of approximately 20%, and all specimens were conditioned until equilibrium at a RH of 60% and a temperature of 20 °C. Acetylated samples demonstrated a significantly lower moisture content than unmodified samples. Significant differences were also observed regarding the fracture energy, where the mean value decreased with 36% and 50% for acetylated heartwood and sapwood, respectively. No significant effects of the acetylation regarding tensile strength perpendicular to the grain, nor modulus of elasticity parallel to the grain, could be concluded. The observations demonstrate an increased brittleness for acetylated Scots pine. This fact is important to regard in the design of mechanical joints as well as in structural elements where tensile stresses perpendicular to grain appear. Based on the knowledge gained, further studies will be conducted regarding structural applications to determine whether current design codes have to be revised, in order to account for the increased brittleness of acetylated Scots pine.

To further investigate the cause of the decreased fracture energy, both modified and unmodified specimens conditioned at a range of moisture contents should be examined. By doing so, the effect of MC on the fracture energy can be separated from other effects, such as the changed chemistry and the amount of wood fibres. Furthermore, it would be of interest to investigate the microstructure of the modified wood, to study the presence of micro-cracks and determine whether there is a degradation of the cell wall polymers.

References

Bongers F, Beckers E (2003) Mechanical properties of acetylated solid wood treated on pilot plant scale. In: Proceedings of the first european conference on wood modification, Ghent, Belgium

Bongers F, Uphill SJ (2019) The potential of wood acetylation. In: 7th-international scientific conference on hardwood processing. Delft, The Netherlands

Bongers F, van Zetten J (2017) Consistency of performance of acetylated wood. The international research group on wood protection, IRG-WP 17- 20608

Brelid PL (2013) Benchmarking and state of the art for modified wood. SP Technical Research Institute of Sweden, Stockholm

Cabrero JM, Honfi D, Jockwer R, Yurrita M (2019) A probabilistic study of brittle failure in dowel-type timber connections with steel plates loaded parallel to the grain. Wood Mat Sci Eng 14(5):298–311

Dourado N, de Moura MSFS, Morais J (2011) A numerical study on the SEN-TPB test applied to mode I wood fracture characterization. Int J Solids Struct 48(2):234–242

Dourado N, de Moura MSFS, Morel S, Morais J (2015) Wood fracture characterization under mode I loading using the three-point-bending test. Experimental investigation of Picea abies L. Int J Fract 194:1–9

Dreher WA, Goldstein IS, Cramer GR (1964) Mechanical properties of acetylated wood. Forest Products Journal 14:66–68

Ehlbeck J, Görlacher R (2017) E11 Joints loaded perpendicular to the grain. In: Blass HJ, Sandhaas C (eds) Timber engineering—principles for design. KIT Scientific Publishing, Karlsruhe, pp 441–457

Epmeier H, Kliger R (2005) Experimental study of material properties of modified Scots pine. Holz Roh- Werkst 63:430–436

Fuchs W (1928) Genuine lignin. I. Acetylation of pine wood. Ber Dtsch Chem Ges 61:948–951

Giotra K (2014) Process for wood acetylation and product thereof, European Patent No. 2818287A1. European Patent Office

Goldstein IS, Jeroski EB, Nielson JF, Weaver JW (1961) Acetylation of wood in lumber thickness. Forest Products J 11:363–370

Gustafsson PJ (2003) Fracture perpendicular to grain—structural applications. In: Thelandersson S, Larsen HJ (eds) Timber engineering. Wiley, Chichester, pp 114–115

Jensen JL, Quenneville P (2011) Experimental investigations on row shear and splitting in bolted connections. Constr Build Mater 25(5):2420–2425

Kollmann FFP (1968) Mechanics and rheology of wood. In: Kollmann FFP, Côté WA (eds) Principles of wood science and technology. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, pp 292–419

Larsen HJ, Gustafsson PJ (1990) The fracture energy of wood in tension perpendicular to the grain: results from a joint testing project. In: International council for research and innovation in building and construction, working commission CIB-W18A, proceedings Meeting 23, Paper CIB-W18A/23–19–2, Lisbon, Portugal

Larsson P, Simonson R (1994) A study of strength, hardness and deformation of acetylated Scandinavian softwoods. Holz Roh- Werkst 52:83–86

Majano-Majano A, Hughes M, Fernandez-Cabo JL (2012) The fracture toughness and properties of thermally modified beech and ash at different moisture contents. Wood Sci Technol 46:5–21

Morel S, Dourado N, Valentin G, Morais J (2005) Wood: a quasibrittle material R-curve behavior and peak load evaluation. Int J Fract 131(4):385–400

de Moura MSFS, Dourado N, Morais J (2010) Crack equivalent based method applied to wood fracture characterization using the single edge notched-three point bending test. Eng Fract Mech 77(3):510–520

NT BUILD 422 (1993) Wood: Fracture energy in tension perpendicular to the grain. Nordtest Method 11/1993

Phan NA, Chaplain M, Morel S, Coureau JL (2017) Influence of moisture content on mode I fracture process of Pinus pinaster: evolution of micro-cracking and crack-bridging energies highlighted by bilinear softening in cohesive zone model. Wood Sci Technol 51(5):1051–1066

Reiterer A, Sinn G (2002) Fracture behaviour of modified spruce wood: a study using linear and non linear fracture mechanics. Holzforschung 56:191–198

Reiterer A, Tschegg S (2002) The influence of moisture content on the mode I fracture behaviour of sprucewood. J Mater Sci 37(20):4487–4491

Rowell RM (1983) Chemical Modification of Wood. Forest Products Abstracts 6(12):363–382

Rowell RM (1996) Physical and mechanical properties of chemically modified wood. Chem Modification Lignocellulosic Materials 1:295–310

Rowell RM (2006) Chemical modification of wood: a short review. Wood Mat Sci Eng 1:29–33

Rowell RM, Dickerson JP (2014) Acetylation of wood. In: Schultz TP, Goodell B, Nicholas DD (eds) Deterioration and protection of sustainable biomaterials. American Chemical Society, Washington, pp 301–327

Schwanninger M, Stefke B, Hinterstoisser B (2011) Qualitative assessment of acetylated wood with infrared spectroscopic methods. J Near Infrared Spectrosc 19(5):349–357

Sjödin J, Serrano E (2008) A numerical study of methods to predict the capacity of multiple steel-timber dowel joints. Holz Roh- Werkst 66:447–454

Vasic S, Stanzl-Tschegg S (2007) Experimental and numerical investigation of wood fracture mechanisms at different humidity levels. Holzforschung 61(4):367–374

Acknowledgements

Open access funding provided by Lund University. This research was made possible thanks to financial support from the research council Formas (grant number 2016–01138) and from the strategic innovation programme BioInnovation, through the project “Outdoor Load-bearing Timber Structures” (grant number 2017–02712). BioInnovation is funded by the innovation agency Vinnova, by the Swedish Energy Agency and by Formas. The financial support from these organisations and the support from all project partners is hereby gratefully acknowledged.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Forsman, K., Serrano, E., Danielsson, H. et al. Fracture characteristics of acetylated young Scots pine. Eur. J. Wood Prod. 78, 693–703 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00107-020-01548-3

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00107-020-01548-3