Abstract

Background

Monacolin J (MJ) is a key intermediate for the synthesis of cholesterol-lowering drug simvastatin. Current industrial production of MJ involves complicated chemical hydrolysis of microbial fermented lovastatin. Recently, heterologous production of MJ has been achieved in yeast and bacteria, but the resulting metabolic stress and excessive accumulation of the compound adversely affect cell activity.

Results

Five genes, tapA, stapA, slovI, smokI and smlcE, coding for fungal statin pump proteins were expressed in an MJ producing yeast strain, Komagataella phaffii J#9. Overexpression of these genes facilitated MJ production. Among them, tapA from Aspergillus terreus highly improved MJ production and led to a titer increase of 108%. Exogenous MJ feeding study on an MJ non-producing strain GS-PGAP-TapA was then performed, and the results illustrated tough entry of MJ into cells and possible efflux action of TapA. Further, intracellular and extracellular MJ levels of J#9 and J#9-TapA were analyzed. The extracellular MJ level of J#9-TapA increased faster, but its intracellular MJ percentage kept lower as compared to J#9. The results proved that TapA effectively excreted MJ from cells. Then functions of TapA were evaluated in a high-production bioreactor fermentation. Differently, TapA expression caused a low MJ titer but high intracellular MJ accumulation in J#9-TapA compared with J#9.

Conclusions

Statin pump proteins improved MJ production in K. phaffii in a shake flask. Exogenous MJ feeding and endogenous MJ producing experiments demonstrated the efflux function of TapA. TapA improved MJ production at low MJ levels in a shake flask, but decreased it at high MJ levels in a bioreactor. This finding is useful for statin pump improvement and metabolic engineering for statin bioproduction.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cardiovascular disease (CVD), as a type of disease with mortality exceeding cancer (Benjamin et al. 2018), has attracted much attention in recent years. It is estimated that by the year 2030, more than 23.6 million people will die from CVD annually (Balakumar et al. 2016). As is known, statins can be used to treat CVD and lipid disorders (Askarizadeh et al. 2019). Lovastatin (LV) is a natural cholesterol-lowering drug which can significantly reduce low density lipoprotein (Alberts et al. 1980). Its derived semi-synthesis drug, simvastatin (SV), even shows higher medicinal and economic value and less side effects (Barrios-Gonzalez and Miranda 2010). Both LV and SV function as highly competitive hydroxymethylglutaryl coenzyme A (HMG-CoA) reductase inhibitors.

Chemical synthesis of SV requires a key intermediate of monacolin J (MJ). Currently, industrial production of MJ is realized through hydrolysis of LV with large amounts of concentrated alkali, acids, and organic reagents (Jaeheon et al. 2005); while industrial production of LV is usually implemented by large-scale fermentation of Aspergillus terreus strains (Liu et al. 2018a). This manufacturing process faces serious problems such as various byproducts, complex process, high requirements for operators, and costly wastewater treatment (Liu et al. 2018a). With the development of synthetic biology, heterologous productions of MJ have been achieved in yeast cells recently (Xie and Tang 2007; Gao et al. 2010; Xu et al. 2013; Liu et al. 2018a, b; Bond and Tang 2019). Nevertheless, heterologous expression of various genes might bring metabolic stress on the expression hosts and accumulation of target products might cause toxicity to the chassis cells (Alper et al. 2006; Wang et al. 2017). Product toxicity is a common problem in engineered strains producing either proteins or small molecule compounds. Therefore, it is necessary to balance production and survival when modifying strains (Alper et al. 2006; Wang et al. 2017).

In comparison to heterologous host, the native microorganism usually owns self-protection function that can release certain metabolites. For instance, secondary metabolic gene cluster commonly contains a gene coding for a transporter protein. It can excrete specific compounds from the cell, thereby establishing a self-resistance mechanism (Martín et al. 2005). Efflux pumps are a type of membrane transporter proteins that can export toxins from cells by proton-motive force (Nikaido and Takatsuka 2009). Thus, efflux pumps may release metabolic burden in heterologous host. Till now, transportation functions of putative statin efflux pumps from statin-producing fungi have not been well verified. In a previous study, Ley et al. (2015) identified an efflux pump protein of MlcE from Penicillium citrinum. The MlcE-overexpressing yeast strains then showed obvious resistance to mevastatin (MV), LV and SV (Ley et al. 2015). However, since the statin biosynthetic pathway was not assembled in their work, it was not possible to analyze if this pump protein could promote the synthesis of statins. Also, heterologous expression of a homolog of MlcE did not trigger increased resistance to LV in a LV-sensitive strain Aspergillus nidulans (Hutchinson et al. 2000). Differently, our previous work revealed that a homolog (TapA) of MlcE from A. terreus promoted LV release and improved LV production by a methanol-utilizing yeast Komagataella phaffii (syn Pichia pastoris) (Liu et al. 2018a).

Assembly of MJ biosynthetic pathway and intracellular accumulation of products in K. phaffii adversely affected cell growth (Liu et al. 2018b). As MJ owns similar nucleus structure to LV, TapA may also improve the efflux of intracellular MJ. Our previous data indicated that MJ had a limited ability to cross cellular membranes of K. phaffii (Liu et al. 2018b), thus overexpression of TapA might also improve MJ production by K. phaffii, which provides the intermediate directly for the semi-synthesis of SV. With this in mind, we then tested TapA and other putative statin pump proteins from different species and analyzed their efflux functions to MJ. This study provides reference to statin efflux control for release of intracellular statin molecules, which may facilitate statin production in either heterologous or homologous hosts.

Materials and methods

Construction of plasmids and strains

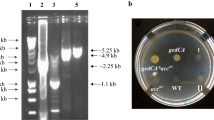

Oligonucleotides are synthesized by Suzhou Genewiz Biotech Co., Ltd. (China) and listed in Additional file 1: Table S1. Yeast expression vectors of pPICZ B, pAG32 and pZ_PGAP-tapA were stored in our laboratory (Liu et al. 2018a, b). Escherichia coli (E. coli) Top10 was purchased from Takara and used for plasmid construction. K. phaffii GS115 was purchased from Invitrogen and used for construction of expression strains. J#9 and GS-PGAP-TapA strains were constructed and stored in our laboratory (Liu et al. 2018a). The linearized vector was assembled with different fragments by ClonExpress™ II One Step Cloning Kit (Vazyme Biotech Co., Ltd., China), generating various target plasmids. The pAGA plasmid (Additional file 1: Figure S1) was constructed by inserting PAOX1-TT fragment into the pAG32 vector (Liu et al. 2018b). The PAOX1-TT fragment was amplified from the pPICZ B vector. The tapA gene was amplified from pZ_PGAP-tapA (Liu et al. 2018a). The cDNA of tapA, lovI, mokI and mlcE were codon optimized and synthesized. Plasmids of pG_TapA, pG_sTapA, pG_sLovI, pG_sMokI and pG_sMlcE (Additional file 1: Figure S1) were generated by inserting expression cassettes of tapA and other four codon-optimized genes into pAGA, respectively, under control of the AOX1 promoter (PAOX1). They were linearized by PmeI and transformed into K. phaffii J#9 by electroporation, and positive transformants of J#9-TapA, J#9-sTapA, J#9-sLovI, J#9-sMokI and J#9-sMlcE were screened by hygromycin B (750 μg/mL). Genotypes of all strains were verified by PCR analysis. Plasmids and strains used in this study are listed in Table 1.

Culture media and conditions

Escherichia coli strains were cultivated at 37 °C and 200 r/min in LLB medium [1% (w/v) tryptone, 0.5% (w/v) yeast extract, 0.5% (w/v) NaCl]. The yeast strains were cultured at 30 °C and 200 r/min in YPD [2% (w/v) tryptone, 1% (w/v) yeast extract, 2% (w/v) glucose] or YNM medium [1.34% (w/v) yeast nitrogen base without amino acids, 1% (w/v) methanol]. A phosphate buffer [0.16% (w/v) KOH, 0.68% (w/v) KH2PO4] was added to stabilize pH levels. For YNM medium, histidine (0.02 g/L) was supplemented for cell growth. Ampicillin and hygromycin B were used for screening of E. coli and K. phaffii transformants, respectively. For agar plate culture, agar powder was added in liquid medium at a concentration of 2% (w/v) before sterilization. Media were sterilized at 121 °C for 20 min. Glucose solution was filter-sterilized before use. Methanol or glucose was separately added into medium.

Susceptibility analysis of MJ

The MJ purity was prepared by a preparative high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC). The obtained MJ (723 mg) was dissolved in 10 ml anhydrous methanol, preheated to 50 °C, alkalinized by 5 mL of 0.6 mol/L NaOH and incubated at 50 °C for 2 h. Then the pH was adjusted to 7.2 with 0.4 mol/L HCl, and made up to 20 ml with double distilled water. The active sample (100 mmol/L) was sterilized by filtration and stored at − 20 °C for use.

For susceptibility analysis, strains were grown in YPD medium to an optical density (OD600) of 4.0–6.0. Cells were then inoculated into YPD medium (OD600 ≈ 1.0) containing 0, 0.3, 0.6, or 2.3 mmol/L MJ, respectively. The culture broth was fed with 2 mL glucose solution [50% (w/v)] every 24 h. For cell growth analysis, 1 mL culture broth was collected every 12 h and centrifuged at 12,000g for 3 min. The obtained cells were washed with sterile water, centrifuged (12,000g) and supernatant removed, and then dried at 70 °C to constant dry cell weight (DCW). Generally, cell broth with OD600 of 1.0 was equivalent to about 0.2 g/L DCW for all the tested strains. Broth sample (5 mL) was collected at 24-h intervals to measure MJ concentrations inside and outside the cells. Statistical analysis was performed on three replicates and each experiment was conducted at least twice.

Fermentation in shake flask and bioreactor

For shake flask culture, 150 μL yeast storage (− 80 °C) was inoculated into 5 mL YPD medium in a 30-mL serum bottle, and grown at 30 °C and 200 r/min for 3–4 days. Afterwards, 100 μL cell broth was added into 50 mL YPD medium in a 250-mL shake flask and cultured overnight (30 °C and 200 r/min). It was then inoculated into YPD medium by 0.1% (v/v) and grown overnight (30 °C and 200 r/min) to OD600 of 4.0–6.0. A calculated amount of culture broth was then centrifuged at 4 °C and 6000g for 10 min to harvest cells. The cells were washed by YNB medium and centrifuged for two rounds, and then resuspended in YNB medium. The seeds were inoculated into YNM medium to a final OD600 of 1.0 for cultivation. Methanol was fed at 1% (v/v) every 24 h. Broth samples (5 mL) were collected at 24-h intervals for analysis of cell growth and metabolite production. Bioreactor fermentation was performed as described previously (Liu et al. 2018a). Broth samples (2 mL) were collected at 8-h intervals and analyzed twice to measure the cell growth and concentrations of the metabolites.

Extraction and quantification of MJ

Yeast cells were obtained by centrifugation (4 °C, 6000g) and washed with sterile water. Then cells were resuspended in 1 ml acetone and incubated at 50 °C for 2 h. The intracellular extracts were obtained by centrifugation of the acetone mixture at 12,000g for 3 min. Fermentation broth (for total extracts) or the obtained supernatant (for extracellular extracts) was extracted by ethyl acetate as described previously (Liu et al. 2018a). Then all extracts were analyzed by HPLC (Liu et al. 2018a). The chromatogram examples of MJ standard and experimental samples were shown in Additional file 1: Figure S2.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed on three replicates and each experiment was conducted at least twice. The independent-sample t test was performed to determine the differences among grouped data. Statistical significance was assessed at P < 0.05.

Results and discussion

MJ production with statin pump proteins from different species

Previously, assembly of MJ biosynthetic pathway in K. phaffii showed an adverse effect on cell growth (Liu et al. 2018b). Pumping intracellular MJ out of the cells through an efflux protein may relieve metabolic stress and further improve MJ production. A BLAST search with MlcE from Penicillium citrinum (Ley et al. 2015) hit a series of homologs (Additional file 1: Table S2). Phylogenetic analysis of these proteins indicated three homologs closely related with MlcE, i.e., TapA from A. terreus NIH2624, LovI from A. terreus ATCC20542 and MokI from Monascus pilosus BCRC38072 (Fig. 1). Among them, TapA has been identified to efflux intracellular LV (Liu et al. 2018b). Amino acid (aa) sequence of each protein was then aligned to infer their conserved functional domains. The tapA, lovI and mokI are from LV gene clusters and their coding proteins showed a highly conserved N-terminus region (Additional file 1: Figure S3). Differently, mlcE is from mevastatin (MV) gene cluster, and its coding protein showed a relatively low homology with others.

Phylogenetic analysis of MlcE homologs from various strains. The evolutionary tree was inferred by MEGA7 using the Neighbor-Joining method (Saitou and Nei 1987). Values indicated the number of times (in percentages) that each branch topology was found in 1000 replicates of a bootstrap analysis. The evolutionary distances were computed using the Poisson correction method (Zuckerkandl and Pauling 1965) and are in the units of the number of amino acid substitutions per site. Information of strains and proteins were listed in Additional file 1: Table S2

To test their functions, codon-optimized genes, i.e., stapA, slovI, smokI and smlcE, were fully synthesized for expression in K. phaffii. Then genes were overexpressed in a previously constructed MJ-producing strain, K. phaffii J#9 (Liu et al. 2018a). Strains with single-copy gene were identified and designated as J#9-TapA, J#9-sTapA, J#9-sMlcE, J#9-sLovI and J#9-sMokI, respectively. Each strain was cultured in YNM medium using J#9 as a control. As shown in Fig. 2a, J#9-TapA produced 0.14 mmol/L (50.3 mg/L) of total MJ at 96 h, which was 108% higher than that of J#9 (P < 0.05). Also, overexpression of stapA, slovI, smokI and smlcE all improved MJ production as compared to the control (P < 0.05). The MJ productivity showed the similar tendency to the titer (Fig. 2b). The results indicated that these proteins probably functioned as efflux pumps. Nevertheless, the titer and productivity of J#9-sTapA were lower than that of J#9-TapA. Various transformants from both constructions showed the same results (data not shown) and the reason still kept unknown. The MJ productions of J#9-sLovI, J#9-sMokI and J#9-sMlcE were comparable to that of J#9-TapA, thus we then used TapA for the following study.

Expression of statin pump proteins improved MJ production. a MJ titer of strains expressing various statin pump proteins. b MJ productivity of strains expressing various statin pump proteins. Cells were cultured in YNM medium at an initial OD600 of 1.0. Then 0.5% (w/v) methanol was fed every 24 h. Titers were measured in triplicate and experiments were performed three times. Statistical significance of MJ titer of each statin pump protein expression strain relative to J#9 was analyzed for each time point. *P < 0.05 at 24 h, #P < 0.05 at 48 h, ×P < 0.05 at 72 h, ⁜P < 0.05 at 96 h and n.s. not significant

Efflux function analysis of TapA by exogenous MJ feeding and endogenous MJ synthesis

Although overexpression of TapA improved MJ production, there was no direct evidence for its efflux function. Also, it is undetermined that whether TapA could transfer MJ into cells. Thus, MJ feeding experiments were performed. A GS-PGAP-TapA strain was constructed firstly, for which tapA was expressed as single-copy under the control of the constitutive promoter PGAP in wild-type K. phaffii GS115. It was then cultured in liquid YPD medium supplemented with increasing concentrations of MJ in shake flask using GS115 as a control. The results showed that cell growth was significantly affected by MJ feeding. With increase of MJ concentration, cell growth of GS-PGAP-TapA and GS115 gradually decreased (Fig. 3a-c). For all cases, the vast majority of the added MJ kept outside of the cells (Fig. 3d–f), and generally, no more than 2% of MJ could enter the cells. These data further supported the fact of the limited intracellular entry of MJ. Still, the intracellular MJ level of GS-PGAP-TapA kept lower than that of the wild-type for MJ feeding of 2.3 mmol/L (Fig. 3f). The result initially illustrated the efflux function of TapA on MJ.

TapA function analysis by MJ distribution of various constructed strains. Dry cell weight of GS-PGAP-TapA and wild-type GS115 fed with MJ of 0.3 mmol/L (a), 0.6 mmol/L (b) and 2.3 mmol/L (c) in shake flask. Extracellular and intracellular MJ levels of GS-PGAP-TapA and GS115 fed with MJ of 0.3 mmol/L (d), 0.6 mmol/L (e) and 2.3 mmol/L (f) in shake flask. Dry cell weight (g), extracellular and intracellular MJ (h) and intracellular MJ percentage (i) of J#9-TapA and J#9 in shake flask. Three replicates were tested and experiments were conducted three times. Statistical significance was analyzed for each comparative group at various time points. *P < 0.05 for cell growth of GS115 relative to GS115 with MJ feeding. #P < 0.05 for cell growth of GS-PGAP-TapA relative to GS-PGAP-TapA with MJ feeding. ×P < 0.05 for intracellular MJ of GS115 relative to that of GS-PGAP-TapA. ⁜P < 0.05 for extracellular MJ of J#9 relative to that of J#9-TapA. †P < 0.05 for intracellular percentage of MJ of J#9 relative to that of J#9-TapA. Data with not significant differences were not marked in figure. Error bars smaller than the plot symbols were not displayed by the GraphPad software

To further clarify the function of TapA, we analyzed MJ distribution in J#9 and J#9-TapA strains, which can produce MJ in shake flask. Cell growth of J#9-TapA and J#9 showed no significant difference (Fig. 3g). The intracellular MJ concentrations of J#9 and J#9-TapA were close, while the extracellular MJ level of J#9-TapA was obviously higher than that of J#9 during 48–96 h. Also, the extracellular MJ level of J#9-TapA increased faster than that of J#9 (Additional file 1: Fig. S4). Moreover, for both strains the intracellular MJ percentage kept decreasing along with the increasing total MJ production during the whole culture phase. The intracellular MJ percentage of J#9-TapA always kept lower than that of J#9 (Fig. 3i). These results proved that overexpression of TapA effectively pumped MJ out of the cells.

Evaluation of TapA function and MJ production in bioreactor fermentation

Scale-up experiments were performed to further investigate the function of TapA and MJ production in a 5-L stirred tank bioreactor. Culture medium and conditions were the same for the strains of J#9 and J#9-TapA. As shown in Fig. 4a, the highest MJ titer reached 2.71 mmol/L (975.5 mg/L) for J#9. However, it only reached 1.83 mmol/L (657.8 mg/L) for J#9-TapA, which was 33% lower than that of J#9. In addition, the MJ specific productivity of J#9-TapA was also lower than that of J#9 during the late phase. Thus, overexpression of TapA actually decreased the production of MJ in bioreactor, which was absolutely different from the results observed in shake flask. However, cell growth of the two strains showed similar tendency despite that higher cell densities were obtained in bioreactor compared with that in shake flask (Figs. 3a, 4a). After methanol induction, MJ titer curves almost overlapped before 52 h for the two strains in bioreactor. Also, MJ specific productivity curves of the two strains nearly overlapped before 48 h. These results indicated that TapA should not affect expression of biosynthetic genes. In contrast, both titer curves and specific productivity curves differed a lot thereafter. It implied that a great metabolic variation could take place, hence intracellular and extracellular distribution of MJ were then analyzed (Fig. 4b). During the whole fermentation process of J#9, intracellular MJ content maintained at a nearly constant level (lower than 16%), while extracellular MJ level kept increasing after induction until 60 h and then decreased. In contrast, MJ content inside and outside the cells of J#9-TapA showed synchronous trends of increase in early phase but followed by a quick decrease (Fig. 4c). Notably, intracellular MJ percentage of J#9-TapA dramatically increased from 15 to 50% during the culture period of 36–52 h. This tendency differed a lot in comparison with that in shake flask (Fig. 3h, i).

Evaluation of TapA function and MJ production of J#9-TapA and J#9 in bioreactor. a Time profiles of J#9-TapA and J#9 fermentation in a 5-L stirred tank bioreactor. Broth samples (2 mL) were collected at 8-h intervals and were analyzed twice to quantify cell growth and MJ concentration. Culture methods kept the same for both strains. Extracellular MJ level, intracellular MJ level and intracellular MJ percentage in strains of J#9 (b) and J#9-TapA (c). The bioreactor fermentation experiments were conducted two times

Considering the above-mentioned results, we proposed a possible mechanism by which TapA acted on the substrate of MJ. We inferred that TapA probably owns both export and import functions on the substrate of MJ despite that we have no suitable means to prove its import ability. Moreover, its export capacity could far exceed import capacity. At a low intracellular MJ level, TapA efficiently promoted the transport of intracellular MJ out of the cells, allowing continuous synthesis of MJ and increasing MJ production. However, when extracellular MJ accumulated to a high level, it will somehow improve MJ crossing into the cells (Fig. 3d–f). For MJ feeding experiments, GS-PGAP-TapA was not able to produce MJ, and meanwhile, MJ export was stronger than import, so it would not lead to high MJ accumulation inside the cells (Fig. 3d–f). But for MJ producing experiments, J#9-TapA showed good MJ producing capacity (Figs. 2, 4a). The produced MJ plus the imported MJ by TapA could surpass the export capacity of TapA. Therefore, intracellular MJ severely accumulated which further affected cell activity and MJ biosynthesis (Fig. 4a, c), while for J#9, as it lacks TapA-mediated MJ import, its intracellular MJ accumulation was not as serious as that in J#9-TapA (Fig. 4b). This allowed otherwise a higher MJ production compared with the TapA expressing strain (Fig. 4a).

MJ is an important intermediate for both natural biosynthesis of LV and the semi-synthesis of SV. The rapid development of synthetic biology allows heterologous synthesis of MJ in yeast cells, which was further converted to SV by broken yeast cells (Bond and Tang, 2019) or E. coli whole cells (Xie and Tang, 2007). This study finds that TapA expression can increase the intracellular accumulation of MJ in yeast for the high-level production in bioreactor. Although the total MJ production decreased, the accumulated MJ inside the cells may facilitate biosynthesis of its downstream products. For instance, TapA expression indeed improved LV production by K. phaffii in bioreactor (Liu et al. 2018a). On the other hand, SV has higher medicinal and economic value than LV (Barrios-Gonzalez and Miranda 2010), thus production of MJ is still preferred to provide the direct intermediate for SV synthesis. To the present, the crystal structure of statin pump protein is still unknown. Clarifying the binding behaviors between protein and substrate may further explain the findings in this work. Also, directed evolution efforts on TapA may ameliorate its functions, such as reduction of its import capacity at high MJ level. Besides, although some yeast native transporters were identified to increase drug resistance (do Valle Matta et al. 2001), it has been seldom reported that heterologous pump proteins are expressed and function in yeast hosts. The identified functions of MlcE (Ley et al. 2015) and TapA (Liu et al. 2018a and this work) indicated that introducing pump proteins into heterologous drug production hosts could be an alternative strategy to increase final product titers.

Conclusions

Statin pump proteins from different species efficiently enhanced MJ production in K. phaffii. Exogenous MJ feeding and endogenous MJ producing tests demonstrated the efflux function of the pump protein TapA. TapA highly improved MJ production at low MJ levels, but decreased MJ output at high MJ levels, which was closely related with its export function and possible import action. This finding is useful for statin pump protein modification and metabolic engineering for statin bioproduction.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated during this study are included in this article.

Abbreviations

- K. phaffii :

-

Komagataella phaffii

- P. pastoris :

-

Pichia pastoris

- A. terreus :

-

Aspergillus terreus

- E. coli :

-

Escherichia coli

- MJ:

-

Monacolin J

- LV:

-

Lovastatin

- SV:

-

Simvastatin

- MV:

-

Mevastatin

References

Alberts AW, Chen J, Kuron G, Hunt V, Huff J, Hoffman C, Rothrock J, Lopez M, Joshua H, Harris E, Patchett A, Monaghan R, Currie S, Stapley E, Albers-schonberg G, Hensens O, Hirshfield J, Hoogsteen K, Liesch J, Springer J (1980) Mevinolin: a highly potent competitive inhibitor of hydroxymethylglutaryl-coenzyme A reductase and a cholesterol-lowering agent. Biochemistry 77:3957–3961

Alper H, Moxley J, Nevoigt E, Fink GR, Stephanopoulos G (2006) Engineering yeast transcription machinery for improved ethanol tolerance and production. Science 314:1565–1568

Askarizadeh A, Butler AE, Badiee A, Sahebkar A (2019) Liposomal nanocarriers for statins: a pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamics appraisal. J Cell Physiol 234:1219–1229

Balakumar P, Maung-U K, Jagadeesh G (2016) Prevalence and prevention of cardiovascular disease and diabetes mellitus. Pharma Res 113:600–609

Barrios-Gonzalez J, Miranda RU (2010) Biotechnological production and applications of statins. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 85:869–883

Benjamin EJ, Virani SS, Callaway CW, Chang AR, Cheng S, Chiuve SE, Cushman M et al (2018) Heart disease and stroke statistics-2018 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation 137:e67–e492

Bond CM, Tang Y (2019) Engineering Saccharomyces cerevisiae for production of simvastatin. Metab Eng 51:1–8

do Valle Matta MA, Jonniaux JL, Balzi E, Goffeau A, van den Hazel B (2001) Novel target genes of the yeast regulator Pdr1p: a contribution of the TPO1 gene in resistance to quinidine and other drugs. Gene 272:111–119

Gao X, Wang P, Tang Y (2010) Engineered polyketide biosynthesis and biocatalysis in Escherichia coli. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 88:1233–1242

Hutchinson CR, Kennedy J, Park C, Kendrew S, Auclair K, Vederas J (2000) Aspects of the biosynthesis of non-aromatic fungal polyketides by iterative polyketide synthases. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 78:287–295

Jaeheon LEE, Taehee HA, Chulhyun P, Hoechul LEE, Gwansun LEE, Youngkil C (2005) Process for the preparation of simvastatin. US patent, US, p 20050080275

Ley A, Coumou HC, Frandsen RJN (2015) Heterologous expression of MlcE in Saccharomyces cerevisiae provides resistance to natural and semi-synthetic statins. Metab Eng Commun 2:117–123

Liu Y, Bai C, Xu Q, Yu J, Zhou X, Zhang Y, Cai M (2018a) Improved methanol-derived lovastatin production through enhancement of the biosynthetic pathway and intracellular lovastatin efflux in methylotrophic yeast. Bioresour Bioprocess 5:22

Liu Y, Tu X, Xu Q, Bai C, Kong C, Liu Q, Yu J, Peng Q, Zhou X, Zhang Y, Cai M (2018b) Engineered monoculture and co-culture of methylotrophic yeast for de novo production of monacolin J and lovastatin from methanol. Metab Eng 45:189

Martín JF, Casqueiro J, Liras P (2005) Secretion systems for secondary metabolites: how producer cells send out messages of intercellular communication. Curr Opin Microb 8:282–293

Nikaido H, Takatsuka Y (2009) Mechanisms of RND multidrug efflux pumps. BBA-Proteins Proteom 1794:769–781

Saitou N, Nei M (1987) The neighbor-joining method: a new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol Biol Evol 4:406–425

Wang F, Lv X, Xie W, Zhou P, Zhu Y, Yao Z, Yang C, Yang X, Ye L, Yu H (2017) Combining Gal4p-mediated expression enhancement and directed evolution of isoprene synthase to improve isoprene production in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Metab Eng 39:257–266

Xie X, Tang Y (2007) Efficient synthesis of simvastatin by use of whole-cell biocatalysis. Appl Environ Microbiol 73:2054

Xu W, Chooi YH, Choi JW, Li S, Vederas JC, da Silva NA, Tang Y (2013) LovG: the thioesterase required for dihydromonacolin L release and lovastatin nonaketide synthase turnover in lovastatin biosynthesis. Angew Chem Int Ed 52:6472–6475

Zuckerkandl E, Pauling L (1965) Evolutionary divergence and convergence in proteins. In: Bryson V, Vogel HJ (eds) Evolving Genes and Proteins. Academic Press, New York, pp 97–166

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This work was supported by Fundamental Research Funds for the Shanghai Science and Technology Innovation Action Plan (Grant Number 17JC1402400) and the Shanghai Rising-Star Program, China (Grant Number 19QA1402700), the 111 Project of China (Grant Number B18022), the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities, China (Grant Number JKF012016019, 22221818014) and Research Program of State Key Laboratory of Bioreactor Engineering.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MC conceived the project and supervised the research. CB, YL and MC are responsible for project planning and experimental design. CB performed all of the experiments. XC and ZQ participated in construction of strains. HL participated in product analysis. CB, YL and MC analyzed the results. CB wrote the manuscript and MC revised and accomplished the manuscript finally. XZ and YZ reviewed the manuscript. All authors contributed to scientific discussion. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval and informed consent

We declare that this paper does not report any data collected from humans or animals.

Consent for publication

The authors approved the consent for publishing the manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1.

Additional figures and tables.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bai, C., Liu, Y., Chen, X. et al. Fungal statin pump protein improves monacolin J efflux and regulates its production in Komagataella phaffii. Bioresour. Bioprocess. 7, 32 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40643-020-00321-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40643-020-00321-x