Abstract

The paper investigates the reference corpus of a climate change contrarian report. We categorized the journal abstracts according to the endorsement positions on anthropogenic climate change. These results were contrasted by an in-text citation analysis. We focused here on the role of the papers included by the report editors concerning the mainstream claims around climate change. Our results showed moderate differences in the endorsement rates as well as in the sources of contrarian arguments considering the contrarian report in general and the presented journals specifically. These outcomes indicate differences among the journals regarding editorial practice, topic-dependency, and the home field advantage of some authors. Beyond the bibliometric data, our additional rhetorical analysis showed that language and wording are at least as important as the references backing the claims. The well-founded atmosphere of doubt in the climate skeptic report relies on two prevalent factors working together: relevant information accumulated on methodological uncertainties and findings that do not support mainstream knowledge claims (1); and solemn rhetoric supplemented with proper re-contextualization and reinterpretation (2).

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Climate change skepticism emerged in the 1990s, particularly after the 1997 Kyoto Agreement when several events hallmarked the evolving climate change controversy (Grundmann 2015). The 1998 ‘Chapter 8 Controversy’ was an early direct attack against the IPCC (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change) and its 1995 report. The ‘Chapter 8 Controversy’ essentially questioned the review policy and procedural rules the international body utilized (Edwards and Schneider 2001). Concurrently, the ‘Hockey Stick Controversy’—focusing on the third IPCC report on the physical science of climate change published in 2001 (Demeritt 2006; Frank et al. 2010)—began to gain momentum. Eleven years later, ‘Climategate’ opened the possibility of even more vehement attacks on the scientific community concerning climate change and the IPCC. As a result, the workings of the IPCC were scrutinized and reviewed (e.g. Berkhout 2010; Prins et al. 2010; IAC, 2010; Grundmann 2012, 2013; Maibach et al. 2012; Lahsen 2013a), as the political and scientific context of the IPCC is in a state of ongoing change (Beck and Mahony 2018). Paralleled with these cases, skeptics opposing the IPCC in 2009 and 2013 published several alternative climate change assessment reports.

As a consequence, research on the skeptic movement flourished. Beyond the movement’s social embeddedness, papers attempted to uncover the roots of the climate skeptic movement and its scientists (Lahsen 2008, 2013b; Björnberg et al. 2017; Van Rensburg and Head 2017) as well as the political and economic links and the workings of the movement (e.g. Jaques et al. 2008; Dunlap and McCright 2015; Petersen et al. 2019). Another research branch investigated the climate reality the skeptics constructed by using scientific (mis)information and rhetoric (Nerlich 2010; Jankó et al. 2014, 2017; Medimorec and Pennycook 2015; Boussalis and Coan 2016).

In earlier papers, Jankó et al. (2014, 2017) analyzed and compared the reference lists of the IPCC Working Group I. assessment reports Nos. 4 and 5 with the corresponding climate change skeptic reports of the conservative think tank, the Heartland Institute. Cook et al. (2013) provided the impetus to conduct an additional analysis concerning the scientific background of the skeptic reports. Cook et al. categorized nearly 12 000 peer reviewed journal abstracts according to author positions regarding anthropogenic climate change. Their results demonstrated that of the authors who expressed a position about the anthropogenic origins of global warming, 97.1% endorsed the consensus that humans cause climate change; however, 66.4% of the abstracts contained no signs of judgement concerning the matter.

Although debated (most recently see: Cook and Pearce 2020), we followed this study, and our paper sheds some light on the details of the scientific literature in the climate change skeptic assessment report by revealing the referenced papers’ positions concerning anthropogenic global warming (AGW). Using scientometric data and additional rhetorical analysis, we attempt to grasp the roles literature plays in forming and legitimizing the knowledge claims made in the reports. Or conversely, to show how contrarian authors used the literature that contained dissenting arguments. Hence, our research questions are the following: What is the difference among journals regarding the level of consensus endorsement and functions of in-text citations? Which major authors are sources of contrarian arguments? What are the rhetorical features of the citation technique in the climate skeptic report?

Material and methods

For the purposes of the study, we processed the references of a climate skeptic report Climate Change Reconsidered II (Idso et al. 2013) in a database, and excerpted the items published before 1991 (N = 228) and all papers not published in scientific journals (N = 351) (see Cook et al. 2013). Every reference received a journal code and repeatedly occurring references were omitted. Following this, all journal article abstracts were analyzed according to the Cook et al. (2013) method (see Table 2 of Cook et al. 2013, and Fig. 1 of Jankó et al. 2020). Cook et al. (2013) originally used seven categories: explicit endorsements and rejections of AGW were divided into quantified and non-quantified groups; implicit endorsement or rejection; and ‘no position’ abstracts. We made corrections only within the framework of the original method. Contrary to Cook et al. (2013), we immediately introduced an ‘uncertainty’ category and added a further category within the ‘no position’ category. After analyzing the supplementary material of Cook et al. (2013) and checking ‘no position’ abstracts, we noticed abstracts containing specific rhetoric with reference on expected climate change, on climate projections, or simply on global warming (a phrase implying the anthropogenic causes). Hence, we created a ‘no positon with axiomatic reference to AGW’ category to solve the assumed monotony of ‘no position’ papers (Table 1).

We also developed a second database to analyze the in-text citations’ functions and examine how references and citations serve the purposes of the contrarian editors and authors. Therefore, we investigated all the in-text citations and classified them into four categories: ‘supporting’ or ‘not supporting’ the AGW relevant (IPCC) claims about climate change, creating ‘uncertainty’ around the claims, or simply ‘neutral’, referring to a method or secondary information. Each reference that was used in different contexts was classified into a dominant category adhering to the following logic: ‘not supporting’ (the strongest function), ‘supporting’, ‘uncertainty’, or ‘neutral’ (the weakest) (examples can be found in Jankó et al. 2014). We also checked the occurrence of the so called ‘transferred citations’ to provide a nuanced picture on the journal statistics (Table. 1).

Every study coauthor participated in the abstract rating and in-text citation-analysis. Each coauthor received the same number of articles, which were rated by only one colleague. Before the actual work began, we conducted two test stages to adjust and harmonize each other’s work and make the method clear to all coauthors. Ultimately, our task is to underscore the uncertainty in this research, i.e. the sometimes vague language of the abstracts, as well as the subjectivity and different background of the coauthors (cf. Cook et al. 2013). The papers without abstracts (N = 86) or in-text citations (N = 37) were excluded from the databases. In the end, the two databases were merged, and thus a total of 3,135 papers with abstract ratings, and a total of 4,968 in-text citations were analyzed.

After the quantitative analysis, we sampled the papers (N = 90) for rhetorical analysis to focus on the interpretative techniques and rhetoric used by the climate skeptic report editors. The journal articles (i.e. the abstracts) in the sample explicitly endorsing AGW, while not supporting the IPCC knowledge claims as in-text functions, that promised to be the most distinctive cases for the rhetorical investigation.

Results

General data

Table 2 is a summary of the general statistics showing the distribution (in absolute and relative terms) between the different abstract rating and in-text function categories. Two basic statements emerge here. Firstly, as we compared our statistics derived from the climate skeptic report and those obtained from Cook et al. (2013), we can conclude that the main patterns are similar. ‘No position’ papers (‘no position’ and ‘no position with axiomatic reference on AGW’ altogether) also have the highest frequencies in the skeptic report, but at a higher level than presented by Cook et al. (79.8% to 66.4%). Hence, a relatively smaller proportion of papers (i.e. abstracts) endorsed AGW from the rest (74.7% to 97.1%) in the skeptic report. Further, we should see that 81.1% of the ‘not supporting’ in-text functions are provided by papers with ‘no position’ abstracts (see 69,6% + 11,5%). (Understandably, this data is higher (84,7%) only in the case of ‘neutral’ in-text functions.) This briefly suggests that the superficial climate debate on anthropogenic influence cannot be explained by the rhetorical state of the journal abstracts alone; because (neutral) rhetoric in terms of AGW is an important tool for scientists as well as for report editors who re-interpret these texts (see Jankó et al. 2020).

Secondly, there is a considerable but not deterministic relationship between abstract categories and in-text functions. Papers with abstracts explicitly or implicitly endorsing AGW serve the IPCC claims to a higher degree in the skeptic report, i.e. they have a ‘supporting’ in-text function in higher percentages. Nevertheless, it becomes clear that these papers with endorsing abstracts can also be used to back contrarian claims, which highlights the importance of the rhetorical analysis to be presented below. In fact, ‘not supporting’ function always shows the highest percentage among the abstract categories. The data of the two contrary, ‘supporting’ and ‘not supporting’ in-text functions’ are only equal in the case of the ‘explicit endorsement with quantification’ category. On the other hand, ‘not supporting’ functions have the highest frequencies in the case of explicitly or implicitly rejecting abstract categories, although the subsamples are quite small here.

Finally, it is important to note that 31.2% of the in-text citations are so-called ‘transferred citations’, which could also be viewed as an interpretative and rhetorical technique of the climate skeptic report to expand its reference base and legitimacy.

Forums of doubt

Taking the journal performances in the case of (explicit or implicit) AGW endorsement into consideration, Journal of Climate, Science, Geophysical Research Letters, Nature, and Journal of Geophysical Research have the most papers in absolute terms (between 31 and 62 items). The top journals featuring AGW rejection are Geophysical Research Letters (N = 23), Science (12), Journal of Atmospheric and Solar-Terrestrial Physics (8), Journal of Geophysical Research (6), and Journal of Climate (5). It is certainly needless to say that these absolute numbers show relatively low percentages (Table 3).

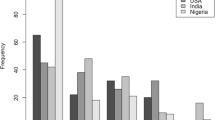

Figure 1 presents the relative distribution among all categories in the main journals, showing some distinctions between the journals, presumably due to scope, genre or some differences in editorial practice and expectations. For journals with a paleoclimate research focus ‘no-position’ abstracts are extremely common. While in the case of Nature, Journal of Climate and others, arguing about anthropogenic climate change is a more frequent practice. Higher proportions in rejecting categories could be identified only in some particular journals (e.g. Energy & Environment, Journal of Atmospheric and Solar-Terrestrial Physics) but their count numbers are rather small.

The time-profiles of the most important journals indicate different “endorsement histories” (Fig. 2). One characteristic trend is the evolving difference between ‘no position’ and endorsing abstracts from the end of the 1990s. Further, the larger frequency and, occasionally, the emerging curve of AGW endorsing abstracts in the cases of the Journal of Climate, Nature and Science is worth mentioning. The appearance of AGW rejecting papers in Geophysical Research Letters is yet to be noted from the beginning of the 2000s. Apart from that, the ‘no-position’ trend of the latter is more or less congruent with the entire sample highlighting the different trends in the other journals (cf. Jankó et al. 2020, Fig. 2). As we argued above, more than 80% of the papers with ‘not supporting’ in-text citations have ‘no-position’ ratings. This underscores that the potential of some journals to offer papers the skeptics could utilize has significantly decreased. This is visible in Fig. 2 as no-position papers peak in the middle of the period (first of all Science, Nature and The Holocene).

Figure 3 presents data concerning the in-text citation functions related to the IPCC claims and how the contrarian editors used the papers in wording the climate skeptic report. The journal profiles are similar as seen in Fig. 1. While Geophysical Research Letters stands in the middle, Nature and Science articles show lower rates in ‘not supporting’ and ‘uncertainty’ functions, and larger frequencies in ‘supporting’ functions. On the other side, paleoclimate journals have higher proportions of ‘not supporting’ citations, implying that paleoclimate research findings addressing the same climatic system, but without the human fingerprint and in a different manner, play a crucial role in climate skeptic argumentation. Implying the uncertainty of climate models is a usual method used by climate skeptics, hence, this function is higher among papers in Climate Dynamics and Journal of Climate, where climate modelling is in the main scope of the journals.

Based on the aspects we used so far, a modified journal list could also be presented as a foundation and source of contrarian arguments. Without the articles published before 1991, taking out papers only used as ‘transferred citations’ and those only supporting the IPCC claims with their in-text citation functions, Table 4 is obtained (compare with Table 2 in Jankó et al. 2017). Overall, nearly 35% of the journal articles have fallen off the list, although there is one example on the list, Journal of Glaciology, which paper count halved, which causes some moderate changes in the first half of the presented list and some greater changes below that.

Authors

The most frequently used and/or most cited lead authors are evident in Table 5. To show some interconnectedness in this list, we note that Cook, Esper and Meko are occasionally co-authors, similar to Scafetta and Loehle. The rhetorical state of the articles and their use in the text could be much more complicated and diverse. Some authors show a wide rhetorical range in their abstracts concerning the endorsement of AGW which indicates that rhetoric is accidental to a certain degree. In-text citations can also serve different functions, even in instances where these citations belong to the same author or to the same paper. For example a P. Chylek. article rated as implicitly endorsing AGW was used twice by the skeptic report against the IPCC knowledge claims. Another Chlyek study, implicitly rejecting AGW was cited two times for and three times against the IPCC claims. A similar example is E.R. Cook, who has three papers with IPCC supporting interpretations, two implicitly endorsing, but one implicitly rejecting AGW; however, the dominant in-text use for these is ‘not supporting’. These examples also demonstrate that scientific rhetoric in the abstracts and the life of papers could take different directions when they are cited later, at least in the hands of the climate skeptic report editors. Earlier research indicated the same papers could have different interpretations by the IPCC and by the climate skeptic report (Jankó et al. 2014). Table 5 makes it clear that there are also numerous articles with only transferred citations. Examples when only two papers deliver numerous in-text citations also exist. Nevertheless, there are only two authors (N. Scafetta and J. Esper), who could be highlighted by their high numbers in both aspects of our analysis, i.e. article and citation number.

Language

Our last analytical aspect was to study the rhetorical practice conducted in the climate skeptic report. The starting point of this investigation was the question of the seeming contradiction between abstracts endorsing AGW and the use of these as papers that do not support the IPCC knowledge claims. Thus, we selected those 90 articles that fit into these criteria. Firstly, all the abstracts were revisited to determine whether AGW endorsement was based on the study results, or whether the endorsement was only rhetorical in nature, i.e. writing about anthropogenic climate change as a known fact. This data showed that only 9 papers (10%) presented their results as a source of AGW endorsement. Secondly, the main message of the abstracts was identified and relatedly, the main points of the same papers as cited in the text were analyzed to determine whether a link exists, i.e. overlapping content between the two. We found 65 papers containing this relationship. As we argued elsewhere (Jankó et al. 2020), these examples not only show that papers in endorsing categories could be used to legitimize opposing claims but also reveal that results not fitting into the consensus or not reflecting the dominant climatic evidence could be presented using the AGW rhetoric. In the other cases (18 from 25), we have mostly transferred citations; thus, there is no need to explain the missing link. After all, in the remaining 7 studies, we should emphasize that the abstract scope and content does not match either the reviewed part or the highlighted message of a given paper.

In Table 6 we show three examples. The main message of the first abstract is that there are widespread positive temperature trends in the Antarctic summer, which should be monitored to determine the balance between natural and anthropogenic forcings. In contrast, the skeptic report highlights that the warming on the Antarctic Peninsula is only a small scale anomaly, and that near surface temperature trends in Antarctica were not statistically significant. In the second example, the abstract concludes that warming after 1920 was caused mainly by atmospheric trace gases; however, other natural forcings also played a role. The skeptic report questioned the carbon-dioxide–global temperature warming link using the findings from the same paper. In the third example, the abstract addresses the studied sea level changes and the response of the Chukchi Sea, while the skeptic assessment reported about the missing positive relationship between storm frequency and warmer climatic conditions. These situations could be easily explained as ‘cherry picking’ (see Farmer and Cook 2013); however, we should be wary of such a superficial judgement because abstracts cannot and should not reflect all the findings in scientific papers.

In a rhetorical sense, several things could happen to a given paper when we place it into the citation context. As we pointed out earlier, solemn language, i.e. epideictic in Aristotelian sense, characterizes the climate skeptic report (Jankó et al. 2014). Medimorec and Pennycook (2015) showed this rhetoric parallels with more certainty in wording the arguments that have clearly visible links to the language of science popularizations (Fahnestock 1986). Unsurprisingly, solemn language was the most common type of rhetoric, appearing in 51 of the 90 papers. The script of such a citation is easy to follow. First, the subject is highlighted. Second, the research venue and method are addressed and sometimes celebrated as a source of legitimation. After that, the report editors turn to the results and discuss what the authors found and how the authors concluded, regularly using quotations and ‘transferred citations’ from the original text for further support.

Beyond the pure category, it was possible to identify a number of versions of this rhetoric. For example, the skeptic report authors rectify the message of the cited paper through the overstatement and re-contextualization of the results, or through the reinterpretation and supplementation of the conclusions of the cited papers (Table 7, examples No. 3–6.). In these cases, the opportunities of rhetoric are demonstrated, how a different context amplifies or blurs the original intention of the papers and their authors. However, the technique of reinterpretation is nothing but a regular, in fact an expected activity of reviewers and report editors.

Nevertheless, the second-most common rhetorical technique was neutral (N = 34). In these cases, the rhetorical context of the so called ‘transferred citations’ has barely changed by moving them from the citing paper to the report, and were often shown within a word-for-word quotation. The role of the ‘transferred citations’ was to legitimize the papers citing them, thereby legitimizing the reviewing editors’ claims.

Conclusions

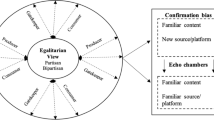

Concluding concerning the research questions, our study showed that the reference corpus of the contrarian report has remarkable deflection, particularly with its distinct endorsing rates pushing further questions to the foreground. The discrepancy between similarly high endorsing rates and the majority of non-supporting citations against the IPCC claims could be resolved with some focus on rhetoric. First, rhetoric is important, as our analysis showed AGW endorsement is mainly a rhetorical action. Thus, endorsement in abstracts is not in conflict with the “skeptical use” of papers. Second, rhetorical analysis showed that language and wording are at least as important as the references backing the claims, i.e. this method is a proper complement to the bibliometric numbers characterizing the literature. Digging to the deepest point before reading all the references again, we revealed significant differences in the forums where the papers were published concerning editorial practice, topic-dependency, and certain home field advantages of some authors. Nevertheless, in a particular sense, the whole skeptic report could be characterized as a collection of cherry-picked information and research findings indicating the uncertainties of methods and not supporting the IPCC knowledge claims. These are all decontextualized and re-contextualized into the frames of the skeptical argumentation. Doubt about the anthropogenic influence on climate change has thus the following foundations. Authors and forums (i.e. journals), willingly or unwillingly delivering relevant information accumulated on methodological uncertainties and findings that do not support mainstream knowledge claims (1), and rhetoric, especially solemn rhetoric supplemented with proper re-contextualization and reinterpretation (2).

References

Beck, S., & Mahony, M. (2018). The IPCC and the new map of science and politics. WIREs Climate Change. https://doi.org/10.1002/wcc.547.

Berkhout, F. (2010). Reconstructing boundaries and reason in climate debate. Global Environmental Change,20, 565–569.

Björnberg, K. E., Karlsson, M., Gilek, M., & Hansson, S. O. (2017). Journal of Cleaner Production. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.08.066.

Boussalis, C., & Coan, T. G. (2016). Text-mining the signals of climate change doubt. Climatic Change,36, 89–100. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2015.12.001.

Cook, J., Nuccitelli, D., Green, S. A., Richardson, M., Winkler, B., Painting, R., et al. (2013). Quantifying the consensus on anthropogenic global warming in the scientific literature. Environmental Research Letters,8(2), 024024. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/8/2/024024.

Cook, J., & Pearce, W. (2020). Is emphasizing consensus in climate science helpful for policymaking? In M. Hulme (Ed.), Contemporary Climate Change Debates. A Student Primer. Abingdon: Routledge.

Dunlap, R. E., & McCright, A. M. (2015). Challenging climate change: The denial countermovement. In R. E. Dunlap & R. J. Brulle (Eds.), Climate change and society: Sociological perspectives (pp. 300–332). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Edwards, P. N., & Schneider, S. H. (2001). Self-Governance and peer review in science-for-policy: The case of the IPCC second assessment report. In C. A. Miller & P. N. Edwards (Eds.), Changing the Atmosphere: Expert Knowledge and Environmental Governance (pp. 219–246). Cambridge: The MIT Press.

Fahnestock, J. (1986). Accomodating science: The rhetorical life of scientific facts. Written Communication,3(3), 275–296. https://doi.org/10.1177/0741088386003003001.

Farmer G. T. & Cook J. (2013). Understanding Climate Change Denial. In G. T. Farmer & J Cook (Eds.), Climate Change Science: A Modern Synthesis, Volume I. - The Physical Climate, (pp. 445–466). Springer, Dordrecht. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-5757-8_3.

Frank, D., Esper, J., Zorita, E., & Wilson, R. (2010). A noodle, hockey stick, and spaghetti plate: A perspective on high-resolution paleoclimatology. WIREs Climate Change,1(4), 507–516.

Grundmann, R. (2012). The legacy of climategate: Revitalizing or undermining climate science and policy? WIREs Climate Change,3(3), 281–288. https://doi.org/10.1002/wcc.166.

Grundmann, R. (2013). ‘‘Climategate’’ and the scientific ethos. Science, Technology & Human Values,38(1), 67–93.

Grundmann, R. (2015). Climate skepticism. In K. Bäckstrand & E. Lövbrand (Eds.), Research Handbook on Climate Governance (pp. 175–187). Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

IAC, 2010. Climate Change Assessments. Review of the Processes and Procedures of the IPCC. InterAcademy Council, Committee to Review the IPCC, Amsterdam: InterAcademy Council. <https://reviewipcc.interacademycouncil.net/report.html> (accessed 24.02.11).

Idso, C. D., Carter, R. M., & Singer, S. F. (Eds.). (2013). Climate change reconsidered II: Physical science (p. 993). Chicago, IL: The Heartland Institute.

Jankó, F., Móricz, N., & Papp-Vancsó, J. (2014). Reviewing the climate change reviewers: Exploring controversy through report references and citations. Geoforum,56, 17–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2014.06.004.

Jankó, F., Papp-Vancsó, J., & Móricz, N. (2017). Is climate change controversy good for science? IPCC and contrarian reports in the light of bibliometrics. Scientometrics,112, 1745–1759. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-017-2440-9.

Jankó, F., Drüszler, Á., Gálos, B., Móricz, N., Papp-Vancsó, J., Pieczka, I., et al. (2020). Recalculating climate change consensus: The question of position and rhetoric. Journal of Cleaner Production,254, 120127.

Jaques, P. J., Dunlap, R. E., & Freeman, M. (2008). The organisation of denial: conservative think tanks and environmental skepticism. Environmental Politics,17(3), 349–385.

Lahsen, M. (2008). Experiences of modernity in the greenhouse: A cultural analysis of a physicist ‘‘trio’’ supporting the backlash against global warming. Global Environmental Change,18, 204–219.

Lahsen, M. (2013a). Climategate: The role for the social sciences. Climatic Change,119, 547–558. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-013-0711-x.

Lahsen, M. (2013b). Anatomy of dissent. A cultural analysis of climate skepticism. American Behavioral Scientist,57(6), 732–753.

Maibach, E., Leiserowitz, A., Cobb, S., Shank, M., Cobb, K. M., & Gulledge, J. (2012). The legacy of climategate: Undermining or revitalizing climate science and policy? WIREs Climate Change,3(3), 289–295. https://doi.org/10.1002/wcc.168.

Medimorec, S., & Pennycook, G. (2015). The language of denial: Text analysis reveals differences in language use between climate change proponents and skeptics. Climatic Change,133(4), 1–9.

Nerlich, B. (2010). ‘Climategate’: Paradoxical metaphors and political paralysis. Environmental Values,19(4), 419–442.

Petersen, A. M., Vincent, E. M., & Westerling, A. L. (2019). Discrepancy in scientific authority and media visibility of climate change scientists and contrarians. Nature Communications,10, 3502. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-09959-4.

Prins, G., Galiana, I., Green, C., Grundmann, R., Hulme, M., Korhola, A., Laird, F., Nordhaus, T., Pielke Jr., R.A., Rayner, S., Sarewicz, D., Shellenberger, M., Stehr, N. & Tezuka, H., (2010). The Hartwell Paper⁄ A New Direction for Climate Policy after the Crash of 2009. University of Oxford, Institute for Science, Innovation and Society; LSE Mackinder Programme (accessed 24.02.11 eprints.lse.ac.uk/27939/).

Van Rensburg, W., & Head, B. W. (2017). Climate change sceptical frames: The case of seven Australian sceptics. Australian Journal of Politics and History,63(1), 112–128.

David Demeritt, (2006) Science studies, climate change and the prospects for constructivist critique. Economy and Society 35 (3):453–479

Ackowledgements

Open access funding provided by Eötvös Loránd University. We are very thankful for the valuable suggestions and comments from all the reviewers of this paper. This work was supported by the project „EFOP-3.6.1-16-2016-00018 – Improving the role of research+development+innovation in the higher education through institutional developments assisting intelligent specialization in Sopron and Szombathely” (Jankó) and Hungarian Scientific Research Fund under grant K-129162 (Pieczka, Pongrácz, Soósné Dezső) and János Bolyai Research Scholarship of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences (Soósné Dezső). The founding sources had no involvement in the conduct of the research and preparation of the article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Jankó, F., Drüszler, Á., Gálos, B. et al. Sources of doubt: actors, forums, and language of climate change skepticism. Scientometrics 124, 2251–2277 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-020-03552-z

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-020-03552-z