Abstract

Although female involvement in science and technology has been growing over recent years, it is still low. Latin America is no exception. Even though the Latin American region has achieved significant accomplishments in terms of gender parity, women’s participation in patenting activities remains small compared to that of men. The aim of this study is to explain the rate of female participation in patenting activity. We gather information from 3081 US patents granted to assignees in Latin America. The countries of our sample are Argentina, Brazil, Costa Rica, Chile, Cuba, Colombia, México, Panamá, Peru, Uruguay, and Venezuela. The study period is from 1976 to 2011. This study reveals that the number of US patent granted with female involvement to the countries in our sample is only 22%. We use a probit model to explain women participation in patenting. Results suggest that external and internal collaboration, the institutional sector of the grantee, and innovations related to the life sciences have an effect on the probability of having female participation in patenting in Latin America. Our findings also show that the fertility rate and the human development of countries impact women participation in patenting in the Latin American region.

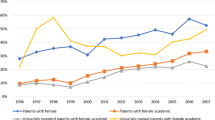

Source: Own elaboration based on the USPTO database

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

We use the patent document to check whether an invention is shared by different organizations and take that as an external linkage, a proxy for external collaboration. There are different types of external linkages, and not all involve sharing patent rights; however, because there are no available databases on alliances in Latin America, we decided to use the patent document even though it has limitations for measuring collaboration.

The top five patenting firms in our sample are Intevep, Petrobras, Empresa Brasileira de Compressores S.A, Hylsa S.A. de C.V., Vitro Monterrey. These companies are either monopolies or oligopolies, and are natural resource-based companies.

Jung and Ejermo (2014) use technology fields to study demographic patenting trends by gender and technology.

There exist different abbreviations for companies registered by civil law in Latin America. The most common of these abbreviations are S.A (65.4% of our total sample of firms is registered under this abbreviation), Ltd. (13.2% of the total sample of firms), and Ltda. (9.6% of the total sample of firms). We also look at other abbreviations even though they are not common: S. de R.L., S.A de C.V, and C.A, among others.

Leydesdorff and Meyer (2010) have pointed out that some universities have been named “institutes,” and that this may lead to an underestimation of the number of universities. We took care of it and found that 18.8% of the US utility patents granted to Latin American universities are under the assignee name “Instituto.” The most common cases are the patents granted to Instituto Politécnico Nacional (Mexico).

We searched for their corresponding Spanish or Portuguese words in the assignee name and found that most patents in this category were granted to “Centros de Investigación/Research Centers” (110 patents), followed by “Institutos/Institutes” (94 patents) and “Fundacao/Fundación/Foundations” (54 patents). We also noticed that there exist a few cases in which a patent is granted to governmental entities such as national councils of science or ministries. These last cases represent around 0.6% of our sample, and the assignee countries were Argentina, Mexico, Chile, Colombia, and Venezuela. We also take into account these cases in our study.

The section category of the IPC represents the whole body of knowledge that may be regarded as proper to the field of patents for invention; the subsections are informative headings in between sections; the class category is the second hierarchical level of the classification; and the subclass category represents the third hierarchical level of the classification, World Intellectual Property Organization (2019).

As previously mentioned, when a patent holder is an individual also listed as an inventor, we take that as a non-affiliated inventor.

It is possible that two or more organizations share patent rights and only one individual is listed as an inventor. We also take that as an external collaboration because even though there is only one inventor, organizations are allies to carry out an invention. It is also likely that organization(s) and individual(s) are listed as assignees, this is a very unusual case, only 11 patents out of 3081 show that feature (0.3% of the patents in our sample). In this case, we check whether there were one or more individuals listed as inventors and/or the individual(s) were affiliated to the patent holder. Upon that screening, we classify the 11 patents accordingly.

We follow Meng (2016) and consider biotechnology and nanotechnology as technological fields related to the life sciences. However, when searching for nanotechnology patents, there are no nano US patents granted to our sample of Latin America in our study period.

We use 100 patents as a target because that indicates there is at least an effort to receive two patents on an average per year by a country.

When interpreting our estimates of the average of independent dummy variables, we paid careful attention to the meaning of them.

References

Abreu, M., & Grinevich, V. (2017). Gender patterns in academic entrepreneurship. The Journal of Technology Transfer,42(4), 763–794.

Aghion, P., & Tirole, J. (1994). The management of innovation. The Quarterly Journal of Economics,109(4), 1185–1209.

Bear, J. B., & Woolley, A. W. (2011). The role of gender in team collaboration and performance. Interdisciplinary Science Reviews,36(2), 146–153.

Bell, A., Chetty, R., Jaravel, X., Petkova, N., & Van Reenen, J. (2019). Who becomes an inventor in America? The importance of exposure to innovation. The Quarterly Journal of Economics,134(2), 647–713.

Bonder, G. (2019). Planes de igualdad de género en universidades y centros de investigación de América Latina. Reunión entre representantes—Informe final. Proyecto ACTonGender, FLACSO, Argentina, Cátedra Regional Unesco Mujer, Ciencia y Tecnología en América Latina.

Bukstein, D., & Gandelman, N. (2019). Glass ceilings in research: Evidence from a national program in Uruguay. Research Policy,48(6), 1550–1563.

Busolt, U., & Kugele, K. (2009). The gender innovation and research productivity gap in Europe. International Journal of Innovation and Sustainable Development,4(2–3), 109–122.

Cepeda, B., Gonzalez, C., & Perez, M. A. (2017). Gender desegregated analysis of Mexican inventors in patent applications under the patent cooperation treaty (PCT). Interciencia,42(4), 204–211.

Chioda, L. (2016). Work and family: Latin American and Caribbean women in search of a new balance. Latin American Development Forum Series. Washington, D.C.: World Bank Group.

Crespi, G., Katz, J., & Olivari, J. (2018). Innovation, natural resource-based activities and growth in emerging economies: The formation and role of knowledge-intensive service firms. Innovation and Development,8(1), 79–101.

Ding, W. W., Murray, F., & Stuart, T. E. (2006). Gender differences in patenting in the academic life sciences. Science,313(5787), 665–667.

Ding, W. W., Murray, F., & Stuart, T. E. (2013). From bench to board: Gender differences in university scientists’ participation in corporate scientific advisory boards. Academy of Management Journal,56(5), 1443–1464.

EIGE. (2017). Economic benefits of gender equality in the European Union. Luxemburg: Publications Office of The European Union.

Esquivel, G. (2015). Desigualdad extrema en México: Concentración del poder económico y político. Mexico City: Oxfam Mexico.

Filson, D., & Morales, R. (2006). Equity links and information acquisition in biotechnology alliances. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization,59(1), 1–28.

Foxley, A. (2016). Inclusive development: Escaping the middle-income trap. In A. Foxley & B. Stallings (Eds.), Innovation and inclusion in Latin America: Strategies to avoid the middle income trap (pp. 33–57). New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Frietsch, R., Haller, I., Funken-Vrohlings, M., & Grupp, H. (2009). Gender-specific patterns in patenting and publishing. Research Policy,38(4), 590–599.

Gallego, J. M., & Gutiérrez Urdaneta, L. H. (2018). An integrated analysis of the impact of gender diversity on innovation and productivity in manufacturing firms. IDB Working Paper Series No. IDB-WP-865. Inter-American Development Bank.

Giuri, P., Grimaldi, R., Kochenkova, A., et al. (2020). The effects of university-level policies on women’s participation in academic patenting in Italy. The Journal of Technology Transfer, 45, 122–150.

Guerrero, I., López-Calva, L. F., & Walton, M. (2009). The inequality trap and its links to low growth in Mexico. In S. Levy & M. Walton (Eds.), No growth without equity? Inequality, interests, and competition in Mexico (pp. 111–156). New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Heikkilä, J. (2019). IPR gender gaps: A first look at utility model, design right and trademark filings. Scientometrics,118(3), 869–883.

Hunt, J., Garant, J.-P., Herman, H., & Munroe, D. J. (2013). Why are women underrepresented amongst patentees? Research Policy,42(4), 831–843.

Jensen, K., Kovács, B., & Sorenson, O. (2018). Gender differences in obtaining and maintaining patent rights. Nature Biotechnology,36(4), 307.

Jung, T., & Ejermo, O. (2014). Demographic patterns and trends in patenting: Gender, age, and education of inventors. Technological Forecasting and Social Change,86, 110–124.

Katz, J. S., & Martin, B. R. (1997). What is research collaboration? Research Policy,26(1), 1–18.

Kobeissi, N. (2010). Gender factors and female entrepreneurship: International evidence and policy implications. Journal of international entrepreneurship,8(1), 1–35.

Kugele, K. (2007). Patents invented by women and their participation in research and development: A European comparative approach. In: Godfroy-Genin, A.-S. (Ed.). Women in engineering and technology research. Proceedings of the PROMETEA Conference, París Octubre 26–27, 2007.

Lax, G., Raffo, J., & Saito, K. (2016). Identifying the gender of PCT inventors. World Intellectual Property Organization-Economics and Statistics Division (No. 33).

Leahey, E., & Blume, A. (2017). Elucidating the process: Why women patent less than men. In Gender and entrepreneurial activity. Edward Elgar Publishing.

Leydesdorff, L., & Meyer, M. (2010). The decline of university patenting and the end of the Bayh-Dole effect. Scientometrics,83(2), 355–362.

López-Bassols, V., Grazzi, M., Guillard, C., & Salazar, M. (2018). Las brechas de género en ciencia, tecnología e innovación en América Latina y el Caribe. División de Competitividad, Tecnología e Innovación. Nota Técnica nº idb-tn-1408.

Maldonado, K., Guzmán, A., & Peredo, F. (2015). La actividad inventiva de las mujeres en Brasil, 1997–2013. Economía: teoría y práctica, (spe3) (pp. 53–81).

Mani, S. (2001). Government, innovation and technology policy: An analysis of the Brazilian experience during the 1990s. Maastricht: UNU/INTECH Discussion Paper Series, 11.

Mauleón, E., & Bordons, M. (2010). Male and female involvement in patenting activity in Spain. Scientometrics,83(3), 605–621.

Mauleón, E., & Bordons, M. (2014). Indicadores de actividad tecnológica por género en España a través del estudio de patentes europeas. Revista Española de Documentación Científica,37(2), 043.

Mauleón, E., & Bordons, M. (2017). Patenting activity in Spain: A gender perspective. In Technology, commercialization and gender (pp. 77–100). Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

Mauleón, E., Daraio, C., & Bordons, M. (2014). Exploring gender differences in patenting in Spain. Research Evaluation,23(1), 62–78.

McMillan, G. (2009). Gender differences in patenting activity: An examination of the US biotechnology industry. Scientometrics,80(3), 683–691.

Meng, Y. (2016). Collaboration patterns and patenting: Exploring gender distinctions. Research Policy,45(1), 56–67.

Meng, Y. (2018). Gender distinctions in patenting: Does nanotechnology make a difference? Scientometrics,114(3), 971–992.

Meng, Y., & Shapira, P. (2010). Women and patenting in nanotechnology: Scale, scope and equity. In Nanotechnology and the challenges of equity, equality and development (pp. 23–46). Springer.

Milli, J., Gault, B., Williams-Baron, E., Xia, J., & Berlan, M. (2016). The gender patenting gap. The Institute for Women’s Policy Research Briefing Paper, July IWPR #C441.

Morales, R., & Sifontes, D. (2014). La Actividad Innovadora por Género en América Latina: un estudio de patentes. Revista Brasileira de Inovação,13(1), 163–186.

Murray, F., & Graham, L. (2007). Buying science and selling science: Gender differences in the market for commercial science. Industrial and Corporate Change,16(4), 657–689.

Naldi, F., Luzi, D., Valente, A., & Parenti, I. V. (2004). Scientific and technological performance by gender. In Handbook of quantitative science and technology research (pp. 299–314). Springer.

Puentes, G., & Toribio, R. (2016a). The effects of gender on the quality of university patents and public research centres in Andalusia: Is it better with a female presence? Economics and Sociology,9(1), 220–236.

Puentes, G., & Toribio, R. (2016b). Understanding the factors which engage female participation in patents in Andalusia (Spain). International Journal of Contemporary Management,15(4), 57–75.

Rivera León, L., Mairesse, J., & Cowan, R. (2017). Gender gaps and scientific productivity in middle-income countries: Evidence from Mexico. IDB Working Paper Series No. IDB-WP-800. Inter-American Development Bank.

Rosa, P., & Dawson, A. (2006). Gender and the commercialization of university science: Academic founders of spinout companies. Entrepreneurship and Regional Development,18(4), 341–366.

Samandar, M., & Bagheri, S. K. (2015). Gender gap in patenting activities: Evidence from Iran. Laboratory of economics and management (LEM), Sant Anna School of Advanced Studies, Pisa, Italy. (No. 2015/22).

Schmoch, U. (2008). Concept of a technology classification for country comparisons. Final report to the world intellectual property organisation (wipo), WIPO.

Smith-Doerr, L. (2004). Flexibility and fairness: Effects of the network form of organization on gender equity in life science careers. Sociological Perspectives,47(1), 25–54.

Stephan, E., & El-Ganainy, A. (2007). The entrepreneurial puzzle: Explaining the gender gap. The Journal of Technology Transfer,32(5), 475–487.

Sugimoto, C. R., Ni, C., West, J. D., & Larivière, V. (2015). The academic advantage: Gender disparities in Patenting. PLoS ONE,10(5), e0128000.

Tartari, V., & Salter, A. (2015). The engagement gap: Exploring gender differences in University-Industry collaboration activities. Research Policy,44(6), 1176–1191.

Thursby, J. G., & Thursby, M. C. (2005). Gender patterns of research and licensing activity of science and engineering faculty. Journal of Technology Transfer,30, 343–353.

Toole, A., Breschi, S., Miguelez, E., Myers, A., Ferrucci, E., Sterzi, V., Lissoni, F., & Tarasconi, G. (2019). Progress and potential: A profile of women inventors on US patents. Technical Report. US Patent & Trademark Office, Office of the Chief Economist.

UKIPO. (2016a). Gender profiles in UK patenting: An analysis of female inventorship. UK Intellectual Property Office Informatics Team, March, 2016.

UKIPO. (2016b). Gender profiles in worldwide patenting: An analysis of female inventorship. UK Intellectual Property Office Informatics Team, September, 2016.

UNESCO. (2019). Women in science. Fact Sheet No. 55 June FS/2019/SCI/55 UNESCO Institute for Statistics (UIS).

United Nations Development Programme. (2019). Human Development Index [Data file]. http://hdr.undp.org/en/indicators/137506#.

Whittington, K. B. (2009). Patterns of male and female scientific dissemination in public and private science. In Science and engineering careers in the united states: An analysis of markets and employment (pp. 195–228). University of Chicago Press.

Whittington, K. B. (2011). Mothers of invention? Gender, motherhood, and new dimensions of productivity in the science profession. Work and Occupations,38(3), 417–456.

Whittington, K. B. (2018). A tie is a tie? Gender and network positioning in life science inventor collaboration. Research Policy,47(2), 511–526.

Whittington, K. B., & Smith-Doerr, L. (2005). Gender and commercial science: Women’s patenting in the life sciences. The Journal of Technology Transfer,30(4), 355–370.

Whittington, K. B., & Smith-Doerr, L. (2008). Women inventors in context: Disparities in patenting across academia and industry. Gender and Society,22(2), 194–218.

WIPO. (2018). World intellectual property indicators 2018. Geneva: World Intellectual Property Organization.

WIPO. (2019). Guide to the international patent classification, (version 2019). World Intellectual Property Organization, Switzerland.

Woolley, A., Chabris, C., Pentland, A., Hashmi, N., & Malone, T. W. (2010). Evidence for a collective intelligence factor in the performance of human groups. Science,330(6004), 686–688.

World Bank, World Development Indicators. (2019). Fertility rate, total (births per woman) [Data file]. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.DYN.TFRT.IN.

Yáñez, S. (2016). Trayectorias laborales de mujeres en ciencia y tecnología. Barreras y desafíos. Un estudio exploratorio. Flacso-Chile. Documento de trabajo No, 2, Junio.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

A version of this paper was presented at the “1st Conference of the Latin American Network on Economics of Innovation and Entrepreneurship” as part of Domingo Sifontes’s doctoral dissertation. Domingo Sifontes thanks Roberto Alvarez and participants in the seminar for comments. We thank two anonymous referees for comments and suggestions. Both authors thank Angélica Rodríguez, Héctor Monasterios, Yuneigla Gomez, Jesús Obelmejias, Armando Romero, and Octavio Gonzalez for data collection.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Sifontes, D., Morales, R. Gender differences and patenting in Latin America: understanding female participation in commercial science. Scientometrics 124, 2009–2036 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-020-03567-6

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-020-03567-6