Abstract

Background

Rice blast is an economically important and mutable disease of rice. Using host resistance gene to breed resistant varieties has been proven to be the most effective and economical method to control rice blast and new resistance genes or quantitative trait loci (QTLs) are then needed.

Results

In this study, we constructed two advanced backcross population to mapping blast resistance QTLs. CR071 and QingGuAi3 were as the donor parent to establish two BC3F1 and derived BC3F2 backcross population in the Jin23B background. By challenging the two populations with natural infection in 2011 and 2012, 16 and 13 blast resistance QTLs were identified in Jin23B/CR071 and Jin23B/QingGuAi3 population, respectively. Among Jin23B/CR071 population, 3 major and 13 minor QTLs have explained the phenotypic variation from 3.50% to 34.08% in 2 years. And, among Jin23B/QingGuAi3 population, 2 major and 11 minor QTLs have explained the phenotypic variation from 2.42% to 28.95% in 2 years.

Conclusions

Sixteen and thirteen blast resistance QTLs were identified in Jin23B/CR071 and Jin23B/QingGuAi3 population, respectively. QTL effect analyses suggested that major and minor QTLs interaction is the genetic basis for durable blast resistance in rice variety CR071 and QingGuAi3.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Rice (Oryza sativa) is a staple food crop for more than 50% of the world’s population. Rice blast, caused by the fungal pathogen Magnaporthe oryzae, is one of the most serious diseases of rice in tropical and temperate areas of the world. Improving disease resistance in crops is crucial for stable food production. Nevertheless, using host resistance gene (R gene) to breed resistant varieties has been proven to be the most effective and economical method to control rice blast, and gene pyramiding is a promising method for providing broad-spectrum and durable resistance (Fukuoka et al. 2009; Liu et al. 2016; Tabien et al. 2002).

So far, over 100 blast resistant genes or quantitative trait loci (QTL) have been identified (Su et al. 2015; Vasudevan et al. 2016; Xiao et al. 2017; Zheng et al. 2016). Among them, 37 genes have been cloned (Wang et al. 2017; Wang et al. 2019; Zhao et al. 2018), and most of them belong to the nucleotide-binding site (NBS) leucine-rich repeat (LRR) gene family. Many of these R genes are clustered in the rice genome, especially on chromosomes 6, 11, and 12. Notably, at least 11 R genes have been identified, including Pi2, Pi9, Pi22, Pi25, Pi26, Pi40, Pi42, Pigm, Piz, Pizt, and Pi50, which are concentrated as gene clusters in the short-arm region near the centromere of chromosome 6. Of these, Pi2, Pi9, Pi50, Pigm, and Pizt have been cloned and have shown broad-spectrum resistance (Deng et al. 2017; Qu et al. 2006; Su et al. 2015; Zhou et al. 2006). It had been reported that at least 7 R genes were located in the long-arm of rice chromosome 11, including Pik, Pi-kg(t), Pikm, Pik-h, Pik-p, Pi54 and Pi1 (Ashikawa et al. 2008; Hua et al. 2012; Pan et al. 1998; Sharma et al. 2010; Yuan et al. 2011; Zhai et al. 2011; Zhai et al. 2014). More than 20 R gene were located on rice chromosome 12, most of them were located near the centromere of chromosome 12, including Pi-ta, Pi-ta2, Pi-tan, Pi19, Pi20, Pi30, Pi31 and Ptr (Bryan et al. 2000; Hayashi et al. 1998; Imbe et al. 1997; Sallaud et al. 2003; Zhao et al. 2018).

Although the use of race-specific resistance genes is a major strategy for disease control, these genes are vulnerable to counter evolution of pathogens. Consequently, most varieties lose their resistance after a few years because of new M. oryzae races. Many studies indicated that the genetic control of blast resistance is complex and involves both major and minor resistance genes with complementary or additive effects, as well as environmental interactions (Bonman 1992; Li et al. 2007; Li et al. 2011; Wang et al. 1994; Wu et al. 2005). New resistance genes are then needed, thus continuing a cycle referred to as an evolutionary “arms race” between crops and pathogens (Jones and Dangl. 2006). Quantitative trait loci, which usually have smaller individual effects than R genes but confer broad-spectrum or non-race-specific resistance, can contribute to durable disease resistance (Kou and Wang. 2010). Thus, the discovery and use of novel QTLs and development of broad-spectrum resistant varieties are urgent goals in breeding for blast resistance in rice.

Most blast resistance genes confer complete and race-specific resistances that the highly variable fungus can overcome the R gene effects within 2 or 3 years after planting (Wang et al. 2017). The resistance conferred by R genes often do not support sustainable crop production. However, resistance controlled by partially effective resistance genes is often considered to be non race-specific and therefore durable. Durable resistance is the main goal of rice breeding, repeated observations generally suggest that cultivars carrying partial resistance maintain resistance for a long time, possibly because of decreased selection pressure upon the pathogen. CR071 and QingGuAi3 are indica rice (Oryza sativa L.) cultivar that has provided a high level of durable resistance to blast over past decades, and has been used as a donor of blast resistance in breeding in China. To understand the genetic mechanism of blast resistance in CR071 and QingGuAi3, two advanced backcross population BC3F1 and derived BC3F2 population from Jin23B/CR071 and Jin23B/QingGuAi3 were studied for blast response under conditions of natural infection. The objective was to find blast resistance loci in the donor parents and to explain the underlying mechanism of resistance. Such results should be useful for improving blast resistance in rice breeding.

Materials and Methods

Experimental Population

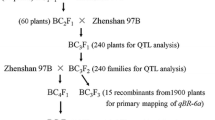

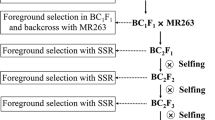

The blast resistant indica cultivar CR071 and QingGuAi3 which provided by the Enshi Academy of Agricultural Science, Hubei, China, were used as the donor parent. CR071 and QingGuAi3 were blast resistance varieties which have a high and durable resistance to rice blast since 1983 (Wu et al. 2001). The blast susceptible indica cultivar Jin23B, the maintainer line for several elite hybrids in China, was used as the recurrent parent. Two backcross populations derived from the cross between Jin23B and CR071 and between Jin23B and QingGuAi3 were generated according to the plan outlined in Fig. 1. After the first cross, the F1 generations were backcross to Jin23B, then the BC1F1 seeds were sown in a blast nursery in Xianfeng County, Hubei province, in 2010. Resistance plants identified by their leaf blast reactions were further backcrossed with the recurrent parent Jin23B, and BC2F1 plants were obtained. The BC2F1 seeds were sown in Hainan province in 2011 and were randomly crossed with Jin23B (Fig. 1), two backcross population contained 239 and 237 plants, respectively were obtained. The BC3F1 plants and parents were planted during the normal rice growing seasons (from mid-May to early October) at the experimental field of Xianfeng for phenotypic measurement in 2011 and selfed to produce BC3F2 families. In 2012, the BC3F2 families, each containing 12 plants, were grown in Xianfeng County for blast phenotyping. Selected lines in the BC3F1 population were backcross to Jin23B to obtain BC4F1, and the self-cross seed of these BC4F1 plants were used to develop BC4F2 segregating population of each QTL. The BC4F2 segregating populations of qBR3–3 and qBR6 from CR071 and qBR6 and qBR7–1 from QingGuAi3 were planted in 2013 in Xianfeng. Varieties BL6 and CO39 were used as resistant and susceptible control.

Trait Evaluations

All plants of the BC3F1 population were scored for leaf blast response at tillering and heading stages and were recorded for neck blast at maturation stages in 2011; the three traits were named 11RT (leaf blast response of plants at tillering, 2011), 11RH (leaf blast response of the plants at heading, 2011) and 11RN (neck blast of the plants at maturation, 2011). The BC3F2 populations were scored on an individual plant basis for leaf blast at tillering heading and for neck blast at the maturation stage, 2012, and results were named 12RT (leaf blast response of plants at tillering, 2012), 12RH (leaf blast response of plants at heading, 2012) and 12RN (neck blast of the plants at maturation, 2012). For the BC3F2 families, 24 plants of each family were planted in two row, and the middle 20 plants were scored for blast response. The mean of each family was used as raw data for QTL analysis. Lines developing asynchronously at the normal tillering or heading stages were excluded so that all data would reflect the same developmental stages of the plants. The BC4F2 segregation population were scored for leaf blast response at tillering stage in 2013. The most seriously diseased leaf of the top two or three new leaves was scored for each plant at each stage using the rating scale of Bonman et al. (1986), where 0 = no evidence of infection; 1 = brown specks smaller than 0.5 mm in diameter, no sporulation; 2 = brown specks about 0.5–1.0 mm in diameter, no sporulation; 3 = roundish to elliptical lesions, 1–3 mm in diameter, grey centre surrounded by brown margins, lesions capable of sporulation; 4 = typical spindle-shaped blast lesions capable of sporulation,3 mm or longer; 5 = lesions as in 4 but about half of one to two leaf blades killed by coalescence of lesions. Reaction types 0, 1, 2 and 3 were considered resistant, and 4 and 5 as susceptible (Das et al. 2012). Neck blast severity was recorded as a percentage of infection on the neck of rice panicle at physiological maturity stage. The number of panicles showing symptoms of neck blast was expressed as percent infection. Reaction types 0–25% were considered resistant, and 26%–100% as susceptible (Gao et al. 2008; IRRI 2002). To induce infection by the pathogen, diseased straw collected during the previous year was evenly dispersed in each plot and the highly susceptible variety; CO39, was planted on both sides of each row and around the experimental population. Field management essentially followed normal agricultural practices with the exception of no use of bactericides.

DNA Markers

Among 1032 simple sequence repeat (SSR) markers, 182 were polymorphic between Jin23B and CR071, and 161 were polymorphic between Jin23B and QingGuAi3, the level of polymorphism were 17.63% and 15.60%, respectively. A total of 145 and 113 polymorphic markers covering the whole rice genome were used to develop the genetic linkage map of Jin23B/CR071 and Jin23B/QingGuAi3 population. The RM marker series were searched in the available rice genomic database (http://www.gramene.org). Insertion/deletion markers were designed based on the references maps of Nipponbare and 9311. Genomic DNA was isolated from leaf tissues using the CTAB method. The SSR assay was performed with 4% urea polyacrylamide gels migration and silver staining as reported by Panaud et al. (1996).

Genetic Map Construction and QTL Analysis

A genetic linkage map was constructed using the Kosambi mapping function of MapMaker/Exp3.0 program (Lincoln et al. 1992). QTL analysis was performed by composite interval mapping (CIM) method using Windows QTL Cartographer 2.5 software (Wang et al. 2007) with a logarithm of odds (LOD) threshold of 2.5. Genotypes of the BC3F1 population were determined using SSR markers. The resistance score and genotype of each plant in the BC3F1 population were used for QTL analysis. For QTL detection of the BC3F2 population, the mean of each BC3F2 family was used as the row value and the genotypes of the BC3F1 plants were used as the genotypes of the BC3F2 families. Correlation analysis between six observation times in 2011 and in 2012 were examined by the Pearson correlation coefficient test. The resistance score of each plant in the BC3F1 population were used for correlation analysis. The mean of each BC3F2 family were used as the row value for correlation analysis. Data analyses were performed using Microsoft Excel 2003 or SPSS 17.0.

Results

SSR Assay of Two Backcross Population

Two backcross populations derived from the cross between Jin23B and CR071 and between Jin23B and QingGuAi3 contained 239 and 237 plants, respectively. Genomic DNA was isolated from young leaves of seeding from each plant using the CTAB method. A total of 145 polymorphic SSR markers covering the whole rice genome between Jin23B and CR071, and 113 polymorphic SSR markers between Jin23B and QingGuAi3 were used to detect the genotype of each plant. Theoretically, 87.5% of the markers are Jin23B homozygous genotype of each individual plant in BC3F1 population. In the Jin23B/CR071 background population, the marker ratio of Jin23B homozygous genotype of each plant were from 52.41% to 99.31%, most plants with a marker ratio in 90–100% (Fig. S1). In the Jin23B/QingGuAi3 background population, the marker ratio of Jin23B homozygous genotype of each plant were from 51.33% to 94.69%, most plants with a marker ratio in 80–90% (Fig. S1).

Measurements and Relationship of the Traits

The receptor parent Jin23B is an indica variety with susceptible performance to rice blast, and the donor parents CR071 and QingGuAi3 with resistance performance to rice blast. The leaf blast resistance score of Jin23B were 4.17 and 4.11 at tillering stage, and 4.22 and 4.19 at heading stage in 2011 and 2012 respectively (Table 1). The neck blast resistance of Jin23B were 91.7% and 93.7% in 2011 and 2012 respectively (Table 1). The leaf blast resistance score of CR071 and QingGuAi3 were 0.83 and 1.06 at tillering stage in 2011, and 0.97 and 1.11 at tillering stage in 2012 (Table 1). The leaf blast resistance score of CR071 and QingGuAi3 were 1.00 and 1.14 at heading stage in 2011, and 1.00 and 1.19 at heading stage in 2012 (Table 1). For neck blast resistance, CR071 and QingGuAi3 were 3.33% and 6.67% in 2011, and 4.67% and 8.33% in 2012 (Table 1). The resistance score between CR071 and Jin23B, QingGuAi3 and Jin23B were significant different at the corresponding measurement stages (Table 1). The resistance control BL6 and susceptible control CO39 had leaf blast scores of 1.20 and 4.60 at tillering stage and 1.30 and 5.00 at heading stage in 2011. And those for neck blast of BL6 and CO39 at maturation stage were 10.11% and 96.53% in 2011, and 12.10% and 100% in 2012.

The distributions of lesion scores as measures of blast response at tillering and heading stages for leaf blast and maturation stage for neck blast for the BC3F1 population in 2011 and BC3F2 population in 2012 are shown in Fig. 2. There was transgressive segregation in both directions for all traits. The Pearson correlation coefficients showed significant correlation (p < 0.01) between all six traits in both years (Table S1; Table S2). Blast resistance of the BC3F1 population at the tillering and heading stages in 2011 had a remarkable positive relationship with blast resistance of the BC3F2 population at the heading and maturation stages in 2012 (p < 0.01). Resistance during different stages also exhibited significant relationships (p < 0.01). Leaf blast at the tillering and heading stages and neck blast at the maturation stage were significantly correlated with each other, so we were able to predict the neck blast response level according to the leaf blast response at tillering under natural condition.

Frequency distribution of blast resistance of the Jin23B/CR071 (a, b, c) and Jin23B/QingGuAi3 (d, e f) population in 2011 and 2012. 11RT and 12RT, leaf blast resistance at tillering stage in 2011 and 2012. 11RH and 12RH, leaf blast resistance at heading stage in 2011 and 2012. 11RN and 12RN, neck blast resistance at maturation stage in 2011 and 2012. Blue pillar and green pillar indicate the frequency of BC3F1 and BC3F2 population, respectively

QTL Mapping for Blast Resistance in Jin23B/CR071 Population

A total of 16 QTLs for blast resistance were identified on chromosomes 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 7, 8, 11 and 12 in the Jin23B/CR071 population in 2 years (Table 2; Fig. 3). The phenotypic variance explained by each QTL ranged from 3.50% to 34.08%.

Distribution of QTLs for blast resistance in the Jin23B/CR071 population on the genetic linkage map. 11RT and 12RT, leaf blast resistance at tillering stage in 2011 and 2012. 11RH and 12RH, leaf blast resistance at heading stage in 2011 and 2012. 11RN and 12RN, neck blast resistance at maturation stage in 2011 and 2012

For leaf blast resistance at tillering stage, nine QTLs were detected on chromosome 1, 2, 3, 6, 7, 8 and 12 (Table 2; Fig. 3). Among them, four QTLs, qBR2–1, qBR3–3, qBR6 and qBR12 were detected in both year, five QTLs, qBR1, qBR2–2, qBR2–3, qBR7–1 and qBR8 were detected only in 2012 (Table 2; Fig. 3). The QTLs flanked by SR49 and RM426 on chromosome 3, qBR3–3, was detected in both year and explained 25.42% of the phenotypic variation in 2011 and 34.08% of the phenotypic variation in 2012. A QTLs, qBR6, located between RM539 and R19951 on chromosome 6, was also detected in 2 years and explained 8.89% and 20.40% of the phenotypic variation, respectively. Two QTLs, qBR2–1 and qBR12, were located flanked by RM236-RM451 on chromosome 2, and RM179-YP6213 on chromosome 12, respectively. qBR2–1 was detected in both years and accounted for 6.64% and 8.17% of the phenotypic variation, respectively. Whereas qBR12 was detected in both year and accounted for 4.25% and 4.48% of the phenotypic variation.

For leaf blast resistance at heading stage, eight QTLs were detected on chromosome 1, 2, 3, 6, 8 and 12 (Table 2; Fig. 3), and all the QTLs were detected in both year. These QTLs explained the phenotypic variance ranged from 3.90% to 25.83% in 2011, and from 3.50% to 31.33% in 2012. Among them, the QTL, qBR3–3, flanked by SR49 and RM426 on chromosome 3, have the largest effect which explained 25.83% of the phenotypic variation in 2011 and 31.33% of the phenotypic variation in 2012.

For neck blast resistance at maturation stage, eleven QTLs were detected on chromosome 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8 and 11 (Table 2; Fig. 3). Among them, seven QTLs, qBR1, qBR3–1, qBR7–1, qBR7–2, qBR11–1, qBR11–2 and qBR11–3 were detected in both year, four QTLs, qBR2–3, qBR3–2, qBR4 and qBR8 were detected only in 2011 (Table 2; Fig. 3). These QTLs explained the phenotypic variance ranged from 3.91% to 28.48% in 2011, and from 7.02% to 26.19% in 2012. A QTL, qBR7–1, located between RM501 and RM542 on chromosome 7, explained 28.48% of the phenotypic variation, which have the largest effect in 2011. Whereas the QTL qBR11–1, located between RM181 and RM120 on chromosome 11, accounted for 26.19% of the phenotypic variation, which have the largest effect in 2012.

Among the sixteen QTLs in the Jin23B/CR071 population, the gene effect of fifteen QTLs come from donor parent CR071, in contrast, the gene effect of qBR1 come from Jin23B. In the population, some plants have a transgressive segregation. Through analysis, we found that the QTL qBR1 has a negative effect. So the gene effect of qBR1 is from Jin23B, not CR071. The QTLs, qBR1, flanked by RM237 and RM486 on chromosome 1, was detected in both year for leaf blast and neck blast resistance and explained phenotypic variations of 6.09% in 12RT, 7.99% in 11RH, 7.25% in 12RH, 8.12% in 11RN and 9.48% in 12RN, respectively (Table 2). Two QTLs qBR2–3 and qBR8 were detected in both year for leaf blast and neck blast resistance; five QTLs qBR2–1, qBR2–2, qBR3–3, qBR6 and qBR12 were detected in both year for leaf blast at tillering and heading stages; eight QTLs qBR3–1, qBR3–2, qBR4, qBR7–1, qBR7–2, qBR11–1, qBR11–2 and qBR11–3 were detected only for neck blast in maturation stage.

QTL Mapping for Blast Resistance in Jin23B/QingGuAi3 Population

A total of 13 QTLs for blast resistance were identified on chromosomes 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 7, 8, 11 and 12 in the Jin23B/QingGuAi3 population in 2 years (Table 3; Fig. 4). The phenotypic variance explained by each QTL ranged from 2.42% to 28.95%.

Distribution of QTLs for blast resistance in the Jin23B/QingGuAi3 population on the genetic linkage map. 11RT and 12RT, leaf blast resistance at tillering stage in 2011 and 2012. 11RH and 12RH, leaf blast resistance at heading stage in 2011 and 2012. 11RN and 12RN, neck blast resistance at maturation stage in 2011 and 2012

For leaf blast resistance at tillering stage, five QTLs were detected on chromosome 1, 6, 7 and 11 (Table 3; Fig. 4). Among them, two QTLs, qBR6 and qBR7–1 were detected in both year, three QTLs, qBR1–1, qBR11–1 and qBR11–2 were detected only in 1 year (Table 3; Fig. 4). The QTL flanked by L6ID3F and ZH6111 on chromosome 6, qBR6, was detected in both year and explained 24.93% of the phenotypic variation in 2011 and 19.91% of the phenotypic variation in 2012. The QTL, qBR7–1, flanked by RM214 and RM5543 on chromosome 7 was detected in both years and accounted for 8.87% and 4.12% of the phenotypic variation, respectively. Whereas qBR11–1 and qBR11–2 were detected only in 1 year and accounted for 6.57% and 5.49% of the phenotypic variation.

For leaf blast resistance at heading stage, four QTLs were detected on chromosome 4, 6, 7 and 11 (Table 3; Fig. 4). Two QTLs, qBR6 and qBR7–1, were detected in both year and the QTLs explained the phenotypic variance were 36.48% and 16.47% in 2011, respectively, and 25.27% and 26.31% in 2012, respectively. Two QTL, qBR4–2 and qBR11–1, were located flanked by RM241-RM317 on chromosome 4, and RM229-RM547 on chromosome 11, respectively. The QTLs qBR4–2 and qBR11–1 were detected only in 2012 and accounted for 2.51% and 2.42% of the phenotypic variation, respectively.

For neck blast resistance at maturation stage, ten QTLs were detected on chromosome 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 7 and 12 (Table 3; Fig. 4). Among them, four QTLs, qBR4–1, qBR4–2, qBR6 and qBR7–1 were detected in both year, and explained the phenotypic variance were 12.31%, 8.82%, 31.91% and 27.94%, respectively, in 2011, and were 18.47%, 16.92%, 28.95% and 18.71%, respectively, in 2012. Six QTLs, qBR1–2, qBR2, qBR3, qBR7–2, qBR8 and qBR12 were detected only in 1 year (Table 3; Fig. 4), and explained the phenotypic variance were 8.55%, 8.92%, 12.72%, 3.43%, 18.89% and 9.58%, respectively.

Among the thirteen QTLs in the Jin23B/QingGuAi3 population, the gene effect of twelve QTLs come from donor parent QingGuAi3, in contrast, the gene effect of qBR12 come from Jin23B. The QTLs, qBR12, flanked by RM5927 and RM6296 on chromosome 12, was detected only in 2012 at maturation stage and explained phenotypic variations of 9.58% (Table 3). Three QTLs, qBR4–2, qBR6 and qBR7–1 were detected in both year at tillering and heading stages for leaf blast and maturation stage for neck blast; three QTL, qBR1–1, qBR11–1 and qBR11–2, were detected for leaf blast at tillering or heading stages; five QTLs, qBR1–2, qBR2, qBR3, qBR4–1 and qBR7–2 were detected for neck blast at maturation stage.

Validate the Genetic Effect of qBR3–3 and qBR6 from CR071 and qBR6 and qBR7–1 from QingGuAi3

The BC4F2 segregation population of qBR3–3 and qBR6 from CR071 and qBR6 and qBR7–1 from QingGuAi3 were used to confirm the genetic effect of these QTLs. The qBR3–3 and qBR6 loci from CR071 increased blast resistance by 1.13 and 1.43, respectively, on leaf blast at tillering stage in 2013 (Fig. 5). The qBR6 and qBR7–1 loci from QingGuAi3 increased blast resistance by 1.70 and 0.83, respectively, on leaf blast at tillering stage in 2013 (Fig. 5).

Discussion

QTL mapping using advanced backcross population was proposed as an effective molecular breeding technique for incorporating valuable genes from exotic sources into an adapted background (Eizenga et al. 2013; Tanksley and Nelson 1996). With this method, QTL from the donor parents are detected by backcrossing with the adapted parent to eliminate most of the unwanted genes from the donor parent. In addition, using advanced backcross population can accelerate the crop improvement process because near-isogenic lines containing the desired QTL (genes) from the donor in the background of the recurrent parent can be selected from the advanced backcross population. Several studies have been performed to identify QTLs in advanced backcrossing. For example, Thomson et al. (2003) mapped quantitative trait loci for yield, yield components and morphological traits in rice using a BC2F1 and BC2F2 population by composite interval mapping and Windows QTL Cartographer 1.21. And Eizenga et al. (2013) mapped sheath blight and blast quantitative trait loci in two different advanced backcross populations. In our study, we developed two advanced backcross population with the objective of introgression of useful resistance genes from CR071 and QingGuAi3 into Jin23B. Using this strategy, we mapped 16 blast resistance QTLs from the Jin23B/CR071 population and 13 blast resistance QTLs from the Jin23B/QingGuAi3 population. We also obtained maintainer lines resistant to blast in the background of Jin23B, which can be used for rice blast resistance breeding.

To date, over 100 blast resistant genes or QTLs have been identified (Su et al. 2015; Vasudevan et al. 2016; Xiao et al. 2017; Zheng et al. 2016). Among them, 37 genes have been cloned (Wang et al. 2017; Wang et al. 2019; Zhao et al. 2018). Many of these resistance genes are clustered on rice chromosomes 6, 11 and 12. Notably, at least 11 resistance genes—including Pi2, Pi9, Piz, Pizt, Pigm, Pi22, Pi25, Pi26, Pi40, Pi42 and Pi50—are concentrated in the short-arm region near the centromere of chromosome 6. In this study, a QTL qBR6 located between RM539 and R19951 in the Jin23B/CR071 population have a significant resistance to rice blast in both 2 years. When we further compared the position of this region to previous studies, we found that it contained Pi2, Pi9, Pigm, Pizt and Pi50, which are cloned blast resistance genes (Deng et al. 2017; Qu et al. 2006; Su et al. 2015; Zhou et al. 2006). QTL qBR6 located between L6ID3F and ZH6111 in the Jin23B/QingGuAi3 population was also overlapped the Pi2/Pi9 gene cluster on chromosome 6. Thus, qBR6 identified in two population may be the allele of Pi2, Pi9, Pigm, Pizt or Pi50.

QTLs qBR1 was located between RM237 and RM486 on chromosome 1 in the Jin23B/CR071 population, and the QTL qBR1–2 was located between RM297 and RM486 in the Jin23B/QingGuAi3 population, in this region, blast resistance gene Pi37, Pish and Pi35(t) had previously been reported (Lin et al. 2007; Nguyen et al. 2006; Takahashi et al. 2010). The blast resistance gene Pi37 and Pish have been cloned, which encode a NBS-LRR protein. Pi35(t) was identified in a QTL analysis of a population derived from the Japonica rice cultivar Hokkai 188 and the Indica rice cultivar Danghang-Shali. The resistance conferred by Pi35(t) to M. oryzae is classified as partial resistance (quantitative) rather than true resistance (qualitative). It is possible that qBR1 from Jin23B/CR071 population and qBR1–2 from Jin23B/QingGuAi3 population are allelic to either Pi37, Pish or Pi35(t). QTLs qBR2–3 located between RM530 and RM213 on chromosome 2 in the Jin23B/CR071 population, was close to the cloned gene Pib (Wang et al. 1999). The neck blast resistance QTLs, qBR11–1, was located between RM21 and RM590 on chromosome 11 in the Jin23B/CR071 population, in this region, blast resistance gene Pikm, Pik-h and Pik-p had previously been reported (Ashikawa et al. 2008; Yuan et al. 2011; Zhai et al. 2014). It is possible that qBR11–1 is allelic to either Pikm, Pik-h or Pik-p. In the Jin23B/QingGuAi3 population, QTL qBR7–1 located between RM214 and RM5543 on chromosome 7 have a significant resistance to rice blast, in this region few gene have been reported, thus qBR7–1 may be a new gene.

Rice cultivars with durable blast resistance have been recognized in several production systems. The durable resistance of these cultivars is associated with polygenic partial resistance that shows no evidence of race specificity. This partial resistance is expressed as fewer and smaller lesions on the leaf blade but latent period does not appear to be an important component. Many blast resistant varieties with single resistance genes lose resistance after a few years; that is, they have or had nondurable resistance (Babujee and Gnanamanickam 2000). Varieties with durable resistance may contain more than one resistance gene (Zhu et al. 2012). Many studies have been performed to pyramid resistances gene into rice varieties. Hittalmani et al. (2000) pyramided three blast resistance genes Pi1, Piz-5 and Pita into rice variety CO39 and Jiang et al. (2012) pyramided three blast resistance genes Pi1, Pi2 and D12 into rice variety Jin23B. Their results confirmed that pyramiding of blast resistance genes is an effective way to develop highly resistant varieties. In our study, the donor parent CR071 and QingGuAi3 have a high level and durable resistance to blast over past decades, and have been used as donor parent for blast resistance in breeding in China. In the study, two advanced backcross population were constructed for analyses the genetic mechanism of blast resistance in CR071 and QingGuAi3, and major and minor blast resistance QTLs were identified in the donor parents. QTL effect analyses suggested that major and minor QTLs interaction is the genetic basis for durable blast resistance for CR071 and QingGuAi3 in the past decade in Wuling mountain area in China.

Conclusions

Overall, the mapping results showed that sixteen blast resistance QTLs were identified in the Jin23B/CR071 backcross population, in which, QTLs qBR1, qBR2–3 and qBR8 were detected in both year for leaf blast and neck blast resistance; five QTLs qBR2–1, qBR2–2, qBR3–3, qBR6 and qBR12 were detected in both year for leaf blast at tillering and heading stages; eight QTLs qBR3–1, qBR3–2, qBR4, qBR7–1, qBR7–2, qBR11–1, qBR11–2 and qBR11–3 were detected for neck blast in maturation stage. Thirteen blast resistance QTLs were identified in Jin23B/QingGuAi3 population, in which, three QTLs, qBR4–2, qBR6 and qBR7–1 were detected in both year at tillering and heading stages for leaf blast and maturation stage for neck blast; three QTL, qBR1–1, qBR11–1 and qBR11–2, were detected for leaf blast at tillering or heading stages; six QTLs, qBR1–2, qBR2, qBR3, qBR4–1, qBR7–2 and qBR12 were detected for neck blast at maturation stage.

Abbreviations

- 11RT:

-

Leaf blast resistance at tillering stage in 2011

- 11RH:

-

Leaf blast resistance at heading stage in 2011

- 11RN:

-

Neck blast resistance at maturation stage in 2011. 12RT: Leaf blast resistance at tillering stage in 2012

- 12RH:

-

Leaf blast resistance at heading stage in 2012

- 12RN:

-

Neck blast resistance at maturation stage in 2012

- CIM method:

-

Composite interval mapping method

- NBS-LRR gene:

-

Nucleotide-binding site leucine-rich repeat gene

- QTLs:

-

Quantitative trait loci

- R gene:

-

Resistance gene

- SSR:

-

Simple sequence repeat

References

Ashikawa I, Hayashi N, Yamane H, Kanamori H, Wu JZ, Matsumoto T, Ono K, Yano M (2008) Two adjacent nucleotide-binding site-leucine-rich repeat class genes are required to confer Pikm-specific rice blast resistance. Genetics 180(4):2267

Babujee L, Gnanamanickam S (2000) Molecular tools for characterization of rice blast pathogen, Magnaporthe grisea, population and molecular marker-assisted breeding for disease resistance. Curr Sci 78:24–257

Bonman JM (1992) Durable resistance to rice blast disease-environmental influences. Euphytica 63:115–123

Bonman JM, De Dios TIV, Khin MM (1986) Physiologic specialization of Pyricularia oryzae in the Philippines. Plant Dis 70:767–769

Bryan GT, Wu KS, Farrall L, Jia YL, Hershey HP, McAdams SA, Faulk KN, Donaldson GK, Tarchini R, Valent B (2000) A single amino acid difference distinguishes resistant and susceptible alleles of the rice blast resistance gene Pi-ta. Plant Cell 12:2033–2045

Das A, Soubam D, Singh PK, Thakur S, Singh NK, Sharma TR (2012) A novel blast resistance gene, Pi54rh cloned from wild species of rice, Oryza rhizomatis confers broad spectrum resistance to Magnaporthe oryzae. Funct Integr Genom 12:215–228

Deng Y, Zhai K, Xie Z, Yang D, Zhu X, Liu J, Wang X, Qin P, Yang Y, Zhang G, Li Q, Zhang J, Wu S, Milazzo J, Mao B, Wang E, Xie H, Tharreau D, He Z (2017) Epigenetic regulation of antagonistic receptors confers rice blast resistance with yield balance. Science 355:962–965

Eizenga GC, Prasad B, Jackson AK, Jia MH (2013) Identification of rice sheath blight and blast quantitative trait loci in two different O. sativa/O. nivara advanced backcross populations. Mol Breed 31(4):889–907

Fukuoka S, Saka N, Koga H, Ono K, Shimizu T, Ebana K, Hayashi N, Takahashi A, Hirochika H, Okuno K, Yano M (2009) Loss of function of a proline-containing protein confers durable disease resistance in rice. Science 325:998–1001

Gao GJ, Li GJ, Bao L, He YQ (2008) Genetic analysis of rice blast resistance and identification of resistance genes throughout all stages in rice. Mol Plant Breed 6(5):825–829 (In Chinese with English abstract)

Hayashi N, Ando I, Imbe T (1998) Identification of a new resistance gene to a Chinese blast fungus isolate in the Japanese rice cultivar Aichi Asahi. Phytopathology 88(8):822–827

Hittalmani S, Parco A, Mew TV, Zeigler RS, Huang N (2000) Fine mapping and DNA marker-assisted pyramiding of the three major genes for blast resistance in rice. Theor Appl Genet 100:1121–1128

Hua LX, Wu JZ, Chen CX, Wu WH, He XY, Lin F, Wang L, Ashikawa I, Matsumoto T, Wang L, Pan QH (2012) The isolation of Pi1, an allele at the Pik locus which confers broad spectrum resistance to rice blast. Theor Appl Genet 125(5):1047–1055

Imbe T, Ora S, Yanoria MJT, Tsunematsu H (1997) A new gene for blast resistance in rice cultivar, IR24. Rice Genet Newsl 14:60–62

IRRI (2002) Standard evaluation system for rice (SES). International Rice Research Institute, Los Banos

Jiang HC, Feng YT, Bao L, Li X, Gao GJ, Zhang QL, Xiao JH, Xu CG, He YQ (2012) Improving blast resistance of Jin23B and its hybrid rice by marker-assisted gene pyramiding. Mol Breed 30:1679–1688

Jones JD, Dangl JL (2006) The plant immune system. Nature 444:323–239

Kou Y, Wang S (2010) Broad-spectrum and durability: understanding of quantitative disease resistance. Curr Opin Plant Biol 13:181–185

Li YB, Wu CJ, Jiang GH, Wang LQ, He YQ (2007) Dynamic analyses of rice blast resistance for the assessment of genetic and environmental effects. Plant Breed 126:541–547

Li YB, Wu CJ, Xing YZ, Chen HL, He YQ (2011) Dynamic QTL analysis for rice blast resistance under natural infection conditions. Aust J Crop Sci 2:73–82

Lin F, Chen S, Que ZQ, Wang L, Liu XQ, Pan QH (2007) The blast resistance gene Pi37 encodes a nucleotide binding site leucine-rich repeat protein and is a member of a resistance gene cluster on rice chromosome 1. Genetics 177(3):1871

Lincoln SE, Daly MJ, Lander ES (1992) Constructing genetic maps with MapMaker/EXP3.0

Liu WD, Wang GL (2016) Plant innate immunity in rice: a defense against pathogen infection. Natl Sci Rev 3:295–308

Nguyen TTT, Koizumi S, La TN, Zenbayashi KS, Ashizawa T, Yasuda N, Imazaki I, Miyasaka A (2006) Pi35(t), a new gene conferring partial resistance to leaf blast in the rice cultivar Hokkai 188. Theor Appl Genet 113:697–704

Pan QH, Wang L, Tanisaka T, Ikehashi H (1998) Allelism of rice blast resistance genes in two Chinese rice cultivars, and identification of two new resistance genes. Plant Pathol 47(2):165–170

Panaud O, Chen X, Mccouch SR (1996) Development of microsatellite markers and characterization of simple sequence length polymorphism (SSLP) in rice (Oryza sativa L.). Mol Gen Genet 252(5):597–607

Qu SH, Liu GF, Zhou B, Bellizzi M, Zeng LR, Dai LY, Han B, Wang GL (2006) The broad-spectrum blast resistance gene Pi9 encodes a nucleotide-binding site-leucine-rich repeat protein and is a member of a multigene family in rice. Genetics 172:1901–1914

Sallaud C, Lorieux M, Roumen E, Tharreau D, Berruyer R, Svestasrani P, Garsmeur O, Ghesquiere A, Notteghem JL (2003) Identification of five new blast resistance genes in the highly blast-resistant rice variety IR64 using a QTL mapping strategy. Theor Appl Genet 106:794–803

Sharma TR, Rai AK, Gupta SK, Singh NK (2010) Broad-spectrum blast resistance gene Pi-kh cloned from rice line Tetep designated Pi54. J Plant Biochem Biotechnol 19(1):87–89

Su J, Wang WJ, Han JL, Chen S, Wang CY, Zeng LX, Feng AQ, Yang JY, Zhou B, Zhu XY (2015) Functional divergence of duplicated genes results in a novel blast resistance gene Pi50 at the Pi2/9 locus. Theor Appl Genet 128(11):2213–2225

Tabien E, Li Z, Patterson AH, Marchetti A, Stansel W, Pinson M (2002) Mapping QTLs for field resistance to the rice blast pathogen and evaluating their individual and combined utility in improved varieties. Theor Appl Genet 105:313–324

Takahashi A, Hayashi N, Miyao A, Hirochika H (2010) Unique features of the rice blast resistance Pish locus revealed by large scale retrotransposon-tagging. BMC Plant Biol 10(1):175–0

Tanksley SD, Nelson JC (1996) Advanced backcross QTL analysis: a method for the simultaneous discovery and transfer of valuable QTLs from unadapted germplasm into elite breeding lines. Theor Appl Genet 92:191–203

Thomson MJ, Tai TH, McClung AM, Lai XH, Hinga ME, Lobos KB, Xu Y, Martinez CP, McCouch SR (2003) Mapping quantitative trait loci for yield, yield components and morphological traits in an advanced backcross population between Oryza rufipogon and the Oryza sativa cultivar Jefferson. Theor Appl Genet 107:479–493

Vasudevan K, Gruissem W, Bhullar NK (2016) Corrigendum: identification of novel alleles of the rice blast resistance gene Pi54. Sci Rep 6(15678):17920

Wang GL, Mackill DJ, Bonman JM, McCouch SR, Champoux MC, Nelson RJ (1994) RFLP mapping of genes conferring complete and partial resistance to blast in a durably resistant rice cultivar. Genetics 136:1421–1434

Wang GL, Valent B (2017) Durable resistance to rice blast. Science 355(6328):906–907

Wang J, Liu X, Zhang A, Yulong Ren WFQ, Wang G, Xu Y, Lei CL, Zhu SS, Pan T, Wang YF, Zhang H, Wang F, Tan YQ, Wang YP, Jin X, Luo S, Zhou CL, Zhang X, Liu JL, Wang S, Meng LZ, Wang YH, Chen X, Lin QB, Zhang X, Guo XP, Cheng ZJ, Wang JL, Tian YL, Liu SJ, Jiang L, Wu CY, Wang ET, Zhou JM, Wang YF, Wang HY, Wan JM (2019) A cyclic nucleotide-gated channel mediates cytoplasmic calcium elevation and disease resistance in rice. Cell Res 29:820–831

Wang S, Basten CJ, Zeng ZB (2007) Windows QTL cartographer 2.5. Department of Statistics, North Carolina State University, Raleigh, NC

Wang ZX, Yano M, Yamanouchi U, Iwamoto M, Monna L, Hayasaka H, Katayose Y, Sasaki T (1999) The Pib gene for rice blast resistance belongs to the nucleotide binding and leucine-rich repeat class of plant disease resistance genes. Plant J 19(1):55–64

Wu JL, Fan YY, Li DB, Zheng KL, Leung H, Zhuang JY (2005) Genetic control of rice blast resistance in the durably resistant cultivar Gumei 2 against multiple isolates. Theor Appl Genet 111:50–56

Wu SQ, Long JS, Yan XM, Li RF (2001) Identification, screening and evaluation of durable resistant sources of rice blast. Hubei Agri Sci 1(18):44–45 (in Chinese)

Xiao N, Wu YY, Pan CH, Yu L, Chen Y, Liu GQ, Li YH, Zhang XX, Wang ZP, Dai ZY, Liang CZ, Li AH (2017) Improving of rice blast resistances in Japonica by pyramiding major R genes. Front Plant Sci 7:1918

Yuan B, Zhai C, Wang WJ, Zeng XS, Xu XK, Hu HQ, Lin F, Wang L, Pan QH (2011) The Pik-p resistance to Magnaporthe oryzae in rice is mediated by a pair of closely linked CC-NBS-LRR genes. Theor Appl Genet 122(5):1017–1028

Zhai C, Lin F, Dong Z, Dong ZQ, He XY, Yuan B, Zeng XS, Wang L, Pan QH (2011) The isolation and characterization of Pik, a rice blast resistance gene which emerged after rice domestication. New Phytol 189(1):321–334

Zhai C, Zhang Y, Yao N, Lin F, Liu Z, Dong ZQ, Wang L, Pan QH (2014) Function and interaction of the coupled genes responsible for Pik-h encoded rice blast resistance. PLoS One 9(6):e98067

Zhao HJ, Wang XY, Jia YL, Minkenberg B, Wheatley M, Fan J, Jia M, Famoso A, Edwards J, Wamishe Y, Valent B, Wang GL, Yang Y (2018) The rice blast resistance gene Ptr encodes an atypical protein required for broad-spectrum disease resistance. Nat Commun 9:2039

Zheng WJ, Wang Y, Wang LL, Ma ZB, Zhao JM, Wang P, Zhang LX, Liu ZH, Lu XC (2016) Genetic mapping and molecular marker development for Pi65(t), a novel broad-spectrum resistance gene to rice blast using next-generation sequencing. Theor Appl Genet 129(5):1035–1044

Zhou B, Qu SH, Liu GF, Dolan M, Sakai H, Lu GD, Bellizzi M, Wang GL (2006) The eight amino-acid differences within three leucine-rice repeats between Pi2 and Piz-t resistance proteins determine the resistance specificity to Magnaporthe grisea. Mol Plant Microbe In 11:1216–1228

Zhu XY, Chen S, Yang JY, Zhou SC, Zeng LX, Han JL, Su J, Wang L, Pan QH (2012) The identification of Pi50(t), a new member of the rice blast resistance Pi2/Pi9 multigene family. Theor Appl Genet 124:1295–1304

Acknowledgements

We are very grateful to Professor Taipin Duan in Enshi Academy of Agricultural Sciences for providing seeds for the donor parents of the blast resistance cultivars.

Availability of Data and Material

The data sets supporting the results of this article are included within the article and its supporting files.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from the National Program on R&D of Transgenic Plants (2016ZX08001002–002), the National Natural Science Foundation (91935303, 31801438) and the earmarked fund for the China Agriculture Research System (CARS− 01-03) of China.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

YH designed the experiments. HJ, YF, and LQ performed the experiments. GG and QZ helped with field management. HJ, YF and LQ analyzed the data. HJ and YH wrote the manuscript. All authors approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

Not applicable.

Consent for Publication

Not applicable.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional Files

Additional File 1.

Figure S1 Marker ratio of Jin23B homozygous genotype of each plant in two BC3F1 background population. a, marker ratio of Jin23B homozygous genotype of each plant in Jin23B/CR071 background population. b, marker ratio of Jin23B homozygous genotype of each plant in Jin23B/QingGuAi3 background population.

Additional File 2.

Table S1 The correlation between six traits in Jin23B/CR071 background population

Additional File 3.

Table S2 The correlation detection between six traits in Jin23B/QingGuAi3 background population

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Jiang, H., Feng, Y., Qiu, L. et al. Identification of Blast Resistance QTLs Based on Two Advanced Backcross Populations in Rice. Rice 13, 31 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12284-020-00392-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12284-020-00392-6