Abstract

Assessing hemodynamics, especially central venous pressure (CVP), is essential in heart failure (HF). Right heart catheterization (RHC) is the gold-standard, but non-invasive methods are also needed. However, the role of 2-dimensional echocardiography (2DE) remains uncertain, and 3-dimensional echocardiography (3DE) is not always available. This study investigated standardized and breathing-corrected assessment of inferior vena cava (IVC) volume using echocardiography (2DE and 3DE) versus CVP determined invasively using RHC. Sixty consecutive HF patients were included (82% male, age 54 ± 11 years, New York Heart Association class 2.23 ± 0.8, ejection fraction 46 ± 18.4%, brain natriuretic peptide 696.93 ± 773.53 pg/mL). All patients underwent Swan-Ganz RHC followed by 2DE and 3DE, and IVC volume assessment. On 2DE, mean IVC size was 18.3 ± 5.5 mm and 13.8 ± 6 mm in the largest deflection and shortest distention, respectively. Mean CVP from RHC was 9.3 ± 5.3 mmHg. Neither 2DE nor 3DE showed acceptable correlation with invasively measured CVP; IVC volume acquisition showed optimal correlation with RHC CVP (0.64; 95% confidence interval 0.46–0.77), with better correlation when mitral valve early diastole E wave and right ventricular end-diastolic diameter were added. Using a CVP cut-point of 10 mmHg, receiver operating characteristic curve showed true positivity (specificity) of 0.90 and sensitivity of 62% for predicting CVP. A validation study confirmed these findings and verified the high predictive value of IVC volume assessment. Neither 2DE nor 3DE alone can reliably mirror CVP, but IVC volume acquisition using echocardiography allows non-invasive and adequate approximation of CVP. Correlation with invasively measured pressure was strongest when CVP is > 10 mmHg.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Heart failure (HF) prevalence is increasing, with a progressive disease course, poor prognosis and impaired quality of life [1]. Guiding therapy in individual HF patients remains challenging, and hemodynamics and filling pressures play a major role, particularly in predicting rehospitalization and mortality [2]. Assessing hemodynamic parameters, including central venous pressure (CVP), is essential in HF for both diagnostics and therapy guidance, but there is currently no non-invasive, quick, and easy-to-use technique for reliable measurement of CVP.

CVP has been shown to be an independent predictor of cardiac rehospitalization in patients with acute decompensated HF presenting to an emergency room [3]. Volume overload represents the leading cause of HF decompensation [4], but simple and reliable methods for determining volume overload in HF are lacking [5]. Established clinical appraisal of venous congestion, such as jugular vein distension is known to be unreliable and differs between observers [5, 6], although venous congestion has been demonstrated to be the leading predictor of organ injury and death [7].

Today, invasive assessment of CVP remains the only reliable approach to identify volume overload in HF, but the “gold-standard” Swan-Ganz catheter right heart catheterization (RHC) is costly, uncomfortable for patients, and associated with procedural risks such as pneumothorax, cardiac arrhythmia, bleeding, infection, nerve or vessel injury [8]. Therefore, there is a need for a non-invasive alternative but none is currently available. Most clinicians take the approach of estimating CVP using two-dimensional echocardiography (2DE) to estimate inferior vena cava (IVC) size in the subcostal view [9]. However, interobserver variability is high and agreement with invasive measurement is poor [10]. This is due to the often elliptical and irregular shape of the IVC and the variegating angle in which the ultrasound window depicts the vessel, making it impossible to capture the real dimension of the IVC with any two-dimensional approach [9]. It has been suggested that three-dimensional echocardiography (3DE) has the potential to capture CVP, but time consuming vessel area registration and complex calculations of a collapsibility and eccentricity index are needed to achieve reproducible and accurate measurements, making this approach impractical in daily clinical routine [9]. Cross-section measurements of IVC short and long axis were found to have potential for estimating CVP, but this was mainly limited to the ability to detect CVP of < 10 versus ≥ 10 mmHg [11].

Due to the high clinical impact and importance of accurate CVP measurement for determining prognosis, guiding HF therapy, preventing secondary organ damage, and evaluating suitability for heart transplantation, this study investigated the best possible approach for ultrasound-based non-invasive CVP measurements using echocardiography compared with RHC, including relevant confounders.

Methods

Study design

This prospective, single-center, observational study included consecutive HF patients from an academic medical center in Bad Oeynhausen, Germany (Herz- und Diabeteszentrum Nordrhein-Westfalen, Ruhr-University Bochum). The trial was registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT03231774).

Study population

Eligible patients were scheduled for routine HF check-up and underwent routinely planned echocardiography and RHC. Exclusion criteria were age < 18 years, chronic kidney disease requiring dialysis, and the presence of an implanted total artificial heart device.

Right heart cardiac catheterization

Swan-Ganz RHC was performed in all study participants, immediately followed by echocardiography to ensure the same volume load for both examination methods. After setting-up routine monitoring (including ECG, non-invasive blood pressure and pulse oximetry), pulmonary artery catheterization (Edwards Lifesciences, Irvine, CA, USA) was performed by introduction into right internal jugular vein by experienced operators only. The Swan-Ganz pulmonary artery catheter was then advanced to first determine CVP, followed by other right heart pressure values.

Two-dimensional echocardiography

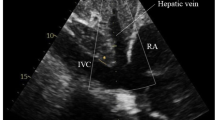

Comprehensive transthoracic echocardiographic examinations were performed using Philips EPIQ 7 G ultrasound system (Philips Healthcare, Koninklijke Philips N.V., Amsterdam, The Netherlands) using variable-frequency 1.0 to 5 MHz sector transducers (Philips X5-1- transducer). All echocardiographic recording included assessment of both the left and right heart. Including established standard measures, we assessed left ventricular end-diastolic volume, left ventricular end-systolic volume and left ventricular ejection fraction, using standardized Simpson’s method in both four and two chamber view. Additional collected parameters contained left atrial volume, pulsed Doppler transmitral flow profiles, pulsed wave Doppler placed in the left ventricular outflow tract, and tissue Doppler Imaging on the mitral annulus. Right heart function was assessed using right ventricular end-diastolic volume, tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion, and fractional area change of the right ventricle. The velocity flow profile in hepatic veins was measured by pulsed wave Doppler from the subcostal view and the pulsed wave Doppler flow profile of the upper right pulmonary vein was recorded. Strain analysis was performed and the Myocardial Performance Index (Tei-Index) was calculated. The size of the IVC was determined with the patient in the supine position using 2DE images from the subxyphoidal view. The breathing-corrected diameter was measured perpendicular to the long-axis of the IVC, proximal to the junction of the hepatic veins, 2.0 cm proximal to the ostium of the right atrium, assessing IVC volume as largest deflection and shortest distention.

Three-dimensional echocardiography

Single full-volume 3DE loop data were acquired using a subxyphoidal view with the patient in a supine position. 3DE full-volume images of standardized breathing-corrected sounding IVC were recorded, placed approximately 2.0 cm (0.79 inches) proximal to the ostium of the right atrium and perpendicular to the long-axis reference of the IVC. Digital cross-sectional image reconstruction was done using available software (Philips QLAB 10, QLAB Ultrasound Cardiac Analysis, Koninklijke Philips N.V., Amsterdam, The Netherlands) for cardiac 3D quantification. IVC cross-sectional images were scaled into a vertical diameter and in a second diameter perpendicular to the vertical diameter. All measurements were compiled for their largest and smallest deflection. In addition, IVC area was quantified in the cross-sectional images to picture frequent irregular IVC morphology. Schematic presentation of exemplary echocardiographic examination with ultrasound images in cross-sectional and longitudinal-sectional view of IVC is shown in Fig. 1.

Schematic visualization of echocardiography technique used in this study. This figure illustrates the standardized consistent measurement of inferior vena cava (IVC) and vena cava inferior volume, defined as the product of largest deflection and shortest distention, used in this study. Transducer placed in predefined standardized subxyphoidal position. Patient in supine position and IVC diameters are measured, breathing corrected, perpendicular to IVC long-axis, proximal to the junction of the hepatic veins, 2.0 cm proximal to the ostium of the right atrium, assessing IVC volume as largest deflection and shortest distention

Statistical analysis

Firstly, the correlation between IVC measures and CVP was estimated. Then a first linear regression model was selected that could best predict CVP using IVC measures and demographic values (Model 1). 3DE was not available in all patients due to poor image quality; instead, IVC volume was assessed using orthogonal transducer locations. In the second phase, a large number of non-invasive routinely collected measures with the potential to improve the above prediction model were considered (Model 2). All measures for which data were available for at least 50/60 were considered to ensure that there were enough observations to imply a linear regression model. Next, stepwise selection-based analysis was performed, using the sufficient sample size of at least 50 observations and based on Akaike information criterion (AIC) and R-squared (R2) values. The models were always compared with the dataset including all complete cases for the comprehensive set of all variables under consideration. Variables for which there was a smaller dataset were considered for sensitivity analyses. The predictive model was then validated by randomly splitting the dataset into two equal parts, one to obtain regression parameters for the model and one to test the predictive values of the final model.

The predictive values of Model 2 were tested by considering the distribution of the difference between predicted values and observed values, and by using a CVP diagnostic threshold of 10 mmHg and obtaining the area under the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve. Analyses were performed using Stata 14 (StataCorp. 2015. Stata Statistical Software: Release 14. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP), plots were realized using Sigma- Plot 12.0 by Systat Software Inc.

Reproducibility

Echocardiography was performed by independent, blinded, experienced sonographers to exclude any examiner-dependent confounding. Moreover, both examiner groups for either echocardiography, as well as for Swan-Ganz catherization, were blinded from the results of the other group, to avoid influencing of any kind between the two methods. All software-based measurements were measured more than three times for each case, and those with if a deviation of > 5% were discarded.

Results

A total of 60 patients were screened and fulfilled inclusion criteria for study participation (Table 1). All patients underwent complete clinical assessment including Swan-Ganz RHC followed by immediate 2DE and 3DE (Philips EPIQ 7G) examination including inferior vena cava (Fig. 1). Echocardiographic characteristics and catheterization data are presented in Table 2. All patients were assessed using 2DE, but 3DE data from three patients had to be excluded for poor image quality. Our inter- and intra-observer variability with 8% and below 5%, was comparable to similar studies in the literature. The results of the correlation analysis are presented in Table 3, including sample size for each variable.

2DE CVP measurements did not show satisfactory correlation for CVP alone, but breathing-corrected IVC volume assessment showed some correlation with invasively measured CVP (R2 = 0.64). When adding supplementary patient characteristics to the predictive statistical model (e.g. weight, height and body mass index), the R2 value reached 0.47. Other 3DE and 2DE measurements were unsatisfactory, mainly due to limited image quality, reaching correlations with R2 values of around 0.5 only.

Results from the linear model for IVC volume are provided in Table 4. Our model enhancement practice for a fully-optimized prediction model resulted in addition of the established variables mitral valve early diastole E wave (MVED) and right ventricular end-diastolic diameter (RVEDD) to the first model. The new model had a R2 squared value of 0.66. The scatter plot of this linear prediction and its observed values of CVP are presented in Fig. 2, and show a regular distribution of the reading points around the correlation line in equality, suggesting good predictive value. Sensitivity analyses disclosed a CVP threshold of 10 mmHg to be most exact, which above all is clinically the utmost used value. When using a threshold for predicting CVP of 8 mmHg, sensitivity was 86%, specificity 74%, and a threshold for predicting CVP of 12 mmHg, sensitivity was 48%, specificity 97%.

Clinically most useful CVP cut-point of 10 mmHg resulted in an area under the ROC curve (Fig. 3) of 0.90 (95% confidence interval [CI] 0.81–0.98), with specificity of 90% and sensitivity of 62%. The sensitivity analysis showed that this prediction model could not be improved by any other additional variables. The positive predictive value is 81% and the negative predictive value is 78%.

Sensitivity of statistical model 2 for central venous pressure (CVP) prediction. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve for the predicted values from statistical model 2 and a CVP cut-point of 10 mmHg, under consideration of mitral valve early diastole E wave and right ventricular end-diastolic diameter. Area under the ROC curve (AUC): 0.90 (95% confidence interval 0.81–0.98)

The broad variety of vena cava shapes identified are depicted in Fig. 4, illustrating the challenge of standardized assessment of vena cava size.

Inferior vena cava volume calculation—Inferior vena cava images including vectors. a1 Example of a smaller roundish-shaped inferior vena cava with orthogonal vectors for volume. a2 Example of a congested roundish-shaped inferior vena cava with orthogonal vectors for volume calculation. b1 Example of a decongested ellipsoid-shaped inferior vena cava with orthogonal vectors for volume calculation. b2 Example of a congested ellipsoid-shaped inferior vena cava with orthogonal vectors for volume calculation

Validation

The validation study was performed to confirm the findings using the identified variables from Model 2; it involved parameters estimated from 26 randomly selected observations and we obtained the predictive values of that model with the remaining observations. Using the 10 mmHg CVP cut-point, we achieved an area under the ROC curve of 0.83 (95% CI 0.67–0.99), with specificity of 50% and sensitivity of 93%.

Discussion

This study identified a reliable 90% predictive non-invasive approach to approximate CVP in patients with HF using IVC volume measurement based on standardized, breathing-corrected echocardiography data. Findings were compared against invasive, gold-standard Swan-Ganz RHC, and the statistical correlation model was improved when routinely collected echocardiography parameters (MVED and RVEDD) were taken into account (area under ROC of 0.90). This study also confirmed the poor correlation between traditional 2DE to predict CVP, but 2DE remains part of a broad standard of care in many echocardiography laboratories worldwide [10]. Thus, our findings document an easy-to-use and easy-to-implement approach to enhance CVP prediction that shows good correlation with invasive measurement. We were also able to validate an easy-to-use prediction model for CVP in HF that had excellent specificity and satisfactory sensitivity to predict CVP at a 10-mmHg threshold and can easily be incorporated into daily clinical practice (Figs. 5, 6).

Obtaining CVP is an essential component of HF treatment and CVP has been shown to guide prognosis [3]. Despite the need for a reliable, non-invasive method for estimating CVP, there are several challenges to identifying a feasible, consistent and practical approach, as discussed previously [5]. There are a number of factors that influence CVP, making a simple estimation from a single freeze ultrasound image impossible [5]. Therefore, techniques such as having the patient sniff have been used to acquire additional information for better estimation of CVP [12]. However, these approaches are limited by interobserver variability in assessing IVC collapse and venous compliance [10].

Similar to our results, Huguet et al. reported discrepancy for 2DE measurements of CVP, showing systematic underestimation, mostly for 2DE foreshortening artifacts [9]. Given the clinical implications of such measurements in guiding medical strategy in HF decompensation or cardiogenic shock, the discrepancies between 2DE estimations and actual CVP values are concerning [13]. Thus, a more accurate noninvasive approach for CVP assessment is required [14].

3DE is widely available, simple, can be performed at the bedside and is already part of daily practice, making it a better choice for determining comprehensive IVC geometry [11]. Respiratory position influences IVC geometry [9], which is why our standardized study measurements were reported as breathing-corrected values; in addition, we did not require an additional “sniff” test. Moreover, in contrast to other studies, we investigated an unselected, all-comers HF population, making our findings potentially applicable to a broad group of patients.

Huguet et al. reported significant correlation of IVC area in three-dimensional images with CVP [9]. In contrast, we found no good correlation of IVC area in cross-sectional images with invasively-measured CVP in our HF study population. Our statistical predictive model allows the best CVP approximation reported in literature yet. We used a novel approach to increase correlation, and ours is the first study to include left ventricular function parameters (MVED), along with the appropriate equipment and well-trained sonographers. This makes our approach not only reliable but also easily performable in a routine clinical setting.

With our study findings we encourage clinicians to attempt echocardiography based CVP approximations as a none-invasive alternative to Swan-Ganz catherization. Through implementation of our standardized, breathing corrected, orthogonal vector IVC volume assessment reliable prediction of a CVP > 10 mmHg is possible, which is of explicit clinical interest. When additional adding routinely obtained parameters of RVEDD and MVED we have been able to provide strongest correlation for a CVP above 10 mmHg. Our results suggest that echocardiography based IVC volume assessment may represent a feasible and easily applicable method for volume status evaluation in HF patients, with the potential to avoid risks of invasive catherization.

Larger studies in wider patient groups are needed to better determine the potential implications of our findings in clinical decision making and for guiding medical therapy in HF. 3DE IVC assessment may represent a more feasible and easily applicable method for evaluating volume status and measuring CVP in HF, eliminating the risks associated with RHC and preventing misinterpretation when 2DE estimates of IVC are used. However, 3DE is expensive and not widely available, making our simple method of IVC volume assessment relatively attractive. Additional calculations are necessary to determine the best predictive value of our findings. Ease of use of these techniques could be improved by incorporation of the underlying calculations into echocardiography software.

Limitations

This study included a relatively small sample size, the majority of whom were male, and HF severity was moderate (mean NYHA class 2.23). Therefore, the findings can only be generalized to populations with similar characteristics to those in our study. The image quality of echocardiography measurements (both 2DE and 3DE) is limited in obese patients with HF, those who have had cardiac surgery and in patients with left ventricular assist devices, meaning that use of echocardiography to assess hemodynamics is not applicable in every patient. In addition, other comorbidities, such as chronic lung diseases, can also worsen image quality. Finally, our prediction model needs to be tested with data from other settings and centers and, in particular, its robustness to measurement errors needs further evaluation.

Conclusion

2DE grading of IVC alone provided no reliable predictive value for CVP approximation compared with Swan-Ganz gold-standard of invasively measured CVP, limiting the role for this commonly-used technique in clinical decision making and medical therapy guidance. In contrast, 3DE facilitated identification not only of IVC size but also shape, allowing much better and more accurate CVP estimation. Thus, standardized IVC volume assessment imaging provided good information to allow prediction of CVP > 10 mmHg when the routinely obtained echocardiography parameters RVEDD and MVED were added (area under the curve 0.90) and correlation with invasively measured pressure was strongest when CVP is > 10 mmHg. Our results suggest that IVC volume assessment may represent a more feasible and easily applicable method for volume status evaluation and CVP measurement in HF, allowing the risks of RHC and misinterpretation based on 2DE data to be avoided.

References

Ambrosy AP, Fonarow GC, Butler J, Chioncel O, Greene SJ, Vaduganathan M, Nodari S, Lam CSP, Sato N, Shah AN, Gheorghiade M (2014) The global health and economic burden of hospitalizations for heart failure: lessons learned from hospitalized heart failure registries. J Am Coll Cardiol 63:1123–1133. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2013.11.053

Drazner MH, Rame JE, Stevenson LW, Dries DL (2001) Prognostic importance of elevated jugular venous pressure and a third heart sound in patients with heart failure. N Engl J Med 345:574–581. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa010641

Uthoff H, Thalhammer C, Potocki M, Reichlin T, Noveanu M, Aschwanden M, Staub D, Arenja N, Socrates T, Twerenbold R, Mutschmann-Sanchez S, Heinisch C, Jaeger KA, Mebazaa A, Mueller C (2010) Central venous pressure at emergency room presentation predicts cardiac rehospitalization in patients with decompensated heart failure. Eur J Heart Fail 12:469–476. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurjhf/hfq024

Adams KF Jr, Fonarow GC, Emerman CL, LeJemtel TH, Costanzo MR, Abraham WT, Berkowitz RL, Galvao M, Horton DP, ASA Committee, Investigators (2005) Characteristics and outcomes of patients hospitalized for heart failure in the United States: rationale, design, and preliminary observations from the first 100,000 cases in the Acute Decompensated Heart Failure National Registry (ADHERE). Am Heart J 149:209–216. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ahj.2004.08.005

McGee SR (1998) Physical examination of venous pressure: a critical review. Am Heart J 136:10–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0002-8703(98)70175-9

Fox H, Hemmann K, Lehmann R (2020) Comparison of transthoracic and transesophageal echocardiography for transcatheter aortic valve replacement sizing in high-risk patients. J Echocardiogr 18:47–56. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12574-019-00448-7

Mullens W, Abrahams Z, Francis GS, Sokos G, Taylor DO, Starling RC, Young JB, Tang WHW (2009) Importance of venous congestion for worsening of renal function in advanced decompensated heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol 53:589–596. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2008.05.068

Merrer J, De Jonghe B, Golliot F, Lefrant JY, Raffy B, Barre E, Rigaud JP, Casciani D, Misset B, Bosquet C, Outin H, Brun-Buisson C, Nitenberg G, C French Catheter Study Group in Intensive (2001) Complications of femoral and subclavian venous catheterization in critically ill patients: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 286:700–707. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.286.6.700

Huguet R, Fard D, d'Humieres T, Brault-Meslin O, Faivre L, Nahory L, Dubois-Rande JL, Ternacle J, Oliver L, Lim P (2018) Three-dimensional inferior vena cava for assessing central venous pressure in patients with cardiogenic shock. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 31:1034–1043. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.echo.2018.04.003

Brennan JM, Blair JE, Goonewardena S, Ronan A, Shah D, Vasaiwala S, Kirkpatrick JN, Spencer KT (2007) Reappraisal of the use of inferior vena cava for estimating right atrial pressure. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 20:857–861. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.echo.2007.01.005

Seo Y, Iida N, Yamamoto M, Machino-Ohtsuka T, Ishizu T, Aonuma K (2017) Estimation of central venous pressure using the ratio of short to long diameter from cross-sectional images of the inferior vena cava. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 30:461–467. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.echo.2016.12.002

Rudski LG, Lai WW, Afilalo J, Hua L, Handschumacher MD, Chandrasekaran K, Solomon SD, Louie EK, Schiller NB (2010) Guidelines for the echocardiographic assessment of the right heart in adults: a report from the American Society of Echocardiography endorsed by the European Association of Echocardiography, a registered branch of the European Society of Cardiology, and the Canadian Society of Echocardiography. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 23:685–713. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.echo.2010.05.010 (quiz 786–688)

Chakko S, Woska D, Martinez H, de Marchena E, Futterman L, Kessler KM, Myerberg RJ (1991) Clinical, radiographic, and hemodynamic correlations in chronic congestive heart failure: conflicting results may lead to inappropriate care. Am J Med 90:353–359. https://doi.org/10.1016/0002-9343(91)80016-f

De Vecchis R, Baldi C, Giandomenico G, Di Maio M, Giasi A, Cioppa C (2016) Estimating right atrial pressure using ultrasounds: an old issue revisited with new methods. J Clin Med Res 8:569–574. https://doi.org/10.14740/jocmr2617w

Acknowledgements

Open Access funding provided by Projekt DEAL.

Funding

No outside finding was obtained for this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

All authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee (Ethics Committee of Ruhr University Bochum, Reg-No. 2017-197) and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Szymczyk, T., Sauzet, O., Paluszkiewicz, L.J. et al. Non-invasive assessment of central venous pressure in heart failure: a systematic prospective comparison of echocardiography and Swan-Ganz catheter. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging 36, 1821–1829 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10554-020-01889-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10554-020-01889-3