Abstract

This study examines the factors that are likely to influence emergency managers’ willingness and ability to report to work after a catastrophic event using the Cascadia Subduction Zone earthquake threat as an example. The population approached for participation in this study was state-level emergency managers in Oregon and Washington, the areas anticipated to be the most impacted by the Cascadia Subduction Zone earthquake. Concept mapping was utilized to elucidate factors influencing emergency managers’ ability and willingness to report to work following a catastrophic earthquake, as well as to identify specific strategies for addressing these factors to facilitate reporting to work. The six-step concept mapping process (i.e., preparation, generation, structuring, representation, interpretation, and utilization) is a structured and integrated mixed-method process that employs both qualitative and quantitative components to gather ideas and concepts of participants, and subsequently produces visual representation of these ideas and concepts through multivariate statistical methods (Caracelli and Green in Eval Program Plan 12(1):45–52, 1993; Kane and Trochim in Concept mapping for planning and evaluation, Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks, 2007). Results influence across a wide range of the levels of the ecological framework for both ability (transit barriers and infrastructure impacts, family/pet health and safety, social support and preparedness, work-related influences, personal health and resources, professional obligations, and location) and willingness (family/community preparedness and safety, emergency management responsibility and professionalism, motivation to come to work, transit barriers and infrastructure impacts, professional contribution, physical and mental health, worksite operations: structure and process, family first, personal contribution and history).

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

An oral history persisted for generations among indigenous peoples in the Pacific Northwest detailing catastrophic earthquakes and resulting tsunamis (Ludwin et al. 2005); however, for nearly 300 years after initial contact between indigenous peoples and European explorers, modern infrastructure was constructed and populations boomed in this region under the assumption of low earthquake risks (Henry and Beals 1991). In the early 1980s an important paradigm shift occurred due to pioneering research documenting evidence of past catastrophic earthquakes and tsunamis affecting the Pacific Northwest, and establishing likelihood for future earthquakes (Atwater 1987). The area of concern is known as the Cascadia Subduction Zone where, through a geological process of subduction, a tectonic plate descends below another tectonic plate resulting in seismic activity (Frankel and Petersen 2008). Based on recurrence periods of previous earthquakes along the subduction zone, researchers estimate that the likelihood of a magnitude 9.0 or greater earthquake along the Cascadia Subduction zone to be a one-in-ten chance within the next 50 years (Goldfinger et al. 2012).

Although the Cascadia Subduction Zone earthquake is a significant threat to the Pacific Northwest, the emergency management community is documented to face complex challenges for this catastrophic event (FEMA 2016). One of the most significant concerns is that “staff available to an organization will likely be limited” (FEMA 2013, pp. A-1). This concern is supported by previous research and historical examples of disaster that have found that staff may not always be able and willing to report to work. The availability of emergency managers is of particular importance given their role in orchestrating the necessary responses across a broad range of emergency responders. Emergency managers “protect communities by coordinating and integrating all activities necessary to build, sustain, and improve the capability to mitigate against, prepare for, respond to, and recover from threatened or actual natural disasters, acts of terrorism, or other man-made disasters” (FEMA 2007). However, there is a paucity of research related to ability and willingness to report to work for catastrophic earthquakes, and particularly for emergency managers.

2 Background

Previous research on health care providers and first responders can help to frame our understanding of ability and willingness of emergency managers to report to work after a catastrophic earthquake. These studies suggest that there are several factors that may influence willingness and ability to report to work including the type of disaster, as well as a range of including individual, social, organizational, and community/built environment factors.

When examining ability and willingness to report to work, the type of disaster (ex. earthquake, influenza pandemic, flood). The majority of published research attempts to quantify the level of ability and willingness to report to work for specific hypothetical disasters. These studies, all among healthcare workers, found that 53–95% would be willing to report to work following an earthquake (Burke et al. 2010; Charney et al. 2014; Mercer et al. 2014; Natan et al. 2014; Cone and Cummings 2006; Stergachis et al. 2011). A single study addressed the ability to report to work after an earthquake (Stergachis et al. 2011), and found that fewer respondents would be able to report to work than would be willing to report to work after an earthquake (74% vs. 88%). Of interest, among studies examining various scenarios for willingness to report to work, including an earthquake scenario, one study discovered that fewer respondents reported being willing to report to work for an earthquake than for influenza pandemic (88% vs. 89%) (Stergachis et al. 2011). Furthermore, this same study also found that even fewer respondents reported they would be able to report to work for an earthquake than for influenza pandemic (74% vs. 95%) (Stergachis et al. 2011). This is a noteworthy finding, as this study is the only one to utilize a population specifically from the Pacific Northwest. Previous research has reinforced that factors influencing reporting to work are complex; however, to date no research has examined the factors influencing emergency manager ability and willingness to report to work.

Previous research has also identified a number of other factors influencing ability and willingness to report to work in a disaster. These include individual (e.g., occupation, sense of responsibility, fear/concern for family and/or self, and personal health issues) interpersonal (e.g., child, elder and pet care obligations), and organizational influences (e.g., liability, availability of employer-provided personal protective equipment, and safety measures) (Adams and Berry 2012; Balicer et al. 2006; Davidson et al. 2009; DiMaggio et al. 2005; Gershon et al. 2010; Mackler et al. 2007; Ogedegbe et al. 2012; Qureshi et al. 2005; Shapira et al. 1991).

This previous work helps to lay the foundation for examining the factors that influence ability and willingness of emergency managers to report to work after a catastrophic earthquake. There are still, however, several gaps in knowledge. For example, few of the previous studies have examined ability and willingness to report to work following an earthquake. This is important because previous research has shown that types of influences and even degree of willingness and ability to report to work differ by type of disaster (Stergachis et al. 2011). Furthermore, no studies have specifically examined the factors influencing ability and willingness to report to work following an earthquake for emergency managers. Given the leading role of emergency managers during times of disaster and the existing knowledge gap, this is an important area warranting study. This study utilizes a mixed-method approach, concept mapping, to identify factors influencing ability and willingness of emergency managers to report to work and strategies for addressing the most important factors identified.

3 Methods

Concept mapping was utilized to elucidate factors influencing emergency managers’ ability and willingness to report to work following a catastrophic earthquake (e.g., Cascadia Subduction Zone earthquake), as well as to identify specific strategies for addressing these factors to facilitate reporting to work. The multi-step concept mapping process is a structured and integrated mixed-method process that employs both qualitative and quantitative components to gather ideas and concepts of participants, and subsequently produces visual representation of these ideas and concepts through multivariate statistical methods (Caracelli and Green 1993; Kane and Trochim 2007). For the purpose of this study, these steps were broken out into three separate phases (i.e., Phase 1: Brainstorming, Phase 2: Sorting and Rating, and Phase 3: Interpretation and Utilization). Although this methodology is well-documented in the published literature with the purpose of identifying influential factors for a particular behavior of interest (Dulin-Keita et al. 2015; Iwelunmor et al. 2015; O’Campo et al. 2005; Walker et al. 2011), this is the first study to utilize concept mapping to identify influential factors for reporting to work for emergency managers.

The population approached for participation in this study was state-level emergency managers in Oregon and Washington, the areas anticipated to be the most impacted by the Cascadia Subduction Zone earthquake. Prior to recruitment, letters of support were obtained from senior management for the two state emergency management departments. For the purposes of this study, participants were initially invited to take part in brainstorming factors related to ability and willingness to report to work for a 9.0 Cascadia Subduction Zone earthquake (i.e., Phase 1). Participants who completed the generation step had the opportunity to opt into sorting and rating these statements (i.e., Phase 2). Lastly, participants who completed the structuring step had the opportunity to opt into the group process as is described more specifically below (i.e., Phase 3).

Prior to recruitment and data collection, study phases were approved by the Saint Louis University Institutional Review Board (IRB).

3.1 Phase 1: brainstorming

Within Phase 1, participants brainstormed factors influencing reporting to work after a 9.0 Cascadia Subduction Zone event using an online concept mapping tool. Focus prompts for this study were “What would influence your ability to report to work after a 9.0 Cascadia Subduction Zone earthquake?” and “What would influence your willingness to report to work after a 9.0 Cascadia Subduction Zone earthquake?” In addition, a brief set of questions was also included in order to identify the individual and organizational characteristics of the sample (e.g., number of years working as an emergency manager, gender, marital status, etc.). The online process was pilot tested with emergency managers and subject matter experts from outside the study area to determine the relevance of questions and overall quality of the online tool. While slight modifications were made to the instructions, overall, the pilot test revealed instructions and questions were relevant and clear, and the length was appropriate.

The Phase 1 tool was hosted online through Qualtrics®, with the link emailed to participants by a manager in their emergency management organization. A link to the tool was sent to 165 individuals with 33 total responses for a 20% response rate. A total of 130 statements were generated related to ability to report to work (median = 4, range 1–8), and 171 statements related to willingness to report to work (median = 5, range 1–15). All statements were then examined and duplicative statements were synthesized separately for ability and willingness to create a final list of unique statements suitable for sorting and rating by participants in step 3 (i.e., structuring). The final lists contained 71 statements related to ability to report to work and 94 statements related to willingness to report to work. Upon completion, participants were given the opportunity to opt-in online in order to participate in the structuring step.

3.2 Phase 2: sorting and rating

The unique statements produced in Phase 1′s brainstorming exercise were placed in the online concept mapping system Concept Systems® Global Max™ allowing participants to sort all of the unique statements into like groups according to their conceptual similarities and rate the importance of each statement. In total, 24 individuals opted-in for Phase 2 at the end of Phase 1. For ability, completion rates (finished/started) were 85% (17/20) for sorting and 100% (17/17). For willingness, completion rates were 95% (19/20) for both sorting and rating. In a meta-analysis of published concept mapping studies, the average web-based completion rate was 52% for sorting, and 68.7% for rating (Rosas and Kane 2012).

After the participants sorted the statements into their respective groups, they labeled each group according to what the group represents to them. For example, one participant labeled a group “monetary” if the group contained statements pertaining to increased pay, overtime pay, employer contributions to child care, etc. After the sorting, participants then rated each unique statement. Each of the statements was rated by participants using an ordinal 5-point Likert scale, ranging from “relatively unimportant” to “extremely important” in relation to ability to report to work, and separately in relation to willingness to report to work. Questions to determine individual and organizational characteristics were included to allow for comparison between participants in the sorting phase and those in the previous brainstorming and subsequent interpretation and utilization steps. Afterward, participants were given the opportunity to opt-in online in order to participate in the final data collection phase (i.e., steps 5 interpretation and 6 utilization).

3.2.1 Concept mapping analyses

Data from Phase 2 was analyzed using Concept Systems® Global MaxTM to produce visual concept maps of the data that demonstrate relationships between statements. This involves a sequential process of similarity matrix creation, multidimensional scaling, hierarchical cluster analysis, and ultimately cluster solution map formation. The similarity matrix was formed through aggregation of sorting data and shows the total number of times a statement was grouped with another statement by participants. Next, the similarity matrix was used to create point maps through multidimensional scaling analysis. As a result of the analysis, each unique statement was given X and Y coordinate values that were plotted as a point onto a two-dimensional concept map. Using the X–Y coordinates generated from the multidimensional scaling analysis, hierarchical cluster analysis was employed to produce defined geometric clusters on a map (i.e., cluster solution map) that illustrate major aggregated concepts.

For analyses comparing average importance ratings of clusters between sub-groups of participants, the median importance value of each unique statement was determined as the most appropriate measure of central tendency for ordinal data, then the average of these median statement scores within each cluster was calculated. As a measure of correlation in pattern matching, the Spearman’s ρ was calculated for the overall strength of agreement in importance rating between the sub-groups. Due to potential limitations in sample size, 95% confidence intervals were calculated utilizing bootstrapping (SPSS® 24.0) to determine upper and lower bounds and to determine if differences in importance ratings were meaningful. The individual clusters were examined to determine any significant differences in agreement in importance ratings between sub-groups. The Mann–Whitney U test was calculated to determine the if subgroup differences in cluster importance ratings were statistically significant. The Mann–Whitney U test, a nonparametric version of the t test, is appropriate for the small sample size and does not assume a specific distribution (McKnight and Najab 2010). For the statistically significant Mann–Whitney U tests, effect sizes were calculated to determine the magnitude of difference using the formula r = Z/√n (Fritz et al. 2012).

3.3 Phase 3: interpretation and utilization

In the third phase, participants provided input on face validity of the clusters created through the concept mapping analysis and ultimately developed strategies to facilitate reporting to work after a catastrophic earthquake. Sessions were held onsite in each of the two study locations (i.e., Oregon, and Washington). The clusters created by the concept mapping process were presented to each of these groups to obtain input on the face validity of the clusters developed including the statements included in each and titles (member checking) (Kane and Trochim 2007). The participants (n = 8 in Oregon, n = 3 in Washington) then identified criteria for prioritizing which clusters should be addressed first. The criteria for prioritization included the importance of the issue to emergency managers, importance to the organization and community, organization and community support for working on this issue, financial feasibility of working on this issue, amount of needed time to change the issue, public perception, legal ramifications, and organized labor considerations. Once these criteria were established, participants prioritized the clusters. A form of nominal group process was used to facilitate this process. Once the top clusters were identified, the groups held discussions to develop strategies that would alter a factor in a way that it would increase ability and willingness to report to work after a catastrophic earthquake.

4 Results

4.1 Individual and organizational characteristics

Through three phases of the study, information regarding individual and organizational characteristics were collected to describe the sample (Table 1). In all there were four points of data collection in three phases: The data from the four collection points are described below.

4.1.1 Age, race, gender, and education

The average age of participants was in the upper 40 s and similar across Phase 1 (48.1 years), Phase 2 Ability (48.5 years) and Phase 2 Willingness (47.2 years), and Phase 3 (49.4 years). The large majority of participants were white (Phase 1: n = 32, 97.0%; Phase 2 Ability: n = 16, 94.1%; Phase 2 Willingness: n = 18, 94.7%; Phase 3: n = 11, 100%) with the other only racial representation being ‘Other’ (Phase 1: n = 1, 3.0%; Phase 2 Ability: n = 1, 5.9%; Phase 2 Willingness: n = 1, 5.3%; Phase 3: n = 0, 0%). Across all phases, participants were slightly more likely to be male (Phase 1: n = 22, 66.7%; Phase 2 Ability: n = 9, 52%; Phase 2 Willingness: n = 11, 57.9%; Phase 3: n = 7, 63.6%) than female (Phase 1: n = 11, 33.3%; Phase 2 Ability: n = 8, 46.1%; Phase 2 Willingness: n = 8, 42.1%; Phase 3: n = 4, 36.4%). Participants were also highly educated, with more than a third having attained a master’s, professional, or doctorate degree (Phase 1: n = 13, 39.4%; Phase 2 Ability: n = 6, 35.3%; Phase 2 Willingness: n = 7, 36.9%; Phase 3: n = 5, 45.5%).

4.1.2 Caregiving responsibilities

In regard to caregiving responsibilities, more than a third of participants identified as having children in the household or being responsible for the care of an elder (Phase 1: n = 17, 51.5%; Phase 2 Ability: n = 6, 35.3%; Phase 2 Willingness: n = 7, 36.8%; Phase 3: n = 5, 45.5%). A large majority of participants were also pet owners, with more than two-thirds indicating they were responsible for the care of a pet (Phase 1: n = 23, 69.7%; Phase 2 Ability: n = 14, 82.4%; Phase 2 Willingness: n = 14, 73.7%; Phase 3: n = 9, 81.8%).

4.1.3 Employer, and distance to work

Participants in each phase were more likely to be emergency managers with the State of Oregon (Phase 1: n = 18, 54.5%; Phase 2 Ability: n = 12, 70.6%; Phase 2 Willingness: n = 13, 68.4%; Phase 3: n = 8, 72.5%) than the State of Washington. On average, participants in each phase lived more than 15 miles away from work (Phase 1: 18.8 miles; Phase 2 Ability: 16.4 miles; Phase 2 Willingness: 19.3 miles; Phase 3: 21.2 miles).

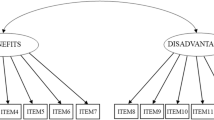

4.2 Cluster solutions maps

Separate cluster solution maps were produced for ability to report to work and willingness to report to work. Each map represents unique concepts visually and demonstrate relationships between the individual 71 statements for ability to report to work, as well as the 94 individual statements related to willingness to report to work (Figs. 1, 2).

4.2.1 Ability to report to work cluster solution map

To determine the final cluster solution map for ability to report to work, cluster solution maps were analyzed beginning with a 20-cluster solution map and working downward as clusters merged. By examining the statements in each cluster to ensure clusters that were merged contained conceptually similar concepts it was determined that the 7-cluster solution map best represented the underlying concepts (Fig. 1). In addition, the stress value of the final cluster solution map was 0.20, indicating the map is an appropriate representation of the underlying data. This value, ranging from 0 to 1, measures “the degree to which the distances on the map are discrepant from the values in the input similarity matrix”, with a low stress value indicating a better overall fit of the map to the data (Kane and Trochim 2007).

4.2.2 Willingness to report to work cluster solution map

As with ability to report to work, cluster solution maps for willingness were analyzed beginning with a 20-cluster solution map and working downward as clusters merged. By examining the statements in each cluster to ensure clusters that were merged contained conceptually similar concepts it was determined that the 9-cluster solution map best represented the underlying concepts (Fig. 2). For the final cluster solution map for willingness to report to work, the stress value was 0.25 indicating the map is an appropriate representation of the underlying data.

4.3 Importance rating

Cluster mean importance ratings were calculated for each of the clusters in the final solutions map for ability and the final solutions map for willingness (Tables 2, 3). The cluster mean scores reflect the rating scale from 1—relatively unimportant to 5—extremely important in relation to one’s willingness to report to work,

and again separately in relation to one’s ability to report to work. The final cluster solutions maps for ability and willingness are presented below with cluster mean importance ratings for each cluster.

4.3.1 Ability to report to work: cluster mean importance ratings

Overall, the cluster with the highest cluster mean importance rating for ability to report to work was the Transit Barriers and Infrastructure Impacts cluster (Table 2). This is followed in importance rating by Family/Pet Health and Safety, Social Support and Preparedness, Work-related Influences, Personal Health and Resource, Professional Obligations, and finally Location, respectively.

4.3.2 Willingness to report to work: cluster mean importance ratings

Overall, in relation to willingness to report to work, Family/Community Preparedness and Safety was the cluster with the higher mean importance rating (Table 3). The next highest mean importance ratings, respectively, were Emergency Management Responsibility and Professionalism, Motivation to Come to Work, Transit Barriers and Infrastructure Impacts, Professional Contribution, Physical and Mental Health, Worksite Operations: Structure and Process, Family First, and lastly Personal Contribution and History.

4.4 Subgroup results

Results from subgroup analyses showed statistically significant differences in the importance ratings of specific factors (e.g., clusters). These differences in agreement were discovered for both factors influencing ability to report to work as well as factors influencing willingness to report to work. The subgroups with statistically significant differences in importance ratings are discussed below.

4.4.1 Ability to report to work: gender, distance to work

Results from this study found that Work-related Influences (ex. communications, status of workplace building, remote work ability, employer provision of basic needs) and Personal Health and Resources (ex. personal health status, access to medication, consisted of home, availability of personal resources) differed significantly between male and female participants in regard to the factor’s importance in their ability to report to work after a catastrophic earthquake. Although the factor Work-related Influences was only the fourth most important factor in general for ability to report to work, and the very least important factor for males, it was the second most important for females. The factor Personal Health and Resources was also rated more important by female participants than by males in relation to their ability to report to work. It was only the fifth most important factor overall, and the third least important for males; however, Personal Health and Resources was the third most important factor for females. When strategies are developed to increase ability to report to work, it is important to not overlook the importance placed on these factors by female emergency managers.

The factor Work-related Influences was also found to differ in importance rating by distance to work, specifically between those who lived less than ten miles away from work and those who lived ten miles or more away from work, with those living closer to work finding this factor to be more important in regard to their ability to report to work. This factor was the second most important factor for those who lived less than ten miles away from work, but the second-to-lowest factor for those who lived ten miles or more away from work. This is an intriguing finding, and it is postulated that participants living less than ten miles away viewed the Work-related Influences factor as more important as it serves as a proxy for the severity of their own situation after a catastrophic earthquake due to their relatively close proximity to work. For example, if the workplace building was not standing then it may be likely their own home was not standing.

4.4.2 Willingness to report to work subgroups: gender, employer, distance to work

Pertaining to gender, this study found that Worksite Operations: Structure and Process differed between male and female participants in regard to the factor’s importance in their willingness to report to work after a catastrophic earthquake. Overall, this factor was ranked as more important by female than male participants. The difference in importance of Worksite Operations: Structure and Process for female emergency managers is a meaningful finding for continuity of operations planning. To ensure all emergency managers are willing to report to work (i.e., both male and female), organizations should not only ensure the worksite is able to withstand the earthquake but also ensure that all aspects of an employee’s role in worksite operations are clarified (e.g., employer policies for reporting to work, expectations for hours required to work, critical nature of employee function in response).

The importance of two factors, Emergency Management Responsibility and Professionalism and Professional Contribution, differed significantly between those in Oregon and those and Washington. While both Oregon and Washington participants indicated Emergency Management Responsibility and Professionalism was one of the top two most important factors in relation to its importance in their willingness to report to work, it was the top factor among all factors for those in Washington. Agreement also differed significantly between Oregon and Washington in regard to the importance of Professional Contribution in their willingness to report to work. While this was the third most important factor among all other factors emergency managers in Washington, it was the second least important factor for those in Oregon. This is an intriguing, although more information regarding the complexities of the employer (ex. Organizational culture) were not captured as part of this study and may warrant further study.

Regarding distance to work, the factor Family/Community Preparedness and Safety was also found to differ significantly in importance between those who lived less than ten miles away from work and those who lived ten miles or more away from work, with those living closer to work finding this factor to be more important in regard to their willingness to get to work. However, even though a significant difference in importance was observed it should be noted that the factor was still among the top three factors for those who lived less than ten miles away from work as well as for those who lived ten miles away from work or more.

4.5 Interpretation and utilization

Through the interpretation and utilization processes in Phase 3, participants indicated that the data made sense to them, was perceived as complete and accurate, and was encompassing of their views on influential factors for both ability to report to work and willingness to report to work after a catastrophic earthquake (e.g., Cascadia Subduction Zone earthquake). Afterward, when developing criteria to consider when selecting factors to prioritize, the final list included: importance of the issue to emergency managers, the organization, cost, time, public perception, legal ramifications, potential organized labor considerations, existing public policy, subject matter expert recommendations, and overall perceived feasibility of addressing the factor. For ability to report to work, participants from Oregon selected Personal health and resources, Transportation barriers and infrastructure impacts, and Location. Participants in Washington selected Work-related influences, Family/pet health and safety, and Social support and preparedness as the factors on which to focus for strategy development for increasing ability to report to work after a catastrophic earthquake. For willingness to report to work, participants from Oregon selected Physical and Mental Health, Family and Community Preparedness and Support, and Family First. Participants from Washington selected Worksite Operations: Structure and Process, in addition to Family First, and Emergency Management Responsibility and Professionalism to focus on strategy development for in regard to increasing willingness to report to work after a catastrophic earthquake.

4.6 Strategy development: ability to report to work

Participants developed numerous and diverse strategies regarding ability to report to work in an effort to facilitate emergency manager’s ability to report to work after a catastrophic earthquake.

As it relates to the factor Personal Health and Resources, the improvement of employee health prior to event was suggested as a way to ensure employees were able to report to work, such as the employee responsibility to achieve/maintain health and the employer to provide physical fitness resources. Multiple strategies addressed retrofitting of essential staff member homes so that they are resilient to the shaking during an earthquake as a strategy to increase employee ability to report to work. These strategies included employer-provided funding for earthquake retrofitting, an employee-led program for earthquake retrofitting homes, and tax write offs for retrofitting expenses. Specifically, regarding personal resources, participants suggested that employees achieve sufficient levels of essential resources such as food, water, medication, first aid equipment. For the employer, it was suggested that the employer not only encourage employees to obtain sufficient personal resources but also provide related training and education.

Participants suggested a number of strategies to increase employee ability to report to work related to Transit Barriers and Infrastructure Impacts. Employer provision of transportation to and from work was a main strategy, which included planned pick-up locations for employees who live far away. Participants suggested that employees should ensure their personal vehicles are available by keeping up with regular vehicle maintenance, and keeping their vehicle fully fueled. Participants also suggested that employees be encouraged to purchase four-wheel drive vehicles given possible physical barriers in getting to work. It was also suggested that employees ensure their garages are seismically retrofitted to withstand earthquake shaking. Participants indicated that employers should address fuel needs of employees for travel, as employees may not have enough fuel to return to work for the next operational period if public fuel stations are inoperable. The creation of public transportation system resilience was an important focus, which would involve increased government investment in earthquake resistant and reliable transportation infrastructure, more thorough engineering evaluation of existing transportation systems. Participants suggested working with departments of transportation and the legislature to prioritize investment in resilient transportation infrastructure. Government establishment of alternate transportation systems and employee utilization of these routes was also suggested as a strategy to increase the ability to report to work. This includes government investment in designated bike and walking lanes, and employees becoming learning the biking and walking routes to work. Strategies were suggested to mitigate the physical barriers that would result from an earthquake, such as burying lines and trimming and/or cutting trees along major transit paths. Some barriers are not due to physical debris, but rather authority. Participants suggest employer-developed policies and procedures to ensure employees are permitted to travel to and from work, which could include credentialing to be allowed past law enforcement and through restricted areas. In reference to the distance as a barrier to the ability to report to work, strategies included employer policies restricting the distance employees can live from work to ensure employees are able to report to work.

Strategies for Work-related Influences as an influential factor for ability to report to work centered around resilient work facility, remote work, robust continuity of operations planning, and the provision of basic employee needs. Participants suggested that the physical workplace building should be constructed to seismic standards, and if not already it should be retrofitted to withstand seismic shaking. If the employee is unable to report to work at the main work facility, remote work at nearby emergency management emergency operation centers should be allowed to assist in the overall response effort. Participants noted that remote work policies need to be updated, mutual aid agreements for staff at eligible organizations need to be established, and cross-training of employees needs to occur to ensure the success of remote work as a solution for ability to report to work. Continuity of operations planning was seen as an important solution. Participants emphasized continuity of operations plans should be written, regularly updated, communicated to all staff, trained on, and exercised to include family members. Additionally, employers should create a workplace that can support employee everyday basic needs, which include access to food and water, and capability for sleeping, resting, and exercising while at work. Employers should also create a workplace that can provide for employee emergency needs such as making available medical supplies, medication reserves, and pre-planning to have medical support at workplace.

Strategies that would address Location as a factor influencing ability to report to work were found to be similar/complementary to those for other factors. In terms of Location as well as Transit Barriers and Infrastructure Impacts, participants suggested employer-created policies restricting the distance employees can live from work to ensure employees are able to report to work. However, participants also emphasized that employees should take it upon themselves to opt for housing solutions that are close to work. Remote work capabilities, as mentioned in Work-related Influences, are applicable for addressing Location as a factor influencing ability to report to work.

Solutions for Family/Pet Health and Safety included the creation of employer policies, plans, and facilities for bringing family members and pets to work with the employee. For the employee, a solution included creating a family plan that includes designating alternate facilities for childcare, eldercare, and petcare that are likely operational after an earthquake. These facilities should be close to the workplace.

To address Social Support and Preparedness, social networking with community members, other employees, and between organizations was proposed as a solution for fostering social support networks that increase ability to report to work. Participants also provided solutions that include training and education to facilitate the development of preparedness skills for employees, their families, and the community members.

4.7 Strategy development: willingness to report to work

Participants identified considerable number of strategies to address factors in a way that would increase willingness to report to work after a catastrophic earthquake.

For Physical and Mental Health, participants suggested employee medication and/or resources for obtaining medication as needed to support employee medical needs would need to be provided at work. Furthermore, provision of medical support and first aid was identified as an important strategy for addressing Physical and Mental Health as it relates to improving willingness to report to work after a catastrophic earthquake. Part of this strategy could involve employer-provided training for first aid to and first aid resources for employees and their families. The availability of counselors, massage therapists, and therapy dogs at work were all identified as strategies to address the Physical and Mental Health factor in terms of willingness to report to work, specifically as it relates to ensuring employees have access to resources to facilitate healthy coping responses. As this study addresses factors after a catastrophic earthquake with mass fatalities, psychological counseling and therapy resources specific to loss-of-life issues was also seen as important for addressing Physical and Mental Health as it relates to emergency manager willingness to report to work. The planned provision of sanitation services by employer for after a catastrophic earthquake, and the absolute assurance by the employer these services would be provided, was identified as a strategy for increasing willingness to report to work.

Participants provided a variety of suggested strategies to increase employee willingness to report to work related to Family and Community Preparedness and Support. The provision of care for family and pets was a priority, which included onsite daycare, emergency dorms/housing, and basic needs and supplies to take care of family and pets. Family and community preparedness strategies to increase willingness to report to work included trainings on how to be prepared and emergency communications training (e.g., amateur radio). Participants indicated that employers should allow employees to participate in community preparedness activities on work time, as this fosters community preparedness as well as employee preparedness to support the mission of the agency. Emergency management agencies should promote self-sustainment and community resilience through elimination of food deserts and locally sourced food supplies. Strategies also focused on communication. Ensuring communication capability between employees and their families was seen as important, with strategies including the creation of robust primary and alternative communication infrastructure so communication can take place as well as plans, policies, and training for family communication after a catastrophic earthquake. This encompasses initial safety checks, but also continued assurance provided by communication capability between employees and loved ones.

As it relates to the factor Worksite Operations: Structure and Process, the resilience of workplace structure was a main focus. Governments should focus on the funding of emergency management organizations to ensure buildings can withstand a catastrophic earthquake, and also ensure the site can maintain power and communications–existing structures can potentially be retrofitted for earthquake resilience. Strategies for worksite processes included training to ensure that the workplace is organized enough to operate after an earthquake. Willingness to report to alternate work locations is an alternative strategy when reporting to the main worksite is not an option. Continuity of operations plans will need to be robust and employees must be trained on the plan to increase certainty around employer expectations of employees for reporting to work. Clear workplace policies and procedures are suggested as a strategy to complement continuity planning.

Strategies for Family First centered around ensuring family members (to include pets as part of the family) can be taken to work, which complements the strategies for employer provision of care strategies in Family and Community Preparedness and Support. The establishment of a family plan was also suggested as part of terms of employment in an emergency management organization, with the additional strategy for the employer to promote training and exercise of family preparedness plans. Creation of policies limiting employee time away from family is another strategy for increasing willingness to report for work while recognizing the factor Family First.

For Emergency Management Responsibility and Professionalism, strategies were innovative in that they suggested fostering a culture of excellence within emergency management organizations. Part of this strategy could entail development and commitment to a professional oath that emphasizes the mission and sense of duty of the organization. Another strategy involves creating a financial incentive for those considered present for duty, recognizing difficulty of reporting to work after a catastrophic earthquake and rewarding those who strive to overcome barriers.

5 Discussion

The purpose of this study was threefold: to identify factors influencing the ability of emergency managers to report to work following a catastrophic earthquake, to identify factors influencing the willingness of emergency managers to report to work following a catastrophic earthquake, and to develop strategies to address factors elucidated through the study process. Previous research on reporting to work has centered largely on healthcare workers, with no previous research focused on emergency managers. The results of this study identify a complex system of factors that influences emergency managers’ ability and willingness to report to work after a catastrophic earthquake. Furthermore, numerous tangible strategies to increase emergency manager ability and willingness to report to work were identified. The strategies (i.e., plans, programs, trainings, policies, and/or environmental changes) have the potential to guide positive changes at the individual, social, organizational, and/or environmental levels (Sallis et al. 2008).

5.1 Influential factors

5.1.1 Ability to report to work

This study identified seven main factors influencing the ability of emergency managers to report to work after a catastrophic earthquake (i.e., Transit Barriers and Infrastructure Impacts; Location; Professional Obligations; Work-related Influences; Personal Health and Resources; Family/Pet Health and Safety; Social Support and Preparedness). Although these are the first factors to be identified in research for emergency managers, previous research among healthcare workers support the findings of this study with the identification of influential factors such as transportation, safety of family/pets, personal health, healthcare needs, perceived personal effectiveness, and importance of role in a disaster (Adams and Berry 2012; Qureshi et al. 2005; Kruus et al. 2007). However, this study presents novel findings in that influential factors identified for ability to report to work are more complex than previously established in relevant literature. For example, although previous research has identified Family/Pet Health and Safety as a factor in general (Adams and Berry 2012) the sub-aspects of this factor (ex. injury to pets, grief from loss of family member, ability to bring family to work) are able to provide greater understanding of the factor and its influence.

5.1.2 Willingness to report to work

There were nine factors found influencing willingness to report to work for emergency managers following a catastrophic earthquake (i.e., Family/Community Preparedness and Safety; Family First; Physical and Mental Health; Transit Barriers and Infrastructure Impacts; Personal Contribution and History; Motivation to Come to Work; Emergency Management Responsibility and Professionalism; Professional Contribution; Worksite Operations: Structure and Process). Previous research, among healthcare workers, has identified factors that support this study’s findings, although this study’s findings are novel in their identification of new factors and that the factors pertain to emergency managers. This study identified novel influential factors such as Emergency Management Responsibility and Professionalism, which was ranked among the highest of importance among for all identified factors (described in greater detail below). Furthermore, the study results are important in that they have identified factors in greater depth than described in existing literature, with influential factors such as Transportation Barriers and Infrastructure Impacts encompassing a myriad of sub-aspects that frame our understanding of this factor and its influence on willingness to report to work for emergency managers.

5.2 Strategies

Participants developed numerous tangible strategies regarding ability to report to work and willingness to report to work. These strategies addressed prioritized factors and were developed in an overall effort to ensure emergency managers are able and willing to report to work after a catastrophic earthquake.

5.2.1 Strategies for factors influencing ability to report to work

The strategies to address influential factors for ability to report to work were largely centered on the employer and employee. This might have been due to the perception among participants that strategies to be implemented by an employee and their employer (as opposed to changes in the built environment) were most feasible, and therefore more likely to be successful.

Multiple strategies addressed the creation or improvement of plans and policies by the employer. Employer plans and policies could address multiple factors influencing the ability of emergency managers to report to work after a catastrophic earthquake, such as Family/pet health and safety (ex. policies allowing employees to bring family and pets to work), Work-related influences (ex. continuity of operations plans), and Transit Barriers and Infrastructure Impacts (ex. policies limiting distance employees can live from the workplace). Strategies also involved the employer provision of services and resources to employees. This often included their families and pets as well. For example, the employer provision of facilities to house employees, their families, and pets was suggested. Furthermore, strategies also went on to suggest the employer ensure basic needs (ex. food, water, sanitation) were provided as well as emergency needs (ex. psychological support, medical treatment, medication).

A number of strategies for ability to report to work involved seismic retrofitting, and was a cross-cutting theme for multiple factors. It was a strategy for Personal health and resources (ex. employee homes), Transit Barriers and Infrastructure impacts (ex. employee garages, public infrastructure), and Work-related Influences (ex. workplace building). The remote work strategy was another cross-cutting theme to address multiple factors, such as Transit Barriers and Infrastructure impacts, Work-related Influences, and Location. These are important findings as they highlight the types of strategies that can most efficiently target influential factors for reporting to work.

Some important and timely findings are the suggested strategies to ensure the workplace is operational after an earthquake in relation to the factor Work-related influences. Participants showed great concern and little confidence in their workplace buildings to withstand a catastrophic earthquake and suggested that workplaces be initially engineered to withstand shaking or the buildings be seismically retrofitted. These suggestions may be substantiated, for example, currently no state-owned office buildings in Oregon are designed and constructed to be operational after a Cascadia Subduction Zone earthquake (State of Oregon 2017). In early 2017, the State of Oregon initiated plans to build the first state-owned office buildings that will be self-sufficient (electricity generation, water, accommodations, etc.) and can withstand a Cascadia Subduction Zone earthquake (State of Oregon 2017), with the purpose of these buildings to house executive, legislative, and judicial branches of the State government. However, the Emergency Coordination Center for the State of Oregon will not be housed in these resilient buildings. As Work-related influences is an important factor in the ability of emergency managers to report to work and the creation of a workplace that can be operational after a catastrophic earthquake is suggested as a strategy to address this factor, it is paramount that governments prioritize the construction of resilient buildings housing emergency coordination centers.

Some strategies discussed to address ability to report to work for emergency managers are supported in previous research among healthcare workers. In this study, strategies to address Transit Barriers and Infrastructure impacts included employer provision of transportation to and from work, and a number of strategies employees could take on their own for transportation. Specific strategies addressed in previous literature include, for example a shuttle service, and pre-arranged carpool of employees (Stergachis et al. 2011). Although these strategies were not addressed specifically, they align with and complement the strategies suggested by participants to address Transit Barriers and Infrastructure impacts.

5.2.2 Strategies for factors influencing willingness to report to work

To address the factors influencing the willingness of emergency managers to report to work, participants provided a myriad of possible strategies. The lion’s share of strategies highlighted the perceived onus on the employer to be prepared and to prepare employees.

An interesting finding of this study is in the diversity of strategies, as they encompassed planning, training, and exercises for employees to increase the willingness of emergency managers to report to work—which are important aspects of the overall preparedness cycle in emergency management (Department of Homeland Security 2016). Of note, this study found that Family/Community Preparedness and Safety was the most important factor influencing the willingness of emergency managers to report to work, and numerous strategies were provided to address this factor. Participants suggested that employers require family plans of employees as a condition of employment, with additional strategies entailing employer-provided training on personal preparedness, and conducting an experiential activity (ex. emergency exercise) with family members to assess strengths and weakness of the family plans.

Previous research involving healthcare workers has documented the desire for more training on job roles in the event of an earthquake, as well as training on personal and family preparedness (Stergachis et al. 2011). Given this finding, it is recommended that employers focus on planning, training, and exercises as suggested strategies for this factor to ensure emergency managers are willing to report to work.

The factor Emergency Management Responsibility and Professionalism was the second most important factor overall in regard to willingness of emergency managers to report to work, and the most important for those from Washington. This was an intriguing finding on its own, but so also were the strategies to address this factor. Participants provided creative strategies that included cultivating a culture of excellence among emergency managers, creating and committing to a professional oath, and providing financial incentives for those who overcome obstacles to report to work. Previous research on healthcare workers supports the use of financial incentives as a strategy, as it was found to be the most influential in increasing willingness to report to work (Masterson et al. 2009). As a result, it is recommended that employers pursue financial incentives as a strategy. Overall, these intriguing findings that may warrant further research into professional and organizational culture as it relates to emergency management.

This study addressed both ability and willingness, and as a result was able to discover that multiple strategies suggested to address factors influencing ability to report to work can also carry over to address factors influencing willingness to report to work. A key example of this was strategies (ex. creating policies, plans, procedures, and mutual aid agreements) for employees to work at alternate locations in support of the overall response. In a study of willingness to report to work for healthcare workers after an earthquake scenario, 76% of respondents agreed that reporting to an alternate work location closer to their home would be helpful for reporting to work (Stergachis et al. 2011). This may be strategy worth prioritizing, as it addresses both factors influencing ability and willingness to report to work and is supported by previous research. In addition, strategies for ensuring employees and family were prepared (ex. creating a family emergency plan) addressed influential factors in both ability and willingness to report to work. This may be another area prioritized for implementing suggested strategies, as they would address both ability and willingness to report to work.

5.3 Limitations and strengths of study

As with any study, this study has specific limitations to address. First, this study focused on state-level emergency managers in Oregon and Washington. The generalizability to non-emergency managers, emergency managers at non-state levels (e.g., local and federal levels), and those outside Oregon and Washington is not known. Furthermore, the study utilized a catastrophic earthquake scenario. The extrapolation of study results to non-catastrophic earthquakes, as well as to other types of disaster (ex. influenza pandemic, terrorist attack, hurricane) is not known. The relatively small sample size was a limitation of the study. Although appropriate analyses were performed to account for small sample size, a larger sample would reduce the probability of committing a type 2 error. The smaller sample size may be due to the inability of the researcher to provide incentives, as there exist strict limitations in providing incentives with monetary value to the participants as government employees. The study also overlapped with a presidential declared disaster for the two states, which limited the availability of portions of the staff. This study may also be subject to social desirability bias, as participants could have been hesitant to provide information that would convey an inability and/or unwillingness to report to work. However, this bias was mitigated by ensuring study responses and participation were confidential, and response data was not tied to an individual.

This study also performed many analyses, and as such may increase the likelihood of a false positive (e.g., type 1 error) through multiple comparisons. The likelihood that groups being compared will differ by chance alone increases as the number of comparisons increases. Another limitation worth noting is that participant demographic characteristics in this study may differ from the underlying population of emergency managers in the Pacific Northwest – a potential sampling bias that would affect internal validity. In this study the demographic makeup of participants in the various data collection phases ranged from 52.9% to 66.7% male, a mean age from 47.2 to 49.4 years, 97% to 100% white, and 75.8% to 88.2% who have earned at least an associate’s degree. However, it should be noted that the demographic characteristics of the study’s sample are comparable to existing demographic research on emergency managers. In a recent large (n = 1058) nation-wide survey to determine demographics of emergency managers, 81% were male, 72% were older than 45 years of age, 94% were white, and 78% achieved at least an associate’s degree (Weaver et al. 2014).

Lastly, the extent to which the results are generalizable to regions or organizations with largely different demographic characteristics (ex. younger, less educational attainment, more racially diverse) is not known.

Despite the aforementioned limitations, this study has notable strengths. Of note, this study addressed a serious knowledge gap in research. To date, no prior study has addressed influential factors for ability and willingness for reporting to work for emergency managers. Emergency managers carry the important responsibility of coordination and management of personnel and resources throughout the disaster management cycle. As such, the focus on emergency managers is an important aspect of this research. Another major strength was the utilization of concept mapping to discover influential factors, and capture participant-generated strategies to address priority factors for reporting to work. The exposure of complex relationships between factors was aided by the structured and integrated mixed-method concept mapping process that employs both qualitative and quantitative components.

5.4 Path forward for future research and practice

This study provided important regional information to aid in the understanding of complexities within reporting to work for emergency managers after a catastrophic earthquake. Moreover, it also provided a myriad of strategies to assist future efforts in ensuring emergency managers are both able and willing to report to work. Future research will include determining the most effective dissemination channels for this information to ensure use by emergency managers. Future research is also needed to determine frequency of adoption of proposed strategies, and the effectiveness of strategies as they are implemented.

5.5 Conclusion

Emergency managers play a lead role in the health and safety of their communities, and will be critically important after a catastrophic disaster. Historical examples of disaster and existing research have indicated that those expected to report to work after a disaster may not be able and may not be willing to report to work. The factors influencing reporting to work after disaster are complex, and to date no research has examined the factors influencing the ability to report to work and willingness to report to work for emergency managers despite their pivotal role. Utilizing concept mapping, this study has identified multiple influential factors for ability to report to work and for willingness to report to work for emergency managers after a catastrophic natural disaster (e.g., 9.0 Cascadia Subduction Zone earthquake). Participants also proposed a number of tangible strategies to address priority factors, aiding in the utility of study results for the emergency management community. Future research is warranted to determine the effectiveness of proposed strategies as they are implemented, as well as to research influences for emergency managers in turning research into practice.

References

Adams L, Berry B (2012) Who will show up? Estimating ability and willingness of essential hospital personnel to report to work in response to a disaster. Online J Issues Nurs 17(2):469

Atwater BF (1987) Evidence for great Holocene earthquakes along the outer coast of Washington State. Science 236:942–944

Balicer RD, Omer SB, Barnett DJ, Everly GS (2006) Local public health workers’ perceptions toward responding to an influenza pandemic. BMC Public Health 6(99):1–8

Burke R, Goodhue C, Chokshi N, Upperman J (2010) Factors associated with willingness to respond to a disaster: a study of healthcare workers in a tertiary setting. Prehospital Disaster Med 26(4):244–250

Caracelli VW, Green JC (1993) Data analysis strategies for mixed-method evaluation designs. Eval Program Plan 12(1):45–52

Charney R, Rebmann T, Flood RG (2014) Working after a tornado: a survey of hospital personnel in Joplin, Missouri. Biosecur Bioterror 12(4):190–200

Cone DC, Cummings BA (2006) Hospital disaster staffing: if you call, will they come? Am J Disaster Med 1:28–36

Davidson JE, Sekayan A, Agan D, Good L, Shaw D, Smilde R (2009) Disaster dilemma: factors affecting decision to come to work during a natural disaster. Adv Emerg Nurs J 31(3):248–257

Di Maggio C, Markenson D, Loo GT, Redlener I (2005) The willingness of US emergency medical technicians to respond to terrorist incidents. Biosecur Bioterrorism Biodefense Strategy Practice Sci 3(4):331–337

Dulin-Keita A, Clay O, Whittaker S, Hannon L, Adams IK, Rogers M, Gans K (2015) The influence of HOPE VI neighborhood revitalization on neighborhood-based physical activity: a mixed- methods approach. Soc Sci Med 139:90–99

Federal Emergency Management Agency (2007). Principles of emergency management. https://training.fema.gov/hiedu/docs/emprinciples/principles%20of%20emergency%20management%20brochure.doc. Accessed on 1 Dec 2016

Federal Emergency Management Agency (2013). Continuity Guidance Circular 2. Continuity Guidance for Non-Federal Governments: Mission Essential Functions Identification Process (States, Territories, Tribes, and Local Government Jurisdictions) FEMA P-789. https://www.fema.gov/media-library-data/1386609058826-b084a7230663249ab1d6da4b6472e691/Continuity-Guidance-Circular2.pdf. Accessed on 23 Nov 2015

Federal Emergency Management Agency (2016). Cascadia Rising 2016 Exercise. Cascadia Subduction Zone (CSZ) Catastrophic Earthquake and Tsunami Functional Exercise: June 7-10, 2016. Joint Multi-State After-Action Report. https://www.fema.gov/media-library/assets/documents/128345. Accessed on 13 Oct 2016

Frankel, A.D., & Petersen, M.D. (2008). Cascadia subduction zone (No. 2007-1437-L). Geological Survey (US)

Fritz CO, Morris PE, Richler JJ (2012) Effect size estimates: current use, calculations, and interpretation. J Exp Psychol Gen 141(1):2

Gershon R, Magda L, Qureshi K, Riley H, Scanlon E, Torroella C, Richards R, Sherman M (2010) Factors associated with the ability and willingness of essential workers to report to duty during a pandemic. J Occup Environ Med 52(10):995–1003

Goldfinger C, Nelson CH, Morey AE, Johnson JR, Patton J, Karabanov E, Gutierrez-Pastor J, Eriksson AT, Gracia E, Dunhill G, Enkin RJ, Dallimore A, Vallier T (2012) Turbidite event history—methods and implications for Holocene paleoseismicity of the Cascadia subduction zone: U.S. Geological Survey Professional Paper 1661–F

Henry JF, Beals HK (1991) Juan Pérez on the Northwest Coast: Six Documents of His Expedition in 1774

Iwelunmor J, Blackstone S, Gyamfi J, Airhihenbuwa C, Plange-Rhule J, Tayo B, Adanu RMK, Ogedegbe G (2015) A concept mapping study of physicians’ perceptions of factors influencing management and control of hypertension in sub-Saharan Africa. Int J Hypertens

Kane M, Trochim WMK (2007) Concept mapping for planning and evaluation. Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks

Kruus L, Karras D, Seals B, Thomas C, Wydro G (2007) Healthcare worker response to disaster conditions. Acad Emerg Med 14(5S):S189–S189

Ludwin RS, Dennis R, Carver D, McMillan AD, Losey R, Clague J, Jonientz-Trisler C, Bowechop J, James K (2005) Dating the 1700 Cascadia earthquake: great coastal earthquakes in native stories. Seismol Res Lett 76(2):140–148

Mackler N, Wilkerson W, Cinti S (2007) Will first-responders show up for work during a pandemic? Lessons from a smallpox vaccination survey of paramedics. Disaster Manag Response 5(2):45–48

Masterson L, Steffen C, Brin M, Kordick MF, Christos S (2009) Willingness to respond: of emergency department personnel and their predicted participation in mass casualty terrorist events. J Emerg Med 36:43–49

McKnight PE, Najab J (2010) Mann-Whitney U Test. Corsini Encyclopedia Psychol

Mercer M, Ancock B, Levis J, Reyes V (2014) Ready or not: does household preparedness prevent absenteeism among emergency department staff during a disaster? Am J Disaster Med 9(3):221–232

Natan MB, Nigel S, Yevdayev I, Qadan M, Dudkiewicz M (2014) Nurse willingness to report for work in the event of an earthquake in Israel. J Nurs Manag 22:931–939

O’Campo P, Burke J, Peak GL, McDonnell KA, Gielen AC (2005) Uncovering neighbourhood influences on intimate partner violence using concept mapping. J Epidemiol Community Health 59(7):603–608

Ogedegbe C, Nyirenda T, DelMoro G, Yamin E, Feldman J (2012) Health care workers and disaster preparedness barriers to and facilitators of willingness to respond. Int J Emerg Med 5(29):1–9

Qureshi K, Gershon RRM, Sherman MF, Straub T, Gebbie E, McCollum M, Erwin MJ, Morse SS (2005) Healthcare workers’ ability and willingness to report to duty during catastrophic disasters. J Urban Health Bull New York Acad Med 82(3):378–388

Rosas SR, Kane M (2012) Quality and rigor of the concept mapping methodology: a pooled study analysis. Eval Program Plan 35(2):236–245

Sallis JF, Owen N, Fisher EB (2008) Ecological models of health behavior. Health Behav Health Educ Theory Res Pract 4:465–486

Shapira Y, Marganitt B, Roxiner I, Scochet T, Bar Y, Shemer J (1991) Willingness of staff to report to their hospital duties following an unconventional missle attack: a state-wide survey. Isr Med Sci 27:704–711

State of Oregon (2017) Department of Administrative Services. Oregon Resilience Buildings One and Two. Fact Sheet. Dated February 15, 2017

Stergachis A, Garberson L, Lien O, D’Ambrosio L, Sangaré L, Dold C (2011) Health care workers’ ability and willingness to report to work during public health emergencies. Disaster Med Public Health Prep 5:300–308

United States Department of Homeland Security (2016) Plan and Prepare for Disasters. https://www.dhs.gov/topic/plan-and-prepare-disasters. Accessed on 1 Dec 2016

Walker RE, Fryer CS, Butler J, Keane CR, Kriska A, Burke JG (2011) Factors influencing food buying practices in residents of a low-income food desert and a low-income food oasis. J Mixed Methods Res 5(3):247–267

Weaver J, Harkabus LC, Braun J, Miller S, Cox R, Griffith J, Mazur RJ (2014) An overview of a demographic study of United States emergency managers. Bull Am Meteor Soc 95:199–203

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Swick, Z.D., Baker, E.A., Elliott, M. et al. The Cascadia Subduction Zone earthquake: Will emergency managers be willing and able to report to work?. Nat Hazards 103, 659–683 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11069-020-04005-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11069-020-04005-9