Abstract

Five areas in Central Europe, each hosting abundant geological evidence of Carboniferous to Permian volcanic activity, are analysed in terms of their volcanism-related geoheritage and opportunities to develop geotourist product. One area is located in the eastern part of Germany (Geopark Porphyrland), two in northern Czechia (Bohemian Paradise, Broumovsko) and two in south-west Poland (Wałbrzych region, Land of Extinct Volcanoes). Four main geoheritage themes are identified: geology and palaeovolcanology, mineralogy, geomorphology, and heritage stone resources. Each of the regions considered in the paper may be characterized by its core geoheritage theme and secondary themes, less evidently exposed. These themes are optimal foundations to develop geo-interpretation and geotourism. Challenges include difficulties in relating rock record to long eroded volcanic landforms, provision of adequate solutions for mineral collectors and proper conservation of quarries which offer best insights into the history of volcanic processes from c 300 Ma ago.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Volcanism is among the most popular subjects in geotourism and geoeducation, exploited in numerous regions and localities worldwide (see recent overviews by Erfurt-Cooper and Cooper 2010, Erfurt-Cooper 2014). Of particular importance and appeal are sites and areas where volcanic and hydrothermal processes can be safely witnessed and these attract tourists at the global scale (e.g., Hawaii and Japan—Erfurt-Cooper 2011, Iceland—Ólafsdóttir and Dowling 2013, New Zealand—Migoń and Pijet-Migoń 2017). In addition, extinct but geologically recent volcanism, dated back to the Neogene-Quaternary timespan and represented by abundant rock record and diverse volcanic landforms, is also or may become a foundation for successful promotion of geoheritage through tourism and education. Numerous examples can be found in Europe (Cayla 2014; Rapprich et al. 2017; Szepesi et al. 2017) and North America (Erfurt-Cooper 2011), as well as in East Asia (Gao et al. 2013; Woo et al. 2013; Aquino et al. 2017), Australia (Joyce 2010), Africa (Megerssa et al. 2019; Tefogoum et al. 2019) and South America (Gałaś et al. 2018). The importance of volcanic phenomena in the global geoconservation context is exemplified by their prominent presence on the World Heritage List of UNESCO (Wood 2009; Casadevall et al. 2019), within the Global Geoparks Network (Liu et al. 2012; Brilha 2018) and among national inventories of sites of special geoscience interest (e.g. Joyce 2009).

By contrast, geologically ancient volcanism appears to generate much less attention, unless it features certain visual characteristics which are immediately noticed, even by a casual visitor. The prime example of this is Giant’s Causeway site in Northern Ireland, a UNESCO World Heritage property since 1986, distinguished by its perfectly regular columnar jointing exposed within shore platforms and steep cliffs (Crawford 2016). Otherwise, ancient volcanic heritage as a resource for geo-activities is explored at national or regional level, as just one more component of geological record, but remains rather poorly known internationally. Nonetheless, specific examples show considerable potential of such areas. Yandangshan UNESCO Global Geopark in Zhejiang, China, reveals the history of silicic volcanism in the Cretaceous that produced a large caldera and left a rock record now exposed in magnificent scenery of high rhyolite lava and ignimbrite cliffs (Tao et al. 2008). A related theme explored in Yandangshan is the use of stone resources, and the history of rhyolite quarrying is presented at impressive underground quarries in Changyu town.

In this paper, we intend to explore geoheritage aspects and geotourism potential of a few regions in Central Europe (Germany, Czechia, Poland) linked by a Late Palaeozoic volcanism theme. The area preserves the geological record of large-scale volcanic activity from Late Carboniferous and Early Permian times, directly exposed in numerous quarries, both operational and abandoned, and indirectly in landforms originated due to long-term weathering and erosion of volcanic rocks. It is also known for high-class mineralogical findings and widespread use of building stone resources. Despite general geographical proximity, the post-Permian geological evolution of each area followed a different pathway, resulting in dissimilar core values of local geoheritage. These, in turn, dictated area-specific opportunities for geoheritage promotion and geotourism development, not yet fully exploited. To this end, some suggestions for further actions will be offered. The specific regions considered in this paper are Geopark Porphyrland in Germany, part of UNESCO Global Geopark Bohemian Paradise and part of National Geopark Broumovsko in northern Czechia, an aspiring Geopark Land of Extinct Volcanoes and the surroundings of the city of Wałbrzych in south-west Poland.

Geological Context of Late Palaeozoic Volcanism and General Characteristics

Late Palaeozoic volcanism in Central Europe, partly visible in the exposed rock record and partly concealed under younger sediments, is related to the late stages of Variscan orogeny, typified by post-collisional extension (Hoffmann et al. 2013; Awdankiewicz et al. 2014b). These occurred in two separate phases (Hoffmann et al. 2013). The older one is dated for the Westphalian epoch of the Carboniferous (c 315–305 Ma), whereas the younger phase took place in the Asselian epoch of the Permian (c 300–290 Ma). Volcanic activity affected terrains of different geology and contemporaneous landscape, resulting in contrasting styles of magma emplacement and rock record. In large intramontane basins, filled over time by thick packages of sediments, subvolcanic intrusions were common, with laccoliths, domes, and sills, although surface manifestations of volcanism occurred too. For Variscan basement areas, voluminous extrusions of ignimbrites were characteristic and large calderas were produced. In terms of lithology, various rock types are exposed, from silicic to intermediate-mafic, but rock inventories vary from area to area. For example, the volcanic succession of the Intra-Sudetic Basin contains rhyolites, rhyodacites, andesites, trachyandesites, and basalts (Awdankiewicz 1999a, b), whereas the North Saxon Volcanic Complex is dominated by silicic volcanism, with rhyolite lavas and ignimbrites (Repstock et al. 2018).

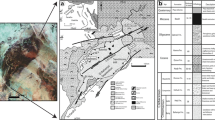

The areas selected for this study are located within four geological units of Central Europe, all inside the Saxo-Thuringian Zone of the Variscan orogeny. These are (Fig. 1a):

North Saxon Volcanic Complex (Hoffmann et al. 2013; Breitkreuz 2016), where Geopark Porphyrland was established (Fig. 1b)

Krkonoše Piedmont Basin (Ulrych et al. 2002, 2006; Stárková et al. 2011; Opluštil et al. 2016), the western part of which is included into the Bohemian Paradise UNESCO Global Geopark (Fig. 1c)

Intra-Sudetic Basin (Awdankiewicz 1999a, b, 2004; Ulrych et al. 2004), where the neighbouring National Geopark Broumovsko and the Wałbrzych region are located (Fig. 1d)

North-Sudetic Basin (Awdankiewicz et al. 2014b), the eastern termination of which falls within the boundaries of the Aspiring Geopark Land of Extinct Volcanoes

Study Areas

Geopark Porphyrland

Geopark Porphyrland is one of national geoparks in Germany, situated in the State of Saxony, east and south-east of the city of Leipzig. It encompasses c 1200 km2 and extends along the river Mulde (Fig. 1b). Early Permian volcanic rocks crop out extensively in the Geopark. They are mainly of rhyolitic composition and represented by lavas, dykes, tuffs and ignimbrites. Collectively, they form the largest outcrop of Palaeozoic eruptive rocks in Central Europe, covering some 2000 km2. Large volumes and considerable areal extent of these rocks were interpreted in terms of two large volcanic centres: Wurzen caldera in the north, c 40 km wide, and Rochlitz caldera in the south, c 60 km wide (Breitkreuz 2016). Despite this extensive outcrop area, geomorphic expression of volcanic rocks is rather poor. Bedrock hills are only c 100 m high and slope inclinations are low, seldom above 15°. There was apparently some contribution of ice sheet erosion during the Pleistocene to the lowering of the elevations (Geißler and Heidenfelder 2016). The region is long famous as a quarrying centre, and local rhyolites were highly appreciated for their building and ornamental stone qualities (Siedel 2016). Consequently, quarries are numerous and many continue to operate. Geopark Porphyrland includes 18 designated geosites, with three of them classified as of national significance. The vast majority of these geosites addresses volcanism as a theme (Geißler et al. 2019).

Bohemian Paradise UNESCO Global Geopark

Bohemian Paradise European Geopark was established in 2005 and became a UNESCO Global Geopark in 2015. It covers geologically highly diverse and geomorphologically very scenic area in northern Czechia (Mertlik and Adamovič 2016). Bohemian Paradise (Český raj in Czech) has been a most popular tourist destination since the mid-nineteenth century, but visitations were mainly focused on sandstone rock cities and other outcrops of Cretaceous sedimentary rocks (Adamovič et al. 2006; Kołodziejczyk 2020). Among the reasons to create a Geopark on a larger area were the intentions to expose other aspects of regional geoheritage and to diversify tourist flows. In the north-eastern part of the Geopark outcrops of Permian volcanic rocks are widespread, predominantly basalts to trachybasalts (‘melaphyres’ in older terminology) (Ulrych et al. 2002; Stárková et al. 2011) (Fig. 1c). In comparison with striking landforms developed upon Cenozoic basalts in northern Czechia, their geomorphic expression is poor to moderate, although some elevations reach nearly 700 m a.s.l. Natural rock outcrops are scarce, but numerous quarries exist, some being famous as mineralogical localities. Agate and jasper are most characteristic for the area, with impressive collections exhibited in local museums.

Broumovsko National Geopark

Broumovsko National Geopark was recently established (2018) in the Czech part of the Intra-Sudetic Basin in the Middle Sudetes, partially overlapping with the existing Landscape Protection Area Broumovsko. It includes outcrops of sedimentary and volcanic rocks spanning the Carboniferous-Cretaceous interval, with the Cretaceous rocks being associated with the most impressive rock erosional scenery (Vítek 2016) and attracting the vast majority of visitors. Volcanic rocks, mainly rhyolite tuffs and trachyandesites of Early Permian age (Tásler 1979; Ulrych et al. 2004; Opluštil et al. 2016), occur along the Czech-Polish border in a narrow, usually less than 3 km wide belt (Fig. 1d). This belt coincides with the Javoří hory mountain ridge (max elevation 884 m a.s.l.), with relative relief up to 300 m. Quarrying occurred locally and large natural rock outcrops within regolith-covered slopes are few.

Wałbrzych Region

Late Carboniferous and Permian volcanic rocks in the vicinity of Wałbrzych city in SW Poland, in the Middle Sudetes, are part of the same volcano-sedimentary succession of the Intra-Sudetic Basin that is present in the National Geopark Broumovsko in Czechia (Fig. 1d). However, their extent in Poland is larger, lithology is more diverse and geomorphological expression is more variable. Moreover, different organizational structures in Czechia and Poland, with a National Geopark in the former and no specific geoheritage-oriented initiatives in the latter, justify separate treatment. Rhyolites, trachyandesites, trachybasalts and rhyolitic tuffs are present, testifying to the multi-phase volcanic activity (Awdankiewicz 1999a, b, 2004). Both eruptive and subvolcanic rocks occur. In terms of geomorphology, both larger mountain massifs and isolated rhyolite dome-shaped hills occur, reaching 300–400 m high (936 m a.s.l. maximum), and relief is very steep along the contact with sedimentary rocks of broadly the same age. Industrial exploitation of volcanic rocks was limited, although a few large quarries are active nowadays. Part of the volcanic rock outcrop area is within the boundaries of Landscape Park “Sudety Wałbrzyskie” protected zone, with a few sites having the status of nature monument. The potential for geotourism and geoeducation was preliminarily assessed some years ago (Ihnatowicz et al. 2011), but the study was focused almost solely on geological outcrops.

Land of Extinct Volcanoes Aspiring Geopark

The area branded as the Land of Extinct Volcanoes is located in the north-western part of the Sudetes in SW Poland and integrates geological evidence of different volcanic periods, spanning from the Early Palaeozoic to the Neogene (Pijet-Migoń and Migoń 2019). Geologically, it covers partly the basement unit of the Kaczawskie Mountains zone and partly the North-Sudetic Basin which is a late Variscan and post-Variscan sedimentary basin (Fig. 1a). As in the Wałbrzych region, both silicic and intermediate volcanic rocks are preserved, chiefly rhyolites and trachybasalts, representing a few distinct eruptive cycles (Awdankiewicz et al. 2014b). Geomorphic expression is less conspicuous than in the Intra-Sudetic Basin, with the height of individual elevations not exceeding 150 m (max elevation up to 500 m a.s.l.). The area is long known for the abundance of gemstones, mainly agates, collected since the nineteenth century. Geoconservation status of Permian volcanic outcrops is low, with only one former quarry designated as nature monument. In the context of geotourism promotion, Palaeozoic volcanism is clearly overshadowed by much younger, Oligocene to Miocene volcanism, also present in this region. The regional development strategy foresees an application to the UNESCO Global Geopark Network in the near future (Pijet-Migoń and Migoń 2019).

Facets of Late Palaeozoic Volcanic Geoheritage and How They Are Presented and Exploited

Geology, Lithological Diversity and Paleovolcanic Reconstructions

Rock outcrops, whether natural or artificial, are the best places to examine geology of an area and spatiotemporal relationships between different rock complexes. In ancient volcanic terrains, they also allow for the reconstruction of history of volcanic activity and the recognition of types of eruptive processes, otherwise not possible because of considerable surface erosion and obliteration of original volcanic structures. Such outcrops, especially if sufficiently large and complex, provide the best opportunities to develop geotourism and geoeducation. However, in the areas studied within this paper, such natural outcrops are not many, and hence, the insights they offer are site-specific. Their role may be replaced by quarries, but there are various constraints limiting their use too, especially if they are still working (which is often the case in areas considered here).

Large quarries open for viewing to the public are in Geopark Porphyrland, but the sheer size of volcanic explosions resulted in rather monotonous rock records visible at the quarry-scale. At Rochlitzer Berg, a few very big quarries are connected by an educational trail (Auf den Spuren des Rochlitzer Porphyrs 2008), but only one lithological unit—a thick package of macroscopically little diversified ignimbrite—is exposed (Fig. 2a). Further disused quarries in the area, included in the list of geosites (Geißler et al. 2019), expose rhyolite ignimbrites and lavas, but in one case only (Steinbruch am Wolfsberg), more than one lithology can be seen. In the Broumovsko National Geopark, a few rather small natural outcrops of volcanic rocks are included into the web-based guide to sites of geological interest, showing all main rock types in the area (https://geopark.broumovsko.cz/geologicke-lokality1; access date 31-10-2019; Fig. 1d), but the best exposure is a disused part of Rožmitál quarry, where andesitic lava flows and various pyroclastic deposits can be seen, recently documented by Awdankiewicz et al. (2014a) (Fig. 2b). An educational path was built in the quarry, to show representative sections. Likewise, in the Bohemian Paradise UNESCO Global Geopark, natural outcrops are scarce and quarries are the only means to see larger sections. However, some localities considered as geosites in the database of the Czech Geological Survey and extensively documented in scientific literature (Stárková et al. 2011) are off-limits to individual visitors, being located in working quarries or on private properties (Fig. 2c). The Votrubcův lom (quarry) at Kozákov hill (Figs. 1c and 3a) is the only accessible locality of large size, but it is mainly a mineralogical locality, whereas a geological section consisting of multiple lava flows (Fediuk 2001) is not explained on site.

Geology of Permian volcanic formations. a Thick, but rather monotonous package of ignimbrites at Rochlitzer Berg (Seidelbruch quarry), Geopark Porphyrland. b Alternating andesitic lava flows and pyroclastic successions in the quarry of Rožmitál, Broumovsko. c Lava flow overlain by scoriaceous-tuff breccia in the Hvězda quarry near the town of Nová Paka, Bohemian Paradise. d Columnar jointing in rhyolites at Mt Wielisławka, Land of Extinct Volcanoes

Mineralogical heritage of Bohemian Paradise UNESCO Global Geopark. a Votrubcův lom quarry is the famous and accessible locality which yields high-quality specimens. Steeply inclined sequence of lava flows is seen in the quarry wall. b Mineralogical part of exhibition in the regional museum in Nová Paka

In the Land of Extinct Volcanoes, both natural exposures and quarries are rare, but one locality stands out due to its fan-shaped arrangement of columnar jointing exposed in an old rhyolite quarry (Fig. 2d). This locality was declared a nature monument already in the first half of the twentieth century and retains this status until today, although on-site interpretation is rather rudimentary. In the Wałbrzych area, natural outcrops are more common and quarries are numerous, some extensively documented in scientific literature (Awdankiewicz 1999a) and included into the local geosite inventory (Ihnatowicz et al. 2011), but their potential for geotourism is yet to be fully exploited.

Mineralogical Heritage

Palaeovolcanic rocks often host various minerals which crystallized from fluids penetrating into fissures, pores and vesicles left after solidification of magma. Some of Central European palaeovolcanic regions have long been known for their rich mineralogical heritage. This is particularly true for the Bohemian Paradise UNESCO Global Geopark, where a number of rich mineralogical localities have been exploited since the Middle Ages. Mineral collecting is still a popular activity among both casual tourists, as well as professional collectors. The Votrubcův lom quarry is privately owned, and searching the talus and old spoil tips is permitted by the owner (Fig. 3a). The most common minerals (gemstones) are agates in a variety of types and jasper (Hromádko n.d.). The regional mineralogical heritage is presented in museums in Nová Paka (Fig. 3b) and Turnov, at local exhibitions in smaller towns, as well as in private collections.

Mineralogy is a theme explored also in the Land of Extinct Volcanoes. Both rhyolites and trachybasalts host agates, and these have been searched for since the nineteenth century, both in quarries, road and railway cuts into solid volcanic rocks, as well as within regolith where shallow excavations are made. The latter have resulted in considerable land degradation in the most popular places (Niebrzydowska and Remisz 2012), but no efficient countermeasures have been implemented so far. In contrast to the Bohemian Paradise, no permanent museum dedicated to mineralogy exists in the area, but temporary exhibitions are organized, particularly in connection with annual events such as ‘Lwówek Agate Summer’ show.

Geomorphology

Geomorphological heritage within ancient volcanic terrains considered in this paper is displayed in at least five settings: (a) as a direct reflection of eruptive and intrusive processes; (b) as the evidence of long-term differential erosion which accentuated the presence of volcanic rocks; (c) specific geomorphic features are the legacy of cold-climate (periglacial) processes during the Pleistocene; (d) some volcanic outcrops have been overridden by the continental ice during Quaternary glaciations, which left tangible evidence; (e) locally, other distinctive surface processes occurred, for which volcanic rocks provided the necessary underpinning.

The protracted timespan that elapsed since the volcanic activity effectively precludes the survival of original volcanic landforms. Calderas of Rochlitz and Wurzen in Geopark Porphyrland are considered some of the greatest in Central Europe and the magnitude of explosions is inferred to be M = 8.4 (Breitkreuz 2016), but the contemporary morphology of the region provides no clues to their former location and size. Likewise, extensive volcanic rock outcrops in the Bohemian Paradise UNESCO Global Geopark and the Broumovsko Geopark cannot be directly linked to any original landforms from the Permian times and reconstructed palaeovolcanic landscapes are very different from those of today (e.g. Awdankiewicz et al. 2014a). However, some isolated rhyolite hills in the Wałbrzych region and the Land of Extinct Volcanoes are interpreted as not very different from the original volcanic structures and the rationale for their survival was rapid burial by clastic sediments, as shown for large volcanic bodies in Central European lowland (Geißler et al. 2008). Nowadays, they crop out adjacent to the volcanic rocks. Finally, some magmatic bodies are interpreted as subvolcanic sills, dykes and laccoliths (Fig. 4a) (Awdankiewicz 1999a).

Landforms associated with Carboniferous and Permian volcanic rocks. a Rhyolite dome-shaped hills in the vicinity of Wałbrzych (Poland). b Javoří hory ridge along the Czech-Polish border (left) are built of resistant volcanic rocks and overlook a wide intramontane trough excavated in sedimentary formations. c Periglacial block field at Mt Dłużyca in the Land of Extinct Volcanoes. d Rocky head scarp of a landslide and extensive screes in the Kamienne Mountains, Wałbrzych region

The clear geomorphological expression of Carboniferous and Permian volcanic rocks in the Intra-Sudetic Basin (Broumovsko, Wałbrzych) is mostly the result of differential erosion during the Cenozoic (Placek 2011; Migoń et al. 2017). The strength of massive volcanic bedrock is considerably higher than that of the surrounding sedimentary formations which include conglomerates, heterolithic sandstones, mudstones and claystones. In effect, not only does local relief exceed 300 m but the steepness of slopes is considerable along lithological contacts, up to 40° (Fig. 4b). Local differences in rock strength account for the presence of rock spurs and ravines within steep rhyolite slopes. Similar relationships can be found in the Land of Extinct Volcanoes and the Bohemian Paradise, although in both of them, topography is more subdued, and slopes are less steep.

The legacy of the Quaternary varies from area to area. Of particular significance are outcrops of rhyolites in Geopark Porphyrland which bear evidence of glacial erosion in the form of smoothed surfaces, glacial striations and, possibly, remoulding of the hill shapes towards asymmetrical roche mountonnées (Geißler and Heidenfelder 2016) (Fig. 5a). Localities such as Spielberg and Kleiner Berg are among the designated geosites (geotops), with the latter having the status of ‘National Geosite’ (Fig. 5b). It is possible that the subdued relief of once mighty volcanoes is partly the result of glacial erosion during the Elsterian glaciation (Marine Isotope Stage 12). Volcanic outcrops in the Land of Extinct Volcanoes were overridden by the ice sheet at the same time too, but unequivocal glacial imprint has not been recognized. Periglacial processes, by contrast, were ubiquitous in the extraglacial zone and active throughout the Pleistocene, but their legacy is rather surprisingly scarce. Occasional rock cliffs and rare angular block fields (Fig. 4c) are probably inherited from the Pleistocene (Traczyk 2011); otherwise, continuous weathering towards inconspicuous regolith cover took place.

A distinguishing feature of the Permian volcanic terrain south of Wałbrzych is the widespread occurrence of palaeolandslides. The key reasons for their presence are lithological and structural, particularly the juxtaposition of massive and strong volcanic rocks in the upper slope with much weaker sedimentary formations in the lower slope. This variety of mass movements in the area has been extensively documented elsewhere and the key localities include Rogowiec, Suchawa and Lesista Wielka (e.g., Migoń et al. 2010, 2017; Kasprzak et al. 2016, 2019). Landslide terrains are associated with a number of minor distinctive features of interest, such as tall rock cliffs, scree slopes, boulder streams from rock avalanches and open clefts (Fig. 4d). In addition, head scarps of landslides allow examination of the lithology of volcanic rocks. Landslides are also known from localities in the Land of Extinct Volcanoes (Kowalski and Wojewoda 2018). In the remaining regions, large landslides have not been documented which may be related to lower relative relief and insufficient slope inclination, as well as to unfavourable lithological conditions.

Stone Industry

Volcanic rocks have long been used for commercial purposes, but the history of the stone industry is particularly protracted and rich in Geopark Porphyrland (Siedel et al. 2019). It dates to the twelfth century and the local stone, mainly ignimbrite (‘Porphyrtuff’), was used to build medieval castles and churches (Fig. 6a), as well as to dress millstones. Subsequently, the range of uses increased and the ‘Rochlitzer Porphyrfuff’ in particular has become famous well beyond the region (Siedel 2016; Siedel et al. 2019). It was used, among others, to build the Battle of Nations monument in Leipizig (Fig. 6b), commemorating the 1813 battle, and considered the largest construction of its kind. Numerous quarries are the evidence of high rock quality and sustained demand for local stone. They have also become impressive landmarks such as those on the Rochlitzer Berg (Fig. 6c) or in Beucha (Fig. 6d). In the former locality, an educational trail connecting different quarries and some of the technical infrastructure that survived was designed to show the legacy of stone industry (Auf den Spuren des Rochlitzer Porphyrs 2008).

Stone heritage in Geopark Porphyrland. a Late Romanesque abbey church in Wechselburg was built mainly from Rochlitzer Porphyrtuff (ignimbrite). b Battle of Nations monument in Leipzig was built mainly from stone quarried in Beucha. c Gleisbergbruch quarry—the deepest quarry on Rochlitzer Berg. d Old quarry in Beucha, overlooked by a church whose foundations go back to medieval times, is a geosite of national importance

No comparable examples of widespread use of Palaeozoic volcanic rocks for building purposes are available from other areas, whereas the recent intensification of quarrying is the response to demand from road construction activities. However, in a few places, such as at Tatobity village in the Bohemian Paradise, past stone industry is recalled by means of an open-air exhibition in a former local quarry.

The Legacy of Palaeozoic Volcanism for Tourists—What to Focus on?

The above presentation of specific areas and the review of their geoheritage values shows that despite very similar geological foundation, each region is distinctive in terms of their core assets, and duplication among them is limited (Table 1).

The strengths of particular areas seem fairly well realized by stakeholders involved in geoconservation, geoheritage promotion and geotourism development, although performance in specific regions varies (Table 2). One has to note, however, that Geopark Porphyrland and Bohemian Paradise UNESCO Global Geopark have relatively long history of more than 10 years, whereas Broumovsko Geopark and the Land of Extinct Volcanoes aspiring geopark are more recent initiatives. Finally, for the Wałbrzych region, a preliminary assessment from geological point of view was attempted (Ihnatowicz et al. 2011), but there was hardly any follow-up.

In Geopark Porphyrland, the stone heritage is clearly exposed and it is notable that among eighteen designated geosites as many as nine are located in disused quarries. At Rochlitzer Berg, the geology of eruptions is presented as a side theme on the quarry trail rather than become the main subject. Focus on the use of mineral resources is the distinguishing feature of Geopark Porphyrland in general, since some of Geopark information centres are dedicated to kaolin and brown coal mining, also present in the area. General geology is explained indoor, at interpretation centres, rather than in the field. In the Bohemian Paradise mineralogical heritage is promoted through museums and exhibitions, whereas other aspects of Permian volcanic heritage are more difficult to be presented to the general public, both because of insufficient clarity of landscape expression and access issues. In the Broumovsko National Geopark, seven geosites within the volcanic terrain are listed, focusing mainly on rock types present at particular localities. Information about these geosites is available online only (www.geopark.broumovsko.cz; access date 2020-03-15). In the Land of Extinct Volcanoes Permian, volcanism is presented alongside Early Palaeozoic and Oligocene/Miocene volcanism, with the latter being more distinctive in the landscape. Hence, the current focus on mineralogy—similar to the Bohemian Paradise—seems a good choice, given its additional educational values (engaging activities, link to stone use by humans, encounters with local people during guided tours and workshops).

For the Wałbrzych region, the core asset seems to reside in impressive geomorphology, unique among all areas considered here in terms of both relief/steepness and landform inventories. This aspect was overlooked by Ihnatowicz et al. (2011) who identified 149 potential geosites in the area, among which only four were directly related to geomorphology and another six were classified as viewing points.

Challenges and Opportunities

Although volcanism is a very attractive subject for the general public, capable of generating considerable interest and hence, substantial benefits to past or present volcanic areas provided by tourist visitations (Erfurt-Cooper 2014), it is not necessarily easy to design the geotourist product based on these resources. This is particularly true for areas affected by volcanic activity in distant geological past, such as those considered in this study.

Basing on the experience and performance in the study areas, several challenges for successful promotion of the ‘ancient volcanism’ theme may be identified. First, the rock record may be relatively monotonous in viewing, hence not particularly suitable to build exciting stories for the visitors. Paradoxically, the more awesome and grand-scale the volcanic activity itself, the less diverse is the rock record to be seen at particular localities, as aptly exemplified by lava and ignimbrite outcrops in Geopark Porphyrland. By contrast, lithologically diverse outcrops such as in Rožmitál near Broumov or Hvězda near Nová Paka allow reconstruction of the volcanic activity that occurred at rather local scale, as singular monogenetic volcanoes. Second, storytelling cannot be based on relating process to effect, at least in most cases. This is because volcanic edifices have long been eroded, and the contemporary pattern of rock distribution typically has little in common with volcanic morphology from the Carboniferous and Permian times. Again, Geopark Porphyrland provides a good example, where calderas due to massive explosions in the Early Permian, tens of kilometres across, have been completely obliterated. Subvolcanic bodies better preserve the original shape of an intrusion, but the entire process of emplacement may be more difficult to comprehend.

Mineralogy is a theme exploited by tourism industry in some areas, and it has big potential as an engaging activity for different generations of visitors, but is not without problems. Gemstone collection is considered controversial in geoheritage and geoconservation (see Gray 2013; De Wever and Guiraud 2018), and trade is explicitly banned within UNESCO Global Geoparks. Although mineral collecting is regulated by the relevant legal acts in different countries, they are not necessarily obeyed and implementation may be difficult. In the Land of Extinct Volcanoes, some famous mineralogical localities were affected by considerable land degradation due to uncontrolled digging and excavation in weathered mantles, including the use of heavy machinery. There are associated safety issues as well.

In the temperate humid environment of Central Europe, vegetation spread is fast and natural rock outcrops are few. Thus, quarries offer the best insights into architecture of former volcanic structures. From this perspective, it is fortunate that the long history of stone use left many quarries which can be used to develop geo-interpretation. However, while working quarries are generally inaccessible, the abandoned ones require appropriate rehabilitation plans to ensure that their scientific and educational values survive and visitations are safe. Uncontrolled vegetation succession, planned reforestation, and conversion into landfill sites are direct threats that such localities are facing. Selling to private owners may put a geologically valuable site off-limits. Conservation plans for abandoned quarries and for those to be shortly closed down should become a priority.

Examination of individual areas allowed us to identify their core and secondary geoheritage values. Whereas the former are fairly well realized and there are various interpretation activities focused on them, others often remain neglected. However, by learning from good practices elsewhere, they should be seen as opportunities for further development of geoconservation, geoeducation, and geotourism. Historical stone industry creates a good link between natural resources and human use, and its potential should be evaluated in Broumovsko Geopark and Land of Extinct Volcanoes in particular. Similarly, old traditions of collecting, cutting and polishing minerals and rocks are worth further exploration in areas other than the Bohemian Paradise. Geomorphology of ancient volcanic terrains in the Sudetes is virtually unexplored in geoheritage context and although it is not directly related to Carboniferous and Permian volcanic landforms, it provides a good framework to look closely at the rocks themselves and to assess their strength and hardness. It was also observed that causal links between volcanism and mineralogy are insufficiently explored in geo-interpretation, which may be partly related to uncertainties in scientific explanation, and analogies to contemporary volcanism are rarely shown at geosites.

Finally, the development of Palaeozoic volcanism sites for geotourism may contribute to the diversification of tourist flows, especially in congested areas of Bohemian Paradise and Broumovsko. In both, rock cities and canyons cut in Cretaceous sandstones are the main attractions (Mertlik and Adamovič 2016; Vítek 2016) whereas nearby volcanic terrains are little visited. Recent initiatives to include these areas into respective Geoparks are a good step forward, but they need to be followed by investment in interpretative infrastructure at selected geosites, to provide an attractive alternative.

Conclusions

Given the considerable interest in contemporary volcanism within geotourism and frequent use of the legacy of late Cenozoic volcanism to develop geo-interpretation and to build tourist product, it is rather surprising that geoheritage aspects of Late Palaeozoic volcanic activity are largely neglected. In Central Europe, where the evidence of late Variscan volcanic activity is quite abundant, Geopark Porphyrland in east Germany is the only project that explores this theme as the leading one. In the remaining areas considered in this paper, ancient volcanism is presented alongside other geoheritage values and is overshadowed by these. Nevertheless, several sub-themes can be developed for geo-interpretation and geotourism, including geology and palaeovolcanology, subsequent landscape change and the role of volcanic rocks in Quaternary and contemporary geomorphology, mineralogical heritage and use of volcanic rocks as stone resources.

Examination of five areas selected for this study allowed us to identify primary geoheritage values (Table 1), well documented by scientists and most visible to the visitors, which are best suited to develop interpretation programmes. They include stone heritage and use in Geopark Porphyrland, mineralogy in the Bohemian Paradise and Land of Extinct Volcanoes, geology in the National Geopark Broumovsko and geomorphology in the Wałbrzych region. Secondary values may be developed following good practice implemented elsewhere but may need further research to fully realize their potential. Differences between the areas, despite location in geographical proximity and in similar geological setting, arise to a large extent from different pathways of geological evolution after the Permian. They favoured preservation of certain aspects of geoheritage, some at the expense of the others. Strategies for geotourism and geo-interpretation development should take these region-specific features into account, whereas networking and partnerships among the localities are able to complete the picture and provide wider context. A joint project to connect these different areas to tell a broader story of Palaeozoic volcanism is certainly an option to explore.

References

Adamovič J, Mikuláš R, Cílek V (2006) Sandstone districts of the Bohemian Paradise: emergence of a romantic landscape. Geolines 21:1–100

Aquino RS, Schänzel HA, Hyde KF (2017) Analysing push and pull motives for volcano tourism at Mount Pinatubo, Philippines. Geoheritage 9:1–15

Auf den Spuren des Rochlitzer Porphyrs (2008). Große Kreisstadt Rochlitz, Rochlitz

Awdankiewicz M (1999a) Volcanism in a late Variscan intramontane trough: Carboniferous and Permian volcanic centres of the Intra-Sudetic Basin, SW Poland. Geol Sudetica 32:13–47

Awdankiewicz M (1999b) Volcanism in a late Variscan intramontane trough: the petrology and geochemistry of the Carboniferous and Permian volcanic rocks of the Intra-Sudetic Basin, SW Poland. Geol Sudet 32:83–111

Awdankiewicz M (2004) Sedimentation, volcanism and subvolcanic intrusions in a late Palaeozoic intramontane trough (the Intra-Sudetic Basin, SW Poland). In: Breitkreuz C, Petford N (eds) Physical Geology of High-Level Magmatic Systems, Geol Soc London, Spec Publ, vol 234, pp 5–11

Awdankiewicz M, Awdankiewicz H, Rapprich V, Stárková M (2014a) A Permian andesitic tuff ring at Rožmitál (the Intra-Sudetic Basin, Czech Republic) – evolution from explosive to effusive and high-level intrusive activity. Geol Quart 58:759–778

Awdankiewicz M, Kryza R, Szczepara N (2014b) Timing of post-collisional volcanism in the eastern part of the Variscan Belt: constraints from SHRIMP zircon dating of Permian rhyolites in the North-Sudetic Basin (SW Poland). Geol Mag 151:611–628

Breitkreuz C (2016) Die Vulkanite and Subvulkanite im Geopark Porphyrland: Ein spätpaläozoischer Supervulkankomplex! Schriftenr Dt Gesell Geowiss 88:67–72

Brilha J (2018) Geoheritage and Geoparks. In: Reynard E, Brilha J (eds) Geoheritage. Assessment, Protection, and Management. Elsevier, Amsterdam, pp 323–335

Casadevall TJ, Tormey D, Roberts J (2019) World Heritage volcanoes. Classification, gap analysis, and recommendations for future listings. IUCN, Gland, Switzerland: viii + 68pp. https://doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.CH.2019.07.en

Cayla N (2014) Volcanic geotourism in France. In: Erfurt-Cooper P (ed) Volcanic Tourist Destinations. Springer, Dordrecht, pp 131–138

Crawford K (2016) A geoheritage interpretation case study: the Antrim Coast of Northern Ireland. In: Hose T (ed) Geoheritage and Geotourism. A European Perspective. Boydell Press, Woodbridge, pp 205–217

De Wever P, Guiraud M (2018) Geoheritage and museums. In: Reynard E, Brilha J (eds) Geoheritage. Assessment, Protection, and Management. Elsevier, Amsterdam, pp 129–145

Erfurt-Cooper P (2011) Geotourism in volcanic and geothermal environments: playing with fire? Geoheritage 3:187–193

Erfurt-Cooper P (2014) Volcanic Tourist Destinations. Springer, Heidelberg – Dordrecht

Erfurt-Cooper P, Cooper M (2010) Volcano and Geothermal Tourism. Sustainable Geo-Resources for Leisure and Recreation. Earthscan, London

Fediuk F (2001) Spodnoautunské vulkanity Kozákova, severní Čechy (Engl. Summ. Early Autunian volcanics of the Kozákov-hill, N-Bohemia). Zpr geol výzk v roce 2001:27–30 (in Czech)

Gałaś A, Paulo A, Gaidzik K, Zavala B, Kalicki T, Churata D, Gałaś S, Mariño J (2018) Geosites and geotouristic attractions proposed for the project Geopark Colca and volcanoes of Andagua, Peru. Geoheritage 10:707–729

Gao W, Li J, Mao X, Li H (2013) Geological and geomorphological value of the monogenetic volcanoes in Wudalianchi National Park, NE China. Geoheritage 5:73–85

Geißler M, Heidenfelder W (2016) Exkursion 1: Geologische Spurensuche im nördlichen Porphyrland um Wurzen: Geopark – Vergangenheit zwischen Vulkanglut and Gletschereis. Schriftenr Dt Gesell Geowiss 88:205–220

Geißler M, Breitkreuz C, Kiersnowski H (2008) Late Paleozoic volcanism in the central part of the southern Permian Basin (NE Germany, W Poland): facies distribution and volcano-topographic hiati. Int J Earth Sci 97:973–989

Geißler M, Hartmann A, Heidenfelder W, Rascher J, Witzke T (2019) Geotope. Einblicke in die Erdgeschichte. Nationaler Geopark Porphyrland, Grimma

Gray M (2013) Geodiversity. Valuing and Conserving Abiotic Nature, 2nd edn. Wiley Blackwell, Chichester

Hoffmann U, Breitkreuz C, Breiter K, Sergeev S, Stanek K, Tichomirova M (2013) Carboniferous-Permian volcanic evolution in Central Europe – U/Pb ages of volcanic rocks in Saxony (Germany) and northern Bohemia. Int J Earth Sci 102:73–99

Hromádko L (n.d.) Drahé kameny a minerály Českého ráje (Precious stones and minerals of Bohemian Paradise). Mineralklub Kozákov 82 (in Czech)

Ihnatowicz A, Koźma J, Wajsprych B (2011) Wałbrzyski Obszar Geoturystyczny – inwentaryzacja geotopów dla potrzeb promocji geoturystyki (Engl. summ. Wałbrzych Geoturist Area – inventory of geotopes for promotion of geotourism). Przegl Geol 59:722–731

Joyce B (2009) Geomorphosites and volcanism. In: Reynard E, Coratza P, Regolini-Bissig G (eds) Geomorphosites. Verlag Dr. Friedrich Pfeil, München, Germany, pp 175–188

Joyce B (2010) Volcano tourism in the new Kanawinka global Geopark of Victoria and SE South Australia. In: Erfurt-Cooper P, Cooper M (eds) Volcano and Geothermal Tourism. Sustainable Geo-resources for Leisure and Recreation. Earthscan, London, pp 302–311

Kasprzak M, Duszyński F, Jancewicz K, Michniewicz A, Różycka M, Migoń P (2016) The Rogowiec landslide complex (central Sudetes, SW Poland) – a case of a collapsed mountain. Geol Quart 60:695–713

Kasprzak M, Jancewicz K, Różycka M, Kotwicka W, Migoń P (2019) Geomorphology and geophysics-based recognition of stages of deep-seated slope deformation (Sudetes, SW Poland). Eng Geol 260:105230

Kołodziejczyk K (2020) The way to the rocks – changes of networks of hiking trails in chosen sandstone landscapes in Poland and the Czech Republic in the period of political transformation. Geoheritage 12:25 (pp 1–30)

Kowalski A, Wojewoda J (2018) Nowo rozpoznane formy osuwiskowe w dolinie Kaczawy na Pogórzu Kaczawskim (Sudety Zachodnie) (Engl. summ. Newly recognized landslide forms in the Kaczawa river valley (Kaczawskie foothills, Western Sudetes). Landf Anal 34:15–27

Liu J, Chen X, Guo W (2012) Volcanic natural resources and volcanic landscape protection: an overview. In: Neméth K (ed) Updates in Volcanology. New Advances in Understanding Volcanic Systems. InTech, Rijeka, pp 181–212

Megerssa L, Rapprich V, Novotný R, Verner K, Erban V, Legesse F, Manaye M (2019) Inventory of key geosites in the Butajira volcanic field: perspective for the first geopark in Ethiopia. Geoheritage 11:1643–1653

Mertlik J, Adamovič J (2016) Bohemian Paradise: sandstone landscape in the foreland of a major fault. In: Pánek T, Hradecký J (eds) Landscapes and Landforms of the Czech Republic. Springer, Switzerland, pp 195–208

Migoń P, Pijet-Migoń E (2017) Geo-interpretation at New Zealand’s geothermal tourist sites – systematic explanation versus storytelling. Geoheritage 9:83–95

Migoń P, Pánek T, Malik I, Hradecký J, Owczarek P, Šilhán K (2010) Complex landslide terrain in the Kamienne Mountains, middle Sudetes, SW Poland. Geomorphology 124:200–214

Migoń P, Jancewicz K, Różycka M, Duszyński F, Kasprzak M (2017) Large-scale slope remodelling by landslides – geomorphic diversity and geological controls, Kamienne Mts, Central Europe. Geomorphology 289:134–151

Niebrzydowska A, Remisz J (2012) Zmiany antropogeniczne wywołane wydobyciem agatów w okolicy Nowego Kościoła (Pogórze Kaczawskie) (Engl. summ. Agate mining in the Nowy Kościół region (Kaczawskie Foothills) as an example of human impact in middle mountains area). In: Łajczak A (ed) Antropopresja w wybranych strefach morfoklimatycznych – zapis zmian w rzeźbie i osadach. Uniwersytet Śląski, Sosnowiec, pp 292–298

Ólafsdóttir R, Dowling R (2013) Geotourism and Geoparks – a tool for geoconservation and rural development in vulnerable environments: a case study from Iceland. Geoheritage 6:71–87

Opluštil S, Schmitz M, Kachlík V, Štamberg S (2016) Re-assessment of lithostratigraphy, biostratigraphy, and volcanic activity of the Late Paleozoic Intra-Sudetic, Krkonoše-Piedmont and Mnichovo Hradiště basins (Czech Republic) based on new U-Pb CA-ID-TIMS ages. Bull Geosci 91(2):399–432

Pijet-Migoń E, Migoń P (2019) Promoting and interpreting geoheritage at the local level – bottom-up approach in the Land of Extinct Volcanoes. Geoheritage 11:1227–1236

Placek A (2011) Rzeźba strukturalna Sudetów w świetle wyników pomiarów wytrzymałości skał i analiz numerycznego modelu wysokości (Rock-controlled morphology of the Sudetes in the light of rock strength measurements and DEM analysis). Rozprawy Naukowe Instytutu Geografii i Rozwoju Regionalnego Uniwersytetu Wrocławskiego 16:1–190 (in Polish)

Rapprich V, Lisec M, Fiferna P, Závada P (2017) Application of modern technologies in popularization of the Czech volcanic geoheritage. Geoheritage 9:413–420

Repstock A, Breitkreuz C, Lapp M, Schulz B (2018) Voluminous and crystal-rich igneous rocks of the Permian Wurzen volcanic system, northern Saxony, Germany: physical volcanology and geochemical characterization. Int J Earth Sci 107:1485–1513

Siedel H (2016) Zur historischen Nutzung nordwestsächsischer Vulkanite als Baustoffe. Schriftenr Dt Gesell Geowiss 88:73–90

Siedel H, Rust M, Goth KA, Heidenfelder W (2019) Rochlitz porphyry tuff (“Rochlitzer Porphyrtuff”): a candidate for “global heritage stone resource” designation from Germany. Episodes 42:81–91

Stárková M, Rapprich V, Breitkreuz C (2011) Variable eruptive styles in an ancient monogenetic volcanic field: examples from the Permian Levín volcanic field (Krkonoše Piedmont Basin, Bohemian Massif). J Geosci 56:163–180

Szepesi J, Harangi S, Ésik Z, Novák TJ, Lukács R, Soós I (2017) Volcanic geoheritage and geotourism perspectives in Hungary: a case of an UNESCO world heritage site, Tokaj wine region historic cultural landscape, Hungary. Geoheritage 9:329–349

Tao KY, Shen JL, Jiang Y, Yu MG (2008) A preliminary discussion on rock-landform of the Yandangshan Mountain. Acta Petrol Sin 24:2647–2656

Tásler R (ed) (1979) Geologie české části vnitrosudetské pánve. Ústřední ústav geologický, Praha (in Czech)

Tefogoum GZ, Nkouathio DG, Dongmo AK, Dedzo MG (2019) Typology of geotouristic assets along the south continental branch of the Cameroon volcanic line: case of the Mount Bambouto’s caldera. Intern J Geoheritage Parks 7:111–128

Traczyk A (2011) Morfologia i geneza przełomowego odcinka doliny Kaczawy między Sędziszową a Nowym Kościołem na Pogórzu Kaczawskim (Morphology and origin of the Kaczawa water gap reach between Sędziszowa and Nowy Kościół in the Kaczawskie Foothills). Przyroda Sudetów 14:167–180 (in Polish)

Ulrych J, Štěpánková J, Novák JK, Pivec E, Prouza V (2002) Volcanic activity in Late Variscan Krkonoše Piedmont Basin: petrological and geochemical constraints. Slovak Geol Mag 8:219–234

Ulrych J, Fediuk F, Lang M, Martinec P (2004) Late Paleozoic volcanic rocks of the intra-Sudetic Basin, Bohemian Massif: petrological and geochemical characteristics. Geochemistry 64:127–153

Ulrych J, Pešek J, Štěpánková-Svobodova J, Bosák P, Lloyd FE, von Seckendorff V, Lang M, Novák JK (2006) Permo-Carboniferous volcanism in late Variscan continental basins of the Bohemian Massif (Czech Republic): geochemical characteristic. Geochemistry 66:37–56

Vítek J (2016) Adršpach-Teplice rocks and Broumov cliffs – large sandstone rock cities in the Central Europe. In: Pánek T, Hradecký J (eds) Landscapes and Landforms of the Czech Republic. Springer, Switzerland, pp 209–220

Woo KS, Sohn YK, Yoon SH, Ahn US, Spate A (2013) Jeju Island Geopark – a Volcanic Wonder of Korea. Springer, Berlin – Heidelberg

Wood C (2009) World Heritage volcanoes: thematic study. IUCN, Gland

Acknowledgements

We are very grateful to two journal reviewers for their insightful comments and suggestions for improvement, as well as linguistic correction.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Migoń, P., Pijet-Migoń, E. Late Palaeozoic Volcanism in Central Europe—Geoheritage Significance and Use in Geotourism. Geoheritage 12, 43 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12371-020-00464-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12371-020-00464-5