Abstract

Pennisetum sinese Roxb (P. sinese) is an efficient and economic energy crop for its high productivity, and has been well studied in its application in phytoremediation and fodder production. However, little is known about how P. sinese plantation and fermented manures of P. sinese-feed livestock affect the composition of soil bacterial and fungal communities. In this study, 16S rRNA/ITS1 gene-based Illumina Miseq sequencing was employed to compare the bacterial and fungal community structure among soils that had been subjected to uncultivated control (CK), 2-year P. sinese plantation (P), and P. sinese plantation combined with the use of organic manures (P-OM) in a “P. sinese—breeding industry” ecological agriculture farm. The results found microbial communities were altered by P. sinese plantation and fertilization. The P. sinese plantation resulted in increased Actinobacteria and Planctomycetes abundance. Comparatively, significant increased abundance of Chloroflexi, Firmicutes, Nitrospirae, and Euryarchaeota, and genes related with nitrogen and carbon metabolic pathways based on PICRUSt prediction was observed in P-OM soil. Fungal compositions suggested a markedly increased abundance of Ascomycota in P soil. Potential organic matter decomposers Candida, Thermoascus, and Aspergillus were enriched in P soil, indicating the enhanced role of fungi in litter decomposition. Redundancy analysis suggested that soil properties (NH4+-N, total nitrogen, organic matter content, and soil water content) significantly correlated with the changes of microbial compositions (P < 0.05). These results highlight the divergence of microbial communities occurs during P. sinese-based plantation, implying functional diversification of soil ecosystem in P. sinese fields.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

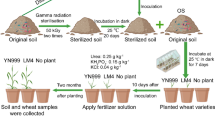

The development of ecological agriculture has been regarded as an important mean to realize the coordinated development of the environment and economy, which is particularly the case in China (Shi and Gill 2005). Among the ecological agriculture development models, the model of “P. sinese—breeding industry” is one of common practices which has been established in many farms and villages (Chen et al. 2012; Wei 2005). P. sinese, widely known as giant bamboo grass or king grass, is a type of fast-growing perennial and monocot C4 plant with highly developed root systems, high yield of stems and leaves, and high level of protein and sugar contents (Lu et al. 2014). P. sinese with strong adaptability is widely planted and extensively distributed in tropical and subtropical regions. These capacities have carved a niche for itself in phytoremediation (Chen et al. 2017), soil reclamation (Senlin et al. 2017), and fodder source (Yongfen 1999). In these farms, fresh stem leaves of P. sinese are fed to livestock, and then the fermented livestock manures as organic matter are applied into arable fields to maximize the crop yields (He et al. 2012) (as illustrated in Fig. 1 and Additional file 1: Fig. S1). Previous studies revealed that P. sinese plantation could be beneficial for enhancing the soil fertility (Xu et al. 2015; Lin et al. 2014). Fundamentally, it is microorganisms inhabiting soil ecosystem play crucial roles in maintaining soil ecological functions, including maintaining ecosystem health and nutrients biogeochemical cycling (Rick and Thomas 2001). However, little is known about how P. sinese plantation and organic manure of P. sinese-feed livestock affect the composition of microbial communities and their roles in maintaining soil productivity.

Microbial composition and diversity are manipulated by environment conditions (Singh et al. 2009), which is reflected in the high sensitivity of microorganisms to anthropogenic or natural disturbance (Yin et al. 2010). A number of studies have shown that shifts of bacterial and fungal community structure are related to the alteration of soil nutrient contents (van der Wal et al. 2006; Gravuer and Eskelinen 2017) and soil pH (Shen et al. 2013). Vegetation type is another main factor in shaping microbial communities (Nielsen et al. 2010). This is quite reasonable that vegetation could alter soil physicochemical and biotic parameters by secreting root exudate (such as amino acids, sugars, polysaccharides or proteins) (Badri and Vivanco 2009), accumulating root residues (Shahbaz et al. 2017), and preferential assimilation of nutrient substrates (Bai et al. 2017), and thus act as a selective force to drive the diversification of microbial communities. It has been reported that P. sinese can stimulate the enzyme activities of soil microbial populations (Cui et al. 2016), and enhance microbial community functional diversity (Lin et al. 2014). Moreover, P. sinese showed a great uptake capacity of nitrogen and phosphorus from wetland (Xu et al. 2015). However, it remains to be seen whether the soil bacterial and fungal communities response to plantation of P. sinese.

Increasing lines of evidences have suggested that livestock manures as organic fertilizers could exert a remarkable influence on altering the microbial communities (Zhong et al. 2010; Dumontet et al. 2017). For example, addition of livestock manures increased microbial diversity (Sun et al. 2015), which could even be detected within a short period of fertilization (Lazcano et al. 2013). Hence, an attempt to determine the shifts in bacterial and fungal patterns caused by the fermented manures from P. sinese-feed livestock have also been explored in the present study.

We hypothesized that the soil microbial communities response strongly to the plantation of P. sinese and application of livestock manures, and show a significant correlation of soil microbial community compositions with soil physicochemical parameters. Here, soils with a P. sinese cultivation and fertilization history of 2 year in an ecological farm were selected to investigate the community diversification of bacteria and fungi using 16S rRNA/ITS1 gene-based Illumina MiSeq sequencing.

Materials and methods

Site description and soil sampling

The soils were collected from the experimental field at Huangjialou Village ecological farm where a recycling system was established in 2016 (30° 29′ N, 106° 40′ E). The village is located in Nanchong City of Sichuan Province in southwest China. Huangjialou village is also one of the key villages which are listed in poverty alleviation project in China. This region has a typical mid-subtropical humid monsoon climate with a mean annual temperature of 17.0 °C. The soil sampling sites were converted from abandoned land to P. sinese planting field for 2 years. The harvested P. sinese is used for feeding animals (chicken, goose, rabbit, cattle, and sheep). The manures from animals are fermented, and then spread as organic fertilizers for P. sinese and other crops in each season, at ~ 200.0 kg ha−1 (fresh weight). Three sample plots received different treatments consisting of (1) an uncultivated abandoned land control (CK); (2) 2-year P. sinese planting (P); (3) a combination of 2-year P. sinese planting and organic manure fertilization (P-OM). Each plot sampling was conducted in triplicate.

Soil sampling was performed using a hand trowel at a depth of 0–10 cm. Plant residues and other materials, such as visible macrofauna and stones, were removed before the sampling. The soils were placed in sterile plastic bags, sealed, and transported to the laboratory within 2 h. Soils were stored at − 20 °C for physicochemical and molecular analysis.

Sample physicochemical analysis

The soil pH was measured by a pH meter (Mettler-Toledo Instruments Co. Ltd., Shanghai, China) using a soil-to-water ratio of 1:2.5. The soil organic matter (SOM) content was determined using a total carbon analyzer (TOC-V CPH, Shimadzu, Japan). Total nitrogen (TN) was determined using the Kjeldahl digestion method (Bremner 1965). The soil water content (SWC) was measured by drying the fresh sample at 105 °C for 6 h. 5 g of fresh soil was homogenized with 20 ml of 2 M KCl by shaking at 150 r.p.m for 60 min, and then passed through a Whatman® Grade 1 qualitative filter paper (circles, diam. 110 mm) for the determination of NH4+-N, NO2−-N, and NO3−-N using a Skalar SAN Plus segmented flow analyser (Skalar, Breda, the Netherlands). All the soil parameters were calculated based on oven-dried soil weight. All samples were analyzed in three replicates.

Soil DNA extraction and real-time quantitative PCR

Total DNA extraction from the soils was performed using a FastDNA spin kit for soil (Qbiogene, Irvine, CA). 0.5 g soil was used directly for DNA extraction. The quality and quantity of extracted DNA were determined using a NanoDrop spectrophotometer (NanoDrop Technologies, Wilmington, Germany). The DNA was stored at − 20 °C until use.

Illumina Miseq sequencing of 16S rRNA and ITS1 gene amplicons

Illumina Miseq sequencing was employed to investigate the shifts of bacterial and fungi communities in CK, P, and P-OM soils. The primer pairs 515/907 and ITS 5F/1R were used for the amplification of bacterial 16S rRNA and fungal ITS1 genes, respectively. The PCR primers and conditions are listed Additional file 1: Table S1. All PCR amplifications were conducted in triplicate for each treatment, and then visualized on 1.0% agarose gels with GoldView™. The concentration of the purified PCR amplicons was determined, and these amplicons were used for the Miseq sequencing. The Miseq sequencing data were analysed using the QIIME 2 software package (Bokulich et al. 2017). The detailed analysis for sequencing was performed as described previously (Wang et al. 2018).

Statistical analysis

The chemical properties data of the soils were compared though multiple sample comparisons using one-way ANOVA analysis to check for quantitative variances among different soil samples. SPSS version 20.0 was used for statistical analysis (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Correlations between soil physicochemical properties and bacterial, fungal community compositions were carried out using CANOCO 4.5 software package (Biometris, Wageningen, The Netherlands). Bacterial and fungal community comparisons at phylum and genus level were performed using Metastats (White et al. 2009). Bacterial functional gene prediction was determined using Phylogenetic Investigation of Communities by Reconstruction of Unobserved States (PICRUSt) (Langille et al. 2013).

Result

Soil properties

The P. sinese plantation and organic manures did not result in a significant change in pH values from 8.43 ± 0.15 in CK control soil to 8.22 ± 0.04, and 8.39 ± 0.15 in P and P-OM treatments, respectively (Table 1). The contents of SOM and NH4+-N were statistically higher in the P-OM soil than those in the CK soil (P < 0.05), whereas the SOM and NH4+-N content showed a decreasing trend in P soil. SOM and NH4+-N contents were elevated by 49.0% and 40.3%, respectively, in the P-OM soil compared with the CK soil. Similarly, the P-OM soil showed increase by 2.94-fold for TN. Decreased content of soil SOM, NO3−-N, NH4+-N by 31.9%, 16.9%, and 41.3% was observed in P soil compared to CK soil. The soil water content ranged from 12.62 to 24.25% with the lowest content in P soil.

Richness and diversity of microbial communities

316,485 and 298,832 high-quality sequences for bacteria and fungi were obtained in total (Table 1). The OTUs number of bacteria showed an obvious increase from 2009 ± 105 in CK soil to 2276 ± 3 in P-OM oil, whereas a significant decrease was observed in P soil with 1950 ± 3 OTUs. The fungal OTUs number also decreased in P soil compared to CK soil. The fungal OTUs number in P-OM and CK soils showed no significant differences (P > 0.05). The richness Chao1 and ACE values obviously showed that the bacterial richness in P soil was higher than those in CK soil, while the opposite trend was observed for P-OM soil (Fig. 2). It appeared that the fungal Shannon and Simpson values decreased significantly in P and P-OM soils compared to CK soil (P < 0.05). It is noteworthy that soil TN content was found positively related with all four diversity indexes of bacteria communities (P < 0.05) (Table 2). A positive correlation also existed between SOM, SWC, NH4+-N and the bacterial ACE, Chao1 values. Besides, The Simpson and Shannon index of fungal communities were positively correlated with soil NO3−-N content.

Bacterial community composition

The dominant phyla across the soil samples were Proteobacteria, Chloroflexi, Acidobacteria, Actinobacteria, Nitrospirae, Planctomycetes, Thaumarchaeota, and Bacteroidetes, accounting for more than 89.42% of the bacterial sequences in the three soil samples (Fig. 3a). Proteobacteria represented the most abundance phylum with 29.01%, 29.84%, 27.71% of the total sequences in CK, P, and P-OM soil, respectively. The relative abundance of Alpha-, Beta-, Gamma-, and Delta-proteobacteria varied among different soils (Fig. 3a). P. sinese plantation led to 21.28%, 15.60% increase in the relative abundance of Actinobacteria and Planctomycetes in P soil compared to CK soil. The relative abundance of Chloroflexi, Firmicutes, Nitrospirae, and Euryarchaeota were significantly higher in P-OM soil than those found in CK soil (P < 0.05). Metastats analysis of the soil bacterial community found 9 and 25 phyla in P and P-OM soils showing significant differences compared to that of CK soil, respectively (P < 0.05) (Table 3).

The striking microbial community differences among treatments can be observed in the heatmap of the top 50 genera (Fig. 4a). The P. sinese plantation resulted in significant increased Acinetobacter, Rhizobium, Streptomyces, Ramlibacter, Arthrobacter, and Mycobacterium by 36.1-, 3.24-, 2.81-, 2.26-, 2.05-, and 1.91-fold in P soil compared to CK soil (Additional file 1: Fig. S2). Sequences belonging to Anaerolinea, Geobacter, Thauera, and Bacillus were highly enriched in the P-OM soil representing 19.4-, 9.60-, 4.10-, and 3.36-fold increase compared with the P soil, respectively.

Fungal community composition

The predominant fungal phyla (Ascomycota, Zygomycota, Basidiomycota, Chytridiomycota) represented > 98.09% of the total sequences in the three treatments, with Ascomycota the most dominant phyla (57.45–89.89%) (Fig. 3b). Metastats analysis of the soil fungal community found 8 and 9 phyla in P and P-OM soils showing significant differences compared to that of CK soil, respectively (Table 3). The relative abundance of Ascomycota increased from 57.45 ± 11.76% in the CK soil to 76.02 ± 12.50% and 89.89 ± 2.04% in the P and P-OM soil respectively. A opposite change trend was observed in the phyla of Zygomycota, which were reduced by 3.05-and 5.94-fold in the P and P-OM soil. Basidiomycota also showed a significant decreased after P. sinese plantation and fertilization.

In terms of genus level, there were significant dissimilarities in the relative abundances of the dominant fungal genera in the three treatments (Fig. 4b). Specifically, the relative abundance of Mortierella (3.84%) in P soil was markedly lower than in CK soil (18.7%), and a further decrease in Mortierella relative abundance was found in P-OM soil (0.61%). The dominant genus shifted from Mortierella, Volvopluteus, and Chaetomium in CK soil to Candida, Thermoascus, Hyphopichia, Rhizomucor, Aspergillus in P soil. Candida (12.3%) was the uppermost genus in P-OM soil, followed by Acremonium (9.38%), Thermoascus (5.86%). Besides, sequences affiliated with Gibellulopsis, Sarocladium, Acremonium increased by 119-, 53.8-, and 6.28-fold in P-OM soil.

PICRUSt analysis of soil bacterial metabolism function

In order to compare the functional potentials of the soil samples, functional metabolisms were predicted based on the bacterial OTUs using PICRUSt (Langille et al. 2013). Genes related with nitrogen and carbon metabolic pathways were significantly more abundant in P-OM soil than in CK and P soil (Table 4). In addition, genes involved in xenobiotic biodegradation metabolism, metabolism of terpenoids and polyketides, and amino acid metabolism in P soils had the highest abundance of the three treatments (Additional file 1: Fig. S3).

Multivariate correlation analysis between bacterial and fungal communities and environmental variables

RDA was performed based on genus-level data to determine the correlation between bacterial, fungal communities and soil physicochemical properties (Fig. 5). Figure 5a illustrated a clear separation of bacterial communities in different treatments on the first ordination axis of the plot by ANOSIM analysis (P < 0.01), which accounted for 91.6%. NH4+-N (P = 0.008), TN (P = 0.002), and SOM (P = 0.002) content were the significant determinant factors for explaining the variation in bacterial community composition (Table 5). SOM explained up to 86.0% of the total bacterial variation. For fungi, the first two canonical axes for community composition explained 63.9% and 15.4% of the variations, respectively. TN content was statistically the most significant factor determining the fungal community composition, which explained 44% of the variation. Another 35% of the variation was also significantly related with SWC and NH4+-N (P < 0.05).

Discussion

The “P. sinese—breeding industry” ecological agriculture farm served as a model system to investigate soil microbial communities in response to 2-year P. sinese plantation and organic fertilization. Our results exhibited the distinct soil bacterial and fungal community patterns after P. sinese plantation and organic fertilization, which was accompanied by the changes of soil chemical properties.

The diversity of bacterial communities was much higher than those of fungal communities, which agreed well with the previous finding (Tian et al. 2017). The positive correlation between the bacterial diversity and soil TN content (Table 2), supported by the result from Shen et al. (2013), whereas NO3−-N content was the most dominant variable to govern the fungal diversity, which could be explained by the high susceptibility of fungi to NO3− availability (Lilleskov et al. 2002). Here, the bacterial diversity indexes did not increase after P. sinese plantation. However, opposite results were reported for Eucalyptus plantation (Chen et al. 2013) and larch plantations (Zhang et al. 2017), indicating different plant species might have different effects on soil bacterial communities. In contrast, increased diversity indexes were observed in P-OM soil, which could be caused by the application of organic manure (Zhong et al. 2010, Zhang et al. 2012).

The bacterial communities was dominated by Proteobacteria, Chloroflexi, Acidobacteria, Actinobacteria which were also found in other soils (Stott et al. 2008; Khodadad et al. 2011). Significant increase of Actinobacteria and Planctomycetes abundance after P. sinese plantation was observed. Actinobacteria have the potential for promoting plant growth (Hamdali et al. 2008), and is known to play an important role in mineralizing N and decomposing organic material (such as chitin and cellulose) (Li et al. 2010). The pronounced increase of Actinobacteria after P. sinese plantation might be fueled by its highly developed underground roots system of P. sinese. The increased abundance of genera Streptomyces, Arthrobacter, and Mycobacterium belonging to Actinobacteria was also observed in the pepper plantation soil (Hahm et al. 2017). It is noteworthy that Streptomyces has been proposed as beneficial microbes for their capacity of plant diseases suppression (Chen et al. 2018), illustrating that P. sinese plantation could improve soil resistance for soil-borne diseases. Besides, 36.1-fold increase of Acinetobacter was highly enriched in P soil. Some species within Acinetobacter have been reported for their root colonization properties and broad-spectrum plant growth-promoting metabolic activities (Gulati et al. 2009). The high abundance of Acinetobacter in P soil might be caused by the mutualism between P. sinese and Acinetobacter (Goldstein et al. 1999).

Our results showed that the bacteria phyla Chloroflexi, Firmicutes, Nitrospirae, and Euryarchaeota significantly proliferated in P-OM soil. However, different results were reported for organic manure-involved agricultural soils where copiotrophic Proteobacteria dominated (Ge et al. 2008; Sun et al. 2015). The growth of anaerobic Anaerolinea mostly contributed the increased phylum Chloroflexi. This observation was consistent with previous study showing that organic fertilizer significantly stimulated the growth of Anaerolinea (Wu et al. 2017). It was also found that Anaerolinea has the metabolic potential for respiring diverse carbon compounds (Hug et al. 2013). Higher abundance of Anaerolinea in the P-OM soil compared to CK and P soil might be a result of high organic matter substrates (Table 1). High abundance of Firmicutes in P-OM soil was consistent with previous studies showing that Firmicutes is more abundant in soils amended with organic manures (Xun et al. 2016; Faissal et al. 2017). As previously reported (Feng et al. 2015), Bacillus belonging to Firmicutes responds most distinctly to organic manure fertilization. Yumoto et al. (2004) reported that a variety of short-chain fatty acids resulting from organic manure fermentation are excellent substrates for Bacillus. Other study also confirmed that the composted manure has the promoting impact on the growth of indigenous Bacillus in soils (Chu et al. 2007). An increased abundance of Bacillus in P-OM soil was also observed in this study. Moreover, members of Bacillus have the ability to suppress soil-borne pathogens (Weller et al. 2002) and increase soil fertility by increasing nutrient availability (Chen 2006), suggesting the potential benefits of P. sinese-feed organic manures application in the ecological agriculture farm. Nitrospirae is known to participate in nitrification (Lücker et al. 2010), which was coupled well with high NH4+ substrate and increased relative abundance of genes related with nitrogen metabolic pathway in the P-OM soil (Table 1 and Additional file 1: Fig. S4). It was found that fertilizers could enhance the abundance of carbon, nitrogen cycling genes (Nemergut et al. 2008; Su et al. 2014), which thus stimulating soil nutrient turnorver. In parallel, the content of NH4+-N and TN were statistically higher in the P-OM soil than those in the CK soil, indicating that increases in N and C availability in the P-OM soil may spur the alteration of the carbon and nitrogen-involved bacteria activities (Mickan et al. 2018).

Increased Euryarchaeota in P-OM soil were mostly associated with methanogens, such as Methanoregula, Methanospirillum, and Methanosarcina (Additional file 1: Fig. S5), which are all recognized as the key contributor for methane emission in soils (Narihiro et al. 2011; Iino et al. 2010, Gattinger et al. 2007). This observation was in line with those from other studies, showing enhanced abundance of methanogens due to organic manure application (Das and Adhya 2014; Gattinger et al. 2007). Higher abundance of genes related with methane metabolic pathways in P-OM soil compared to CK and P soil also supported this result (Additional file 1: Fig. S4). In addition, Geobacter and Thauera belonging to Proteobacteria were markedly enriched in P-OM soil, which was in agreement with previous studies in organic fertilized soils (Pershina et al. 2015; Luo et al. 2017). Intriguingly, Geobacter is famous for its crucial role in metal reduction and precipitation, and carbon cycling (Methe et al. 2003). For example, Geobacter metallireducens is capable of coupling the complete oxidation of organic compounds to the reduction of Fe(III), Mn(IV) and other metals (Lovley et al. 1993). According to the above results, the changes in bacterial community structure provide strong hints regarding the divergence of soil bacterial ecological function after P. sinese plantation and manures fertilization.

The fungal communities observed here showed dramatic variations in different soil treatments. The pronounced increased of Ascomycota in P (76.02%) and P-OM (89.89%) soil was observed. Ascomycota are particularly common in soils as the main fungal decomposer (Tian et al. 2017), and its abundance is also largely tied to plant species (Curlevski et al. 2010). Ascomycota was enriched after P. sinese plantation (Fig. 4) and Eucalyptus plantations (Rachid et al. 2015), whereas Basidiomycota rather than Ascomycota dominated in sub-boreal forest soil (Phillips et al. 2014). Members of Ascomycota are associated with litter decomposition (Ma et al. 2013) and lignocellulose degradation (Lopez et al. 2007). The increased abundance of Ascomycota in P soil might be caused by P. sinese residue which contains organic matter like lignocellulose, holocellulose, or lignin (Tian et al. 2017). Moreover, increased Ascomycota mainly contained the genus of Candida, Thermoascus, and Aspergillus which have been found to have positive effects on the decomposition of plant litter (Squina et al. 2009; Ghaly et al. 2011). For example, Candida showed a positive effect on the litter mass loss (Cragg and Bardgett 2001). Species within Aspergillus genus contains the genes for hydrolysis of xylan which is abundant in plant polysaccharide (Squina et al. 2009). Comparatively, dramatically increase of Gibellulopsis, Sarocladium, and Acremonium abundance in P-OM soil compared to that in P soil could be impacted by the manure fertilization, which was also observed in organic amended soils (Swer and Dkhar 2014; Gleń-Karolczyk et al. 2018). Among them, Acremonium can be actively involved in the decomposition of leaf litter by producing lignocellulolytic enzymes (Hao et al. 2006). Thus, the shift of fungal communities implied that the fungal groups related with decomposition could lead to the alteration of soil carbon turnover rate, which warrants further study.

NH4+-N, TN, and SOM content were the most significant factors determining the bacterial community composition in the three treatments. TN content was the most predominant factor in sharping the fungal community structure. This observation is in accordance with many other studies reporting that fungal communities are associated with changes in soil nitrogen availability (Frey et al. 2004). In the current study, the relative abundance of Ascomycota displayed a positive correlative with TN content (r = 0.92, P = 0.001) as reported in previous study (Weber et al. 2013). Besides, SWC and NH4+-N also contributed to the variation in fungi community composition as descried in previous studies (Weber et al. 2013; Drenovsky et al. 2004). Taken together, our data highlight the deterministic role of soil properties in shaping microbial communities.

In summary, our results demonstrate that the P. sinese plantation and organic manures in an ecological agriculture farm significantly altered the bacterial and fungi communities structure. Bacterial metabolism function prediction results showed the relative abundance of genes associated different metabolic pathways, such as nitrogen and carbon metabolism, varied among different soils. NH4+-N, TN, and SOM content are important factors for structuring the bacterial communities, whereas TN, NH4+-N, and SWC are steering factors to determine the fungi communities. Overall, these findings exhibit a delicate relation in agriculture practice, soil chemical properties, and microbial communities, highlighting the importance of revealing the compositional and functional diversification of microorganism in agriculture ecosystem.

Availability of data and materials

All datasets from which the conclusions of the manuscript rely were presented in the main paper. The nucleotide sequences were deposited at the GenBank with accession numbers. The nucleotide sequences were deposited at the GenBank with Accession numbers SRR8052532–SRR8052540 and SRR8052578–SRR8052586 for the bacteria and fungi in this study, respectively.

References

Badri DV, Vivanco JM (2009) Regulation and function of root exudates. Plant Cell Environ 32:666–681

Bai J, Jia J, Huang C, Wang Q, Wang W, Zhang G, Cui B, Liu X (2017) Selective uptake of nitrogen by Suaeda salsa under drought and salt stresses and nitrogen fertilization using 15N. Ecol Eng 102:542–545

Bokulich, N, Zhang, Y, Dillon, M, Rideout, JR, Bolyen, E, Li, H, Albert, P and Caporaso, JG (2017) q2-longitudinal: a QIIME 2 plugin for longitudinal and paired-sample analyses of microbiome data. bioRxiv: 223974

Bremner J (1965) Total nitrogen. Methods of soil analysis. Part 2. Chemical and microbiological properties, pp 1149–1178

Chen J-H (2006) The combined use of chemical and organic fertilizers and/or biofertilizer for crop growth and soil fertility. In: International workshop on sustained management of the soil-rhizosphere system for efficient crop production and fertilizer use, Citeseer, pp 20

Chen Z-D, Huang Q-L, Huang X-S, Feng D-Q, Zhong Z-M (2012) Breeding and cultivation technology of Pennisetum. Acta Ecol Anim Domastici 1:011

Chen F, Zheng H, Zhang K, Ouyang Z, Lan J, Li H, Shi Q (2013) Changes in soil microbial community structure and metabolic activity following conversion from native Pinus massoniana plantations to exotic Eucalyptus plantations. For Ecol Manage 291:65–72

Chen Y, Hu L, Liu X, Deng Y, Liu M, Xu B, Wang M, Wang G (2017) Influences of king grass (Pennisetum sinese Roxb)-enhanced approaches for phytoextraction and microbial communities in multi-metal contaminated soil. Geoderma 307:253–266

Chen Y, Zhou D, Qi D, Gao Z, Xie J, Luo Y (2018) Growth promotion and disease suppression ability of a Streptomyces sp. CB-75 from banana rhizosphere soil. Front Microbiol 8:2704

Chu H, Lin X, Fujii T, Morimoto S, Yagi K, Hu J, Zhang J (2007) Soil microbial biomass, dehydrogenase activity, bacterial community structure in response to long-term fertilizer management. Soil Biol Biochem 39:2971–2976

Cragg RG, Bardgett RD (2001) How changes in soil faunal diversity and composition within a trophic group influence decomposition processes. Soil Biol Biochem 33:2073–2081

Cui H, Fan Y, Yang J, Xu L, Zhou J, Zhu Z (2016) In situ phytoextraction of copper and cadmium and its biological impacts in acidic soil. Chemosphere 161:233–241

Curlevski NJ, Xu Z, Anderson IC, Cairney JW (2010) Converting Australian tropical rainforest to native Araucariaceae plantations alters soil fungal communities. Soil Biol Biochem 42:14–20

Das S, Adhya TK (2014) Effect of combine application of organic manure and inorganic fertilizer on methane and nitrous oxide emissions from a tropical flooded soil planted to rice. Geoderma 213:185–192

Drenovsky R, Vo D, Graham K, Scow K (2004) Soil water content and organic carbon availability are major determinants of soil microbial community composition. Microb Ecol 48:424–430

Dumontet S, Cavoski I, Ricciuti P, Mondelli D, Jarrar M, Pasquale V, Crecchio C (2017) Metabolic and genetic patterns of soil microbial communities in response to different amendments under organic farming system. Geoderma 296:79–85

Faissal A, Ouazzani N, Parrado J, Dary M, Manyani H, Morgado B, Barragan M, Mandi L (2017) Impact of fertilization by natural manure on the microbial quality of soil: molecular approach. Saudi J Biol Sci 24:1437–1443

Feng Y, Chen R, Hu J, Zhao F, Wang J, Chu H, Zhang J, Dolfing J, Lin X (2015) Bacillus asahii comes to the fore in organic manure fertilized alkaline soils. Soil Biol Biochem 81:186–194

Frey SD, Knorr M, Parrent JL, Simpson RT (2004) Chronic nitrogen enrichment affects the structure and function of the soil microbial community in temperate hardwood and pine forests. For Ecol Manage 196:159–171

Gattinger A, Höfle MG, Schloter M, Embacher A, Böhme F, Munch JC, Labrenz M (2007) Traditional cattle manure application determines abundance, diversity and activity of methanogenic Archaea in arable European soil. Environ Microbiol 9:612–624

Ge Y, Zhang J-b, Zhang L-m, Yang M, He J-z (2008) Long-term fertilization regimes affect bacterial community structure and diversity of an agricultural soil in northern China. J Soils Sediments 8:43–50

Ghaly A, Zhang B, Dave D (2011) Biodegradation of phenolic compounds in creosote treated wood waste by a composting microbial culture augmented with the fungus Thermoascus aurantiacus. Am J Biochem Biotechnol 7:90–103

Gleń-Karolczyk K, Boligłowa E, Antonkiewicz J (2018) Organic fertilization shapes the biodiversity of fungal communities associated with potato dry rot. Appl Soil Ecol 129:43–51

Goldstein AH, Braverman K, Osorio N (1999) Evidence for mutualism between a plant growing in a phosphate-limited desert environment and a mineral phosphate solubilizing (MPS) rhizobacterium. FEMS Microbiol Ecol 30:295–300

Gravuer K, Eskelinen A (2017) Nutrient and rainfall additions shift phylogenetically estimated traits of soil microbial communities. Front Microbiol 8:1271

Gulati A, Vyas P, Rahi P, Kasana RC (2009) Plant growth-promoting and rhizosphere-competent Acinetobacter rhizosphaerae strain BIHB 723 from the cold deserts of the Himalayas. Curr Microbiol 58:371–377

Hahm M-S, Son J-S, Kim B-S, Ghim S-Y (2017) Comparative study of rhizobacterial communities in pepper greenhouses and examination of the effects of salt accumulation under different cropping systems. Arch Microbiol 199:303–315

Hamdali H, Hafidi M, Virolle MJ, Ouhdouch Y (2008) Growth promotion and protection against damping-off of wheat by two rock phosphate solubilizing actinomycetes in a P-deficient soil under greenhouse conditions. Appl Soil Ecol 40:510–517

Hao JJ, Tian XJ, Song FQ, He XB, Zhang ZJ, Zhang P (2006) Involvement of lignocellulolytic enzymes in the decomposition of leaf litter in a subtropical forest. J Eukaryot Microbiol 53:193–198

He W, Wang L, Zhang J (2012) Effects of application amounts of biogas slurry on yield of Pennisetum sinese and soil fertility. Prataculture Anim Husb 2:005

Hug LA, Castelle CJ, Wrighton KC, Thomas BC, Sharon I, Frischkorn KR, Williams KH, Tringe SG, Banfield JF (2013) Community genomic analyses constrain the distribution of metabolic traits across the Chloroflexi phylum and indicate roles in sediment carbon cycling. Microbiome 1:22

Iino T, Mori K, Suzuki K-i (2010) Methanospirillum lacunae sp. nov., a methane-producing archaeon isolated from a puddly soil, and emended descriptions of the genus Methanospirillum and Methanospirillum hungatei. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 60:2563–2566

Khodadad CL, Zimmerman AR, Green SJ, Uthandi S, Foster JS (2011) Taxa-specific changes in soil microbial community composition induced by pyrogenic carbon amendments. Soil Biol Biochem 43:385–392

Langille MG, Zaneveld J, Caporaso JG, McDonald D, Knights D, Reyes JA, Clemente JC, Burkepile DE, Thurber RLV, Knight R (2013) Predictive functional profiling of microbial communities using 16S rRNA marker gene sequences. Nat Biotechnol 31:814–821

Lazcano C, Gómez-Brandón M, Revilla P, Domínguez J (2013) Short-term effects of organic and inorganic fertilizers on soil microbial community structure and function. Biol Fertil Soils 49:723–733

Li X, She Y, Sun B, Song H, Zhu Y, Lv Y, Song H (2010) Purification and characterization of a cellulase-free, thermostable xylanase from Streptomyces rameus L2001 and its biobleaching effect on wheat straw pulp. Biochem Eng J 52:71–78

Lilleskov EA, Fahey TJ, Horton TR, Lovett GM (2002) Belowground ectomycorrhizal fungal community change over a nitrogen deposition gradient in Alaska. Ecology 83:104–115

Lin X, Lin Z, Lin D, Lin H, Luo H, Hu Y, Lin C, Zhu C (2014) Effects of planting Pennisetum sp. (Giant Juncao) on soil microbial functional diversity and fertility in the barren hillside. Acta Ecol Sin 34:4304–4312

Lopez MJ, del Carmen Vargas-García M, Suárez-Estrella F, Nichols NN, Dien BS, Moreno J (2007) Lignocellulose-degrading enzymes produced by the ascomycete Coniochaeta ligniaria and related species: application for a lignocellulosic substrate treatment. Enzyme Microb Technol 40:794–800

Lovley DR, Giovannoni SJ, White DC, Champine JE, Phillips EJP, Gorby YA, Goodwin S (1993) Geobacter metallireducens gen. nov. sp. nov., a microorganism capable of coupling the complete oxidation of organic compounds to the reduction of iron and other metals. Arch Microbiol 159:336–344

Lu Q-L, Tang L-R, Wang S, Huang B, Chen Y-D, Chen X-R (2014) An investigation on the characteristics of cellulose nanocrystals from Pennisetum sinese. Biomass Bioenergy 70:267–272

Lücker S, Wagner M, Maixner F, Pelletier E, Koch H, Vacherie B, Rattei T, Damsté JSS, Spieck E, Le Paslier D (2010) A Nitrospira metagenome illuminates the physiology and evolution of globally important nitrite-oxidizing bacteria. Proc Natl Acad Sci 107:13479–13484

Luo G, Ling N, Nannipieri P, Chen H, Raza W, Wang M, Guo S, Shen Q (2017) Long-term fertilisation regimes affect the composition of the alkaline phosphomonoesterase encoding microbial community of a vertisol and its derivative soil fractions. Biol Fertil Soils 53:375–388

Ma A, Zhuang X, Wu J, Cui M, Lv D, Liu C, Zhuang G (2013) Ascomycota members dominate fungal communities during straw residue decomposition in arable soil. PLoS ONE 8:e66146

Methe B, Nelson KE, Eisen J, Paulsen IT, Nelson W, Heidelberg J, Wu D, Wu M, Ward N, Beanan M (2003) Genome of Geobacter sulfurreducens: metal reduction in subsurface environments. Science 302:1967–1969

Mickan B, Abbott L, Fan J, Hart M, Siddique K, Solaiman Z, Jenkins S (2018) Application of compost and clay under water-stressed conditions influences functional diversity of rhizosphere bacteria. Biol Fertil Soils 54:55–70

Narihiro T, Hori T, Nagata O, Hoshino T, Yumoto I, Kamagata Y (2011) The impact of aridification and vegetation type on changes in the community structure of methane-cycling microorganisms in Japanese wetland soils. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem 75:1727–1734

Nemergut DR, Townsend AR, Sattin SR, Freeman KR, Fierer N, Neff JC, Bowman WD, Schadt CW, Weintraub MN, Schmidt SK (2008) The effects of chronic nitrogen fertilization on alpine tundra soil microbial communities: implications for carbon and nitrogen cycling. Environ Microbiol 10:3093–3105

Nielsen UN, Osler GH, Campbell CD, Burslem DF, van der Wal R (2010) The influence of vegetation type, soil properties and precipitation on the composition of soil mite and microbial communities at the landscape scale. J Biogeogr 37:1317–1328

Pershina E, Valkonen J, Kurki P, Ivanova E, Chirak E, Korvigo I, Provorov N, Andronov E (2015) Comparative analysis of prokaryotic communities associated with organic and conventional farming systems. PLoS ONE 10:e0145072

Phillips LA, Ward V, Jones MD (2014) Ectomycorrhizal fungi contribute to soil organic matter cycling in sub-boreal forests. ISME J 8:699

Rachid CTCC, Balieiro FC, Fonseca ES, Peixoto RS, Chaer GM, Tiedje JM, Rosado AS (2015) Intercropped silviculture systems, a key to achieving soil fungal community management in eucalyptus plantations. PLoS ONE 10:e0118515

Rick WY, Thomas SM (2001) Microbial nitrogen cycles: physiology, genomics and applications. Curr Opin Microbiol 4:307–312

Senlin Z, Zhang A, Shanyuan W, Xu C, Muyun D, Rende Y (2017) Preliminary study on the ecological agriculture development model of “Pennisetum sinese Roxb-Rocky Desertification Control-Edible Mushrooms” in Guizhou Province. Agric Sci Technol 18

Shahbaz M, Kuzyakov Y, Heitkamp F (2017) Decrease of soil organic matter stabilization with increasing inputs: mechanisms and controls. Geoderma 304:76–82

Shen C, Xiong J, Zhang H, Feng Y, Lin X, Li X, Liang W, Chu H (2013) Soil pH drives the spatial distribution of bacterial communities along elevation on Changbai Mountain. Soil Biol Biochem 57:204–211

Shi T, Gill R (2005) Developing effective policies for the sustainable development of ecological agriculture in China: the case study of Jinshan County with a systems dynamics model. Ecol Econ 53:223–246

Singh BK, Dawson LA, Macdonald CA, Buckland SM (2009) Impact of biotic and abiotic interaction on soil microbial communities and functions: a field study. Appl Soil Ecol 41:239–248

Squina FM, Mort AJ, Decker SR, Prade RA (2009) Xylan decomposition by Aspergillus clavatus endo-xylanase. Protein Expr Purif 68:65–71

Stott MB, Crowe MA, Mountain BW, Smirnova AV, Hou S, Alam M, Dunfield PF (2008) Isolation of novel bacteria, including a candidate division, from geothermal soils in New Zealand. Environ Microbiol 10:2030–2041

Su JQ, Ding LJ, Xue K, Yao HY, Zhu YG (2014) Long-term balanced fertilization increases the soil microbial functional diversity in a phosphorus-limited paddy soil. Mol Ecol 24:136–150

Sun R, Zhang X-X, Guo X, Wang D, Chu H (2015) Bacterial diversity in soils subjected to long-term chemical fertilization can be more stably maintained with the addition of livestock manure than wheat straw. Soil Biol Biochem 88:9–18

Swer H, Dkhar M (2014) Influence of crop rotation and intercropping on microbial populations in cultivated fields under different organic amendments. In: Kharwar RN, Upadhyay RS, Dubey NK, Raghuwanshi R (eds) Microbial diversity and biotechnology in food security. Springer, Berlin, pp 571–580

Tian Q, Taniguchi T, Shi W-Y, Li G, Yamanaka N, Du S (2017) Land-use types and soil chemical properties influence soil microbial communities in the semiarid Loess Plateau region in China. Sci Rep 7:45289

van der Wal A, van Veen JA, Smant W, Boschker HT, Bloem J, Kardol P, van der Putten WH, de Boer W (2006) Fungal biomass development in a chronosequence of land abandonment. Soil Biol Biochem 38:51–60

Wang L, Zhang J, Li H, Yang H, Peng C, Peng Z, Lu L (2018) Shift in the microbial community composition of surface water and sediment along an urban river. Sci Total Environ 627:600–612

Weber CF, Vilgalys R, Kuske CR (2013) Changes in fungal community composition in response to elevated atmospheric CO2 and nitrogen fertilization varies with soil horizon. Front Microbiol 4:78

Wei L (2005) Culture of introduced Pennisetum sinese Roxb. Gansu Agric Sci Technol 1:027

Weller DM, Raaijmakers JM, Gardener BBM, Thomashow LS (2002) Microbial populations responsible for specific soil suppressiveness to plant pathogens. Annu Rev Phytopathol 40:309–348

White JR, Nagarajan N, Pop M (2009) Statistical methods for detecting differentially abundant features in clinical metagenomic samples. PLoS Comput Biol 5:e1000352

Wu W, Wu J, Liu X, Chen X, Wu Y, Yu S (2017) Inorganic phosphorus fertilizer ameliorates maize growth by reducing metal uptake, improving soil enzyme activity and microbial community structure. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf 143:322–329

Xu Q, Hunag Z, Wang X, Cui L (2015) Pennisetum sinese Roxb and Pennisetum purpureum Schum. as vertical-flow constructed wetland vegetation for removal of N and P from domestic sewage. Ecol Eng 83:120–124

Xun W, Xiong W, Huang T, Ran W, Li D, Shen Q, Li Q, Zhang R (2016) Swine manure and quicklime have different impacts on chemical properties and composition of bacterial communities of an acidic soil. Appl Soil Ecol 100:38–44

Yin C, Jones KL, Peterson DE, Garrett KA, Hulbert SH, Paulitz TC (2010) Members of soil bacterial communities sensitive to tillage and crop rotation. Soil Biol Biochem 42:2111–2118

Yongfen LZM (1999) Studies on EM raising the fodder value of straw of Pennisetum Sinese Roxb. J Mt Agric Biol 4

Yumoto I, Hirota K, Yamaga S, Nodasaka Y, Kawasaki T, Matsuyama H, Nakajima K (2004) Bacillus asahii sp. nov., a novel bacterium isolated from soil with the ability to deodorize the bad smell generated from short-chain fatty acids. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 54:1997–2001

Zhang Q-C, Shamsi IH, Xu D-T, Wang G-H, Lin X-Y, Jilani G, Hussain N, Chaudhry AN (2012) Chemical fertilizer and organic manure inputs in soil exhibit a vice versa pattern of microbial community structure. Appl Soil Ecol 57:1–8

Zhang W, Lu Z, Yang K, Zhu J (2017) Impacts of conversion from secondary forests to larch plantations on the structure and function of microbial communities. Appl Soil Ecol 111:73–83

Zhong W, Gu T, Wang W, Zhang B, Lin X, Huang Q, Shen W (2010) The effects of mineral fertilizer and organic manure on soil microbial community and diversity. Plant Soil 326:511–522

Acknowledgements

We thank Huilin Li, Zaijun Yang, Mingli Liao for their assistance in chemical analysis.

Funding

This work was financially supported by the National Science Foundation of China (41606142) and the Fundamental Research Funds of China West Normal University (17YC140, 416793, 416796).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

LL, CZ, and YH designed the experiment and wrote the article, and contributed equally to the paper, and YH worked on the laboratory work. CP, HL, JZ and RL helped with the soil sampling and paper discussion. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1: Fig. S1.

(A) Overview of the ecological agriculture farm. (B) Pennisetum sinese Roxb. (C) Geese feed on Pennisetum sinese Roxb. (D) Fermentation of the livestock manures. The photos were taken by Yan He. Fig. S2. The abundance of bacteria (A) and fungi (B) was significantly different in different samples (P < 0.05). Fig. S3. The second level profile of KEGG predicted by PICRUST. Fig. S4. Percentage of PICRUSt-predicted reads annotated to genes for key Nitrogen, Sulfur, Hydrogen, and Methane Glutamic and Carbon from each sequencing library. RA, percent relative abundance. Fig. S5. Relative abundance (RA) at the genus (only for Euryarchaeota) level in soil samples. Table S1. Primers and conditions used in this study.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

He, Y., Lu, L., Peng, C. et al. High-yield grass Pennisetum sinese Roxb plantation and organic manure alter bacterial and fungal communities structure in an ecological agriculture farm. AMB Expr 10, 86 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13568-020-01018-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13568-020-01018-2