Abstract

Understanding the drivers of species distribution is an important topic in conservation biology and ecology, pertaining to species traits like dispersal strategies and species–environment interactions. Here we examined the drivers of benthic species distribution at 20 sections of a second-order stream network. Environmental and spatial factors and the dispersal modes of the organisms were considered. We expected that species with aerial dispersal capabilities like insects would be less restrained by distance between sites and thus mostly affected by environmental factors. In contrast, we hypothesized that completely benthic species would mainly be affected by spatial factors due to limited dispersal. However, microscopic species like nematodes characterized by a high passive dispersal potential may be less limited by spatial factors. When using redundancy analyses and subsequent variance partitioning, the included variables explained 24% (insects), 24% (non-flying macrobenthos), and 32% (nematodes) of the variance in the respective community composition. Spatial factors mainly explained the species composition of all tested groups. In contrast with other larger species, nematodes were characterized by fine-scale patterns that might have been induced by random processes (e.g., random distribution and priority effects). Our study showed that dispersal processes are crucial in shaping benthic communities along streams albeit the relatively small sampling area (max. distance between sampling sites: 2 km). The demonstration of spatial factors as important drivers of the species distribution of passively dispersing benthic organismal groups highlights the role played by connectivity in determining species distribution patterns in river systems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Benthic metacommunities within a stream system are in continuous flux due to dispersal (Bruno et al. 2012). Thus, the linkage and spatial distribution of habitats are important spatial factors influencing community structure and dynamics (Chisholm et al. 2011; Altermatt and Fronhofer 2018; Tonkin et al. 2018). With increasing distance between communities, the dispersal limitation increases, while at shorter distances, mass effects play a larger role (Heino et al. 2015a). For benthic organisms, dispersal ability and dispersal mode are crucial determinants of species distribution (Grönroos et al. 2013; Kärnä et al. 2015; Tonkin et al. 2018; Tornero et al. 2018).

Four fundamental and taxon-specific modes of dispersal for benthic organisms have been described: (1) active and (2) passive upstream or downstream movements through the sediment or water column and (3) active and (4) passive movements over land (Palmer 1988; Bilton et al. 2001; Bohonak and Jenkins 2003). In general, passive dispersal by water currents and downstream drift is the most common mode of dispersal for all benthic invertebrates susceptible to flow velocity and direction (Lancaster et al. 1996; Bruno et al. 2012), whereas most macrobenthic taxa (organisms retained on a 500-µm mesh) are able to actively move over longer distances. For example, adult insects can cover overland distances of several hundred meters, which allows them to lay their eggs upstream or downstream or even migrate overland to other water bodies (Macneale et al. 2005; Finn and Poff 2008; Tonkin et al. 2018). Guided by chemical stimuli, some adult insects actively head to sites conducive to oviposition (Bentley and Day 1989; Blaustein et al. 2004). By contrast, their larvae as well as other non-winged macrobenthic taxa may be confined to the sediment, where they disperse along the watercourse by active upstream and downstream movements over or through the streambed as well as by short drifts (Bruno et al. 2012). Indeed, even upstream movement will allow distances between 3 and > 100 m to be covered within a single day (Elliott 2003). Nonetheless, whether there is a general upstream or downstream, taxon-specific dispersal mode remains a matter of debate (Jones and Resh 1988; Winterbourn and Crowe 2001; Petersen et al. 2004; Macneale et al. 2005).

Although meiobenthic organisms (organisms passing through a sieve of 500-µm mesh size but retained on a 44-µm mesh (Giere 2009), e.g., nematodes) actively move through the streambed and some taxa are able to swim, their dispersal mode is mainly passive (Chandler and Fleeger 1983; Palmer 1988; Ullberg and Ólafsson 2003; Thomas and Lana 2011). It has been shown that substrates placed in streams or lakes are quickly colonized by diverse and abundant nematode community through dispersal in the water column (Schmid-Araya 2000; Duft et al. 2002; Peters et al. 2007). Overland transport has also been documented involving a variety of dispersal vectors (e.g., waterbirds: Gaston 1992; Green and Figuerola 2005; footwear: Valls et al. 2016; mammals: Waterkeyn et al. 2010). Additionally, meiobenthic organisms are dispersed by wind but with a higher dispersal potential in environments linked to the source habitat (Maguire 1963; Incagnone et al. 2015; Ptatscheck et al. 2018). Due to their diverse dispersal modes, short generation times, and ability to enter resting stages, meiobenthic organisms are able to colonize aquatic habitats within a few days, through continuous and random inputs of colonists (Chandler and Fleeger 1983; Ptatscheck and Traunspurger 2014; Ptatscheck et al. 2015; Ptatscheck and Traunspurger 2015).

In addition to this dispersal based perspective, environmental factors such as resource inputs (e.g., inputs of leaf litter) and abiotic factors (e.g., oxygen content) and biotic interactions (e.g., predation) are important drivers of community composition [niche-based perspective, according to Leibold (1998) and Chase and Leibold (2009)]. In benthic stream ecosystems, substrate quality (Swan and Palmer 2000; Usseglio-Polatera et al. 2000) is also decisive, as sediment grain size and shape determine the flow velocity and shear stress at the bottom of the stream, the deposition of organic material, biofilm growth, oxygen penetration and therefore the vertical distribution of the zoobenthos (Coleman and Hynes 1970; Goulder 1971; Strommer and Smock 1989; Traunspurger et al. 2015; Majdi et al. 2017).

The dispersal ability of organisms may determine the influence of environmental factors in a given habitat (reviewed by Heino et al. 2017). Studies of the macrobenthos have shown that, depending on their dispersal mode, these organisms are differentially affected by spatial and environmental factors: The impact of environmental factors on species distribution is stronger for those species able to disperse by directed flying at a given phase of their life stage, while spatial factors (distances between communities) are the main drivers of the dispersal of metacommunities of drifting species (Grönroos et al. 2013; Heino and de Mendoza 2016; Tonkin et al. 2018).

Meiobenthos are essential for sediment mixing, nutrient cycling and energy flow in lotic systems (Covich et al. 1999; Schmid-Araya and Schmid 2000; Bergtold and Traunspurger 2005; Majdi et al. 2017). Moreover, meiobenthic organisms comprise up to 82% of benthic metazoan species (Robertson et al. 2000; Schmid-Araya et al. 2002) and include nematodes, one of the most common meiobenthic taxa, with densities as high as over one million individuals per square meter (Traunspurger 2000; Traunspurger et al. 2012). In the studies of Beier and Traunspurger (2003a, b, c), 71 and 113 nematode species were identified in a ~ 100-cm3 sediment sample (26-cm2 sediment area) obtained from two streams during a 1-year period. In contrast to the many studies focusing on the macrobenthos, the factors determining the metacommunity structure of meiobenthos in a stream network have yet to be investigated, with the exception of the study by Castillo-Escrivà et al. (2016), in which the importance of the watercourse dispersal of ostracods was reported.

The aim of the present study was to investigate the main drivers structuring meiobenthic and macrobenthic stream communities, based on samples collected from 20 sampling sites along a 10.9-km stream network. Both macrobenthos and nematodes, as representatives of the meiobenthos, were included. The two groups of organisms were classified according to their dispersal mode as follows: (1) macrobenthos with flying life stages (insect larvae), (2) non-flying macrobenthos (crustaceans, molluscs, annelids and flatworms) that spread along the water course, and (3) meiobenthos (exemplified by nematodes). In addition, spatial (overland distances) and environmental (streambed topography, food resources, and water parameters) factors were considered as potential regulators. We hypothesized (H1) that communities of insect species are mainly affected by environmental parameters, because these taxa are able to overcome larger distances and actively choose habitats suitable for colonization. By contrast, non-flying macrobenthic species are restricted by the spatial distribution of suitable habitats along the watercourse. We therefore predicted (H2) that the distance between habitats would be an important determinant of community composition of the non-flying macrobenthos. The very effective dispersal of meiobenthos reflects both active movement to propitious sites on small scales and passive drift in water or air over longer distances. Thus (H3), for nematodes, environmental factors were expected to exert a larger influence than spatial ones.

Materials and methods

Sampling sites

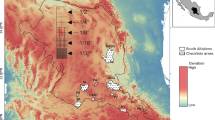

Our study was conducted in Bielefeld, Germany, in October and November 2016. Samples were obtained from along a 10.9-km stream network containing sections of the Johannisbach (JhB), Gellerhagener Bach (GhB), Grenzbach (GB), Schlosshofbach (ShB), and Sudbrackbach (SbB) streams (Fig. 1). All of the investigated streams are first- and second-order streams (Strahler stream order) and have been classified as small, fine-substrate-dominated, calcareous highland rivers. The SbB is a tributary of the ShB, both of which flow into the JhB together with the GhB and GB. The JhB is part of the Weser catchment area, which ends at the North Sea. Each of the 20 sampling sites (10-m stretches) was separated from the next by a distance of < 600 m. At the time that sampling was conducted, there was a direct watercourse connection between all sampling sites, without any interruptions caused by bank fixation or the desiccation of single-stream arms. With the exception of interruption by single streets, the riparian vegetation was continuous. However, the areas between the stream branches are residential areas.

Spatial factors

The spatial overland distance was measured using maps from Google Maps and processed with ImageJ. The results were used to obtain a distance matrix, which was then analyzed using the principal coordinates of neighbor matrices (PCNM) method (Borcard and Legendre 2002). The first PCNM vectors represented broad spatial scales, and later PCNM vectors fine-scale variations. The calculation was performed in the R environment (version 3.6.1) (R Core Team 2019) using the “pcnm” function within the vegan package (Oksanen et al. 2007). The 13 eigenvectors (PCNM1–13) with positive eigenvalues were used as spatial variables in further analyses.

Thus, the spatial predictors used to analyze community similarities were based solely on overland distances. The inclusion of overland and watercourse distances to calculate PCNM vectors would have resulted in over 20 spatial predictors. In contrast, we have only 20 sites. Further, on such a small spatial extent, the overland and watercourse distances are similar and the PCNM vectors of both distance matrices are largely correlated (e.g., PCNM vector 1 from overland and watercourse distance matrices correlate with a coefficient of − 0.93). Therefore, within this analysis, we only include overland distances, and the detailed interpretation of the influential PCNM vectors will reveal which spatial patterns are relevant and whether they reflect some watercourse patterns.

Environmental factors

The physical and chemical parameters (dissolved oxygen, conductivity, temperature, and pH) of each sampling site were measured using probes (Hanna HI 9828, Hanna Instruments, Inc., Woonsocket, Rhode Island, USA). Additionally, the cover ratio of the different substrate types was estimated according to Meier et al. (2006). The following substrate types were considered: technolithal (artificial substrates), lithal, psammal, phytal (macrophytes, moss, algae, roots from terrestrial plants) and detrital. Due to the importance of bacteria, ciliates, and flagellates as food resources for larger organisms, their biomasses were included as local variables in the multivariate analysis. Protozoans and bacteria were counted separately in 1-ml sediment samples. Protozoans were counted alive in Nageotte counting chambers (0.5 mm depth, 1.25 mm3) within 24 h after sampling. The samples were prepared in filtered (0.2-µm cellulose nitrate membrane filters, Whatman, Little Chalfont, Buckinghamshire, UK) stream water, filled to a final volume of 2 ml and vortexed for 30 s. Subsamples of 100 µl were taken from the overlaying water and transferred to the counting chamber. Counting was repeated three times per sample using a Scope A1 stereomicroscope (400×magnification; Zeiss, Jena, Deutschland), scanning the whole chamber. Ciliates and flagellates were detected by their characteristic movements and counted according to the procedure of Gasol (1993), based on size classes (< 10, 10–20, 20–30, > 30 µm for flagellates and < 25, 25–50, 50–75, 75–100, 100–125, 125–150, > 150 µm for ciliates). The data were used to calculate the specific biovolumes (V), assuming the closest geometric shape of each organism type (spheres for ciliates ≤ 50 µm and cylinders for ciliates > 50 µm and for flagellates of all size classes). Dry mass (DM) was calculated according to (Laybourn and Finlay 1976) as shown in Eq. (1):

Bacterial density was determined by the DAPI (4′, 6-diamidino-2-phenylindone) staining method of Porter and Feig (1980), modified by Schallenberg et al. (1989). Briefly, 1 ml of Millipore water and 32.3 µl of tetrasodium pyrophosphate were added to each 1 ml sediment sample in Eppendorf tubes. The samples were vortexed (5 s), placed in an ultrasonic bath (15 min, 35 kHz), and vortexed again (5 s) to separate the bacteria from the sediment. 200 µl of the supernatant was removed using a pipette and placed in a tube together with 1.8 ml of Millipore water and 0.1 ml of DAPI (50 µl/ml). After 8 min of staining in the dark, the samples were filtered on Isopore membrane filters (Millipore, 0.2 µm, 0.64 cm2). The filters were placed on slides and the number of bacterial cells on the filters counted in five randomly chosen grids (0.015 mm2) by fluorescence microscopy (Axioplan2, Zeiss, Jena, Deutschland) at 1000×magnification. For bacteria, a cell volume of 0.125 µm3 (Faupel et al. 2011) and a derived DM of 1.09 g cm−3 and 30% dry content (Bakken and Olsen 1983) were assumed.

Sampling, counting, and classification of meiobenthos

As organisms in fine sediments (< 1 mm) are mainly distributed in the upper layers, meiobenthos sampling was restricted to the upper 5 cm of the streambed. A corer (2.6 cm diameter) was used to obtain five samples per site, which were then pooled (132.5 cm3 of sediment, n = 1). A 4 ml subsample (sediment and pore water) extracted from each sediment sample using a pipette (one/sample) was used to count protozoans and bacteria. From the rest of the sample, meiobenthos were extracted by density centrifugation (LudoxTM50, Sigma-Aldrich, Munich, Germany; 1.14 g ml−1, mesh size 10 µm) according to Pfannkuche and Thiel (1988), stained with rose Bengal (AppliChem, Darmstadt, Germany) and then preserved in formaldehyde (final concentration: 4%). The whole sample was placed in a gridded Petri dish, and the organisms were counted under a Leica L2 stereomicroscope (40×magnification; Leica, Wetzlar, Germany). Fifty nematodes per sample were prepared after Seinhorst (1959, 1962) and then identified to the species level based on Leica Dialux microscopy observations (1250× magnification) mainly according to the criteria of Andrássy (2005, 2007, 2009), Loof et al. (1999) and Loof et al. (2001).

Sampling, counting, and classification of macrobenthos

Macrobenthos was sampled using the standardized method of Meier et al. (2006), developed for use in compliance with the EU-Water Framework Directive. Each sampling site consisted of 1.25 m2 of sediment. The samples were obtained by kick sampling, using a landing net (500-µm mesh size, 25 × 25 cm edge length). One sample consisted of 20 pooled (n = 1) subsamples (~ 0.06 m2 each), with the composition of the sampled sediment based on the covering ratio of the substrate type. Alternatively, the collection of macrobenthos from removed stones, wood or macrophytes replaced single subsamplings with the net. The collected organisms were pre-sorted, counted in the field and a relevant number of individuals (6–50) per taxon (see Meier et al. 2006) then fixed in 85% ethanol. For the classification to the species level, the organisms (insect larvae, crustaceans, molluscs, annelids, and flatworms) were observed under a Leica L2 stereomicroscope (40× magnification).

Data analysis

Only taxa identified to species level were used for the statistical analysis. A detrended correspondence analysis (DCA) was used to check the length of the main gradients for the communities of the three groups defined in the Introduction (insects, non-flying macrobenthos, nematodes). As the total inertia was < 2.6 for all three analyses, a predominance of linear response curves was expected (ter Braak 1994). Therefore, redundancy analyses (RDAs) were performed using presence/absence data to analyze the relationships between species distributions in the three groups and the following categories of variables: (1) the spatial position of sites using the PCNM vectors and (2) environmental variables that may affect faunal distributions, including water parameters (dissolved oxygen, conductivity, temperature, and pH), the biomass of microbial resources in the sediment (ciliates, flagellates, and bacteria) and the topology of the streambed (defined as the relative contributions of the recognized substrate types listed above). Some environmental predictors were correlated. These were conductivity with temperature and pH, biomass of flagellates and ciliates, and oxygen and detrital (for all cor > 0.6, p < 0.001). Following Blanchet et al. (2008), we excluded strongly correlated variables prior to the calculation of RDAs. Therefore, we excluded the factors temperature, pH, biomass of ciliates, and detrital.

RDA models with the set of environmental variables that best explained the species compositions were selected through a stepwise process (“rda” and “ordistep” function in vegan package, model choice comparing AIC scores). Permutation tests were used to assess the significance of the RDAs (999 permutations). Using the set of spatial and local variables significantly associated with species distributions, we conducted a partial redundancy analysis (pRDA, “varpart” function) to partition the explanation of variance with respect to variable groups. The adjusted R2 of the pRDA was applied to assess the partitions explained by the explanatory variables and their combinations (Peres-Neto et al. 2006). All analyses were performed under the R computational framework version 3.6.1 (R Core Team 2019).

Results

Benthos composition

Among the 164,174.7 (mean ± 189,739.7) individuals collected per square meter of the streambed, 98.1% (mean ± 2.4%) were members of the meiobenthos (Table 1). The meiobenthos was dominated by rotifers (49.1%) and nematodes (37.5%), while crustaceans (50.9%) were the largest contributors to the macrobenthos. Seventy-three nematode species and 45 macrobenthos species were included in the statistical analysis. Because we were unable to identify either chironomid larvae or oligochaete members of the tubificidae to the species level, these taxa were not considered for the statistical analysis. Fourteen of the 45 macrobenthic species were classified as non-flying and 31 as flying macrobenthos (Table 1), with trichopterans and coleopterans showing the highest species diversity.

Influence of spatial and environmental factors

The RDA analysis showed that the spatial positions of the sampling sites and the streambed topography were significant determinants of the species distribution of all tested groups (Table 2). For insects, the range of significant PCNMs was wider than for non-flying macrobenthos and nematodes. While PCNM1, PCNM2, PCNM3 PCNM7, and PCNM8 were significant for insects, only PCNM1 and PCNM2 had a significant effect on non-flying macrobenthos as well as PCNM4 and PCNM12 on nematodes. PCNM1 and PCNM2 reflect clear large-scale patterns of similar benthic compositions (Fig. 2). At the latest by PCNM4, these patterns became more small scale.

Sampling sites along the stream network with a subset of PCNMs significant for insects (PCNM1, PCNM2, PCNM3, PCNM7, PCNM8), non-flying macrobenthos (PCNM1, PCNM2) and nematodes (PCNM4, PCNM12). The color gradient from white over brown to black indicates the values of the respective PCNM vector at the sampling sites and therefore indicates the spatial pattern that is represented by each PCNM vector. Values are continuous, and the three groups are artificially set to make patterns visible

In addition to the spatial distribution of the sampling sites along the stream network, fine substrates (psammal), potential microbial food resources (flagellates), and physical and chemical parameters of water (dissolved oxygen) played a role in shaping benthic communities of insects. Contrary, environmental factors had no effect on non-flying macrobenthos and nematodes.

Variance partitioning

All the included variables together explained 24% of the variance in insect species composition at the 20 sampling sites. For non-flying macrobenthos and for nematodes, the corresponding values were 24% and 32%, respectively (Table 3). Thus, with residuals of 68%, the variance explanation for nematodes was higher than that for both macrobenthic groups. For insects, spatial factors explained a higher proportion of the variance than environmental factors, but the fraction was not significant indicating a clearer relation of environmental factors and insect community assembly than with spatial factors. The shared effects of environmental and spatial factors did not explain any of the variance in the species community; in fact, the values were slightly negative which can happen when the matrices are not correlated (Legendre et al. 2012). This is also the reason why the sum of the individual fractions of environmental and spatial predictors is not exactly the same as the overall explained variance. Nevertheless, the small negative values indicated that relevant environmental factors were not spatially structured according to the included PCNMs.

Discussion

This study assessed the impact of environmental and spatial factors on the benthic species composition in streams, assuming different dispersal modes in these groups of organisms. It is the first study to include meiobenthic organisms, which were then compared with macrobenthic taxa. Among the tested factors potentially shaping the species distributions of the three groups of organisms (insects, non-flying macrobenthos and nematodes), spatial factors explained the major part of the variances in their respective community composition. However, the pure spatial fraction was not significant for insects in the variance partitioning analysis. Those results partially supported two of our starting hypotheses as we assumed that insect species would be mainly affected by environmental parameters (H1) and that non-flying macrobenthic species would be mainly restricted by the spatial distribution of suitable habitats (H2). However, the significant association of nematode distribution and spatial parameters contradicts our hypothesis that nematode species would be insensitive to spatial parameters given their extremely high dispersal capabilities (H3).

The role of spatial factors

The maximal overland distance between two sampling sites was 2 km, but in most cases, the distances were shorter. Malmqvist (2002) observed that imagos of stream-living insects can cover distances of several kilometers but are ultimately limited in their spatial distribution by factors that include geographic conditions (e.g., mountain ranges), vegetation (e.g., forests, open land, land use), or wind (Briers et al. 2004; Tonkin et al. 2018). Similar dispersal barriers did not occur in our relatively small study area (but see below). Further, taking into account the studies of Kovats et al. (1996) and Geismar et al. (2015) on dispersal range, an exchange of flying insects between the stream sites investigated in our study was possible, which implies a degree of dispersal for this organismal group that was high enough to allow the tracking of favorable environmental gradients as indicated by the significant influence of pure environmental predictors on insect community structures (Table 3). In contrast, the trend of a spatial structure of insect communities was not significant (Table 3), and therefore, these results have to be treated cautiously. However, this spatial structure is more likely to be attributable to mass effects than to dispersal limitations due to the high mobility of insects in the small sampling area. Other studies have also found fewer indications of dispersal limitations (variance explained by pure spatial variables < 3%) for insects, even though larger spatial extents were investigated (e.g., > 30,000 km2 in de Bie et al. 2012, hundreds of km in Grönroos et al. 2013). Our study is one of the few to provide evidence of mass effects (Leibold and Chase 2017), probably due to its smaller spatial extent compared to other metacommunity studies. However, our study was conducted in an urban environment, where pathways for overland dispersal may be hampered. Such that small water bodies as stopovers for dispersal are missing (Incagnone et al. 2015), and the availability of potential dispersal vectors (e.g., birds: Gaston 1992) is low.

While for insects overland dispersal was expected to represent an important dispersal pathway, for non-flying macrobenthos, the watercourse was expected to serve as the principal dispersal corridor (Tonkin et al. 2018). We found a strong spatial signal in the metacommunity patterns of non-flying macrobenthos. This finding was in accordance with other studies and with our starting hypothesis (H2), in which the influence of spatial components on community structures was deduced to dispersal limitations of passively dispersing aquatic macroinvertebrates (de Bie et al. 2012; Heino 2013; Rádková et al. 2014). Nevertheless, the very large contribution of pure spatial factors to the explained variance was surprising, especially given the small spatial extent of our study (< 11 km). A possible explanation of the large spatial influence albeit the small study extent would be the preponderance of mass effects overriding environmental influence. Contradicting the suggestion of dispersal limitation for this organismal group are also the results of Grönroos et al. (2013) who found no spatial signal in the distribution of non-flying macroinvertebrates, despite the large spatial extent of their study. They explained their finding by the potentially high dispersal rates of these organisms attributable to larger animals, such as water fowl (Charalambidou and Santamaría 2005; Green and Figuerola 2005). Also, Vanschoenwinkel et al. (2008) demonstrated that, e.g., turbellaria can be passively transported by wind. Further, Grönroos et al. (2013) pointed out that the low number of species (in this case 23) included in their analysis could lead to unexpected results. In our study, non-flying macroinvertebrates were represented by only 14 species. With regard to this low number of species, the characteristic of each species included is more relevant than in a group with a larger number of species as for nematodes and insects in our study. Thus, the metacommunity structures might have been very different if they had been grouped as specialists/generalists or as common/rare species (Rádková et al. 2014).

Nematode composition along the investigated river network was explained by spatial factors, which refuted our third hypothesis (H3). For the dispersal of meiobenthos, especially nematodes, both passive overland transport by larger animals or wind and distribution within the water are essential mechanisms (Williams and Hynes 1976; Williams 1977; Frisch et al. 2007; Incagnone et al. 2015; Ptatscheck et al. 2018). Thus, in our study, continuous inputs of nematodes from inside and outside the stream were expected to occur at all sampling sites. Different dispersal modes were reported for other meiobenthic organisms like ostracods by Castillo-Escrivà et al. (2016), who identified watercourse distances as the sole main driver of community structure. Various dispersal modes for different meiobenthic taxa can likewise be suggested, perhaps reflecting specific means of locomotion or behaviors (e.g., vertical distribution) that lessen the contribution of water drift (reviewed by Palmer 1988) or limit passive dispersal (Incagnone et al. 2015). However, the high dispersal potential of meiobenthos is intrinsic to the effective colonization by these organisms of aquatic habitats (Chandler and Fleeger 1983; Schmid-Araya 2000; Peters et al. 2007; Ptatscheck et al. 2018), with passive dispersal resulting in rather random colonization processes (Ptatscheck et al. 2015; Ptatscheck and Traunspurger 2015). Invading species may be precluded from a site by the already established communities (Shurin 2000). In this case, a priority effect (early colonizers affect the colonization probability of species arriving later into a patch) would cause differences in the species assemblages (Urban and de Meester 2009). Since this effect is based on a random process, the pattern of the metacommunity structure would be random as well. While the macrobenthic composition was explained only by broad-scale spatial eigenvectors (PCNM1 and PCNM2), for nematodes only small-scale eigenvectors (PCNM4 and PCNM12) were significant, indicating that dispersal limitations were not the cause of the spatial structure of nematode distribution (Heino et al. 2015a). Thus, this finding is in accordance with the initially expectation of a high dispersal potential of freshwater nematodes in lotic systems. The clustering of nematodes in patches of an area restricted to a few square centimeters of sediment was previously reported by Gallucci et al. (2009) and Gansfort et al. (2018) and the studies listed therein. Such fine-scale distribution also supports the importance of fine rather than large-scale spatial autocorrelation albeit due to the larger grid sampling design also the fine-scale PCNMs do not refer to a centimeter scale.

We only included overland distances into our analysis. Therefore, we cannot distinguish between the importance of overland and watercourse dispersal pathways, and this was not the objective of this study. Due to the small spatial extent of our sampling sites, overland and watercourse distances are relatively similar and therefore the PCNM vectors correspond also to watercourse distances (see Fig. 2).

The role of environmental factors

Our results indicate that, along with spatial factors, environmental factors (streambed topography, food resources, and water parameters) significantly shape the density distribution of insects. In contrast to a previous report (Swan and Palmer 2000), we found no evidence of an influence of environmental parameters on non-flying macrobenthos and nematodes. However, we are not able to distinguish whether the absence of a relation between environmental factors and community structure in these two groups was due to (1) dispersal limitation because of species not reaching suitable sites, (2) mass effects which can decrease community heterogeneity and therefore mask the environmental effects (summarized by Heino et al. 2015b, 2017), or (3) the relatively short gradient of environmental conditions due to the small sampling area.

Previous studies identified the specific quality (e.g., grain size and surface texture) and occurrence of different substrates as the main drivers of macroinvertebrate species composition in stream ecosystems (Cummins and Lauff 1969; Hax and Golladay 1993; Wallace et al. 1995; Vinson and Hawkins 1998). These studies show that substrates shape the benthic community by providing food resources, additional breeding ground, and refuge from predation, as well as by reducing stream velocity and thus the risk of downstream drift. This was also the case in our study with psammal substrate having a significant effect on the insect community. Low velocity and streambed topography (e.g., grain size) mainly affect the accumulation of detritus (Rabeni and Minshall 1977; Eedy and Giberson 2007), while fine sediments (e.g., psammal) in low-flow areas can retain fine organic material. The decisive importance of detritus as a structural element of streambeds that provides a habitat and food resource for benthic organisms (insects and non-flying taxa) has been demonstrated in several studies (Levin and Paine 1974; Flecker 1984; Reice 1991; Lancaster and Downes 2014). However, the benefits of detritus are strongly species specific and vary throughout the year (Flecker 1984; Mancinelli et al. 2005; Rabení et al. 2005). In general, the diet of a wide range of benthic invertebrates consists of organic material (Cummins 1974), which is also the main component of their gut contents (Schmid-Araya and Schmid 1995, 2000; Schmid and Schmid-Araya 1997; Tavares-Cromar and Williams 1997; de Carvalho and Uieda 2009). In our study, detritus was highly negatively correlated with the oxygen content of the sediment and therefore possibly important for shaping the insect community structure (Table 3). Also, the biomass of protozoans (flagellates), representing an integrative indicator of food resources, was found to significantly affect the species distribution of insects. Unicellular organisms are a crucial compartment of the benthic food web (Cummins 1973; Borchardt and Bott 1995; Bott and Borchardt 1999; Schmid-Araya and Schmid 2000).

General discussion and conclusion

Our results are based on a comprehensive data set, and they identified the factors driving benthic species distribution, but they represent only a small window of time. For example, passive dispersal by wind may greatly vary depending on seasonal factors related to wind speed and humidity (Incagnone et al. 2015; Ptatscheck et al. 2018). Strong precipitation will increase the velocity of streams, while drought can alter the connections within a river network. Both may change the watercourse-mediated dispersal of benthic organisms. In addition, the oviposition of flying insects is seasonally restricted. Thus, the relative impact of the investigated factors may change during the course of the year, consistent with the strong temporal component shown to characterize nematode metacommunities (Gansfort and Traunspurger 2019). Furthermore, although our study included a direct comparison between meio- and macrobenthic taxa, investigations of other meiobenthic groups, such as rotifers and other microcrustaceans, are needed to provide a complete understanding of the processes affecting invertebrate biodiversity in lotic systems.

In conclusion, our results highlight the roles played by environmental and spatial factors affecting benthic biodiversity in lotic systems. Although food resources and streambed topography were identified as important environmental factors for the insect community, especially the spatial arrangement of the sampling sites, dispersal-related factors were strong determinants of the composition of the benthic invertebrate community. Our study demonstrates the importance of spatial parameters at shaping communities of benthic invertebrates over relatively small distances (kilometer scale). Previous studies also showed that connectivity along the flow length and the presence of a continuous riparian vegetation shape biological processes (Pusch et al. 1998) and increase the diversity of stream-living organisms (Bonada et al. 2006). Even at relatively small scale, our results suggest that land-use actions that result in habitat fragmentation may have effects on diversity of a wide range of benthic organisms. This should be taken into account in decision-making aimed at improving environmental management processes.

References

Altermatt F, Fronhofer EA (2018) Dispersal in dendritic networks: ecological consequences on the spatial distribution of population densities. Freshw Biol 63:22–32. https://doi.org/10.1111/fwb.12951

Andrássy I (2005) Free-living nematodes of Hungary (Nematoda errantia). Pedozoologica Hungarica, vol I. Hungarian Natural History Museum, Budapest

Andrássy I (2007) Free-living nematodes of Hungary (Nematoda errantia). Pedozoologica Hungarica, vol II. Hungarian Natural History Museum, Budapest

Andrássy I (2009) Free-living nematodes of Hungary (Nematoda errantia). Pedozoologica Hungarica, vol III. Hungarian Natural History Museum, Budapest

Bakken LR, Olsen RA (1983) Buoyant densities and dry-matter contents of microorganisms: conversion of a measured biovolume into biomass. Appl Environ Microb 45:1188–1195

Beier S, Traunspurger W (2003a) Seasonal distribution of free-living nematodes in the Körsch, a coarse-grained submountain carbonate stream in southwest Germany. Nematology 5:481–504. https://doi.org/10.1163/156854103322683229

Beier S, Traunspurger W (2003b) Seasonal distribution of free-living nematodes in the Krähenbach, a fine-grained submountain carbonate stream in southwest Germany. Nematology 5:113–136. https://doi.org/10.1163/156854102765216740

Beier S, Traunspurger W (2003c) Temporal dynamics of meiofauna communities in two small submountain carbonate streams with different grain size. Hydrobiologia 498:107–131. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1026258607551

Bentley MD, Day JF (1989) Chemical ecology behavioral aspects of mosquito oviposition. Ann Rev Entomol 34:401–421. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.en.34.010189.002153

Bergtold M, Traunspurger W (2005) Benthic production by micro-, meio-, and macrobenthos in the profundal zone of an oligotrophic lake. J N Am Benthol Soc 24:321–329. https://doi.org/10.1899/03-038.1

Bilton DT, Freeland JR, Okamura B (2001) Dispersal in freshwater invertebrates. Annu Rev Ecol Syst 32:159–181. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.32.081501.114016

Blanchet FG, Legendre P, Borcard D (2008) Modelling directional spatial processes in ecological data. Ecol Model 215:325–336. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolmodel.2008.04.001

Blaustein L, Kiflawi M, Eitam A, Mangel M, Cohen JE, Blaustein L, Kiflawi M, Eitam A, Mangel M, Cohen JE (2004) Oviposition habitat selection in response to risk of predation in temporary pools: mode of detection and consistency across experimental venue. Oecologia 138:300–305. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00442-003-1398-x

Bohonak AJ, Jenkins DG (2003) Ecological and evolutionary significance of dispersal by freshwater invertebrates. Ecol Lett 6:783–796. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1461-0248.2003.00486.x

Bonada N, Rieradevall M, Prat N, Resh VH (2006) Benthic macroinvertebrate assemblages and macrohabitat connectivity in Mediterranean-climate streams of northern California. J N Am Benthol Soc 25:32–43. https://doi.org/10.1899/0887-3593(2006)25%5b32:bmaamc%5d2.0.co;2

Borcard D, Legendre P (2002) All-scale spatial analysis of ecological data by means of principal coordinates of neighbour matrices. Ecol Model 153:51–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0304-3800(01)00501-4

Borchardt MA, Bott TL (1995) Meiofaunal grazing of bacteria and algae in a Piedmont stream. J N Am Benthol Soc 14:278–298. https://doi.org/10.2307/1467780

Bott TL, Borchardt MA (1999) Grazing of protozoa, bacteria, and diatoms by meiofauna in lotic epibenthic communities. J N Am Benthol Soc 18:499–513. https://doi.org/10.2307/1468382

Briers RA, Gee JHR, Cariss HM, Geoghegan R (2004) Inter-population dispersal by adult stoneflies detected by stable isotope enrichment. Freshw Biol 49:425–431. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2427.2004.01198.x

Bruno MC, Bottazzi E, Rossetti G (2012) Downward, upstream or downstream? assessment of meio- and macrofaunal colonization patterns in a gravel-bed stream using artificial substrates. Ann Limnol-Int J Lim 48:371–381. https://doi.org/10.1051/limn/2012025

Castillo-Escrivà A, Rueda J, Zamora L, Hernández R, Moral Md, Mesquita-Joanes F (2016) The role of watercourse versus overland dispersal and niche effects on ostracod distribution in Mediterranean streams (eastern Iberian Peninsula). Acta Oecol 73:1–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actao.2016.02.001

Chandler GT, Fleeger JW (1983) Meiofaunal colonization of azoic estuarine sediment in Louisiana: mechanisms of dispersal. J Exp Mar Biol Ecol 69:175–188. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-0981(83)90066-7

Charalambidou I, Santamaría L (2005) Field evidence for the potential of waterbirds as dispersers of aquatic organisms. Wetlands 25:252–258

Chase JM, Leibold MA (2009) Ecological niches: linking classic and contemporary approaches. Interspecific interactions. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Chisholm C, Lindo Z, Gonzalez A (2011) Metacommunity diversity depends on connectivity and patch arrangement in heterogeneous habitat networks. Ecography 34:415–424. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0587.2010.06588.x

Coleman MJ, Hynes HBN (1970) The vertical distribution of the invertebrate fauna in the bed of a stream. Limnol Oceanogr 15:31–40. https://doi.org/10.4319/lo.1970.15.1.0031

Covich AP, Palmer MA, Crowl TA (1999) The role of benthic invertebrate species in freshwater ecosystems. Bioscience 49:119. https://doi.org/10.2307/1313537

Cummins KW (1973) Trophic relation of aquatic insects. Ann Rev Entomol 18:183–206

Cummins KW (1974) Structure and function of stream ecosystems. Bioscience 24:631–641. https://doi.org/10.2307/1296676

Cummins KW, Lauff GH (1969) The influence of substrate particle size on the microdistribution of stream macrobenthos. Hydrobiologia 34:145–181. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00141925

de Bie T, de Meester L, Brendonck L, Martens K, Goddeeris B, Ercken D, Hampel H, Denys L, Vanhecke L, van der Gucht K, van Wichelen J, Vyverman W, Declerck SAJ (2012) Body size and dispersal mode as key traits determining metacommunity structure of aquatic organisms. Ecol Lett 15:740–747. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1461-0248.2012.01794.x

de Carvalho EM, Uieda VS (2009) Diet of invertebrates sampled in leaf-bags incubated in a tropical headwater stream. Zoologia 26:694–704

Duft M, Fittkau K, Traunspurger W, Fittkau S (2002) Colonization of exclosures in a Costa Rican Stream: effects of Macrobenthos on Meiobenthos and the Nematode Community. J Fresw Ecol 17:531–541. https://doi.org/10.1080/02705060.2002.9663931

Eedy RI, Giberson DJ (2007) Macroinvertebrate distribution in a reach of a north temperate eastern Canadian river: relative importance of detritus, substrate and flow. Fund Appl Limnol 169:101–114. https://doi.org/10.1127/1863-9135/2007/0169-0101

Elliott JM (2003) A comparative study of the dispersal of 10 species of stream invertebrates. Freshw Biol 48:1652–1668. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2427.2003.01117.x

Faupel M, Ristau K, Traunspurger W (2011) Biomass estimation across the benthic community in polluted freshwater sediment—a promising endpoint in microcosm studies? Ecotoxicol Environ Saf 74:1942–1950. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoenv.2011.06.022

Finn DS, Poff NL (2008) Emergence and flight activity of alpine stream insects in two years with contrasting winter snowpack. Arct Antarct Alp Res 40:638–646. https://doi.org/10.1657/1523-0430(07-072)%5bfinn%5d2.0.co;2

Flecker AS (1984) The effects of predation and detritus on the structure of a stream insect community: a field test. Oecologia 64:300–305. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00379125

Frisch D, Green AJ, Figuerola J (2007) High dispersal capacity of a broad spectrum of aquatic invertebrates via waterbirds. Aquat Sci 69:568–574. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00027-007-0915-0

Gallucci F, Moens T, Fonseca G (2009) Small-scale spatial patterns of meiobenthos in the Arctic deep sea. Mar Biodiv 39:9–25. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12526-009-0003-x

Gansfort B, Traunspurger W (2019) Environmental factors and river network position allow prediction of benthic community assemblies: a model of nematode metacommunities. Sci Rep 9:601. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-51245-2

Gansfort B, Traunspurger W, Threis I, Majdi N (2018) Wide variation in a tiny space: the microdistribution of meiobenthos in an artificial pond. Freshw Biol 63:420–431. https://doi.org/10.1111/fwb.13078

Gasol JM (1993) Benthic flagellates and ciliates in fine freshwater sediments: calibration of a live counting procedure and estimation of their abundances. Microb Ecol 25:247–262. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00171891

Gaston GR (1992) Green-winged teal ingest epibenthic meiofauna. Estuaries 15:227. https://doi.org/10.2307/1352696

Geismar J, Haase P, Nowak C, Sauer J, Pauls SU (2015) Local population genetic structure of the montane caddisfly Drusus discolor is driven by overland dispersal and spatial scaling. Freshw Biol 60:209–221. https://doi.org/10.1111/fwb.12489

Giere O (2009) Meiobenthology: the microscopic motile fauna of aquatic sediments, 2nd edn. Springer, Berlin

Goulder R (1971) Vertical distribution of some ciliated protozoa in two freshwater sediments. Oikos 22:199. https://doi.org/10.2307/3543725

Green AJ, Figuerola J (2005) Recent advances in the study of long-distance dispersal of aquatic invertebrates via birds. Divers Distrib 11:149–156. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1366-9516.2005.00147.x

Grönroos M, Heino J, Siqueira T, Landeiro VL, Kotanen J, Bini LM (2013) Metacommunity structuring in stream networks: roles of dispersal mode, distance type, and regional environmental context. Ecol Evol 3:4473–4487. https://doi.org/10.1002/ece3.834

Hax CL, Golladay SW (1993) Macroinvertebrate colonization and biofilm development on leaves and wood in a boreal river. Freshw Biol 29:79–87. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2427.1993.tb00746.x

Heino J (2013) Does dispersal ability affect the relative importance of environmental control and spatial structuring of littoral macroinvertebrate communities? Oecologia 171:971–980. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00442-012-2451-4

Heino J, de Mendoza G (2016) Predictability of stream insect distributions is dependent on niche position, but not on biological traits or taxonomic relatedness of species. Ecography 39:1216–1226. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecog.02034

Heino J, Melo AS, Siqueira T, Soininen J, Valanko S, Bini LM (2015a) Metacommunity organisation, spatial extent and dispersal in aquatic systems: patterns, processes and prospects. Freshw Biol 60:845–869. https://doi.org/10.1111/fwb.12533

Heino J, Melo AS, Bini LM (2015b) Reconceptualising the beta diversity-environmental heterogeneity relationship in running water systems. Freshw Biol 60:223–235. https://doi.org/10.1111/fwb.12502

Heino J, Alahuhta J, Ala-Hulkko T, Antikainen H, Bini LM, Bonada N, Datry T, Erős T, Hjort J, Kotavaara O, Melo AS, Soininen J (2017) Integrating dispersal proxies in ecological and environmental research in the freshwater realm. Environ Rev 25:334–349. https://doi.org/10.1139/er-2016-0110

Incagnone G, Marrone F, Barone R, Robba L, Naselli-Flores L (2015) How do freshwater organisms cross the “dry ocean”? A review on passive dispersal and colonization processes with a special focus on temporary ponds. Hydrobiologia 750:103–123. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10750-014-2110-3

Jones TS, Resh VH (1988) Movements of adult aquatic insects along a Montana (USA) springbrook. Aquat Insects 10:99–104. https://doi.org/10.1080/01650428809361317

Kärnä O-M, Grönroos M, Antikainen H, Hjort J, Ilmonen J, Paasivirta L, Heino J (2015) Inferring the effects of potential dispersal routes on the metacommunity structure of stream insects: as the crow flies, as the fish swims or as the fox runs? J Anim Ecol 84:1342–1353. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2656.12397

Kovats Z, Ciborowski JAN, Corkum L (1996) Inland dispersal of adult aquatic insects. Freshw Biol 36:265–276. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2427.1996.00087.x

Lancaster J, Downes BJ (2014) Population densities and density-area relationships in a community with advective dispersal and variable mosaics of resource patches. Oecologia 176:985–996. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00442-014-3062-z

Lancaster J, Hildrew AG, Gjerlov C (1996) Invertebrate drift and longitudinal transport processes in streams. Can J Fish Aquat Sci 53:572–582. https://doi.org/10.1139/f95-217

Laybourn J, Finlay BJ (1976) Respiratory energy losses related to cell weight and temperature in ciliated protozoa. Oecologia 24:349–355. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00381141

Legendre P, Borcard D, Roberts DW (2012) Variation partitioning involving orthogonal spatial eigenfunction submodels. Ecology 93:1234–1240. https://doi.org/10.1890/11-2028.1

Leibold MA (1998) Similarity and local co-existence of species in regional biotas. Evol Ecol 12:95–110. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1006511124428

Leibold MA, Chase JM (2017) Metacommunity ecology. Monographs in population biology ser, vol 59. Princeton University Press, Princeton

Levin SA, Paine RT (1974) Disturbance, patch formation, and community structure. Proc Natl Acad Sci 71:2744–2747. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.71.7.2744

Loof PAA, Brauer A, Schwoerbel J, Zwick P (1999) Nematoda: Adenophorea (Dorylaimida), 1. Aufl. Süßwasserfauna von Mitteleuropa Nematoda, Nematomorpha, 2/2. Spektrum Akad. Verl., Heidelberg

Loof PAA, Brauer A, Schwoerbel J, Zwick P (2001) Nematoda: Secernentea (Tylenchida, Aphelenchida), 1. Aufl. Süßwasserfauna von Mitteleuropa Nematoda, Nematomorpha, 1/1. Spektrum Akad. Verl., Heidelberg

Macneale KH, Peckarsky BL, Likens GE (2005) Stable isotopes identify dispersal patterns of stonefly populations living along stream corridors. Freshw Biol 50:1117–1130. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2427.2005.01387.x

Maguire B (1963) The passive dispersal of small aquatic organisms and their colonization of isolated bodies of water. Ecol Monogr 33:161–185. https://doi.org/10.2307/1948560

Majdi N, Threis I, Traunspurger W (2017) It’s the little things that count: meiofaunal density and production in the sediment of two headwater streams. Limnol Oceanogr 62:151–163. https://doi.org/10.1002/lno.10382

Malmqvist B (2002) Aquatic invertebrates in riverine landscapes. Freshw Biol 47:679–694. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2427.2002.00895.x

Mancinelli G, Sabetta L, Basset A (2005) Short-term patch dynamics of macroinvertebrate colonization on decaying reed detritus in a Mediterranean lagoon (Lake Alimini Grande, Apulia, SE Italy). Mar Biol 148:271–283. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00227-005-0091-5

Meier C, Haase P, Rolauffs P, Schindehütte K, Franz S, Sundermann A, Daniel H (2006) Methodisches Handbuch Fließgewässerbewertung: Handbuch zur Untersuchung und Bewertung von Fließgewässern auf der Basis des Makrozoobenthos vor dem Hintergrund der EG-Wasserrahmenrichtlinie. http://www.fliessgewaesserbewertung.de/downloads/abschlussbericht_20060331_anhang_IX.pdf

Oksanen J, Kindt RL, Legendre P, O’Hara B, Simpson GL, Solymos P, Henry M, Stevens H, Wagner H (2007) The vegan package. Community Ecol Package 10:631–637

Palmer MA (1988) Dispersal of marine meiofauna: a review and conceptual model explaining passive transport and active emergence with implications for recruitment. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 48:81–91

Peres-Neto PR, Legendre P, Dray S, Borcard D (2006) Variation partitioning of species data matrices: estimation and comparison of fractions. Ecology 87:2614–2625. https://doi.org/10.1890/0012-9658(2006)87%5b2614:vposdm%5d2.0.co;2

Peters L, Wetzel MA, Traunspurger W, Rothhaupt K-O (2007) Epilithic communities in a lake littoral zone: the role of water-column transport and habitat development for dispersal and colonization of meiofauna. J N Am Benthol Soc 26:232–243. https://doi.org/10.1899/0887-3593(2007)26%5b232:eciall%5d2.0.co;2

Petersen I, Masters Z, Hildrew AG, Ormerod SJ (2004) Dispersal of adult aquatic insects in catchments of differing land use. J Appl Ecol 41:934–950. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0021-8901.2004.00942.x

Pfannkuche O, Thiel H (1988) Sample processing. In: Higgins RP, Thiel H (eds) Introduction to the study of meiofauna. Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington, DC, pp 134–145

Porter KG, Feig YS (1980) The use of DAPI for identifying and counting aquatic microflora1. Limnol Oceanogr 25:943–948. https://doi.org/10.4319/lo.1980.25.5.0943

Ptatscheck C, Traunspurger W (2014) The meiofauna of artificial water-filled tree holes: colonization and bottom-up effects. Aquat Ecol 48:285–295. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10452-014-9483-2

Ptatscheck C, Traunspurger W (2015) Meio- and macrofaunal communities in artificial water-filled tree holes: effects of seasonality, physical and chemical parameters, and availability of food resources. PLoS ONE 10:e0133447. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0133447

Ptatscheck C, Dümmer B, Traunspurger W (2015) Nematode colonisation of artificial water-filled tree holes. Nematology 17:911–921. https://doi.org/10.1163/15685411-00002913

Ptatscheck C, Gansfort B, Traunspurger W (2018) The extent of wind-mediated dispersal of small metazoans, focusing nematodes. Sci Rep 8:6814. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-24747-8

Pusch M, Fiebig D, Brettar I, Eisenmann H, Ellis BK, Kaplan LA, Lock MA, Naegeli MW, Traunspurger W (1998) The role of micro-organisms in the ecological connectivity of running waters. Freshw Biol 40:453–495. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2427.1998.00372.x

R Core Team (2019) R: a language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. https://www.R-project.org/

Rabeni CF, Minshall GW (1977) Factors affecting microdistribution of stream benthic insects. Oikos 29:33. https://doi.org/10.2307/3543290

Rabení CF, Doisy KE, Zweig LD (2005) Stream invertebrate community functional responses to deposited sediment. Aquat Sci 67:395–402. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00027-005-0793-2

Rádková V, Bojková J, Křoupalová V, Schenková J, Syrovátka V, Horsák M (2014) The role of dispersal mode and habitat specialisation in metacommunity structuring of aquatic macroinvertebrates in isolated spring fens. Freshw Biol 59:2256–2267. https://doi.org/10.1111/fwb.12428

Reice SR (1991) Effects of detritus loading and fish predation on leafpack breakdown and benthic macroinvertebrates in a woodland stream. J N Am Benthol Soc 10:42–56

Robertson AL, Rundle SD, Schmid-Araya JM (2000) Putting the meio- into stream ecology: current findings and future directions for lotic meiofaunal research. Freshw Biol 44:177–183. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2427.2000.00592.x

Schallenberg M, Kalff J, Rasmussen JB (1989) Solutions to problems in enumerating sediment bacteria by direct counts. Appl Environ Microbiol 55:1214–1219

Schmid PE, Schmid-Araya JM (1997) Predation on meiobenthic assemblages: resource use of a tanypod guild (Chironomidae, Diptera) in a gravel stream. Freshw Biol 38:67–91. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2427.1997.00197.x

Schmid-Araya JM (2000) Invertebrate recolonization patterns in the hyporheic zone of a gravel stream. Limnol Oceanogr 45:1000–1005. https://doi.org/10.4319/lo.2000.45.4.1000

Schmid-Araya JM, Schmid PE (1995) Preliminary results on diet of stream invertebrate species: the meiofaunal assemblages. Jahresber Biol Stn Lunz 15:23–31

Schmid-Araya JM, Schmid PE (2000) Trophic relationships: integrating meiofauna into a realistic benthic food web. Freshw Biol 44:149–163. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2427.2000.00594.x

Schmid-Araya JM, Hildrew AG, Robertson A, Schmid PE, Winterbottom J (2002) The importance of meiofauna in food webs: evidence from an acid stream. Ecology 83:1271–1285. https://doi.org/10.1890/0012-9658(2002)083%5b1271:tiomif%5d2.0.co;2

Seinhorst JW (1959) A rapid method for the transfer of nematodes from fixative to anhydrous glycerin. Nematologica 4:67–69. https://doi.org/10.1163/187529259X00381

Seinhorst JW (1962) On the killing, fixation and transferring to glycerine of nematodes. Nematologica 8:29–32. https://doi.org/10.1163/187529262X00981

Shurin JB (2000) Dispersal limitation, invasion resistance, and the structure of pond zooplankton communities. Ecology 81:3074–3086. https://doi.org/10.1890/0012-9658(2000)081%5b3074:dlirat%5d2.0.co;2

Strommer JL, Smock LA (1989) Vertical distribution and abundance of invertebrates within the sandy substrate of a low-gradient headwater stream. Freshw Biol 22:263–274. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2427.1989.tb01099.x

Swan CM, Palmer MA (2000) What drives small-scale spatial patterns in lotic meiofauna communities? Freshw Biol 44:109–121. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2427.2000.00587.x

Tavares-Cromar AF, Williams DD (1997) Dietary overlap and coexistence of chironomid larvae in a detritus-based stream. Hydrobiologia 354:67–81. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1003011406218

ter Braak CJF (1994) Canonical community ordination. Part I: basic theory and linear methods. Ecoscience 1:127–140

Thomas MC, Lana PC (2011) A new look into the small-scale dispersal of free-living marine nematodes. Zoologia (Curitiba, Impr.) 28:449–456. https://doi.org/10.1590/s1984-46702011000400006

Tonkin JD, Altermatt F, Finn DS, Heino J, Olden JD, Pauls SU, Lytle DA (2018) The role of dispersal in river network metacommunities: patterns, processes, and pathways. Freshw Biol 63:141–163. https://doi.org/10.1111/fwb.13037

Tornero I, Boix D, Bagella S, Pinto-Cruz C, Caria MC, Belo A, Lumbreras A, Sala J, Compte J, Gascón S (2018) Dispersal mode and spatial extent influence distance-decay patterns in pond metacommunities. PLoS ONE 13:e0203119. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0203119

Traunspurger W (2000) The biology and ecology of lotic nematodes. Freshw Biol 44:29–45. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2427.2000.00585.x

Traunspurger W, Höss S, Witthöft-Mühlmann A, Wessels M, Güde H (2012) Meiobenthic community patterns of oligotrophic and deep Lake Constance in relation to water depth and nutrients. Fundam Appl Limnol 180:233–248. https://doi.org/10.1127/1863-9135/2012/0144

Traunspurger W, Threis I, Majdi N (2015) Vertical and temporal distribution of free-living nematodes dwelling in two sandy-bed streams fed by helocrene springs. Nematology 17:923–940. https://doi.org/10.1163/15685411-00002914

Ullberg J, Ólafsson E (2003) Free-living marine nematodes actively choose habitat when descending from the water column. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 260:141–149. https://doi.org/10.3354/meps260141

Urban MC, de Meester L (2009) Community monopolization: local adaptation enhances priority effects in an evolving metacommunity. Pro Biol Sci 276:4129–4138. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2009.1382

Usseglio-Polatera P, Bournaud M, Richoux P, Tachet H (2000) Biological and ecological traits of benthic freshwater macroinvertebrates: relationships and definition of groups with similar traits. Freshw Biol 43:175–205. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2427.2000.00535.x

Valls L, Castillo-Escrivà A, Mesquita-Joanes F, Armengol X (2016) Human-mediated dispersal of aquatic invertebrates with waterproof footwear. Ambio 45:99–109. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13280-015-0689-x

Vanschoenwinkel B, Gielen S, Seaman M, Brendonck L (2008) Any way the wind blows—frequent wind dispersal drives species sorting in ephemeral aquatic communities. Oikos 117:125–134. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2007.0030-1299.16349.x

Vinson MR, Hawkins CP (1998) Biodiversity of stream insects: variation at local, basin, and regional scales. Annu Rev Entomol 43:271–293. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.ento.43.1.271

Wallace JB, Webster JR, Meyer JL (1995) Influence of log additions on physical and biotic characteristics of a mountain stream. Can J Fish Aquat Sci 52:2120–2137. https://doi.org/10.1139/f95-805

Waterkeyn A, Pineau O, Grillas P, Brendonck L (2010) Invertebrate dispersal by aquatic mammals: a case study with nutria Myocastor coypus (Rodentia, Mammalia) in Southern France. Hydrobiologia 654:267–271. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10750-010-0388-3

Williams DD (1977) Movements of benthos during the recolonization of temporary streams. Oikos 29:306–312

Williams DD, Hynes HBN (1976) The recolonization mechanisms of stream benthos. Oikos 27:265–272

Winterbourn MJ, Crowe ALM (2001) Flight activity of insects along a mountain stream: is directional flight adaptive? Freshw Biol 46:1479–1489. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2427.2001.00766.x

Acknowledgements

Open Access funding provided by Projekt DEAL. We thank Stefanie Gehner for her help in preparing nematodes for identification, Viktoria Ronschke and Philip Wolf for their help in the field, and the German Federal Institute of Hydrology (BfG) for supporting our research. We also thank the anonymous reviewers for their helpful remarks that largely improved this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Handling Editor: Télesphore Sime-Ngando.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ptatscheck, C., Gansfort, B., Majdi, N. et al. The influence of environmental and spatial factors on benthic invertebrate metacommunities differing in size and dispersal mode. Aquat Ecol 54, 447–461 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10452-020-09752-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10452-020-09752-2