Abstract

The 2018 Anak Krakatoa volcano flank collapse generated a tsunami that impacted the Sunda Strait coastlines. In the absence of a tsunami early warning system, it caused several hundred fatalities. There are ongoing discussions to understand how the failure mechanism of this event affected landslide dynamics and tsunami generation. In this paper, the sensitivity to different failure scenarios on the tsunami generation is investigated through numerical modelling. To this end, the rate of mass release, the landslide volume, the material yield strength, and orientation of the landslide failure plane are varied to shed light on the failure mechanism, landslide evolution, and tsunami generation. We model the landslide dynamics using the depth-averaged viscoplastic flow model BingClaw, coupled with depth-averaged long wave and shallow water type models to simulated tsunami propagation. We are able to match fairly well the observed tsunami surface elevation amplitudes and inundation heights in selected area with the numerical simulations. However, as observed by other authors, discrepancies in simulated and observed arrival times for some of the offshore gauges are found, which raises questions related to the accuracy of the available bathymetry. For this purpose, further sensitivity studies changing the bathymetric depth near the source area are carried out. With this alteration we are also able to match better the arrival times of the waves.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Landslides and volcano flank collapse tsunamis arguably represent the second most important tsunami source with respect the hazard they pose to populations (Harbitz et al. 2014; Tappin 2010). From large sub-aqueous landslides, involving volumes of hundred to thousands \(\mathrm {km^3}\) (Masson et al. 2006), to smaller subaerial landslides impacting the water surface with large speed (Harbitz et al. 2014), landslides span very different scales and types of generation mechanisms (Heidarzadeh et al. 2014; Løvholt et al. 2015; Yavari-Ramshe and Ataie-Ashtiani 2016). Volcano flank collapses comprise one of the most important subset of tsunamigenic landslides, as recently demonstrated by the 2018 Anak Krakatoa tsunami (Babu and Kumar 2019; Gouhier and Paris 2019; Grilli et al. 2019; Walter et al. 2019; Muhari et al. 2019; Paris et al. 2020; Heidarzadeh et al. 2020; Novellino et al. 2020; Ye et al. 2020; Putra et al. 2020) and is the focus of this study. History has shown that Anak Krakatoa, by no means, represents a unique event.

In the seventeenth century, two devastating flank collapse tsunamis, in Shimabara 1792 (Sassa et al. 2016), and in Oshima-Oshima 1741 (Satake and Kato 2001; Satake 2007) impacted Japanese coastlines. Both caused several thousand fatalities, the 1792 Shimabara event being the most fatal of all historical landslide tsunamis. It has also been speculated that flank collapses were a major factor in generating the 1883 Krakatoa tsunami (Nomanbhoy and Satake 1995). Reviews of historical events in Indonesia (Løvholt et al. 2012; Paris et al. 2014) and the Caribbean (Harbitz et al. 2012) list several more instances of landslide tsunamis from volcanoes. In 2002, a smaller event emerged from the Stromboli volcano (Tinti et al. 2005). Consequently, a more widespread tsunami threat emerging from potentially much more voluminous flank collapses with oceanic propagation have been subject to speculation (Ward and Day 2001). To test this hypothesis, this had lead to development of models for dealing with both the near-field and far-field tsunami generation and propagation (Løvholt et al. 2008; Abadie et al. 2012). Subject to debate has been to which extent flank large collapses occur as single events, or with stage-wise release of the volume as evident from deposits of Canary Island events (Wynn et al. 2002; Masson et al. 2006; Paris et al. 2017). With the recent Anak Krakatoa event in mind, there is a timely need to better understand how this mechanism controls the tsunami generation.

1.1 The 2018 Anak Krakatoa Event

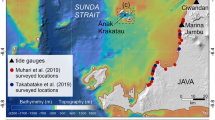

On 22 December 2018, the collapse of Anak Krakatoa produced a devasting tsunami that inundated southern Sumatra and western Java in Indonesia, and caused several hundred fatalities (Muhari et al. 2019; Putra et al. 2020). The tsunami hit the nearest coast \(35\,\mathrm {min}\) after the southwestern volcanic flank collapse of Anak Krakatoa. Four tidal gauges recorded the tsunami heights at the western Java coast, in Marina Jambu and Ciwandan, and at the southern Sumatra coast, in Panjang and Kota Agung (see Fig. 1). The maximum surface elevation of these four gauge stations was recorded in Marina Jambu with a height of \(1.40\,\mathrm {m}\). A post-tsunami field survey by Muhari et al. (2019) in two regions at the western Java coast found a maximum measured runup height above \(13\,\mathrm {m}\) in Pantai Legon Tanjungjaya, south of the western Java coast (see Fig. 1). Putra et al. (2020) reported a similar maximum runup height in the same region.

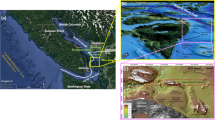

The Krakatoa complex, containing four islands, the Anak Krakatoa Volcano, Sertung Island, Panjang Island, and Rakata Island, is located in the centre of Sunda Strait, Indonesia. The three surrounding islands, together with the submarine caldera, are remnants of the 1883 Krakatoa eruption, which has been studied by several authors (Francis and Self 1983; Camus and Vincent 1983; Decker and Hadikusumo 1961; Sigurdsson et al. 1991; Deplus et al. 1995; Nomanbhoy and Satake 1995; Paris et al. 2014). Anak Krakatoa has frequently erupted since 1927, with eruptions typically strombolian to vulcanian in style, characterized by small explosive eruptions with columns reaching to \(1\,\mathrm {km}\) in height, pyroclastic and lava flows (Camus et al. 1987; Kimata et al. 2012; Suwarsono et al. 2019). During these eruptions in the last decades, Anak Krakatoa built up to a height of around \(330\,\mathrm {m}\) above sea level. Based on seismographs on the Sertung island and elsewhere on Sumatra and Java, Muhari et al. (2019) identified the 2018 Anak Krakatoa flank collapse to have taken place at 20:55 local time.

Giachetti et al. (2012) simulated a hypothetical Anak Krakatoa flank collapse already several years ago, and their scenario volume (\(0.28\,\mathrm {km}^3\)) and configuration was in fact very similar to the event that occurred in 2018, but their simulated waves were substantially larger. Grilli et al. (2019) modelled the 2018 Anak Krakatoa flank collapse as a deformable landslide on a geometrical failure plane interpreted from their satellite images. They applied three different volumes and two rheologies, one being a granular material and the other one being a dense viscous fluid. Moreover, Paris et al. (2020) used a Savage Hutter model to simulate the landslide dynamics and coupling to the tsunami generation. A sensitivity study on the landslide friction angle was carried out, and a reasonably good agreement with surface elevations observations at the four gauge stations were found. A moderate effect of frequency dispersion for the wave propagation was also reported. Heidarzadeh et al. (2020) studied a combination of numerical simulations with physical sliding experiments to propose an initial wave of the event. The influence of the geometry of the initial wave and related energy were tested. However, the degree of sensitivity studies in above studies were limited to study the variability to landslide volume and model rheologies (Grilli et al. 2019), to the friction angle (Paris et al. 2020), to the geometry of the initial wave (Heidarzadeh et al. 2020), and none of the above studies investigated the sensitivity to the rate of landslide mass release, bathymetric depth, failure orientation, or inundation, which are all subject to investigation here.

In this study, we treat the 2018 Anak Krakatoa flank collapse as a depth-averaged visco-plastic Herschel–Bulkley type flow with the landslide model BingClaw (Løvholt et al. 2017; Kim et al. 2019; Vanneste et al. 2019). BingClaw has previously been successfully used for modelling clay-rich materials of the largest submarine landslides of the world such as Trænadjupet and Storegga (Løvholt et al. 2017; Kim et al. 2019), and the 1929 Grand Banks landslide (Løvholt et al. 2018; Zengaffinen et al. 2020). Here we use BingClaw for modelling the volcanic rock–slope landslide failure dynamics. The reason why we choose to use BingClaw for this study is that it is the only model we are aware of that allows the failure mass to be released gradually over time, rather than as a single failure.

Topo-bathymetric map of the Sunda Strait including the southern coasts of the Sumatra Island and western coasts of the Java Island. The interval of isobaths is \(100\,\mathrm {m}\) below a water depth of \(100\,\mathrm {m}\) and \(25\,\mathrm {m}\) in shallower regions. The light blue labelled markers indicate the locations of the four tidal observation gauge stations and the green marker the location of the observation of the maximum runup height (\(13.5\,\mathrm {m}\)). The two reddish markers indicate the locations where dispersion and tsunami model tests are evaluated. The green rectangle in the middle of the map surrounds the Krakatoa complex, which is shown in more detail in Fig. 2. Two red rectangles at the coast of the Java Island define the regions for the inundation study. The violet zone extends over the region where the seafloor is deepened to give a minimum depth of \(60\,\mathrm {m}\)

1.2 Aims and Overview

The overarching aim of our study is to understand the mechanism of the landslide that caused the tsunami. In order to do so, we address the following questions.

-

1.

Was the landslide a single stage or a multistage event?

-

2.

How does the landslide directivity affect tsunami generation?

-

3.

How sensitive is the model to potential errors in the bathymetry?

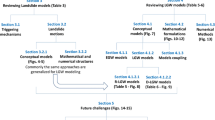

Section 2 presents the landslide and tsunami models, gives an overview of relevant input parameters and modelling setups, and describes the tidal gauge and runup height observations. In Sect. 3 we use a basic scenario to describe model tests, and to show contour plots of the landslide and tsunami. Then, through a parametric sensitivity analysis, we show the effect of the model parameters on the surface elevations at the four main gauge stations and compare the results to observations. For the basic scenario, which is the best fit scenario, an inundation study is compared to field observations. Section 4 summarises key conclusions.

2 Methods and Background

2.1 Landslide Model

In this paper, we use the viscoplastic landslide model BingClaw (Løvholt et al. 2017; Kim et al. 2019; Vanneste et al. 2019) to simulate the volcano flank collapse of the 2018 Anak Krakatoa event. The model implements the Herschel–Bulkley rheology in a two-layer depth-averaged formulation (Huang and Garcia 1998). Kim et al. (2019) presented a detailed description and derivation of the model. BingClaw solves the mass conservation equation integrated over the entire flow depth, the momentum conservation equation integrated separately over the plug layer depth and shear layer depth, in two horizontal dimensions (2HD). The model combines a finite volume method for the leading order terms with a finite difference method for the source terms, and employs the conservation law package ClawPack (Mandli et al. 2016) using the GeoClaw module (Berger et al. 2011). If the earth pressure \(p = \rho _d g' h \nabla (h+b)\) exceeds the shear strength of the material in a given computational cell, the dynamic equations are solved with a Godunov fractional step method. First, the equations without friction terms are solved, then the frictional terms. If the shear strength is larger than the earth pressure, no motion is imposed.

A notable aspect of the model is that it can simulate remoulding of landslide material, changes in material properties over time. The maximum yield strength of the material will be lowered to a residual yield strength as a function of accumulated shear deformation, which is described by the use of a heuristic formulation (De Blasio et al. 2005)

where \(\tau _{y_r}\) is the residual yield strength, \(\tau _{y_0}\) the maximum yield strength, \(\varGamma\) the remoulding rate, and \(\gamma\) the accumulated shear deformation.

In addition to remoulding of the yield strength over the entire landslide area, BingClaw allows the user to pre-remould parts of the landslide volume before the landslide motion is initiated. Here, we pre-remould a subset of the landslide volume extending some distance up from the slide toe. This feature allows the down-slope part to flow out first, which can help setting up landslide simulations that mimic a cascading failure.

2.2 Tsunami Models

We use two depth-averaged long wave models to simulate propagating tsunamis over varying bathymetry. The first model is GeoClaw that is used for the majority of the analyses. It assumes hydrostatic pressure, captures propagation of breaking waves, bottom drag, and dry-land inundation with a moving shoreline (LeVeque et al. 2011; Berger et al. 2011). GeoClaw incorporates the non-linear shallow water (NLSW) equations in conservative form and in 2HD, and uses the shock-capturing Finite Volume methods and Riemann solvers for ClawPack. Secondly, we use the GloBouss model, that is run with both linear shallow water (LSW) and linear dispersive (disp) equations in order to evaluate the importance of dispersion. GloBouss lacks features such as a moving shoreline. Hence, it cannot be used for simulating dry-land inundation (Pedersen 2008; Løvholt et al. 2008).

The temporal volumetric change of the bathymetry caused by the submarine mass movements are the primary sources for the tsunami generation. Such progressing changes in the bathymetry are output from BingClaw at given times and are used directly in the tsunami generation model. We use only GeoClaw as a tsunami generation model. GloBouss is merely used as a tsunami propagation model that takes the surface elevations and velocities from GeoClaw at \(600\,\mathrm {s}\) as initial conditions. At this time the landslide is nearly at rest and the leading waves have escaped the Krakatoa complex.

2.3 Model Setup

2.3.1 Geometrical and Geotechnical Input

We employ the default parameters listed in Table 1. Our landslide density \(\rho _d = 1500\,\mathrm {kg}\,\mathrm {m}^{-3}\) is based on the study of a potential Anak Krakatoa flank failure by Giachetti et al. (2012). The Herschel–Bulkely flow exponent n is \(0< n < 1\) for shear-thinning materials. During preliminary tests, it was found that n is not important for the tsunami generation (Zengaffinen et al. 2020). We employ \(n=0.5\). The reference strain rate \(\dot{\gamma }_r\) relates dynamic viscosity, yield strength and the Herschel–Bulkley flow exponent (Kim et al. 2019). We set \(\dot{\gamma }_r = 1.6 \cdot 10^{7} \,\mathrm {s}^{-1}\). The maximum yield strength \(\tau _{y_0}\) of the landslide material defines its strength at the initial time unless pre-remoulded. This strength is applied to the up-slope, initially stable, volume. We tested several \(\tau _{y_0}\) values to obtain \(\tau _{y_0} = 4 \,\mathrm {MPa}\) that can, in combination with the applied value ranges for the residual yield strength \(\tau _{y_r}\) (see Table 2) and remoulding rate \(\varGamma\), mimic a cascading failure. We tested several \(\varGamma\) values to ensure that the landslide can mobilise despite the relatively large initial yield strength. We use \(\varGamma = 0.9\) in this study. Laboratory experiments by Watts (2000) suggest an added-mass coefficient \(C_m\) in the order of magnitude of 1 for short blocks. However, \(C_m\) is also dependent on the ratio between landslide thickness and landslide length (Enet and Grilli 2007). \(C_m = 0.1\) is used herein. For the tsunami modelling, we use a sea water density \(\rho _w = 1000\,\mathrm {kg}\,\mathrm {m}^{-3}\) and a Manning coefficient \(M=0.025\) (Berger et al. 2011).

With these default paramteter values, we investigate the sensitivity to geometrical parameters such as the landslide directivity, the total and pre-remoulded release volume (see Table 2):

-

1.

Landslide directivity: A constantly inclined failure plane separates the viscoplastic landslide material from the stable volcano rocks, whose dip angle of \(8.2^{\circ }\) (Giachetti et al. 2012) defines the angle of the landslide entering the water. Satellite images indicate a south-west failure direction of the 2018 event, e.g. \(\theta = 135^{\circ }\) west from the north (Babu and Kumar 2019). In order to investigate a sensitivity to the dip direction, which controls the landslide directivity, we include also scenarios with failure plane dip directions of \(\theta = 125^{\circ }\) and \(\theta = 145^{\circ }\) (see Fig. 2).

-

2.

Total release volume: The height of the failure plane defines the total release volume, i.e. the entire viscoplastic material above the failure plane. Giachetti et al. (2012) used a total volume of \(0.28\,\mathrm {km}^3\) as a hypothesis for the 2018 Anak Krakatoa flank collapse. We employ this volume, as well as a smaller volume of \(0.21\,\mathrm {km}^3\), to model the sensitivity to the landslide volume. Our choice of landslide volumes is consistent with the volume range of 0.22–0.30 \(\,\mathrm {km}^3\) previously reported by Grilli et al. (2019), and 0.175–0.236 \(\,\mathrm {km}^3\) reported by Heidarzadeh et al. (2020) for the 2018 Anak Krakatau flank collapse.

-

3.

Pre-remoulded release volume: We split the total volume into a down-slope, initially weak, and an up-slope, initially stable, volume (see section above). The down-slope volume defines the pre-remoulded release volume that we alter from 1 to 60%, and finally 100% of the total release volume in order to indicate that a single collapse event triggered the tsunami. The volume will fail sequentially if the pre-remoulded release volume is less than 100%. Figure 3 illustrates three different values for a pre-remoulded release volume in a transect through the volcano.

Topo-bathymetric map of the Krakatoa complex including the volcano Anak Krakatoa and the three surrounding islands, Sertung, Panjang, and Rakata. The interval of isobaths is \(25\,\mathrm {m}\). The initial landslide volume is rendered in red with the periphery as a light green line. The three lines through the volcano indicate the various investigated failure plane dip directions, \(\theta = 125^{\circ }, 135^{\circ }, 145^{\circ }\). We show the transect corresponding to \(125^{\circ }\) (in yellow colour) in Fig. 3, and use the transect to extract results on the landslide evolution in Fig. 11 and extract refinement test results in Fig. 16. The violet zone extends over the region with a deepened seafloor

Transect through the volcano Anak Krakatoa at \(125^{\circ }\) from the north. The black line indicates the post-collapse sea bottom. The area between the green line and black line represents the viscoplastic material prior to failure. A pre-remoulded release volume of \(1\%\) of the total release volume comprises the area from the bottom of the volcano to the blue vertical line, and an pre-remoulded release volume of \(60\%\) to the red vertical line. The profile location is shown in Fig. 2

Apart from the geometrical parameters, we also investigate the sensitivity to the residual yield strength (see Table 2). The yield strength is remoulded to the residual yield strength over time for materials originating from the up-slope, initially stable, volume, as defined by Eq. 1. The down-slope, initially unstable, volume is pre-remoulded, meaning that the residual yield strength is applied at the initial time. In this study, we investigate the sensitivity to the remoulded yield strength for \(\tau _{y_r} = 1 \,\mathrm {kPa}\), \(100 \,\mathrm {kPa}\), which are reasonable values based on preliminary tests.

In addition to the model parameters for the sensitivity studies explained above, we test the effect of friction and pressure drag coefficients, \(C_F\) and \(C_P\), respectively, on the landslide velocities. We base our value ranges, \(C_F=0.001\), 0.0025, 0.005, 0.01 and \(C_P=0.1\), 0.5, 1.0, on the value ranges from studies by De Blasio et al. (2004) and Kim et al. (2019). It was found that for this particular setting, these different \(C_F\) and \(C_P\) values only gave differences between 4 to 5% on the maximum landslide velocities and with little influence on the tsunami generation, hence, they were not investigated further.

2.3.2 Applied Bathymetric Grids

Our analysis is based on the topo-bathymetric grid provided by Giachetti et al. (2012). They used data which are based on a combination of four digital elevation models, (I) ASTER topography with a \(30\,\mathrm {m}\)-resolution, (II) submarine bathymetric maps from the Indonesian navy, (III) GEBCO bathymetry with around \(900\,\mathrm {m}\)-resolution of the entire Sunda Strait region, and (IV) a bathymetric map of the Krakatoa Archipelago from Deplus et al. (1995). The merged topo-bathymetry has a resolution of \(100\,\mathrm {m}\) in both x- and y-direction in Cartesian coordinates (WGS 84). The topo-bathymetry from Giachetti et al. (2012) is constructed prior to the failure. In order to produce the topo-bathymetry for our failure area without the landslide material, we insert the \(8.2^{\circ }\)-inclined failure plane into the volcano at various heights and orientations, as mentioned above, and cut the material above the failure plane.

In the applied bathymetry, north of the volcano Anak Krakatoa, there is a shallow water basin that has a depth of approximately \(10\,\mathrm {m}\). Because the simulations are highly sensitive to the accuracy of the bathymetry, and we observe significant offsets between simulated and observed dominating wave periods and arrival times, we cannot rule out inaccuracies in the applied bathymetry. We remark that this mismatch was also observed by the simulations carried out by Grilli et al. (2019) and Paris et al. (2020). We also note that such errors in open source data previously have been shown to be significant for other areas in this region, such as Palu. Therefore, we deepen the seafloor to \(60\,\mathrm {m}\) over a total area of \(174\,\mathrm {km}^2\) reaching \(19\,\mathrm {km}\) in latitudinal direction (see Fig. 1) to remove the shallow region north of the volcano. We have no firm justification for this manipulation of the bathymetry, save that it turns out to improve the agreement between observations and simulations. It may also serve as an example of the effects of uncertain bathymetry. To avoid abrupt transitions in the depth, we increase the depth between two adjacent cells in the modified area by a maximum of \(3\,\mathrm {m}\). We use this modified data, as well as the original data from Giachetti et al. (2012), for a sensitivity to our pre-collapse bathymetry (see Table 2). For instance, a deeper bathymetry can lead to changes in earlier arrival times, and also makes the waves less prone to dissipation and breaking in the early phase of propagation.

The depth matrix for simulating the landslide dynamics covers the Krakatoa complex in a rectangle with length \(15\,\mathrm {km}\) in longitudinal and \(14.5\,\mathrm {km}\) in latitudinal directions, respectively. The applied grid resolution is \(36\,\mathrm {m}\) in both directions, which is interpolated from the original topo-bathymetric data with a resolution of \(100\,\mathrm {m}\) provided by Giachetti et al. (2012). The values of the grid cells adjacent to the boundary are copied into two ghost cells. This aids the implementation of non-reflecting outflow (LeVeque 2002). The depth matrix for the tsunami propagation computation covers the entire Sunda Strait region, including the Krakatoa complex, the western Java coast, and the southern Sumatra coast, forming a square of \(180\,\mathrm {km}\) side length. The resolution in GeoClaw is \(175\,\mathrm {m}\) in both directions, which is interpolated from the \(100\,\mathrm {m}\)-resolution topo-bathymetry, and the resolution in GloBouss is \(100\,\mathrm {m}\). We apply non-reflecting outflow boundaries to the grid used by GeoClaw. In GloBouss we apply a sponge layer with \(2.5\,\mathrm {km}\) at all boundaries, which relaxes the surface elevation (Pedersen and Løvholt 2008), and to avoid artificial coastal oscillations, we apply a minimum computation depth of \(1\,\mathrm {m}\). The accuracy using the different model resolutions for BingClaw, GeoClaw, and GloBouss through grid refinement tests is provided in the appendix.

We analyse two regions along the western Java coast for the tsunami inundation simulations with GeoClaw. The northern region, located east of Anak Krakatoa around the Marina Jambu gauge, is defined by a rectangle with length \(8.4\,\mathrm {km}\) in longitudinal and \(11.7\,\mathrm {km}\) in latitudinal directions, respectively. The southern region, located south-east of Anak Krakatoa around Pantai Legon Tanjungjaya, has an extent of \(7.0\,\mathrm {km}\) in longitudinal direction, and \(16.7\,\mathrm {km}\) in latitudinal direction (see Fig. 4). The grid resolution in both longitudinal and latitudinal directions is \(11\,\mathrm {m}\) for both regions, which is interpolated from the original topo-bathymetric grid with a \(100\,\mathrm {m}\)-resolution. As the topographic data is based on open source data, the accuracy of the inundation distances can be expected to be limited. Hence, we limit our inundation analysis to compare with observed heights.

2.4 Observations

Muhari et al. (2019) studied pre- and post-event bathymetric data in the caldera formed by the 1883 eruption. Their analysis showed more than \(50\,\mathrm {m}\) thick sediments in the 1883 caldera, which we use to validate our landslide model.

Observed tsunami surface elevation time series at the four different gauge stations, Kota Agung and Panjang at the southern coast of Sumatra, and Ciwandan and Marina Jambu at the eastern coast of Java (Muhari et al. 2019), serve as comparison to our simulated surface elevation time series. Each gauge station is equipped with three sensors. We set our initial sea level relative to Mean High Water (MHW). In Figs. 9, 10, 12, 13, and 14 we show detided surface elevation time series in Kota Agung, Panjang, and Ciwandan from sensor 2. All three sensors recorded very similar data. For Marina Jambu we show the detided data from sensor 1 and 3, because sensor 1 measured a leading crest twice as large as sensor 3, and sensor 2 did not work when the waves arrived. The sampling rate of the observed tidal data is once a minute, which is quite coarse given the 5–15 min observed first arrival wave periods (see Table 3).

Due to the coarse resolution of the shoreline in our bathymetry, we moved the gauges 300 m off the coasts. Taking into accounts the depths, that are in the range 1–6 m, say, this may shift arrival times about 100 s. This is of the same order as the deviations in arrival times that we encounter in the simulations, which illustrates the sensitivity of the arrival time to the details of the coastal bathymetry. We list measured first arrival times, surface elevations, and first wave periods of the tidal time series in Table 3. The first arrival time is defined by the time of the first sea-level rise with a threshold value of \(5\,\mathrm {cm}\) due to noise in the observed time series. The same extraction method is used for simulated wave metrics, but due to lower noise level, the threshold value is set to \(1\,\mathrm {cm}\). For the simulations the reduced threshold will make a significant difference only for the Panjang wave gauge. Here, the low \(1\,\mathrm {cm}\) threshold leads to inclusion of the low precursor in the simulations between 3800 and \(3960\,\mathrm {s}\), say. This low elevation presumably has taken a different path from the source than the following crest of \(0.41\,\mathrm {m}\) and is thus not included in the calculation of the period of the first simulated wave. While the low precursor reduces the difference in travel time between the simulation and the observation, it must be pointed out that the wave shapes are very different (see Figs. 9, 10, 12, 13, and 14). In addition, the observed time series are coarsely resolved. Hence, the interpretations of the arrival times are uncertain. The first wave period is defined by twice the time difference between the first zero-crossing and the first arrival time, except in Panjang (see above). In Figs. 9, 10, 12, 13, and 14 the time series in Ciwandan is shifted by \(204\,\mathrm {s}\) forward in time in order to visualise the relatively good waveform match with the simulations.

In addition, Muhari et al. (2019) executed a post-tsunami field survey from 26 to 30 December 2018, whose data we use to compare with our inundation simulations. They provided twelve locations with runup height measurements at the Java coast, seven in the northern region and five in the southern one. Runup heights are in the range from 7.1 to \(13.5\,\mathrm {m}\) in the southern region, and from 3.5 to \(5.0\,\mathrm {m}\) in the northern region. Also Putra et al. (2020) conducted a post-tsunami field survey eight days after the event. They reported a maximum runup height near the northern region of \(2.7\,\mathrm {m}\) based on one measurement, and runup heights in the range from 4 to \(13\,\mathrm {m}\) near the southern region based on twelve measurements. These results are similar to those of Muhari et al. (2019).

3 Results

3.1 Assessment of Dispersion Effects

A measure of the importance of dispersion is

which is a temporal variable for the evolution of dispersion effects (Glimsdal et al. 2013). Here, h is the characteristic water depth, L the propagation distance, and \(\lambda = c_0 \, T\) the wave length of the wave front in the source area with linear wave speed \(c_0\) and wave period T. We evaluate \(c_0\) and T in two gauges \(10\,\mathrm {km}\) southwest and east of the volcano, which results in \(\lambda _{1} = 5.16\,\mathrm {km}\) for the southwestern gauge and \(\lambda _2 = 4.31\,\mathrm {km}\) for the eastern gauge. We evaluate the importance of dispersion, first, for waves travelling from the southwestern gauge to Kota Agung, and second, for waves travelling from the eastern gauge to Ciwandan. Using an average characteristic water depth \(h_1 = 320\,\mathrm {m}\), propagation distance \(L_1 = 90\,\mathrm {km}\), and \(\lambda _{1} = 5.16\,\mathrm {km}\), we get \(\tau _1 = 0.402\) for the waves in Kota Agung, which implies a significant dispersion effect. The reason for this significant effect is mostly due to the relatively deep basin between the source and Kota Agung. As a consequence, our results for this gauge give only an indication as we do not include dispersion for the GeoClaw simulations. On the other hand, using \(h_2 = 80\,\mathrm {m}\), \(L_2 = 45\,\mathrm {km}\), and \(\lambda _{2} = 4.31\,\mathrm {km}\), the dispersion effect is small, \(\tau _2 = 0.0216\), for waves in Ciwandan. A similar \(\tau\) implies for the gauges in Marina Jambu and Panjang, thus dispersion effects are small in these shallow parts in the Sunda Strait.

We run GloBouss from \(600\,\mathrm {s}\) after the flank failure (see Sect. 2.2) with both LSW and dispersive equations. Two gauges that are both positioned two thirds of the distance from the volcano to Kota Agung and to Ciwandan (see Fig. 1), are used to investigate the importance of dispersion. Concerning the leading crest, the difference between the dispersive equations and the LSW equations is \(2\%\) and \(5\%\), respectively, for the two gauges. For the later parts of the wave trains, the deviations are larger, in particular for the wave gauge on the way to Kota Agung (see Fig. 5). To compare the sensitivity due to the choice of model, we also compare the LSW version of GloBouss with GeoClaw at the same wave gauges. Here, the leading crest deviates by 7% between the two models, whereas later waves deviate to a larger extent (see Fig. 5), which may be due to artificial coastal reflections in the GloBouss model.

Simulated surface elevations at the two off-shore gauges (see Fig. 1) using different tsunami models. LSW stands for linear shallow water equations and disp for linear dispersive equations in GloBouss. Dispersive effects are more important at the deeper gauge, and the solution in GeoClaw and GloBouss disp match better at the deeper gauge

GloBouss results indicate that dispersive effects are small in shallow parts of the Sunda Strait, which is north, east, and south of Anak Krakatoa, and that a non-dispersive tsunami model is applicable. Heidarzadeh et al. (2020) reported a \(\tau\) in the same order of magnitude, and concluded that the effect of dispersion in the Sunda Strait is weak. On the other hand, Paris et al. (2020) found a larger influence of dispersion. However, their source model was quite different from the one used herein, and they also studied propagation in the deeper regions outside the Sunda Strait.

3.2 Landslide and Wave Propagation of the Basic Scenario

Figure 6 shows contour plots of the landslide masses prior to the release, \(15\,\mathrm {s}\), \(30\,\mathrm {s}\), and \(90\,\mathrm {s}\) after the release. The landslide mass starts flowing radially over the volcano with a maximum speed of \(35\,\mathrm {m}\,\mathrm {s}^{-1}\) towards southwest (see Fig. 7). When the material arrives in the submarine caldera, \(30\,\mathrm {s}\) after initiation, the landslide is guided by the shape of the caldera. After \(600\,\mathrm {s}\), the mean landslide speed is reduced to \(2\,\mathrm {m}\,\mathrm {s}^{-1}\), and after \(780\,\mathrm {s}\) the landslide stops moving and exhibiting a maximum deposit of ca. \(50\,\mathrm {m}\) (not shown here). The sediment thickness is similar to the findings from Muhari et al. (2019). Figure 8 shows six colour plots of the tsunami surface elevations after \(30\,\mathrm {s}\), \(60\,\mathrm {s}\), \(90\,\mathrm {s}\), \(120\,\mathrm {s}\), \(600\,\mathrm {s}\), \(1500\,\mathrm {s}\) after the landslide mass release. The waves start propagating radially inside the Krakatoa complex with a main propagation direction towards southwest. After \(120\,\mathrm {s}\) the waves escape the Krakatoa complex through three openings between the three surrounding islands of Anak Krakatoa.

Sensitivity to the remoulded yield strength for maximum and mean landslide velocities. Parameters held constant are listed in bold in Table 2

3.3 Parametric Sensitivity Study

We compare surface elevation time series for different values of the total release volume \(V_{tot}\), pre-remoulded release volume \(V_r\), landslide directivity \(\theta\), residual yield strength \(\tau _{y_r}\), and the bathymetry north of the volcano \(h_b\). The values of these parameters are presented in Table 2. One parameter is altered at a time, whereas the bold values from Table 2, which refers to the basic scenario, are used as default values. Also wave periods and arrival times are compared (see Table 3).

3.3.1 Total Release Volume

First, we show the sensitivity to the total release volume \(V_{tot}\) to the tsunami surface elevation time series in Fig. 9 for an instantaneous collapse. No remoulding is applied here, meaning that the yield strength, \(\tau _{y_r} = 1\,\mathrm {kPa}\), is constant for all times and the entire collapse volume. For all four gauges, the higher volume, \(V_{tot} = 0.28\,\mathrm {km}^3\), causes higher surface elevations than the lower volume, \(V_{tot} = 0.21\,\mathrm {km}^3\). For instance, in Panjang and Kota Agung, the leading crests for the larger landslide volume are about 1.5 times higher, respectively.

Sensitivity to the total release volume. The observed time series in Ciwandan is shifted by \(204\,\mathrm {s}\) forward in time in order to visualise the relatively good waveform match. Black lines are observations from sensor 2 for the gauges except in Marina Jambu, where the black lines is the observation from sensor 3 and the gray line from sensor 1. Parameters held constant are listed in bold in Table 2

3.3.2 Residual Yield Strength

The next parameter we investigate is the residual yield strength \(\tau _{y_r}\) for the instantaneous collapse with \(V_{tot} = 0.28\,\mathrm {km}^3\). The strength for the entire collapse volume is \(\tau _{y_r}\). Figure 7 shows the time evolution of the maximum and mean landslide velocities for both \(\tau _{y_r}\). Velocities for \(\tau _{y_r} = 1\,\mathrm {kPa}\) are larger and the landslide motion lasts longer than for \(\tau _{y_r} = 100\,\mathrm {kPa}\). The influence of \(\tau _{y_r}\) on the surface elevation time series at the four gauges is shown in Fig. 10. The time series for a yield strength \(\tau _{y_r} = 100\,\mathrm {kPa}\) show general lower surface elevations in all four gauges than for \(\tau _{y_r} = 1\,\mathrm {kPa}\). Overall, the smaller \(\tau _{y_r}\) provides better agreement with the observations, but not consistently.

Sensitivity to the remoulded yield strength. The observed time series in Ciwandan is shifted by \(204\,\mathrm {s}\) forward in time in order to visualise the relatively good waveform match. Black lines are observations from sensor 2 for the gauges except in Marina Jambu, where the black lines is the observation from sensor 3 and the gray line from sensor 1. Parameters held constant are listed in bold in Table 2

3.3.3 Gradual Mass Release

The scenarios above had a pre-remoulded volume \(V_r = V_{tot}\), which refers to an instantaneous collapse without remoulding. We vary the pre-remoulded release volume \(V_r < V_{tot}\) (see Sect. 2.3) to simulate a gradual mass release (see Fig. 12). The down-slope volume that is pre-remoulded fails first, and the up-slope, initially stable, volume is being remoulded during the landslide flow (see Fig. 11). The surface elevation time series of a gradual mass release over \(240\,\mathrm {s}\) for \(V_r = 0.6 \, V_{tot}\) has same wave periods and first arrivals as the instantaneous collapse, but in general lower surface elevations, except for the Kota Agung gauge.

Landslide evolution for various pre-remoulded release volumes in a transect \(15\,\mathrm {s}\) and \(60\,\mathrm {s}\) after failure. The transect is oriented \(125^\circ\) west from the north and is shown in Fig. 2

A pre-remoulded release volume of only \(V_r = 0.01 \, V_{tot}\) causes lower wave heights, later arrival times, and longer periods for all four gauges. The first arrival wave in Kota Agung has half the surface elevation and arrives \(400\,\mathrm {s}\) later than the waves caused by the instantaneous collapse. In Ciwandan and Marina Jambu the first arrival waves are troughs rather than crests, and reach the gauges around \(550\,\mathrm {s}\) later than the waves caused by the instantaneous collapse. In Panjang surface elevations are less than \(0.02\,\mathrm {m}\), whereas they reach up to \(0.4\,\mathrm {m}\) for the instantaneous collapse (\(V_r = V_{tot}\)). These differences imply that the gradual mass release has a major on the tsunami generation for such a setting.

In total, the instantaneous collapse yields somewhat better agreements with the observations than \(V_r = 0.6 \, V_{tot}\). Grilli et al. (2019), Paris et al. (2020), and Heidarzadeh et al. (2020) all based their simulations on an instantaneous collapse, which seems reasonable based on the results of our study. The very small \(V_r\) in our study is definitely off the mark.

Sensitivity to the pre-remoulded release volume. The observed time series in Ciwandan is shifted by \(204\,\mathrm {s}\) forward in time in order to visualise the relatively good waveform match. Black lines are observations from sensor 2 for the gauges except in Marina Jambu, where the black lines is the observation from sensor 3 and the gray line from sensor 1. Parameters held constant are listed in bold in Table 2

3.3.4 Landslide Directivity

We turn our attention back to an instantaneous mass release and focus on the landslide directivity \(\theta\) (measured counter-clockwise from the north). Figure 13 shows the sensitivity to \(\theta\) on the surface elevation time series. \(\theta = 145^{\circ }\) gives too high first waves in Ciwandan and Marina Jambu, and a too low first wave in Panjang, while there are only moderate differences between \(\theta = 125^{\circ }\) and \(\theta = 135^{\circ }\). The first wave in Kota Agung is hardly affected by \(\theta\). Later arrivals do not depend on \(\theta\) in a systematic manner for any gauges.

Sensitivity to landslide directivity. The observed time series in Ciwandan is shifted by \(204\,\mathrm {s}\) forward in time in order to visualise the relatively good waveform match. Black lines are observations from sensor 2 for the gauges except in Marina Jambu, where the black lines is the observation from sensor 3 and the gray line from sensor 1. Parameters held constant are listed in bold in Table 2

3.3.5 Modification of Bathymetric Depth

As a last test we investigate the water depth north of the landslide source (see Fig. 14) by applying an instantaneous volcano flank collapse. In the original bathymetry there is a shallow region with a minimum depth of \(h_b = 10\,\mathrm {m}\) north of the volcano (see Fig. 1). For our analysis, we increased the water depth in this region to obtain \(h_b = 60\,\mathrm {m}\), which was applied in all scenarios in Figs. 9, 10, 11, 12, 13. A variation in \(h_b\) has influence on the first arrivals in Panjang, whereas the first arrivals in the other three gauges are not sensitive to the change in bathymetry north of the volcano. In Panjang, the leading crest is 25% lower for \(h_b = 10\,\mathrm {m}\) than for \(h_b = 60\,\mathrm {m}\), and the arrival time of the first steep wave front is around \(100\,\mathrm {s}\) later for the lower \(h_b\). Subsequent crests differ in all gauges for varying \(h_b\).

Waves travel faster through the modified bathymetric area north of the volcano than through the shallower original bathymetry, which implicates an earlier first wave arrival in Panjang. Our simulated first arrival time in the Panjang gauge matches the observation better than with the original bathymetry. Moreover, waves travelling through the shallow region north of the volcano in the unmodified bathymetry are strongly steepening in the front. Analyses show that the first wave period increases with travel distance for the original bathymetry, while the first wave period is less subject to change when using the modified bathymetry. However, the simulated wave period in Panjang is still somewhat larger than the observed wave period. Also, the modified bathymetry leads to different interference patterns, which affects the waves at the Panjang gauge. Our simulated maximum surface elevation matches the observation better with the modified bathymetry (see Table 3).

We find similar discrepancies in the Kota Agung gauge where our simulated first arrival wave period is larger and the leading crest smaller than the observation (see Table 3). In addition to the small discrepancies due to the significance of dispersion (see Fig. 5), we assume inaccuracies of the bathymetry in general based on the surface elevation time series mismatch between observation and simulation at the coast of Sumatra. The coarse resolution and noisy appearance of the recordings may suggest that the recordings at the coast of Sumatra are inaccurate. The lack of the complex geometries of the harbours around the gauge stations in the applied topo-bathymetry presumably leads to mismatches (Grilli et al. 2019).

Sensitivity to the bathymetry north of the volcano. The observed time series in Ciwandan is shifted by \(204\,\mathrm {s}\) forward in time in order to visualise the relatively good waveform match. Black lines are observations from sensor 2 for the gauges except in Marina Jambu, where the black lines is the observation from sensor 3 and the gray line from sensor 1. Parameters held constant are listed in bold in Table 2

3.4 Analysis of Best Fit Scenario

An instantaneous volcanic flank collapse with a pre-remoulded and total release volume of \(V_r = V_{tot} = 0.28\,\mathrm {km}^3\) (similar to the one used by Grilli et al. 2019), a landslide directivity of \(\theta = 125^{\circ }\) west from the north (similar to the one used by Grilli et al. 2019; Heidarzadeh et al. 2020), a residual yield strength of \(\tau _{y_r} = 1\,\mathrm {kPa}\), and a modified water depth north of the volcano of \(h_b = 60\,\mathrm {m}\) produces a tsunami that matches the observed surface elevation time series at the four gauge stations best. This is the basic scenario and is regarded as best in respect of a visual comparison of wave arrival time, wave period, and surface elevation between observation and simulation. We compare our simulated wave metrics at the four gauge stations with observations (see Table 3).

-

1.

Maximum surface elevations: Our simulation matches the observed height of the leading crests in three of the four gauge stations, but underestimates the height in Kota Agung by a factor of two. Later crest heights in Ciwandan and Marina Jambu match the observations as well.

-

2.

Leading crest wave periods: Simulated first arrival wave periods are in the same range as the observed periods at the eastern coast of Java, in Ciwandan and Marina Jambu. The simulated wave periods in Kota Agung and Panjang are significantly larger than the observations.

-

3.

First arrival times: We adjusted the flank collapse time by requiring a correct arrival time for the Marina Jambu gauge and obtained 20:54:20. For comparison, Grilli et al. (2019) used an estimated local collapse time of 20:57 based on their simulations, whereas Muhari et al. (2019) identified the time of origin of tsunamigenic activity as 20:55 local time. The first arrival time agrees well in Kota Agung, but is \(204\,\mathrm {s}\) larger than the observed time in Ciwandan. Observations in Ciwandan are time-shifted in Figs. 9, 10, 11, 12, 13 to show a relatively good waveform match. The leading crest in Panjang arrives \(210\,\mathrm {s}\) later than the observation.

3.5 Inundation Study

The best fit scenario is used for an inundation study for the two selected regions at the Java coast described above (see Fig. 4). As stated above, the topographic data used to create the grid for the inundation analysis are based on open source information. As reported elsewhere (Griffin et al. 2015), such data can often lead to hindering the onshore flow and hence limit the horizontal inundation. Hence, we do not show inundation distances. Moreover, we remark that our ability to model local inundation effects are more limited than if high resolution data were available.

The maximum simulated runup height in the northern region is \(6.1\,\mathrm {m}\), and \(7.9\,\mathrm {m}\) in the southern region (see Fig. 15). In the northern region, the simulations agree well with the observations. Yet, for the three northernmost positions, the observed runup heights are underestimated by the simulations. However, the maximum simulated surface elevation in the Marina Jambu gauge is \(1.4\,\mathrm {m}\), which is the same as the maximum observed surface elevation. In the southern region runup heights are underestimated at all locations, except one. Here, we lack offshore tsunami data.

4 Concluding Remarks

We used the depth-averaged viscoplastic numerical landslide model BingClaw to simulate the 2018 Anak Krakatoa volcanic flank collapse, and coupled it to the non-linear numerical model GeoClaw that simulates the generation, propagation, and inundation of the resulting water waves. We showed that the flank collapse most likely took place as an instantaneous collapse rather than a gradual flank failure moving up-slope. For the instantaneous collapse, our simulations show a good overall match with observed wave periods, surface elevations, and arrival times at the two gauge stations on Java. On Sumatra, the simulations compare less well, and surface elevations are matched with our modified topo-bathymetric data at one gauge, and the first arrival time is matched at the other gauge. The landslide directivity is a significant control on surface elevation time series, which can be seen in three of the four gauge stations. Our best match is \(125^{\circ }\) west from the north. At the locations where we extracted runup heights from the inundation study, half the simulated data matches observed data, and the other half underestimates the observation.

Shallow waters dominate the northern and eastern Sunda Strait, which makes the tsunami modelling, based on open source data, sensitive to bathymetric errors as recently observed for the tsunami in Palu Bay. According to our analysis, the first arrival time in Panjang is matched better with the modification of the bathymetry, making it deeper north of the volcano, than with the original bathymetry. However, our simulated wave periods in Panjang are still three times as large as the observed wave periods. A possible reason for the large wave periods in the model, is due to artificially high dissipation and breaking in shallow regions. This may again be due to errors in the bathymetry, but this is difficult to verify without better bathymetric data.

We acknowledge that the simulations contain many uncertainties concerning the simplified failure plane, the estimation of the total collapse volume, the depth-averaging of the slide motion, the coarse topo-bathymetric data, and the fact that we modelled a dacite rock debris flow with a model previously used for clay-rich sediments. The post-collapse topo-bathymetric data, which has recently been acquired, will serve as a base for more accurate volume estimates, a more detailed failure surface, and an extent of the landslide run-out, which can be used to validate the landslide model. That will, next to our fairly well suited model, give a more consistent description of the 2018 Anak Krakatoa volcanic collapse and tsunami.

References

Abadie, S., Harris, J., Grilli, S., & Fabre, R. (2012). Numerical modeling of tsunami waves generated by the ank collapse of the Cumbre Vieja Volcano (La Palma, Canary Islands): Tsunami source and near field effects. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans, 117(C5).

Babu, A., & Kumar, S. (2019). InSAR Coherence and Backscatter Images Based Analysis for the Anak Krakatau Volcano Eruption. In Multidisciplinary digital publishing institute proceedings (Vol. 24, p. 21).

Berger, M. J., George, D. L., LeVeque, R. J., & Mandli, K. T. (2011). The GeoClaw software for depth-averaged flows with adaptive refinement. Advances in Water Resources, 34(9), 1195–1206. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.advwatres.2011.02.016.

Camus, G., Gourgaud, A., & Vincent, P. (1987). Petrologic evolution of Krakatau (Indonesia): Implications for a future activity. Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research, 33(4), 299–316. https://doi.org/10.1016/0377-0273(87)90020-5.

Camus, G., & Vincent, P. M. (1983). Discussion of a new hypothesis for the Krakatau volcanic eruption in 1883. Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research, 19, 167–173. https://doi.org/10.1016/0377-0273(83)90130-0.

De Blasio, F. V., Elverhøi, A., Issler, D., Harbitz, C. B., Bryn, P., & Lien, R. (2005). On the dynamics of subaqueous clay rich gravity mass flows—the giant Storegga slide, Norway. In Ormen Lange – an Integrated Study for Safe Field Development in the Storegga Submarine Area (pp. 179–186). Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-08-044694-3.50019-6.

De Blasio, F. V., Engvik, L., Harbitz, C. B., & Elverhøi, A. (2004). Hydroplaning and submarine debris flows. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans, 109(C1).

Decker, R. W., & Hadikusumo, D. (1961). Results of the 1960 expedition to Krakatau. Journal of Geophysical Research, 66(10), 3497–3511. https://doi.org/10.1029/JZ066i010p03497.

Deplus, C., Bonvalot, S., Dahrin, D., Diament, M., Harjono, H., & Dubois, J. (1995). Inner structure of the Krakatau volcanic complex (Indonesia) from gravity and bathymetry data. Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research, 64(1–2), 23–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/0377-0273(94)00038-I.

Enet, F., & Grilli, S. T. (2007). Experimental study of tsunami generation by three-dimensional rigid underwater landslides. Journal of Waterway, Port, Coastal, and Ocean Engineering, 133(6), 442–454. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)0733-950X(2007)133:6(442).

Francis, P., & Self, S. (1983). The eruption of Krakatau. Scientific American, 249(5), 172–187. https://doi.org/10.2307/24969038.

Giachetti, T., Paris, R., Kelfoun, K., & Ontowirjo, B. (2012). Tsunami haz665 ard related to a flank collapse of Anak Krakatau volcano, Sunda Strait, Indonesia. Geological Society, London, Special Publications, 361(1), 79–90. https://doi.org/10.1144/SP361.7.

Glimsdal, S., Pedersen, G. K., Harbitz, C. B., & Løvholt, F. (2013). Dispersion of tsunamis: Does it really matter? Natural Hazards and Earth System Sciences, 13(6), 1507–1526. https://doi.org/10.5194/nhess-13-1507-2013.

Gouhier, M., & Paris, R. (2019). So2 and tephra emissions during the december 22, 2018 anak krakatau eruption. Volcanica, 2(2), 91–103. 10.30909/vol.02.02.91103.

Griffin, J., Latief, H., Kongko, W., Harig, S., Horspool, N., Hanung, R., et al. (2015). An evaluation of onshore digital elevation models for modeling tsunami inundation zones. Frontiers in Earth Science, 3, 32. https://doi.org/10.3389/feart.2015.00032.

Grilli, S. T., Tappin, D. R., Carey, S., Watt, S. F., Ward, S. N., Grilli, A. R., et al. (2019). Modelling of the tsunami from the december 22, 2018 lateral collapse of anak krakatau volcano in the sunda straits, indonesia. Scientific Reports, 9(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-48327-6.

Harbitz, C. B., Glimsdal, S., Bazin, S., Zamora, N., Løvholt, F., Bungum, H., et al. (2012). Tsunami hazard in the Caribbean: Regional exposure derived from credible worst case scenarios. Continental Shelf Research, 38, 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.csr.2012.02.006.

Harbitz, C. B., Glimsdal, S., Løvholt, F., Kveldsvik, V., Pedersen, G. K., & Jensen, A. (2014). Rockslide tsunamis in complex fjords: From an unstable rock slope at Åkerneset to tsunami risk in western Norway. Coastal Engineering, 88, 101–122. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coastaleng.2014.02.003.

Harbitz, C. B., Løvholt, F., & Bungum, H. (2014). Submarine landslide tsunamis: How extreme and how likely? Natural Hazards, 72(3), 1341–1374. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11069-013-0681-3.

Heidarzadeh, M., Ishibe, T., Sandanbata, O., Muhari, A., & Wijanarto, A. B. (2020). Numerical modeling of the subaerial landslide source of the 22 December 2018 Anak Krakatoa volcanic tsunami, Indonesia. Ocean Engineering, 195, 106733. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oceaneng.2019.106733.

Heidarzadeh, M., Krastel, S., & Yalciner, A. C. (2014). The state-of-the-art numerical tools for modeling landslide tsunamis: A short review. In Submarine mass movements and their consequences (Vol. 37, pp. 483–495). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-00972-8_43

Huang, X., & Garcia, M. H. (1998). A Herschel-Bulkley model for mud flow down a slope. Journal of Fluid Mechanics, 374, 305–333. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022112098002845.

Kim, J., Løvholt, F., Issler, D., & Forsberg, C. F. (2019). Landslide material control on tsunami genesisthe storegga slide and tsunami (8,100 Years BP). Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans, 124(6), 3607–3627. https://doi.org/10.1029/2018JC014893.

Kimata, F., Pamitro, Y. E., Abidin, H. Z., et al. (2012). Understanding the 2007–2008 eruption of Anak Krakatau Volcano by combining remote sensing technique and seismic data. International Journal of Applied Earth Observation and Geoinformation, 14(1), 73–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jag.2011.08.011.

LeVeque, R. J. (2002). Finite volume methods for hyperbolic problems (Vol. 31). Cambridge: Cambridge university press.

LeVeque, R. J., George, D. L., & Berger, M. J. (2011). Tsunami modelling with adaptively refined finite volume methods. Acta Numerica, 20, 211–289. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0962492911000043.

Løvholt, F., Bondevik, S., Laberg, J. S., Kim, J., & Boylan, N. (2017). Some giant submarine landslides do not produce large tsunamis. Geophysical Research Letters, 44(16), 8463–8472. https://doi.org/10.1002/2017GL074062.

Løvholt, F., Kühn, D., Bungum, H., Harbitz, C. B., & Glimsdal, S. (2012). Historical tsunamis and present tsunami hazard in eastern indonesia and the southern philippines. Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth, 117(B9).

Løvholt, F., Pedersen, G., & Gisler, G. (2008). Oceanic propagation of a potential tsunami from the La Palma Island. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans, 113(C9).

Løvholt, F., Pedersen, G., Harbitz, C. B., Glimsdal, S., & Kim, J. (2015). On the characteristics of landslide tsunamis. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences, 373(2053), 20140376. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsta.2014.0376.

Løvholt, F., Schulten, I., Mosher, D., Harbitz, C. B., & Krastel, S. (2018). Modelling the 1929 Grand Banks slump and landslide tsunami. Geological Society, London, Special Publications, 477, 315–331. https://doi.org/10.1144/SP477.28.

Mandli, K. T., Ahmadia, A. J., Berger, M., Calhoun, D., George, D. L., Hadjimichael, Y., et al. (2016). Clawpack: Building an open source ecosystem for solving hyperbolic PDEs. PeerJ Computer Science, 2, e68. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj-cs.68.

Masson, D. G., Harbitz, C. B., Wynn, R. B., Pedersen, G. K., & Løvholt, F. (2006). Submarine landslides: Processes, triggers and hazard prediction. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences, 364(1845), 2009–2039. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsta.2006.1810.

Muhari, A., Heidarzadeh, M., Susmoro, H., Nugroho, H. D., Kriswati, E., Wijanarto, A. B., et al. (2019). The December 2018 Anak Krakatau Volcano tsunami as inferred from post-tsunami field surveys and spectral analysis. Pure and Applied Geophysics, 176(12), 5219–5233. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00024-019-02358-2.

Nomanbhoy, N., & Satake, K. (1995). Generation mechanism of tsunamis from the 1883 Krakatau eruption. Geophysical Research Letters, 22(4), 509–512. https://doi.org/10.1029/94GL03219.

Novellino, A., Engwell, S. L., Grebby, S., Day, S., Cassidy, M., Madden-Nadeau, A., et al. (2020). Mapping recent shoreline changes spanning the lateral collapse of anak krakatau volcano, indonesia. Applied Sciences, 10(2), 536. https://doi.org/10.3390/app10020536.

Paris, A., Heinrich, P., Paris, R., & Abadie, S. (2020). The December 22, 2018 Anak Krakatau, Indonesia, Landslide and Tsunami: Preliminary Modeling Results. Pure and Applied Geophysics, 177, 571–590. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00024-019-02394-y.

Paris, R., Bravo, J. J. C., González, M. E. M., Kelfoun, K., & Nauret, F. (2017). Explosive eruption, flank collapse and megat sunami at Tenerife ca. 170 ka. Nature Communications, 8, 15246. 10.1038/ncomms15246.

Paris, R., Switzer, A. D., Belousova, M., Belousov, A., Ontowirjo, B., Whelley, P. L., et al. (2014). Volcanic tsunami: a review of source mechanisms, past events and hazards in Southeast Asia (Indonesia, Philippines, Papua New Guinea). Natural Hazards, 70, 447–470. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11069-013-0822-8.

Paris, R., Wassmer, P., Lavigne, F., Belousov, A., Belousova, M., Iskandarsyah, Y., et al. (2014). Coupling eruption and tsunami records: the Krakatau 1883 case study. Indonesia Bulletin of Volcanology, 76(4), 814. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00445-014-0814-x.

Pedersen, G. (2008). Modeling runup with depth integrated equation models. In Advanced numerical models for simulating tsunami waves and runup (pp. 3–41). World Scientific. https://doi.org/10.1142/9789812790910_0001.

Pedersen, G., & Løvholt, F. (2008). Documentation of a global Boussinesq solver. Preprint series. Mechanics and Applied Mathematics http://urn. nb. no/URN: NBN: no-23418.

Putra, P. S., Aswan, A., Maryunani, K. A., Yulianto, E., Nugroho, S. H., & Setiawan, V. (2020). Post-Event Field Survey of the 22 December 2018 Anak Krakatau Tsunami. Pure and Applied Geophysics, 1–16, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00024-020-02446-8.

Sassa, K., Dang, K., Yanagisawa, H., & He, B. (2016). A new landslide induced tsunami simulation model and its application to the 1792 Unzen-Mayuyama landslide-and-tsunami disaster. Landslides, 13(6), 1405–1419. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10346-016-0691-9.

Satake, K. (2007). Volcanic origin of the 1741 Oshima–Oshima tsunami in the Japan Sea. Earth, Planets and Space, 59(5), 381–390. https://doi.org/10.1186/BF03352698.

Satake, K., & Kato, Y. (2001). The 1741 Oshima-Oshima eruption: Extent and volume of submarine debris avalanche. Geophysical Research Letters, 28(3), 427–430. https://doi.org/10.1029/2000GL012175.

Sigurdsson, H., Carey, S., Mandeville, C., & Bronto, S. (1991). Pyroclastic flows of the 1883 Krakatau eruption. Eos, Transactions American Geophysical Union, 72(36), 377–381. https://doi.org/10.1029/90EO00286.

Suwarsono, N., Prasasti, I., Nugroho, J. T., Sitorus, J., & Triyono, D. (2019). Detecting the lava ow depositis from 2018 Anak Krakatau eruption using data fusion landsat-8 opitc and sentinel-1 sar. International Journal of Remote Sensing and Earth Sciences, 15(2), 157–166. 10.30536/j.ijreses.2018.v15.a3078.

Tappin, D. R. (2010). Mass transport events and their tsunami hazard. In Submarine mass movements and their consequences (Vol. 28, pp. 667–684). Springer, Dordrecht. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-90-481-3071-9_54.

Tinti, S., Manucci, A., Pagnoni, G., Armigliato, A., & Zaniboni, F. (2005). The 30 December 2002 landslide-induced tsunamis in Stromboli: Sequence of the events reconstructed from the eyewitness accounts. Natural Hazards and Earth System Sciences, 5(6), 763–775.

Vanneste, M., Løvholt, F., Issler, D., Liu, Z., Boylan, N., Kim, J., et al. (2019). A Novel Quasi-3D Landslide Dynamics Model: From Theory to Applications and Risk Assessment. In Offshore Technology Conference.

Walter, T. R., Haghighi, M. H., Schneider, F. M., Coppola, D., Motagh, M., Saul, J., et al. (2019). Complex hazard cascade culminating in the anak krakatau sector collapse. Nature communications, 10(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-12284-5.

Ward, S. N., & Day, S. (2001). Cumbre Vieja volcano—potential collapse and tsunami at La Palma. Canary Islands. Geophysical Research Letters, 28(17), 3397–3400. https://doi.org/10.1029/2001GL013110.

Watts, P. (2000). Tsunami features of solid block underwater landslides. Journal of Waterway, Port, Coastal, and Ocean Engineering, 126(3), 144–152. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)0733-950X(2000)126:3(144).

Wynn, R. B., Weaver, P. P., Masson, D. G., & Stow, D. A. (2002). Turbidite depositional architecture across three interconnected deep-water basins on the north-west african margin. Sedimentology, 49(4), 669–695. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-3091.2002.00471.x.

Yavari-Ramshe, S., & Ataie-Ashtiani, B. (2016). Numerical modeling of subaerial and submarine landslide-generated tsunami waves—recent advances and futurechallenges. Landslides, 13(6), 1325–1368. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10346-016-0734-2.

Ye, L., Kanamori, H., Rivera, L., Lay, T., Zhou, Y., Sianipar, D., et al. (2020). The 22 december 2018 tsunami from ank collapse of anak krakatau volcano during eruption. Science Advances, 6(3), eaaz1377. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.aaz1377.

Zengaffinen, T., Løvholt, F., Pedersen, G. K., & Harbitz, C. B. (2020). Effects of rotational submarine slump dynamics on tsunami-genesis-new insight from idealized models and the 1929 Grand Banks event. Special Publications: Geological Society, London, 500.

Acknowledgements

Open Access funding provided by Norwegian Geotechnical Institute. This project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under the Marie Sklodowska-Curie grant agreement No. 721403. Dr. Raphaël Paris is gratefully acknowledged for fruitful early discussions and for providing topo-bathymetric data. Prof. Peter Talling is gratefully acknowledged for profitable comments on an early draft of this paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix: Grid Refinement Tests

Appendix: Grid Refinement Tests

1.1 A.1 The Landslide Model

A grid refinement test using three different spatial resolutions, \(\varDelta x_B = 73\,\mathrm {m}\), \(36\,\mathrm {m}, 18\,\mathrm {m}\), for the landslide model BingClaw is executed. The finest resolution \(\varDelta x_B = 18\,\mathrm {m}\) is the reference resolution. The maximum landslide thickness shows a deviation of 15% between the reference resolution and \(\varDelta x_B = 73\,\mathrm {m}\), and 4% between the reference resolution and \(\varDelta x_B = 36\,\mathrm {m}\) (see upper panels in Fig. 16). A resolution of \(\varDelta x_B = 36\,\mathrm {m}\) is applied for further analyses. In BingClaw we employ an adaptable time step, such that the CFL numbers are always below 0.8 and with a preference value of 0.65 (LeVeque 2002).

1.2 A.2 Landslide Updating Within Tsunami Model

The source term in the tsunami model is the volume displacement from the landslide model, which is updated at a certain frequency. We tested the following update frequencies of the landslide source into the tsunami model GeoClaw: \(\varDelta f = 12\,\mathrm {min}^{-1}, 4\,\mathrm {min}^{-1}, 2\,\mathrm {min}^{-1}, 1\,\mathrm {min}^{-1}\), with \(\varDelta f = 12\,\mathrm {min}^{-1}\) being the reference frequency. The surface elevations outside the source area deviate 8% between the reference frequency and \(\varDelta f = 12\,\mathrm {min}^{-1}\), but less than 1% for \(\varDelta f = 4\,\mathrm {min}^{-1}\). We apply \(\varDelta f = 4\,\mathrm {min}^{-1}\) for further analyses (i.e. updating the landslide source terms every \(15\,\mathrm {s}\)).

Landslide evolution for various spatial grid resolutions in a transect \(15\,\mathrm {s}\) and \(60\,\mathrm {s}\) after failure. The transect is shown in Fig. 2

1.3 A.3 The GeoClaw Model

We tested various spatial resolutions for GeoClaw, \(\varDelta x_G = 351\,\mathrm {m}, 175\,\mathrm {m}, 87\,\mathrm {m}\), shown as time series at all four gauges in Fig. 9. The average deviation of the leading crest between the reference resolution (\(\varDelta x_G = 87\,\mathrm {m}\)) and \(\varDelta x_G = 351\,\mathrm {m}\) is \(44\%\) for all four gauges. The same average deviation for \(\varDelta x_G = 175\,\mathrm {m}\) is \(10\%\). The resolution \(\varDelta x_G = 175\,\mathrm {m}\) represents a reasonable compromise concerning model inaccuracies and large computation times when using the reference resolution. A visual inspection of wave periods and first arrival times, in Fig. 9, suggest a relatively good match between \(\varDelta x_G = 175\,\mathrm {m}\) and the reference resolution. We apply a spatial resolution of \(\varDelta x_G = 175\,\mathrm {m}\) for further analyses. We refined two specific regions near the coasts (see Fig. 4) down to a grid resolution of \(11\,\mathrm {m}\) for the inundation study. As for BingClaw, an adaptable time step is employed, this time with a CFL-number maximum of 1.0 and 0.75 as desired value.

1.4 A.4 The GloBouss Model

In GloBouss we applied grid resolutions of \(\varDelta x_{Gl} = 200\,\mathrm {m}, 100\,\mathrm {m}, 50\,\mathrm {m}\), with the latter being the reference resolution. For both LSW and dispersive equations, the first crest deviates with \(25\%\) between the reference resolution and \(\varDelta x_{Gl} = 200\,\mathrm {m}\), and with \(6\%\) between \(\varDelta x_{Gl} = 100\,\mathrm {m}\) and the reference resolution. We apply \(\varDelta x_{Gl} = 100\,\mathrm {m}\) for further analyses. The time step is kept constant in GloBouss. For the LSW equations we used a time step that gave a maximum CFL number of 0.60. For the disp equations the model is implicit and hence more stable. Thus, the maximum CFL number is chosen as 7.22. This gives a more favourable time step in the shallow regions of the Sunda Strait.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zengaffinen, T., Løvholt, F., Pedersen, G. et al. Modelling 2018 Anak Krakatoa Flank Collapse and Tsunami: Effect of Landslide Failure Mechanism and Dynamics on Tsunami Generation. Pure Appl. Geophys. 177, 2493–2516 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00024-020-02489-x

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00024-020-02489-x