Abstract

Neurological disorders such as Alzheimer’s disease (AD), Lewy body dementia (LBD), frontotemporal dementia (FTD), and vascular dementia (VCID) have no disease-modifying treatments to date and now constitute a dementia crisis that affects 5 million in the USA and over 50 million worldwide. The most common pathological hallmark of these age-related neurodegenerative diseases is the accumulation of specific proteins, including amyloid beta (Aβ), tau, α-synuclein (α-syn), TAR DNA-binding protein 43 (TDP43), and repeat-associated non-ATG (RAN) peptides, in the intra- and extracellular spaces of selected brain regions. Whereas it remains controversial whether these accumulations are pathogenic or merely a byproduct of disease, the majority of therapeutic research has focused on clearing protein aggregates. Immunotherapies have garnered particular attention for their ability to target specific protein strains and conformations as well as promote clearance. Immunotherapies can also be neuroprotective: by neutralizing extracellular protein aggregates, they reduce spread, synaptic damage, and neuroinflammation. This review will briefly examine the current state of research in immunotherapies against the 3 most commonly targeted proteins for age-related neurodegenerative disease: Aβ, tau, and α-syn. The discussion will then turn to combinatorial strategies that enhance the effects of immunotherapy against aggregating protein, followed by new potential targets of immunotherapy such as aging-related processes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Age-related neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s disease (AD), Parkinson’s disease (PD), dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB), frontotemporal dementia (FTD), and vascular dementia (VCID) are being increasingly classified as major public health concerns [1]. In a rapidly aging world in which people over the age of 65 are projected to make up a fifth of the population in just 30 years, the prevalence of these dementias is expected to triple within that same time frame [1,2,3]. However, there are few, if any, disease-modifying treatments to date, making dementia one of the costliest conditions to society [4].

In response to this public health emergency, many countries have established national plans to address the lack of therapies [5, 6]. In 2011, the USA enacted the National Alzheimer’s Project Act (NAPA) (Public Law 111-375). The Act defines “Alzheimer’s” as Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias (ADRDs), including FTD, DLB, and VCID. The law calls for the development of treatments to prevent or slow the rate of AD progression by the year 2025, as well as a national plan and coordination among international bodies to fight AD on a global scale [7]. As a result, funding for AD research via the National Institute on Aging (NIA) has increased substantially within the last 5 years, jumping from 600 million dollars per year to approximately 2.8 billion. The NIA and its sister institutes and centers at the National Institutes of Health (NIH), including the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS), use milestones and recommendations from the AD Summits held at the NIH Bethesda campus to prioritize areas of research.

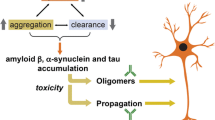

The most common pathological hallmark of age-related neurodegenerative diseases is the accumulation of proteinaceous deposits in the intra- and extracellular spaces of selected brain regions [8,9,10,11,12,13]. These proteins have been shown to accumulate several years prior to clinically observable cognitive, behavioral, and motor symptoms [14, 15]. Whereas there remains some debate as to whether protein accumulation is pathogenic or merely a byproduct of disease [16] (Fig. 1), the majority of therapeutic research has been focused on clearing these aggregates [17,18,19,20]. AD, DLB, PD, and FTD are thus often defined as proteinopathies of the aging population that display selective degeneration of neuronal circuitries and progressive accumulation of specific proteins such as amyloid beta (Aβ), tau, α-synuclein (α-syn), TAR DNA-binding protein 43 (TDP43), and repeat-associated non-ATG (RAN) [10, 21,22,23,24,25] among many others (Fig. 1). AD plaque and tangle formation are most frequently associated with Aβ and tau, whereas the primary protein component of Lewy bodies in PD and DLB is α-syn [23,24,25,26,27,28,29] (Fig. 2). FTD aggregates are generally comprised of tau, TDP-43, or Fused in sarcoma (FUS) [30, 31], but cases with a GGGGCC expansion mutation in intron 1 of the C9ORF72 gene also present with accumulations of TDP43 and repeat-associated non-AUG-dependent (RAN) translation proteins [32]. It must be pointed out, however, that α-syn and TDP43 aggregates are also commonly found in AD, as well as Aβ, tau, and TDP43 in DLB [33,34,35,36,37,38,39] (Fig. 2). Moreover, recent studies have shown significant overlap in AD and PD pathology in which a single individual over the age of 80 can present with aggregates of several of the above proteins [36] (Fig. 2). As such, simultaneously targeting multiple aggregating protein species may be more effective at treating these disorders than monotherapy [36, 37].

Combined mechanisms of neurodegeneration in AD/ADRD include protein accumulation and aging-related pathways. In the neurodegenerative process of AD/ADRD, synaptic damage and neuroinflammation may lead to neuronal dysfunction which results in dementia and motor deficits. The leading hypothesis is that progressive accumulation of proteins such as amyloid beta (Aβ), tau, α-synuclein (α-syn), TAR DNA-binding protein 43 (TDP43), and repeat-associated non-ATG (RAN) is the primary culprit. However, aging is also likely to play a critical role in pathogenesis, either in synergy with protein accumulation or as an independent pathway. Aging processes relevant to neurodegeneration include inflammation, proteostasis, DNA damage, cell senescence, and mitochondrial alterations

Overlapping protein aggregate pathology in AD/ADRD. Although Aβ and tau are classically associated with AD, α-syn with Lewy body dementia, and TDP43 and tau with FTD and limbic associated TDP43 encephalopathy (LATE), it is becoming increasingly evident that older individuals with dementia (+ 80 years old) display mixed pathology

Abnormal protein accumulation reflects an imbalanced proteostasis network [22, 40, 41]. How these protein aggregates lead to neurodegeneration is unclear but may involve synaptic dysfunction and neuroinflammation triggered by the formation of neurotoxic oligomers and the cell-to-cell propagation of oligomers, protofibrils, and fibrils [21, 22, 40, 42]. Given that age is the greatest risk factor for neurodegenerative disease, age-related alterations in proteostasis, inflammation, stem cell biogenesis, mitochondrial alterations, cell senescence, and DNA damage/repair [43] might also play critical roles in pathogenesis (Fig. 1). Understanding the role of protein homeostasis as it relates to aging could identify new drug targets and delineate reliable markers to accurately determinate a patient’s prognosis and appropriate treatment options [44].

Research on disease-modifying therapies has primarily focused on reducing the accumulation and propagation of protein aggregates by decreasing synthesis and aggregation or enhancing the rate of clearance [22, 45] (Fig. 3), with less emphasis on targeting aging-related processes. These include gene therapy to bolster clearance and degradation (e.g., autophagy, proteolysis, lysosomal degradation) [46], anti-sense technology to block synthesis (e.g., tau and α-syn genes) [47,48,49], small molecules to decrease aggregation (e.g., inhibitors of Aβ, tau, and α-syn oligomers and higher-order aggregates) [50,51,52,53], and immunotherapy to enhance clearance, degradation, and decrease aggregation (Fig. 3). Immunotherapies have garnered particular attention for their specificity [54, 55]. This review will discuss 2 types of immunotherapy: active vaccines, in which inactivated fragments of the pathogenic protein are directly administered to produce a long-lasting immune response, and passive immunization, in which patients are infused with antibodies against the target protein. Both strategies can modulate inflammation, prevent future oligomerization and aggregation activity [56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66], and promote clearance by phagocytic microglia or lysosomal degradation via the endosomal sorting complexes required for transport (ESCRT) pathway [67]. Other immunotherapy modalities, including T-cell modulation or harnessing cellular immunity to target neurodegeneration pathways, are discussed elsewhere [68, 69].

Mechanisms of protein toxicity in AD/ADRD involve oligomerization and propagation of protein aggregates. In neurodegeneration, an imbalance in the synthesis, aggregation, and clearance of proteins results in chronic accumulation, leading to further aggregation and propagation, and eventually inflammation and neurodegeneration

In addition to the various mechanisms above, immunotherapy has many other advantages. Its inherent specificity allows for selective targeting of specific strains and conformations with less off-target effects [61, 70,71,72] (Fig. 4). Polyvalent single-chain antibodies or combinations of antibodies and vaccines may also allow for the simultaneous targeting of multiple protein aggregate species [60, 73,74,75,76] (Fig. 4). Furthermore, immunotherapies can be neuroprotective by neutralizing extracellular protein aggregates and thereby reducing subsequent spread, synaptic damage, and neuroinflammation [77]. The very concept of immunotherapy for AD originated from the observation that the amyloid-β (Aβ) peptide accumulates extracellularly and is therefore accessible to antibodies that can recruit microglia to clear such deposits [78] (Fig. 4). It was accordingly considered unlikely that intracellular protein aggregates such as those of tau, α-syn, TDP43, and RAN would be good targets for immunotherapy. However, the advent of new technology to facilitate intracellular trafficking of antibodies [79,80,81,82] and the discovery that these so-called intracellular proteins also exist in cell membranes and extracellular spaces have driven immunotherapy development forward for PD, DLB, and FTD [59, 62, 63, 83, 84].

Multiple mechanisms of action of immunotherapy in AD/ADRD. Immunotherapy involves various mechanisms of action to target protein aggregates in the membrane and the intra- and extracellular spaces. Antibodies can block propagation, trigger lysosomal clearance of proteins, reduce inflammation, and promote neuroprotection

In March 2019, 20 years after the original publication by Schenk et al. that propelled the field of immunotherapy for neurodegenerative diseases [78], clinical trials for the Aβ antibody aducanumab were halted early for futility. One of the most promising AD therapies had become yet another failed drug to meet clinical endpoints after reaching phase III. Seven months later, however, the company sponsoring the trial surprised the world by announcing that the results of the futility analysis were premature, and that they would seek US Food and Drug Administration approval by using a larger dataset with longer exposure times to a high dose [85].

The news, while providing renewed hope for AD patients and families, should be received with cautious optimism [86]. Years of clinical trial failures for AD suggest that monotherapy against aggregation-prone proteins may not be enough for clinical efficacy [17]. Identifying an effective treatment for the heterogeneous group of patients affected by neurodegenerative disease may rest on an amalgamation of factors, including developing accurate and early diagnostic techniques, pursuing earlier preventive treatment, simultaneously targeting different proteins, identifying novel targets and age-related pathogenic cascades, and even reducing variability between clinical trial populations such as ApoE4 carrier status [77, 87, 88]. This review will briefly examine the current state of research in immunotherapies against the 3 most commonly targeted proteins for age-related neurodegenerative disease, Aβ, tau, and α-syn. The discussion will then turn to combinatorial strategies and new potential targets for future immunotherapy development.

Immunotherapies Targeting Aβ

Based on the amyloid cascade hypothesis, the transmembrane amyloid precursor protein (APP) can undergo proteolytic cleavage by β-secretase 1 (BACE1) to produce a soluble extracellular fragment and a cell membrane-bound fragment [89,90,91]. With its catalytic subunit presenilin, γ-secretase further cleaves the cell membrane fragment to release the amyloid-β (Aβ) peptide. Mutations in the genes encoding APP or presenilin carry the greatest incidence of familial AD [92]. Under nonpathological conditions, there is evidence that Aβ is involved in regulating synaptic function and even acting as an antimicrobial peptide to protect against infection and injury [93,94,95]. The Aβ peptide can be of varying lengths, the most prevalent being Aβ40. Longer forms, such as Aβ42, are less soluble and are prone to accumulate extracellularly to form oligomers, protofibrils, fibrils, and ultimately, plaques [90, 91, 96,97,98].

In 1999, Schenk et al. published the first immunotherapy for AD: an active vaccine called AN-1792 and comprised of synthetic full-length Aβ42 with QS-21 adjuvant [99]. The vaccine produced long-lasting and nearly complete clearance of Aβ deposits in many patients, but had no impact on the prominent tau pathology and severe dementia [100, 101]. The trial was halted after 4 patients developed meningoencephalitis related to T-cell infiltration. Successful mapping of the B-cell epitope to the N-terminus of Aβ [102,103,104] and additional work on Th2-biased adjuvants [103,104,105,106,107] were thus essential to the future Aβ vaccine development, allowing for a robust antibody response without the potentially harmful Th1 lymphocyte activation [108]. Vanutide cridificar (ACC-001) was designed as such to include only the B-cell epitope of Aβ plus QS-21 adjuvant [109]. Phase II trials for ACC-001, however, did not reach efficacy endpoints for cognitive evaluations, volumetric brain MRI, and CSF biomarkers, and development was halted in 2013 [110, 111]. Another recent strategy has been to use mimotopes, synthetic peptides that closely resemble the target protein epitope, as active vaccines. AFFITOPE® AD02 by Affiris (Wien, Austria), a 6-amino-acid peptide that mimics the Aβ N-terminus, was regrettably also terminated in phase II for lack of clinical efficacy [112].

There are currently 4 active immunizations being tested in phase II trials. CAD106 from Novartis (Basel, Switzerland) fuses a Qβ virus-like particle to multiple copies of the Aβ N-terminus (a.a. 1-6) [113, 114], and is being tested in homozygous ApoE4 carriers as part of the Alzheimer’s Prevention Initiative (API) program (NCT02565511) [115]. Similarly, ACI-24 by AC Immune (Lausanne, Switzerland) uses Aβ1-15 peptides anchored to the surface of a liposome and is being tested for mild-to-moderate Alzheimer’s disease and Down’s syndrome [116]. Another N-terminus vaccine, UB-311, is comprised of 2 synthetic Aβ1-14-targeting peptides linked to helper T-cell peptide epitopes contained in a Th2-biased formula [117]. After completing phase IIa trials for UB-311, United Neuroscience (Dublin, Ireland) is now assessing long-term safety, tolerability, and immunogenicity in an extension study (NCT03531710). ABVac40 by Araclon Biotech S.L. (Zaragoza, Spain) began phase II trials (NCT03461276) in mild cognitive impairment (MCI) last year and is the only vaccine to use the C-terminal end of Aβ40 [118].

The first passive immunotherapy to reach phase III trials was bapineuzumab, the humanized murine monoclonal antibody 3D6 [119,120,121] (Table 1). Bapineuzumab targets the Aβ N-terminus to mediate clearance of both soluble and fibrillar forms, but did not meet clinical endpoints in phase III and, moreover, produced amyloid-related imaging abnormalities (ARIA) with edema in patients that received a high dose [122]. Solanezumab, humanized murine antibody m266, is specific for soluble monomeric Aβ and is proposed to operate by the peripheral sink hypothesis, in which removal of Aβ in the periphery also leads to a reduction in the brain by passive diffusion [123]. Multiple phase III trials, including one in early AD patients, either failed to meet clinical efficacy or were terminated early for futility [124, 125] (Table 1). Similarly, phase III trials for crenezumab, human monoclonal IgG4 against oligomeric, fibrillar, and plaque conformations of Aβ, were stopped early in Jan 2019 for futility [126]. However, a phase II prevention trial with crenezumab in Presenilin1 (PSEN1) E280A mutation carriers (NCT01998841) is still underway as part of the API-Autosomal-Dominant Alzheimer’s Disease (ADAD) trial in Medellin, Colombia [127] (Table 1). The study is expected to be completed in February 2022 with the primary outcome being change in API ADAD Composite Cognitive Test Total Score at 260 weeks after baseline. Secondary outcomes include time to MCI or dementia progression because of AD, PET assessment of fibrillar amyloid accumulation, volumetric measurements by MRI, CSF tau biomarker levels, and various measures of memory and neurocognitive function.

Aducanumab was originally slated to take its place among the failed phase III immunotherapy candidates despite being shown to selectively reduce Aβ plaques and slow cognitive decline in earlier trials [128, 129]. Although phase III was halted earlier this year, the company that developed this antibody is now seeking FDA approval with new analysis of a larger data set [85, 130] (Table 1). Similarly, although development of human IgG1 gantenerumab was halted in 2014 for futility, a new phase III trial was initiated at a higher dose (NCT03444870) after the open label extension demonstrated a dramatic decline in Aβ deposition in participants [131]. Both gantenerumab and solanezumab are also being revived as potential preventative therapies by the Dominantly Inherited Alzheimer Network Trials Unit (DIAN-TU) in patients with AD-causing mutations (NCT01760005) [132]. Unfortunately, topline analyses in February 2020 showed that both drugs failed to meet primary endpoints [133]. Preventative trials for sporadic AD are also underway, in which the so-called A4 phase III trial (NCT02008357) tests solanezumab at higher doses and for longer durations in asymptomatic patients with preclinical AD as defined by positive amyloid PET scans [134]. This phase III trial recruited over 1200 participants and will be reporting in the next couple of years. Humanized murine mAb158 BAN2401 (NCT03887455) is the only other passive immunotherapy currently in phase III, but has already produced very promising results in phase II. Specifically, the 18-month study demonstrated a statistically significant slowing in cognitive decline at the highest dose with less than 10% of subjects experiencing ARIA [135]. The antibody is specific to soluble Aβ protofibrils, which have been proposed to be the toxic species rather than the plaques themselves [136] (Table 1).

In conclusion, despite previous failures in phase III immunotherapy trials targeting Aβ, interest has resurged following the recent glimmer of promising results coupled to advances in the early diagnosis and biomarker accessibility of AD. The antibodies currently being tested in clinical trials target a variety of Aβ species, including soluble, oligomeric, and fibrillar Aβ. Mechanisms of action include microglia-facilitated removal of extracellular amyloid oligomers and fibrils, blocking primary and secondary Aβ nucleation, and targeting monomers and soluble Aβ in the periphery that could otherwise trigger Aβ accumulation in the CNS. Rather than for late-stage disease reversal, immunotherapy against Aβ aggregates appears to be more appropriate for prevention initiatives with prolonged treatments past 78 weeks at high doses guided by reliable biomarkers. ApoE4 carriers exposed to high doses, however, are susceptible to complications such as ARIA-E and may need to be closely monitored by MRI [137].

Immunotherapies Targeting α-Synuclein

Diseases characterized by progressive α-syn accumulation in neuronal and non-neuronal cells of cortical and subcortical regions are collectively termed synucleinopathies, and include PD, DLB, multiple system atrophy (MSA), and a subset of AD [22, 26, 138, 139]. DLB/PD is the second most common cause of dementia and parkinsonism in the aging population after AD, affecting about 1 million in the USA [140]. α-syn is a presynaptic protein reported to be involved in endosomal formation and vesicle release at the synapse [141, 142]. The pathological hallmarks of PD and DLB are intraneuronal occlusions called Lewy bodies and Lewy neurites that are composed of fibrillar α-syn along with cytoskeletal and other synaptic proteins [143]. α-syn accumulation can also occur in glia, such as glial cytoplasmic inclusion (GCIs) in MSA patient oligodendrocytes or Lewy body-like structures in the amygdala, hippocampus, and neocortex of AD and Down syndrome patients [143,144,145]. Although astrocytes and microglia do not constitutively express α-syn, they actively uptake extracellular α-syn which can lead to glial aggregates in conditions of impaired clearance [146,147,148]. This is supported by increasing evidence that small amounts of α-syn aggregates are released from neurons into the extracellular space and subsequently interact with glial receptors such as Toll-like receptor 2 to trigger a pro-inflammatory response [40, 146, 149,150,151,152].

The original approach to use antibodies to target and remove amyloid plaques from the brain made intuitive sense given that Aβ aggregates are found in the extracellular space [99]. It was unclear how this method might be applied to DLB, PD, and other synucleinopathies, as the majority of the proteinaceous aggregates were thought to form within neurons of the striatonigral system, limbic areas, and deep layers of the neocortex. In the early 2000s, however, we showed that immunization of a newly developed α-syn transgenic model (Line D, PDGF-α-syn wt) with recombinant human α-syn mixed with Freund adjuvant resulted in the production of high titer antibodies against C-terminal α-syn that were capable of removing α-syn aggregates in neurons and ameliorating neurodegeneration and functional deficits [153]. Through additional active and passive immunization experiments in transgenic, viral, and preformed fibril injection models [154, 155], we learned that these antibodies had multiple mechanisms of action, such as recognizing α-syn aggregates in the membrane and triggering endocytosis and clearance via autophagy, lysosomal activity, or proteasomal degradation [156,157,158,159] (Fig. 4). Moreover, antibodies can be trafficked intracellularly with single-chain antibodies or intrabodies specifically engineered to penetrate the cell membrane via apolipoprotein B (ApoB), TAT fusion proteins, or uptake by endogenous receptors [160,161,162,163,164,165] (Fig. 4). Single-chain variable fragments (scFvs), for example, are designed to retain the specificity of the original full-length antibody without activating unwanted Fc-mediated responses [160, 161, 166]. Several studies have shown that transgenic mice injected with viral vectors encoding scFvs against Aβ [167,168,169], α-syn [81, 170], or tau [171, 172] show long-term in vivo scFv expression, improved functional deficits, and reduced pathogenic protein accumulation. Intrabody technology is continuing to be improved, such as in a recent study in which Chatterjee et al. (2018) enhanced the solubility of single-domain immunoglobulin fragments by engineering a polypeptide tether construct, and demonstrated its protective effects on motor function when delivered by gene therapy to a PD rodent model [173].

These intrabodies and cell-penetrating single-chain antibodies can block aggregation and target α-syn for degradation in the lysosomes using the ESCRT system [73, 81, 174, 175]. Antibodies can also block α-syn oligomerization and fibrillation, target specific strains and isoforms, prevent cell-to-cell transmission, and facilitate clearance via microglia [61, 149, 155, 176]. Therefore, antibodies can target both intracellular and extracellular α-syn aggregates as they spread from cell to cell (Fig. 4). This approach has been since applied to other proteinopathies with predominantly intracellular accumulations of tau, TDP43 [177, 178], SOD1 [179,180,181], RAN peptides [32], and Huntingtin (Htt) [182, 183]. Additional lessons from α-syn immunotherapy studies include the use of antibodies to develop blood, CSF, and tissue biomarkers to monitor the effects of immunotherapy and the ability of C-terminus-specific antibodies to block protease-mediated C-terminus truncation of α-syn and subsequently prevent oligomerization and transmission [59, 153, 156,157,158] (Fig. 4).

In this context, 2 main strategies for α-syn immunotherapy have been pursued: mimotope vaccines and antibodies against the N- or C-terminal ends of α-syn or specific conformations of oligomeric and fibrillar α-syn (Fig. 4). Whereas most antibodies have been developed with recombinant or synthetic α-syn monomers or aggregates, a recent and novel variant uses antibodies cloned from human healthy volunteers producing high titers of auto-antibodies against α-syn [184,185,186]. As a result of seminal cell-free in vitro and in vivo studies, several immunotherapies are currently been tested in clinical trial for synucleinopathies. The vaccines AFFITOPE® PD01A and PD03A were well tolerated in phase I and produced a dose-dependent immune response in patients with early MSA, but plans for phase II have yet to be disclosed [187, 188]. For passive immunotherapies, prasinezumab (also known as PRX002 or RO7046015) is a humanized monoclonal antibody against the C-terminus of α-syn undergoing phase II trials in patients with early PD (NCT03100149) [189] (Table 2). A phase I trial for BIIB054, a human monoclonal antibody that preferentially binds to aggregated α-syn, was recently concluded and showed favorable safety, tolerability, and pharmacokinetic profiles [190] (Table 2). MEDI1341 is also in phase I clinical trial testing (NCT03272165) as an antibody that can bind both monomers and aggregates. In preclinical studies, MEDI1341 was shown to readily cross the blood–brain barrier and block transmission of α-syn aggregates in a combined viral vector model [191] (Table 2).

In summary, antibodies against α-syn ameliorate Lewy body pathology by multiple mechanisms such as promoting the clearance of intracellular α-syn and blocking the propagation of extracellular α-syn. Other rising immunotherapy strategies are T-cell modulation, such as that of Copaxone® [192], and combinatorial approaches. We have tested several of such combinations, including simultaneous administration of 2 AFFITOPEs® against Aβ and α-syn [74, 193], nanoparticles containing both recombinant human α-syn and the immunomodulatory drug rapamycin, and the anti-inflammatory drug thalidomide given alongside a single-chain antibody against oligomeric α-syn derived from human DLB/PD brains and conjugated to ApoB [73]. Through these studies in DLB/PD mouse models, we show that combined immunotherapy may be more effective than monotherapy. This topic will be discussed in more detail in the following sections. The main challenge in the field of synucleinopathies is the lack of reliable and accessible biomarkers and the overlapping pathology among neurodegenerative diseases.

Immunotherapies Targeting Tau

Tau is a major member of the Microtubule Associated Proteins (MAP) family and abundantly expressed in neurons [194]. By binding to tubulin dimers, tau can stabilize microtubule formation and modulate cytoskeletal dynamics [195]. The degree to which tau is phosphorylated is an important regulator of microtubule stability [196]. Nonphosphorylated forms preferentially bind to microtubules, whereas hyperphosphorylation is associated with neurofibrillary tangle (NFT) formation from paired helical filaments (PHF) [197, 198]. Intracellular NFTs are a major hallmark lesion of AD and other neurodegenerative tauopathies such as FTD, cortico-basal degeneration, Pick’s disease, and progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP) [199]. The severity of tau pathology has been shown to correlate with the degree of cognitive impairment and neuronal loss [200,201,202,203], making the tau protein an attractive target for new immunotherapies.

Axon Neuroscience (Staré Mesto, Slovakia) recently completed a 24-month phase II trial for active tau vaccine AADvac1 (NCT02579252), announcing in September 2019 that the vaccine was safe and well-tolerated, and generated antibodies against pathological tau in over 98% of patients [204]. AADvac1 consists of a B-cell epitope from a cysteinated 12-mer tau peptide conjugated to keyhole limpet hemocyanin, a carrier protein that stimulates a Th2 immune response [205]. Based on the promising trends in cognitive improvement and decelerated accumulation of AD biomarkers in trial participants, Axon Neuroscience plans to move forward with the next phase of clinical trials and is also testing the vaccine for primary progressive nonfluent aphasia (NCT03174886) [206, 207]. In another active vaccine, ACI-35, 16 copies of synthetic tau fragments phosphorylated at Ser396 and Ser404 are embedded to the surface of a liposome [116, 208]. In August 2019, AC Immune announced a phase Ib/IIa trial in collaboration with Janssen Pharmaceuticals (Beerse, Belgium) to assess the safety, tolerability, and immunogenicity of the second generation of this vaccine, AC-35.030 [209].

AC Immune is also conducting phase 2 studies on the anti-tau passive immunotherapy Semorinemab (also called RO7105705, MTAU9937A, and RG6100) for prodromal/mild AD (NCT03289143) and moderate AD (NCT03828747) in partnership with Roche/Genentech (South San Francisco, CA). Other ongoing trials for passive anti-tau immunotherapies include that of Zagotenemab (also called LY3303560) in AD patients (NCT03518073) and ABBV-8E12 (also called Tilavonemab or C2N-8E12) for early AD (NCT02880956). Zagotenemab is the humanized mouse monoclonal antibody MC-1 and targets soluble tau aggregates [210]. Similarly, ABBV-8E12 is the humanized version of mouse monoclonal antibody HJ8.5 that was shown to reduce tau seeding, hyperphosphorylation, and cognitive deficits in P301S transgenic mice [211, 212]. Although phase II trials for ABBV-8E12 in PSP patients were halted in July 2019, favorable safety and tolerability profiles were obtained [213]. Gosuranemab (BIIB092), the humanized antibody against extracellular N-terminal tau from Biogen (Cambridge, MA), was also undergoing phase II trials for both PSP (PASSPORT) and AD (TANGO) [214, 215]. However, Biogen recently announced that topline results from the PASSPORT study failed to meet primary endpoints and that it would no longer pursue development of gosuranemab for PSP and other primary tauopathies [216].

Interestingly, current preclinical studies seem to be stepping away from targeting N-terminal tau in favor of other epitopes. DC8E8 has been recently characterized as a promising antibody that targets tau at 4 homologous epitopes present in each microtubule binding domain repeat [217]. DC8E8 was shown to not only preferentially bind truncated pathological tau over physiological tau but also prevent both the formation of beta sheets and the uptake of tau into neurons via sulfated heparan proteoglycans (HSPGs) [218]. In another study, Courade et al. (2018) identified an antibody against the central region of tau, dubbed “antibody D,” that was effective at blocking tau seeding in vitro [219]. Albert et al. (2019) further observed that this central tau epitope antibody was more efficacious at preventing AD-like pathology and cell-to-cell transfer of tau in mice [84].

In summary, considerable efforts have been made for over 20 years in the development of immunotherapies for neurodegenerative disorders. Antibodies targeting Aβ have led the way with a number of phase III trials and at least one that reported meeting primary outcome measures, followed closely behind by a handful of immunotherapies for α-syn and tau in phase I and II trials. Whereas accessible biomarkers are currently available for Aβ- and tau-related pathologies to guide the immunotherapy trials, there is a pressing lack of such measures for synucleinopathies. The other challenge at hand is that older patients present with protein aggregates that are no longer primarily one pathologic protein species but comprised of Aβ, tau, α-syn, TDP43, and others, in addition to aging-related processes such as inflammation, proteotasis deficits, DNA damage, mitochondrial alterations, and stem cell alterations. Thus, there is a dire need to develop reliable biomarkers and powerful combinatorial therapies to address these polyproteinopathies and age-related pathophysiological alterations, as will be discussed in the following section.

Combinatorial Immunotherapies

Combination therapy is already a standard of treatment for many cancers [220] and chronic diseases including hypertension, CHF, epilepsy, and HIV [221]. Combinations of currently available treatments are already being shown to improve cognition and behavior in AD patients, such as coadministration of cholinesterase inhibitors and memantine [222, 223] and enhancing memantine efficacy with beta-asarone and tenuigenin [224]. Although a few AD mouse studies have tested combinations of lipid mediators [225] or naturally occurring dietary compounds [226], combinatorial therapeutics in neurodegenerative disease remains a largely underexplored field (Fig. 5). Monotherapy alone may be insufficient against the complex and overlapping pathophysiology of age-related neurodegenerative diseases. As such, there is a growing need to simultaneously target multiple aggregating proteins as well as modulate aging-related mechanisms that synergize with protein aggregation to trigger neurodegeneration (Fig. 5).

Combination immunotherapies for AD/ADRD targeting protein aggregates and aging-related pathways. Immunotherapy can also be used to target other pathogens and age-related pathogenic processes associated with aging. One such pathogen may be the herpes simplex virus (#1). Aging-related pathways that can be targeted with antibodies include inflammation (e.g., TNF, TLR2, inflammasome) (#2), senescent cells (e.g., DPP4) (#3), and immune surveillance cells (e.g., NK cells) (#4). Immunotherapies in neurodegeneration have been traditionally developed to target protein aggregates (e.g., Aβ, tau, α-syn, TDP43) (#5) alone or in combination (#6). Combination therapies may involve targeting multiple protein aggregates (#6) or protein aggregates (#5) and age-related pathways (#1–4)

Overlapping pathology has been well-documented in age-related neurodegenerative diseases, such as the presence of Lewy body-like pathology in AD [227,228,229,230,231,232]. One study reported that 30 to 40% of patients with PD copresent with Aβ plaques and NFTs [233, 234], whereas over 70% of DLB patients [235] and more than 50% of AD patients [236] may have overlapping and, as a result, more aggressive pathology [237]. Indeed, a growing amount of evidence suggests that this copathology directly impacts disease progression. For example, dementia in PD is associated with high levels of AD copathology [235, 238,239,240,241]. Several groups have also shown that α-syn can contribute to the formation of toxic Aβ and tau species, as well as vice versa [242]. Moreover, as stated earlier, demented individuals over the age of 80 present with multiple pathologies including Aβ, tau, α-syn, TDP43, inflammatory, and vascular alterations [36]. As such, one therapeutic strategy may be to target the clearance of more than one pathologic protein via immunotherapy.

For example, immunotherapies that generate a response against both α-syn and Aβ may be more effective than either alone given that α-syn and Aβ may directly interact in AD patients and APP transgenic models [243,244,245,246]. AD patients have been shown to display elevated levels of α-syn in the CSF [247, 248], and further, Aβ may promote α-syn aggregation and toxicity [249, 250]. In mouse models, hippocampal neurons with α-syn accumulations were found to be more susceptible to Aβ-mediated toxicity [251], whereas genetic depletion of α-syn prevented the degeneration of cholinergic neurons and attenuated behavioral deficits [39, 252]. Similarly, α-syn has been shown to directly interact with PSEN1, which is important for the proteolytic processing of the APP to yield Aβ [231]. α-syn infusion in APP Tg mice also blocked Aβ seeding but enhanced synaptic degeneration [253, 254], potentially by blocking SNARE-vesicle fusion in a cooperative manner [255]. We recently covaccinated a double transgenic mouse model of DLB (mThy1-hAPP- and mThy1-α-syn) with AFFITOPE peptides against Aβ (AD02) and α-syn (PD1A) [74]. Remarkably, targeting one protein often concomitantly lowered the accumulation of another, in which AD02 effectively reduced Aβ pathology as well as that of phosphorylated tau and α-syn. This study also noted potential additive effects, particularly in alleviating behavioral deficits, suggesting that a combined immunotherapy approach may be appropriate for the heterogenous pathology of AD and DLB and other age-related neurodegenerative diseases (Fig. 5).

Tau and α-syn were also found to colocalize in the same cellular compartments, particularly in axons [256]. Although both have been shown to form intracellular aggregations, unlike Aβ, α-syn can self-aggregate whereas tau requires an aggregation-inducing agent [257]. Many studies have demonstrated that α-syn interacts with and catalyzes the oligomerization of tau [258,259,260,261,262]. α-syn may also demonstrate 14-3-3 cochaperone activity on 14-3-3 targets, including tau, promoting mutual misfolding [263,264,265]. α-syn preformed fibrils were shown to induce intracellular tau aggregation in vivo [266], and may be closely involved in the GSK3β-mediated phosphorylation of tau in a reciprocal manner [267,268,269,270]. α-syn oligomers may induce a distinctly toxic tau oligomeric strain in a cross-seeding effect [271, 272] or even form coaggregates [273]. A recent paper also reported that an age-dependent reduction in glucocerebrosidase (GCase) activity was associated with accumulations of lipid-stabilized α-syn and phosphorylated tau [274]. As such, a combination of immunotherapies against both tau and α-syn may be especially effective for cases in which both tau and synuclein pathology are present, as it can not only remove existing aggregates and toxic species but also prevent future cross-seeding events.

The ultimate approach would be to develop immunotherapies that simultaneously target Aβ, tau, α-syn, TDP43, and inflammation (Fig. 5). This could be achieved by 1) combining vaccines against Aβ, tau, α-syn, and TDP43 among other proteins; 2) combining antibodies against Aβ, tau, α-syn, and TDP43; 3) combining passive and active immunization; or 4) using multivalent single-chain antibodies that can target 2 or more of these proteins simultaneously. Another approach would be to design antibodies to recognize a conformation that is similar across multiple protein aggregate species, rather than a specific sequence. Interestingly, studies in APP and α-syn transgenic models have demonstrated that some antibodies against oligomeric tau are effective at reducing α-syn, whereas others have suggested that antibodies against Aβ may also target tau [61, 275]. Moreover, a combined vaccination approach targeting Aβ and tau has been shown to decrease disease pathology in Tau22/5xFAD double transgenic mice [276]. As such, a combination of these polyfunctional antibodies is another way of maximizing the effectiveness of immunotherapy (Fig. 5).

Given the aforementioned copathology, immunotherapy may also be effective in combination with gene silencing approaches. Several studies have shown that α-syn and tau deletion in animal transgenic models can delay the onset of disease. For example, α-syn knockout prevented neurotoxin-induced neurodegeneration in MPTP and rotenone PD mouse models [277, 278]. Injecting modified anti-sense oligonucleotides (ASO) targeting SNCA similarly promoted survival of TH-positive neurons and ameliorated motor deficits in mice expressing wild-type or mutant human SNCA [49]. Another recent study found that tau deletion in A53T α-syn tg mice rescued some cognitive and synaptic deficits without affecting α-syn expression or phosphorylation [279]. Gene therapy is also progressing in human neurodegenerative diseases, most notably nusinersen for the neuromuscular disorder spinal muscular atrophy [280, 281]. As such, immunotherapy to clear existing aggregates and anti-sense therapy to prevent further translation of pathologic proteins may be a viable combination, particularly in early stages of the disease.

As pointed out at the beginning of this section, effective combination immunotherapy should target not only the protein aggregates but also age-related pathological processes contributing to neurodegeneration, such as inflammation and cell senescence. In this regard, although this review was focused on antibody-based immunotherapy, targeting cellular immunity is another attractive approach to treat neurodegenerative disorders given its ability to reduce the protein aggregate load by targeting T cells. We developed a mixed cellular and active immunization in which α-syn and rapamycin are simultaneously delivered in an antigen-presenting cell-targeting glucan microparticle (GP) vaccine system [193]. In this case, the α-syn peptide elicits the production of antibodies against α-syn, whereas rapamycin triggered the recruitment of Tregs into the CNS. In turn, the Tregs immunomodulate microglia and induce greater microglial clearance of α-syn aggregates and reduced neurodegeneration and inflammation in α-syn tg mice. This vaccine, collectively termed GP+RAP/α-syn, was capable of triggering neuroprotective Treg responses in synucleinopathy animal models, and the combined vaccine was more effective than the humoral or cellular immunization alone. These results demonstrate the promise of multifunctional vaccine approaches for the treatment of AD and DLB/PD.

Another interesting and novel approach would be to trigger immune surveillance by NK cells to target senescence cells for elimination [282]. Moreover, senescent and immune cells can be targeted with specific antibodies. For example, a recent study used antibodies against the surface molecule DPP4 (dipeptidyl peptidase 4) of senescent cells [283] to facilitate their clearance (Fig. 5). Antibodies against interleukins, tumor necrosis factor (TNF), and Toll-like receptors may also be effective at modulating the immune response in neurodegenerative disease [284,285,286,287]. Previous studies have shown that Aβ, tau, and α-syn toxicity are mediated by the inflammasome [288,289,290]. In the case of synucleinopathies, we have shown that extracellular α-syn aggregates bind to TLR2 to trigger neuroinflammation and neurodegeneration and that selective neutralizing antibodies against TLR2 were effective at blocking these effects and behavior deficits in α-syn tg animals [152, 291]. In fact, TLR2 has been developed as an important novel target for synucleinopathies [57, 292] (Fig. 5).

Pathogens such as viruses or bacteria have been proposed to contribute to progressive aggregate formation and chronic inflammation given the antimicrobial properties of Aβ and age-related impaired clearance mechanisms [293] (Fig. 5). As such, directly targeting these pathogens with immunotherapy may effectively attenuate neuroinflammation, particularly in combination with immunotherapies against aggregating protein. Infection with herpes simplex virus 1 (HSV-1) in AD patients has long received attention for its association with AD pathology and decreased cognitive function [294,295,296,297], although increasing work is being performed on other viruses such as herpes zoster, Epstein–Barr virus, and human cytomegalovirus [298,299,300,301]. Bacteria of particular interest include Chlamydia pneumoniae, Helicobacter pylori, and Porphyromonas gingivalis [302,303,304,305,306,307]. For a comprehensive review of the evidence pertaining to pathogenic agents in age-related neurodegenerative disease, please see Panza et al. [293].

In summary, we have described the need and potential directions for combinatorial immunotherapies that include active, passive, and cellular approaches against specific protein aggregates as well as age-related neurodegenerative pathways such as inflammation and cell senescence (Fig. 5). These immunotherapy approaches may certainly also be amenable for combination with gene therapy (e.g., anti-sense), small molecules (e.g., autophagy modulators, antiaggregation, senolytics), and nonpharmacological (e.g., exercise, diet, training) treatments. Combinatorial therapeutics will also open exciting opportunities for personalized medicine, including catering to different stages of disease. For example, immunotherapy with anti-sense as described above may be well-suited to presymptomatic stages of disease. Another early intervention may be to combine immunotherapy with means of upregulating proteostasis components such as chemical chaperones or gene therapy for BiP or XBP1 to prevent further misfolding and aggregation [308,309,310,311]. Following the onset of significant pathological changes or clinical symptoms, however, polyvalent immunotherapy may be needed to address the frequent presence of multiple pathogenic proteins. Combining polyvalent antibodies with stress signaling inhibitors or regenerative therapy may prevent further synaptic loss and delay progression of symptoms [312,313,314].

Furthermore, different combinations may be used to cater to not only the stage of disease but also the patient’s specific symptoms, lifestyle risk factors, and genetic risk factors. For instance, given alone, the therapeutic efficacy of statins or antihypertensives for AD [315,316,317,318,319,320,321] and PD [322,323,324,325,326,327,328] patients remains largely inconclusive. However, a patient presenting with overlapping pathology from both AD and VCID may benefit from a combination of protein-targeting immunotherapy and such cardiovascular disease treatments. Current preventative immunotherapy trials such as that of the API are also just the beginning of genetics-based treatments. Many key initiatives for genetics research in neurodegenerative disease, such as the International Parkinson Disease Genomics Consortium (IPDGC), are spearheading a movement for accessible analytics tools and diverse and representative data. In the future, we may be able to use this groundwork to identify a patient’s specific risk variants and ultimately design a combinatorial therapy that can address both the protein accumulation and the biological associations for those variants. Let it also not be forgotten, however, that in addition to further development of these therapeutic strategies, there is a dire need for an overhaul of current policy and clinical trial practices in order to truly pursue combinatorial and personalized medicine for diseases as complex as age-related neurodegeneration.

References

Ageing and health [Fact sheet on the Internet]. Geneva: World Health Organization. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/ageing-and-health. Accessed 10 Nov 2019.

Alzheimer’s Association. 2019 Alzheimer’s Disease Facts and Figures. Alzheimers Dement. 2019;15(3):321–87.

Dementia [Fact sheet on the Internet]. Geneva: World Health Organization. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/dementia. Accessed 10 Nov 2019.

Hurd MD, Martorell P, Langa KM. Monetary costs of dementia in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(5):489–90.

Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation (ASPE). National Plan to Address Alzheimer’s Disease. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Available from: https://aspe.hhs.gov/report/national-plan-address-alzheimers-disease-2016-update. Accessed 31 Aug 2016.

National dementia plans [Internet]. London: Alzheimer’s Disease International. Available from: https://www.alz.co.uk/dementia-plans. Accessed 01 Nov 2017

Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation (ASPE). National Alzheimer’s Project Act. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Available from: https://aspe.hhs.gov/national-alzheimers-project-act. Accessed 10 Oct 2019.

Bossy-Wetzel E, Schwarzenbacher R, Lipton SA. Molecular pathways to neurodegeneration. Nat Med. 2004;10 Suppl:S2–9.

Chung CG, Lee H, Lee SB. Mechanisms of protein toxicity in neurodegenerative diseases. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2018;75(17):3159–80.

Trojanowski JQ, Lee VM. “Fatal attractions” of proteins. A comprehensive hypothetical mechanism underlying Alzheimer’s disease and other neurodegenerative disorders. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2000;924:62–7.

Forman MS, Trojanowski JQ, Lee VM. Neurodegenerative diseases: a decade of discoveries paves the way for therapeutic breakthroughs. Nat Med. 2004;10(10):1055–1063.

Selkoe DJ, Hardy J. The amyloid hypothesis of Alzheimer’s disease at 25 years. EMBO Mol Med. 2016;8(6):595–608.

Marsh AP. Molecular mechanisms of proteinopathies across neurodegenerative disease: a review. Neurol Res Pract. 2019;1:35. https://doi.org/10.1186/s42466-019-0039-8.

Villemagne VL, Burnham S, Bourgeat P, Brown B, Ellis KA, Salvado O, et al. Amyloid beta deposition, neurodegeneration, and cognitive decline in sporadic Alzheimer’s disease: a prospective cohort study. Lancet Neurol. 2013;12(4):357–67.

Beason-Held LL, Goh JO, An Y, Kraut MA, O'Brien RJ, Ferrucci L, et al. Changes in brain function occur years before the onset of cognitive impairment. J Neurosci. 2013;33(46):18008–14.

Espay AJ, Vizcarra JA, Marsili L, Lang AE, Simon DK, Merola A, et al. Revisiting protein aggregation as pathogenic in sporadic Parkinson and Alzheimer diseases. Neurology. 2019;92(7):329–37.

Panza F, Lozupone M, Logroscino G, Imbimbo BP. A critical appraisal of amyloid-beta-targeting therapies for Alzheimer disease. Nat Rev Neurol. 2019;15(2):73–88.

Villemagne VL, Dore V, Burnham SC, Masters CL, Rowe CC. Imaging tau and amyloid-beta proteinopathies in Alzheimer disease and other conditions. Nat Rev Neurol. 2018;14(4):225–36.

Salardini A. An Overview of Primary Dementias as Clinicopathological Entities. Semin Neurol. 2019;39(2):153–66.

Jack CR, Jr., Bennett DA, Blennow K, Carrillo MC, Dunn B, Haeberlein SB, et al. NIA-AA Research Framework: Toward a biological definition of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2018;14(4):535–62.

Overk CR, Masliah E. Pathogenesis of synaptic degeneration in Alzheimer’s disease and Lewy body disease. Biochem Pharmacol. 2014;88(4):508–16.

Lashuel HA, Overk CR, Oueslati A, Masliah E. The many faces of alpha-synuclein: from structure and toxicity to therapeutic target. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2013;14(1):38–48.

DeTure MA, Dickson DW. The neuropathological diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease. Mol Neurodegener. 2019;14(1):32.

Chornenkyy Y, Fardo DW, Nelson PT. Tau and TDP-43 proteinopathies: kindred pathologic cascades and genetic pleiotropy. Lab Invest. 2019;99(7):993–1007.

Pievani M, Filippini N, van den Heuvel MP, Cappa SF, Frisoni GB. Brain connectivity in neurodegenerative diseases--from phenotype to proteinopathy. Nat Rev Neurol. 2014;10(11):620–33.

Spillantini MG, Schmidt ML, Lee VM, Trojanowski JQ, Jakes R, Goedert M. Alpha-synuclein in Lewy bodies. Nature. 1997;388(6645):839–40.

Takeda A, Mallory M, Sundsmo M, Honer W, Hansen L, Masliah E. Abnormal accumulation of NACP/alpha-synuclein in neurodegenerative disorders. Am J Pathol. 1998;152(2):367–72.

Dugger BN, Dickson DW. Pathology of Neurodegenerative Diseases. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2017;9(7):a028035. https://doi.org/10.1101/cshperspect.a028035.

Hansen LA, Masliah E, Terry RD, Mirra SS. A neuropathological subset of Alzheimer’s disease with concomitant Lewy body disease and spongiform change. Acta Neuropathol. 1989;78(2):194–201.

Goedert M, Ghetti B, Spillantini MG. Frontotemporal dementia: implications for understanding Alzheimer disease. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2012;2(2):a006254.

Ferrari R, Kapogiannis D, Huey ED, Momeni P. FTD and ALS: a tale of two diseases. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2011;8(3):273–94.

Zu T, Liu Y, Banez-Coronel M, Reid T, Pletnikova O, Lewis J, et al. RAN proteins and RNA foci from antisense transcripts in C9ORF72 ALS and frontotemporal dementia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110(51):E4968–77.

Josephs KA, Murray ME, Whitwell JL, Tosakulwong N, Weigand SD, Petrucelli L, et al. Updated TDP-43 in Alzheimer’s disease staging scheme. Acta Neuropathol. 2016;131(4):571–85.

Hanko V, Apple AC, Alpert KI, Warren KN, Schneider JA, Arfanakis K, et al. In vivo hippocampal subfield shape related to TDP-43, amyloid beta, and tau pathologies. Neurobiol Aging. 2019;74:171–81.

Sahoo A, Bejanin A, Murray ME, Tosakulwong N, Weigand SD, Serie AM, et al. TDP-43 and Alzheimer’s Disease Pathologic Subtype in Non-Amnestic Alzheimer’s Disease Dementia. J Alzheimers Dis. 2018;64(4):1227–33.

Robinson JL, Lee EB, Xie SX, Rennert L, Suh E, Bredenberg C, et al. Neurodegenerative disease concomitant proteinopathies are prevalent, age-related and APOE4-associated. Brain. 2018;141(7):2181–93.

Boyle PA, Yu L, Wilson RS, Leurgans SE, Schneider JA, Bennett DA. Person-specific contribution of neuropathologies to cognitive loss in old age. Ann Neurol. 2018;83(1):74–83.

Adamowicz DH, Roy S, Salmon DP, Galasko DR, Hansen LA, Masliah E, et al. Hippocampal alpha-Synuclein in Dementia with Lewy Bodies Contributes to Memory Impairment and Is Consistent with Spread of Pathology. J Neurosci. 2017;37(7):1675–84.

Spencer B, Desplats PA, Overk CR, Valera-Martin E, Rissman RA, Wu C, et al. Reducing Endogenous alpha-Synuclein Mitigates the Degeneration of Selective Neuronal Populations in an Alzheimer's Disease Transgenic Mouse Model. J Neurosci. 2016;36(30):7971–84.

Lee SJ, Desplats P, Sigurdson C, Tsigelny I, Masliah E. Cell-to-cell transmission of non-prion protein aggregates. Nat Rev Neurol. 2010;6(12):702–6.

Stefanis L, Emmanouilidou E, Pantazopoulou M, Kirik D, Vekrellis K, Tofaris GK. How is alpha-synuclein cleared from the cell? J Neurochem. 2019;150(5):577–90.

Brettschneider J, Del Tredici K, Lee VM, Trojanowski JQ. Spreading of pathology in neurodegenerative diseases: a focus on human studies. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2015;16(2):109–20.

Ferrucci L, Gonzalez-Freire M, Fabbri E, Simonsick E, Tanaka T, Moore Z, et al. Measuring biological aging in humans: A quest. Aging Cell. 2019;19(2):e13080. https://doi.org/10.1111/acel.13080.

Hodgson R, Kennedy BK, Masliah E, Scearce-Levie K, Tate B, Venkateswaran A, et al. Aging: therapeutics for a healthy future. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2019;108:453–58.

Citron M. Alzheimer’s disease: strategies for disease modification. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2010;9(5):387–98.

Sudhakar V, Richardson RM. Gene Therapy for Neurodegenerative Diseases. Neurotherapeutics. 2019;16(1):166–75.

DeVos SL, Miller RL, Schoch KM, Holmes BB, Kebodeaux CS, Wegener AJ, et al. Tau reduction prevents neuronal loss and reverses pathological tau deposition and seeding in mice with tauopathy. Sci Transl Med. 2017;9(374):eaag0481. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aag0481.

DeVos SL, Goncharoff DK, Chen G, Kebodeaux CS, Yamada K, Stewart FR, et al. Antisense reduction of tau in adult mice protects against seizures. J Neurosci. 2013;33(31):12887–97.

Uehara T, Choong CJ, Nakamori M, Hayakawa H, Nishiyama K, Kasahara Y, et al. Amido-bridged nucleic acid (AmNA)-modified antisense oligonucleotides targeting alpha-synuclein as a novel therapy for Parkinson’s disease. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):7567.

Price DL, Koike MA, Khan A, Wrasidlo W, Rockenstein E, Masliah E, et al. The small molecule alpha-synuclein misfolding inhibitor, NPT200-11, produces multiple benefits in an animal model of Parkinson's disease. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):16165.

Tatenhorst L, Eckermann K, Dambeck V, Fonseca-Ornelas L, Walle H, Lopes da Fonseca T, et al. Fasudil attenuates aggregation of alpha-synuclein in models of Parkinson’s disease. Acta Neuropathol Commun. 2016;4:39.

Wischik CM, Staff RT, Wischik DJ, Bentham P, Murray AD, Storey JM, et al. Tau aggregation inhibitor therapy: an exploratory phase 2 study in mild or moderate Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2015;44(2):705–20.

Gregori M, Taylor M, Salvati E, Re F, Mancini S, Balducci C, et al. Retro-inverso peptide inhibitor nanoparticles as potent inhibitors of aggregation of the Alzheimer’s Abeta peptide. Nanomedicine. 2017;13(2):723–32.

Liu YH, Giunta B, Zhou HD, Tan J, Wang YJ. Immunotherapy for Alzheimer disease: the challenge of adverse effects. Nat Rev Neurol. 2012;8(8):465–9.

Cummings J, Lee G, Ritter A, Sabbagh M, Zhong K. Alzheimer’s disease drug development pipeline: 2019. Alzheimers Dement (N Y). 2019;5:272–293.

Shin J, Kim HJ, Jeon B. Immunotherapy Targeting Neurodegenerative Proteinopathies: alpha-Synucleinopathies and Tauopathies. J Mov Disord. 2020;13(1):11–9.

Kwon S, Iba M, Masliah E, Kim C. Targeting Microglial and Neuronal Toll-like Receptor 2 in Synucleinopathies. Exp Neurobiol. 2019;28(5):547–53.

Katsinelos T, Tuck BJ, Mukadam AS, McEwan WA. The Role of Antibodies and Their Receptors in Protection Against Ordered Protein Assembly in Neurodegeneration. Front Immunol. 2019;10:1139.

Valera E, Spencer B, Masliah E. Immunotherapeutic Approaches Targeting Amyloid-beta, alpha-Synuclein, and Tau for the Treatment of Neurodegenerative Disorders. Neurotherapeutics. 2016;13(1):179–89.

Valera E, Masliah E. Combination therapies: The next logical Step for the treatment of synucleinopathies? Mov Disord. 2016;31(2):225–34.

Valera E, Masliah E. Immunotherapy for neurodegenerative diseases: focus on alpha-synucleinopathies. Pharmacol Ther. 2013;138(3):311–22.

Bittar A, Bhatt N, Kayed R. Advances and considerations in AD tau-targeted immunotherapy. Neurobiol Dis. 2019;134:104707.

Colin M, Dujardin S, Schraen-Maschke S, Meno-Tetang G, Duyckaerts C, Courade JP, et al. From the prion-like propagation hypothesis to therapeutic strategies of anti-tau immunotherapy. Acta Neuropathol. 2019;139:3–25.

Novak P, Kontsekova E, Zilka N, Novak M. Ten Years of Tau-Targeted Immunotherapy: The Path Walked and the Roads Ahead. Front Neurosci. 2018;12:798.

Wisniewski T, Goni F. Vaccination strategies. Handb Clin Neurol. 2018;153:419–30.

Schilling S, Rahfeld JU, Lues I, Lemere CA. Passive Abeta Immunotherapy: Current Achievements and Future Perspectives. Molecules. 2018;23(5):E1068. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules23051068.

Spencer B, Kim C, Gonzalez T, Bisquertt A, Patrick C, Rockenstein E, et al. alpha-Synuclein interferes with the ESCRT-III complex contributing to the pathogenesis of Lewy body disease. Hum Mol Genet. 2016;25(6):1100–15.

Liang Z, Zhao Y, Ruan L, Zhu L, Jin K, Zhuge Q, et al. Impact of aging immune system on neurodegeneration and potential immunotherapies. Prog Neurobiol. 2017;157:2–28.

Laurie C, Reynolds A, Coskun O, Bowman E, Gendelman HE, Mosley RL. CD4+ T cells from Copolymer-1 immunized mice protect dopaminergic neurons in the 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine model of Parkinson's disease. J Neuroimmunol. 2007;183(1–2):60–8.

Congdon EE, Lin Y, Rajamohamedsait HB, Shamir DB, Krishnaswamy S, Rajamohamedsait WJ, et al. Affinity of Tau antibodies for solubilized pathological Tau species but not their immunogen or insoluble Tau aggregates predicts in vivo and ex vivo efficacy. Mol Neurodegener. 2016;11(1):62.

Bittar A, Sengupta U, Kayed R. Prospects for strain-specific immunotherapy in Alzheimer's disease and tauopathies. NPJ Vaccines. 2018;3:9.

Wisniewski T, Goni F. Immunotherapeutic approaches for Alzheimer’s disease. Neuron. 2015;85(6):1162–76.

Valera E, Spencer B, Fields JA, Trinh I, Adame A, Mante M, et al. Combination of alpha-synuclein immunotherapy with anti-inflammatory treatment in a transgenic mouse model of multiple system atrophy. Acta Neuropathol Commun. 2017;5(1):2.

Mandler M, Rockenstein E, Overk C, Mante M, Florio J, Adame A, et al. Effects of single and combined immunotherapy approach targeting amyloid beta protein and alpha-synuclein in a dementia with Lewy bodies-like model. Alzheimers Dement. 2019;15(9):1133–48.

Bednar MM. Combination therapy for Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias. Prog Mol Biol Transl Sci. 2019;168:289–96.

Perry D, Sperling R, Katz R, Berry D, Dilts D, Hanna D, et al. Building a roadmap for developing combination therapies for Alzheimer’s disease. Expert Rev Neurother. 2015;15(3):327–33.

Kennedy RE, Cutter GR, Wang G, Schneider LS. Post Hoc Analyses of ApoE Genotype-Defined Subgroups in Clinical Trials. J Alzheimers Dis. 2016;50(4):1205–15.

Overk C, Masliah E. Dale Schenk One Year Anniversary: Fighting to Preserve the Memories. J Alzheimers Dis. 2018;62(1):1–13.

Messer A, Butler DC. Optimizing intracellular antibodies (intrabodies/nanobodies) to treat neurodegenerative disorders. Neurobiol Dis. 2019;134:104619.

Masliah E, Spencer B. Applications of ApoB LDLR-Binding Domain Approach for the Development of CNS-Penetrating Peptides for Alzheimer's Disease. Methods Mol Biol. 2015;1324:331–7.

Spencer B, Williams S, Rockenstein E, Valera E, Xin W, Mante M, et al. alpha-synuclein conformational antibodies fused to penetratin are effective in models of Lewy body disease. Ann Clin Transl Neurol. 2016;3(8):588–606.

Bhatt MA, Messer A, Kordower JH. Can intrabodies serve as neuroprotective therapies for Parkinson’s disease? Beginning thoughts. J Parkinsons Dis. 2013;3(4):581–91.

Wang Z, Gao G, Duan C, Yang H. Progress of immunotherapy of anti-alpha-synuclein in Parkinson's disease. Biomed Pharmacother. 2019;115:108843.

Albert M, Mairet-Coello G, Danis C, Lieger S, Caillierez R, Carrier S, et al. Prevention of tau seeding and propagation by immunotherapy with a central tau epitope antibody. Brain. 2019;142(6):1736–50.

Third Quarter 2019: Financial Results and Business Update. Cambridge: Biogen. Available from: https://investors.biogen.com/static-files/40565136-b61f-4473-9e58-9be769bbac6c. Accessed 12 Dec 2019.

Abbott A. Fresh push for ‘failed’ Alzheimer’s drug. Nature. Available from: https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-019-03261-5. Accessed 12 Dec 2019.

Petersen RC, Thomas RG, Aisen PS, Mohs RC, Carrillo MC, Albert MS, et al. Randomized controlled trials in mild cognitive impairment: Sources of variability. Neurology. 2017;88(18):1751–8.

Overk C, Masliah E. Could changing the course of Alzheimer’s disease pathology with immunotherapy prevent dementia? Brain. 2019;142(7):1853–5.

Hardy JA, Higgins GA. Alzheimer’s disease: the amyloid cascade hypothesis. Science. 1992;256(5054):184–5.

Selkoe DJ. The molecular pathology of Alzheimer’s disease. Neuron. 1991;6(4):487–98.

Hardy J, Allsop D. Amyloid deposition as the central event in the aetiology of Alzheimer’s disease. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 1991;12(10):383–8.

Lanoiselee HM, Nicolas G, Wallon D, Rovelet-Lecrux A, Lacour M, Rousseau S, et al. APP, PSEN1, and PSEN2 mutations in early-onset Alzheimer disease: A genetic screening study of familial and sporadic cases. PLoS Med. 2017;14(3):e1002270.

Russell CL, Semerdjieva S, Empson RM, Austen BM, Beesley PW, Alifragis P. Amyloid-beta acts as a regulator of neurotransmitter release disrupting the interaction between synaptophysin and VAMP2. PLoS One. 2012;7(8):e43201.

Soscia SJ, Kirby JE, Washicosky KJ, Tucker SM, Ingelsson M, Hyman B, et al. The Alzheimer’s disease-associated amyloid beta-protein is an antimicrobial peptide. PLoS One. 2010;5(3):e9505.

Eimer WA, Vijaya Kumar DK, Navalpur Shanmugam NK, Rodriguez AS, Mitchell T, Washicosky KJ, et al. Alzheimer’s Disease-Associated beta-Amyloid Is Rapidly Seeded by Herpesviridae to Protect against Brain Infection. Neuron. 2018;100(6):1527–32.

Beyreuther K, Masters CL. Amyloid precursor protein (APP) and beta A4 amyloid in the etiology of Alzheimer's disease: precursor-product relationships in the derangement of neuronal function. Brain Pathol. 1991;1(4):241–51.

Wiltfang J, Esselmann H, Bibl M, Smirnov A, Otto M, Paul S, et al. Highly conserved and disease-specific patterns of carboxyterminally truncated Abeta peptides 1–37/38/39 in addition to 1–40/42 in Alzheimer’s disease and in patients with chronic neuroinflammation. J Neurochem. 2002;81(3):481–96.

Maddalena AS, Papassotiropoulos A, Gonzalez-Agosti C, Signorell A, Hegi T, Pasch T, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid profile of amyloid beta peptides in patients with Alzheimer's disease determined by protein biochip technology. Neurodegener Dis. 2004;1(4–5):231–5.

Schenk D, Barbour R, Dunn W, Gordon G, Grajeda H, Guido T, et al. Immunization with amyloid-beta attenuates Alzheimer-disease-like pathology in the PDAPP mouse. Nature. 1999;400(6740):173–7.

Nicoll JAR, Buckland GR, Harrison CH, Page A, Harris S, Love S, et al. Persistent neuropathological effects 14 years following amyloid-beta immunization in Alzheimer’s disease. Brain. 2019;142(7):2113–26.

Vellas B, Black R, Thal LJ, Fox NC, Daniels M, McLennan G, et al. Long-term follow-up of patients immunized with AN1792: reduced functional decline in antibody responders. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2009;6(2):144–51.

Lemere CA, Maron R, Selkoe DJ, Weiner HL. Nasal vaccination with beta-amyloid peptide for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. DNA Cell Biol. 2001;20(11):705–11.

Lemere CA, Maron R, Spooner ET, Grenfell TJ, Mori C, Desai R, et al. Nasal A beta treatment induces anti-A beta antibody production and decreases cerebral amyloid burden in PD-APP mice. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2000;920:328–31.

Cribbs DH, Ghochikyan A, Vasilevko V, Tran M, Petrushina I, Sadzikava N, et al. Adjuvant-dependent modulation of Th1 and Th2 responses to immunization with beta-amyloid. Int Immunol. 2003;15(4):505–14.

Lemere CA, Spooner ET, Leverone JF, Mori C, Clements JD. Intranasal immunotherapy for the treatment of Alzheimer's disease: Escherichia coli LT and LT(R192G) as mucosal adjuvants. Neurobiol Aging. 2002;23(6):991–1000.

Maier M, Seabrook TJ, Lemere CA. Modulation of the humoral and cellular immune response in Abeta immunotherapy by the adjuvants monophosphoryl lipid A (MPL), cholera toxin B subunit (CTB) and E. coli enterotoxin LT(R192G). Vaccine. 2005;23(44):5149–59.

Asuni AA, Boutajangout A, Scholtzova H, Knudsen E, Li YS, Quartermain D, et al. Vaccination of Alzheimer’s model mice with Abeta derivative in alum adjuvant reduces Abeta burden without microhemorrhages. Eur J Neurosci. 2006;24(9):2530–42.

Liu B, Frost JL, Sun J, Fu H, Grimes S, Blackburn P, et al. MER5101, a novel Abeta1-15:DT conjugate vaccine, generates a robust anti-Abeta antibody response and attenuates Abeta pathology and cognitive deficits in APPswe/PS1DeltaE9 transgenic mice. J Neurosci. 2013;33(16):7027–37.

Arai H, Suzuki H, Yoshiyama T. Vanutide cridificar and the QS-21 adjuvant in Japanese subjects with mild to moderate Alzheimer’s disease: results from two phase 2 studies. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2015;12(3):242–54.

Ketter N, Liu E, Di J, Honig LS, Lu M, Novak G, et al. A Randomized, Double-Blind, Phase 2 Study of the Effects of the Vaccine Vanutide Cridificar with QS-21 Adjuvant on Immunogenicity, Safety and Amyloid Imaging in Patients with Mild to Moderate Alzheimer’s Disease. J Prev Alzheimers Dis. 2016;3(4):192–201.

Pasquier F, Sadowsky C, Holstein A, Leterme Gle P, Peng Y, Jackson N, et al. Two Phase 2 Multiple Ascending-Dose Studies of Vanutide Cridificar (ACC-001) and QS-21 Adjuvant in Mild-to-Moderate Alzheimer’s Disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2016;51(4):1131–43.

Schneeberger A, Hendrix S, Mandler M, Ellison N, Burger V, Brunner M, et al. Results from a Phase II Study to Assess the Clinical and Immunological Activity of AFFITOPE(R) AD02 in Patients with Early Alzheimer’s Disease. J Prev Alzheimers Dis. 2015;2(2):103–14.

Vandenberghe R, Riviere ME, Caputo A, Sovago J, Maguire RP, Farlow M, et al. Active Abeta immunotherapy CAD106 in Alzheimer’s disease: A phase 2b study. Alzheimers Dement (N Y). 2017;3(1):10–22.

Winblad B, Andreasen N, Minthon L, Floesser A, Imbert G, Dumortier T, et al. Safety, tolerability, and antibody response of active Abeta immunotherapy with CAD106 in patients with Alzheimer’s disease: randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, first-in-human study. Lancet Neurol. 2012;11(7):597–604.

Lopez Lopez C, Tariot PN, Caputo A, Langbaum JB, Liu F, Riviere ME, et al. The Alzheimer’s Prevention Initiative Generation Program: Study design of two randomized controlled trials for individuals at risk for clinical onset of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement (N Y). 2019;5:216–27.

Hickman DT, Lopez-Deber MP, Ndao DM, Silva AB, Nand D, Pihlgren M, et al. Sequence-independent control of peptide conformation in liposomal vaccines for targeting protein misfolding diseases. J Biol Chem. 2011;286(16):13966–76.

Wang CY, Wang PN, Chiu MJ, Finstad CL, Lin F, Lynn S, et al. UB-311, a novel UBITh((R)) amyloid beta peptide vaccine for mild Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement (N Y). 2017;3(2):262–72.

Lacosta AM, Pascual-Lucas M, Pesini P, Casabona D, Perez-Grijalba V, Marcos-Campos I, et al. Safety, tolerability and immunogenicity of an active anti-Abeta40 vaccine (ABvac40) in patients with Alzheimer’s disease: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase I trial. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2018;10(1):12.

Bard F, Cannon C, Barbour R, Burke RL, Games D, Grajeda H, et al. Peripherally administered antibodies against amyloid beta-peptide enter the central nervous system and reduce pathology in a mouse model of Alzheimer disease. Nat Med. 2000;6(8):916–19.

Buttini M, Masliah E, Barbour R, Grajeda H, Motter R, Johnson-Wood K, et al. Beta-amyloid immunotherapy prevents synaptic degeneration in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurosci. 2005;25(40):9096–101.

Zago W, Buttini M, Comery TA, Nishioka C, Gardai SJ, Seubert P, et al. Neutralization of soluble, synaptotoxic amyloid beta species by antibodies is epitope specific. J Neurosci. 2012;32(8):2696–702.

Salloway S, Sperling R, Fox NC, Blennow K, Klunk W, Raskind M, et al. Two phase 3 trials of bapineuzumab in mild-to-moderate Alzheimer’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(4):322–33.

DeMattos RB, Bales KR, Cummins DJ, Dodart JC, Paul SM, Holtzman DM. Peripheral anti-A beta antibody alters CNS and plasma A beta clearance and decreases brain A beta burden in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98(15):8850–5.

Doody RS, Thomas RG, Farlow M, Iwatsubo T, Vellas B, Joffe S, et al. Phase 3 trials of solanezumab for mild-to-moderate Alzheimer’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(4):311–21.

Honig LS, Vellas B, Woodward M, Boada M, Bullock R, Borrie M, et al. Trial of Solanezumab for Mild Dementia Due to Alzheimer’s Disease. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(4):321–30.

Ultsch M, Li B, Maurer T, Mathieu M, Adolfsson O, Muhs A, et al. Structure of Crenezumab Complex with Abeta Shows Loss of beta-Hairpin. Sci Rep. 2016;6:39374.

Tariot PN, Lopera F, Langbaum JB, Thomas RG, Hendrix S, Schneider LS, et al. The Alzheimer’s Prevention Initiative Autosomal-Dominant Alzheimer’s Disease Trial: A study of crenezumab versus placebo in preclinical PSEN1 E280A mutation carriers to evaluate efficacy and safety in the treatment of autosomal-dominant Alzheimer’s disease, including a placebo-treated noncarrier cohort. Alzheimers Dement (N Y). 2018;4:150–60.

Sevigny J, Chiao P, Bussiere T, Weinreb PH, Williams L, Maier M, et al. The antibody aducanumab reduces Abeta plaques in Alzheimer’s disease. Nature. 2016;537(7618):50–6.

Budd Haeberlein S, O'Gorman J, Chiao P, Bussiere T, von Rosenstiel P, Tian Y, et al. Clinical Development of Aducanumab, an Anti-Abeta Human Monoclonal Antibody Being Investigated for the Treatment of Early Alzheimer’s Disease. J Prev Alzheimers Dis. 2017;4(4):255–63.

Selkoe DJ. Alzheimer disease and aducanumab: adjusting our approach. Nat Rev Neurol. 2019;15(7):365–6.

Ostrowitzki S, Lasser RA, Dorflinger E, Scheltens P, Barkhof F, Nikolcheva T, et al. A phase III randomized trial of gantenerumab in prodromal Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2017;9(1):95.

Bateman RJ, Benzinger TL, Berry S, Clifford DB, Duggan C, Fagan AM, et al. The DIAN-TU Next Generation Alzheimer’s prevention trial: Adaptive design and disease progression model. Alzheimers Dement. 2017;13(1):8–19.

Lilly Announces Topline Results for Solanezumab from the Dominantly Inherited Alzheimer Network Trials Unit (DIAN-TU) Study [press release]. Indianapolis (IN): PRNewswire. Available from: https://www.investor.lilly.com/node/42631/pdf. Accessed 10 March 2020.

Sperling RA, Rentz DM, Johnson KA, Karlawish J, Donohue M, Salmon DP, et al. The A4 study: stopping AD before symptoms begin? Sci Transl Med. 2014;6(228):228fs13.

Eisai and Biogen Announce Positive Topline Results of the Final Analysis for Ban2401 at 18 Months [press release]. Tokyo: Eisai Co., Ltd. Available from: https://www.eisai.com/news/2018/pdf/enews201858pdf.pdf. Accessed 10 Oct 2019.

Logovinsky V, Satlin A, Lai R, Swanson C, Kaplow J, Osswald G, et al. Safety and tolerability of BAN2401--a clinical study in Alzheimer’s disease with a protofibril selective Abeta antibody. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2016;8(1):14.

Sperling RA, Jack CR, Jr., Black SE, Frosch MP, Greenberg SM, Hyman BT, et al. Amyloid-related imaging abnormalities in amyloid-modifying therapeutic trials: recommendations from the Alzheimer’s Association Research Roundtable Workgroup. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7(4):367–85.

Masliah E, Rockenstein E, Veinbergs I, Mallory M, Hashimoto M, Takeda A, et al. Dopaminergic loss and inclusion body formation in alpha-synuclein mice: implications for neurodegenerative disorders. Science. 2000;287(5456):1265–9.

Galvin JE, Lee VM, Trojanowski JQ. Synucleinopathies: clinical and pathological implications. Arch Neurol. 2001;58(2):186–90.

Marras C, Beck JC, Bower JH, Roberts E, Ritz B, Ross GW, et al. Prevalence of Parkinson’s disease across North America. NPJ Parkinsons Dis. 2018;4:21.

Villar-Pique A, Lopes da Fonseca T, Outeiro TF. Structure, function and toxicity of alpha-synuclein: the Bermuda triangle in synucleinopathies. J Neurochem. 2016;139 Suppl 1:240–55.

Huang M, Wang B, Li X, Fu C, Wang C, Kang X. alpha-Synuclein: A Multifunctional Player in Exocytosis, Endocytosis, and Vesicle Recycling. Front Neurosci. 2019;13:28.

Spillantini MG, Crowther RA, Jakes R, Cairns NJ, Lantos PL, Goedert M. Filamentous alpha-synuclein inclusions link multiple system atrophy with Parkinson’s disease and dementia with Lewy bodies. Neurosci Lett. 1998;251(3):205–8.

Wakabayashi K, Yoshimoto M, Tsuji S, Takahashi H. Alpha-synuclein immunoreactivity in glial cytoplasmic inclusions in multiple system atrophy. Neurosci Lett. 1998;249(2–3):180–2.

Ubhi K, Rockenstein E, Mante M, Inglis C, Adame A, Patrick C, et al. Neurodegeneration in a transgenic mouse model of multiple system atrophy is associated with altered expression of oligodendroglial-derived neurotrophic factors. J Neurosci. 2010;30(18):6236–46.

Desplats P, Lee HJ, Bae EJ, Patrick C, Rockenstein E, Crews L, et al. Inclusion formation and neuronal cell death through neuron-to-neuron transmission of alpha-synuclein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106(31):13010–5.

Lee HJ, Suk JE, Bae EJ, Lee SJ. Clearance and deposition of extracellular alpha-synuclein aggregates in microglia. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008;372(3):423–8.

Kisos H, Pukass K, Ben-Hur T, Richter-Landsberg C, Sharon R. Increased neuronal alpha-synuclein pathology associates with its accumulation in oligodendrocytes in mice modeling alpha-synucleinopathies. PLoS One. 2012;7(10):e46817.

Lee HJ, Patel S, Lee SJ. Intravesicular localization and exocytosis of alpha-synuclein and its aggregates. J Neurosci. 2005;25(25):6016–24.

Caplan IF, Maguire-Zeiss KA. Toll-Like Receptor 2 Signaling and Current Approaches for Therapeutic Modulation in Synucleinopathies. Front Pharmacol. 2018;9:417.

Karpowicz RJ, Jr., Trojanowski JQ, Lee VM. Transmission of alpha-synuclein seeds in neurodegenerative disease: recent developments. Lab Invest. 2019;99(7):971–81.

Kim C, Ho DH, Suk JE, You S, Michael S, Kang J, et al. Neuron-released oligomeric alpha-synuclein is an endogenous agonist of TLR2 for paracrine activation of microglia. Nat Commun. 2013;4:1562.

Masliah E, Rockenstein E, Adame A, Alford M, Crews L, Hashimoto M, et al. Effects of alpha-synuclein immunization in a mouse model of Parkinson’s disease. Neuron. 2005;46(6):857–68.

Henderson MX, Covell DJ, Chung CH, Pitkin RM, Sandler RM, Decker SC, et al. Characterization of novel conformation-selective alpha-synuclein antibodies as potential immunotherapeutic agents for Parkinson’s disease. Neurobiol Dis. 2019;136:104712.

Tran HT, Chung CH, Iba M, Zhang B, Trojanowski JQ, Luk KC, et al. Alpha-synuclein immunotherapy blocks uptake and templated propagation of misfolded alpha-synuclein and neurodegeneration. Cell Rep. 2014;7(6):2054–65.

Masliah E, Rockenstein E, Mante M, Crews L, Spencer B, Adame A, et al. Passive immunization reduces behavioral and neuropathological deficits in an alpha-synuclein transgenic model of Lewy body disease. PLoS One. 2011;6(4):e19338.

Bae EJ, Lee HJ, Rockenstein E, Ho DH, Park EB, Yang NY, et al. Antibody-aided clearance of extracellular alpha-synuclein prevents cell-to-cell aggregate transmission. J Neurosci. 2012;32(39):13454–69.

Games D, Valera E, Spencer B, Rockenstein E, Mante M, Adame A, et al. Reducing C-terminal-truncated alpha-synuclein by immunotherapy attenuates neurodegeneration and propagation in Parkinson’s disease-like models. J Neurosci. 2014;34(28):9441–54.

Spencer B, Valera E, Rockenstein E, Overk C, Mante M, Adame A, et al. Anti-alpha-synuclein immunotherapy reduces alpha-synuclein propagation in the axon and degeneration in a combined viral vector and transgenic model of synucleinopathy. Acta Neuropathol Commun. 2017;5(1):7.

Bird RE, Hardman KD, Jacobson JW, Johnson S, Kaufman BM, Lee SM, et al. Single-chain antigen-binding proteins. Science. 1988;242(4877):423–6.