Abstract

Background

The pharmacokinetics of vancomycin, a drug used for the treatment of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), varies between paediatric and adult patients.

Objective

The objective of this study was to assess the pharmacokinetics of vancomycin in preterm neonates and determine the optimum dose regimen.

Methods

This was a randomised double-blind study of preterm neonates admitted to neonatal intensive care units. They all received vancomycin 15 mg/kg every 12 h. Blood was sampled just before administration of the third, sixth and ninth vancomycin dose. Pharmacokinetic parameters were estimated using a Bayesian approach implemented in Monolix 2018R2 software. Covariates assessed included postmenstrual age, current weight, creatinine clearance, albumin, gestational age, body surface area and current age. We used Monte Carlo simulations for dose regimen optimisation targeting area under the concentration–time curve up to 24 h (AUC0–24h) of ≥ 400 mg × h/L.

Results

In total, 19 preterm neonates were enrolled in the study with a median age of 14 (3–58) days. A one-compartment model with linear elimination best described the pharmacokinetics of vancomycin. Volume of distribution and clearance was 0.88 L and 0.1 L/h, respectively, for a typical neonate weighing 1.48 kg. Simulation of the current dose regimen showed that 27.5% of the neonates would achieve the target AUC0–24h of ≥ 400 mg × h/L, and 70.7% of the neonates would achieve it with 12 mg/kg every 8 h.

Conclusion

The majority of the neonates were under dosed. Vancomycin 12 mg/kg should be administered every 8 h over 1 h infusion to improve the likelihood of achieving the AUC0–24h target of ≥ 400 mg × h/L. This target is considered optimal for MRSA infections, where the vancomycin minimum inhibitory concentration is ≤ 1 µg/mL.

Similar content being viewed by others

In preterm neonates, a vancomycin dose of 15 mg/kg every 12 h is inadequate and leads to low plasma exposure in the majority of neonates. |

A vancomycin dose of 12 mg/kg every 8 h, administered as an infusion over 1 h, is optimum in preterm neonates and favours good clinical outcomes. |

1 Introduction

Preterm neonates have impaired or weaker innate immune functions compared with term neonates, which predisposes them to the development of bacterial sepsis during the neonatal period [1]. Sepsis, mainly due to Klebsiella pneumoniae, Staphylococcus aureus, Escherichia coli, Acinetobacter spp. and Pseudomonas spp. infection, is the major cause of morbidity and mortality among neonates in developing countries [2, 3]. In resource-constrained countries, most of these pathogens are resistant to empiric treatment regimens, including ampicillin and gentamicin [2]. The associated adverse outcome of neonatal sepsis, especially in extremely low-birth-weight infants is brain injury, which affects neurodevelopment and growth in early childhood [4].

Vancomycin is recommended for the treatment of methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) in both children and adults [5]. The pharmacokinetics of vancomycin vary more considerably in preterm neonates than in older children or adults. The recommended trough vancomycin concentration (Ctrough) of 15–20 mg/L (or µg/mL) for MRSA infections in children can exceed the target area under the concentration–time curve up to 24 h (AUC0–24h) of 400 mg × h/L in preterm neonates for bacteria with a minimum effective concentration (MIC) of ≤ 1 µg/mL [5, 6]. The AUC0–24h-based dosing of vancomycin is more favourable than Ctrough-based dosing, as the former is safer in terms of development of nephrotoxicity [7]. Moreover, one study found that an AUC-based dosing strategy for vancomycin frequently improved therapeutic target attainment compared with a Ctrough-based dosing strategy [8].

The pharmacokinetics and dose optimisation of vancomycin have been evaluated in neonates [9,10,11,12], but dose recommendations differ considerably among established reference sources [13]. An ideal optimised dose regimen should both mean the majority of the population attains the pharmacodynamic target and that the probability of reaching a toxic pharmacokinetic target is reduced. Therefore, the current study assessed the pharmacokinetics of vancomycin (Aspen-Vancomycin® and Sandoz-Vancocin CP®) and determined the optimal dose regimen in preterm neonates. The secondary objective was to assess whether plasma exposure to these two brands of vancomycin was similar.

2 Methods

2.1 Patient Information and Study Type

This was a randomised double-blind study involving preterm neonates with suspected nosocomial infection who were admitted to the neonatal intensive care units (NICUs) of Netcare Blaauwberg and N1 City hospitals in South Africa. The neonates were randomly allocated to receive either Aspen-Vancomycin® or Sandoz-Vancocin CP®. Each neonate received vancomycin 15 mg/kg every 12 h (twice daily; BID) via peripheral intravenous line over 60 minutes. The physician was blinded to the vancomycin brand and treatment group. The gestational age was determined using early antenatal ultrasound; if this was not available, the new Ballard score was used [14]. Infants were included in the study if they had a corrected postmenstrual age (PMA) of 29–35 weeks and were excluded if they had renal dysfunction or chromosomal abnormalities. We defined renal dysfunction as a lack of or lower than expected serum creatinine decrease in the first week of postnatal life accompanied by risk factors such as low Apgar score, respiratory distress syndrome and ibuprofen-treated patent ductus arteriosus [15]. Neonates needed to have stable renal function for the duration of their vancomycin sampling. Demographic information such as age, sex, birth weight, current weight (at the time of study), gestational age and height were taken from the patient medical records. The information on serum creatinine and serum albumin levels for blood collected on the study day were made available by the hospital laboratory. The estimated glomerular filtration rate was calculated using Eq. (1) [16].

where eGFR is estimated glomerular filtration rate. The C-reactive protein (CRP) test was ordered whenever MRSA was suspected. Meropenem and vancomycin were prescribed when a premature infant showed signs of sepsis.

2.2 Ethics

The University of the Western Cape ethics committee (certificate number: 12/2/21) approved the study. Permission to conduct the study at two Netcare hospitals was obtained from the research department of Netcare hospitals (reference: UNIV-2012-0008). Written informed consent was obtained from the parents of each premature infant enrolled in the study. Strict confidentiality was observed, and the study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki [17].

2.3 Vancomycin Dosing, Blood Sampling and Plasma Assay

Each premature infant received intravenous vancomycin 15 mg/kg infused for 60 minutes BID as per NICU protocol for treatment of suspected MRSA. The blood sample of 0.3–0.5 mL for Ctrough was drawn just before the administration of the third, sixth and ninth doses. Hence, each patient had a maximum of three or at least two blood samples. Blood was collected in BD Mirotrainer SST™ tubes, allowed to clot and then centrifuged to separate blood clots from the serum. Vancomycin plasma concentration was analysed on the Architect™ c1600 system using particle-enhanced turbidimetric inhibition immunoassay (PETINIA). The assay was linear in the range 1.1–100.0 µg/mL. The lowest limit of quantification was 1.1 µg/mL. The accuracy of the assay ranged between 99.3 and 105%. The within-run and between-run precision ranged from 1.1 to 6.1% and from 0.51 to 1.27% of the coefficient of variation, respectively.

2.4 Pharmacokinetic Analysis

The pharmacokinetic analysis was performed using non-linear mixed effects modelling implemented in Monolix 2018R2 software. Since our data set had trough concentrations only, we used a Bayesian approach to estimate pharmacokinetic parameters and their variabilities. We obtained prior information on vancomycin pharmacokinetic parameters in neonates for Bayesian estimation (maximum a posteriori estimation) of population pharmacokinetic parameters from the literature. This prior information was derived from 54 neonates who provided peak and trough vancomycin concentrations [18]. The estimation algorithm used was stochastic approximation expectation maximisation. The Fisher information matrix was computed using stochastic approximation, and the likelihood was calculated by importance sampling.

We used a one-compartment model as a base pharmacokinetic model with the parameters clearance and volume of distribution (Vd). The random variation in the population pharmacokinetic parameters was described by between-subject variability (BSV) with an assumption that parameters were log-normally distributed. We explored the additive, proportional, combined (additive and proportional) and exponential error models to model the residual unexplained variability. The choice of the error model was based on the magnitude of reduction in the objective function (OFV) defined as \(- 2 \times {\text{loglikelihood}}\) and goodness-of-fit plots. The percentage of the relative standard error (RSE) was the measure of precision and was considered when selecting the best error model.

Once we had selected the base model, we investigated possible covariate effects on pharmacokinetic parameters. We performed allometric scaling on disposition parameters using either current weight or body surface area (BSA), where the exponents 0.75 and 1 were fixed on clearance and Vd, respectively [19]. This was done to adjust for the effect of body size. The effect of covariates such as age, PMA, gestational age and sex were tested one at a time. Neonates for whom albumin, serum creatinine and eGFR values were missing were excluded to examine the effect of albumin and eGFR on pharmacokinetic parameters. If no significant effect was observed, the neonates with missing values were included, and then albumin, serum creatinine and eGFR were disregarded in the covariate analysis. A covariate normalised by its median value was retained if it was statistically significant (p ≤ 0.05) using the Wald test, led to a reduction in the BSV and OFV of at least 3.84 points.

2.5 Model Evaluation

We assessed how well the data fit in the final pharmacokinetic model using goodness-of-fit plots such as model-predicted individual concentration versus observed concentration, individual weighted residuals (IWRES) versus time and visual predictive checks (VPC). Additionally, we reported the shrinkage in the population pharmacokinetic parameters. We evaluated the stability and robustness of the model by performing a non-parametric bootstrap resampling procedure in Monolix with the aid of Rsmlx (R Speaks ‘Monolix’) R package (http://rsmlx.webpopix.org). The median values from the 500 bootstrap runs were compared with the median (typical) values of the estimated pharmacokinetic parameters.

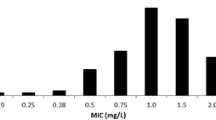

2.6 Assessment of the Current Dose Regimen and Optimisation by Monte Carlo Simulation

A pharmacodynamic index ratio (AUC0–24h/MIC) of ≥ 400 is recommended as a target to achieve clinical effectiveness with vancomycin in MRSA with an MIC of 1 µg/mL [20], so we aimed for an AUC0–24h target of ≥ 400 mg × h/L. We assessed the current dose regimen of vancomycin 15 mg/kg BID by performing a Monte Carlo simulation of AUC0–24h and Ctrough of 1000 neonates at steady state using Simulx (Antony, France: Lixoft SAS, 2018). We recorded the percentage of neonates who achieved AUC0–24h ≥ 400 mg × h/L.

Monte Carlo simulations of 1000 neonates were repeated using different plausible vancomycin doses and dosing intervals. This ensured the identification of the optimal dose regimen that would result in most of the neonates reaching the target AUC0–24h of ≥ 400 mg × h/L. Identifying the Ctrough associated with AUC0–24h ≥ 400 mg × h/L was important. Therefore, we determined the interquartile range of Ctroughs from the optimised dose regimen that corresponded to AUC0–24h ≥ 400 mg × h/L. We then compared the current dose regimen with the optimised regimen in terms of the percentage of neonates who achieved the desired target AUC0–24h.

2.7 Assessment of Plasma Exposure of Vancomycin in the Two Treatment Groups

The plasma trough concentrations for neonates assigned to Aspen-Vancomycin® or Sandoz-Vancocin CP® were compared using the Mann–Whitney U test. The comparison was carried out across three sampling time points (just before the third, sixth and ninth doses) and at all sampling time points.

3 Results

In total, 19 preterm neonates were enrolled in the study. They provided a total of 45 plasma concentration–time points for vancomycin. Seven neonates had respiratory distress syndrome; two had jaundice and one had necrotising enterocolitis. Table 1 summarizes the demographic information, and Fig. 1 shows the observed Ctrough–time profile.

3.1 Pharmacokinetic Model

The selected base model was a one-compartment pharmacokinetic model with parameters Vd and clearance. The exponential error model best described the residual unexplained variability on pharmacokinetic parameters. Current weight was a better descriptor of body size than was BSA. Allometric scaling by fixing the exponents of Vd and clearance to 1 and 0.75, respectively, using current weight improved the model (∆OFV, − 6.08). This explained 10.7% and 7.1% of the variation in Vd and clearance, respectively. Estimation of the allometric exponents did not yield better results than fixing because parameters were not estimated with good precision. The covariates albumin, creatinine clearance, serum creatinine, PMA, age, sex and gestational age had no significant effect on Vd or clearance. The parameters of the final pharmacokinetic model are shown in Table 2. The RSE for the BSV in clearance was > 50% (63.4%), and this implied that the value of BSV in clearance was not estimated with good precision. However, the rest of the pharmacokinetic parameters were estimated with good precision. The individual models for clearance and Vd of an ith subject are represented by Eqs. (2) and (3), respectively.

3.2 Model Evaluation

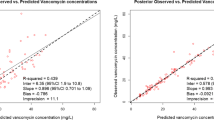

The goodness-of-fit plots (Fig. 2) showed no trend in the splines of the plots for IWRES versus time or for IWRES versus predicted concentration. Furthermore, individual predicted concentrations were similar to the observed concentrations as the regression spline was in agreement with the line of unity. This indicated that the data fit well to the model. The VPC in Fig. 3 shows that the model generated Ctrough well, although a higher variation in the 95th percentile was observed. The results of the 500 bootstrap replicates are presented in Table 2. The population pharmacokinetic parameter estimates of the final model were similar to the bootstrap median parameters, which indicated that the final population pharmacokinetic model was stable and the parameters were robust.

3.3 Assessment of the Current Dose Regimen and Optimisation

Monte Carlo simulation of 1000 neonates receiving the current vancomycin dose of 15 mg/kg BID indicated that 27.5% of them would achieve the target AUC0–24h of ≥ 400 mg × h/L. Hence, the current dose regimen was not optimal, as < 50% of the neonates achieved the recommended target. The optimal dose regimen, found after trying several doses and dosing intervals, was 12 mg/kg every 8 h (three times daily; TID). This dose regimen led to 70.7% of the neonates achieving the recommended target AUC0–24h of ≥ 400 mg × h/L. Figure 4 compares the distributions of the current and optimised vancomycin dose regimens and shows their corresponding Ctrough.

The exposure (AUC0-24h and Cmax) profiles for the current and optimised vancomycin dose regimen. A dotted line on the AUC0-24h axis represents the target AUC0-24h; the two dotted lines on the Cmax axis represent the upper and lower quartiles values of Cmax associated with AUC0-24h ≥400 mg × h/L. AUC0-24h area under the concentration–time curve up to 24 h, Cmax peak plasma concentration

The median (interquartile range [IQR]) Ctrough for neonates who achieved AUC0–24h ≥ 400 mg × h/L was 11 (8–14) µg/mL. The median (IQR) AUC0–24h and Ctrough for the current dose regimen was 366 (326–406) mg × h/L and 5.88 (3.3–8.4) µg/mL, respectively. Meanwhile, for the optimised dose regimen, the AUC0–24h and Ctrough were 440 (391–491) mg × h/L and 9.4 (6.6–12.6) µg/mL, respectively. The percentage of neonates with Ctrough > 20 µg/mL was 0.5.

3.4 Comparison of Vancomycin Plasma Exposure in Two Treatment Groups

At all sampling time points (just before administration of the third, sixth and ninth doses), vancomycin plasma concentration was significantly higher with Aspen-Vancomycin® than with Sandoz-Vancocin CP® (p = 0.015) (Table 3). However, vancomycin concentrations measured at specific time points (23.8, 59.8 and 95.8 h) were similar for Aspen-Vancomycin® and Sandoz-Vancocin CP® (p > 0.05).

4 Discussion

In this study of preterm neonates, a one-compartment pharmacokinetic model with linear elimination best described the pharmacokinetics of vancomycin. It was necessary to use a Bayesian approach to estimate the pharmacokinetic parameters as our data set included only Ctrough concentrations. A Bayesian approach allow the estimation of pharmacokinetic parameters based on the data but also consider prior information from the literature. Hence, the pharmacokinetic parameters estimated in the current study were comparable with those reported in a similar population of neonates with ranges of 0.58–1.19 L and 0.054–0.07 L/h for Vd and clearance, respectively [9, 21,22,23]. We observed a high variation in the Vd (54%), which could not be explained by covariates tested. Other studies involving paediatric populations reported similarly high variations in Vd (43 and 77%) [24, 25]. In contrast, some studies in neonatal populations reported low variations in vancomycin Vd (32 and 29.4%) [9, 18]. Studies [26,27,28] have shown sepsis to be associated with high values of Vd due to the increase in capillary permeability that results in interstitial oedema. This may warrant administration of higher doses in septic patients to achieve the target concentration. The high variation in the Vd of the current study could have been due to differences in the degree of sepsis that the neonates had during the treatment period. Inflammatory markers such as CRP and erythrocyte sedimentation rate [29] could have explained this variation in Vd, but we did not have these markers in our data. In some studies [9, 21, 30], PMA and serum creatinine were statistically significant covariates that explained the BSV in vancomycin clearance. The non-statistically significant effect of PMA and serum creatinine on clearance in the current study could be due to the small sample size and narrow variations in PMA and serum creatinine values. Nevertheless, our findings are consistent with those of Germovsek et al. [18], who reported that serum creatinine had no significant effect on vancomycin clearance.

The assessment of the current vancomycin dose regimen of 15 mg/kg BID, using Monte Carlo simulation, indicated that only 27.5% of the neonates would achieve the recommended target AUC0–24h of ≥ 400 mg × h/L for an MIC of 1 µg/mL. Similarly, other studies [21, 23, 24] reported that a small percentage (12.7–41%) of neonates attaining the vancomycin target concentration/AUC0–24h with vancomycin 10–15 mg/kg every 6 h, TID or BID. The clinical consequences of low vancomycin exposure are prolonged duration of bacteraemia [31] and development of drug-resistant bacterial strains [32].

An optimal dose regimen should increase the probability of most patients achieving the target pharmacodynamic index with no or few patients in the pharmacokinetic toxic range. We determined a vancomycin dose of 12 mg/kg TID to be optimal in this population of neonates with sepsis due to suspected MRSA infection. This optimised dose regimen increased the percentage of neonates attaining target AUC0–24h from 27.7 to 70.7%. The Ctroughs associated with the AUC0–24h of ≥ 400 mg × h/L ranged between 8 and 14 µg/mL. This is consistent with values reported in previous studies, where vancomycin AUC0–24h ≥ 400 mg × h/L was associated with a Ctrough range of 7–10 µg/mL [33, 34].

Overall, plasma exposure to vancomycin differed between the treatment groups receiving different brands of vancomycin. This clarifies that variations in vancomycin plasma exposure in preterm neonates may be attributable to the use of different brands of vancomycin commonly used at the hospital.

Our study has some limitations. The sample was small and from a homogenous population. Hence, the likelihood of finding significant covariates on the pharmacokinetic parameters was low. We could only measure trough concentrations of vancomycin, and no blood was drawn during the distribution phase, which could result in estimations of Vd with low precision. We also reported low variations in clearance (4 vs. 32%), which was lower than that reported in the literature [18] and could have underestimated the variations in simulated AUC. However, we circumvented this problem by using a Bayesian approach (a priori information) to estimate the pharmacokinetic parameters. Additionally, prior information on vancomycin pharmacokinetics used in Bayesian estimations of pharmacokinetic parameters in our study was derived from the data that had both peak and trough concentrations. The number of neonates was also greater than in our study [18].

5 Conclusions

The current vancomycin dose regimen in preterm neonatal populations is inappropriate, as most neonates are likely to be under dosed. Based on Monte Carlo simulation, we propose a vancomycin optimal dose regimen of 12 mg/kg TID as an infusion lasting for 60 min in neonates meeting the inclusion criteria of the current study. Additionally, the proposed regimen is unlikely to result in Ctroughs of > 20 µg/mL, thereby minimising the likelihood of overexposure and the risk of nephrotoxicity.

References

Tissieres P, Ochoda A, Dunn-Siegrist I, Drifte G, Morales M, Pfister R, et al. Innate immune deficiency of extremely premature neonates can be reversed by interferon-gamma. PLoS One. 2012;7:e32863.

Zaidi AKM, Huskins WC, Thaver D, Bhutta ZA, Abbas Z, Goldmann DA. Hospital-acquired neonatal infections in developing countries. Lancet. 2005;365:1175–88.

Kayange N, Kamugisha E, Mwizamholya DL, Jeremiah S, Mshana SE. Predictors of positive blood culture and deaths among neonates with suspected neonatal sepsis in a tertiary hospital, Mwanza-Tanzania. BMC Pediatr. 2010;10:39.

Stoll BJ, Hansen NI, Adams-Chapman I, Fanaroff AA, Hintz SR, Vohr B, et al. Neurodevelopmental and growth impairment among extremely low-birth-weight infants with neonatal infection. JAMA. 2004;292:2357–65.

Liu C, Bayer A, Cosgrove SE, Daum RS, Fridkin SK, Gorwitz RJ, et al. Clinical practice guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America for the treatment of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections in adults and children. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52:e18–55.

Alsultan A, Abouelkheir M, Alqahtani S, Aljabri A, Somily AM, Alsubaie S, et al. Vancomycin monitoring in pediatric patients. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2018;37:880–5.

Finch NA, Zasowski EJ, Murray KP, Mynatt RP, Zhao JJ, Yost R, et al. A quasi-experiment to study the impact of vancomycin area under the concentration-time curve-guided dosing on vancomycin-associated nephrotoxicity. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2017;61:e01293–17.

Meng L, Wong T, Huang S, Mui E, Nguyen V, Espinosa G, et al. Conversion from vancomycin trough concentration-guided dosing to area under the curve-guided dosing using two sample measurements in adults: implementation at an Academic Medical Center. Pharmacotherapy. 2019;39:433–42.

Kato H, Hagihara M, Nishiyama N, Koizumi Y, Mikamo H, Matsuura K, et al. Assessment of optimal initial dosing regimen with vancomycin pharmacokinetics model in very low birth weight neonates. J Infect Chemother. 2017;23:154–60.

Marques-Minana MR, Saadeddin A, Peris JE. Population pharmacokinetic analysis of vancomycin in neonates. A new proposal of initial dosage guideline. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2010;70:713–20.

Cies JJ, Moore WS, Nichols K, Knoderer CA, Carella DM, Chopra A. Population pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamic target attainment of vancomycin in neonates on extracorporeal life support. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2017;18:977–85.

James A, Koren G, Milliken J, Soldin S, Prober C. Vancomycin pharmacokinetics and dose recommendations for preterm infants. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1987;31:52–4.

Liem TBY, Slob EMA, Termote JUM, Wolfs TFW, Egberts ACG, Rademaker CMA. Comparison of antibiotic dosing recommendations for neonatal sepsis from established reference sources. Int J Clin Pharm. 2018;40:436–43.

Ballard J, Khoury J, Wedig K, Wang L, Eilers-Walsman B, Lipp R. New Ballard Score, expanded to include extremely premature infants. J Pediatr. 1991;119:417–23.

Walker MW, Clark RH, Spitzer AR. Elevation in plasma creatinine and renal failure in premature neonates without major anomalies: terminology, occurrence and factors associated with increased risk. J Perinatol. 2011;31:199–205.

Brion LP, Fleischman AR, McCarton C, Schwartz GJ. A simple estimate of glomerular filtration rate in low birth weight infants during the first year of life: noninvasive assessment of body composition and growth. J Pediatr. 1986;109:698–707.

General Assembly of the World Medical Association. World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. J Am Coll Dent. 2014;81:14–8.

Germovsek E, Osborne L, Gunaratnam F, Lounis SA, Busquets FB, Standing JF, et al. Development and external evaluation of a population pharmacokinetic model for continuous and intermittent administration of vancomycin in neonates and infants using prospectively collected data. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2019;74:1003–11.

Anderson BJ, Holford NHG. Mechanistic basis of using body size and maturation to predict clearance in humans. Drug Metab Pharmacokinet. 2009;24:25–36.

Rybak M, Lomaestro B, Rotschafer JC, Moellering R Jr, Craig W, Billeter M, et al. Therapeutic monitoring of vancomycin in adult patients: a consensus review of the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists, the Infectious Diseases Society of America, and the Society of Infectious Diseases Pharmacists. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2009;66:82–98.

Chen Y, Wu D, Dong M, Zhu Y, Lu J, Li X, et al. Population pharmacokinetics of vancomycin and AUC-guided dosing in Chinese neonates and young infants. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2018;74:921–30.

Mehrotra N, Tang L, Phelps SJ, Meibohm B. Evaluation of vancomycin dosing regimens in preterm and term neonates using Monte Carlo simulations. Pharmacotherapy. 2012;32:408–19.

Zhao W, Lopez E, Biran V, Durrmeyer X, Fakhoury M, Jacqz-Aigrain E. Vancomycin continuous infusion in neonates: dosing optimisation and therapeutic drug monitoring. Arch Dis Child. 2013;98:449–53.

Zhao W, Zhang D, Fakhoury M, Fahd M, Duquesne F, Storme T, et al. Population pharmacokinetics and dosing optimization of vancomycin in children with malignant hematological disease. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2014;58:3191–9.

Lamarre P, Lebel D, Ducharme MP. A population pharmacokinetic model for vancomycin in pediatric patients and its predictive value in a naive population. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2000;44:278–82.

Marik P. Aminoglycoside volume of distribution and illness severity in critically ill septic patients. Anaesth Intensive Care. 1993;21:172–3.

Kieft H, Hoepelman A, Knupp C, Van Dijk A, Branger J, Struyvenberg A, et al. Pharmacokinetics of cefepime in patients with the sepsis syndrome. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1993;32(suppl_B):117–22.

Tang G, Tang J, Lin B, Kong C, Lee T. Factors affecting gentamicin pharmacokinetics in septic patients. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 1999;43:726–30.

Harrison M. Erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein. Aust Prescr. 2015;38:93–4.

Stockmann C, Hersh AL, Roberts JK, Bhongsatiern J, Korgenski EK, Spigarelli MG, et al. Predictive performance of a vancomycin population pharmacokinetic model in neonates. Infect Dis Ther. 2015;4:187–98.

Hsu AJ, Hamdy RF, Huang Y, Olson JA, Ghobrial S, Gerber JS, et al. Association between vancomycin trough concentrations and duration of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia in children. J Pediatr Infect Dis Soc. 2018;7:338–41.

Drlica K. The mutant selection window and antimicrobial resistance. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2003;52:11–7.

Le J, Bradley JS, Murray W, Romanowski GL, Tran TT, Nguyen N, et al. Improved vancomycin dosing in children using area under the curve exposure. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2013;32:e155–63.

Frymoyer A, Guglielmo BJ, Hersh AL. Desired vancomycin trough serum concentration for treating invasive methicillin-resistant Staphylococcal infections. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2013;32:1077–9.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Netcare Ltd for providing access to conduct the study at the two Netcare hospitals. We thank the parents who gave consent to include their infants in the study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Mwila Mulubwa analysed/interpreted the data and drafted the manuscript. Heletje Aletta Griesel conceived the idea, wrote the study protocol and implemented the study. Pierre Mugabo designed and supervised the study. Ricky Dippenaar recruited patients and conducted blood sample collection for vancomycin and biological tests. Lizelle van Wyk coordinated blood sample collection for vancomycin plasma levels and biological tests. All authors reviewed and approved the final draft.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

No specific funding was received for the conduct of this study or preperation of this manuscript.

Conflicts of interest

Mwila Mulubwa, Heletje Aletta Griesel, Pierre Mugabo, Ricky Dippenaar, and Lizelle van Wyk have no conflicts of interest that are directly relevant to the content of this article.

Ethical approval

The ethics committee of the University of the Western Cape approved the study (certificate number: 12/2/21). Permission was sought from the research department of Netcare hospital (reference: UNIV-2012-0008) to conduct the study.

Informed consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the parents of each premature infant before enrolment in the study. Strict confidentiality was observed, and the study was carried out in accordance with the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. The parents had the right to withdraw their infants from the study at any time without giving a reason.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mulubwa, M., Griesel, H.A., Mugabo, P. et al. Assessment of Vancomycin Pharmacokinetics and Dose Regimen Optimisation in Preterm Neonates. Drugs R D 20, 105–113 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40268-020-00302-7

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40268-020-00302-7