Abstract

Achieving publications in high-impact journals is a major cornerstone for academic careers in the US and elsewhere in the world. However, apart from novel insights and relevant contributions to the field, there are expectations of editors and reviewers regarding the structure and language of manuscripts that prospective contributors have to adhere to. As these expectations are mostly communicated using best-practice examples, especially international researchers might often wonder how to implement them in their manuscripts. Applying an applied linguistics model to 60 papers that were published in US-based and Indian management journals we derive evidence-based advice for the writing of introductions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Management researchers all across the world aspire to publish their research in the most renowned journals of the field, such as Academy of Management Journal. Apart from the prestige of such successful publications, researchers hope to reach a wide readership and influence their community with their ideas and findings (Canagarajah 2002; Clark et al. 2017; Judge et al. 2007). Even though the peer-review process tries to ensure that every submission is evaluated on the same criteria, achieving a publication of one’s own research is remarkable still as rejection rates of 90% and more are common amongst the high impact management journals (APA 2018; George 2016). Therefore, many management researchers struggle with academic writing, perceiving the reviewing process to be difficult and not transparent (e.g., Hollenbeck 2008).

This is even more so for the case for international authors who are already struggle with writing in English on top of being vaguely aware of the implicit expectations from the editors and the reviewers (Bajwa et al. 2016; Horn 2017; Pudelko and Tenzer 2018). However, as editors and reviewers have increased their efforts to accommodate more international submissions in their journals, also have increasingly realized that they need to communicate their expectations more explicitly in order to increase the chances (e.g. Eden and Rynes 2003). Thus, for prospective authors who aim at increasing the likelihood of getting past a desk rejection and evoke a positive outset for reviewers, it is necessary to not only focus on the research questions but also on the first impression the presentation of their thoughts and ideas will have on editors and reviewers (Barney 2018; George 2012).

The introduction section is especially perceived to have a significant impact on the first impression of a manuscript and thus has gained a lot of attention (Ahlstrom et al. 2013; Barney 2018; George 2012; Jacobsson and Hällgren 2014; Voordeckers et al. 2014). Successful management researchers seem to spend almost a quarter of their total writing time on the comparatively short introduction and hence use it to attract the readers’ interest (Grant and Pollock 2011). Meanwhile, editors of high impact management journals have tried to use best practice examples of successful researchers in order to illustrate what constitutes an exceptional introduction (e.g., Webster and Watson 2002). However, as these best practices are exceptionally well written they do not necessarily represent the usual expectations of an introduction and at the same time are not evidence-based (Bajwa et al. 2016).

In order to provide prospective authors with recommendations that reflect the expectations of editors and reviewers in the field more appropriately it is important to tap into knowledge from a research field that have been dedicated to understanding how language related aspects are usually incorporated in research communication: applied linguistics. Therefore, we utilize Swales (2004) Create-A-Research-Space model (CARS) of introductions and analyze the rhetorical components of introductions in US-based journals. By comparing these introductions with introductions from non-US journals, we aim to shed light on expectations of editors and reviewers and develop evidence-based recommendations for writing an introduction.

Theoretical background

Management research

Aspiring researchers are under increasing pressure to enhance their efforts to communicate their research findings in scientific journals and for several decades now follow the motto “Publish or Perish” (Harzing 2007). However, as the space in high impact journals is confined and more and more researchers are trying to achieve a publication (APA 2018; Rynes et al. 2005), having only a good research idea is most likely not going to be good enough to pass the first barrier in research communication, which is the review process (Colquitt and George 2011). Hence, prospective authors or authors whose manuscripts were rejected seek to have better understanding on the decision processes of editors and reviewers (Ashford 2013; Bono and McNamara 2011; Rynes et al. 2005; Webster and Watson 2002).

For this purpose it is helpful to perceive the communication of research as a form of conversation with peers of which the review process is just the first part that ideally helps to improve one’s thoughts and ideas (Huff 1999; Sparrowe and Mayer 2011). Editors and reviewers want to see convincing arguments that are put forward by an author, and as with regular conversations there are certain expectations on how a persuading argument is put forward (Ashford 2013). Authors who adhere to certain patterns of argumentation and presentation decrease the risk of encountering reactance and increase the likelihood of a positive evaluation of their work (Sandberg and Alvesson 2011; Sparrowe and Mayer 2011). However, some of these rules or expectations can be very explicit and comparatively easy to follow (e.g., citation styles), whereas others can be very implicit (e.g., the metastructure of a paper) and thus difficult to get a hold of (George 2012).

Especially expectations regarding language and rhetorical aspects are often very implicit, yet they seem to play an important role in influencing the impression editors and reviewers form of a manuscript (Eden and Rynes 2003; Kelemen and Bansal 2002; Kwan 2013). For example, if a study is not presented or framed according to readers’ expectations, it might be rejected as the arguments and thoughts are perceived to be not convincing enough in the context of the particular frame an author chose to select (George 2012; Hollenbeck 2008). Or if authors are not cautious enough when communicating their arguments, editors and reviewers might perceive some arguments as being too strong and therefore oppose the authors’ views (e.g. Bajwa et al. 2016). To reduce the likelihood of encountering these kinds of objections, in the US, aspiring researchers are sensitized to the intricacies of academic writing early on in their careers as a part of their postgraduate training (Golde and Dore 2001).

As the introduction has a significant influence on the initial perception of a manuscript it should play an important role during the writing of a manuscript (Swales 2004). Editors and reviewers stress that a well written introduction raises interest and the likelihood of having a positive attitude while reading the rest of the manuscript, whereas a less intriguing introduction might raise reservations (Grant and Pollock 2011). Furthermore, as the introduction sections in management journals usually represent a brief summary of the reasons why the study is necessary and how it will advance the understanding of certain phenomena, it is a decisive factor for potential readers when deciding whether to continue or stop reading (cf. Barney 2018; Bartunek et al. 2006; Rynes et al. 2005).

Given the stakes, it might come as no surprise that experienced and successful researchers perceive writing an introduction as one of the most difficult and time-consuming parts of academic writing. For example, Grant and Pollock (2011) surveyed the 22 “Best Article Award” winners of the Academy of Management Journal and found that they used approximately 24% of the their total writing time of an article for the introduction, even though, they believe, it only constitutes approximately 10% of the total length of a paper. Furthermore, as the introduction is a very condensed depiction of the reasons for conducting the study, successful researchers tend to rewrite their introductions an average of ten times to assure that it best represents the study itself.

Hence, understanding what editors and reviewers might believe to be integral parts of a good introduction for a research article is of great importance (George 2015). As these expectations vary from research field to research field it is necessary to account for the customs within a particular research field (Samraj 2002). In the field of management research, successful researchers have published editorials in which they describe their personal experiences and using best-practice examples develop recommendations for the writing of introductions (e.g., Barney 2018; Grant and Pollock 2011; Webster and Watson 2002). While best practices might do a good job in giving aspiring researchers ideas about what very successful researchers have done, best practices are limited in their generalizability (Nicoll and Harrison 2003; Starkey and Madan 2001).

Understanding these best-practice examples is even more difficult for non-US researchers, who already struggle with English not being their first language and thus are affected by language related issues of the academic discourse the most (Cadman 1997). Compared to aspiring US researchers, non-US researchers have to put in more effort to learn the intricacies of academic writing in English as English is the de facto lingua franca of science and non-native speakers of English have to learn these intricacies in addition to the English language itself (Holmes 1988; Horn 2017; Hwang 2005; Mu and Zhang 2018). Hence, best-practice examples might create the impression that it is necessary to create an extraordinary introduction, whereas for non-US authors the first step might rather be to better understand the very basic expectations (cf. Kwan 2013).

Furthermore, as the visibility of research from outside of the US in these journals is very low (Baruch 2001; Podsakoff et al. 2008), non-US researchers are likely to have comparatively fewer possibilities to acquire the rather implicit aspects of academic writing through conversations with mentors or other peers who have experience in publishing in high impact journals (George 2012). For example, in Personnel Psychology, approximately 82% of publications are attributed to researchers affiliated with US institutions (Cascio and Aguinis 2008). Furthermore, there is a huge discrepancy between the number of non-US members of professional organizations, such as the Academy of Management, and the proportion of contributors, editors and reviewers from non-US countries (Academy of Management 2019; Burgess and Shaw 2010). Hence, hitting the right strings in academic writing, which is already herculean task for US authors (e.g. Locke and Golden-Biddle 1997), may be even more challenging for non-US researchers (e.g., Dueñas 2012).

Therefore, to further the understanding of editors’ and reviewers’ expectations and create actionable and evidence-based advice for US and non-US researchers alike, it makes sense to utilize concepts from a research field that is devoted to understanding language related aspects in academic writing: applied linguistics. The field of applied linguistics tries to understand the practical problems of everyday language use (including language in academic settings) and goes beyond descriptions of how language should be used towards data-driven theories of how language is currently being used in specific contexts (Davies and Elder 2004).

Evidence-based advice for writing introductions

To analyze what a typical introduction in a particular field looks like, applied linguists have developed the Create-A-Research-Space (CARS) model (Swales 1981, 1990, 2004). Over the last years it has established itself as the dominating approach to rhetorically analyze research article introductions and provides a detailed classification of its contents (e.g., Fakhri 2004; Loi 2010; Samraj 2002; Sheldon 2011; Swales 1981, 1990; Swales and Najjar 1987). According to the CARS model of Swales (2004), a research article introduction can be separated into three discoursal or rhetorical units, called moves: (a) establishing a territory, (b) establishing a niche, and (c) occupying the niche. Each of the moves is comprised of smaller units, the so-called steps, with each move having at least one mandatory step that applied linguists expect authors to use in the introduction. Furthermore, depending on the research field and the expectations of editors and reviewers, some moves also provide the opportunity to use optional steps (see Table 1).

Establishing a territory

The first move aims at providing an introduction to the general topic of the study, with the author trying to convince the audience of the importance of the field of study itself and bringing aboard a broad readership. According to Swales’ (2004) model in this move there is only one step that has to be incorporated, which he dubbed “topic generalizations of increasing specificity”. Furthermore, a key expectation of readers from this move is that references are provided to support the claims of importance.

Establishing a niche

The second move aims at providing an introduction to the more specific research debate that the authors are trying to engage in. After Move 1 establishes the broad topic, authors have to explain the reasons why their choice of a particular sub-topic is important to look at. There seem to be two possible ways in which this can be achieved: Either by “indicating a gap” (Move 2, Step 1A), i.e., by explaining that previous research might have overlooked an important aspect, or by “adding to what is known” (Move 2, Step 1B), i.e., adding a new perspective might enhance our understanding of a certain concept, model, or theory. Additionally, yet optional, it is also possible to “present positive justification” (Move 2, Step 2) if the need for addressing a certain gap or the benefit of new knowledge does not seem to be self-evident.

Occupying a niche

After awareness for the necessity of and interest for studying the particular sub-topic have been stated in Move 2, Move 3 follows by explaining the specific research question that the authors chose to address the research niche with that was indicated in Move 2. Swales (2004) calls this obligatory step “Announcing present research descriptively and/or purposively” and leaves room for more optional steps that can be incorporated to enhance the rhetorical structure of this move (for details see Table 1). It is important to note here that in this move own thoughts are deduced from research that was presented before, so in general there is no need to use references in this step.

As can be seen from the explanation of the moves and steps, Swales expects there to be a typical order of the moves: Move 1 is followed by Move 2, which is then followed by Move 3 (Swales 1990). Alternatively, some studies (e.g., Swales and Najjar 1987) also found that in frequent cases the explanation of the own research niche (i.e., Move 3) is presented first, after which more context is provided (Move 1 and 2) and the research question is elaborated again (Move 3), hence a common structural order can also be Move (3-)1-2-3 (Swales 2004). The refinement of the CARS model has attracted a lot of research that has confirmed its wide applicability across research areas and thus its appropriateness to analyze research articles’ introductions (e.g., Belcher 2009; Hirano 2009; Milagros del Saz Rubio Milagros del Saz Rubio 2011; Pho 2008; Sheldon 2011).

Although the move structure of introductions seems to be similar across research disciplines, what constitutes an introduction across research fields still varies greatly (e.g., Samraj 2002). When Swales refers to the introduction, it is meant to be the theory section of a paper, as indicated by the IMRAD (introduction-methods-results-and-discussion) model (see Day 1989). However, in the field of management an introduction usually refers to the first few paragraphs before the theoretical background (Grant and Pollock 2011). Although the CARS model has been proven to be an empirically valid instrument for the analysis of introductions in a variety of research fields and has been used to offer detailed insights into the use of rhetorical units in research articles (e.g., Loi 2010), only a few studies have looked into the composition of introductions in the field of management using the CARS model using small datasets from multiple decades (e.g., Lim 2012). Swales (2015) assured us that the CARS model should be applicable to what management researchers refer to as introductions as well and hence, to better understand the expectations of editors and reviewers, we apply the CARS model to management randomly selected research articles published in US-based journals in the same year and address the research question:

Research question: What are the characteristics of US-based management research article introductions?

Moreover, applied linguists assume that within specific academic communities (e.g., management researchers) socially acceptable writing conventions are established implicitly or explicitly (Hyland 2002). These writing conventions make it plausible to assume that an analysis of introductions in management journals from the US with the CARS model would likely illuminate rhetorical similarities (see Belcher 2009). At the same time, if the low visibility of research from non-US countries can be assumed to be related to non-US authors’ violation of editors’ and reviewers’ expectations, the analysis of research articles that are from a country with a low visibility in management research should illustrate significant differences in the number of moves, the order of the moves, the total number of steps, and the number of citations that are used in the introductory sections compared to US journal articles. For the purpose of our study, we decided to compare US-based management journals with management journals from India, hence, our hypotheses are:

H1:

Introductions of research articles in US-based management journals should contain significantly more moves and steps than in Indian research articles.

H2:

Introductions of research articles in US based management journals should contain significantly more citations than Indian research articles.

H3:

Introductions of research articles in US-based management journals should contain the suggested (3-)1-2-3 move order more often than in Indian research articles.

Method

Sample

As we wanted to assure that we were not only assessing the expectations of editors and reviewers of one particular journal and wanted to cover a range of subjects and areas we decided to use multiple journals for our analysis. Thus we selected the Academy of Management Journal, the Journal of Management, and Human Resource Management for further analysis. Furthermore, following the arguments of Bajwa et al. (2016), we selected India as a country with a low visibility in management research and included Management and Labour Studies, Vision: The Journal of Business Perspective and the Indian Journal of Industrial Relations in our analysis.

In order to reduce any confounding effect the type of study might have had on the introduction (Swales 2004), we excluded theoretical papers and case studies from our sample and limited our analysis to empirical research articles only (i.e., research articles that analyzed quantitative data). Hence, as done in other studies, we randomly selected 10 articles per journal (i.e., 30 journals per country), resulting in a total sample of 60 articles (e.g., Chang and Kuo 2011; Sheldon 2011). We were aware that a limited sample might restrict the generalizability, however selecting multiple journals and having a total of 60 articles should be sufficient for indications of writing tendencies (see Lim 2012; Sheldon 2011).

Procedure

We followed the steps for conducting a move analysis recommended by Biber (2007, p. 34): First, we created a coding table on the basis of Swales’ (2004) CARS model (see Table 1). Next, two raters coded two articles based on the coding table and discussed similarities and differences in their ratings to achieve a mutual understanding of the rhetorical structures. Afterwards, the raters decided to proceed in the following way: First, they read the article’s abstract, to understand its main topic and then continued reading its introduction. If after this first reading the authors did not have any reservations, they went through the introduction again, identified all moves and steps and marked them in the files using the qualitative analysis software MaxQDA (Verbi GmbH 2013). If raters were hesitant to identify moves and steps, they read the discussion section and then went back to identify the moves and steps in the introduction. Last, in each move and step we checked whether citations were used and counted the total number of citations.

To assure the quality of the coding, both raters each rated a randomly chosen sample of 10 articles, achieving an acceptable interrater reliability of Krippendorff’s α = .75 for all steps, and a good interrater reliability of Krippendorff’s α = .81 when excluding optional steps (Hayes and Krippendorff 2007; Krippendorff 2012). Hence, as the quality of the coding proved to be good the remaining 50 articles were randomly assigned to both raters for further coding.

Results

Descriptive analysis

The length of articles, t(58) = 8.78, p < .001, d = 2.26, and introductions, t(58) = 5.37, p < .001, d = 1.38, differed significantly across countries with the US research articles MUS = 86,370, SDUS = 25,556, MIndia = 42,365, SDIndia = 10,102, and introductions, MUS = 5330, SDUS = 1998, MIndia = 2406, SDIndia = 2214, being significantly longer than the Indian (for details see Table 2). In US-based journals the introduction comprised 6.55% of the total articles’ length, whereas in India it comprised 5.60% of the total articles’ length.

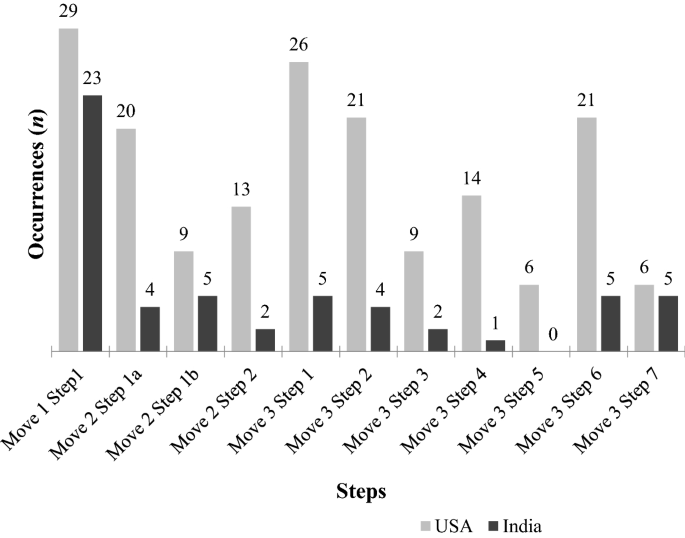

Research question

Addressing our research question, our data shows that Move 1, Move 2, and Move 3 occur in 96.67% of the US articles. More specifically, within Move 2 indicating a gap (Move 2 Step 1A) seems to be used in 66.67% of the cases, whereas adding to what is known (Move 2 Step 1B) was only used in 30.00% of the cases (see Fig. 1). Furthermore 43.33% of the articles positive justification was presented (Move 2 Step 2). Within Move 3, the present research was described descriptively (Move 3 Step 1) in 96.67% of the articles; research questions or hypotheses (Move 3 Step 2) and stating the value of the research were presented in 70.00% of the cases, and in 46.67% of the cases methods were summarized (Move 3 Step 4) (Table 3).

Test of hypotheses

We tested our first hypothesis (H1) that US journals should have significantly more moves and steps than Indian journals using t tests. For both, moves, t(58) = 6.33, p < .001, d = 1.66, and steps, t(58) = 8.41, p < .001, d = 2.17, we found significant differences. Interestingly, in 93.33% of the US articles all 3 Moves as defined by Swales (2004) could be found, whereas for India this was only the case for 10.00% of the articles. Furthermore, on average, an introduction had MUS = 5.80 steps, SDUS = 1.83 in the US and MIndia = 1.87 steps, SDIndia = 1.80 in India, indicating that introductions in US journals were not only longer but rhetorically more elaborate (see Table 4).

Second, we analyzed the usage of citations in the introduction (H2): 96.67% of the introductions in the US journals compared to 60.00% of the introductions in the Indian journals used citations in Move 1, resulting in a significant difference, t(58) = 3.79, p < .001, d = .99. To compare the total frequency of citations, we calculated the relative frequency of citations in relation to the length of the introduction. As hypothesized, we found that the relative frequency of citations in the introductions differed significantly, t(49) = 4.24, p < .001, d = 1.17 (Table 5).

Lastly, the third hypothesis (H3) was tested with an independent two-sample t test, t(58) = 6.84, p < .001, d = 1.77, and again resulted in a confirmation of our hypothesis by showing that the move order (3)-1-2-3 in introductions can be found significantly more often in US than in Indian research articles (for details see Table 6).

Discussion

The aim of this study was to identify key characteristics of introductions in US-based management research articles using an applied linguistics model of introductions and thereby illuminate expectations of editors and reviewers from leading management journals. Furthermore, by comparing the characteristics of introductions in US-based journals with journals from India, we wanted to show how expectations of the research community across the world might differ. Using the CARS model we find that papers published in US-based management journals have a very similar rhetorical structure of introductions, whereas leading Indian management journals strongly differ from the rhetorical structure in the US.

First, we identified the key characteristics of introductions in US-based journals: As indicated by the CARS model (Swales 2004), all three rhetorical moves, i.e., establishing a territory, establishing a niche, and occupying a niche can be found in almost all introductions. Furthermore, within the second move, most of the researchers in US-based management journals seem to employ the strategy of “indicating a research gap”, whereas comparatively fewer researchers choose to go with “adding to what is known”. Interestingly, almost half of the researchers also “provide positive justification” for establishing a niche, which according to Swales (2004) is only an optional rhetorical step. Within the third move a common rhetorical pattern seems to be to “announce present research descriptively and/or purposively”, then to “present research questions or hypotheses”, and to end with “stating the value of the present research”. Additionally, in almost half of the cases “summarizing the methods” was used as well. Lastly, an introduction, on average, seemed to consist of 5330 characters and used a mean of 26.20 references.

Second, we tested whether introductions in US-based journals significantly differed from Indian research article introductions. Our results supported our hypothesis, showing that not only did Indian research articles use significantly less rhetorical moves but also less rhetorical steps, making the Indian research articles very likely to violate expectations of US-based journals’ editors and reviewers. Furthermore, the introductions in Indian research articles were significantly shorter.

Third, we compared the usage of citations in US-based and Indian management journals. Although Swales’ (2004) CARS model postulates that it is required to use citations in the first step of the first move, some Indian journal articles used no citations at all in this particular step. Furthermore, articles in Indian management journals’ articles seem to have significantly fewer citations in the introduction, indicating that it is likely that expectations of US based-journal editors and reviewers are unmet.

Last, we tested the pattern of arguments in US and Indian introductions. Again, confirming our hypothesis, we found that introductions in US-based journals significantly differed from Indian introductions. As defined by the CARS model, US-based journal introductions almost always used the (3)-1-2-3 move order, whereas Indian journal introductions seldom used the expected move order. Furthermore, in some cases Indian articles did not use any kind of introduction, but rather started off with the theoretical background. Thus, it seems plausible to assume that Indian articles’ introductions would likely violate the expectations of editors and reviewers from the US.

Our study demonstrates the power of using an evidence-based approach towards developing academic writing advice. The CARS model from the field of applied linguistics provides a very detailed framework to analyze introductions and illustrates evidence-based implicit expectations that the research community in a particular field might have in respect to the introduction. Our analysis illustrates that editors and reviewers of US-based management journals have a very similar expectation regarding the rhetorical aspects of an introduction, whereas at the same time these expectations differ in other countries, which is likely to affect the visibility of international researchers in leading management journals (Bajwa et al. 2016; Eden and Rynes 2003; George 2012). Particularly, using this evidence-based approach our analysis identifies the key aspects of introductions in leading management journals.

Hence, the implications of our study are threefold. First, management researchers can use the CARS model as a checklist while writing an introduction and based on our analysis they should be able to account for the basic expectations that editors’ and reviewers of leading management journals might have. Second, management educators could use the CARS model to help PhD students understand how to write introductions (Hsu and Liu 2018). Third, the CARS model might help editors and reviewers to get a better insight into their own expectations and provide prospective authors with a more detailed and evidence-based feedback on their introductions. Our hope is that authors who get feedback from editors and reviewers based on the CARS model should be better equipped to understand and implement the feedback, saving both parties valuable time and resources (see Bergh 2002).

As with all studies, this study has its limitations. As we only compared US-based journals with Indian journals, reservations could be raised whether the findings in the Indian journals can be generalized to non-US journals in general. However, our main focus in this study was to identify the characteristics of introductions in US-based journals and Indian journals only functioned as an exemplary comparison. Nonetheless, we acknowledge that an analysis of more countries could provide international researchers from different countries an opportunity to reflect on their own expectations and could be part of future research.

As our study is one of the few to incorporate knowledge from the field of applied linguistics to academic writing in management, there is certainly a lot of further potential for an evidence-based exploration of expectations of editors and reviewers of high impact management journals. Future research could, for example, use applied linguistics models that analyze the flow of arguments (Johns 1986).

Change history

11 August 2021

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-021-04122-7

References

Academy of Management. (2019). Member statistics. http://aom.org/Member-Services/Member-Statistics.aspx. Accessed February 20, 2019.

Ahlstrom, D., Bruton, G. D., & Zhao, L. (2013). Turning good research into good publications. Nankai Business Review International, 4(2), 92–106. https://doi.org/10.1108/20408741311323317.

APA. (2018). Summary report of journal operations, 2017. American Psychologist, 73(5), 683–684. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000347.

Ashford, S. J. (2013). Having scholarly impact: The art of hitting academic home runs. Academy of Management Learning & Education, 12(4), 623–633. https://doi.org/10.5465/amle.2013.0090.

Bajwa, N. H., König, C., & Harrison, O. (2016). Towards evidence-based writing advice: Using applied linguistics to understand reviewers’ expectations. Academy of Management Learning & Education, 15, 419–434. https://doi.org/10.5465/amle.2015.0002.

Barney, J. (2018). Editor’s comments: Positioning a theory paper for publication. Academy of Management Review. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2018.0112.

Bartunek, J. M., Rynes, S. L., & Ireland, R. D. (2006). What makes management research interesting, and why does it matter? Academy of Management Journal, 49(1), 9–15. https://doi.org/10.2307/20159741.

Baruch, Y. (2001). Global or North American? A geographical based comparative analysis of publications in top management journals. International Journal of Cross Cultural Management, 1(1), 109–126. https://doi.org/10.1177/147059580111010.

Belcher, D. D. (2009). How research space is created in a diverse research world. Journal of Second Language Writing, 18(4), 221–234. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jslw.2009.08.001.

Bergh, D. (2002). Deriving greater benefit from the reviewing process. Academy of Management Journal, 45(4), 633–636. https://doi.org/10.5465/AMJ.2002.17460770.

Biber, D. (2007). Discourse on the move: Using corpus analysis to describe discourse structure. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing.

Bono, J. E., & McNamara, G. (2011). Publishing in AMJ—Part 2: Research design. Academy of Management Journal, 54(4), 657–660. https://doi.org/10.5465/AMJ.2011.64869103.

Burgess, T. F., & Shaw, N. E. (2010). Editorial board membership of management and business Journals: A social network analysis study of the Financial Times 40. British Journal of Management, 21(3), 627–648. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8551.2010.00701.x.

Cadman, K. (1997). Thesis writing for international students: A question of identity? English for Specific Purposes, 16(1), 3–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0889-4906(96)00029-4.

Canagarajah, A. S. (2002). Geopolitics of academic writing. Pittsburgh, PA: University of Pittsburgh Press.

Cascio, W. F., & Aguinis, H. (2008). Research in industrial and organizational psychology from 1963 to 2007: Changes, choices, and trends. Journal of Applied Psychology, 93(5), 1062–1081. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.93.5.1062.

Chang, C.-F., & Kuo, C.-H. (2011). A corpus-based approach to online materials development for writing research articles. English for Specific Purposes, 30(3), 222–234. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esp.2011.04.001.

Clark, T., Wright, M., & Ketchen, D. J. (2017). How to get published in the best management journals. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Colquitt, J. A., & George, G. (2011). Publishing in AMJ—Part 1: Topic choice. Academy of Management Journal, 54(3), 432–435. https://doi.org/10.5465/AMJ.2011.61965960.

Davies, A., & Elder, C. (Eds.). (2004). Applied linguistics: Subject to discipline? In The handbook of applied linguistics. Padstow, UK: Wiley.

Day, R. A. (1989). The origins of the scientific paper: The IMRAD format. Journal of the American Medical Writers Association, 4(2), 16–18.

Dueñas, M. P. M. (2012). Getting research published internationally in English: An ethnographic account of a team of Finance Spanish scholars’ struggles. Ibérica: Revista de la Asociación Europea de Lenguas para Fines Específicos, 24, 139–155.

Eden, D., & Rynes, S. (2003). Publishing across borders: Furthering the internationalization of “AMJ”. Academy of Management Journal, 46(6), 679–683. https://doi.org/10.5465/AMJ.2003.11901933.

Fakhri, A. (2004). Rhetorical properties of Arabic research article introductions. Journal of Pragmatics, 36(6), 1119–1138. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2003.11.002.

George, G. (2012). Publishing in AMJ for non-U.S. authors. Academy of Management Journal, 55(5), 1023–1026. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2012.4005.

George, G. (2015). Publishing in AMJ: Tips from the editors (AOM 2015 PDW Vancouver). Presentation presented at the 75th annual meeting of the academy of management, Vancouver, BC. http://aom.org/uploadedFiles/Publications/AMJ/AMJ%20PDW%20GG%202015.pdf. Accessed September 2, 2015.

George, G. (2016). Management research in AMJ: Celebrating impact while striving for more. Academy of Management Journal. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2016.4006.

Golde, C. M., & Dore, T. M. (2001). At cross purposes: What the experiences of today’s doctoral students reveal about doctoral education (Report). http://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED450628. Accessed June 5, 2015.

Grant, A. M., & Pollock, T. G. (2011). Publishing in AMJ—Part 3: Setting the hook. Academy of Management Journal, 54(5), 873–879. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2011.4000.

Harzing, A.-W. (2007). Publish or Perish. https://harzing.com/resources/publish-or-perish. Accessed 12 Mar 2019.

Hayes, A. F., & Krippendorff, K. (2007). Answering the call for a standard reliability measure for coding data. Communication Methods and Measures, 1(1), 77–89. https://doi.org/10.1080/19312450709336664.

Hirano, E. (2009). Research article introductions in English for specific purposes: A comparison between Brazilian Portuguese and English. English for Specific Purposes, 28, 240–250. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esp.2009.02.001.

Hollenbeck, J. R. (2008). The role of editing in knowledge development: Consensus shifting and consensus creation. In Y. Baruch, A. M. Konrad, H. Aguinis, & W. H. Starbuck (Eds.), Opening the black box of editorship (pp. 16–26). Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan.

Holmes, J. (1988). Doubt and certainty in ESL textbooks. Applied Linguistics, 9(1), 21–44. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/9.1.21.

Horn, S. A. (2017). Non-English nativeness as stigma in academic settings. Academy of Management Learning & Education, 16(4), 579–602. https://doi.org/10.5465/amle.2015.0194.

Hsu, W.-C., & Liu, G.-Z. (2018). Genre-based writing instruction blended with an online writing tutorial system for the development of academic writing. Digital Scholarship in the Humanities, Advance online publication.. https://doi.org/10.1093/llc/fqy021.

Huff, A. S. (1999). Writing for scholarly publication. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Hwang, K. (2005). The inferior science and the dominant use of English in knowledge production: A case study of Korean science and technology. Science Communication, 26(4), 390–427. https://doi.org/10.1177/1075547005275428.

Hyland, K. (2002). Genre: Language, context, and literacy. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics, 22, 113–135. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0267190502000065.

Jacobsson, M., & Hällgren, M. (2014). The grabber: Making a first impression the Wilsonian way. International Journal of Managing Projects in Business, 7(4), 739–751. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJMPB-05-2014-0043.

Johns, A. M. (1986). Coherence and academic writing: Some definitions and suggestions for teaching. TESOL Quarterly, 20(2), 247–265. https://doi.org/10.2307/3586543.

Judge, T. A., Cable, D. M., Colbert, A. E., & Rynes, S. L. (2007). What causes a management article to be cited: Article, author, or journal? Academy of Management Journal, 50(3), 491–506. https://doi.org/10.5465/AMJ.2007.25525577.

Kelemen, M., & Bansal, P. (2002). The conventions of management research and their relevance to management practice. British Journal of Management, 13(2), 97–108. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8551.00225.

Krippendorff, K. H. (2012). Content analysis: An introduction to its methodology (3rd ed.). Los Angeles, CA: Sage.

Kwan, B. S. C. (2013). Facilitating novice researchers in project publishing during the doctoral years and beyond: A Hong Kong-based study. Studies in Higher Education, 38, 207–225. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2011.576755.

Lim, J. M.-H. (2012). How do writers establish research niches? A genre-based investigation into management researchers’ rhetorical steps and linguistic mechanisms. Journal of English for Academic Purposes, 11(3), 229–245. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeap.2012.05.002.

Locke, K., & Golden-Biddle, K. (1997). Constructing opportunities for contribution: Structuring intertextual coherence and “problematizing” in organizational studies. The Academy of Management Journal, 40(5), 1023–1062. https://doi.org/10.2307/256926.

Loi, C. K. (2010). Research article introductions in Chinese and English: A comparative genre-based study. Journal of English for Academic Purposes, 9(4), 267–279. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeap.2010.09.004.

Milagros del Saz Rubio, M. (2011). A pragmatic approach to the macro-structure and metadiscoursal features of research article introductions in the field of agricultural sciences. English for Specific Purposes, 30(4), 258–271. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esp.2011.03.002.

Mozaheb, M. A., Saeidi, M., & Ahangari, S. (2014). A comparative genre-based study of research articles’ introductions written by English native/non native speakers. Calidoscópio, 12(3), 323–334. https://doi.org/10.4013/cld.2014.123.07.

Mu, C., & Zhang, L. J. (2018). Understanding Chinese multilingual scholars’ experiences of publishing research in English. Journal of Scholarly Publishing. https://doi.org/10.3138/jsp.49.4.02.

Nicoll, K., & Harrison, R. (2003). Constructing the good teacher in higher education: The discursive work of standards. Studies in Continuing Education, 25(1), 23. https://doi.org/10.1080/01580370309289.

Pho, P. D. (2008). Research article abstracts in applied linguistics and educational technology: A study of linguistic realizations of rhetorical structure and authorial stance. Discourse Studies, 10, 231–250. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461445607087010.

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Podsakoff, N. P., & Bachrach, D. G. (2008). Scholarly influence in the field of management: A bibliometric analysis of the determinants of university and author impact in the management literature in the past quarter century. Journal of Management, 34(4), 641–720. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206308319533.

Pudelko, M., & Tenzer, H. (2018). Boundaryless careers or career boundaries? The impact of language barriers on academic careers in international business schools. Academy of Management Learning & Education. https://doi.org/10.5465/amle.2017.0236.

Rynes, S. L., Hillman, A., Ireland, R. D., Kirkman, B., Law, K., Miller, C. C., et al. (2005). Everything you’ve always wanted to know about AMJ (but may have been afraid to ask). Academy of Management Journal, 48(5), 732–737. https://doi.org/10.5465/AMJ.2005.28563879.

Samraj, B. (2002). Introductions in research articles: Variations across disciplines. English for Specific Purposes, 21(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0889-4906(00)00023-5.

Sandberg, J., & Alvesson, M. (2011). Ways of constructing research questions: Gap-spotting or problematization? Organization, 18(1), 23–44. https://doi.org/10.1177/1350508410372151.

Sheldon, E. (2011). Rhetorical differences in RA introductions written by English L1 and L2 and Castilian Spanish L1 writers. Journal of English for Academic Purposes, 10(4), 238–251. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeap.2011.08.004.

Sparrowe, R. T., & Mayer, K. J. (2011). Publishing in AMJ—Part 4: Grounding hypotheses. Academy of Management Journal, 54(6), 1098–1102. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2011.4001.

Starkey, K., & Madan, P. (2001). Bridging the relevance gap: Aligning stakeholders in the future of management research. British Journal of Management, 12, S3–S26. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8551.12.s1.2.

Swales, J. (1981). Aspects of article introductions. Birmingham: Language Studies Unit, University of Aston.

Swales, J. (1990). Genre analysis: English in academic and research settings. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Swales, J. (2004). Research genres: Explorations and applications. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Swales, J. (2015). Question on introductions in management articles.

Swales, J., & Najjar, H. (1987). The writing of research article introductions. Written Communication, 4(2), 175–191. https://doi.org/10.1177/0741088387004002004.

Verbi GmbH. (2013). MAXQDA. Berlin: VERBI Software – Consult – Sozialforschung GmbH.

Voordeckers, W., Breton-Miller, I. L., & Miller, D. (2014). In search of the best of both worlds: Crafting a finance paper for the Family Business Review. Family Business Review, 27(4), 281–286. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894486514552175.

Webster, J., & Watson, R. T. (2002). Analyzing the past to prepare for the future: Writing a literature review. Management Information Systems Quarterly, 26(2), xiii–xxiii.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

The original online version of this article was revised due to a retrospective Open Access order.

Appendix

Appendix

List of analyzed papers

Agarwal, P. (2011). Relationship between psychological contract & organizational commitment in Indian IT industry. Indian Journal of Industrial Relations, 47(2), 290–305.

Aguinis, H., Dalton, D. R., Bosco, F. A., Pierce, C. A., & Dalton, C. M. (2011). Meta-analytic choices and judgment calls: Implications for theory building and testing, obtained effect sizes, and scholarly impact. Journal of Management, 37(1), 5–38. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206310377113.

Babu, V. (2011). Divergent leadership styles practiced by global managers in India. Indian Journal of Industrial Relations, 46(3), 478–490.

Bae, J., Wezel, F. C., & Koo, J. (2011). Cross-cutting ties, organizational density, and new firm formation in the U.S. biotech industry, 1994–98. Academy of Management Journal, 54(2), 295–311. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2011.60263089.

Bell, S. T., Villado, A. J., Lukasik, M. A., Belau, L., & Briggs, A. L. (2011). Getting specific about demographic diversity variable and team performance relationships: A meta-analysis. Journal of Management, 37(3), 709–743. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206310365001.

Bhattacharya, A. (2011). Predictability of job-satisfaction: An analysis from age perspective. Indian Journal of Industrial Relations, 46(3), 498–509.

Biswas, M. (2011). Moral competency: Deconstructing the decorated self. Vision: The Journal of Business Perspective, 15(2), 115–125. https://doi.org/10.1177/097226291101500204.

Carlson, D. S., Ferguson, M., Kacmar, K. M., Grzywacz, J. G., & Whitten, D. (2011). Pay it forward: The positive crossover effects of supervisor work—family enrichment. Journal of Management, 37(3), 770–789. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206310363613.

Chawla, D., & Sondhi, N. (2011). Assessing work-life balance among Indian women professionals. Indian Journal of Industrial Relations, 47(2), 341–352.

Choudhury, R. R., & Gupta, V. (2011). Impact of age on pay satisfaction and job satisfaction leading to turnover intention: A study of young working professionals in India. Management and Labour Studies, 36(4), 353–363. https://doi.org/10.1177/0258042X1103600404.

Christian, M. S., & Ellis, A. P. J. (2011). Examining the effects of sleep deprivation on workplace deviance: A self-regulatory perspective. Academy of Management Journal, 54(5), 913–934. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2010.0179.

Colman, H. L., & Lunnan, R. (2011). Organizational identification and serendipitous value creation in post-acquisition integration. Journal of Management, 37(3), 839–860. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206309354645.

Cook, A., & Glass, C. (2011). Leadership change and shareholder value: How markets react to the appointments of women. Human Resource Management, 50(4), 501–519. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.20438.

Dodrajka, S. (2011). Surrogate advertising in India. Management and Labour Studies, 36(3), 281–290. https://doi.org/10.1177/0258042X1103600305.

Ellis, K. M., Reus, T. H., Lamont, B. T., & Ranft, A. L. (2011). Transfer effects in large acquisitions: How size-specific experience matters. Academy of Management Journal, 54(6), 1261–1276. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2009.0122.

Gaan, N. (2011). Development of emotional labour scale in Indian context. Vision: The Journal of Business Perspective, 15(1), 41–48. https://doi.org/10.1177/097226291101500105.

Green, S. G., Bull Schaefer, R. A., MacDermid, S. M., & Weiss, H. M. (2011). Partner reactions to work-to-family conflict: Cognitive appraisal and indirect crossover in couples. Journal of Management, 37(3), 744–769. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206309349307.

Herrero, I. (2011). Agency costs, family ties, and firm efficiency. Journal of Management, 37(3), 887–904. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206310394866.

Hirst, G., Van Knippenberg, D., Chen, C.-H., & Sacramento, C. A. (2011). How does bureaucracy impact individual creativity? A cross-level investigation of team contextual influences on goal orientation–creativity relationships. Academy of Management Journal, 54(3), 624–641. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2011.61968124.

Hoffman, B. J., Bynum, B. H., Piccolo, R. F., & Sutton, A. W. (2011). Person-organization value congruence: How transformational leaders influence work group effectiveness. Academy of Management Journal, 54(4), 779–796. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2011.64870139.

Holland, P., Pyman, A., Cooper, B. K., & Teicher, J. (2011). Employee voice and job satisfaction in Australia: The centrality of direct voice. Human Resource Management, 50(1), 95–111. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.20406.

Jyoti, J., Gupta, P., & Kotwal, S. (2011). Impact of knowledge management practices on innovative capacity: A study of telecommunication sector. Vision: The Journal of Business Perspective, 15(4), 315–330. https://doi.org/10.1177/097226291101500402.

Kang, L. S., & Sandhu, R. S. (2011). Job & family related stressors among bank branch managers in India. Indian Journal of Industrial Relations, 47(2), 329–340.

Kaplan, D. M., Wiley, J. W., & Maertz, C. P. (2011). The role of calculative attachment in the relationship between diversity climate and retention. Human Resource Management, 50(2), 271–287. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.20413.

Kodan, A. S., & Chhikara, K. S. (2011). Status of financial inclusion in Haryana: An evidence of commercial banks. Management and Labour Studies, 36(3), 247–267. https://doi.org/10.1177/0258042X1103600303.

Kumar, C. S. (2011). Job stress and job satisfaction of IT companies’ employees. Management and Labour Studies, 36(1), 61–72. https://doi.org/10.1177/0258042X1103600104.

Kumar, M., & Singh, S. (2011). Leader-member exchange & perceived organizational justice—An empirical investigation. Indian Journal of Industrial Relations, 47(2), 277–289.

Li, J., Chu, C. W. L., Lam, K. C. K., & Liao, S. (2011). Age diversity and firm performance in an emerging economy: Implications for cross-cultural human resource management. Human Resource Management, 50(2), 247–270. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.20416.

Lux, S., Crook, T. R., & Woehr, D. J. (2011). Mixing business with politics: A meta-analysis of the antecedents and outcomes of corporate political activity. Journal of Management, 37(1), 223–247. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206310392233.

Malhotra, D., & Lumineau, F. (2011). Trust and collaboration in the aftermath of conflict: The effects of contract structure. Academy of Management Journal, 54(5), 981–998. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2009.0683.

McClean, E., & Collins, C. J. (2011). High-commitment HR practices, employee effort, and firm performance: Investigating the effects of HR practices across employee groups within professional services firms. Human Resource Management, 50(3), 341–363. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.20429.

McDonald, M. L., & Westphal, J. D. (2011). My brother’s keeper? CEO identification with the corporate elite, social support among CEOs, and leader effectiveness. Academy of Management Journal, 54(4), 661–693. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2011.64869104.

Melkonian, T., Monin, P., & Noorderhaven, N. G. (2011). Distributive justice, procedural justice, exemplarity, and employees’ willingness to cooperate in M&A integration processes: An analysis of the Air France-KLM merger. Human Resource Management, 50(6), 809–837. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.20456.

Mishra, P. K. (2011). Dynamics of the relationship between mutual funds investment flow and stock market returns in India. Vision: The Journal of Business Perspective, 15(1), 31–40. https://doi.org/10.1177/097226291101500104.

Mittal, M. (2011). Television viewing and perception of parental concern among urban Indian children. Management and Labour Studies, 36(1), 45–59. https://doi.org/10.1177/0258042X1103600103.

Mogla, M., & Singh, F. (2011). Performance comparison of group vis-à-vis non-group mergers. Vision: The Journal of Business Perspective, 15(1), 11–19. https://doi.org/10.1177/097226291101500102.

Mohapatra, M., & Srivastava, B. (2011). Career in consultancy: Problems and prospects for women in India. Management and Labour Studies, 36(1), 31–44. https://doi.org/10.1177/0258042X1103600102.

Narang, L., & Singh, L. (2011). Human resource practices and perceived organizational support—A relationship in Indian context. Management and Labour Studies, 36(3), 217–224. https://doi.org/10.1177/0258042X1103600301.

Ndofor, H. A., & Priem, R. L. (2011). Immigrant entrepreneurs, the ethnic enclave strategy, and venture performance. Journal of Management, 37(3), 790–818. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206309345020.

O’Neill, O. A., Feldman, D. C., Vandenberg, R. J., DeJoy, D. M., & Wilson, M. G. (2011). Organizational achievement values, high-involvement work practices, and business unit performance. Human Resource Management, 50(4), 541–558. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.20437.

Pandey, A., & Kumar, S. B. (2011). Volatility transmission from global stock exchanges to India: An empirical assessment. Vision: The Journal of Business Perspective, 15(4), 347–360. https://doi.org/10.1177/097226291101500404.

Reinholt, M., Pedersen, T., & Foss, N. J. (2011). Why a central network position isn’t enough: The role of motivation and ability for knowledge sharing in employee networks. Academy of Management Journal, 54(6), 1277–1297. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2009.0007.

Riasudeen, S., & Srinivasan, P. T. (2011). Group factors and its relationship with job and life satisfaction in diverse organizations. Management and Labour Studies, 36(4), 335–352. https://doi.org/10.1177/0258042X1103600403.

Rosen, C. C., Harris, K. J., & Kacmar, K. M. (2011). LMX, context perceptions, and performance: An uncertainty management perspective. Journal of Management, 37(3), 819–838. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206310365727.

Sahay, Y. P., & Gupta, M. (2011). Role of organization structure in innovation in the bulk-drug industry. Indian Journal of Industrial Relations, 46(3), 450–464.

Shahnawaz, M. G., & Goswami, K. (2011). Effect of psychological contract violation on organizational commitment, trust and turnover intention in private and public sector Indian organizations. Vision: The Journal of Business Perspective, 15(3), 209–217. https://doi.org/10.1177/097226291101500301.

Shantz, A., & Latham, G. (2011). The effect of primed goals on employee performance: Implications for human resource management. Human Resource Management, 50(2), 289–299. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.20418.

Shin, J. Y., & Seo, J. (2011). Less pay and more sensitivity? Institutional investor heterogeneity and CEO pay. Journal of Management, 37(6), 1719–1746. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206310372412.

Singh, A. K. (2011). HRD practices & managerial effectiveness: Role of organisation culture. Indian Journal of Industrial Relations, 47(1), 138–148.

Srivastava, M. (2011). Anxiety, stress and satisfaction among professionals in manufacturing and service organizations: Fallout of personal values, work values and extreme job conditions. Vision: The Journal of Business Perspective, 15(3), 219–229. https://doi.org/10.1177/097226291101500302.

Srivastava, M., & Sinha, A. K. (2011). Task characteristics & group effectiveness in Indian organizations. Indian Journal of Industrial Relations, 46(4), 699–712.

Srivastava, N., & Nair, S. K. (2011). Androgyny and rational emotive behaviour as antecedents of managerial effectiveness. Vision: The Journal of Business Perspective, 15(4), 303–314. https://doi.org/10.1177/097226291101500401.

Srivastava, Shalini. (2011). Assessing the relationship between personality variable and managerial effectiveness: An empirical study on private sector managers. Management and Labour Studies, 36(4), 319–333. https://doi.org/10.1177/0258042X1103600402.

Srivastava, Shalini, & Pathak, D. (2011). Moderating effect of personality variable on stress-effectiveness relationship: An empirical study on B-school students. Vision: The Journal of Business Perspective, 15(1), 21–30. https://doi.org/10.1177/097226291101500103.

Srivastava, Sushmita. (2011a). Commitment & loyalty to trade unions: Revisiting Gordon’s & Hirschman’s theories. Indian Journal of Industrial Relations, 47(2), 206–218.

Srivastava, Sushmita. (2011b). A study of the impact of types of job change on perceived performance of newly rotated managers: The mediating role of job change dimensions. Management and Labour Studies, 36(1), 73–98. https://doi.org/10.1177/0258042X1103600105.

Teerikangas, S., Véry, P., & Pisano, V. (2011). Integration managers’ value-capturing roles and acquisition performance. Human Resource Management, 50(5), 651–683. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.20453.

Walsh, I. J., & Bartunek, J. M. (2011). Cheating the fates: Organizational foundings in the wake of demise. Academy of Management Journal, 54(5), 1017–1044. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2008.0658.

Yan, M., Peng, K. Z., & Francesco, A. M. (2011). The differential effects of job design on knowledge workers and manual workers: A quasi-experimental field study in China. Human Resource Management, 50(3), 407–424. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.20428.

Yang, H., Lin, Z. (John), & Peng, M. W. (2011). Behind acquisitions of alliance partners: Exploratory learning and network embeddedness. Academy of Management Journal, 54(5), 1069–1080. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2007.0767.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bajwa, N.H., König, C.J. & Kunze, T. Evidence-based understanding of introductions of research articles. Scientometrics 124, 195–217 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-020-03475-9

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-020-03475-9