Abstract

Warthin tumour is the second most common benign neoplasm of salivary glands. Despite its relatively characteristic histology, it may sometimes mimic other lesions. Here, we report two female non-smoker patients diagnosed with low-grade mucoepidermoid carcinoma with oncocytic epithelium and prominent lymphoid (Warthin-like) stroma and with molecularly confirmed MAML2 rearrangement. In addition, we screened a consecutive series of 114 Warthin tumour cases by means of MAML2 break apart fluorescence in situ hybridization to assess its value in differential diagnosis. MAML2 rearrangement was detected in both mucoepidermoid carcinoma cases, while all Warthin tumours were negative. Taking into account the literature data, Warthin-like mucoepidermoid carcinomas are more frequently observed in women, while a slight male predominance and smoking history are typical for Warthin tumour. In addition, the patients with Warthin-like mucoepidermoid carcinoma were significantly younger than those with Warthin tumour. To conclude, Warthin-like mucoepidermoid carcinoma may usually be suspected based on histology, while the diagnosis can be confirmed by means of molecular assays such as FISH. The investigation of MAML2 status is particularly advised when Warthin tumour is considered in a young, non-smoking, female patient.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Warthin tumour (WT) is the second most common benign neoplasm of salivary glands. It usually arises as a slow-growing, painless mass in the parotid of male smokers [1]. The mechanism of WT development has not been clearly defined; however, smoking-induced oncocytic metaplasia and salivary gland heterotopia in peri- and intraparotideal lymph nodes are most probably involved [2]. Conventional WT is characterized by a dense lymphoid stroma and cystic spaces lined by bilayer oncocytic epithelium forming papillary projections. Its metaplastic or infarcted variants display coagulative necrosis, fibrosis, and inflammation along with squamous or mucinous metaplasia, but with no cytological atypia or invasive growth pattern [3]; an association with prior biopsy of the tumour has been postulated [4]. In contrast, WT-like mucoepidermoid carcinoma exhibits atypical bilayer oncocytic epithelium with no “typical” bilayer epithelium of WT along with the presence of dense lymphoid stroma and squamoid or goblet-like cells. On the other hand, oncocytic MEC shows the proliferation of oncocytic cells embedded in a desmoplastic stroma infiltrated by a variable number of lymphocytes [5]. Finally, otherwise conventional mucoepidermoid carcinomas frequently show prominent lymphoid proliferation along the infiltrative tumour edge and are sometimes referred to as MUC with tumour-associated lymphoid proliferation [6]. Nonetheless, the microscopic features of the above-mentioned entities overlap to some extent, thus complicating the differential diagnosis, which should include oncocytic papillary cystadenoma, lymphoepithelial lesions (e.g. simple benign lymphoepithelial cyst) and cystic lymph nodes metastases (e.g. so-called Warthin-like papillary thyroid carcinoma) [7] as well as low-grade squamous or mucoepidermoid carcinoma (MEC) [4].

Originally, García et al. reported a series of 12 oncocytic MECs in 2011 [8]. Among these, 5 were described as having Warthin-like histology (all such cases reported to date are summarized in Table 1 [8,9,10,11,12,13,14]) and harboured a mastermind-like transcriptional coactivator 2 (MAML2) rearrangement. This alteration occurs in > 50% of MECs and correlates with low-/intermediate-grade histology and a better prognosis [15]. Its most common underlying mechanism is t(11;19) translocation, producing CREB-regulated transcription coactivator 1 (CRTC1)-MAML2 gene fusion. Subsequently, Ishibashi et al. coined a new term: Warthin-like MEC (WL-MEC) for a subset of tumours characterized by prominent lymphoid stroma and MAML2 rearrangement [9]. The distinction between true WT and Warthin-like MEC is crucial as it carries vital clinical consequences. Histopathological features are usually sufficient to obtain the definitive diagnosis; however, recently, Akaev et al. reported a case of MEC with tumour-associated lymphoid proliferation indistinguishable from benign WT by histology and immunohistochemistry [13]. To date, all reported cases of Warthin-like MEC have been associated with MAML2 rearrangements; thus, the molecular test may provide the definitive answer [12]. On the other hand, it is still unclear whether “classic” WT may exceptionally harbour such translocations.

Here, we describe two new cases of low-grade MEC with prominent lymphoid (Warthin-like) stroma and with molecularly confirmed MAML2 rearrangement. In addition, we screened a consecutive series of 114 WT cases by means of MAML2 break apart fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH).

Case reports

Case I

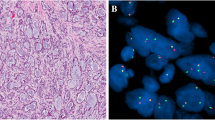

A 30-old female non-smoking patient was admitted due to a tumour of the right parotid gland. The lesion was first noted 6 months earlier and caused no discomfort. Of note, 11 years earlier, the patient was diagnosed with Hodgkin’s lymphoma and successfully treated with chemotherapy (no radiotherapy on the neck has been applied). On palpation, the lesion was about 1 cm large, non-movable and not tender; the overlying skin was normal. Grossly, the resected lesion was grey-tan and poorly demarcated from the normal gland. The histological image presented a nonencapsulated tumour with lymphoepithelial growth pattern. It formed numerous cystic structures with variable size and shape, filled with proteinaceous material (Fig. 1a) and surrounded by dense lymphocytic infiltrate with lymphoid follicle formation (Fig. 1b). The epithelium is multilayered and partially oncocytic, containing single scattered mucus-producing cells, confirmed with mucicarmine stain (Fig. 1c, d). No signs of perineurial invasion, necrosis or anaplasia were noted. Thus, mucoepidermoid carcinoma was diagnosed and subsequently assigned as low-grade according to all common grading systems (Modified Healey, AFIP, Brandwein, and Katabi) [16]. MAML2 rearrangement was confirmed with FISH (Fig. 1f). Due to the resection margins tangent to the tumour tissue, viscerocranial magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and ultrasound of salivary glands with FNA biopsy were performed, but showed no signs of the residual tumour.

Case II

A 51-year-old female patient was admitted due to a tumour of the right parotid gland. The lesion was first noted by the patient 7 years earlier and caused no discomfort except for an intermittent otalgia. Fine needle aspiration biopsy was non-diagnostic, while MRI did not allow for differentiation between salivary gland cancers and Warthin tumour (Fig. S1). On palpation, the lesion was about 2 cm large, movable and not tender; the overlaying skin was normal. On gross examination, the lesion was grey-tan and poorly demarcated from the normal gland. The overall histological appearance was similar to the other case. The tumour was nonencapsulated and showed organoid architecture with cystic structures filled with proteinaceous material (Fig. 2a). The accompanying prominent lymphocytic infiltrate forms numerous lymphoid follicles (Fig. 2b). The cysts are lined by eosinophilic squamoid epithelium, and some are subtotally filled with cells showing squamous differentiation mixed with scattered mucus-producing cells (Fig. 2c, d). Thus, MEC was diagnosed, and as in the first case, it was scored low-grade according to the 4 grading systems [16]. MAML2 rearrangement was confirmed with FISH (Fig. 2f). Due to the incomplete resection, reoperation was performed, and the extended resection margins were free from tumour tissue.

Materials and methods

Study group

In addition to the two reported cases of low-grade Warthin-like mucoepidermoid carcinoma, the study group consisted of a consecutive series of 114 Warthin tumour cases diagnosed at the Department of Pathomorphology, Medical University of Gdańsk between 2014 and 2017. Among these, there were 60 males (44 smokers and 4 non-smokers; 91.7%; no data for 12 patients) and 54 females (42 smokers and 6 non-smokers; 87.5%; no data for 6 patients). The median tumour size was 27 mm (range, 6–83 mm). The study was approved by the Bioethical Committee of Medical University of Gdańsk (approval No. NKBBN/207/2019).

Tissue microarrays

Tissue microarrays (TMA) from WT samples consisting of 2 representative core sections (1 mm in diameter) were prepared using the Manual Tissue Arrayer MTA-1 (Beecher Instruments, Inc., USA). Non-neoplastic tissues served as a negative control and location markers.

Fluorescent in situ hybridisation

For the purpose of FISH, 4-μm-thick sections were cut from a representative blocks of both MEC cases and from TMAs. Fluorescent in situ hybridisation was performed in parallel to routine diagnostics using ZytoLight SPEC MAML2 Dual Color Break Apart Probe and ZytoLight FISH-Tissue Implementation Kit (ZytoVision, Bremerhaven, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The slides were evaluated using a fluorescent microscope; all epithelial cells within each core were investigated for the presence of the break apart signal.

Literature search

The search for articles within the PubMed database was performed using the “Warthin-like mucoepidermoid carcinoma” and “Warthin-like MEC” queries (performed on 6 February 2019); subsequently, the reference lists of the included studies were also searched for further articles. Only newly reported cases of MEC with Warthin-like morphology were included in the analysis; thus, 7 studies reporting 20 cases were included (Table 1 [8,9,10,11,12,13,14]). Similarly, the PubMed database was searched using “Warthin MAML2” and “Warthin t(11;19)” queries (performed on 6 February 2019); subsequently, the reference lists of the included studies were also searched for further articles. Thus, 16 studies reporting the MAML2 gene status in a total of 162 cases were identified (Table 2 [17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31]).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using R version 3.5.1. with ggplot2 and gridExtra packages for visualisation [32,33,34]. Continuous variables (age and tumour size) were compared between two groups using Mann-Whitney-Wilcoxon test. Comparison of gender distribution between tumours was performed using chi-squared test.

Results

MAML2 rearrangement was detected in both MEC cases (Figs. 1d, 3d). In contrast, all WT cases were negative for the alteration (0/114).

Warthin-like MEC were more frequently observed in women (18/22 reported cases), while a slight male predominance is indicated for WT (p = 0.003 when compared to our group of WT; p < 0.001 when compared to group reported by Eveson et al. [1, 35]). Additionally, the patients with Warthin-like MEC were significantly younger than those with WT (p < 0.001; Fig. 3a). In contrast, there was no difference in the observed tumour sizes depending on the diagnosis (p > 0.05, Fig. 3b).

Discussion

From the clinical perspective, there is a crucial difference between WT and MEC. While the former is entirely benign, the latter may potentially be lethal. Current guidelines indicate the resection for all parotid gland tumours; for Warthin tumours, partial or superficial resection is preferred whenever possible; however, wait-and-scan strategy is sometimes postulated [36, 37]. On the other hand, total parotidectomy, often accompanied by some degree of neck dissection, is the treatment of choice for MEC; in cases with positive margins or high-grade histology, adjuvant radiotherapy should also be considered [36, 38]. In this context, the recently recognized Warthin-like MEC may be particularly problematic. Its cytological appearance suggests Warthin tumour [10], while the radiological features have not been defined; therefore, in most cases, it has been resected as a benign lesion. Albeit on the less aggressive side of the MEC spectrum, Warthin-like MECs still require a closer follow-up, and clear resection margins are more vital, which emphasize its need to be distinguished from WT. Intriguingly, tumours operated on as benign lesions and postoperatively, unexpectedly, diagnosed as malignant are reported to typically follow a benign course [39,40,41].Warthin-like MEC is a rare and only recently defined entity [9], with few cases described in the literature. Its characteristic morphology along with the MAML2 rearrangement is crucial for the diagnosis. Before it became a commonly recognized diagnosis, parotid tumours with features of both MEC and WT might have been regarded as MEC ex WT or as a collision tumour [42]. The differential diagnosis of Warthin-like MEC includes metaplastic WT, MEC ex WT, and squamous cell carcinoma with prominent lymphoid response. Metaplastic WT is characterized by nonkeratinizing squamoid cells arranged in cords in necrotic areas, usually accompanied by areas of classic WT [43]. Metaplastic cells may be atypical and grow in pseudoinfiltrative pattern suggestive for malignancy. Perplexingly, mucoid metaplasia may occur as well, which may easily lead to misdiagnosis of MEC [3]. However, metaplastic changes in WT are usually focal and admixed with necrosis, haemorrhages and fibrosis associated with prior biopsy [11]. On the other hand, Heatley et al. described a case of Warthin-like MEC recurring after 4 years as obvious MEC [11]. Detailed evaluation of primary slides revealed a 1-mm distinctive area composed of small cysts lined by attenuated epithelial cells and mucous cells. This case emphasizes the importance of careful examination of doubtful WT cases, which should be confirmed by MAML2 gene rearrangement detection by FISH. In our cases, the microscopic appearance of the tumours was masquerading WT by formation of lymphoid stroma, papillary architecture and slightly oncocytic cells; however, other features were strongly suggestive for MEC. FISH for MAML2 confirmed the diagnoses.

Since its discovery [44], the MAML2 rearrangement, typically resulting from t(11;19) translocation, has been generally considered characteristic for low-grade MEC. This concept was recently challenged by Cipriani et al. [16], who critically revised the histological, molecular and clinical features of a series of MECs. They reported that Brandwein grades were the best predictor of recurrence among the available grading systems. In addition, they suggested that high-grade tumours without the MAML2 rearrangement are probably high-grade non-mucoepidermoid carcinomas. Both cases presented here were classified as low-grade according to all 4 grading systems (Modified Healey, AFIP, Brandwein, Katabi) [16]. What is crucial, both formation of large cysts and predominance of the cystic component (which are typical for WT-MECs) are the features of low-grade tumours in all systems. On the other hand, none of them may be suitable for MEC variants, since no differences in outcomes were noted between low-, intermediate- and high-grade oncocytic MECs [5].

The comparison of our group of WTs with all reported Warthin-like MEC cases indicates that the latter are observed in significantly younger patients. What is more, our WT cohort comprised no patients younger than 38 years, while all below 45 years were heavy smokers. Similar observations were reported before [9]. Therefore, the status of MAML2 rearrangement should be investigated when a WT is considered in a young, non-smoking, female patient. Apart from the 2 cases presented here, there is only one WL-MEC case report with a known smoking status, and all 3 patients were non-smokers [14]. Of note, smoking is not considered a strong risk factor for classic MECs [45]. On the other hand, tumour sizes were not significantly different between both investigated tumour types. Still, the group of Warthin-like MECs was relatively small, and these results should be interpreted with caution.

What is noteworthy, some groups reported MAML2 fusions in classic WT, which challenges the value of MAML2 as a diagnostic biomarker of Warthin-like MEC [26]. Early cytogenetic studies demonstrated the occurrence of t(11;19) in two random cases of WT [17, 18]. Subsequently, Nodkvist et al. postulated that t(11;19) defines one of three cytogenetic subgroups in WT [20], while Tirado et al. detected the translocation by RT-PCR in 4/11 WT cases [26]. On the other hand, most of the recent studies did not report translocations involving MAML2 in Warthin tumours (Table 2). Consistently, in the current study, we did not observed any MAML2 rearrangements in the 114 WT cases. This cohort included 4 cases of metaplastic WT, which had histopathological hallmarks of classic WT along with regions of squamous metaplasia. These findings are in line with the study by Ishibashi and colleagues, who showed that MAML2 rearrangement-positive metaplastic WT completely lack the typical oncocytic bilayered epithelium and should be reclassified as low-grade MECs [9]. Nevertheless, another study detected split signals indicative for MAML2 rearrangement in squamous epithelium in two cases of WT with squamous metaplasia, without any accompanying abnormalities in the oncocytic epithelium, lymphocytes and mucinous metaplasia [29]. Recently, Yorita et al. described a case of Warthin tumour with a MEC-like component, in which the lack of MAML2 rearrangement led to the diagnosis of infarcted WT with metaplastic changes [3]. In contrast, mucoepidermoid carcinoma may potentially develop from WT as postulated by Bell et al. [46]. They reported MAML2 rearrangements in a subset of WT coexisting with MEC and suggested the possible histogenetic link between these two entities [46]. According to their model, CRTC1-MAML2 fusion in WT leads to the formation of a more aggressive population, which may transform into MEC. Nevertheless, the cases of MEC ex WT can be relatively easily recognized due to occurrence of transitional areas of squamous metaplasia between the regions of classic WT and obvious MEC [46]. Due to the sparsity of data, it is unknown whether distinguishing between Warthin-like MEC and MEC ex WT has any clinical significance.

It has to be emphasized that this study is the largest reported screening of Warthin tumours by means of break apart FISH to detect the MAML2 rearrangement. The application of TMAs for FISH might be regarded as a limitation; however, others have previously demonstrated the reliability of such an approach as confirmed by real-time polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) [28]. Moreover, the classical bilayer architecture of WTs could readily be appreciated by fluorescent microscopy, while all cores from Warthin-like MEC presented the translocation.

To conclude, Warthin-like MEC may usually be suspected based on histology, while the diagnosis can be confirmed by means of molecular assays such as FISH. In contrast, classic and metaplastic WTs containing the characteristic bilayered oncocytic epithelium are typically not associated with MAML2 rearrangement and usually affect older patients.

References

El-Naggar A, Chan J, Grandis J, et al. (2017) WHO classification of head and neck Tumours. International Agency for Research on Cancer

Cope W, Naugler C, Taylor SM, Trites J, Hart RD, Bullock MJ (2014) The association of warthin tumor with salivary ductal inclusions in intra and periparotid lymph nodes. Head Neck Pathol 8:73–76. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12105-013-0477-5

Yorita K, Nakagawa H, Miyazaki K, Fukuda J, Ito S, Kosai M (2019) Infarcted Warthin tumor with mucoepidermoid carcinoma-like metaplasia: a case report and review of the literature. J Med Case Rep 13:12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13256-018-1941-3

Di Palma S, Simpson RH, Skálová A, Michal M (1999) Metaplastic (infarcted) Warthin’s tumour of the parotid gland: a possible consequence of fine needle aspiration biopsy. Histopathology 35:432–438

Weinreb I, Seethala RR, Perez-Ordoñez B, Chetty R, Hoschar AP, Hunt JL (2009) Oncocytic mucoepidermoid carcinoma: clinicopathologic description in a series of 12 cases. Am J Surg Pathol 33:409–416. https://doi.org/10.1097/PAS.0b013e318184b36d

Auclair PL (1994) Tumor-associated lymphoid proliferation in the parotid gland. A potential diagnostic pitfall. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 77:19–26

Gnepp DR (2009) Diagnostic surgical pathology of the head and neck. Elsevier

García JJ, Hunt JL, Weinreb I, McHugh J, Barnes EL, Cieply K, Dacic S, Seethala RR (2011) Fluorescence in situ hybridization for detection of MAML2 rearrangements in oncocytic mucoepidermoid carcinomas: utility as a diagnostic test. Hum Pathol 42:2001–2009. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.humpath.2011.02.028

Ishibashi K, Ito Y, Masaki A, Fujii K, Beppu S, Sakakibara T, Takino H, Takase H, Ijichi K, Shimozato K, Inagaki H (2015) Warthin-like mucoepidermoid carcinoma: a combined study of fluorescence in situ hybridization and whole-slide imaging. Am J Surg Pathol 39:1479–1487. https://doi.org/10.1097/PAS.0000000000000507

Hang J-F, Shum CH, Ali SZ, Bishop JA (2017) Cytological features of the Warthin-like variant of salivary mucoepidermoid carcinoma. Diagn Cytopathol 45:1132–1136. https://doi.org/10.1002/dc.23785

Heatley N, Harrington KJ, Thway K (2018) Warthin tumor-like mucoepidermoid carcinoma. Int J Surg Pathol 26:31–33. https://doi.org/10.1177/1066896917724889

Bishop JA, Cowan ML, Shum CH, Westra WH (2018) MAML2 rearrangements in variant forms of mucoepidermoid carcinoma: ancillary diagnostic testing for the ciliated and Warthin-like variants. Am J Surg Pathol 42:130–136. https://doi.org/10.1097/PAS.0000000000000932

Akaev I, Yeoh CC, Brennan PA, Rahimi S (2018) Low grade parotid mucoepidermoid carcinoma with tumour associated lymphoid proliferation (“Warthin-like”) and CRTC1-MAML2 fusion transcript: definitive diagnosis with molecular investigation only. Oral Oncol 80:98–99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oraloncology.2018.03.010

Zhang D, Liao X, Tang Y et al (2019) Warthin-like mucoepidermoid carcinoma of the parotid gland: unusual morphology and diagnostic pitfalls. Anticancer Res 39:3213–3217. https://doi.org/10.21873/anticanres.13461

Jee KJ, Persson M, Heikinheimo K, Passador-Santos F, Aro K, Knuutila S, Odell EW, Mäkitie A, Sundelin K, Stenman G, Leivo I (2013) Genomic profiles and CRTC1-MAML2 fusion distinguish different subtypes of mucoepidermoid carcinoma. Mod Pathol 26:213–222. https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.2012.154

Cipriani NA, Lusardi JJ, McElherne J, Pearson AT, Olivas AD, Fitzpatrick C, Lingen MW, Blair EA (2019) Mucoepidermoid carcinoma: a comparison of histologic grading systems and relationship to MAML2 rearrangement and prognosis. Am J Surg Pathol 43:885–897. https://doi.org/10.1097/PAS.0000000000001252

Bullerdiek J, Haubrich J, Meyer K, Bartnitzke S (1988) Translocation t(11;19)(q21;p13.1) as the sole chromosome abnormality in a cystadenolymphoma (Warthin’s tumor) of the parotid gland. Cancer Genet Cytogenet 35:129–132

Mark J, Dahlenfors R, Stenman G, Nordquist A (1989) A human adenolymphoma showing the chromosomal aberrations del (7)(p12p14-15) and t(11;19)(q21;p12-13). Anticancer Res 9:1565–1566

Mark J, Dahlenfors R, Stenman G, Nordquist A (1990) Chromosomal patterns in Warthin’s tumor: a second type of human benign salivary gland neoplasm. Cancer Genet Cytogenet 46:35–39

Nordkvist A, Mark J, Dahlenfors R, Bende M, Stenman G (1994) Cytogenetic observations in 13 cystadenolymphomas (Warthin’s tumors). Cancer Genet Cytogenet 76:129–135

Martins C, Fonseca I, Roque L, Soares J (1997) Cytogenetic characterisation of Warthin’s tumour. Oral Oncol 33:344–347

Martins C, Cavaco B, Tonon G, Kaye FJ, Soares J, Fonseca I (2004) A study of MECT1-MAML2 in mucoepidermoid carcinoma and Warthin’s tumor of salivary glands. J Mol Diagn 6:205–210

Enlund F, Behboudi A, Andrén Y, Oberg C, Lendahl U, Mark J, Stenman G (2004) Altered notch signaling resulting from expression of a WAMTP1-MAML2 gene fusion in mucoepidermoid carcinomas and benign Warthin’s tumors. Exp Cell Res 292:21–28

Winnes M, Enlund F, Mark J, Stenman G (2006) The MECT1-MAML2 gene fusion and benign Warthin’s tumor: is the MECT1-MAML2 gene fusion specific to mucuepidermoid carcinoma? J Mol Diagn 8:394–395 author reply 395–6

Okabe M, Miyabe S, Nagatsuka H, Terada A, Hanai N, Yokoi M, Shimozato K, Eimoto T, Nakamura S, Nagai N, Hasegawa Y, Inagaki H (2006) MECT1-MAML2 fusion transcript defines a favorable subset of mucoepidermoid carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res 12:3902–3907

Tirado Y, Williams MD, Hanna EY, Kaye FJ, Batsakis JG, el-Naggar AK (2007) CRTC1/MAML2 fusion transcript in high grade mucoepidermoid carcinomas of salivary and thyroid glands and Warthin’s tumors: implications for histogenesis and biologic behavior. Genes Chromosom Cancer 46:708–715

Fehr A, Röser K, Belge G et al (2008) A closer look at Warthin tumors and the t(11;19). Cancer Genet Cytogenet 180:135–139. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cancergencyto.2007.10.007

Seethala RR, Dacic S, Cieply K, Kelly LM, Nikiforova MN (2010) A reappraisal of the MECT1/MAML2 translocation in salivary mucoepidermoid carcinomas. Am J Surg Pathol 34:1106–1121. https://doi.org/10.1097/PAS.0b013e3181de3021

Rotellini M, Paglierani M, Pepi M, Franchi A (2012) MAML2 rearrangement in Warthin’s tumour: a fluorescent in situ hybridisation study of metaplastic variants. J Oral Pathol Med 41:615–620. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0714.2012.01159.x

Clauditz TS, Gontarewicz A, Wang C-J et al (2012) 11q21 rearrangement is a frequent and highly specific genetic alteration in mucoepidermoid carcinoma. Diagn Mol Pathol 21:134–137. https://doi.org/10.1097/PDM.0b013e318255552c

Skálová A, Vanecek T, Simpson RHW, Vazmitsel MA, Majewska H, Mukensnabl P, Hauer L, Andrle P, Hosticka L, Grossmann P, Michal M (2013) CRTC1-MAML2 and CRTC3-MAML2 fusions were not detected in metaplastic Warthin tumor and metaplastic pleomorphic adenoma of salivary glands. Am J Surg Pathol 37:1743–1750. https://doi.org/10.1097/PAS.0000000000000065

RC T (2015) R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, 2015). URL: http://www.R-project.org

Wickham H (2009) ggplot2: elegant graphics for data analysis. Springer Science \& Business Media

Auguie B (2017) gridExtra: miscellaneous functions for “grid” graphics

Eveson JW, Cawson RA (1986) Warthin’s tumor (cystadenolymphoma) of salivary glands. A clinicopathologic investigation of 278 cases. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 61:256–262

Thielker J, Grosheva M, Ihrler S, Wittig A, Guntinas-Lichius O (2018) Contemporary Management of Benign and Malignant Parotid Tumors. Front Surg 5:39. https://doi.org/10.3389/fsurg.2018.00039

Espinoza S, Felter A, Malinvaud D, Badoual C, Chatellier G, Siauve N, Halimi P (2016) Warthin’s tumor of parotid gland: surgery or follow-up? Diagnostic value of a decisional algorithm with functional MRI. Diagn Interv Imaging 97:37–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.diii.2014.11.024

Sood S, McGurk M, Vaz F (2016) Management of Salivary Gland Tumours: United Kingdom National Multidisciplinary Guidelines. J Laryngol Otol 130:S142–S149

McGurk M, Thomas BL, Renehan AG (2003) Extracapsular dissection for clinically benign parotid lumps: reduced morbidity without oncological compromise. Br J Cancer 89:1610–1613

Mantsopoulos K, Velegrakis S, Iro H (2015) Unexpected detection of parotid gland malignancy during primary Extracapsular dissection. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 152:1042–1047. https://doi.org/10.1177/0194599815578104

Mantsopoulos K, Koch M, Iro H (2017) Extracapsular dissection as sole therapy for small low-grade malignant tumors of the parotid gland. Laryngoscope 127:1804–1807. https://doi.org/10.1002/lary.26482

Kaur J, Mannan R, Duggal P et al (2012) Fine needle aspiration diagnosis of ipsilateral synchronous neoplasm - mucoepidermoid carcinoma with Warthin tumor in parotid gland. Gulf J Oncol 75–78

Yerli H, Avci S, Aydin E, Arikan U (2010) The metaplastic variant of Warthin tumor of the parotid gland: dynamic multislice computerized tomography and magnetic resonance imaging findings with histopathologic correlation in a case. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 109:e95–e98. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tripleo.2009.10.033

Tonon G, Modi S, Wu L, Kubo A, Coxon AB, Komiya T, O'Neil K, Stover K, el-Naggar A, Griffin JD, Kirsch IR, Kaye FJ (2003) T(11;19)(q21;p13) translocation in mucoepidermoid carcinoma creates a novel fusion product that disrupts a notch signaling pathway. Nat Genet 33:208–213

Sawabe M, Ito H, Takahara T, Oze I, Kawakita D, Yatabe Y, Hasegawa Y, Murakami S, Matsuo K (2018) Heterogeneous impact of smoking on major salivary gland cancer according to histopathological subtype: a case-control study. Cancer 124:118–124. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.30957

Bell D, Luna MA, Weber RS, Kaye FJ, el-Naggar AK (2008) CRTC1/MAML2 fusion transcript in Warthin’s tumor and mucoepidermoid carcinoma: evidence for a common genetic association. Genes Chromosom Cancer 47:309–314. https://doi.org/10.1002/gcc.20534

Funding

This study was supported by the institutional grant of Medical University of Gdańsk, Poland (02-0095/07/267).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Study design: MB, WB

Study overview: WB

Histological review: MB, MK, WB

Radiological review: MS

Cytogenetic analysis: MB, MI, AK

Statistical analysis: MB

Figure preparation: MB

Wrote the manuscript: MB, MK

Critically reviewed the manuscript: MI, AK, MS, WB

Revised the manuscript: MB, MK, WB

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interests.

Ethical approval

The study was approved by the Bioethical Committee of Medical University of Gdańsk (approval No. NKBBN/207/2019).

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

ESM 1

(PNG 2738 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bieńkowski, M., Kunc, M., Iliszko, M. et al. MAML2 rearrangement as a useful diagnostic marker discriminating between Warthin tumour and Warthin-like mucoepidermoid carcinoma. Virchows Arch 477, 393–400 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00428-020-02798-5

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00428-020-02798-5