Abstract

Paraffinic n-alkanes (C22–C30), crucial portions of residual oil, are generally considered to be difficult to be biodegraded owing to their general solidity at ambient temperatures and low water solubility, rendering relatively little known about metabolic processes in different methanogenic hydrocarbon-contaminated environments. Here, we established a methanogenic C22–C30 n-alkane-degrading enrichment culture derived from a high-temperature oil reservoir production water. During two-year incubation (736 days), unexpectedly significant methane production was observed. The measured maximum methane yield rate (164.40 μmol L−1 d−1) occurred during the incubation period from day 351 to 513. The nearly complete consumption (> 97%) of paraffinic n-alkanes and the detection of dicarboxylic acids in n-alkane-amended cultures indicated the biotransformation of paraffin to methane under anoxic condition. 16S rRNA gene analysis suggested that the dominant methanogen in n-alkane-degrading cultures shifted from Methanothermobacter on day 322 to Thermoplasmatales on day 736. Bacterial community analysis based on high-throughput sequencing revealed that members of Proteobacteria and Firmicutes exhibiting predominant in control cultures, while microorganisms affiliated with Actinobacteria turned into the most dominant phylum in n-alkane-dependent cultures. Additionally, the relative abundance of mcrA gene based on genomic DNA significantly increased over the incubation time, suggesting an important role of methanogens in these consortia. This work extends our understanding of methanogenic paraffinic n-alkanes conversion and has biotechnological implications for microbial enhanced recovery of residual hydrocarbons and effective bioremediation of hydrocarbon-containing biospheres.

Similar content being viewed by others

Key points

-

Biotransformation of paraffinic n-alkanes taking place under methanogenic conditions inoculated with high-temperature reservoir water.

-

C22-C30 n-alkanes biodegradation coupling to methane generation.

-

Almost all added substrates were consumed.

-

Actinobacteria becoming predominant in alkane-degrading cultures.

Introduction

Linear alkanes, major and critical constituents of natural gas and crude oil, can be metabolized by microbial consortia in extremely anoxic conditions, as extensively demonstrated in various environments (Boll et al. 2018; Gieg 2018; Rabus et al. 2016). Consequently, in the presence of microbial communities, n-alkanes of different chain lengths, considered as environmental contaminants, can be extracted from the subsurface environments for recovery (Siegert et al. 2013). However, paraffinic n-alkanes, one of the components of linear alkanes, is generally solid at ambient temperatures, resulting in their difficulties in extraction, transportation and handling which may be tackled by the mechanical or physical means but usually comparatively costly (Azevedo and Teixeira 2003; Burger et al. 1981; Sanjay et al. 1995; Wentzel et al. 2007). Therefore, potential biodegradation from waxy n-alkanes to methane can be an environmentally friendly and effective biotechnology strategy for further energy recovery and utilization tracked from hydrocarbon-contaminated environments (Head et al. 2014).

The inert n-alkanes have been proposed to be initially activated through several alternative enzymatic reactions without oxygen as the reductant (Boll et al. 2018; Mbadinga et al. 2011). Among them, fumarate addition pathway has been proposed to be a predominant activation mechanism used by alkane-degrading bacteria studied so far and degradation is the addition of alkanes across the double bond of fumarate with the formation of alkylsuccinates catalyzed by glycyl radical enzyme (Callaghan et al. 2009, 2008; Cravo-Laureau et al. 2005; Grundmann et al. 2008; Ji et al. 2019; Rabus et al. 2001).

It is not surprising that methanogenic alkane biodegradation requires cooperative interactions of microorganisms including alkane-degrading bacteria, syntrophic bacteria and methanogenic archaea, which has been well reported (Dolfing et al. 2008). To date, although anaerobic microorganisms capable of oxidizing n-alkanes have been isolated or highly enriched from biospheres, information on methanogenic long-chain alkanes degradation remains poorly understood (Boll et al. 2018; Wilkes and Rabus 2018). Actually, (Caldwell et al. 1998) documented anaerobic biodegradation of long-chain C15–C34 n-alkanes from a weathered crude oil within 201-day-incubation inoculated with chronically hydrocarbon-contaminated marine sediments under sulfate-reducing conditions. Similar observation proposed biotransformation of C13–C34 n-alkanes in amendments with weathered oil under both sulfate-reducing and methanogenic conditions by microorganisms derived from an anoxic natural gas condensate-contaminated aquifer, revealing that the availability of exogenous electron acceptor is not a constraint on biodegradation of long-chain n-alkanes (Townsend et al. 2003). The hyperthermophilic sulfate-reducing archaeon, Archaeoglobus fulgidus, was demonstrated to oxidize C10–C21 n-alkanes through addition to fumarate (Khelifi et al. 2014).

With respect to solid n-alkane (> C17) recent studies which used paraffin (n-octacosane) as the sole carbon and energy sources under methanogenic condition enriched from hydrocarbon-contaminated aquifer sediments of low temperature, has proved paraffin degradation coupled with methane generation. Metagenomic analysis proposed that the paraffin molecular was most likely activated via fumarate addition pathway by syntrophic members of Smithella (Oberding and Gieg 2018; Wawrik et al. 2016). Furthermore, it was shown that putative alkylsuccinate synthase (assA) gene was found in paraffin-degrading enrichment cultures derived from hydrocarbon-impacted aquifer sediments, indicative of anaerobic long-chain n-alkane metabolism (Callaghan et al. 2010). Despite the fact that high molecular weight alkanes are solid at room temperature, they actually tend to be melted in the oil phase under high-temperature condition (Etoumi 2007; Sanjay et al. 1995). Thus, long-chain paraffin is theoretically expected to be metabolized by hydrocarbon-degrading consortia and subsequently converted into methane by syntrophic microorganisms and methanogenic archaea in deep subsurface of high temperature (Jones et al. 2008; Oberding and Gieg 2018). Nevertheless, knowledge regarding the anaerobic biodegradation of long-chain paraffin and possible microbial populations in thermophilic cultures under methanogenic conditions remain unclear (Callaghan 2013; Wentzel et al. 2007).

In this work, methanogenic long-chain (C22–C30) n-alkane-degrading enrichment cultures were established using production water of a high-temperature oil reservoir as the inoculum. Measurement of biogenic methane accumulation during more than 2 years of incubation in conjunction with characterization and quantification of residual substrates was performed to assess the potential biodegradability of long-chain n-alkanes. Metabolites and functional genes were also identified through chemical and molecular biological approaches. Other than that, composition and diversity of microbial populations based on Illumina Miseq Sequencing were investigated, for the purpose of exploring the substances conversion and metabolic activities in paraffinic n-alkane-dependent consortia.

Experimental sections

Establishment of methanogenic enrichment culture

Production water (named “BG”) sampled from a high-temperature oil reservoir, from Zhan 3 block of Shengli oilfield in Shandong, China, was used as the inoculum for methanogenic enrichment cultures. Anaerobic experimental incubations were set up in 120 mL of clean and sterile serum bottles, containing 10 mL of autoclaved basal medium and 40 mL of production fluids. The basal medium contained: (g/l): NaCl, 2.0; KCl, 0.5; MgCl2·6H2O, 0.4; NH4Cl, 0.25; CaCl2·2H2O, 0.10; KH2PO4, 0.20; and resazurin, 0.001. And the basal medium was supplemented with 1.0 mL trace elements and 1.0 mL vitamins stock solution, which was described previously (Xu et al. 2019).

A mixture of long-chain n-alkanes (with the purity of 98–99% GC), purchased from TCI, including docosane (C22H46), tetracosane (C24H50), hexacosane (C26H54), octacosane (C28H58) and triacontane (C30H62), was added (40 mg of each compound) as the sole carbon sources, named “E”. Control without additional alkanes (“C”) was prepared to be able to eliminate the contribution of indigenous substrates. Samples at day 322 were named “1”, and samples at day 736 were named “2”. So, “E1” and “E2” represented n-alkane-amended cultures at day 322 and 736; “C1” and “C2” represented substrate-unamended samples at day 322 and 736. Additionally, heat-killed control sterilized for three times were also cultured and amended with a mixture of five alkanes. All experimental incubations in serum bottles flushed with 99.99% N2 were sealed by butyl rubber stopper and aluminum seal to ensure the strictly anaerobic conditions. Each enrichment culture was in quadruplicate and incubated at 55 °C in the dark.

Chemical analysis

The measurement of biogas at intervals in cultures was conducted by a 500-μL gas-tight syringe to withdraw 200 μL of headspace using gas chromatography (GC 9890B), as described previously (Chen et al. 2019).

Quantification of volatile fatty acids (VFAs) was analyzed by ion chromatograph (ICS-1100, USA). For determination of long-chain fatty acids (LCFAs), culture aliquot of E and C were extracted at the incubations of days 322 and 736, the extracted organic solvent soluble fractions were pre-treated and injected onto the Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometer (GC–MS), as previously reported (Liang et al. 2016).

Residual n-alkanes were quantified by additional cetyl chloride and extracted by n-hexane, according to the previous description (Wang et al. 2011). The stoichiometric equations (Symons and Buswell 1933) of n-C22, n-C24, n-C26, n-C28 and n-C30 were used to calculate the maximum theoretical methane yields during 736 days of incubation.

Modified Gompertz model

The methane production was evaluated by the modified Gompertz model (Eq. 6) to indicate the growth of microorganisms (Gu 2016). Assuming that the methane production rate is proportional to microbial activity in enrichment culture, the modified Gompertz model can be used to assess the lag phase, maximum methane yield and methane production rate (Xu et al. 2019).

where Y = accumulative methane production (μmol), A = methane yield potential (μmol), Vmax= the maximum methane production rate (μmol/d), e = natural constant (2.7183), λ = lag phase time (days), t = the incubation time (days). A, K and λ could be estimated based on a statistical model of SGompertz using ORIGINPRO 8.0 software (OriginLab, USA). And Vmax can be estimated by the Eq. (7).

Characterization of microbial communities

Total genomic DNA samples were extracted from 5 mL enrichment cultures at 322 and 736 days in serum bottles following the instruction of AxyPrep™ Bacterial Genomic DNA Miniprep Kit protocol (Axygen Bicosciences, Inc., CA, USA), and stored at − 20 °C prior to further analysis.

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification of bacterial 16S rRNA genes V4–V5 regions was conducted using the primer set 515F (5′-GTGCCAGCMGCCGCGG-3′) and 907R (5′-CCGTCAATTCMTTTRAGTTT-3′), and 344F (5′-ACGGGGYGCAGCAGGCGCGA-3′) and 915R (5′-GTGCTCCCCCGCCAATTCCT-3′) for archaeal 16S rRNA genes. The PCR system and program were previously described (Li et al. 2017). All valid sequences obtained by Illumina Miseq sequencing were clustered into operational taxonomic units (OTUs) using the Silva database. The data of bacteria and archaea were deposited into the NCBI SRA database under the accession number PRJNA545407.

Detection and phylogenetic analysis of mcrA genes

The methyl coenzyme-M reductase subunit alpha (mcrA) genes were amplified by the primer set mlas-mod-F and mcrA-rev-R (Angel et al. 2011). The PCR condition was conducted as follows: initial denaturation at 96 °C for 3 min, followed by 32 cycles of 96 °C for 30 s, 54 °C for 30 s and 72 °C for 45 s, and a final elongation for 10 min at 72 °C. After purifying, cloning and sequencing, valid sequences with more than 96% similarity were classified into operational taxonomic units (OTUs) through CD-HIT Suite and were translated through EMBOSS Transeq Bioinformatics tools. Sequences closely related to the representative OTUs were selected using BLAST in the GenBank database. Phylogenetic trees were constructed using MEGA7.0 software with neighbor-joining method and 1000 bootstrap replicates (Kumar et al. 2016). All raw mcrA gene sequences were submitted to GenBank under the accession numbers MK990831 to MK991144.

Quantitative PCR of mcrA genes

Quantitative PCR of mcrA genes were conducted with the primer set MLF (5′- GGTGGTGTMGGATTCACACARTAYGCWACAGC-3′) and MLR (5′- TTCATTGCRTAGTTWGGRTAGTT -3′) (Luton et al. 2002) by using the SYBR Green I Real-Time PCR with a CFX96 thermocycler (BioRad, USA). The quantitative PCR reaction was performed with a tenfold dilution series of plasmids containing target DNA sequences to establish the standard curve. The qPCR reaction with a volume of 10 μL contained TB Green Premix Ex Taq II (5 μL), Bovine Serum Albumin solution (0.1 μL), each PCR primer (0.2 μL), ddH2O (3.5 μL) and DNA template (1 μL). The conditions were as follows: a pre-denaturation at 95 °C for 3 min, followed by 40 cycles of denaturation at 95 °C for 20 s, annealing at 55 °C for 30 s, elongation at 72 °C for 60 s.

Results

Gas production in enrichment cultures

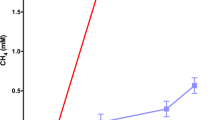

Over the 736 days of incubation, gas sampling in cultures E and C was periodically performed to monitor the accumulation of biogas, including methane, carbon dioxide and hydrogen. Accumulative methane formation and carbon dioxide was exhibited (Fig. 1), while hydrogen was under the detection limit in these two cultures.

Accumulative production of CH4 (a) and CO2 (b) in enrichment cultures amended with long-chain n-alkanes (E) and control cultures without alkanes (C) inoculated with production water during 736-day incubation and the predicted curve of methane production (red line in a) with kinetic parameters using the modified Gompertz model

As shown in Fig. 1a, enhanced methane production was observed in culture E amended with n-alkanes in comparison with that in culture C. After 322 days of incubation, 33 μmol of CH4 was detected in the substrate-free culture (C) and the methane generation then reached a plateau of approximately 43 μmol. By contrast, cultures amended with n-alkanes showed 72 μmol of methane at day 322, and then started to produce significant amount of CH4. A maximum methane production of 1754 μmol was observed in culture E at the end of incubation, suggesting that 1682 μmol of CH4 was generated at the second stage. CO2 started to accumulate at the beginning of the incubation in both cultures (Fig. 1b). Compared with the control sample without n-alkanes, an increasing amount of CO2 was observed in culture E after 322-day incubation, reaching from 128 μmol on day 322 to 427 μmol on day 736. Also, no production of methane and carbon dioxide were detected from the killed control culture (not shown in Fig. 1). The average production rate of methane was 0.12 and 4.06 μmol/d during the first and the second stage, respectively. Interestingly, it was obvious that during the incubation time from day 351 to day 513, the methane was quickly generated (from 142 to 1473 μmol). The measured maximum methane production rate (8.22 μmol/d) was observed at this period. It was estimated that the measured maximum methane yield rate was 164.40 μmol L−1 d−1 resulting from the 50-mL volume of the enrichment culture.

In addition, the predicted kinetic curve of methane production over the whole incubation time based on modified Gompertz modelling, to assess the predicted methane yield and methane production rate, was shown in Fig. 1a. It can be seen that the lag phase (λ) was 353.8 days and the methane yield potential (A) was 1752.54 μmol. According to the Eq. (7), the predicted maximum methane production rate was predicted to be 10.32 μmol/d (206.40 μmol L−1 d−1).

Depletion of n-alkane and detection of intermediate metabolites

At the two stages of anaerobic incubation (day 322 and day 736), control and experimental samples were monitored for residual alkanes and metabolites. The residual alkanes and volatile fatty acids (VFAs) were shown in Fig. 2. Significant depletion of n-alkanes was observed in the culture E at different stages, especially at the second stage. Each added compound was consumed partly (31.3–56.8%) by 322 days and all added n-alkanes were consumed nearly completely (97.3–99.7%) at the end of the incubation. According to stoichiometric Eqs. (1–5), the consumption of n-alkanes during the incubation period were predicted to generate 10.09 mmol methane, which hence suggested the measured CH4 yield accumulated in headspace (1680.03 μmol) accounted for 16.7% of the theoretical value at 736 days (Additional file 1: Table S1).

No putative alkylsuccinates, which is the production of alkane addition to fumarate, were detected in any cultures, and this is probably due to their extremely slow microbial transformation and low steady state (Oberding and Gieg 2018). Neither did other putative bio-signature metabolites involved in other enzymatic activation mechanisms such as hydroxylation and carboxylation pathways. However, dicarboxylic acids (ranging from C4 to C12) that are probably involved in pathways downstream of fumarate addition can be found in n-alkane-amended samples except for C11 in E1 sample, and their mass spectra were shown in Additional file 1: Fig. S1.

Diversity of microbial community composition

To study bacterial communities in the samples, over 35,000 valid sequences were acquired from Illumina Miseq sequencing for each sample (BG, E1, E2, C1 and C2). The relative abundance of quality sequences at the phylum level identified in these samples were used for bacterial community analysis shown as bubble plot (Additional file 1: Fig. S2). At the phylum level, the most abundant phylum in the inoculum sample and incubated samples were different. Among all bacteria in BG, sequences belonging to the phylum Proteobacteria were the most abundant group which represented nearly 90% of all valid sequences, and Actinobacteria and Bacteroidetes accounted for approximately 1.0% and 8.0%, respectively. Minor members in BG includes Firmicutes, Acetothermia, Chloroflexi and Aminicenantes (a total of less than 0.1%). It is evident that a decreasing relative abundance in Proteobacteria was detected in enrichment cultures compared with the BG. In culture C, the phylum Firmicutes contributed the most abundant taxa in culture C, constituting around 45.7% and 56.6% of all sequences in samples C1 and C2. Members of Proteobacteria showed the second highest relative abundance, comprising 39.0% and 36.4% at day 322 and 736, respectively. Interestingly, there was an obvious increase in the relative abundance of Actinobacteria in treatment E amended with n-alkanes during the incubation period. The relative abundance of sequences from this phylum increased from 20.2% of E1 to 55.8% of E2, which made Actinobacteria the dominant bacteria in culture E.

For archaeal communities, more than 30,000 high-quality sequences were obtained for each sample after 322 and 736 days of anaerobic incubation and were classified at the genus level. As shown in Additional file 1: Fig. S3, the dominant member in the inoculum sample and substrate-unamended control culture was Methanothermobacter, comprising 78.7% in BG, 98.5% in culture C1 and 90.8% in culture C2. While in culture E, the most abundant taxa shifted from Methanothermobacter at day 322 (49.0%) to sequences belonging to the order Thermoplasmatales at day 736 (71.0%).

Phylogenetic analysis and quantification of mcrA genes

75, 83, 82 and 74 (in total of 314) mcrA sequences were recovered from cultures E1, E2, C1 and C2, respectively. All mcrA gene clones were grouped into 17 OTUs for phylogenetic analysis. As can be seen from the phylogenetic tree (Fig. 3), 17 OTUs could be classified into four different orders including Methanomicrobiales (in purple background), Methanomassiliicoccus (in yellow background), Methanosarcinales (in green background) and Methanoabcteriales (in red background). It was shown that over time, the diversity of predominant mcrA gene group increased in n-alkane-amended culture, but sequences of the order Methanobacteriales was still the dominant group of mcrA gene in each sample. Clone sequences belonging to the order of Methanosarcinales in cultures E1 (21.3%) and E2 (19.3%) were all affiliated with Methanosaeta. Representative OTUs E1_63 and E2_23 accounted for 1.3% and 12.0% of respective total sequences, closely related to mcrA sequences of Methanomassiliicoccus, which was not detected in results of the archaeal 16S rRNA gene.

The qPCR analysis of mcrA gene indicated that gene abundance (gene copies per microliter of culture aliquot) of mcrA gene in E1, E2, C1 and C2 were 25.05, 1.63 × 104, 20.67 and 16.92 (copies/μL), respectively (shown in Fig. 4). Obviously, n-alkane-degrading enrichment culture at the end of the incubation (the treatment E2) was detected with the most mcrA gene copies, which was consistent with the profile of methane production.

Discussion

Methanogenic biodegradation in C22–C30 n-alkane-dependent cultures

n-Alkanes have been reported to be converted to methane facilitated by microbial degradation under anoxic condition (Zengler et al. 1999). Having been studied for decades, the ubiquitous presence of methanogenic biotransformation of residual hydrocarbons promotes them to be important roles in the process of hydrocarbon contaminants conversion and recovery (Head et al. 2014). Despite increasing evidence that supports the potential of anaerobic microbial biodegradation of long-chain n-alkanes, the degradation of paraffinic n-alkanes is still considered challenging for microorganisms due to their insolubility at room temperature (Boll et al. 2018; Jimenez et al. 2016; Wilkes and Rabus 2018).

In the current study, a significant accumulation of methane can be observed in the long-chain n-alkane-dependent consortium derived from a high-temperature petroleum reservoir production water over a long term of approximately 2 years of anaerobic incubation. Combined with the almost complete consumption of added n-alkanes in experimental group (Fig. 2), microbial communities in E cultures were suggested to have the capability to degrade C22–C30 n-alkanes to methane, which is consistent with the research that paraffinic alkanes as the sole substrates could be converted to methane by a low-temperature methanogenic consortium enriched from hydrocarbon-contaminated aquifer sediments (Wawrik et al. 2016).

Furthermore, the detection of other metabolites including VFAs and dicarboxylic acids in n-alkane-amended cultures indicated that long-chain n-alkanes were probably metabolized to acids by anaerobic consortium and finally converted to methane and carbon dioxide. This proposed mechanism is similar to that which has been proposed for hexadecane degradation (Embree et al. 2014). Similar observation was reported in a methanogenic waxy hydrocarbon-degrading consortium from freshwater hydrocarbon-impacted aquifer sediments, where the consumption of n-octacosane (C28) was coupled with methane production and detection of several dicarboxylic acids (Oberding and Gieg 2018).

Microbial populations acclimatize to long-chain n-alkanes over time

Methane was quickly formed and the culture rapidly reached the maximum methane production after initial active methanogenesis. Recent studies have demonstrated that the extent of microbial degradation of heavier n-alkanes is larger than that of lighter ones under anoxic condition (Cheng et al. 2014, 2019; Hasinger et al. 2012; Mishra et al. 2017). Added n-alkanes were consumed almost completely (97.3–99.7%) by the end of the cultivation, but theoretical methane production was relatively low (Additional file 1: Table S1). Hence, further transfer enrichments are expected to obtain the determination and quantification of metabolites to address the metabolic fate of paraffin.

As indicated by amplicon survey and qPCR analysis of mcrA functional gene, the relative abundance of mcrA gene in cultures amended with paraffinic n-alkanes increased significantly from day 322 to day 736. It is likely that hydrogentrophic methaogenesis may become the major methanogenic pathway, as suggested by phylogenetic analysis of mcrA genes (Fig. 3), which presented the highest abundance of Methanothermobacter in alkane-degrading cultures, especially in E2 (Khelifi et al. 2014; Mayumi et al. 2011).

In addition, a clear variation of microbial community structure was observed during the nearly two-year-incubation period, also indicating an acclimatization to the long-chain n-alkanes over the cultivation (Liang et al. 2016). The evident that higher frequency of the phylum Actinobacteria in long-chain n-alkane-dependent cultures after a long period of anaerobic incubation may suggest a potential role in the conversion of C22–C30 n-alkanes to methane (Additional file 1: Fig. S2). Although members of Actinobacteria were widely known for aerobic respiration (Barka et al. 2016; Kunapuli et al. 2007), they were observed in other anoxic hydrocarbon-degrading cultures (Mbadinga et al. 2012; Wang et al. 2012; Xu et al. 2019), and identified to be major phylogenetic groups in anaerobic bisphenol A degrading sediments (Yang et al. 2015) and were hypothesized to participate in methanogenic glucose degradation in anaerobic digester sludge (Ito et al. 2012). Besides, the phylum Actinobacteria was implicated to utilize secondary substrates or dead biomass as the primary syntrophs in an iron-reducing benzene-degrading enrichment culture with the help of stable isotope probing (Kunapuli et al. 2007). Accordingly, the absolute dominance of the phylum Actinobacteria probably suggested their involvement in the microbial metabolism from waxy n-alkanes to methane. Nevertheless, additional further study is required to explore the crucial players and active microorganisms in high-temperature long-chain alkane-degrading cultures.

Putative paraffin degradation pathway in thermophilic methanogenic paraffin-dependent enrichments

Recent functional information and chemical and metagenomic analysis of methanogenic paraffin biodegradation indicated that n-octacosane can be initially activated to alkylsuccinates via the fumarate addition pathway by uncultured members of Smithella in n-alkane-degrading consortia, retrieved from low-temperature fuel-contaminated aquifer sediments (Callaghan et al. 2010; Wawrik et al. 2016). However, in this study, the predominant bacterial members in C22–C30 n-alkane-dependent cultures were affiliated to Actinobacteria, and members of Actinobacteria were not known for anaerobic alkane biodegradation. To further verify the lack of canonical assA genes in our samples, we utilized more than ten previously designed sets of different primers targeting canonical assA genes with a broad diversity (Abu Laban et al. 2015; Callaghan et al. 2010; Gittel et al. 2015; von Netzer et al. 2013). However, no amplicons could be retrieved here, implying that either there lack such genes in the consortia, or the assA genes here are too diverse to be targeted by the primers that we used (Cheng et al. 2019). Although no alkylsuccinate-like metabolites were acquired from the samples, dicarboxylic acids were detected only in long-chain n-alkane-amended cultures. According to previously postulated mechanism (Oberding and Gieg 2018), in which both ends of paraffin can be activated by the fumarate addition pathway. Future studies such as the design of new and universal primers as well as SIP techniques (Cheng et al. 2013; Jimenez et al. 2016; Kleindienst et al. 2014; Kunapuli et al. 2007) are required to unravel the exact activation mechanisms of paraffin.

On the other hand, other possible enzymatic activation pathways including hydroxylation, carboxylation, formation of alkyl-coenzyme-M and ‘intra hydroxylation’ oxidation should not be overlooked (Callaghan et al. 2009; Heider and Schühle 2013; Laso-Pérez et al. 2016; Rabus and Heider 1998; Zedelius et al. 2011). Similar observations were made in a methanogenic consortium enriched from Shengli oilfield amended with heavy oil (Cheng et al. 2019). Since there still remained uncertain with respect to the key active microorganisms and activation pathways in this work, more microbial and functional information are expected to be explored via omics-based sequencings and other chemical techniques (Gieg and Toth 2016; von Netzer et al. 2018). And also, there may exist novel pathway documented recently based on metagenomics analysis (Liu et al. 2019).

The current available information about biotransformation of paraffin in thermophilic anoxic environments is limited. In this work, we obtained a methanogenic long-chain (C22–C30) n-alkane-degrading enrichment culture inoculated from production water of a high-temperature oil reservoir. Significant production of methane and almost complete consumption of substrates in n-alkane-amended cultures indicated that substrates consumption was coupled to methane production. Additionally, high-throughput sequencing analysis suggested that members of Actinobacteria turned to be predominant in n-alkane-amended cultures after 736 days of incubation. However, active microorganisms and metabolic pathways require further evidence, probably by using metagenomics and metatranscriptomics sequencing and stable isotope probing techniques. These observations enriched our current knowledge of metabolic processes in anaerobic biodegradation of paraffinic alkanes under high-temperature conditions.

Availability of data and materials

Raw data for microbial community sequencing and mcrA genes sequences are available in the GenBank archive at the National Center for Biotechnological Information (NCBI) as listed in the manuscript.

Abbreviations

- assA :

-

Alkylsuccinate synthase gene

- mcrA :

-

Methyl coenzyme-M reductase gene

- BG:

-

Production water as an inoculum

- E1:

-

n-Alkane-amended cultures at day 322

- E2:

-

n-Alkane-amended cultures at day 736

- C1:

-

Substrate-unamended cultures at day 322

- C2:

-

Substrate-unamended cultures at day 736

References

Abu Laban N, Dao A, Semple K, Foght J (2015) Biodegradation of C7 and C8 iso-alkanes under methanogenic conditions. Environ Microbiol 17:4898–4915. https://doi.org/10.1111/1462-2920.12643

Angel R, Claus P, Conrad R (2011) Methanogenic archaea are globally ubiquitous in aerated soils and become active under wet anoxic conditions. ISME J 6:847–862. https://doi.org/10.1038/ismej.2011.141

Azevedo L, Teixeira A (2003) A critical review of the modeling of wax deposition mechanisms. Pet Sci Technol 21:393–408. https://doi.org/10.1081/LFT-120018528

Barka EA, Vatsa P, Sanchez L, Gaveau-Vaillant N, Jacquard C, Meier-Kolthoff JP, Klenk HP, Clement C, Ouhdouch Y, van Wezel GP (2016) Taxonomy, physiology, and natural products of Actinobacteria. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 80:1–43. https://doi.org/10.1128/MMBR.00019-15

Boll M, Estelmann S, Heider J (2020) Anaerobic degradation of hydrocarbons: mechanisms of hydrocarbon activation in the absence of oxygen Anaerobic utilization of hydrocarbons, oils and lipids. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-50391-2_2

Burger E, Perkins T, Striegler J (1981) Studies of wax deposition in the trans Alaska pipeline. J Pet Technol 33:1–075. https://doi.org/10.2118/8788-pa

Caldwell ME, Garrett RM, Prince RC, Suflita JM (1998) Anaerobic biodegradation of long-chain n-alkanes under sulfate-reducing conditions. Environ Sci Technol 32:2191–2195. https://doi.org/10.1021/es9801083

Callaghan AV (2013) Enzymes involved in the anaerobic oxidation of n-alkanes: from methane to long-chain paraffins. Front Microbiol 4:89. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2013.00089

Callaghan AV, Wawrik B, Ni Chadhain SM, Young LY, Zylstra GJ (2008) Anaerobic alkane-degrading strain AK-01 contains two alkylsuccinate synthase genes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 366:142–148. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.11.094

Callaghan AV, Tierney M, Phelps CD, Young LY (2009) Anaerobic biodegradation of n-hexadecane by a nitrate-reducing consortium. Appl Environ Microbiol 75:1339–1344. https://doi.org/10.1128/aem.02491-08

Callaghan AV, Davidova IA, Savage-Ashlock K, Parisi VA, Gieg LM, Suflita JM, Kukor JJ, Wawrik B (2010) Diversity of benzyl-and alkylsuccinate synthase genes in hydrocarbon-impacted environments and enrichment cultures. Environ Sci Technol 44:7287–7294. https://doi.org/10.1021/es1002023

Chen J, Liu YF, Zhou L, Mbadinga SM, Yang T, Zhou J, Liu JF, Yang SZ, Gu JD, Mu BZ (2019) Methanogenic degradation of branched alkanes in enrichment cultures of production water from a high-temperature petroleum reservoir. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 103:2391–2401. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00253-018-09574-1

Cheng L, Ding C, Li Q, He Q, Dai LR, Zhang H (2013) DNA-SIP reveals that Syntrophaceae play an important role in methanogenic hexadecane degradation. PLoS ONE 8:e66784. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0066784

Cheng L, Shi S, Li Q, Chen J, Zhang H, Lu Y (2014) Progressive degradation of crude oil n-alkanes coupled to methane production under mesophilic and thermophilic conditions. PLoS ONE 9:e113253. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0113253

Cheng L, Sb Shi, Yang L, Zhang Y, Dolfing J, Yg Sun, Ly Liu, Li Q, Tu B, Lr Dai, Shi Q, Zhang H (2019) Preferential degradation of long-chain alkyl substituted hydrocarbons in heavy oil under methanogenic conditions. Org Geochem. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.orggeochem.2019.103927

Cravo-Laureau C, Grossi V, Raphel D, Matheron R, Hirschler-Rea A (2005) Anaerobic n-alkane metabolism by a sulfate-reducing bacterium, Desulfatibacillum aliphaticivorans strain CV2803T. Appl Environ Microbiol 71:3458–3467. https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.71.7.3458-3467.2005

Dolfing J, Larter SR, Head IM (2008) Thermodynamic constraints on methanogenic crude oil biodegradation. ISME J 2:442–452. https://doi.org/10.1038/ismej.2007.111

Embree M, Nagarajan H, Movahedi N, Chitsaz H, Zengler K (2014) Single-cell genome and metatranscriptome sequencing reveal metabolic interactions of an alkane-degrading methanogenic community. ISME J 8:757–767. https://doi.org/10.1038/ismej.2013.187

Etoumi A (2007) Microbial treatment of waxy crude oils for mitigation of wax precipitation. J Pet Sci Eng 55:111–121. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.petrol.2006.04.015

Gieg LM (2018) Microbial communities in oil shales, biodegraded and heavy oil reservoirs, and bitumen deposits microbial communities utilizing hydrocarbons and lipids: members, metagenomics and ecophysiology. Springer, Cham, pp 1–21

Gieg LM, Toth CRA (2016) Anaerobic biodegradation of hydrocarbons: metagenomics and metabolomics Consequences of microbial interactions with hydrocarbons, oils, and lipids: biodegradation and bioremediation. Springer, Cham, pp 1–42

Gittel A, Donhauser J, Røy H, Girguis PR, Jørgensen BB, Kjeldsen KU (2015) Ubiquitous presence and novel diversity of anaerobic alkane degraders in cold marine sediments. Front Microbiol 6:1414. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2015.01414

Grundmann O, Behrends A, Rabus R, Amann J, Halder T, Heider J, Widdel F (2008) Genes encoding the candidate enzyme for anaerobic activation of n-alkanes in the denitrifying bacterium, strain HxN1. Environ Microbiol 10:376–385. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1462-2920.2007.01458.x

Gu JD (2016) More than simply microbial growth curves. Appl Environ Biotechnol. https://doi.org/10.18063/aeb.2016.02.007

Hasinger M, Scherr KE, Lundaa T, Brauer L, Zach C, Loibner AP (2012) Changes in iso- and n-alkane distribution during biodegradation of crude oil under nitrate and sulphate reducing conditions. J Biotechnol 157:490–498. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbiotec.2011.09.027

Head IM, Gray ND, Larter SR (2014) Life in the slow lane; biogeochemistry of biodegraded petroleum containing reservoirs and implications for energy recovery and carbon management. Front Microbiol 5:566. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2014.00566

Heider J, Schühle K (2013) Anaerobic biodegradation of hydrocarbons including methane The Prokaryotes. Springer, Berlin, pp 605–634

Wilkes H, Rabus R (2018) Catabolic pathways involved in the anaerobic degradation of saturated hydrocarbons Anaerobic utilization of hydrocarbons, oils, and lipids. Springer, Cham, pp 1–24

Ito T, Yoshiguchi K, Ariesyady HD, Okabe S (2012) Identification and quantification of key microbial trophic groups of methanogenic glucose degradation in an anaerobic digester sludge. Bioresour Technol 123:599–607. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biortech.2012.07.108

Ji JH, Liu YF, Zhou L, Mbadinga SM, Pan P, Chen J, Liu JF, Yang SZ, Sand W, Gu JD, Mu BZ (2019) Methanogenic degradation of long n-alkanes requires fumarate-dependent activation. Appl Environ Microbiol. https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.00985-19

Jimenez N, Richnow HH, Vogt C, Treude T, Kruger M (2016) Methanogenic hydrocarbon degradation: evidence from field and laboratory studies. J Mol Microbiol Biotechnol 26:227–242. https://doi.org/10.1159/000441679

Jones DM, Head IM, Gray ND, Adams JJ, Rowan AK, Aitken CM, Bennett B, Huang H, Brown A, Bowler BF, Oldenburg T, Erdmann M, Larter SR (2008) Crude-oil biodegradation via methanogenesis in subsurface petroleum reservoirs. Nature 451:176–180. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature06484

Khelifi N, Amin Ali O, Roche P, Grossi V, Brochier-Armanet C, Valette O, Ollivier B, Dolla A, Hirschler-Rea A (2014) Anaerobic oxidation of long-chain n-alkanes by the hyperthermophilic sulfate-reducing archaeon, Archaeoglobus fulgidus. ISME J 8:2153–2166. https://doi.org/10.1038/ismej.2014.58

Kleindienst S, Herbst F-A, Stagars M, von Netzer F, von Bergen M, Seifert J, Peplies J, Amann R, Musat F, Lueders T, Knittel K (2014) Diverse sulfate-reducing bacteria of the Desulfosarcina/Desulfococcus clade are the key alkane degraders at marine seeps. ISME J 8:2029–2044. https://doi.org/10.1038/ismej.2014.51

Kumar S, Stecher G, Tamura K (2016) MEGA7: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 7.0 for bigger datasets. Mol Biol Evol 33:1870–1874. https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msw054

Kunapuli U, Lueders T, Meckenstock RU (2007) The use of stable isotope probing to identify key iron-reducing microorganisms involved in anaerobic benzene degradation. ISME J 1:643–653. https://doi.org/10.1038/ismej.2007.73

Laso-Pérez R, Wegener G, Knittel K, Widdel F, Harding KJ, Krukenberg V, Meier DV, Richter M, Tegetmeyer HE, Riedel D, Richnow HH, Adrian L, Reemtsma T, Lechtenfeld OJ, Musat F (2016) Thermophilic archaea activate butane via alkyl-coenzyme M formation. Nature 539:396–401. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature20152

Li XX, Liu JF, Zhou L, Mbadinga SM, Yang SZ, Gu JD, Mu BZ (2017) Diversity and composition of sulfate-reducing microbial communities based on genomic DNA and RNA transcription in production water of high temperature and corrosive oil reservoir. Front Microbiol 8:1011. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2017.01011

Liang B, Wang LY, Zhou Z, Mbadinga SM, Zhou L, Liu JF, Yang SZ, Gu JD, Mu BZ (2016) High frequency of Thermodesulfovibrio spp. and Anaerolineaceae in association with Methanoculleus spp. in a long-term incubation of n-alkanes-degrading methanogenic enrichment culture. Front Microbiol 7:1431. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2016.01431

Liu YF, Qi ZZ, Shou LB, Liu JF, Yang SZ, Gu JD, Mu BZ (2019) Anaerobic hydrocarbon degradation in candidate phylum ‘Atribacteria’ (JS1) inferred from genomics. ISME J 13:2377–2390. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41396-019-0448-2

Luton PE, Wayne JM, Sharp RJ, Riley PW (2002) The mcrA gene as an alternative to 16S rRNA in the phylogenetic analysis of methanogen populations in landfillb. Microbiology 148:3521–3530. https://doi.org/10.1099/00221287-148-11-3521

Mayumi D, Mochimaru H, Yoshioka H, Sakata S, Maeda H, Miyagawa Y, Ikarashi M, Takeuchi M, Kamagata Y (2011) Evidence for syntrophic acetate oxidation coupled to hydrogenotrophic methanogenesis in the high-temperature petroleum reservoir of Yabase oil field (Japan). Environ Microbiol 13:1995–2006. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1462-2920.2010.02338.x

Mbadinga SM, Wang LY, Zhou L, Liu JF, Gu JD, Mu BZ (2011) Microbial communities involved in anaerobic degradation of alkanes. Int Biodeterior Biodegrad 65:1–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibiod.2010.11.009

Mbadinga SM, Li KP, Zhou L, Wang LY, Yang SZ, Liu JF, Gu JD, Mu BZ (2012) Analysis of alkane-dependent methanogenic community derived from production water of a high-temperature petroleum reservoir. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 96:531–542. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00253-011-3828-8

Mishra S, Wefers P, Schmidt M, Knittel K, Kruger M, Stagars MH, Treude T (2017) Hydrocarbon degradation in caspian sea sediment cores subjected to simulated petroleum seepage in a newly designed system. Front Microbiol 8:763. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2017.00763

Oberding LK, Gieg LM (2018) Methanogenic paraffin biodegradation: alkylsuccinate synthase gene quantification and dicarboxylic acid production. Appl Environ Microbiol 84:e01773-17. https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.01773-17

Rabus R, Heider J (1998) Initial reactions of anaerobic metabolism of alkylbenzenes in denitrifying and sulfate-reducing bacteria. Arch Microbiol 170:377–384. https://doi.org/10.1007/s002030050656

Rabus R, Wilkes H, Behrends A, Armstroff A, Fischer T, Pierik AJ, Widdel F (2001) Anaerobic initial reaction of n-alkanes in a denitrifying bacterium: evidence for (1-methylpentyl)succinate as initial product and for involvement of an organic radical in n-hexane metabolism. J Bacteriol 183:1707–1715. https://doi.org/10.1128/JB.183.5.1707-1715.2001

Rabus R, Boll M, Heider J, Meckenstock RU, Buckel W, Einsle O, Ermler U, Golding BT, Gunsalus RP, Kroneck PMH, Krüger M, Lueders T, Martins BM, Musat F, Richnow HH, Schink B, Seifert J, Szaleniec M, Treude T, Ullmann GM, Vogt C, von Bergen M, Wilkes H (2016) Anaerobic microbial degradation of hydrocarbons: from enzymatic reactions to the environment. J Mol Microbiol Biotechnol 26:5–28. https://doi.org/10.1159/000443997

Sanjay M, Simanta B, Kulwant S (1995) Paraffin problems in crude oil production and transportation: a review. SPE Prod Facil 10:50–54. https://doi.org/10.2118/28181-PA

Siegert M, Sitte J, Galushko A, Krüger M (2013) Starting up microbial enhanced oil recovery Geobiotechnology II. Springer, pp 1-94

Symons G, Buswell A (1933) The methane fermentation of carbohydrates. J Am Chem Soc 55:2028–2036. https://doi.org/10.1021/ja01332a039

Townsend GT, Prince RC, Suflita JM (2003) Anaerobic oxidation of crude oil hydrocarbons by the resident microorganisms of a contaminated anoxic aquifer. Environ Sci Technol 37:5213–5218. https://doi.org/10.1021/es0264495

von Netzer F, Pilloni G, Kleindienst S, Kruger M, Knittel K, Grundger F, Lueders T (2013) Enhanced gene detection assays for fumarate-adding enzymes allow uncovering of anaerobic hydrocarbon degraders in terrestrial and marine systems. Appl Environ Microbiol 79:543–552. https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.02362-12

von Netzer F, Granitsiotis MS, Szalay AR, Lueders T (2018) Next-generation sequencing of functional marker genes for anaerobic degraders of petroleum hydrocarbons in contaminated environments Anaerobic Utilization of Hydrocarbons, Oils, and Lipids. Springer, Cham, pp 1–20

Wang LY, Gao CX, Mbadinga SM, Zhou L, Liu JF, Gu JD, Mu BZ (2011) Characterization of an alkane-degrading methanogenic enrichment culture from production water of an oil reservoir after 274 days of incubation. Int Biodeterior Biodegrad 65:444–450. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibiod.2010.12.010

Wang LY, Li W, Mbadinga SM, Liu JF, Gu JD, Mu BZ (2012) Methanogenic microbial community composition of cily sludge and its enrichment amended with alkanes incubated for over 500 days. Geomicrobiol J 29:716–726. https://doi.org/10.1080/01490451.2011.619634

Wawrik B, Marks CR, Davidova IA, McInerney MJ, Pruitt S, Duncan KE, Suflita JM, Callaghan AV (2016) Methanogenic paraffin degradation proceeds via alkane addition to fumarate by ‘Smithella’ spp. mediated by a syntrophic coupling with hydrogenotrophic methanogens. Environ Microbiol 18:2604–2619. https://doi.org/10.1111/1462-2920.13374

Wentzel A, Ellingsen TE, Kotlar HK, Zotchev SB, Throne-Holst M (2007) Bacterial metabolism of long-chain n-alkanes. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 76:1209–1221. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00253-007-1119-1

Xu D, Zhang K, Li BG, Mbadinga SM, Zhou L, Liu JF, Yang SZ, Gu JD, Mu BZ (2019) Simulation of in situ oil reservoir conditions in a laboratory bioreactor testing for methanogenic conversion of crude oil and analysis of the microbial community. Int Biodeterior Biodegrad 136:24–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibiod.2018.10.007

Yang Y, Wang Z, He T, Dai Y, Xie S (2015) Sediment bacterial communities associated with anaerobic biodegradation of bisphenol A. Microb Ecol 70:97–104. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00248-014-0551-x

Zedelius J, Rabus R, Grundmann O, Werner I, Brodkorb D, Schreiber F, Ehrenreich P, Behrends A, Wilkes H, Kube M, Reinhardt R, Widdel F (2011) Alkane degradation under anoxic conditions by a nitrate-reducing bacterium with possible involvement of the electron acceptor in substrate activation. Environ Microbiol Rep 3:125–135. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1758-2229.2010.00198.x

Zengler K, Richnow HH, Rosselló-Mora R, Michaelis W, Widdel F (1999) Methane formation from long-chain alkanes by anaerobic microorganisms. Nature 401:266. https://doi.org/10.1038/45777

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the management of Shengli Oilfield for sampling support.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grants No. 41530318, 41373070, 41807324), NSFC/RGC Joint Research Fund (No. 41161160560), the Shanghai International Collaboration Program (18230743300), the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (No. 222201817017, 50321101917017, 22221818014) and the Research Program of State Key Laboratory of Bioreactor Engineering.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JC conducted experiments assisted by YFL and LZ. JC wrote the manuscript by all co-authors. JC, BZM and JDG designed the study. LZ, MI, SMM, ZWH, WL and XLW assisted JC and YFL on statistical analysis and in the discussion on the interpretation of the data. JFL and SZY were committed to all the experiments. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1: Table S1.

Predicted and measured methane (CH4) yield from enrichment cultures amended with n-alkane mixtures incubated after 322 and 736 days. Fig. S1. Mass spectral profiles of dicarboxylic acids identified in (A) E1 and (B) E2 cultures (Diethyl esterification derivatives). Fig. S2. Bubble plot of bacteria at the phylum level showing the relative abundance in enrichment cultures after incubations (BG: inoculum; E1 and E2: n-alkanes-amended cultures at day 322 and 736; C1 and C2: un-amended samples at day 322 and 736; Red: < 30%; Yellow: 30–80%; Green: ≥ 80%). Fig. S3. Bubble plot of archaea at the genus level showing the relative abundance in enrichment cultures after incubations (BG: inoculum; E1 and E2: n-alkanes-amended cultures at day 322 and 736; C1 and C2: un-amended samples at day 322 and 736; Red: < 30%; Yellow: 30–80%; Green: ≥ 80%).

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, J., Liu, YF., Zhou, L. et al. Long-chain n-alkane biodegradation coupling to methane production in an enriched culture from production water of a high-temperature oil reservoir. AMB Expr 10, 63 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13568-020-00998-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13568-020-00998-5