Abstract

The fruitful association of quantum and integrated photonics holds the promise to produce, manipulate, and detect quantum states of light using compact and scalable systems. Integrating all the building blocks necessary to produce high-quality photonic entanglement in the telecom-wavelength range out of a single chip remains a major challenge, mainly due to the limited performance of on-chip light rejection filters. We report a stand-alone, telecom-compliant device that integrates, on a single substrate, a nonlinear photon-pair generator and a passive pump-rejection filter. Using standard channel-grid fiber demultiplexers, we demonstrate the first entanglement qualification of such an integrated circuit, showing the highest raw quantum interference visibility for time-energy entangled photons over two telecom-wavelength bands. Genuinely pure, maximally entangled states can therefore be generated thanks to the high-level of noise suppression obtained with the pump filter. These results will certainly further promote the development of more advanced and scalable photonic-integrated quantum systems compliant with telecommunication standards.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Quantum information science (QIS) exploits the fundamental properties of quantum physics to code and manipulate quantum states. QIS is regarded as the most promising pathway towards disruptive technologies, envisioning major improvements in processing capabilities and communication security1,2. However, practical implementations, such as quantum key distribution systems or quantum processors, require a large amount of compatible building blocks3,4,5,6. Integrated photonics provide efficient and reliable solutions for realizing advanced quantum communication systems based on both linear and nonlinear elements7,8,9,10,11,12,13. Still, all these realizations face a crucial limitation as soon as on-chip suppression of photonic noise is concerned due to the substantially higher pump intensity compared with that of the photon pairs. Most of the time, this operation is externalized, using fiber or bulk optical components, and hinders the benefit of both the compactness and stability of the whole system14.

Complementary Metal Oxide Semiconductor (CMOS)-compatible technologies hold the promise of bringing quantum photonics one step further with optical circuits showing higher integration levels15. A few experiments based on this technology have been carried out to address the pump-rejection challenge using on-chip solutions16,17,18,19,20,21,22. On-chip pump rejection has been demonstrated based on a semiconductor quantum dot integrated in a CMOS photonic circuit, but emitting out of the telecom range. The other strategies suffer from two main limitations as follows: (i) the continuous monitoring of the filter response to maintain proper performance16,17,18 and (ii) prohibitive additional interconnection losses between components19,20 (up to 9 dB21). Moreover, all these solutions have reported temporal correlation measurements for revealing the degree of indistinguishability between the paired photons19,20. Qualifying quantum correlations in a stricter way, i.e., by means of a Bell-type entanglement witness23, is essential for a large variety of quantum applications such as secret key distribution24, superdense coding25, teleportation26, sensing27, and computing5. Such an entanglement characterization still remains unanswered whatever the integration platform (silicon, III–V semiconductors, lithium niobate) exploited for stand-alone devices embedding a pump-rejection solution. Yet, the degree of entanglement could be reduced by excess background noise or Raman photons induced inside the on-chip pump filter (PF) itself.

In this work, we demonstrate and qualify a wavelength multiplexed entangled photon-pair source fully compliant with fiber telecom networks and semiconductor technology. Based on CMOS-compatible silicon photonics platform, our design includes a photon-pair generator and a pump-rejection filter, paving the way for compact, low-cost, and telecom-compliant quantum solutions. The rejection filter strategy has already shown in a previous work a pump suppression level up to 80 dB28. Moreover, we proceed to the qualification of energy-time entanglement carried by the photon pairs using a standard Franson-type interferometer29. We show two-photon interference fringes with a raw visibility exceeding 92% over 11 complementary channel pairs spanning from both S and C telecom bands30 along with a coincidence-to-accidental ratio reaching 60. By complementary, we understand frequency-correlated channels apart from the pump channel. The next step will consist in integrating wavelength demulitiplexing components directly on chip so as to obtain a fully functionalized and scalable entanglement supplier31.

Results

Photonic device and classical measurements

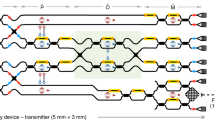

As sketched in Fig. 1a, our silicon chip integrates several building blocks towards realizing a stand-alone quantum photonic device: a ring resonator (RR), a PF based on multi-mode cascaded Bragg filter (BF), and modal couplers, as well as in and out grating couplers. The quality factor and the free spectral range (FSR) of the RR are equal to Q = 3 × 104 and 200 GHz around 1535 nm, respectively. As shown in Fig. 2a, the transmission profile of our RR features by design a frequency-comb structure matching that of the two first telecom channel pairs (see Methods for the design and the fabrication). This makes it possible to use off-the-shelves telecom components for demultiplexing and routing the information out of the chip. Through spontaneous four-wave mixing (SFWM), photon pairs are created according to the conservation of both the energy and the momentum. The photon pairs are produced in a symmetrical way with respect to the pump wavelength (Fig. 2a, b). In the following, long-wavelength photons are referred to as signal photons, whereas short-wavelength ones to as idler photons. Concerning the PF, the grating period of the BFs has been chosen to reflect light around 1535 nm into the second-order mode (see Methods). By adding a single-mode waveguide between the sections of the PF, the second mode is radiated into the substrate, breaking the coherence that would otherwise have been established. This strategy allows to implement high-rejection filters being all-passive, thanks to the cascading of modal-engineered Bragg gratings with relaxed fabrication requirements28.

a Input laser with associated filter (TF) rejecting the amplified spontaneous emission and a polarization controller (PC). Laser light is injected in the ring resonator (RR) through the grating coupler and then propagates to a modal coupler (MC) and through the integrated pump filter (PF). b Schematic top view of one of the cascaded Bragg filter (BF) composing the PF. The output of the chip is connected to either a coincidence setup (c) with a beam splitter (BS) and bandpass filters to demultiplex signal and idler photons (TF signal/idler) or to the entanglement qualification setup (d) in a folded-Franson configuration. e Spectrum of the signal and idler filters, which exhibit 22 dB and 25 dB rejection for the two-FSR shift and three-FSR shift configurations, respectively.

a Scan of the output port of the chip and the feedback port, which represents the portion of light reflected by the first section of the filter. The filter exhibits a rejection of 60 dB (limited by the noise floor of the detector). b Zoom over the pumped resonance of the ring. As can be seen, it corresponds to the center of the pump filter and its 3 dB bandwidth is 42 ± 0.5 pm. Signal, idler, and pumped resonances used in the experiments are highlighted, in red the two-FSR shift, blue the three-FSR shift, and green being the pumped resonance.

A modal coupler is added between the ring and the first Bragg section to recover part of the reflected light through the feedback port32. This makes the alignment of the pump laser to the desired resonance easier even with thermal drift. It is noteworthy that no cladding is added to improve the natural transverse magnetic (TM) polarization filtering of the waveguide. Finally, subwavelength fiber-chip grating couplers are employed to inject and extract transverse electric (TE) polarized light using standard single-mode optical fibers33.

Prior to quantum qualification, we characterize the circuit in the classical regime by measuring its transmission spectrum using a tunable laser associated with a data acquisition system (Yenista Tunics and CT400) (Fig. 2). We use a polarization rotator to inject TE-polarized light into the grating. The pump-rejection filter has a 3 dB bandwidth of 5.5 nm. In our case, the usable bandwidth is only 3 nm, as only the deepest part of the filter can be exploited for the rejection of the pump. As shown in Fig. 2, the measured rejection of the filter is higher than 60 dB (dark-blue curve), which corresponds to the noise floor (red dashed line) of our detector. This measured rejection rate is consistent with state-of-the-art realizations for single-chip PF16,17,18. To further investigate the performances of the PF, we need to qualify the entangled states generated on an advanced integrated circuit including this PF.

Time correlation measurements

We proceed to time correlation measurements as a prerequisite to two-photon interference for qualifying the amount of entanglement carried by the photon pairs generated and filtered on chip. To reveal time correlation (Fig. 1c), signal and idler photons are separated and sent to different detectors that are connected to a time-to-digital converter (TDC). The statistics in the arrival times and related delays is then recorded and reconstructed as a coincidence histogram (Fig. 3a). To this end, the paired photons are demultiplexed at the chip’s output with off-the-shelf filters of only 22 dB cross-talk (as shown in Fig. 1e). The pump is set to λp = 1534.2 nm (C-band) with an input power of 2.8 mW after the polarization controller (Fig. 1a). As a first step, we study the closest resonances from the pump, i.e., paired channels distant by two- and three-FSR, as they may suffer preferably from the pump photonic noise. The related wavelength for the two- and three-FSR shift are highlighted in Fig. 2 and detailed in the Methods. Examples of typical coincidence histograms are shown in Fig. 3a, where distinct coincidence peaks emerge over a small background of accidental counts. This stands as a clear signature of the simultaneous emission of the photon pairs. The width of the coincidence peak is given by the convolution of the coherence time of the photons σcoherence ~ 110 ps, of the detectors’ timing jitters σjitter ~ 100 ps, and of the time resolution of the TDC σresolution ~ 1 ps. The full width at half maximum of the coincidence peak is about 160 ps, which is consistent with \(\sqrt{{\sigma }_{\mathrm {coherence}}^{2}+{\sigma }_{\mathrm {jitter}}^{2}+{\sigma }_{\mathrm {resolution}}^{2}} \sim 150\ {\rm{ps}}\). Both the two-FSR shift and three-FSR shift resonances exhibit similar results.

a The histograms represent the recorded coincidences for both two-FSR shift and three-FSR shift resonances. The overall integration time is 10 s and the measurements are done with SSPD detectors (Fig. 1b). The two-FSR rate is of about 116 counts/s with an SNR of 67.5, whereas the three-FSR coincidence rate is of about 151 counts/s with a SNR of 100. The noise level within the peak is between 1.5 counts/s and 1.7 counts/s. b The histograms represent the coincidences at the output of the interferometric setup sketched in Fig. 1c for the two-FSR shift resonances. They show a maximum and a minimum of interference (region (1)). Here, the overall integration time is of 5 s. The error bars for all points come from Poissonian statistics associated with the pairs (e.g., \(\sqrt{N}\), N being the number of coincidences). It is noteworthy that similar histogram are obtained for the three-FSR shift case.

We now consider the internal brightness of the ring (Table 1). The overall losses of the setup, including the input/output and propagation losses of the chip, are outlined in Table 2 of the Methods section. The single count rates in the coincidence experiment are of 4 × 104 signal counts per seconds and 3 × 104 idler counts per seconds, with 17 dB and 18.5 dB of losses, respectively. The overall coincidence peak spreads over several time bins and shows an average of 120 coincidences per second over a time window of 400 ps (Fig. 3a). With all those figures, we can infer an internal generated photon-pair rate of (2.1 ± 0.2) × 106 pairs/s. As the ring shows resonances of 42 pm width (Fig. 2b) and the power in the ring is estimated to be 0.9 mW, we estimate an internal brightness of ~500 pairs/s/mW2/MHz. Due to the non-deterministic wavelength separation induced by the beam splitter (Fig. 1a) and the spectral filtering ensured by the bandpass filters in each arm, the rate at the output of the chip is 4 times higher, i.e., about 480 pairs generated per second for each channel pair. Let us stress that this coincidence rate stands among the best values reported for photonic devices embedding several key components7,20,34,35,36,37,38. In comparison, similar realizations suffer from low coincidence rates due to prohibitive losses, precluding any further analysis of entanglement19,20. It is noteworthy that the other interesting feature reported in Table 2 is the 2 dB loss for the PF, which is almost only due to propagation. This low value associated with a high-rejection level and a narrow bandwidth makes our pump-filtering strategy a promising candidate for next-generation quantum photonic circuits.

Before addressing entanglement analysis, a relevant figure of merit associated with time correlation measurements consists in evaluating the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) between the coincidence peak and the background noise. In the measurements presented in Fig. 3a, the SNR is >60 for both histograms (2-FSR shift and 3-FSR shift). Accidental counts mainly come from successive pair events, when one of the two photons has lost its paired companion. This SNR can be improved by using a lower pump power at the price of reduced coincidence counts and of longer integration times39. There, our strategy is slightly different and promotes pragmatic realizations of QIS experiments by emphasizing high-coincidence counts, while keeping a moderate but safe SNR9.

Energy-time entanglement analysis

The photon pairs are genuinely energy-time entangled, as they are produced by SFWM15,40,41,42,43,44,45,46. Entanglement is analyzed using a folded-Franson arrangement consisting of an unbalanced fiber Michelson interferometer (F-MI) (Fig. 1d)23,47. A piezo-transducer is used to extend the fiber in one arm, changing the imbalance of the interferometer, and thus the relative phase between the two arms. Energy-time quantum correlation are revealed by the coherent superposition of the contributions coming from identical two-photon paths (short–short and long–long) contrarily to the contributions coming from different paths (long–short, or conversely). Consequently, a coincidence histogram with the emergence of three peaks is recorded9 (Fig. 3b). The central peak gathers the two indistinguishable contributions leading to interference, provided all experimental conditions reported in the Methods section are satisfied. The total and average numbers of coincidences in the central and side peaks, respectively (Fig. 3b) are used to plot the patterns shown in Fig. 4.

Each point is obtained with a 5 s integration time and the step increment of π/8. The side peak rates show the stability of the measurement. Here, noise counts are not removed from the measurements, (a) corresponds to the two-FSR shift resonances with a noise of 0.5 counts/s, (b) is the three-FSR shift resonances with a noise of 0.9 counts/s. The error bars for all points come from Poissonian statistics.

Interference patterns recorded for two-FSR shift (Fig. 4a) and three-FSR shift (Fig. 4b) resonances are obtained with a phase resolution of \(\frac{2\pi }{20}\), compliant with the F-MI stability. The interferometer π-dephasing timescale is in the hour range, which leaves enough time to perform a scan without being subjected to detrimental phase drifts. The side peak in Fig. 3b also shows the stability of the photon generation process. The typical acquisition time for recording two fringes is 6 min. The noise figure in the central peak is of about 0.5 and 0.9 counts/s for the two-FSR shift and three-FSR shift resonances, respectively. The two-photon interference fringes are fitted with respect to N0(1 − V cos(2ϕ)), where N0 is the mean number of coincidences and V the fringes visibility considered as a free-fit parameter to infer the visibility. Raw visibilities of (98.0 ± 2)% and (96.7 ± 3)% without subtraction of photonic or detector noise are obtained, for the two-FSR shift pairs (R2 of 0.96) and for the three-FSR shift pairs (R2 of 0.99), respectively. The net visibility is obtained by subtracting photonic noise originating from the detectors’ dark counts (200 counts/s) and corresponds to (99.6 ± 1.5)% and (98.0 ± 1.2)% for the two-FSR shift and three-FSR shift pairs, respectively.

We extend our investigations according the same methodology for subsequent paired channels within the S-band and the full C-band30. More precisely, we explore the entanglement quality of 9 extra paired channels, i.e., up to 11-FSR shift, spaced by 40 nm (1515–1555 nm) on both sides of the pump channel, leading to the ability of supporting a high number of users in a multiplexing scenario (Table 2)9. The details for the signal and idler wavelengths corresponding to i-FSR shift, with 2 ≤ i ≤ 11, are reported in the Methods. The raw visibilities for all the paired channels exceeds 92% for an internal rate ≥1 MHz as shown in Fig. 5.

It is noteworthy that two other photonic noise contributions have been evaluated before being neglected: multiple photon-pair events and non-perfect overlap between the two identical two-photon paths (“short–short” and “long–long”). The former was not considered because of the low mean number of photon pairs per gate window (\(\bar{n}=3\,\times\,1{0}^{-4}\)). The origin of the latter contribution lies in the wavelength difference between the signal and the idler over the full range of analysis (~50 nm), leading to potentially slightly distinguishable “short–short” and “long–long” two-photon paths. The time arrival difference has been evaluated to be <10−5 ps, whereas the full width at half maximum of the coincidence peak is equal to 160 ps (Fig. 3a), which represents several orders magnitudes higher than the shift between the “short–short” and “long–long” path.

This result not only stands as among the highest raw quantum interference visibility for time-energy entangled photons from a micro/nanoscale integrated circuit over such a large spectral window (partially over the S-band and fully over the C-band) but also the first entanglement qualification of a complex integrated circuit including the PF7,36,48. Furthermore, generating genuinely a pure maximally entangled state from an integrated source associated with high-coincidence rates will be of special interest for QIS experiments.

Discussion

Our strategy is geared towards developping “Plug-&-Play” and scalable quantum photonic systems by exploiting sophisticated silicon-based architectures combined with off-the-shelves telecom components16,17,18,19,20. Notably, the high SNR (>60) and the low noise observed in both coincidence and interference experiments (Figs. 3 and 4) show the effectiveness of our pump-rejection solution, achieved in an all-passive manner. Furthermore, the acquisition time for recording the interference patterns is on the order of several minutes, allowing a setup free of complex stabilization systems for the F-MI. It is noteworthy that the on-chip pump rejection is complemented by two bandpass filters, corresponding to a total amount of 82 dB, which is lower than the typical necessary value of 100 dB19. This difference probably arises from an underestimation of the real rejection of the on-chip PF, which is closer to 80 dB. This assumption is confirmed by a previous work based on the design, the implementation, and the qualification of such a filter28. Moreover, signal and idler photons are coupled to off-chip bandpass filters leading to spatial filtering of the light scattered from the chip.

We also stress that the modal coupler cascaded with the PF allows the exploitation of the rejected signal, to match the frequency combs from the RR with the pump laser (Fig. 1a). We could use this strategy to demultiplex signal and idler photons in an all-passive way by cascading several modal couplers of this type. In this case, the period of the gratings that are part of the PF has to be adjusted according to the signal and the idler wavelengths. Furthermore, the slope of the edges corresponding to the transition from high blocking to high transmission of the PF (Fig. 2) is evaluated to be of 22.3 dB/100 pm, therefore being compatible with narrower spectral channels. Hence, the exploitation of a micro-ring associated with a 50 GHz FSR instead of 200 GHz stands as a relevant improvement to enhance the number of users supported by the chip up to 44 pairwise users49. This solution would neither impact the design of the PF nor the demultiplexing stages, as 50 GHz stands as a standard for the ITU (International Telecommunication Union) channel grid.

In summary, we have demonstrated a near-perfect entanglement quality out of a single photonic chip embedding both generation and pump-rejection building blocks. We have measured raw visibilities exceeding 92% for 11 channel pairs over telecom bands covering the spectral range 1515–1555 nm. Our approach, combining high performance, flexibility, scalability, and compliance with telecom standards, stands promising for operational QIS applications. This brings an essential step closer to demonstrate ambitious photonic quantum devices enabling on-chip generation, filtering, and manipulation of quantum states.

Methods

Design

The RR is in a racetrack configuration with a radius of 49 μm and a straight section of 18 μm. The gap between the ring and the bus waveguide is 150 nm wide. The ring waveguide width is 600 nm, making it multi-mode, whereas the bus waveguide width is 400 nm, to be a single mode.

The PF is composed of nine cascaded sections of multi-mode BFs, each being 300 μm long. The corrugation of the filters is Wcorr = 225 nm, the waveguide width and the pitch of each section are equal to W = 1.15 μm, and P = 290 nm, respectively, with a duty cycle of 50%. Tapers and apodizing of the corrugation have been placed at the ends of all sections to improve transmission. Consequently, the losses of our filter comes mainly due to the propagation and are as low as 2.5 dB. Furthermore, our device works fully passively. Finally, the grating couplers are optimized to reduce Fabry–Perot ripples in the collected signal for an easier analysis of the transmission spectrum.

Fabrication

The circuit was made using silicon-on-insulator wafers comprising a 220 nm-thick silicon and a 3 μm buried oxide layer. Electron beam lithography (Nanobeam NB-4 system 80 kV, with a step size of 5 nm), dry, and inductively coupled plasma etching (SF6 gas) were used to define the patterns. It is noteworthy that all fabrication steps, notably concerning the dimensions of the components (minimum feature size of 145 nm from the pitch), can be realized with standard deep-UV lithography.

Measurements

The full experimental setup is presented in Fig. 1. Light from a narrowband tunable telecom CW laser (Yenista Tunics Plus laser) is coupled to the device. Before the silicon chip, a tunable bandpass filter (Yenista XTM-50) is used to clean the laser from the ASE, which would otherwide be coupled to the chip and not filtered by any other components. Then a polarization controller is used to set the laser light to the TE polarization mode (Fig. 1a). The TM polarization is suppressed by both grating couplers (about 40 dB each) of the circuit and by the waveguide itself due to the asymmetric cladding (silicon waveguide between silica and air layers). Finally, a Peltier driven by a temperature controller (Thorlabs TED 200C) is used to ensure a thermal regulation of the sample to (21 ± 0.01) °C.

For the time correlation measurements, we employ, after the sample, a beam splitter followed in each arm by a bandpass tunable filter (OZ optics) of 600 pm bandwidth and 20 dB extinction ratio (Fig. 1a). This is for demultiplexing signal and idler photons, one filter being set to the signal wavelength and the other to the idler wavelength (Fig. 1e). We use two superconducting single photon detectors (SSPD, ID Quantique ID281) connected to a TDC (PicoQuant HydraHarp 400) for recording coincidence counts with a bin precision of 1 ps.

Exploiting energy-time observable relies on the systematic lack of information of the pairs’ creation times within the coherence time of the employed CW pump laser. In practice, the twin photons pass through the unbalanced interferometer (see Fig. 1d) following either the same path (short–short or long–long) or different paths (long–short, or conversely)9. These contributions are distinguished by measuring the arrival times of the idler photons with respect to those of the signal photons using the TDC. This enables recording a coincidence histogram comprising three peaks (Fig. 3b). The side peaks (labeled (2) and (3)) correspond to the situations where the paths are different, whereas the central peak (labeled (1)) gathers the two indistinguishable cases (short–short and long–long) leading to two-photon interference. It is noteworthy that the F-MI imbalance (~ 350 ps) needs to be greater than the coherence time of the single photons (~100 ps) to avoid first-order interference and shorter than the coherence time of the CW pump laser (~100 ns), to have a coherent superposition between short–short and long–long contributions in the central peak. By using a narrow coincidence window that excludes the side peaks, entanglement can be revealed according to the coincidence counting evolution N0(1 − V cos(2ϕ)), where V and ϕ represent the fringe visibility and the phase accumulated by the single photons in the interferometer, respectively. The visibility stands as our the main figure of merit and correlation described by such a coincidence function with a visibility higher than 70.7% cannot be described by any local hidden-variables theories50.

References

Bennett, C. H. & DiVincenzo, D. P. Quantum information and computation. Nature 404, 247–255 (2000).

Acín, A. et al. The quantum technologies roadmap: a European community view. New J. Phys. 20, 080201 (2018).

Knill, E., Laflamme, R. & G, M. A scheme for efficient quantum computation with linear optics. Nature 409, 46–52 (2001).

Diamanti, E., Lo, H.-K., Qi, B. & Yuan, Z. Practical challenges in quantum key distribution. npj Quant. Inf. 2, 16025 (2016).

Qiang, X. et al. Large-scale silicon quantum photonics implementing arbitrary two-qubit processing. Nat. Photonics 12, 534–539 (2018).

Samara, F. et al. High-rate photon pairs and sequential time-bin entanglement with Si3N4 ring microresonators. Opt. Express 27, 19309–19318 (2019).

Grassani, D. et al. Micrometer-scale integrated silicon source of time-energy entangled photons. Optica 2, 88–94 (2015).

Chen, Y. et al. Wavelength-tunable entangled photons from silicon-integrated iii-v quantum dots. Nat. Commun. 7, 10387 (2016).

Aktas, D. et al. Entanglement distribution over 150 km in wavelength division multiplexed channels for quantum cryptography. Laser Photonics Rev. 10, 451–457 (2016).

Orieux, A., Versteegh, M. A. M., Jöns, K. D. & Ducci, S. Semiconductor devices for entangled photon pair generation: a review. Rep. Prog. Phys. 80, 076001 (2017).

Wang, J. et al. Multidimensional quantum entanglement with large-scale integrated optics. Science 360, 285–291 (2018).

Jin, H. et al. On-chip generation and manipulation of entangled photons based on reconfigurable lithium-niobate waveguide circuits. Phys. Rev. Lett. 113, 103601 (2014).

Vergyris, P. et al. On-chip generation of heralded photon-number states. Sci. Rep. 6, 35975 (2016).

Faruque, I. I., Sinclair, G. F., Bonneau, D., Rarity, J. G. & Thompson, M. G. On-chip quantum interference with heralded photons from two independent micro-ring resonator sources in silicon photonics. Opt. Express 26, 20379–20395 (2018).

Silverstone, J. W. et al. Qubit entanglement between ring-resonator photon-pair sources on a silicon chip. Nat. Commun. 6, 7948 (2015).

Popović, M. A. et al. Multistage high-order microring-resonator add-drop filters. Opt. Lett. 31, 2571 (2006).

Luo, X. et al. Silicon high-order coupled-microring-based electro-optical switches for on-chip optical interconnects. IEEE Photon. Technol. Lett. 24, 821–823 (2012).

Dong, P. et al. GHz-bandwidth optical filters based on high-order silicon ring resonators. Opt. Express 18, 23784 (2010).

Piekarek, M. et al. High-extinction ratio integrated photonic filters for silicon quantum photonics. Opt. Lett. 42, 815 (2017).

Harris, N. C. et al. Integrated source of spectrally filtered correlated photons for large-scale quantum photonic systems. Phys. Rev. X 4, 041047 (2014).

Ong, J. R., Kumar, R. & Mookherjea, S. Ultra-high-contrast and tunable-bandwidth filter using cascaded high-order silicon microring filters. IEEE Photon. Technol. Lett. 25, 1543–1546 (2013).

Elshaari, A. W. et al. On-chip single photon filtering and multiplexing in hybrid quantum photonic circuits. Nat. Commun. 8, 379 (2017).

Franson, J. D. Bell inequality for position and time. Phys. Rev. Lett. 62, 2205 (1989).

Ekert, A. K. Quantum cryptography based on bell’s theorem. Phys. Rev. Lett. 67, 661–663 (1991).

Mattle, K., Weinfurter, H., Kwiat, P. G. & Zeilinger, A. Dense coding in experimental quantum communication. Phys. Rev. Lett. 76, 4656–4659 (1996).

de Riedmatten, H. et al. Long distance quantum teleportation in a quantum relay configuration. Phys. Rev. Lett. 92, 047904 (2004).

Kaiser, F. et al. Quantum enhancement of accuracy and precision in optical interferometry. Light Sci. Appl. 7, 17163 (2018).

Oser, D. et al. Coherency-broken bragg filters: surpassing on-chip rejection limitations. Laser Photon. Rev 13, 1800226 (2018).

Franson, J. D. Bell inequality for position and time. Phys. Rev. Lett. 62, 2205–2208 (1989).

Iannone, E. Telecommunication Networks (CRC Press, 2011).

Matsuda, N. et al. On-chip generation and demultiplexing of quantum correlated photons using a silicon-silica monolithic photonic integration platform. Opt. Express 22, 22831–22840 (2014).

Wang, J. et al. Broadband and fabrication-tolerant on-chip scalable mode-division multiplexing based on mode-evolution counter-tapered couplers. Opt. Lett. 40, 1956–1959 (2015).

Benedikovic, D. et al. Subwavelength index engineered surface grating coupler with sub-decibel efficiency for 220-nm silicon-on-insulator waveguides. Opt. Express 23, 22628–22635 (2015).

Azzini, S. et al. Ultra-low power generation of twin photons in a compact silicon ring resonator. Opt. Express 20, 23100–23107 (2012).

Jiang, W. C., Lu, X., Zhang, J., Painter, O. & Lin, Q. Silicon-chip source of bright photon pairs. Opt. Express 23, 20884 (2015).

Wakabayashi, R. et al. Time-bin entangled photon pair generation from si micro-ring resonator. Opt. Express 23, 1103–1113 (2015).

Suo, J., Dong, S., Zhang, W., Huang, Y. & Peng, J. Generation of hyper-entanglement on polarization and energy-time based on a silicon micro-ring cavity. Opt. Express 23, 3985 (2015).

Santagati, R. et al. Silicon photonic processor of two-qubit entangling quantum logic. J. Opt. 19, 114006 (2017).

Rogers, S., Lu, X., Jiang, W. C. & Lin, Q. Twin photon pairs in a high-q silicon microresonator. Appl. Phys. Lett. 107, 041102 (2015).

Azzini, S. et al. From classical four-wave mixing to parametric fluorescence in silicon microring resonators. Opt. Lett. 37, 3807–3809 (2012).

Jiang, W. C., Lu, X., Zhang, J., Painter, O. & Lin, Q. Silicon-chip source of bright photon pairs. Opt. Express 23, 20884–20904 (2015).

Grassani, D. et al. Energy correlations of photon pairs generated by a silicon microring resonator probed by stimulated four wave mixing. Sci. Rep. 6, 23564 (2016).

Wakabayashi, R. et al. Time-bin entangled photon pair generation from si micro-ring resonator. Opt. Express 23, 1103–1113 (2015).

Preble, S. F. et al. On-chip quantum interference from a single silicon ring-resonator source. Phys. Rev. Appl. 4, 021001 (2015).

Silverstone, J. W. et al. On-chip quantum interference between silicon photon-pair sources. Nat. Photonics 8, 104 (2013).

Faruque, I. I., Sinclair, G. F., Bonneau, D., Rarity, J. G. & Thompson, M. G. On-chip quantum interference with heralded photons from two independent micro-ring resonator sources in silicon photonics. Opt. Express 26, 20379–20395 (2018).

Thew, R. T., Tanzilli, S., Tittel, W., Zbinden, H. & Gisin, N. Experimental investigation of the robustness of partially entangled qubits over 11 km. Phys. Rev. A 66, 062304 (2002).

Rogers, S., Mulkey, D., Lu, X., Jiang, W. C. & Lin, Q. High visibility time-energy entangled photons from a silicon nanophotonic chip. ACS Photonics 3, 1754–1761 (2016).

Imany, P. et al. 50-GHz-spaced comb of high-dimensional frequency-bin entangled photons from an on-chip silicon nitride microresonator. Opt. Express 26, 1825 (2018).

Tanzilli, S. et al. Ppln waveguide for quantum communication. Eur. Phys. J. D. Atom. Mol. Opt. Plasma Phys. 18, 155–160 (2002).

Acknowledgements

We thank Bhaskar Kanseriin for fruitful discussion and valuable inputs, especially for the last measurements. This work has been conducted within the framework of the project OPTIMAL granted by the European Union by means of the Fond Européen de développement regional (FEDER). We also acknowledge financial support from the Agence Nationale de la Recherche (ANR) through the projects SITQOM (grant agreement ANR-15-CE24-0005) and the French government through its program “Investments for the Future” under the Université Côte d’Azur UCA-JEDI project (under the label Quantum@UCA and OPENING) managed by the ANR (grant agreement ANR-15-IDEX-01). The sample fabrication has been performed at the Plateforme de Micro-Nano-Technologie/C2N, which is partially funded by the “Conseil Général de l’Essonne.” This work was partly supported by the French RENATECH network. We also acknowledge technical support from IDQ.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

F.M. and D.O. performed the experiments. C.A.R. and D.O. designed the circuit. X.L. and D.O. fabricated the sample. S.T. and L.L. designed the experiment. G.S., X.H., and O.A. performed calibrations and technical support for the detectors. S.T., L.L., and D.O. wrote the paper with inputs from L.V. and E.C.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Oser, D., Tanzilli, S., Mazeas, F. et al. High-quality photonic entanglement out of a stand-alone silicon chip. npj Quantum Inf 6, 31 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41534-020-0263-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41534-020-0263-7

This article is cited by

-

Satellite-based quantum information networks: use cases, architecture, and roadmap

Communications Physics (2023)

-

Ultra-efficient generation of time-energy entangled photon pairs in an InGaP photonic crystal cavity

Communications Physics (2023)

-

648 Hilbert-space dimensionality in a biphoton frequency comb: entanglement of formation and Schmidt mode decomposition

npj Quantum Information (2021)

-

Microstructure and domain engineering of lithium niobate crystal films for integrated photonic applications

Light: Science & Applications (2020)