Abstract

Study design

Descriptive study.

Objectives

The aim of this manuscript is to describe the development process of the data set for the National Spinal Cord Injury Registry of Iran (NSCIR-IR).

Setting

SCI community in Iran.

Methods

The NSCIR-IR data set was developed in 8 months, from March 2015 to October 2015. An expert panel of 14 members was formed. After a review of data sets of similar registries in developed countries, the selection and modification of the basic framework were performed over 16 meetings, based on the objectives and feasibility of the registry.

Results

The final version of the data set was composed of 376 data elements including sociodemographic, hospital admission, injury incidence, prehospital procedures, emergency department visit, medical history, vertebral injury, spinal cord injury details, interventions, complications, and discharge data. It also includes 163 components of the International Standards for the Neurologic Classification of Spinal Cord Injury (ISNCSCI) and 65 data elements related to quality of life, pressure ulcers, pain, and spasticity.

Conclusion

The NSCIR-IR data set was developed in order to meet the quality improvement objectives of the registry. The process was centered around choosing the data elements assessing care provided to individuals in the acute and chronic phases of SCI in hospital settings. The International Spinal Cord Injury Data Set was selected as a basic framework, helped by comparison with data from other countries. Expert panel modifications facilitated the implementation of the registry process with the current clinical workflow in hospitals.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Different incidences of traumatic spine fractures (TSF) with or without spinal cord injury (SCI) have been reported in different geographic regions [1,2,3,4,5]. The incidence of traumatic SCI (TSCI) varies between 3.6 and 195.4 per one million around the world; in developing countries, an incidence of 25.5 SCI per million has been reported [6, 7]. In Iran, Heidari et al. reported TSF in 3.8% (619 out of 16,321) of trauma admissions between 1999 and 2004 using the National Trauma Registry (NTR) data [8]; 5.8% (36 out of 619) of people with TSF admitted to a hospital had an associated SCI. In another study, the incidence of TSF in Tehran was estimated to be about 16.35 per 100,000 and less than half of these patients had a simultaneous SCI [9]. The incidence of TSCI in Iran was estimated as 9 per 100,000 persons by another study [10].

When the spinal cord is damaged, long-term disability often ensues [10]. TSCI is a condition with multiple comorbidities and considerable health, social, and economic impacts. The burden of these impacts can be managed by improving quality of care. The lack of a reliable source of information about spine trauma with or without SCI is a significant barrier in evaluation and planning of systems of prevention, control, and care [11]. Until now, there was no spine-specific trauma database or registry system in Iran. The National SCI Registry of Iran (NSCIR-IR) is a project supported by the Ministry of Health and Medical Education to collect and provide TSF and SCI data to evaluate and improve the quality of care of persons with SCI [12].

The development of a data set is an essential phase of designing a registry system [13]. According to Kowal et al., a data set is a common set of data elements used to collect and report data in the registry [14]. Many studies have emphasized the importance of a data set to create national databases and support information sharing on diseases, injuries, and other health-related problems [14,15,16]. One of the most important and effective tasks for the success or failure of a registry system is the selection of appropriate data items [17]. Data set development is a critical step for nonepidemiologic registries on traumatic conditions that can lead to long-term disabilities such as TSF/SCI. The objectives for a SCI registry are focused on care and outcome measurements, requiring various data inputs from different independent and distinct resources. This study focuses on the development process of the data set for the NSCIR-IR and delineates our experiences, which might be useful for future registries, specifically in developing countries with limited budgets, resources, and information technology infrastructures.

Methods

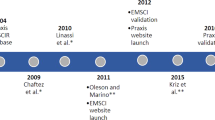

The development of NSCIR-IR has been one of the main priorities of the National Iranian SCI Research Network since 2012. The data set of NSCIR-IR was developed between March and October 2015. An expert panel with three neurosurgeons, one physiatrist, one general practitioner, one nurse, one community medicine physician, one emergency physician, two epidemiologists, and one health information management specialist was formed. We followed a stepwise approach in the development of the data set. The steps included (i) review of the data sets in similar SCI registries, (ii) selection of a data set as the base framework of the NSCIR-IR data set by the expert panel, and (iii) modification of the basic framework according to data needs, registry objectives, and feasibility of data collection.

First, a simple review was performed on the data sets of three SCI registries of Australia (Australian Spinal Cord Register), Canada (Rick Hansen SCI Registry (RHSCIR)), and Europe (European Multicenter Study about SCI).

Later, the RHSCIR data set was selected as our basic framework to develop an initial draft data set. The selections were made based on the similarity of RHSCIR to our registry in registry type (Spinal column and SCI (TSF/SCI)) inclusion criteria. Sixteen sessions of the expert panel were held between March and October 2015. We translated the RHSCIR data set dictionary into Farsi and then our expert panel independently reviewed the translation. The accessibility of the data elements of the RHSCIR was examined by experts who were aware of the clinical documentation status and the general content of medical records in hospitals of Iran. It was noted that several variables are not recorded in patients’ hospital charts; therefore, patient medical records were considered as the secondary data source of the registry. Comparability of our registry data with other countries was another issue that was discussed by the expert panel. International data standards are recommended by the World Health Organization (WHO), therefore, the International SCI Data Sets (ISCIDS) were also reviewed. At the third step, the expert panel made changes to Iranian data set of NSCIR-IR in order to accommodate our major data elements and concerns of quality of care. For example, our data set registers different time points from injury time to the time of arrival of ambulance to the trauma scene, time of arrival to hospital, or to a referral center, and time of the surgical stabilization with or without spinal cord decompression. With this design, it will be possible to identify major time delay points in our care providing system.

Results

Table 1 compares the RHSCIR data set with the two other registries [18, 19]. The RHSCIR data set includes more than 307 variables that cover quality of care [18, 20]. The RHSCIR data set has two types of minimal and extended data elements in which the minimal data set includes 200 mandatory data elements that must be recorded for all patients including those who do not consent to be part of the registry. These minimal data set includes name, family name, age, time, place and mechanism of injury, and questions which are essential for patients’ treatment by care providers. The extended data elements (107 elements) are recorded only for patients who consent to be part of the registry [21]. Our expert panel reviewed the RHSCIR data elements. Some of the RHSCIR data elements were not accessible through primary data sources of the registry e.g., patient-reported or clinician-reported data, observation and measurement by the registry members. Medical records were considered as the secondary data source of the registry, however, several variables in the RHSCIR data set were also not recorded in the patient medical records. Table 2 shows the data items and variables, which we did not include in our registry (Table 2).

According to the review of WHO and ISCIDS [22,23,24], our strategic committee had considerations regarding comparability of the designed data set with international data. WHO recommends the use of standardized coding systems such as the international classification of diseases (ICD), International Standards for Neurological Classification of SCI and ISCIDS for data collection to facilitate comparison between different patients, centers, and countries [22]. The RHSCIR data set and other data sets (Appendix 1) were different from the ISCIDS. Therefore, the expert panel decided was not convinced to use the RHSCIR data set due to concerns of accessibility and comparability of data in our registry with the RHSCIR data set. The expert panel concluded to use ISCIDS as the basic framework of NSCIR-IR data set. ISCIDS includes a core data set and several specialized data sets. The core data set includes 24 variables that are the minimal data required for collection for all people with SCI in acute inpatient settings [25]. There are 12 more data sets which are focused on different aspects of SCI and SCI consequences [24]. According to the registry objectives and registration process, the expert panel selected 174 data items from ISCIDS. Data selections were based on accessibility of data and usefulness in quality of care assessment in the acute settings. Selected data items were organized into five sections based on the logical sequence in the process of care (Table 3).

After translation of data items into Farsi, case report forms were designed. Panel members evaluated designed forms and applied the required methods. Major and minor modifications were made to overcome the mentioned challenges in Box 1 (Table 4).

The final version of the NSCIR-IR data set was developed with 350 data elements. It includes one data set for acute and one data set for chronic phase of injury (rehospitalization data). Our data items are two of types: mandatory and conditional. Conditional data items are data items that are considered as mandatory based on the clinical situation of the patient. If a data item is not applicable for a patient, it is not necessary to be completed for that patient. For example, if the accident was not a traffic accident, then it is not necessary to record the accident data. Table 5 shows the components of the final version of NSCIR-IR data set. The items were organized into seven case report forms for acute phase and four case report forms for the chronic phase. All were used in the pilot phase of registry implementation (Table 5). After 8 months of implementation of the pilot phase in three trauma hospitals, changes were made to the data set that are (i) details on the types of respiratory, cardiovascular, and other comorbidities were added into admission form, (ii) procedures in the first hospital in cases with inter-hospital patient transfer were added into admission form, (iii) injury type of Atlas and Axis cervical vertebra (C1-C2), were separated from the other vertebrae and were added as a question into the injury form, (iv) one item was added into the intervention form for the vertebra or vertebrae on which surgery was performed, and (v) one item was added into the discharge form for the type of external fixation device, which patient uses at the time of hospital discharge.

Discussion

Our study presents an overview of the data set development process for the NSCIR-IR. Our evidence-based approach along with interdisciplinary expert panel review helped us to develop a comprehensive, yet applicable, data set. Some groups have used review of current evidence and formation of working groups to select the registry data elements [26, 27]. Others have conducted either a survey or Delphi method on an initial version of the data set [28,29,30]. Svensson-Ranallo et al. [31] performed a comprehensive review for methodologies of data set development in health care. The results of this review showed that there are different methods such as survey, systematic review, chart review, and Delphi technique. The most common methods are the use of experts and stakeholders, but the authors suggested a combined approach with literature review, chart review, expert committee, and organized data for developing the minimum data set [31]. In our study, we used the literature review and expert committee to form the data sets.

It is important to choose the right data elements for a registry. Tee et al. stated that correct data selection items of a registry lead to a balance between comprehensiveness and practicality of the registry [32]. Although, at first, we wanted to have a comprehensive and detailed data set, which meets all present and future data requirements for research and care evaluation, the unavailability of most data items and the necessity of an international framework for comparability of our registry led us toward using the ISCIDS.

Compliance evaluation of determined data elements with routine clinical practice was effective to reduce registration workload. Imposition of required uncommon practice in current clinical practice increases the cost. Tee et al. emphasized the number of data elements collected that should be practical based on routine process [32]. For example, when we chose the RHSCIR data set as our framework, we found that some of the data were not accessible at all through primary data sources of the registry. For example, we found the hesitancy of our patients in providing data related to their income, work status, drinking, and some other measures as a big barrier for data collection. In other words, assessing income is very difficult in Iran especially in people who are self-employed. Most self-employed Iranians do not express their real income for cultural reasons. Usually, government employees have specific income data.

In addition, assessments and interventions for patients in clinical practice differ between Iran and Canada. For instance, height and weight of patients are not taken on arrival to the hospital. Also, some clinical assessments such as mobility or pain assessment with specialized tools (e.g., Berg Balance Scale, Leeds Assessment of Neuropathic Symptoms and Signs, Douleur Neuropathique 4) are not part of the routine assessments in Iran. Also, rehabilitation and assistive devices are not provided in a specialized manner to the patients in the acute phase. Instead, rehabilitation and support services are available at the level of long-term care. Although, there is connection between the acute care system and long-term care system; there is a lack of communication and information sharing between care providers working in the two levels of Iran health care system. Patients normally work as messengers, carrying information between the two levels. In contrast, Canada has a robust information technology infrastructure. There are multiple database and reporting systems at all of the health care services levels. These include the Hospital Morbidity Database and Discharge Abstract Database for ambulatory and hospital care, National Rehabilitation Reporting System for rehabilitation care, NTR for trauma care, Continuing Care Reporting System, and Home Care Reporting System for continuing and long-term care [33,34,35,36,37,38]. Using primary data sources is not practical in Iran due to limited human resources for registration and funds allocated according to the large scale of data that led to a time-consuming and tedious registration process. Therefore, it was predicted that using the Canadian SCI registry as the backbone of data set in NSCIR-IR is impractical.

The NSCIR-IR data set contains spine trauma data such as the injury morphology and injury type according to the AOSPINE injury classification system. The classification is used only in the RHSCIR and not used by other TSF/SCI registries. Therefore, it is a strong point of the NSCIR-IR data set. In relation to patient outcome, the data set includes the Glasgow Outcome Scale that is a physician-reported outcome; however, it does not include any patient-reported outcome data, specifically about patient functional independence. Other SCI registries use standard measures for patient-reported outcome such as the Short Form 12 or 36 Health Survey, the Spinal Cord Independence Measure, or the Functional Independence Measure [21, 39, 40]. This is a weak point of the NSCIR-IR data set.

Using the ISCIDS as the basic framework of the NSCIR-IR data set facilitates international comparisons on the quality of provided care to TSF/SCI patients. One of the limitations of our study was that we chose variables based on the expert’s opinion on the availability of data in current medical records. However, due to lack of electronic health records and national or regional standards in medical records documentations, expert opinion was the best resource that we could rely on.

In summary, the NSCIR-IR data set was developed to meet the quality objectives of the registry. It focuses on data representing quality of care provided to patients with TSCI in the acute and chronic phases of their injury. The selected basic framework of the data set for the ISCIDS can help to compare national data with data from other countries. Expert panel modifications facilitate the integration of the registration process with the current clinical workflow within the hospitals.

Data availability

Anonymous data of NSCIR-IR may be accessible for research use, upon written request and approval from the steering committee.

References

Singh A, Tetreault L, Kalsi-Ryan S, Nouri A, Fehlings MG. Global prevalence and incidence of traumatic spinal cord injury. Clin Epidemiol. 2014;6:309–31.

Hagen EM, Eide GE, Rekand T, Gilhus NE, Gronning M. A 50-year follow-up of the incidence of traumatic spinal cord injuries in Western Norway. Spinal Cord 2010;48:313–8.

Lenehan B, Street J, Kwon BK, Noonan V, Zhang H, Fisher CG, et al. The epidemiology of traumatic spinal cord injury in British Columbia, Canada. Spine 2012;37:321–9.

Divanoglou A, Levi R. Incidence of traumatic spinal cord injury in Thessaloniki, Greece and Stockholm, Sweden: a prospective population-based study. Spinal Cord 2009;47:796–801.

Perez K, Novoa AM, Santamarina-Rubio E, Narvaez Y, Arrufat V, Borrell C, et al. Incidence trends of traumatic spinal cord injury and traumatic brain injury in Spain, 2000-2009. Accid; Anal Prev. 2012;46:37–44.

Rahimi-Movaghar V, Sayyah MK, Akbari H, Khorramirouz R, Rasouli MR, Moradi-Lakeh M, et al. Epidemiology of traumatic spinal cord injury in developing countries: a systematic review. Neuroepidemiology 2013;41:65–85.

Jazayeri SB, Beygi S, Shokraneh F, Hagen EM, Rahimi-Movaghar V. Incidence of traumatic spinal cord injury worldwide: a systematic review. Eur Spine J. 2015;24:905–18.

Heidari P, Zarei MR, Rasouli MR, Vaccaro AR, Rahimi-Movagar V. Spinal fractures resulting from traumatic injuries. Chin J Traumatol (Engl Ed). 2010;13:3–9.

Moradi-Lakeh M, Rasouli MR, Vaccaro AR, Saadat S, Zarei MR, Rahimi-Movaghar V. Burden of traumatic spine fractures in Tehran, Iran. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:789.

Moosavi N-S, Emami Z, Vaccaro AR, Rahimi-Movaghar V. Long-term follow-up study of patients with spinal cord injury. Neurosciences 2013;18:385–7.

Azadmanjir Z, Rahimi-Movaghar V, Jazayeri B, Ghodsi M, Sharif-Alhoseini M, Zarei M-R, et al. P16: Iranian Quality Registry of Spinal Cord Injury, Key Considerations for Implementation. Neurosci J Shefaye Khatam. 2015;2:66.

Naghdi K, Azadmanjir Z, Saadat S, Abedi A, Koohi HS, Derakhshan P, et al. Feasibility and Data Quality of the National Spinal Cord Injury Registry of Iran (NSCIR-IR): A Pilot Study. Arch Iran Med. 2017;20:494–502.

Kalankesh LR, Dastgiri S, Rafeey M, Rasouli N, Vahedi L. Minimum Data Set for Cystic Fibrosis Registry: a Case Study in Iran. Acta Inform Med. 2015;23:18–21.

Kowal PR, Wolfson LJ, Dowd JE. Creating a minimum data set on ageing in sub-Saharan Africa. Southern African. J Gerontol. 2000;9:18–23.

Cai S, Mukamel DB, Veazie P, Temkin-Greener H. Validation of the Minimum Data Set in identifying hospitalization events and payment source. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2011;12:38–43.

Spisla C. Enhancement of interoperability of disaster-related data collection using Disaster Nursing Minimum Data Set. Stud Health Technol Inf. 2009;146:780–1.

Rutledge R. The goals, development, and use of trauma registries and trauma data sources in decision making in injury. Surgical Clin North Am. 1995;75:305–26.

Noonan V, Kwon B, Soril L, Fehlings M, Hurlbert R, Townson A, et al. The Rick Hansen spinal cord injury registry (RHSCIR): A national patient-registry. Spinal Cord 2012;50:22–7.

Rick H SCI Registry: Rick Hansen Institute. http://www.rickhanseninstitute.org/work/our-projects-initiatives/rhscir/64-our-work/our-projects-initiatives/rick-hansen-sci-registry. Accessed 14 Jun 2015.

Rick H. Spinal Cord Injury Registry Dataset. Version 2.2. Canada: Rick Hansen inistitiue; 2013.

Dvorak M. Protocol: Rick Hansen Spinal Cord Injury Registry (RHSCIR). Canada: Rick Hansen inistitiue; 2013.

Bickenbach J. International perspectives on spinal cord injury. Geneva: World Health Organization, International Spinal Cord Society; 2013.

Interational Spinal Cord Society: International SCI Data Sets. https://www.iscos.org.uk/international-sci-data-sets. Accessed 20 Jun 2015.

Biering-Sørensen F, Charlifue S, DeVivo M, Noonan V, Post M, Stripling T, et al. International Spinal Cord Injury Data Sets. Spinal Cord 2006;44:530–4.

DeVivo M, Biering-Sorensen F, Charlifue S, Noonan V, Post M, Stripling T, et al. International Spinal Cord Injury Core Data Set. Spinal Cord 2006;44:535–40.

Ghaneie M, Rezaie A, Ghorbani N, Heidari R, Arjomandi M, Zare M. Designing a minimum data set for breast cancer: a starting point for breast cancer registration in Iran. Iran J public health. 2013;42:66–73.

Evans SM, Nag N, Roder D, Brooks A, Millar LJ, Moretti KL, et al. Development of an international prostate cancer outcomes registry. BJU Int. 2016;117:60–7.

Kalankesh LR, Dastgiri S, Rafeey M, Rasouli N, Vahedi L. Minimum Data Set for Cystic Fibrosis Registry: a Case Study in Iran. Acta Informatica. Medica 2015;23:18–21.

Ahmadi M, Alipour J, Mohammadi A, Khorami F. Development a minimum data set of the information management system for burns. Burns 2015;41:1092–9.

Ahmadi M, Mohammadi A, Chraghbaigi R, Fathi T, Baghini MS. Developing a minimum data set of the information management system for orthopedic injuries in Iran. Iran Red Crescent Med J. 2014;16:e17020.

Svensson-Ranallo PA, Adam TJ, Sainfort F. A Framework and Standardized Methodology for Developing Minimum Clinical Datasets. AMIA Summits on Transl Sci Proc. 2011;2011:54–8.

Tee J, Chan P, Rosenfeld J, Gruen R. Dedicated spine trauma clinical quality registries: a systematic review. Glob Spine J. 2013;3:265–72.

Discharge Abstract Database (DAD) Metadata: Canadian Institute for Health Information. https://www.cihi.ca/en/types-of-care/hospital-care/acute-care/dad-metadata. Accessed 19 Aug 2016.

Hospital Mental Health Database (HMHDB) Metadata: Canadian Institute for Health Information. https://www.cihi.ca/en/types-of-care/specialized-services/mental-health-and-addictions/hospital-mental-health-database. Accessed 20 Aug 2016.

Home Care Reporting System (HCRS) Metadata: Canadian Institute for Health Information. https://www.cihi.ca/en/types-of-care/community-care/home-care/hcrs-metadata. Accessed 20 Aug 2016.

National Rehabilitation Reporting System (NRS) Metadata. https://www.cihi.ca/en/types-of-care/hospital-care/rehabilitation/national-rehabilitation-reporting-system-nrs-metadata. Accessed 20 Aug 2016.

Continuing Care Reporting System (CCRS) Metadata: Canadian Institute for Health Information. https://www.cihi.ca/en/types-of-care/hospital-care/continuing-care/continuing-care-reporting-system-ccrs-metadata. Accessed 20 Aug 2016.

AIHW. Australian Spinal Cord Injury Register (ASCIR), Version 2.0. Adelaide: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare’s (AIHW) National Injury Surveillance Unit (NISU); 2012.

O’Connor P. Development and utilisation of the Australian spinal cord injury register. Spinal Cord 2000;38:597–603.

Gosling C, Gabbe B, Jennings P, Cameron P. Scoping study to enhance spinal cord injury data connectivity within Australia and internationally; Phase One Report. Australia: Monash University; 2011.

Widerström-Noga E, Biering-Sørensen F, Bryce TN, Cardenas DD, Finnerup NB, Jensen MP, et al. The International Spinal Cord Injury Pain Basic Data Set (version 2.0). Spinal Cord 2014;52:282–6.

Dvorak MF, Wing PC, Fehlings MG, Vaccaro AR, Itshayek E, Biering-Sorensen F, Noonan VK. International spinal cord injury spinal column injury basic data set. Spinal Cord 2012;50:817–21.

Dvorak MF, Itshayek E, Fehlings MG, Vaccaro AR, Wing PC, Biering-Sorensen F, et al. International spinal cord injury: spinal interventions and surgical procedures basic data set. Spinal Cord 2015;53:155–65.

Krassioukov A, Alexander MS, Karlsson AK, Donovan W, Mathias CJ, Biering-Sørensen F. International spinal cord injury cardiovascular function basic data set. Spinal Cord 2010;48:586–90.

Biering-Sørensen F, Krassioukov A, Alexander MS, Donovan W, Karlsson AK, Mueller G, et al. International spinal cord injury pulmonary function basic data set. Spinal Cord 2012;50:418–21.

Bauman WA, Biering-Sørensen F, Krassioukov A. International spinal cord injury endocrine and metabolic basic data set (version 1.2). Spinal Cord 2012;50:567.

Krogh K, Perkash I, Stiens SA, Biering-Sørensen F. International bowel function basic spinal cord injury data set. Spinal Cord 2009;47:230–4.

Biering-Sørensen F, Craggs M, Kennelly M, Schick E, Wyndaele JJ. International Lower Urinary Tract Function Basic Spinal Cord Injury Data Set. Spinal Cord. 2008;46:325–30.

Charlifue S, Post MW, Biering-Sørensen F, Catz A, Dijkers M, Geyh S, et al. International spinal cord injury quality of life basic data set. Spinal Cord 2012;50:672–5.

Biering-Sørensen F, Burns AS, Curt A, Harvey LA, Jane Mulcahey M, Nance PW, et al. International spinal cord injury musculoskeletal basic data set. Spinal Cord 2012;50:797–802.

Biering-Sørensen F, Bryden A, Curt A, Friden J, Harvey LA, Mulcahey MJ, et al. International Spinal Cord Injury Upper Extremity Basic Data Set. Spinal Cord 2014;52:652–7.

Karlsson AK, Krassioukov A, Alexander MS, Donovan W, Biering-Sørensen F. International spinal cord injury skin and thermoregulation function basic data set. Spinal Cord 2012;50:512–6.

Nejat S, Montazeri A, Holakouie Naieni K, Mohammad K, Majdzadeh S. The World Health Organization quality of Life (WHOQOL-BREF) questionnaire: Translation and validation study of the Iranian version. J Sch Public Health Inst Public Health Res. 2006;4:1–12.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the Deputy of Research and Technology, Ministry of Health and Medical Education of Iran for supporting the NSCIR-IR. Also, we thank the Office of University and Industry Communication in Tehran University of Medical Sciences, and all experts who provided insight and expertize that greatly assisted the research.

Funding

NSCIR-IR has been financially supported by Deputy of Research and Technology, Ministry of Health and Medical Education (MOHME) of Iran.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

ZA wrote the draft of the paper, designed and implemented the NSCIR-IR project from idea to deployment, and also has a major role in data set and case report forms development. ZA made major revisions to the paper and its appendix. VR-M designed and implemented the NSCIR-IR project from idea to deployment including data set development and also made major revisions to the paper. SBJ contributed to the design of NSCIR-IR project and also made major revisions to the paper. RHA, GO, VN, ARV, ECB, MS, MS-A, HP, EF, and ZG contributed to revision of the manuscript. KN contributed to the NSCIR-IR project as registrar. GK prepared the appendix. ZK, HS, KZ, JAK, SS, and FS were members of the expert panel and contributed to the paper’s revision. RHA refined the paper according to final comments and modifications.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

This study was approved by Research Ethics Committee of Tehran University of Medical Sciences as a part of National Spinal Cord Injury Registry study.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Azadmanjir, Z., Jazayeri, S.B., Habibi Arejan, R. et al. The data set development for the National Spinal Cord Injury Registry of Iran (NSCIR-IR): progress toward improving the quality of care. Spinal Cord Ser Cases 6, 17 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41394-020-0265-x

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41394-020-0265-x

This article is cited by

-

Dos and don’ts in designing a computerized oral and lip squamous cell cancer registry

BMC Health Services Research (2023)

-

Development and evaluation of a customized checklist to assess the quality control of disease registry systems of Tehran, the capital of Iran in 2021

BMC Health Services Research (2023)

-

The international spinal cord injury pain basic data set (version 3.0)

Spinal Cord (2023)

-

An evaluation of the representativeness of a national spinal cord injury registry: a population-based cohort study

Spinal Cord (2021)