Abstract

Among scholars in sustainability science, there is an increasing recognition of the potential of place-based research in the context of transformative change towards sustainability. In this research, researchers may have a variety of roles; these are determined by the researcher’s engagement with the subject, the inherent theoretical, normative and methodological choices he or she makes, the researcher’s ambitions in contributing to change, and ethical issues. This article explores the varied roles of research fellows within the European Marie Curie ITN research program on sustainable place-shaping (SUSPLACE). By analysing 15 SUSPLACE projects and reflecting on the roles of researchers identified by Wittmayer and Schäpke (Sustain Sci 9(4):483–496, 2014) we describe how the fellows’ theoretical positionality, methods applied, and engagement in places led to different research roles. The methodology used for the paper is based on an interactive process, co-producing knowledge with Early Stage Researchers (fellows) of the SUSPLACE consortium. The results show a range of place meanings applied by the fellows. Varied methods are used to give voice to participants in research and to bring them together for joint reflection on values, networks and understandings, co-creating knowledge. Multiple conceptualisations of ‘sustainability’ were used, reflecting different normative viewpoints. These choices and viewpoints resulted in fellows each engaging in multiple roles, exploring various routes of sustainable place-shaping, and influencing place-relations. Based on our findings we introduce a framework for the ‘embodied researcher’: a researcher who is engaged in research with their ‘brain, heart, hands and feet’ and who integrates different roles during the research process.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The transformative turn in sustainability research (Dentoni et al. 2017) and debates (Blythe et al. 2018; UN Agenda 2030 for Sustainable Development 2015, p. 11) shares an understanding that scientific knowledge itself cannot solve the problems we face, and that other ways of doing science are needed. As a consequence, and building on second-order (Mode 2) research, there has been a revival of participative and action research (Bradbury-Huang 2015; Rowell et al. 2017), and an increase of attention on engaged scholarship, citizen science and inter- and transdisciplinary research, supported by a variety of funding schemes. Particularly prominent are the co-production processes involving different types of knowledge including non-academics (Mauser et al 2013). As several authors argue, this way of doing science extends the role of researchers from objective observers to more reflexive researchers or even active change agents who aim to support transformative change (Pohl et al. 2010; Lang et al. 2012; Popa et al. 2015; Reason and Bradbury 2008; Bradbury-Huang 2015; Schneider et al. 2019). Researcher’s roles have been discussed in light of debates on sustainability transitions (Wittmayer and Schäpke 2014; Bartels and Wittmayer 2014), co-production (Pohl et al. 2010), real-world laboratories (Hilger et al. 2018) or complex systems literature (McGowan et al. 2014). Yet, while place-based approaches are increasingly favoured in science and recognised and key for sustainability transformations (Horlings 2018), there is still a need for a more in-depth understanding of the role of researchers engaged in this type of sustainability research.

We argue that place-based research, as a particular approach to sustainability research, portrays distinct ways of engaging with research. Place-based research assumes that the ability to adapt effectively to current environmental and resource vulnerabilities demands solutions that build on the specific resources, assets, capacities and distinctiveness of places (Healey et al. 2003; Horlings 2017; Marsden and Bristow 2000; Murdoch 2000; Roep et al. 2015; Shucksmith 2009; Tomaney 2010). Here sustainable place-shaping is a new concept (Roep et al. 2015; Horlings 2019; see also the editorial) that refers to the capacity to re-localize and re-embed daily lived practices in social-ecological systems and place-based assets, thus altering the relations between people and their environment. The practices are driven by the energy and imagination of people while grounded in the ecology and materiality of places (Marsden 2012). Similar to other practice theorists (e.g. Giddens 1994; Schatzki et al. 2001), this perspective acknowledges that ‘structure’ (sociocultural, political-economic and ecological relations) is imbricated in everyday actors' practices’, propelling’ everyday life (see Horlings 2018). Actors are however capable to both reproduce and change these structural relations. Processes of sustainable place-shaping thus connect people to place (Horlings 2016). Via the practices people are involved in they change social relations in networks on multiple scales thus linking places to each other. Place is also relevant as site of social interaction where people can have dialogues about the perceived qualities of their place, what they value, or how to build a place narrative for the future (Grenni et al. 2019).

Research on place-shaping practices inevitably invites researchers to engage in places to understand these practices; this results in varied, sometimes conflicting, positions and tensions and raises ethical issues about doing research. While there is a growing body of research focused on the researcher’s role, identity and positionality in sustainability research (Alvesson and Sköldberg 2011; Hilger et al 2018; Loorbach et al. 2017; Popa et al. 2015; Schneider et al. 2019), the potential and value of different roles academics take in sustainability research, when and why they take up these roles, and the obstacles and tensions they face, remain unresolved issues that need further exploration (e.g. Hilger et al 2018). This kind of analysis is also essential for the quality and credibility of sustainability science.

This paper thus aims to understand and reflect upon the role of researchers in the context of place-based research under the wide umbrella of sustainability research. The paper is centered on the following questions: How do researchers practice and engage in place-based sustainability research and what kind of roles do they adopt in the research process? To answer these questions we analyse 15 research processes conducted under an European funded research program (SUSPLACE) along three entry points:

- 1.

How do researchers engage in places and what does place-based research mean for them?

- 2.

How do they position their research theoretically and normatively with regard to sustainability?

- 3.

Which methods and methodological approaches do they apply?

We argue that the roles that the fellows take are influenced by their place-engagement, theoretical positioning and the applied methodology and methods. We build our study on the work of Wittmayer and Schäpke (2014) who provide a typology/categorisation of the roles of researchers in sustainability science. Using these ‘ideal type roles’ we reflect upon the research process of 15 Early Stage Research (named fellows) of the SUSPLACE program identifying tensions and challenges experienced.

The SUSPLACE program (https://www.sustainableplaceshaping.net) is an European Marie Curie (ITN) funding scheme covering the period of 2015–2019. It analysed practices, pathways and policies that can support place-based approaches to sustainable development. The central questions that guided the program were: What are place-based resources? How can the full potential of places and people be utilized to enhance place-shaping processes? How can fellows support such processes? The theoretical basis of SUSPLACE was derived from the relational notion of place which assumes that places are not merely geographical locations, but the outcome of practices, social relations and interactions, stretching beyond geographical or administrative boundaries (Massey 1991, 2004, 2005; Woods 2011; Pierce et al. 2011; Heley and Jones 2012). The fellows involved in SUSPLACE all developed their own approaches and perspectives to sustainable place-shaping, some more loosely and others more strongly tied to the initial theoretical base of the program.

The overall aim of SUSPLACE was to train the fellows in innovative approaches to study sustainable place-shaping practices. The SUSPLACE-program supported the fellows with training to learn skills in collaboration, participative research, interdisciplinary team work, and multi-method research. Overall, the program provided a setting where place-based research, the roles of fellows and lessons learnt were regularly discussed during joint events and meetings. The inter- and transdisciplinary approach of the program, as well as the continuous learning and reflection throughout, thus makes SUSPLACE an interesting empirical case to explore researchers’ roles in place-based sustainability research.

The paper is structured as follows: “Introduction” introduces Wittmayer and Schäpke’s (2014) typology and “Exploring the roles of researchers in place-based sustainability research” elaborates on the issues of reflexivity and normativity in relation to sustainability and transformation research in the context of place. “Methodology” continues by explaining the methodology used for this study. The “Results” explores how the fellows engaged in different places, positioned themselves theoretically in the context of place-based sustainability research, and put their research into practice, including the methods they used. As we will show, these aspects influenced the roles they employed in their research. We interpret the results by introducing the term ‘embodied researcher’, which illustrates how place-based researchers engage in research with their ‘brain, heart, hands and feet’. We conclude by elaborating on how these findings might be relevant for the current debate on sustainability science and transformative change.

Exploring the roles of researchers in place-based sustainability research

The roles of the researchers in sustainability action research

The roles of researchers have been discussed in particular in the context of participatory action research and feminist research (Clough 1992; Fonow and Cook 1991; Oakley 1981). The researcher’s “role” is essential as it defines a number of issues in the research: how researchers collect, analyse and interpret data; how they position themselves in relation to the research problem, the place, and towards the participants; the kind of change they attempt to support; and lastly how they reflect on their position and subjectivity. Besides these scientifically driven aspects, there are also other factors which influence the kind of roles adopted by researchers. These include personality (Miah et al. 2015; Carew and Wickson 2010), internal motivations and gender (Hilger et al 2018), and more technical factors such as resource availability, project group organization and external expectations (Hilger et al 2018). In this study, we focus on the scientifically driven factors while acknowledging these other aspects also have an effect on the role a researcher takes.

There are some typologies and frameworks that aim to analyse the different roles of the researcher as well as studies that point out how the roles should be reflected in sustainability research (see e.g. Pohl et al. 2010; Wuesler 2014; Schneider et al. 2019). This paper uses the frame introduced by Wittmayer and Schäpke (2014) for understanding different roles of researchers in action research in the context of sustainability transitions. These roles are determined by the level of ownership of the problem, the manner by which researchers deal with sustainability and power dynamics in the group, and by the actions the researchers take (see Table 1, adapted from Wittmayer and Schäpke 2014, p. 488). Here we briefly describe the essence of each role. A reflective scientist is closest to the conventional researcher, acting as an external observer, not actively intervening the process studied. A process facilitator is responsible for the design and implementation of short-term actions, and in this way engaging for example in dynamics between the participants and the learning that may take place. A knowledge broker mediates between different perspectives related to the issue at stake but also aims to make sustainability relevant for different stakeholders and tangible in the given context. The role of change agent refers to the explicit participation of the researcher in processes of change. The researcher seeks to motivate and empower participants to trigger change. Finally, acting as a self-reflexive scientist is being continuously reflexive about one’s own normativity and positionality, while also prone to personal transformation during the research process (Wittmayer and Schäpke 2014, pp. 487–489). Overall, the activities performed in different roles during the actual research work are complex and fluid. Consequently, instead of seeing these roles as separate, we understand them as a continuum, showing the level of engagement of the researcher during the research process.

We contend that Wittmayer and Schäpke’s typology covers well the possible roles the researchers working on sustainable place-shaping may have in their research. Thus, we use this frame to explore more in depth, how are these roles deployed in sustainable place-shaping research and in concrete places through time. In particular, we are interested in how the researchers reflect on their roles, their positioning towards “place”,“sustainability” and “transformation” and the ethical implications they perceive while developing place-based sustainability research. In the following sections, we explore these issues.

Reflexivity in sustainable place-shaping research

Reflexivity in research can appear in different forms (Lumsden 2019). We are interested in ‘self-reflexivity’ by which the researcher’s practices become an expression of their personal interests and values, acknowledging the reciprocal relationship between life experiences and motivations; as well as in ‘functional reflexivity’ which involves reflection on the nature of the research project, including the choice of method and the construction of knowledge revealing underlying assumptions, values and biases.

Reflexivity is especially relevant in the context of sustainability research, as sustainability has been interpreted in various ways, often hiding normative viewpoints and political intentions. This calls for taking normativity seriously, and ensuring that researchers are aware of how they position themselves in the sustainability discourse. Sustainability research in general aims to support societal change. Yet researchers’ interpretations may focus for example on all or some of the core principles of sustainability (ecological integrity, intra or inter-generational equity) or on environment-development relations; in some cases sustainability may be used as an overarching concept (Wuesler 2014; Frank 2017). The definitions employed can emerge from researchers’ own conceptions (values) stakeholders’ perceptions or from processes of a deliberation or through contextualisation (Wuesler 2014). Furthermore, research may also differ in whether it aims to support sustainability by analysing it or actively support change by participating in societal change processes (Miller 2013; Miller et al. 2014). In any case, the interpretations of sustainability inevitably reflect the values of the researchers and their commitment to sustainability goals, thus affecting their practices.

As we argued in the introduction, we assume that a place-based approach is a useful lens to study the transformative processes towards creating more sustainable places. Scholars have conceptualized the concept of transformation in various ways. A detailed literature review is beyond the scope of this paper but we mention here some of the main differences in how transformation has been framed in science. Transformation can be understood as an organised, top-down managed process towards a certain goal in a given sector, as a radical bottom-up change across sectors, or as something emerging from these two ends of the spectrum (Feola 2015; Blythe et al. 2018). For example, numerous operationalizations of the concept of transformation have been elaborated (Blythe et al. 2018): the transition approach (e.g. Geels and Schot 2007; Geels 2014; Geels et al. 2017; Loorbach 2010), the social-ecological system transformation within planetary boundaries approach (e.g. Berkes et al. 2003; Folke et al. 2005; Olsson et al. 2014; Westley et al. 2013; Rockström et al. 2009); the sustainability pathways approach (Leach et al. 2012), and the transformative adaptation approach (O’Brien 2012; Pelling et al. 2015). Stemming from different disciplines or schools of thought, there are various understandings of transformation, depending on the types of knowledge included and generated, the importance granted to the role of human agency and the role of researchers in the transformative processes (Feola 2015). Scholars have attempted to combine these diverse conceptualisations of sustainability and transformations in many ways resulting in a myriad of perspectives and normative positions.

Most of these combinations refer to a procedural approach (Miller 2013, p. 289): a methodological- oriented approach that focuses on how sustainability comes to be defined and how pathways are developed to pursue it, leaving room for a researcher to take a role and bringing their values and normative positions into these processes. In order for research to support transformation, it is important to balance ‘relationality’ and ‘criticality’ (Bartels and Wittmayer 2014). Good relationships are needed for critique to be tolerated and have an effect, while at the same time a critical stance is needed for those relationships to generate transformative ideas and sustainable practices. Research which aims to support transformation might change researchers themselves, as in the role of “self-reflexive scientist”. A willingness to change can be seen as an ethical choice when engaging in place-based, sustainability and action research. This choice comes with the aim of supporting a more sustainable society via changing our own practices and worldviews as humans and researchers. In action research, these types of changes are called ‘process- impacts’ which include changes in modes of collaboration, relationships, everyday practices and worldviews (Campbell and Vanderhoven 2016, Luederitz et al. 2017). Thus, in the context of place-based research, it is important to explore how researchers relate to the places they work in, the quality of relations they build, and how this influences the room for criticality and in the end the potential for transformation.

Methodology

Data-collection

The methodology used for the paper is based on the design of an interactive and iterative process, co-producing knowledge within the SUSPLACE program. Consortium members were invited to reflect on how the theoretical contributions of the program could be summarized and which theoretical lessons could be derived from the 15 research projects. The role of the 15 fellows was to provide information regarding their own research process online and via mail (see below the specific information which was gathered). The authors of this paper, two research fellows and two supervisors, were responsible for designing and organizing the data collection, exploration and reflection. All the fellows and other consortium members were able to comment and reflect on the results. The process of data collection and reflection consisted of several phases and started in September 2017 and finished in August 2019. The data constituted:

Online project information. An online tool was developed by one of the non-academic partners called the ‘mastercircle’ (see Horlings et al. 2019, p.65) and suitable for gathering information about the projects and facilitating discussions among all consortium members in multiple rounds. A tailor-made online survey with qualitative open questions was set up. The survey resulted in descriptive information about theories, methods and case studies for each of the 15 research projects (see Table 2). The theoretical section included information on the following topics: how place was operationalised; which place-shaping practices were studied; how the fellows understood these to be linked to sustainability and transformation; and moral and ethical positioning. When clarification or additional information was needed, the authors gathered this via mail. The analysis of the text was done through a thematic analysis resulting in a draft synthesis document. This document provided the main basis of the paper and served as input for a subsequent face-to-face workshop.

Table 2 Description of the 15 SUSPLACE research projects Transcripts from the workshop with the fellows organized in September 2018 in Riga. The aim of the workshop was to collect additional and more detailed information on three specific topics discussed in this paper: (1) How do researchers engage in places and what does place-based research mean for them? (2) How do they position their research theoretically and normatively with regard to sustainability? and (3) Which methods and methodological approaches do they apply?

For each of the topics key questions were formulated to guide the discussion. The workshops were facilitated by the author and resulted in a ‘synthesis report’. The role classification of Wittmayer and Schäpke (2014) was used as a frame for discussions surrounding the roles taken by fellows.

Insights retrieved from the SUSPLACE Final Event in Tampere in August 2019, where the roles of researchers in different settings were discussed in relation to transformative methods.

The authors structured and interpreted the data in several analytical rounds. During the stages of data-collection online, and during the workshop in Riga the fellows were asked consent with regard to the use of their project information and citations to synthesize the lessons learnt from SUSPLACE. Draft products such as the descriptive ‘synthesis report’—used as basis for this paper—were shared with the fellows. Where relevant, citations and non-descriptive information in the next sections which can be traced back to the specific projects, have been anonymized.

Description of cases

The study is informed by the 15 research projects carried out by fellows who pursue a PhD and are part of the SUSPLACE program. The 15 fellows investigated a range of cases and practices in different European contexts. While acknowledging the varied definitions given to social practice in the literature, a practice is defined here as an organized and recognisable socially shared bundle of activities that involves the integration of a complex array of components: material, embodied, ideational and affective (Schatzki et al. 2001). Practices are sets of ‘doings and sayings’ that involve both practical activity and its representations (Warde 2005, p. 134). Some of the research fellows focused on one place-shaping initiative, while others analyzed particular practices in various places or compare places/regions. In Table 2 we provide an overview of all the projects, the context and country of the research, the methods used and the type of place-shaping practices that were studied.

Most of the fellows carried out participative research. This has ethical consequences. SUSPLACE developed an ethical policy and data management plan which was implemented as part of the individual research designs, including an information sheet and letter of consent for participants. Ethical considerations further include aspects such as attention for the inclusion and exclusion of actors, vulnerability of actors and (hidden) power relations. As the fellows performed research in a foreign country, ethical questions can be raised such as: how to ensure a meaningful engagement in places when the fellow—being a foreigner- is not familiar with the biophysical, political-economic and socio-cultural context, speaks English instead of native language, or uses a translator? How to become culturally aware and sensitive to cultural differences and power imbalances in interaction, communication and behaviour with research participants? In other words, how does (a lack of) ‘cultural intuition’ (Delgrado-Bernal 1998) influence a research process?

The assistance of native supervisors and non-academic partners was valuable in implementing the research in such a way that it was sensitive to the above issues. How to do place-based research when “dis-placed” in another country is particularly pertinent because much of today’s research is developed by international researchers or through international partnerships; as such these reflections can be useful for future fellows. In line with Pillow (2003) we point out here that being an ‘insider’ in terms of already belonging to or having socio-cultural commonalities with the community/place researched does not necessarily render the research ‘egalitarian’ (Bernal 1998; Johnson-Bailey 1999; Villenas 1996; 2000). Power issues are always embedded in a research process and both ‘insider’ as well as ‘outsider’ researchers navigate dual identities and dual positions of power (Brayboy 2000; Chaudhry 2000; Motzafi-Haller 1997; Villenas 1996; 2000). Furthermore, encounters with ‘otherness’ and co-creating knowledge in a space characterized by diversity might in itself be a valuable process-impact of research projects that crosses cultural boundaries.

Results

In this section, we analyze how the 15 fellows carried out their research by focusing on how they conceptualised their research engagement, which normative positions underlie their research, and how this translated into different methods.

Engagement in places

Interpretations of place

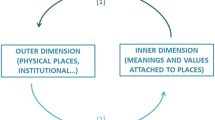

The SUSPLACE research was based on a relational approach to places. This means that places are not defined by administrative or geographic boundaries, but are seen as assemblages of social relations, continuously changing as a result of economic, institutional and cultural transformation. This approach emphasizes the linkages between geographical scales.

Place was defined by fellows as composed of the material world, the practices of human and non-human beings, and the meanings that humans attach to practices; all three are ordered in particular constellations of relations shaping identifiable places for people. Most fellows explicitly acknowledge the material dimension of places supporting the ‘reconstructive turn’ (see for example Latour 2004; Massey 2005). Fellows also analyzed the relationships between the material word (including humans and non-humans) (social) practices and the inner self. As one fellow stated: “a shift in consciousness [towards an ecological consciousness or consciousness of interbeing] takes place in the interaction between the self, the social and the material” (see also Newman 2014 in Pisters et al. 2019). A range of (relational) interpretations of place were used in the research projects, as described below.

Places as an actor-arena

Although recognizing the materiality of places, the varied opinions of stakeholders, and actions related to shaping social-material relations were an important focus of attention in the research projects. Fellows looked at places as arenas of interaction between multiple actors in a geographical or policy arena. They were interested in tracing and mapping practices, participation and co-creation between actors, as well as connectivities in and in between organizations, governance structures and socio-political or economic systems. Project #6 on wind energy citizen initiatives provides an example of how new institutional arrangements between civil society, private actors and governments can support or enable collective citizens’ initiatives which aim to increase renewable energy production. Similarly, project #5 on re-grounding practices of linen production in Portugal explored how local actors work together and mobilize local resources, knowledge and capacities to shape networks in rural areas (Vasta et al 2019).

Place as constructed via meanings, images and perceptions

Some fellows focused on place meanings, images and perceptions. They analyzed how place is articulated in individual and collective discourses and narratives and how these narratives influence attitudes and behaviours. For example, project #3 on sense of place in a small industrial (rural) town in Finland implemented a participatory approach with citizens to explore their sense of place with the aim of building a place narrative that can be used to envision pathways for future sustainability (see also Grenni et al. 2019).

Place as an embodied experience

Other projects turned it around by looking at how embodied experiences in places and reflections can lead to a new consciousness and way of ‘being in place’. One of the fellows stated: “Looking at a place or an issue from a new perspective—such as the ecological self, the perspective of uncertainty, or deep care for place—can open up spaces of possibility…”. Another fellows mentioned about embodied experiences that “these can lead to the emergence of a consciousness of ‘interbeing’ where humans feel part of ‘a living system within other systems of humans and non-humans”.

For instance, project #2 on eco-villages in Finland and Portugal analyzed how people living in an intentional community experience and feel the place. Project #9 on leadership designed and applied social engagement approaches (via workshops applying art-based methods) that can trigger shifts in consciousness of the self, or mindset shifts.

Choosing and adapting the research approach

The notion of relational places translated into different research approaches. First, in contrast to the idea of the positivist and objective researcher, place-based fellows see themselves as “human beings”, as part of the networks of relations in a place. For example, one of the fellows described her role as ‘’an outgoing person, an activist, community gardener, teacher, as young” thereby recognizing her own biases, wishes and capabilities. Fellows valued spending time in the researched places as human beings, creating personal bonds with the researched subjects as a way of “becoming a participant in the community’s life […]’’ which allows ‘’for a deep relation with the key actors, gaining trust". ‘Relationality’ applies not just to place-based research, but is also a key dimension of action research, combined with ‘criticality’ (Bartels and Wittmayer 2014). Related to this, it is clear that the engagement of fellows always influenced in some way or another the relations that shape these places. One of the fellows used for example personal connections as a (transpersonal) research method itself: “I allow myself to connect to the research and my research participants in a personal and emotional way, which fosters connection between me and the participants and a sense of shared human experience. This deepens our conversations and my understanding of the nature of their experience”.

Becoming more conscious of their context-specific capabilities with respect to the places they research, fellows adapted their research approach accordingly. For instance some fellows started off with the ambition of being a change agent, and gradually realized that this role was not feasible, taking up instead the role of process facilitator, with the aim of starting a discussion with different stakeholders on a specific topic, as was done in the project with youth in Wales (#14) (see also Axinte et al 2019). This is related to the fact that SUSPLACE foresaw international mobility such that many fellows were unfamiliar with the language and culture and were less prepared to practice action right away. Also, the level of power the fellow has (or perceives to have) for action depends on the research area, as experienced by a fellow: “I think my topic and the level I work leaves very little space for me to do something meaningful…the discussions, plans and strategies happen at a highly political level to which I don’t have access and almost zero capacity to contribute to”. Yet, while some fellows took on the role of reflective scientist because of a self-awareness of their own personality and capabilities at that specific stage of research, others developed an ambition of being change agents in the process of acquiring knowledge, networks and skills through their research. Most of the fellows agreed that there is not a clear distinction between the roles and some felt they engaged in all roles.

Ethical implications of place engagement

The fact that fellows consider themselves as being part of place relations translated into an ethical responsibility in contributing to change in the places and communities they research. Even if most fellows do not consider themselves to be actively engaged as change-agents, they intend to start or support change in some way. One of the fellows formulated this as: “by asking questions and introducing topics for discussion, […] contributing to e.g. raising awareness, inducing changes in the way people think about issues and perceive themselves, and helping people to realize they have the power to shape their places”. This responsibility developed throughout the research as a learning process. To explain this a fellow referred to the notion of response-ability of Donna Haraway. Response-ability does not refer to the liberal humanist obligation to be responsible for one’s own choices but our ability to respond ethically to the demands of the many others with whom we share this world (Haraway 2010). The fellow argued that learning from people and from places via experimentation is key to cultivating response-ability: “I want to do things differently, through practice and iterative learning, being open to experimentation and failure, until I eventually do things better…. This being said, it’s great to see that I am, voluntarily or not, influencing the way my communities of practitioners perceive themselves, their work and their collaborators”.

Related to the above, if one considers the researcher as being part of place, the ‘how’ of doing research (the way in which research is carried out, including researchers’ interaction with places and participants) matters and can in itself support sustainability transformations: “If I think of social justice and inclusion, I can certainly say that the ‘way’ we do things is what counts, and the ‘how’ is really what matters to create a better society”. This relates to the ethics of willingness to change from the side of researchers, and the importance of process- impacts, as mentioned in “Exploring the roles of researchers in place-based sustainability research” of this paper.

As such, fellows were eager to engage participants in places in a meaningful way, highlighting that research should be driven by the needs of the people in places and should be attentive to reciprocity between fellow and research participants, as for example was argued in the projects on commoning land in Portugal (#4), green care in Finland (#13) and social entrepreneurship in Latvia (#12). During the data collection stage, this translated into allowing participants the freedom to discuss what matters to them and to co-create, adapt and shape the research together. This research approach requires a constant process of critical self-reflection, acknowledged by all fellows as an important part of the process. For example, self-reflection is needed to design approaches that give voice to all groups, empower vulnerable ones and cultivate reciprocity with research subjects as was for example shown in the project on green care services in Finland (#13) (see also Moriggi 2019; Moriggi et al. forthcoming). This combines the more solution-oriented approach of Wittmayer and Schäpke (2014) of giving voice to all groups while at the same time hinging on a more radical form of action research (Jhagroe 2018) by explicitly empowering vulnerable groups. Along with Lumsden (2019), fellows argued that self-reflection is needed to undertake research rooted in explicit values and normative positions such as reciprocity, empathy, and even aesthetics. As such, most fellows referred to a strong process of self-reflection upon their own positionality and normativity; this continues throughout all stages of the research and is combined with reflection prior and after each engagement with the place/process. At the start of the research process, some fellows took time to explore the variety of positions they could take and what role would suit them best. Others already had a clear idea of their position from the onset and the research allowed them to put their normative positions into practice, choosing theories and methods which matched their positions. For most research fellows the SUSPLACE program represents a turning point in their academic work and even in their lives. They experienced a process of self-transformation by becoming aware of the different assumptions and roles a researcher has, understanding the limits of (academic) research when reflecting on theories and approaches to sustainability, and engaging with places and people. Self-reflection and self-transformation allowed fellows to move from “observation to action”. They thus (re-) considered their personal role in supporting sustainability pathways.

Normative positions and theoretical choices

All fellows in SUSPLACE have a strong normative position towards sustainability. Here we provide a distinction between the main positions.

Sustainability providing ecological limits to society and economy

Some fellows placed more emphasis on the ecological limits and boundaries within which human activities and societies should remain (Steffen et al. 2015). Research is seen as a means to find out what the boundaries are, how societies can be organized in ways that respect those boundaries, and what the implications are for different groups of people. This translates into research projects which explicitly challenge dominant regimes and capitalist market economies and stress that sustainability is always embedded in a political environment and is essentially a policy or political concept. Fellows turned to the analysis of post-capitalism, to social innovation in the project on place-based policies (#15), de-growth models in the project on permaculture in Latvia (#11), political and social economy (#12), circular economy in the food waste project in Brussels (#10) and diverse economies and commoning in the project on common forest land in Portugal (#4) (see also Nieto-Romero et al. 2019). This critical stand aims to stress underlying systemic and political processes, as one of the fellows expressed: “the financial aspect of the globalizing world tends to be overlooked for multiple reasons, like the perceived murkiness of the financial world, as well as the seemingly distant connection to local, sustainable projects.’’ Another fellow analyzed projects of sustainability in a broader paradigm that “takes into account the often bureaucratic and cryptic institutions that make these projects possible….”. Fellows thus studied how place-shaping sustainability projects challenge or depend upon the dominant paradigm. Related to this, most of them acknowledged a certain discomfort with the concept of sustainability as it is often used without specifying what it means or what normative and political intentions are behind it. The approach taken in these projects resembles what Loorbach, Frantzeskaki and Avelino (2017) refer to as the ‘social-institutional approach’ which renders sustainability transitions as inherently political as they imply systemic change. Linked to this approach, research projects drew attention to socio-political transitions themselves, such as the transition in democracy and from centralized governance structures to decentralized, not-for-profit, community based and/or third sector-based energy cooperatives (ibid).

Regenerative approach

A focus on regenerative development allowed fellows to go beyond the critical stance and aim at designing regenerative research processes as was done in four of the SUSPLACE projects. Regeneration understands sustainability as a continuous (place-based) process founded on a co-evolutionary partnership between ecological and socio-cultural systems (Cole et al. 2013). This includes an interest in interpretations of place as interpersonal and cultural, and argues that a shift in mindsets and in the human consciousness, and thereby also in the relations between humans and non-humans, is needed for regenerative actions. This type of research aims to understand how to “shape” places aligned with ethics and values that emerge from an ecological consciousness: “I look at imaginative leadership as a key capacity for the transformation of social ecological systems (‘place-shaping’) towards a model in which humans and natural systems work in partnership to increase the ability of natural systems to thrive (framed as ‘beyond sustainability’ or ‘regenerative development’)”. This approach to research is manifested in, for example, prioritizing the analysis of the role of leaders of social enterprises, social movements or other place-shaping initiatives. The aim of this is to reflect on participants views on sustainability and explore their values, goals, and (regenerative) practices.

Sustainability as context-dependent construct

Some fellows understand sustainability as constructed and defined by actors in places (e.g. Miller 2013). This proposition sees sustainability as negotiated in places emphasizing that sustainability inherently acknowledges spatial variety in material and immaterial contexts on multiple geographical scales: “It is a process, more than an essence or a specific goal: an emergent property in a collective discussion about desired futures”. Ideas, wishes, demands and opinions differ between actors involved and should be respected: “Basically, this means recognising sustainability as a context-dependent construct that needs to be co-defined by the actors involved”. This type of position is evidenced in research approaches prioritizing the inclusion of different viewpoints with regard to the construction of collective narratives about desired futures, rendering all voices equal.

Systemic perspective

Overall, fellows hold a systemic perspective on sustainability, highlighting the different “pillars” of sustainability, including the social, political-economic and ecological dimensions, as well as the interconnections between scales. In the course of the project, some added new dimensions: “aesthetic, inner dimension, cultural dimension”. Others criticized the three-pillar definition of sustainability because it favors one pillar (economy) over the others (ecological and social). Many fellows prioritized the inner and personal sphere of transformation including meanings, values, culture and worldviews, arguing that these are foundational conditions for the transformation of any of the other dimensions of sustainability. To support this claim they applied theories from environmental psychology, cultural geography, transformative learning and pedagogical theories (e.g. O’Brien 2013; Horlings 2015a, b; Dessein et al. 2015; Hedlund de Witt 2013). Their research was informed by concepts such as sense of place (#3), affect (#4), worldviews (#2), values (#8), learning (#14), consciousness (#2, #9), and people’s mindsets (#9).

Standing upon an explicit normative position, all fellows acknowledged knowledge brokering (between civic societies, scientists, policy makers, etc.) as part of their daily actions, particularly during the data collection phase. For example, the phase of data collection (interviews, focus groups) is useful for mediating different perspectives (#10) and key for shaping policy agendas towards a place-based development (#13), as well as for affecting current legal schemes (#4, #5), or promoting new ways of land-use (permaculture) (#7).

Research methods

Most of the methods used in SUSPLACE are qualitative, excepting the circular economy project (#10) which included a quantitative model of nutrients and waste flows. Methods are attentive to reciprocity: that is, beyond data gathering, methods provided participants with valuable experiences, moments or tools for reflection. Some of the fellows called their approach participatory action research, emphasizing interaction and fostering inclusiveness, transparency and advocacy. Another common thread was the experimentation with non-conventional methods of research, including art-based and visual methods. Among all the methods used by fellows a distinction can be made between methods for reflection, those for giving voice, and those for stimulating co-production (Quinn and De Vrieze 2019).

Methods for reflection included the more conventional qualitative methods such as reflective journals, participant observation, semi-structured interviews and focus groups, often coupled with different forms of conceptual maps and visual methods to enhance deep reflection and assure reciprocity. Participant observation was used to understand and feel the practices studied, as indicated by one of the fellows: “I both observed and participated in the linen practices…[this] allowed me to deeply understand but also endure the practices related to linen production.” This method allowed for grasping the “visceral experience,'' emotional and felt experience of the researched practice, for establishing trust “to receive honest and reflective viewpoints”, and for gleaning the “situated knowledge” necessary for “understanding comments and insights expressed by participants”. Participant observation was combined with interviews or focus groups to co-reflect the insights obtained and validate observations and assure the reciprocity of the process.

Conceptual maps were usually used for semi-structured interviews- e.g. with timelines to trace the most important events and practices of research initiatives, or with maps to draft the network of actors and institutions allowing practices as was shown in three of the projects. Concept maps provided time and space for reflection to interviewees, assuring the quality of information and the element of reciprocity. Alternatively, other support useful for reflection is silent mapping (see Pearson et al. 2018) used in the context of mapping values attached to a Finnish town (#3), and photo elicitation used for focus groups analysing food procurement (#1).

Via reflection and interaction, these methods changed both research participants and researcher, even involuntarily, as is shown in the following comment: “During the interactions with my participants, I realized that simply by having these conversations, I was making them open their minds to many issues and reflect on any internal conflicts they may have been having […] giving them the motivation […] to make positive changes.[…] it changed me as a researcher and as a person. It made me realise the gravity of the situation and the work that will be required to solve it. It, therefore, makes me more likely to enact change in my future career”.

Methods for giving voice included different forms of cartography, photovoice, collaborative video making and storytelling. These methods are grouped together because they allow giving voice to vulnerable groups whose opinions are often not heard, and to non-humans’ agency that is often ignored. Photo-voice was used with people with mental disabilities to understand green care practices through the end users’ experiences (#13), with youth to make visible their issues and stakes within a capital-region (#14), as well as with food consumers in Wales (#1). When shared with participants or exhibited publicly, photovoice allowed “understand[ing] those whose verbal communication is different” and “giv[ing] credibility to groups that are often perceived as possibly less worth listening to”. Collaborative video making was used with inhabitants of marginalized areas in the rural areas in Wales and Portugal to “show communities they can have a voice and that they have power over their territory” and to “preserve their stories as intangible heritage”. Two projects implemented cartography participatory methods. Project #14 involved young people in decision-making in Wales via a digital map platform to identify places and issues affecting them in their own city-region. Project #4 on managing the commons implemented affective cartography (i.e. Rolnik 2009) which collects stories of sentimental locations for people as a way to “make visible how the nature around them affected their lives as persons and as a way to build community and nature relations”. Finally, a group of six fellows (#4, 5, 9, 10, 13 and 14) developed fictional stories to communicate their research to a wide audience. The collection of fictional stories brings to life sustainability values and regenerative practices to empower, motivate and inform action; it also assures reciprocity with research participants and with non-humans, as it gives voice to their stories and practices.

Finally, methods to co-produce involved workshops based on several theories and methods seeking to produce something collectively, whether this is a vision for the future or a plan for a next round of actions. Most fellows used Theory U as the theory structuring their workshops (e.g. Scharmer and Kaufer 2013). Theory U provides a four-stage structure that allows people to connect to their deep values before proceeding with the next phase of designing or acting. Three fellows were also inspired by Appreciative Inquiry, which brings to the forefront the strengths and values of communities to think of ways to mobilize them (e.g. Ashford and Patkar 2001). These theories are used together with workshop exercises based on artistic experiences, as collages, maquettes, poem writing, storytelling, etc., aiming to provide non-conventional experiences to participants that can spark new framings and perspectives around an issue. As a result of this, a group of fellows (#2, #3, #9, #13) developed a toolkit of creative and art-based methods (Pearson et al. 2018). The above shows that process-impacts are prioritized focusing more on the collective learning process than on the outcomes.

Discussion

Reflections on the roles of researchers

By using the typology of Wittmayer and Schäpke on roles of researchers as an inspiration we have explored the various roles of the fellows in the 15 projects of the SUSPLACE-program. Overall, our study confirms the presence of the five roles of researchers suggested by Wittmayer and Schäpke (2014) within sustainable research: the reflective scientist, process facilitator, knowledge broker, change agent and self-reflexive scientist. The results showed that researchers do not see these roles as separate or as a single choice to be made, which is in line with the observations by Wittmayer and Schäpke (2014, 492): different roles were taken up in different phases of the research and sometimes multiple roles were combined, for example a role as facilitator and as a change agent. The roles taken by fellows depend on their personal capabilities and networks when conducting their research as well as on their normative positioning towards sustainability and research, and the process of engagement with different theories and with the place. We discuss here how each role described by Wittmayer and Schäpke (2014) play out in the context of place-based sustainability research.

With regard to the role of a reflective scientist, a notion of the objective researcher is sometimes used, for example in physical sciences, analyzing empirical phenomena from a distant, unengaged perspective. We challenge the idea of the ‘neutral’ researcher, aiming ‘ to get the facts right’, without questioning personal values and biases that might influence the outcomes (see also Mertens 2012; Fazey et al. 2018). Instead, a reflective role involves being mindful of biases, values and personal motivations that colour the perspective of the researcher. In SUSPLACE the self-reflective role of fellows resulted in a greater self-awareness and active choices around normative commitments, sustainability and methods applied. For example, by creating relations of trust they aimed to open meaningful dialogues, to establish personal bonds which enabled situated knowledge.

Self-reflection on their own as well as others' normative commitments and values, enabled some fellows to take on a more effective role as a knowledge broker, acknowledging the particular constellation of people’s voices, interests, knowledges and objectives in place-based research, and aiming to incorporate this diversity in their research. Fellows also contributed to knowledge brokering by disseminating their insights to different groups, for example by writing about results in the form of children’s stories.

As a result of increased awareness some of the fellows took on a role as process facilitator or engage as change agents. They acquired ‘response-ability’, obtaining the necessary skills and building networks to play such roles, but also became more critical during their engagement in places toward theoretical notions of sustainability. For example, some fellows chose a more activist (Jhagroe 2018) or regenerative perspective on place-shaping, which informed their theoretical positioning, as well as their choice of methods. In a facilitator role, they supported reflections of participants on their place by applying creative and visual methods.

The capacity of fellows to discuss their own positionality and normativity confirms with the role of the self-reflexive scientist, described by Wittmayer and Schäpke (2014), as some fellows found that the experience of personal transformation and awareness may be a precondition for facilitating transformative processes. As fellows became part of the relations that shape a place, they also, whether deliberately or not, contributed to place-shaping, either by giving their perspective on certain practices or by actively engaging or facilitating planning, envisioning or reflection processes.

Some took the notion of the self-reflexive scientist a step further. They argued that in seeing themselves as part of dynamic actions, researchers bring in their ‘whole self’: their personal background, values, skills, attitudes and ambitions when engaging in places and with people. Being self-reflexive then also involves reflecting upon the researcher’s own responsibility and willingness to change themselves as a result of what the researcher learnt from doing the research. Furthermore, integrating lessons learnt in one’s own life and work environment creates another space of possible transformation. The research itself then becomes an experimental space for implementing sustainability values and learnings, and for practicing transformation.

Following this argument, we define transformative methods not only as those producing transformational change but also those that transform the way research is being conducted, for example centering the research process around themes such as inclusivity, reciprocity, esthetics, vulnerability and trust. An example of this can be found at Moser (2016) who shows how the co-design of research brings forward ethics and equity debates to the fore of the research design, which is, by itself transformative, as it challenges pre-existing knowledge systems. While an in-depth exploration of this issue is beyond the scope of this paper, we suggest this as an interesting avenue for future research.

Our findings underpin the relevance for researchers to position themselves explicitly in theoretical debates, explicating how the concept of ‘sustainability’ is linked to normative and political intentions and assumptions (Wuesler 2014). Overall, our results confirm the importance of the pluralisation of research (Blythe et al. 2018) as a mechanism to safeguard against the appropriation of the term by any single framing or perspective. In this respect, the research projects show a shift from descriptive–analytical notions of sustainability towards more process-oriented approaches in sustainability research, in line with Miller (2014).

The embodied researcher

Based on our analysis we propose a new conceptualisation of the role of researchers in the context of place-based sustainability research: the embodied researcher. Figure 1 represents this role as composed of four elements of the body: head, heart, hands and feet. By using the visual representation of the body, we show that in the context of place-based research researchers 'suspend' the categorization of different roles. We portray the researcher in all their 'wholeness' and explain the manner in which they carry out research through their place engagement, normative assumptions towards sustainability, theoretical positioning and methodological choices. Moreover, we consider “reflection” and “reflexivity” not as separate roles, but as something that is present throughout the research process affecting the four dimensions of the body of the researcher.

An embodied researcher ideally practices research informed by the heart. All fellows started with a wish to support change towards sustainability, which can be understood as an inner compass, and is represented here as the heart. These visions of sustainability and research positionality profoundly shaped how research is practiced. Their vision, wishes, commitment and responsibilities in relation to sustainability in some cases changed throughout the research, via a process of self-questioning, sense-making and self-transformation after confronting themselves with theoretical concepts (brain). For example, the meaning of sustainability shifted when reflecting upon the role of research and the ‘how’ of doing research, as well as through the experiences fellows had by their engagement with places.

The way fellows conceptualised and engaged with places and participants is represented in the feet component (Fig. 1). The feet illustrate the embodied engagement in places: doing research as “human beings” who hold specific normative positions, develop personal connections and ethical responsibilities towards the places and communities they research and reflect upon their own position within the networks of relations that constitute a place. Engagement as a “human being” emphasizes the importance of paying attention to the inner processes of learning and change as a result of engagement in places.

This learning and change connect the feet to the other three components. Engagement in places (feet) is done through experimentation with varied methods and actions and via developing response-ability (hands), which is rooted in and shapes the researcher’s normative positions (heart). The hands came forward as an important aspect of research as fellows consider the “how” research is done often more important than the outcome, reflecting a process-based approach. Once immersed in places and networks and self-aware of their own wishes, skills and capacities, researchers engage “their hands” acting as knowledge brokers, process facilitators, or change agents. Some engaged in the ethical and political planning of actions developing action research projects (e.g. video making, co-production workshops, etc.) grounded on values such as inclusivity, equality and justice. Others took a policy sensitive role intervening with planners and policy-makers in place-shaping processes. In this case, they acted as knowledge brokers while considering their own normative positionality.

From the hands and heart, we finally arrive at the head (the brain) representing how researchers theoretically made sense of all they have experienced (their learning and doing). This includes the manner in which they used interviews, focus groups and other more cognitive-based research methods. It also involves the way they acted as knowledge brokers and supported their values and visions (heart) through using particular theories and methods, possibly challenging certain types of hegemonic knowledge, framing their research questions and focusing on specific practices; all of which demands a continuous process of self-reflection. Self-transformation in place-based research is a process that happens through our embodied experience in places; as such it happens in the realm of the feet (Fig. 1). Yet, this paper finds that all four components of the body of the researcher play a role in self-transformation. Self-transformation happens by engaging with critical theories related to sustainability and transformations (head), by reflecting upon one’s own normative position as a researcher (heart), by experimenting with methods grounded on one’s own values (hands) and by engaging in places as a human being open to developing response-ability (feet).

While we don’t equate self-transformation with sustainability science in general, the paper claims that in the context of place-based research it can be a legitimate outcome of research. As such, we define place-based research as a particular type of sustainability research in which researchers take a critical and explicitly normative standpoint in relation to sustainability, engage in the research as an embodied researcher and value process-based outcomes.

Figure 1 shows what is meant by embodied research practice and its relation to self-transformation and sustainability.

Conclusion

This paper contributes to the debate on place-based sustainability research by reflecting upon the roles of the researcher. For this purpose, we explored and analyzed the research of 15 fellows working on the joint framework of sustainable place-shaping within the SUSPLACE program.

We consider place-based research as a particular type of sustainability research, not yet analyzed in terms of research roles. The study confirmed the existence of the varied roles of researchers as identified by Wittmayer and Schäpke (2014) showing that—in the context of place-based research, researchers 'suspend' the categorization of different roles, combining and changing roles over time.

The SUSPLACE program started with the idea that by engaging with diverse actors, place-based research could result in the development of new networks, narratives, and arrangements, which can alter the multi-scale material and immaterial relations that make up places, and potentially render these more sustainable (Roep et al. 2015; Horlings et al. 2019). Although this might be true for many of the research projects analyzed, our findings also emphasized the transformative effect of the way researchers engage in places and practice their methods. Our results suggest that self-reflexivity can result in self-transformation, witnessed through the process-impacts on participants and on the researcher.

Following this line, we have summarized the role of researchers in place-based research as ‘embodied’. Embodied research is seen as a transformative practice in itself as it is rooted in sustainability practices and values (e.g. reciprocity, inclusivity, transparency, care, etc.).

Our characterization of the role of place-based sustainability researchers brings forward important questions on sustainability science. Acknowledging the importance and legitimacy of embodied researchers means that research is being recognized research as a vehicle for empowerment and self-transformation. In other words, research can be a practice that supports political subjects acting upon the sustainability and transformation of our planet. This type of research might be in conflict with dominant academic practice, as it redefines questions of impact and objectivity, and may entail activities beyond written scientific outputs. Thus, there is a need to develop new metrics of academic social impact grounded on the transformational premises of embodied researchers. We hope this paper helps to legitimate and further develop this type of research.

References

Alvesson M, Sköldberg K (2011) Reflexive methodology. New vistas for qualitative research, 2nd edn. Sage, Thousands Oaks

Ashford G, Patkar S (2001) Using appreciative inquiry in rural Indian communities. International Institute for Sustainable Development, Winnipeg

Axinte LF, Mehmood A, Marsden T, Roep D (2019) Regenerative city-regions: a new conceptual framework. Reg Stud 6(1):117–129. https://doi.org/10.1080/21681376.2019.1584542

Barca F (2009) An agenda for reformed cohesion policy: a place-based approach to meeting European Union challenges and expectations. Independent report prepared at the request of D. Hübner, Commissioner for Regional Policy, Brussels

Barca F, McCann P, Rodriguez-Pose A (2012) The case for regional development intervention: place-based versus place-neutral approaches. J Reg Sci 52(1):134–152

Bartel KPR, Wittmayer JM (2014) Symposium introduction: usable knowledge in practice. What action research has to offer to critical policy studies. Crit Policy Stud 8(4):397–406

Berkes F, Colding J, Folke C (2003) Navigating social-ecological systems: building resilience for complexity and change. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Bernal DD (1998) Using a Chicana feminist epistemology in educational research. Harvard Educ Rev 68(4):555–583

Blythe J, Silver J, Evans L, Armitage D, Bennett NJ, Moore ML, Morrison TH, Brown K (2018) The dark side of transformation; latent risks in contemporary sustainability discourse. Antipode 50(5):1206–1233

Bradbury-Huang H (2015) The SAGE handbook of action research. Sage, Thousand Oaks

Brayboy B (2000) The Indian and the researcher: tales from the field. Int J Qual Stud Educ 13(4):415–426

Braud W, Anderson R (1998) Transpersonal research methods for the social sciences: honoring human experience. Sage, Thousands Oaks

Campbell and Vanderhoven (2016) Knowledge that matters: realising the potential of co-production. Final Report N8/ESRC Research Programme. N8Research Partnership, Manchester

Carew AL, Wickson F (2010) The TD wheel: a heuristic to shape, support and evaluate transdisciplinary research. Futures 42(10):1146–1155. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.futures.2010.04.025

Chaudhry LN (2000) Researching "my people," researching myself: fragments of a reflexive usle. In: St. Pierre E, Pillow W (eds) Working the ruins: feminist poststructural research and practice in education. Routledge, New York, pp 96–113

Clough PT (1992) The end(s) of ethnography: from realism to social criticism. Sage, Newbury Park

Cole RJ, Oliver A, Robinson J (2013) Regenerative design, socio-ecological systems and co-evolution. Build Res Inf 41:237–247. https://doi.org/10.1080/09613218.2013.747130

Dentoni D, Waddell S, Waddock S (2017) Pathways of transformation in global food and agricultural systems: Implications from a large systems. Curr Opin Environ Sustain 29:8–13

Dessein J, Battaglini E, Horlings L (eds) (2015) Cultural sustainability and regional development; theories and practices of territorialisation. Routledge, London

Etzkowitz H, Leydesdorff L (2000) The dynamics of innovation: from National Systems and ‘‘Mode 2’’ to a Triple Helix of university–industry–government relations. Res Policy 29:109–123

Fazey I, Schäpke N, Caniglia G, Patterson J et al (2018) Ten essentials for action-oriented and second order energy transitions, transformations and climate change research. Energy Res Soc Sci 40:54–70

Feola G (2015) Societal transformation in response to global environmental change: a review of emerging concepts. Ambio 44(5):376–390

Frank A (2017) What is the story with sustainability? A narrative analysis of diverse and contested understandings. J Environ Stud Sci 7:310–323

Franklin A, Marsden TK (2014) (Dis)connected communities and sustainable placemaking. Local Environ Int J Justice Sustain 20(8):940–956

Folke C, Hahn T, Olsson P, Norberg J (2005) Adaptive governance of social-ecological systems. Annu Rev Environ Resour 30:441–475

Fonow MM, Cook J (1991) Back to the future: a look at the second wave of feminist epistemology and methodology. In: Fonow MM, Cook J (eds) Beyond mnet hodolщrj: feminist schohrship as lived research. Indiana University Press, Bloomington, pp 1–15

Giddens A (1994) The constitution of society: outline of the theory of structuration. Polity, Cambridge

Geels FW, Schot J (2007) Typology of sociotechnical transition pathways. Res Policy 36(3):399–417

Geels FW (2014) Regime resistance against low-carbon transitions: introducing politics and power into the multi-level perspective. Theory Cult Soc 31(5):21–40

Geels FW, Sovacool BK, Schwanen T, Sorrell S (2017) Sociotechnical transitions for deep decarbonization. Science 357(6357):1242–1244

Grenni S, Soini K, Horlings LG (2019) The inner dimension of sustainability transformation: how sense of place and values can support sustainable place-shaping. Sustain Sci. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-019-00743-3

Haraway D (2010) When species meet: staying with the trouble, environment and planning D: society and space. Sage, London. https://doi.org/10.1068/d2706wsh

Healey P, de Magalhaes C, Madanipour A, Pendlebury J (2003) Places, identity and local politics: analyzing initiatives in deliberative governance. In: Hajer M, Wagenaar H (eds) Deliberative policy analysis Understanding governance in the network society. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp 60–86

Hedlund-de Witt A (2013) Worldviews and their significance for the global sustainable development debate. Environ Ethics 35:133–162

Heley J, Jones L (2012) Relational rurals: some thoughts on relating things and theory in rural studies. J Rural Stud 28(3):208–217. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2012.01.011

Hes D, Du Plessis C (2014) Designing for hope; pathways to regenerative sustainability. Routledge, London

Hilger A, Rose M, Wanner M (2018) Changing faces—factors influencing the roles of researchers in real-world laboratories. GAIA Ecol Perspect Sci Soc 27(1):138–145

Horlings LG (2015a) Values in place: a value-oriented approach toward sustainable place-shaping. Reg Stud 2(1):256–273

Horlings LG (2015) The inner dimension of sustainability. Curr Opin Environ Sustain 14:163–169. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cosust.2015.06.006

Horlings LG (2016) Connecting people to place: sustainable place-shaping practices as transformative power. Curr Opin Environ Sustain 20:32–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cosust.2016.05.003

Horlings LG (2017) Transformative planning; enabling resourceful communities. Online, https://www.InPlanning.eu. Accessed 18 Jan 2019

Horlings LG (2018) Politics of connectivity: the relevance of place-based approaches to support sustainable development and the governance of nature and landscape. In: Marsden T (ed) Handbook nature. Sage, London, pp 304–324

Horlings LG (ed) (2019) Sustainable place-shaping: what, why and how. Findings of the SUSPLACE program; Deliverable D7.6 Synthesis report. Wageningen University and Research, Wageningen. https://www.sustainableplaceshaping.net. Accessed 28 Oct 2019

Husain O, Franklin A, Roep D (2019) Decentralising geographies of political action: civic tech and place-based municipalism. J Peer Prod 13:1–22

IISC (2019) International Social Science Council: https://www.worldsocialscience.org/. Accessed on 18 Jan 2019

Jhagroe S (2018) Transition scientivism: on activist gardening and co-producing transition knowledge ‘from below’. In: Bartels KPR, Wittmayer JM (eds) Action research in policy analysis Critical and relational approaches to sustainability transitions, chapter 4. Routledge, London

Johnson-Bailey J (1999) The ties that bind and the shackles that separate: race, gender, class, and color in a research process. Qual Stud Educ 12(6):659–670

Lang DJ, Wiek A, Bergmann M, Stauffacher M, Martens P, Moll P, Swilling M, Thomas CJ (2012) Transdisciplinary research in sustainability science: practice, principles, and challenges. Sustain Sci 7(S1):25–43

Latour B (2004) How to talk about the Body? The normative dimension of science studies. Body Soc 10:205–229. https://doi.org/10.1177/1357034X04042943

Leach M, Rockstrom J, Raskin P, Scoones I, Stirling AC, Smith A, Thompson J, Millstone E, Ely A, Arond E, Folke C, Olsson P (2012) Transforming innovation for sustainability. Ecol Soc 17(2):11. https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-04933-170211

Loorbach D (2010) Transition management for sustainable development: a prescriptive, complexity-based governance framework. Governance 23(1):161–183

Loorbach D, Frantzeskaki N, Avelino F (2017) Sustainability transitions research: transforming science and practice for societal change. Annu Rev Environ Resour 42:599–626

Luederitz C, Schäpke N, Wiek A, Lang DJ, Bergmann M, Bos JJ, Burch S, Davies A, Evans J, König A, Farrelly MA, Forrest N, Frantzeskaki N, Gibson RB, Kay B, Loorbach D, McCormick K, Parodi O, Rauschmayer F, Schneidewind U et al (2017) Learning through evaluation—a tentative evaluative scheme for sustainability transition experiments. J Clean Prod 169:71–76

Lumsden K (2019) Reflexivity. Theory, method and practice, 01–03, 1st edn. Routledge, London, p 192

Lyle JT (1994) Regenerative design for sustainable development. Wiley, Oxford

MacCallumn D, Moulaert F, Hiller J, Haddock SV (2009) Social innovation and territorial development. Routledge, London

Mang P, Reed B (2013) Regenerative development and design. In: Loftness V, Haase D (eds) Sustainable built environments. Springer, New York, pp 478–501

Marsden T (2012) Sustainable place-making for sustainability science: the contested case of agri-food and urban–rural relations. Sustain Sci 8(2):213–226

Marsden T, Bristow G (2000) Progressing integrated rural development: a framework for assessing the integrative potential of sectoral policies. Reg Stud 34(5):455–469

Massey D (1991) A global sense of place. Marx Today 1991:24–29

Massey D (2004) Geographies of responsibility. Geografiska Ann 86B(1):5–18

Massey D (2005) For space. Sage, London

Mauser W, Klepper G, Rice M, Schmalzbauer BS, Hackmann H, Leemans R, Moore H (2013) Transdisciplinary global change research: the co-creation of knowledge for sustainability. Curr Opin Environ Sustain 5(3–4):420–431

Mertens DM (2012) Transformative mixed methods. Addressing inequities. Am Behav Sci 56:802–813. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764211433797

McGowan KA, Westley F, Fraser EDG, Loring PA, Weathers KC, Avelino F, Sendzimir J, Chowdhury RR et al (2014) The research journey: travels across the idiomatic and axiomatic toward a better understanding of complexity. Ecol Soc 19(3):27. https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-06518-190337

Miah JH, Griffiths A, McNeillI R, Poonaji I, Martin R, Morse S, Yang A, Sadhukhan J (2015) A small-scale transdisciplinary process to maximising the energy efficiency of food factories: insights and recommendations from the development of a novel heat integration framework. Sustain Sci 10(4):621–637

Miller TR (2013) Constructing sustainability science: emerging perspectives and research trajectories. Sustain Sci 8:279. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-012-0180-6

Miller TR, Wiek A, Sarewitz D (2014) The future of sustainability science: a solutions-oriented research agenda. Sustain Sci 9:239. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-013-0224-6

Mollison B, Holmgren D (1978) Permaculture one. Tagari, Australia

Moriggi A (2019) Exploring enabling resources for place-based social entrepreneurship: a participatory study of Green Care practices in Finland. Sustain Sci. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-019-00738-0

Moriggi A, Soini K, Franklin A, Roep D (forthcoming) A care-based approach to transformative change: ethically-informed practices, relational response-ability & emotional awareness

Moser SC (2016) Can science on transformation transform science? Lessons from co-design. Curr Opin Environ Sustain 20:106–115. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cosust.2016.10.007

Motzafi-Haller P (1997) Writing birthright: On native anthropologists and the politics of representation. In: Reed-Danahay DE (ed) Auto/ethnography: rewriting the self and the social. Berg, New York, pp 95–222

Murdoch J (2000) Networks—A new paradigm of rural development? J Rural Stud 16(4):407–419. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0743-0167(00)00022-X

Newman M (2014) Transformative learning. Adult Educ Q 64(4):345–355

Nieto-Romero M, Valente S, Figueiredo E, Parra C (2019) Historical commons as sites of transformation. A critical research agenda to study human and more-than-human communities. Geoforum. Elsevier, Oxford. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2019.10.004

Oakley A (1981) Interviewing women: a contradiction in terms? In: Roberts II (ed) Doing feminist research. Roudledge, New York, pp 30–61

O’Brien K (2012) Global environmental change II: From adaptation to deliberate transformation. Progress Hum Geogr 36(5):667–676

O’Brien K (2013) The courage to change: adaptation from the inside out. In: Moser SC, Boykoff MT (eds) Successful adaptation to climate change: linking science and policy in a rapidly changing world. Routledge, Abingdon, pp 306–3019

Olsson P, Galaz V, Boonstra WJ (2014) Sustainability transformations: a resilience perspective. Ecol Soc 19(4):1. https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-06799-190401

Pearson KR, Backman M, Grenni S, Moriggi PS, de Vrieze A (2018) Arts-based methods for transformative engagement: a toolkit. SUSPLACE, Wageningen. https://doi.org/10.1817/441523

Pelling M, O’Brien MD (2015) Adaptation and transformation. Clim Change 133(1):113–127. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-014-1303-0

Pierce J, Martin DG, Murphy JT (2011) Relational place-making: the networked politics of place. Trans Inst Br Geogr 36:54–70

Pillow W (2003) Confession, catharsis, or cure? Rethinking the uses of reflexivity as methodological power in qualitative research. Int J Qual Stud Educ 16(2):175–196

Pisters SR, Vihinen H, Figueiredo E (2019) Place based transformative learning: a framework to explore consciousness in sustainability initiatives. Emot Space Soc 32:100578. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emospa.2019.04.007

Pohl C, Rist S, Zimmermann A, Fry P, Gurung GS, Schneider F, Speranza CI, Kiteme B, Boillat S, Serrano E, Hadorn GH, Urs W (2010) Researchers’ roles in knowledge co-production: Experience from sustainability research in Kenya, Switzerland, Bolivia and Nepal. Sci Public Policy 37:267–281. https://doi.org/10.3152/030234210X496628