Abstract

Boron oxide is frequently applied in modification of stainless steelmaking slag to mitigate the disintegration of slag. In this work, the effect of B2O3 on mineralogical phases and hexavalent chromium leaching behavior of synthetic CaO–SiO2–MgO–Al2O3–CrOx slag was investigated. Di-calcium silicate, merwinite, spinel, akermanite, and matrix phase were observed as main minerals in slags by scanning electron microscope (SEM) equipped with energy-dispersive spectrometry (EDS) and X-ray diffraction (XRD) techniques. It was found that 2% B2O3 addition is sufficient to eliminate the disintegration of synthetic slag by suppressing the phase transition to γ-Ca2SiO4. The size of spinel phase increases with increasing B2O3, which could be well interpreted by enhanced Ostwald ripening. The amount of Ca2SiO4 phase in slag was reduced by addition of B2O3; however, excess B2O3 (> 2%) addition would significantly increase chromium concentration and overall chromium distribution in Ca2SiO4 phase. Leaching results according to US-EPA-3060A method indicated that excess boron oxide addition (> 2%) leads to a significant increase of hexavalent chromium leaching concentrations and should be avoided for stabilizing stainless steel slag.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Stainless steel slag is generated in the production of stainless steel. Generally, stainless steel slag consists of CaO, SiO2, MgO, and some amount of Cr2O3 (< 10%) that originates from the oxidation of chromium during alloying process. The valence state of chromium in stainless steel slag is mainly divalent (Cr2+) or trivalent (Cr3+) that has low toxicity. Unfortunately, low valent chromium could be oxidized into highly toxic hexavalent chromium (Cr6+) when exposed to acidic and oxygen-rich environments [1]. Hexavalent chromium is water-soluble and easy to be leached into underground water to produce serious environmental pollution. Moreover, disintegration behavior is commonly observed in stainless steel slag during natural cooling [2], which is generally caused by the phase transition from β-Ca2SiO4 to γ-Ca2SiO4 accompanied by 12% volume expansion [3]. The leaching of hazardous hexavalent chromium could also be aggravated by the disintegration behavior. Therefore, the utilization of stainless steel slag is still limited.

To suppress the disintegration behavior and immobilize the chromium in slag, many stabilization techniques for slag have been proposed. The mitigation of disintegration of slag could be achieved by some physical methods, such as rapid cooling to suppress the phase transition [3]. The modification of slag could be performed by additives to mitigate the disintegration of slag and immobilize chromium in slag [4,5,6,7,8,9]. It is well accepted that spinel phase is very stable during oxidation and leaching due to the strong bonding of chromium in spinel phase [2]. Modification with MgO could mitigate the precipitation of Ca2SiO4 [4] and be beneficial to spinel formation during solidification of slag [5, 6]. The additions of appropriate amounts of Al2O3 [5, 7], MnO [8], and FeO [9] were found to promote the spinel formation. Meanwhile, low basicity [6, 8, 10] and oxygen partial pressure [11] have a positive influence on spinel precipitation.

Boron oxide has been found to be an excellent stabilizer for stainless steel slag [12,13,14,15,16]. Ghose et al. concluded that 0.13 wt% B2O3 can already stabilize the β-polymorph of Ca2SiO4 [12]. Seki et al. developed a borate-based stabilizer for stainless steel decarburisation slag [13]. Durinck et al. considered that the crystallographic mechanism could be the partial replacement of SiO44− units by BO33− units that suppresses the Ca2+ migrations and SiO44− rotations required for the β-Ca2SiO4 to γ-Ca2SiO4 transformation [14]. Wu et al. studied the influence of B2O3 on crystallization behavior of Cr-bearing phase in stainless steel slag [15]. They found that the size of Cr-bearing phase in slag with B2O3 enhanced as an increase of holding time and the content of Cr2O3 in the spinel phase was higher than that in the slag without B2O3 [15]. Based on the fact that boron can stabilize stainless steel slag effectively, boron-contained materials have been applied for the stabilization of stainless steel slag in some steel companies [13, 16]. The boron-contained materials are usually added into molten stainless steel slag during the slag discharge process. However, the effect of boron oxide addition on leaching behavior of hexavalent chromium in treated stainless steel slag received only a few investigations. Recently, Li and Xue investigated the effect of boron oxide addition on the chromium distribution in Cr-bearing phase and emission of hexavalent chromium [17]. They reported that the leachability of hexavalent chromium was enhanced with increasing of boron oxide content in some cases [17]. Unfortunately, the detailed mechanism for that was not discussed in their work. Accordingly, the effects of B2O3 on mineralogical phases and chromium leaching of slags still require further studies.

In the present work, the effect of B2O3 addition on the phase formations in synthetic CaO–SiO2–MgO–Al2O3–CrOx slag was investigated under a low oxygen partial pressure (PO2 = 10−10 atm). The chromium distributions in different mineralogical phases were quantified. Furthermore, the leaching concentrations of hexavalent chromium were also evaluated according to US-EPA-3060A method [18].

Materials and methods

Reagent-grade compounds CaO, SiO2, Al2O3, MgO, Cr2O3, and H3BO3 were taken as raw materials. The chemical compositions of the samples investigated are listed in Table 1. Reagent-grade CaCO3 was calcined at 1373 K overnight in muffle furnace to obtain CaO. To avoid the occurrence of hydroxide and carbonate, MgO was also calcined at 1273 K for 6 h in muffle furnace. SiO2, Al2O3, and Cr2O3 were dried at 393 K for 4 h in an oven to remove moistures. H3BO3 as a substitute of B2O3 was added directly without drying in the present work for the reason of its low melting point (449 K) [19]. The basicity of synthetic slag (defined as the mass ratio of CaO to SiO2) was maintained as 1.5, considering that the basicity of industrial stainless steel slag is generally in the range of 1.0 ~ 2.5 [5,6,7,8,9,10,11]. The contents of MgO, Al2O3, and Cr2O3 in slags were fixed as 8.0, 6.0, and 6.0, respectively. The reagent powders were mixed with appropriate ratios and pressed into pellets. The pellets were loaded in molybdenum crucibles, and then located in the even temperature zone of a tube furnace with molybdenum silicide as heating elements using molybdenum wire. Schematic diagram of the furnace can be found in our previous publication [20]. A W-Re5/26 thermocouple was installed underneath the bottom of molybdenum crucible to measure and control the temperature within the furnace. Oxygen partial pressure of 10–10 atm was maintained by mixing gas of CO and CO2 (CO/CO2 = 41). The flow rate of gases was controlled by two mass flow meters (Bronkhorst EL-FLOW Base). Samples were heated to 1873 K slowly followed by cooling to room temperature with a rate of 5 K·min−1.

After cooling, the mineralogical phases in samples were investigated using scanning electron microscopy equipped with energy-dispersive spectra (SEM–EDS) and X-ray diffraction (XRD). For SEM examination, samples were embedded with epoxy resin and prepared by standard metallographic preparation methods. The SEM examination was performed on FEI MLA 250. The working voltage was 20 kV.

The XRD spectra were collected with an 18 kW X-ray diffractometer (model: Rigaku TTR III, Japan) with Cu–Ka radiation. The 2θ scanning range was 15°–65° with a scan speed of 2 s step−1. The mass percentages of various crystalline phases were determined using an X-ray quantitative analysis method based on RIR (Relative Intensity Ratio) values [21], which was described briefly as follows.

The ratio of mass percentage of α phase to β phase could be calculated from intensities of the strongest peaks for α phase to β phase according to the following equation:

where ω(α) and ω(β) are mass percentages of α and β phases, respectively. RIR(α) and RIR(β) are relative intensity ratio values for α and β phases, respectively. I(α) and I(β) are intensities of the strongest peaks for α and β phases, respectively. RIR values for various phase could be found in Joint Committee on Powder Diffraction Standards-International Centre for Diffraction Data (JCPDS-ICDD) cards. Thus, mass percentages of various phases could be calculated using intensities of the strongest peaks and RIR values for various phases.

US-EPA-3060A method, an alkaline digestion step, is widely used to assess the leaching concentration of hexavalent chromium in solid waste [18]. According to the standard procedure, the alkaline digestion was carried out on 2.5 g samples in this work. The leaching agent was 50 mL alkaline solution containing 0.28 M Na2CO3 and 0.5 M NaOH. 400 mg anhydrous MgCl2 and 0.5 mL buffer solution (0.5 M K2HPO4 and 0.5 M KH2PO4) were also added into the beaker to avoid oxidation of trivalent chromium. After digesting, the suspensions were filtered by vacuum filtration process with a 0.45 μm standard filter paper. Subsequently, the chromium concentration in filtrate was detected by inductively coupled plasma-optical emission spectrometer (ICP-OES, Optima-7000DV, Perkin Elmer).

The mineralogical phases of slags determined by SEM–EDS and XRD techniques were also compared with the simulation results calculated by a commercial thermodynamic software, FactSage 7.0 (Thermfact and GTT-technologies) [22]. FToxide database and Scheil–Gulliver cooling model [23] were employed during calculation.

Results and discussion

Disintegration behavior of slags

Figure 1 shows the morphology of samples containing different B2O3 contents after cooling. The sample free of B2O3 showed very serious disintegration behavior, while other samples showed no disintegration. This indicates that only slight addition of 2% B2O3 would mitigate the disintegration of slag. It is well known that di-calcium silicate exists in five different polymorphic forms: α, α’H, α’L, β, and γ [24]. α-Ca2SiO4 is stable at high temperature and γ-Ca2SiO4 is stable at room temperature. α′-Ca2SiO4 has two different forms, α′H-Ca2SiO4 and α′L-Ca2SiO4, originating from the translocation of calcium atoms. β-Ca2SiO4 is a kind of metastable substance, which usually transforms to γ-Ca2SiO4 at 673–773 K during slow cooling. Due to the difference of density between them (ρ(β-Ca2SiO4) = 3.28 g·cm−1, ρ(γ-Ca2SiO4) = 2.97 g·cm−1) [13], the phase transition is accompanied by 12% volume expansion, which is attributed to be the main reason for slag disintegration [3]. The XRD patterns for various samples are presented in Fig. 2. γ-Ca2SiO4 which is the stable form of Ca2SiO4 at room temperature can be found in the slag free of B2O3, indicating that the sample underwent phase transition during slow cooling. By comparison, high-temperature form α′-Ca2SiO4 dominantly existed in the samples with addition of B2O3. Therefore, addition of B2O3 can effectively suppress the phase transition of Ca2SiO4 and mitigate the disintegration behavior of stainless steel slag.

Mineralogical phases in slags

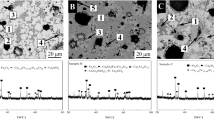

Mineralogical phases in all samples were determined by combining XRD with SEM–EDS analysis, as presented in Figs. 2 and 3, respectively. Four crystalline phases as Ca2SiO4 in light gray, merwinite in dark gray, akermanite in light black, and spinel in white were identified in SEM micrographs by EDS. Determined average chemical compositions of various phases are summarized in Table 2. The concentration of matrix in sample free of boron oxide was not determined due to its disintegration nature. The XRD patterns of samples also showed the existence of four kinds of crystalline phases. The mass percentages of crystalline phases in samples were determined by X-ray quantitative analysis and are presented in Table 3. It should be mentioned that the mass percentage of matrix cannot be determined by the method employed and it is excluded in the calculation of mass percentage of crystalline phases. It could be found from the micrographs of various samples that the matrix phases actually are very few due to the strong crystallization during cooling.

The phase precipitations of various slags during cooling were simulated by FactSage using Scheil–Gulliver model. The results are shown in Fig. 4. Spinel is the first crystalline phase during slag cooling, followed by Ca2SiO4, merwinite, and akermanite for the slags with B2O3% = 0, 2, and 4%, which is in consistence with experimental results. For the slag with B2O3% = 6%, FactSage calculation predicts that there is no precipitation of Ca2SiO4 which is contradict to the experimental results. This could be due to the kinetic factor involved in the crystallization of slags. There are some existence of spinel and Ca2SiO4 at 1873 K in FactSage calculation results, indicating that the synthetic slag should be solid–liquid coexisting slag at high temperature. The proportion of liquid phase in B2O3-free sample was about 55% at 1873 K, and increased continuously up to 95% after adding B2O3, indicating that B2O3 is beneficial to melting of slag. Some slight increase of spinel mass was found during cooling in calculation results, indicating slight precipitation of spinel during cooling. The total precipitation amount of spinel was maintained unchanged at 10% with addition of B2O3. In contrast to the experimental results, Ca3Si2O7 and CaSiO3 were found to be precipitated at low temperature for samples with 4 and 6% B2O3 addition in FactSage calculation. This inconsistency could be also due to the kinetic factors for crystallization. The calculated amount of precipitated Ca2SiO4 decreased with increasing B2O3 content for the slags with B2O3% = 0, 2, and 4%.

As seen in Fig. 2, the intensity of characteristic diffraction peak of Ca2SiO4 at 2θ = 32.6º was reduced obviously with increasing B2O3 content in slag. The mass percentage of Ca2SiO4 determined by XRD quantitative analysis (see Table 3) decreased from 33.72 to 20.42% as B2O3 content increases from 0 to 6%. The FactSage simulation results shown in Fig. 4 also indicate that the precipitated amount of Ca2SiO4 decreases as B2O3 increases from 0 to 4%. Therefore, the addition of B2O3 would suppress the crystallization of Ca2SiO4. However, the concentrations of chromium in Ca2SiO4 phase were found to be significantly increased with addition of B2O3. As listed in Table 2, in samples free of B2O3 and with 2% B2O3, there were only slight Cr2O3 content (0.73%, 0.79%) in Ca2SiO4 phase. While for samples with 4 and 6% B2O3 addition, 4.40 and 2.99% Cr2O3 were found to be in Ca2SiO4 phase, respectively. The overall amount of Cr2O3 distributed in each phase can be calculated by multiplying the mass percentage of each phase by the concentration of Cr2O3 in each phase. The calculated Cr2O3 distributions in various phases are also listed in Table 2. It could be seen that spinel phase has the largest Cr2O3 distribution, followed by di-calcium silicate phase. As shown in Fig. 5, although the mass percentage of di-calcium silicate phase decreases all the time, the Cr2O3 distribution in di-calcium silicate phase is significantly enhanced by excess addition (> 2%) of B2O3. In samples with B2O3% = 0 and 2%, the Cr2O3 distributions (0.25%, 0.19%) in di-calcium silicate phase are much lower than those in spinel phase (3.62%, 2.44%). With further B2O3 addition, the Cr2O3 distribution in di-calcium silicate phase significantly increases. In samples with B2O3% = 4 and 6%, the Cr2O3 distributions (1.02%, 0.61%) in di-calcium silicate phase could be compared with those (2.01%, 2.15%) in spinel phase. The overall amount of Cr2O3 distributed in di-calcium silicate phase is significantly increased for samples with excess B2O3 addition due to the large increase of the concentrations of chromium in Ca2SiO4 phase.

Generally, chromium has several valence states such as Cr2+, Cr3+, and Cr6+. Many factors such as composition, melting temperature, and oxygen partial pressure have some influences on the valence of chromium in slags. Pretorious [25] and Wang [26] concluded that divalent chromium predominates in the high-temperature system with low oxygen partial pressure and basicity. Due to the fact that all the samples were heated to 1873 K in low oxygen partial pressure atmosphere (10–10 atm), the predominant valance state of chromium in the slag samples was Cr2+. Villiers et al. studied the liquidus–solidus phase relations in the system of CaO–CrO–Cr2O3–SiO2 [27]. They found that there is considerable solid solution of chromium oxide in lime and various crystalline calcium silicates (pseudowollastonite, CaSiO3; rankinite, Ca3Si2O7; di-calcium silicate, Ca2SiO4; tricalcium silicate, Ca3SiO5), particularly in lime and Ca2SiO4, the reason of which was that Cr2+ partially substituted Ca2+ sites. Moreover, Cuesta et al. investigated the solid solution mechanisms of B in Ca2SiO4 by testing three nominal solid solution (Ca2−x/2□x/2(SiO4)1−x(BO3)x; Ca2(SiO4)1−x(BO3)xOx/2; Ca2−xBx(SiO4)1−x(BO4)x) [28]. They proposed that boron stabilizes Ca2SiO4 by substituting jointly silicon unites as BO45− and calcium cations by B3+. Therefore, increasing the content of B2O3 in samples would lead to more replacement of SiO44− by BO45− in Ca2SiO4 phase. The BO45− is charge deficient compared with SiO44−; the charge compensation is required to stabilize the structure of di-calcium silicate [29]. As cations for charge compensation, more Cr2+ ions would dissolve into Ca2SiO4 phase to maintain the electro-neutrality.

As shown in Fig. 3, the size of spinel phase in slag is enlarged with B2O3 addition. According to the XRD quantification results in Table 3 and FactSage simulation results in Fig. 4, the mass of spinel phase in slag only slightly changes during cooling. Accordingly, the spinel phase mainly undergoes coarsening during cooling. As shown in Fig. 3, the size increases for spinel phase with addition of B2O3, and some spinel particles with extra large size (larger than 100 μm) could be found. This might be explained by Ostwald ripening that is known as a process in which large crystals grow with time at the expense of the small ones in a system consisting of crystals and liquids [30, 31]. The classical Lifshitz–Slyozov–Wagner (LSW) theory predicts the ripening kinetics very well; the equation is as follows [31]:

where \(\overline{d}\) is the mean crystal size at time t; \(\overline{d}_{0}^{{}}\) is the initial mean crystal size; D is effective diffusion coefficient; σSL is solid–liquid interfacial tension; VS is the molar volume of crystal; c0 is the mass concentration of mobile species in liquid equilibrated with a crystal with infinite large size. The effective diffusion coefficient has a relationship with viscosity according to the well-known Stokes–Einstein equation [32]:

where D is diffusion coefficient of ions in slag; η is viscosity of slag; T is temperature in Kelvin; k is Boltzmann constant; r is radius of ions in slag. It could be seen from Eqs. (2) and (3) that the viscosity of slag plays a dominant role in coarsening of crystals in slag. Li et al. reported that B2O3 addition leads to the formation of low melting point eutectics and weaker polymerization strength, which contribute to the decrease in slag viscosity [33]. Therefore, according to Eqs. (2) and (3), the ripening rate would be promoted with addition of B2O3, and larger size of spinel phase could be found in samples with more B2O3 addition.

Leaching concentration of hexavalent chromium in slags

The leaching concentrations of hexavalent chromium in all samples were determined using US-EPA-3060A method and are shown in Fig. 6. Leaching concentration value of 0.68 mg·L−1 for hexavalent chromium was detected for the sample free of B2O3, which exceeded the inert waste limiting value (0.5 mg·L−1 [34]). The addition of 2% B2O3 reduced the leaching concentration value to 0.206 mg·L−1. However, the hexavalent chromium concentrations increased rapidly with further addition of B2O3. Leaching concentration values of 2.201 and 2.442 mg·L−1 for hexavalent chromium were detected in the leaching solutions of samples with B2O3 = 4% and 6%, respectively. Such high concentrations of hexavalent chromium demonstrated that the stainless steel slags with excess B2O3 addition (> 2%) were unstable for leaching of hexavalent chromium.

The effect of B2O3 addition on leaching behavior of synthetic slag could be interpreted by considering the variation of mineralogical phases in slag. Mineralogical phases of Ca2SiO4, merwinite, akermanite, and spinel were confirmed to be main minerals in slag samples. It is generally accepted that chromium in spinel phase is hardly to be leached out due to its incorporation into spinel structure [2]. Engström et al. investigated the dissolution of merwinite, akermanite, and γ-Ca2SiO4 using HNO3 solution at constant pH, and concluded that the dissolution rates for merwinite and akermanite phase are pH-dependent [35]. When the pH value is higher than 10, dissolution of merwinite and akermanite is considered negligible. The dissolution of γ-Ca2SiO4 is not affected in the same way as merwinite and akermanite when the pH is changed [35]. They also reported that boron-stabilized β-Ca2SiO4 was the only mineral fully dissolved at pH 4, 7 and 10 [36]. Moreover, Teratoko et al. investigated the dissolution behavior of di-calcium silicate in an aqueous solution, and found that the solubility of Ca2SiO4 was much greater than other phases of steelmaking slag [37]. Samada et al. concluded that the existence of Ca2SiO4 enhanced the dissolution of chromium into seawater [38]. At the present work, the leaching agent was 50 mL alkaline solution containing 0.28 M Na2CO3 and 0.5 M NaOH, the pH value of which was 11.5 or greater [18]. Therefore, it can be inferred that Ca2SiO4 is a kind of easy dissolution mineral in slag and could be dissolved at pH = 11.5, while merwinite, akermanite, and spinel phase could not be easily dissolved. The main contribution to the leaching of hexavalent chromium should be Ca2SiO4. According to Table 2, the chromium distributions in Ca2SiO4 for samples with B2O3 = 4% and 6% were significantly higher than those in samples with B2O3 = 0 and 2%. This could be the main reason for the higher leaching concentration of the hexavalent chromium for samples with B2O3 = 4% and 6%. It can be noticed that the Cr2O3 distribution in Ca2SiO4 for sample with B2O3 = 6% is lower than that of sample with B2O3 = 4%, while the leaching of hexavalent chromium in sample with B2O3 = 6% is still higher than that of sample with B2O3 = 4%. This could be due to the dissolution of Cr in matrix phase of sample with B2O3 = 6%. As seen in Table 2, the Cr concentration in matrix phase for sample with B2O3 = 6% is much higher than other samples.

In summary, the size of spinel phase increased with increasing B2O3 content in slags and majority of chromium were found enriched in spinel phase. Whereas the chromium concentration in Ca2SiO4 phase was also enhanced, leading to increasing the leaching concentration of hexavalent chromium. Therefore, the addition content of boron-contained materials must be controlled in practical application. We concluded that excess boron oxide content (> 2%) should be avoided for stabilizing stainless steel slag.

Conclusions

The effect of B2O3 on mineralogical phases and leaching behavior in synthetic CaO–SiO2–MgO–Al2O3–CrOx slag was investigated under the condition of low oxygen partial pressure (PO2 = 10−10 atm). SEM–EDS and XRD were employed to determine the phase composition. The simulations on phase precipitation were also performed by FactSage for comparison. The leaching concentrations of hexavalent chromium were evaluated according to US-EPA-3060A method. The following conclusions could be drawn:

- 1.

The main crystalline phases in slags with different amount of B2O3 addition were observed to be Ca2SiO4, merwinite, spinel, and akermanite.

- 2.

2% B2O3 addition is sufficient to eliminate the disintegration of synthetic slag by suppressing the phase transition to γ-Ca2SiO4.

- 3.

The precipitation of Ca2SiO4 phase was suppressed by adding B2O3; however, excess B2O3 addition (> 2%) would significantly increase chromium concentration in Ca2SiO4 phase and overall chromium distribution in Ca2SiO4 phase.

- 4.

Chromium was found to be enriched in spinel phase. The size of spinel phase increases with increasing B2O3 content in slag.

- 5.

The hexavalent chromium leachability of slag was significantly enhanced with addition of B2O3 higher than 2%, which could be attributed to the enhanced chromium distribution in Ca2SiO4 phase. Therefore, excess boron oxide content (> 2%) should be avoided for stabilizing stainless steel slag.

References

Pillay K, Von Blottnitz H, Petersen J (2003) Ageing of chromium (III)-bearing slag and its relation to the atmospheric oxidation of solid chromium (III)-oxide in the presence of calcium oxide. Chemosphere 52:1771–1779. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0045-6535(03)00453-3

Tossavainen M, Engstrom F, Yang Q, Menad N, Larsson Lidstrom M, Bjorkman B (2007) Characteristics of steel slag under different cooling conditions. Waste Manag 27:1335–1344. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wasman.2006.08.002

Chan CJ, Kriven WM, Young JF (1992) Physical stabilization of the β→γ transformation in dicalcium silicate. J Am Ceram Soc 75:1621–1627. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1151-2916.1992.tb04234.x

Eriksson J, Björkman B (2004) MgO modification of slag from stainless steelmaking. In VII International Conference on Molten Slags, Fluxes and Salts, Cape Town, South Africa.

García-Ramos E, Romero-Serrano A, Zeifert B, Flores-Sánchez H-López M, Palacios EG (2008) Immobilization of chromium in slags using MgO and Al2O3. Steel Res Int 79:332–339. https://doi.org/10.1002/srin.200806135

Cabrera-Real H, Romero-Serrano A, Zeifert B, Hernandez-Ramirez A, Hallen-López M, Cruz-Ramirez A (2012) Effect of MgO and CaO/SiO2 on the immobilization of chromium in synthetic slags. J Mater Cycles Waste Manag 14:317–324. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10163-012-0072-y

Cao LH, Liu CJ, Zhao Q, Jiang MF (2017) Effect of Al2O3 modification on enrichment and stabilization of chromium in stainless steel slag. J Iron Steel Res Int 24:258–265. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1006-706X(17)30038-9

Shu QF, Luo QY, Wang LJ, Chou K (2015) Effects of MnO and CaO/SiO2 mass ratio on phase formations of CaO-Al2O3-MgO-SiO2-CrOx slag at 1673 K and PO2=10-10 atm. Steel Res Int 86:391–399. https://doi.org/10.1002/srin.201400117

Li JL, Xu AJ, He DF, Yang QX, Tian NY (2013) Effect of FeO on the formation of spinel phases and chromium distribution in the CaO-SiO2-MgO-Al2O3-Cr2O3 system. Int J Miner Metall Mater 20:253–258. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12613-013-0720-9

Albertsson GJ, Teng LD, Björkman B (2014) Effect of basicity on chromium partition in CaO-MgO-SiO2-Cr2O3 synthetic slag at 1873 K. Miner Process Extract Metall 123:116–122. https://doi.org/10.1179/1743285513Y.0000000038

Albertsson GJ, Teng LD, Engström F, Seetharaman S (2013) Effect of the heat treatment on the chromium partition in CaO-MgO-SiO2-Cr2O3 synthetic slags. Metall Mater Trans B 44:1586–1597. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11663-013-9939-0

Ghose A, Chopra S, Young JF (1983) Microstructural characterization of doped dicalcium silicate polymorphs. J Mater Sci 18:2905–2914. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00700771

Seki A, Aso Y, Okubo M, Sudo F, Ishizaka K (1986) Development of a dusting prevention stabilizer for stainless steel slag. Kawasaki Steel Tech Rep 15:16–21

Durinck D, Arnout S, Mertens G, Boydens E, Tom Jones P, Elsen J, Blanpain B, Wollants P (2008) Borate distribution in stabilized stainless-steel slag. J Am Ceram Soc 91:548–554. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1551-2916.2007.02147.x

Wu XR, Zhong QB, Shen XM, Cao FB, Wang P, Li LS (2018) Influence of B2O3 on crystallization behavior of Cr-bearing phase in stainless steel slag. In 2018 4th International Conference on Green Materials and Environmental Engineering, Beijing, China.

Shanxi Taigang Stainless Steel Co., Ltd (TISCO). A treatment method of stainless steel slag. Chinese Patent, CN 102586517 A (in Chinese)

Li WL, Xue XX (2018) Effects of boron oxide addition on chromium distribution and emission of hexavalent chromium in stainless-steel slag. Ind Eng Chem Res 57:4731–4742. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.iecr.8b00499

U.S. EPA. United States Environmental Protection Agency. SW-846 Method 3060A. Test methods for evaluating solid wastes, Physical/Chemical Methods, SW-846 On Line, Rev.1, 1996. https://www.epa.gov/sites/production/files/2015-12/documents/3060a.pdf

Sevim F, Demir F, Bilen M, Okur H (2006) Kinetic analysis of thermal decomposition of boric acid from thermogravimetric data. Korean J Chem Eng 23:736–740. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02705920

Shu QF, Li PF, Zhang X, Chou K (2016) Thermodynamics and structure of CaO-Al2O3-3 Mass Pct B2O3 slag at 1773 K (1500°C). Metall Mater Trans B 47:3527–3532. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11663-016-0781-z

Alexander L, Klug HP (1948) Basic aspects of X-ray absorption in quantitative diffraction analysis of powder mixtures. Anal Chem 20:886–889. https://doi.org/10.1021/ac60022a002

Bale CW, Chartrand P, Degterov SA, Eriksson G, Hack K, Ben Mahfoud R, Melançon J, Pelton AD, Petersen S (2002) FactSage thermochemical software and databases. Calphad 26:189–228. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0364-5916(02)00035-4

Durinck D, Tom Jones P, Blanpain B, Wollants P, Mertens G, Elsen J (2007) Slag solidification modeling using the Scheil-Gulliver assumptions. J Am Ceram Soc 90:1177–1185. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1551-2916.2007.01597.x

Barbier J, Hyde BG (1985) The structures of the polymorphs of dicalcium silicate, Ca2SiO4. Acta Crystallogr Sect B 41:383–390. https://doi.org/10.1107/S0108768185002348

Pretorius BE, Snellgrove R, Muan A (1992) Oxidation state of chromium in CaO-Al2O3-CrOx-SiO2 melts under strongly reducing conditions at 1500°C. J Am Ceram Soc 75:1378–1381. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1151-2916.1992.tb04197.x

Wang LJ, Seetharaman S (2010) Experimental studies on the oxidation states of chromium oxides in slag systems. Metall Mater Trans B 41:946–954. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11663-010-9383-3

De Villiers JPR, Muan A (1992) Liquidus-solidus phase relations in the system CaO-CrO-Cr2O3-SiO2. J Am Ceram Soc 75:1333–1341. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1151-2916.1992.tb04191.x

Cuesta A, Losilla RE, Aranda AGM, Sanz J, De la Torre GÁ (2012) Reactive belite stabilization mechanisms by boron-bearing dopants. Cem Concr Res 42:598–606. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cemconres.2012.01.006

Cormier L, Ghaleb D, Delaye JM, Calas G (2000) Competition for charge compensation in borosilicate glasses: Wide-angle x-ray scattering and molecular dynamics calculations. Phys Rev B 61:14495. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.61.14495

Voorhees PW (1985) The theory of Ostwald ripening. J Stat Phys 38:231–252. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01017860

Baldan A (2002) Review progress in Ostwald ripening theories and their applications to nickel-base superalloys Part I: Ostwald ripening theories. J Mater Sci 37:2171–2202. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1015388912729

Edward JT (1970) Molecular volumes and the Stokes-Einstein equation. J Chem Educ 47:261. https://doi.org/10.1021/ed047p261

Li QH, Yang SF, Zhang YL, An ZQ, Guo ZC (2017) Effects of MgO, Na2O, and B2O3 on the viscosity and structure of Cr2O3-bearing CaO-SiO2-Al2O3 slags. ISIJ Int 57:689–696. https://doi.org/10.2355/isijinternational.ISIJINT-2016-569

EC Decision 2003/33/EC. Council Decision of 19 December 2002 establishing criteria and procedures for the acceptance of waste at landfills pursuant to Article 16 of and Annex II to Directive 1999/31/EC. Official Journal L 011, 16/01/2003, p.0027–0049.

Engström F, Adolfsson D, Samuelsson C, Sandström Å, Björkman B (2013) A study of the solubility of pure slag minerals. Miner Eng 41:46–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mineng.2012.10.004

Strandkvist I, Björkman B, Engström F (2015) Synthesis and dissolution of slag minerals-a study of β-dicalcium silicate, pseudowollastonite and monticellite. Can Metall Quart 54:446–454. https://doi.org/10.1179/1879139515Y.0000000022

Teratoko T, Maruoka N, Shibata H, Kitamura S (2012) Dissolution behavior of dicalcium silicate and tricalcium phosphate solid solution and other phases of steelmaking slag in an aqueous solution. High Temp Mater Proc 31:329–338. https://doi.org/10.1515/htmp-2012-0032

Samada Y, Miki T, Hino M (2011) Prevention of chromium elution from stainless steel slag into seawater. ISIJ Int 51:728–732. https://doi.org/10.2355/isijinternational.51.728

Acknowledgements

Open access funding provided by University of Oulu including Oulu University Hospital. This work was supported by the Academy of Finland for Genome of Steel Grant (No. 311934) and Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC Contract No. 51774026).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lin, Y., Luo, Q., Yan, B. et al. Effect of B2O3 addition on mineralogical phases and leaching behavior of synthetic CaO–SiO2–MgO–Al2O3–CrOx slag. J Mater Cycles Waste Manag 22, 1208–1217 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10163-020-01015-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10163-020-01015-4