Abstract

Purpose

This scoping review aimed to summarize the current literature on postpartum psychiatric disorders (e.g., postpartum depression, postpartum anxiety, postpartum post-traumatic stress disorder) and the possible relationship of these disorders to the use of pharmacologic labour analgesia (e.g., epidural analgesia, nitrous oxide, parenteral opioids) to identify knowledge gaps that may aid in the planning of future research.

Sources

PubMed, PsycINFO, CINAHL, and EMBASE were searched from inception to November 9, 2018 for studies that included both labour analgesia and the postpartum psychiatric disorders specified above.

Principal findings

Two reviewers assessed the studies and extracted the data. Of the 990 identified citations, 17 studies were included for analysis. Existing studies have small sample sizes and are observational cohorts in design. Patient psychiatric risk factors, method of delivery, and type of labour analgesia received were inconsistent among studies. Most studies relied on screening tests for diagnosing postpartum psychiatric illness and did not assess the impact of labour analgesia on postpartum psychiatric illness as the primary study objective.

Conclusions

Future studies should correlate screen-positive findings with clinical diagnosis; consider adjusting the timing of screening to include the antepartum period, early postpartum, and late postpartum periods; and consider the degree of labour pain relief and the specific pharmacologic labour analgesia used when evaluating postpartum psychiatric disorders.

Résumé

Objectif

Cette étude exploratoire avait pour objectif de résumer la littérature actuelle portant sur les troubles psychiatriques postpartum (par ex., dépression postpartum, anxiété postpartum, état de stress post-traumatique postpartum) et la relation possible de ces troubles avec l’utilisation d’une analgésie pharmacologique pour le travail obstétrical (par ex., analgésie péridurale, protoxyde d’azote, opioïdes parentéraux) afin d’identifier les lacunes dans nos connaissances qui pourraient aiguiller la planification de futures recherches.

Sources

Des recherches ont été effectuées dans les bases de données PubMed, PsycINFO, CINAHL et EMBASE de leur création jusqu’au 9 novembre 2018 afin d’en extraire les études incluant des informations concernant l’analgésie du travail et les troubles psychiatriques postpartum spécifiés ci-dessus.

Constatations principales

Deux évaluateurs ont passé en revue les études et extrait les données. Parmi les 990 citations identifiées, 17 études ont été incluses pour analyse. Les études existantes ont de petites tailles d’échantillon et sont conçues comme des cohortes observationnelles. Les facteurs de risque psychiatrique des patientes, le mode d’accouchement et le type d’analgésie reçue pour le travail n’étaient pas uniformes d’une étude à l’autre. La plupart des études s’appuyaient sur des tests de dépistage pour poser un diagnostic de maladie psychiatrique postpartum et n’évaluaient pas l’impact de l’analgésie du travail sur la maladie psychiatrique postpartum comme critère d’évaluation principal.

Conclusion

Les études futures devraient corréler les résultats positifs au dépistage à un diagnostic clinique; envisager d’ajuster le moment de dépistage afin d’inclure la période antepartum ainsi que les périodes du postpartum initial et tardif; et tenir compte du degré de soulagement de la douleur du travail ainsi que de l’analgésie pharmacologique spécifique utilisée pour le travail lors de l’évaluation des troubles psychiatriques postpartum.

Similar content being viewed by others

Childbirth is one of the most painful experiences a woman will endure and is associated with an increased risk of first-time episodes of psychiatric disorders.1 The demands of pregnancy and childbirth make patients vulnerable to psychiatric disorders such as postpartum depression (PPD), anxiety, and stress disorders.2 Women with postpartum psychiatric disorders have high mortality rates, with the highest risk in the first year after diagnosis.3,4 The most common postpartum psychiatric disorder is PPD, which is defined by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fifth edition, as depression (e.g., sadness, loss of interest, insomnia, impaired concentration) that occurs any time in pregnancy or in the first four weeks after delivery.5 It can lead to complications such as emotional lability in the mother6 and pervasive emotional, cognitive, and behavioural effects on the child.6,7

In recent years, the association between pain during childbirth and postpartum psychiatric disorders has been investigated.8,9,10,11 The pain of childbirth has been correlated with postpartum blues, which is characterized as transient mood changes within the first few days after delivery and is rarely associated with complications.12,13,14 Also, the severity of acute postpartum pain may be an independent risk factor for the development of persistent pain and PPD.6,13,15 Postpartum anxiety was found in 16.2% of women six weeks after delivery16 and may coincide with PPD.17 While the association between labour pain and anxiety has not been specifically evaluated, the co-relationship between PPD and postpartum anxiety makes the association plausible.18 The pain of childbirth has been linked with postpartum post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms.19

This scoping review aimed to identify the extent, range, and nature of literature on postpartum psychiatric disorders (PPD, postpartum anxiety, PTSD) and their possible relationship to the use of pharmacologic labour analgesia (epidural analgesia, nitrous oxide, parenteral opioids) to identify knowledge gaps that may help plan future research.

Methods

Search strategy

The electronic databases (PubMed, EMBASE, CINAHL, and PsycINFO) were systematically searched from inception until November 9, 2018. A search strategy (Appendix A) was developed using selected Medical Subject Headings (MeSH), as well as free text variations on terms related to birth, analgesia, and postpartum psychiatric disorders. Reference lists and hand searching of relevant literature, including commentaries, letters to the editor, and review articles, was also completed.

Inclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria were original research published in English or French. Articles with only neonates or infants as subjects were excluded. Eligible studies had to include at least one of the following terms in the abstract or title: “parturient”, “labour”, “analgesia”, and one or more of “PPD”, “postpartum anxiety”, “postpartum PTSD symptoms”, or related terms for postpartum psychiatric disorders (Appendix A). Labour analgesia was limited to pharmacologic techniques, including nitrous oxide, parenteral opioids, or neuraxial analgesia. The study title did not have to link or evaluate the use of labour analgesia on postpartum psychiatric disorders. Study results must have reported an outcome related to postpartum psychiatric diagnoses occurring > 24 hr postpartum.

Study selection

Two reviewers (A.M. and H.M.) independently screened titles and abstracts using the pre-determined inclusion criteria. Full-text of manuscripts that appeared to meet inclusion criteria based on abstract review were further reviewed. Discrepancies were resolved through discussion, with third-party consensus when needed.

Data extraction and analysis

Two reviewers (A.M. and A.S.) independently extracted data from the relevant articles using a pre-determined data extraction form (Appendix B). Study characteristics, participant demographic information, obstetric outcomes, psychiatric risk factors, and outcome measures of interest were established a priori and data were extracted using a standardized form.

Results

Search and screening

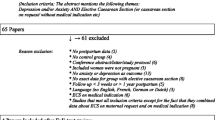

The search strategy yielded 1,088 articles (PubMed 600, Embase 320, PsycINFO 77, CINAHL 91). Citations were managed with the review manager Covidence (systematic review software, Veritas Health Innovation, Melbourne, Australia), and 98 duplicates were removed leaving 990 unique citations. Following title and abstract screening, 909 citations did not match study inclusion, leaving 81 citations for full-text review. Sixty-three citations were excluded during the second screening phase for inappropriate outcomes, non-pharmacologic analgesic interventions, or inappropriate study methodology. The number of articles excluded during each screening phase, and the reasons for exclusion during the second screening phase were recorded using a flow diagram following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement20 (Figure 1). A total of 17 articles were included in the final review. The available literature reviewed postpartum psychiatric disorders and the use of pharmacologic labour analgesia in two major ways—studies that linked pharmacologic labour analgesia to postpartum psychiatric disorders, and studies that linked labour pain to postpartum psychiatric disorders.

A description of study characteristics, including type of labour analgesia is available in Table 1. Patient demographics and risk factors for postpartum psychiatric disorders included in the studies are listed in Table 2. The most commonly utilized form of labour analgesia was labour epidural analgesia (LEA) but details of the epidural technique were not described in all studies (Table 1). Three studies described the LEA technique as a manual bolus of low concentration local anesthetic, with or without opioid, followed by a continuous infusion of local anesthetic solution, with or without opioid.8,10,21 One study described manually administered boluses of a local anesthetic and opioid solution to maintain labour analgesia.22 Only one study specified that the labour analgesia may have included a combined spinal-epidural, but the details of the technique were not provided.23

Types of postpartum psychiatric disorders

The primary objective of most studies (11/17)8,9,10,11,14,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29 focused on identifying depressed mood and a positive PPD screen. Five of the 17 studies25,26,28,30,31 evaluated postpartum PTSD symptoms, and one study32 focused on postpartum anxiety (Table 1). Risk factors for these included postpartum psychiatric disorders are summarized in Table 2.

Measures of psychiatric disorders

Ten of the studies that evaluated PPD symptoms used the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) screening tool.8,9,10,11,14,21,22,24,27,29 The EPDS is a ten-item self-rating scale used to screen for symptoms that are common in women with PPD.33 Responses to items are scored from 0 to 3, with a maximum score of 30. This measure shows excellent psychometric properties and is widely accepted as the preferred screening method for PPD. A cut-off score ≥ 10 identifies a major depressive disorder with sensitivity of > 90% and specificity of > 80%.34,35 One study29 combined this screening tool with a clinical interview that evaluated symptoms using the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Mental Disorders, fifth edition (DSM-5).5 One study23 used administrative coding for depressive disorder at hospital admission to determine the presence of PPD screen-positive patients. The EPDS cut-off score, which determined if the patient may be at risk for PPD, varied between studies, ranging from seven to 14. The time at which the EPDS was evaluated ranged between two days and six months postpartum. More than half of screening evaluations (6/10)8,10,11,21,24,25,27,28,29,31 were completed between four and six weeks postpartum.

Four of the studies that evaluated postpartum PTSD symptoms used the revised Impact of Event Scale (IES-R) screening tool.25,26,28,30 One study30 used the Peritraumatic Distress Inventory and the Peritraumatic Dissociative Experiences Questionnaire screening tools in addition to the IES-R to estimate the risk of postpartum PTSD symptoms. Another study31 used the Traumatic Events Scale and the IES-R to evaluate postpartum PTSD symptoms. The one study32 that examined postpartum anxiety used the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory. Threshold values of the screening tools outlined above are listed in Table 1.

Studies assessing the link between pharmacologic labour analgesia to postpartum psychiatric disorders

Nine studies8,9,10,11,21,22,23,27,29 had a primary objective of evaluating the association of pharmacologic labour analgesia with postpartum psychiatric disorders. Of the six studies with the primary objective of linking LEA and PPD,8,9,10,11,27,29 two studies found that fewer patients screened positive for PPD with LEA compared with patients who chose non-epidural labour analgesia.8,29 In one study, all patients received LEA, and the extent of labour pain relief by LEA predicted lower PPD scores.10 Two studies found no difference between patients who screened positive for PPD with LEA compared with women who did not choose LEA.11,27 One study found no difference in positive PPD screening between patients who received LEA or paracervical blockade and patients who received nitrous oxide, acupuncture, or no pain relief.9 Studies that did not see a difference in the prevalence of PDD based on the use of labour analgesia were adequately powered to detect this outcome.

Zanardo et al. found that EPDS subscales were not different upon discharge in a nitrous oxide group and a matched control group.22 Studies by both Ferber et al. and Gürber et al. controlled for use of labour analgesia in positive PPD screening, but did not look for a relationship between labour analgesia intervention and the outcome.24,25 While all of these studies involved the use of LEA, one study combined LEA with a paracervical block9 and another study evaluated the effect of nitrous oxide on postpartum mental illness.22 One study specifically evaluated postpartum anxiety in patients who received labour analgesia and concluded that postnatal anxiety was not associated with mode of delivery, epidural analgesia, or pain.32

Four studies25,26,30,31 examined the relationship between postpartum PTSD symptoms and labour analgesia. Gosselin et al. concluded that childbirth was related to PTSD symptoms regardless of whether analgesia was used or not.31 Similarly, Gürber et al. noted that depressive symptoms and a negative birth experience were independently predictive of risk for PTSD symptoms when controlling for labour analgesia.25 Boudou et al. found that satisfaction with LEA was predictive of PTSD symptoms.30 Interestingly, Lyons found that higher scores on the Impact of Event Scale (IES), a subjective measure of distress caused by traumatic events, correlated positively with having LEA.26

Studies assessing the link between labour pain and postpartum psychiatric disorders

The link between labour pain and postpartum psychiatric disorders, regardless of analgesia mode, was explored in four studies.14,28,30,31 Boudou et al. found a significant positive correlation between the intensity of childbirth pain and depressed mood postpartum in parturients.14 Emotional reactions caused by pain played an important role in the development of PTSD symptoms postpartum in a subsequent study.30 Séjourne et al. found that pain of childbirth did not show a relationship with postpartum mood in a study where 83% of the cohort received LEA.28 Nevertheless, the pain of delivery and pain immediately postpartum correlated with PTSD symptomatology.28 Similarly, Gosselin et al. found a link between the intensity of childbirth pain, PPD intensity, and the presence of PTSD symptoms, regardless of the use of LEA.31

Discussion

This scoping review, which summarized the possible relationship between labour analgesia, childbirth pain, and postpartum psychiatric disorders reported in the current literature, identified significant variability among existing studies. While some studies were designed to specifically observe the association between pharmacologic labour analgesia and the development of postpartum psychiatric disorders, others determined associations through secondary regression analysis. As it was not the primary objective of some studies to evaluate the effect of labour analgesia on the development of a postpartum psychiatric disorder, caution is required when interpreting the findings.

Study design

In studies examining the linkage between LEA and postpartum psychiatric disorders, the disagreement among study conclusions must be taken in the context of the high rate of LEA use as the use of LEA was not always controlled for in the analysis. Even if LEA was found to be significantly related to any of the postpartum psychiatric outcomes, it may be spurious, with other confounders proving to be more meaningful.10 Most studies were cross-sectional and could not evaluate the true development of postpartum psychiatric disorders, rather only comment on the presence of psychiatric symptoms at the time of assessment. Longitudinal studies examining symptom levels at different time points are required to examine the development of postpartum psychiatric disorders over time.

The studies included in this review were predominantly observational cohorts as randomized-controlled trials are not plausible. Notably, LEA remains the gold standard for pain relief and ethical implications become apparent by attempting to deny this modality of labour analgesia in a randomized-controlled trial. Additionally, randomizing LEA compared with other pharmacologic labour analgesia may result in high cross-over rates reducing the interpretability of results even in the context of intent-to-treat analysis and make it challenging to recruit and retain participants.

Several studies explored the link between labour pain and postpartum psychiatric disorders, regardless of analgesia mode. Labour pain has been correlated with postpartum blues,14 and the severity of acute postpartum pain has been cited as an independent risk factor for the development of persistent pain and depression.6 Recent meta-analysis have also identified an association between level of pain during delivery and postpartum PTSD symptoms.19 Change in pain with therapy has been shown to be more important to patients than pain itself, and percentage of pain improvement has been correlated with improved patient outcomes.10 Only one of the included studies addressed analgesia quality in detail by evaluating pain improvement.10 Therefore, it remains uncertain if analgesia that provides comfort during labour, but is inadequate during delivery, could be a source of postpartum psychiatric disorders. The degree to which labour pain improves with intervention rather than the utilization of pharmacologic labour analgesia needs to be examined with respect to postpartum psychiatric disorders. Additionally, the included studies did not specify the length of time that pain was present prior to initiating LEA, which may relate to the intensity of the experience of labour pain. Future studies could examine if there is a link between duration of unrelieved pain and perceived pain intensity.

By explicitly assessing the relationship between changes in labour pain intensity or pharmacologic labour analgesia and risk of postpartum psychiatric disorders, previously noted associations can be further clarified in future studies.

Controlling for confounders

Antepartum psychiatric risk factors and risk factors for psychiatric illness in the postpartum period varied between studies and were not always controlled. The relationship between LEA and reduced PPD risk may be better explained by mechanisms other than labour analgesia.10 Patient risk factors, such as the role of adverse life events, environmental factors, and a family history of depression should be accounted for to fully understand the development of PPD.36 Future studies evaluating the effect of labour analgesia on postpartum psychiatric outcomes should account for these confounding psychosocial risk factors.

There is evidence that maternal satisfaction with childbirth is influenced by mode of delivery, with less satisfaction associated with assisted and operative deliveries.37 It is plausible that women unsatisfied with their mode of delivery may be more prone to PPD, which was not accounted for in the included studies. Similarly, most of the included studies failed to examine the link between perceived loss of control during delivery and pain intensity. Only one study attempted to address unmatched expectations during labour.27 There is evidence of a negative interaction between unmatched expectations (in terms of women desiring and actually receiving labour analgesia) and the development of PPD.27 Patient expectations for labour analgesia were not accounted for in the remaining studies, so it is uncertain whether this negative interaction plays a role in the risk of PPD. An assessment of mother’s expectations for delivery and labour analgesia would be advantageous in future studies.

Method of postpartum psychiatric assessment

The method of psychiatric evaluation varied among the available studies. The EPDS was the most commonly employed method of screening for PPD, but the threshold score used to identify possible presence of PPD (dichotomous outcome) varied among studies. The available studies evaluating postpartum PTSD symptoms used different screening scales. The lack of a standardized screening threshold makes generalizability of the results difficult, as some studies risk under- or overestimating the effect of labour analgesia on postpartum psychiatric disorders.38 Though screening tools are not intended to make a formal diagnosis, they may be reasonable endpoints because tests are highly sensitive and specific, and positive screening and diagnosis are fairly concordant.39 Studies that use tools to diagnose postpartum psychiatric disease as an endpoint should clearly indicate the findings as positive screens rather than a clinical diagnosis. Application of the DSM-5 criteria combined with clinical examination of the patient would ultimately be the gold standard for diagnosis in future studies.

Time of postpartum psychiatric assessment

The timing in which screening for PPD was completed varied between the studies. It has been suggested that postpartum screening for depression should occur six to 12 weeks after birth and be repeated at least once in the first postnatal year.40 As early as postpartum day two, the EPDS is considered a reliable screening tool for predicting a positive screen later postpartum and determining which patients need close follow-up.41 Depressive symptoms were not detected before epidural analgesia in any of the included studies. Future studies may want to include screening at time points up to one year postpartum to better understand the relationship between labour analgesia and the timing of PPD development.

Conclusions

This scoping review showed that the relationship between pharmacologic labour analgesia and postpartum psychiatric disorders remains uncertain. Existing studies have small sample sizes and are observational cohorts in design. Patient psychiatric risk factors, type of labour analgesia received, and the use of tools to diagnose postpartum psychiatric disease are inconsistent among studies. While some studies were designed to specifically observe the association between labour analgesia and the development of postpartum psychiatric disorders, others have inferred an association through secondary analysis. The ideal study would correlate positive screening with clinical diagnosis, include screening in the antepartum period in addition to early and late in the postpartum period, and consider improvement in pain in addition to pharmacologic labour analgesia when evaluating postpartum psychiatric disorders.

References

Munk-Olsen T, Agerbo E. Does childbirth cause psychiatric disorders? A population-based study paralleling a natural experiment. Epidemiology 2015; 26: 79-84.

Munk-Olsen T, Laursen TM, Pedersen CB, Mors O, Mortensen PB. New parents and mental disorders: a population-based register study. JAMA 2006; 296: 2582-9.

Johannsen BM, Larsen JT, Laursen TM, Bergink V, Meltzer-Brody S, Munk-Olsen T. All-cause mortality in women with severe postpartum psychiatric disorders. Am J Psychiatr 2016; 173: 635-42.

Knight M, Nair M, Tuffnell D, et al. Saving Lives, Improving Mothers’ Care: Surveillance of maternal deaths in the UK 2012–14 and lessons learned to inform maternity care from the UK and Ireland Confidential Enquiries into Maternal Deaths and Morbidity 2009–14. Oxford, UK: University of Oxford; 2016. Available from URL: https://www.npeu.ox.ac.uk/downloads/files/mbrrace-uk/reports/MBRRACE-UK%20Maternal%20Report%202016%20-%20website.pdf (accessed December 2019).

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC; 2013.

Eisenach JC, Pan PH, Smiley R, Lavand’homme P, Landau R, Houle TT. Severity of acute pain after childbirth, but not type of delivery, predicts persistent pain and postpartum depression. Pain 2008; 140: 87-94.

Pearson R, Evans J, Kounali D, et al. Maternal depression during pregnancy and the postnatal period: rRisks and possible mechanisms for offspring depression at 18 years. JAMA Psychiatry 2013; 70: 1312-9.

Ding T, Wang D, Qu Y, Chen Q, Zhu S. Epidural labor analgesia is associated with a decreased risk of postpartum depression: a prospective cohort study. Anesth Analg 2014; 119: 383-92.

Hiltunen P, Raudaskoski T, Ebeling H, Moilanen I. Does pain relief during delivery decrease the risk of postnatal depression? Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2004; 83: 257-61.

Lim G, Farrell LM, Facco FL, Gold MS, Wasan AD. Labor analgesia as a predictor for reduced postpartum depression scores: a retrospective observational study. Anesth Analg 2018; 126: 1598-605.

Nahirney M, Metcalfe A, Chaput KH. Administration of epidural labor analgesia is not associated with a decreased risk of postpartum depression in an urban Canadian population of mothers: a secondary analysis of prospective cohort data. Local Reg Anesth 2017; 10: 99-104.

Adewuya AO. The maternity blues in Western Nigerian women: prevalence and risk factors. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2005; 193: 1522-5.

Zivoder I, Martic-Biocina S, Veronek J, Ursulin-Trstenjak N, Sajko M, Paukovic M. Mental disorders/difficulties in the postpartum period. Psychiatr Danub 2019; 31(Suppl 3): 338-44.

Boudou M, Teissèdre F, Walburg V, Chabrol H. Association between the intensity of childbirth pain and the intensity of postpartum blues (French). Encephale 2007; 33: 805-10.

Degner D. Differentiating between “baby blues,” severe depression, and psychosis. BMJ 2017; DOI: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.j4692.

Matthey S, Barnett B, Howie P, Kavanagh DJ. Diagnosing postpartum depression in mothers and fathers: whatever happened to anxiety? J Affect Disord 2003; 74: 139-47.

Reck C, Struben K, Backenstrass M, et al. Prevalence, onset and comorbidity of postpartum anxiety and depressive disorders. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2008; 118: 459-68.

Wisner KL, Sit DK, McShea MC, et al. Onset timing, thoughts of self-harm, and diagnoses in postpartum women with screen-positive depression findings. JAMA Psychiatry 2013; 70: 490-8.

Grekin R, O’Hara MW. Prevalence and risk factors of postpartum posttraumatic stress disorder: a meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev 2014; 34: 389-401.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman D, PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med 2009; https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.

Riazanova OV, Alexandrovich YS, Ioscovich AM. The relationship between labor pain management, cortisol level and risk of postpartum depression development: a prospective nonrandomized observational monocentric trial. Rom J Anaesth Intensive Care 2018; 25: 123-30.

Zanardo V, Volpe F, Parotto M, Giiberti L, Selmin A, Straface G. Nitrous oxide labor analgesia and pain relief memory in breastfeeding women. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 2017; 24: 3243-8.

Wu YM, McArthur E, Dixon S, Dirk JS, Welk BK. Association between intrapartum epidural use and maternal postpartum depression presenting for medical care: a population-based, matched cohort study. Int J Obstet Anesth 2018; 35: 10-6.

Ferber SG, Granot M, Zimmer EZ. Catastrophizing labor pain compromises later maternity adjustments. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2005; 192: 826-31.

Gürber S, Baumeler L, Grob A, Surbek D, Stadlmayr W. Antenatal depressive symptoms and subjective birth experience in association with postpartum depressive symptoms and acute stress reaction in mothers and fathers: a longitudinal path analysis. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2017; 215: 68-74.

Lyons S. A prospective study of post traumatic stress symptoms 1 month following childbirth in a group of 42 first-time mothers. J Reprod Infant Psychol 1998; 16: 91-105.

Orbach-Zinger S, Landau R, Harousch A, et al. The relationship between women’s intention to request a labor epidural analgesia, actually delivering with labor epidural analgesia, and postpartum depression at 6 weeks: a prospective observational study. Anesth Analg 2018; 126: 1590-7.

Séjourne N, De la Hammaide M, Moncassin A, O’Reilly A, Chabrol H. Study of the relations between the pain of childbirth and postpartum, and depressive and traumatic symptoms (French). Gynecol Obstet Fertil Senol 2018; 46: 658-63.

Suhitharan T, Pham TP, Chen H, et al. Investigating analgesic and psychological factors associated with risk of postpartum depression development: a case-control study. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat 2016; 12: 1333-9.

Boudou M, Séjourne N, Chabrol H. Childbirth pain, perinatal dissociation and perinatal distress as predictors of posttraumatic stress symptoms (French). Gynecol Obstet Fertil 2007; 35: 1136-42.

Gosselin P, Chabot K, Béland M, Goulet-Gervais L, Morin AJ. Fear of childbirth among nulliparous women: relations with pain during delivery, post-traumatic stress symptoms, and postpartum depressive symptoms (French). Encephale 2016; 42: 191-6.

Floris L, Irion O, Courvoisier D. Influence of obstetrical events on satisfaction and anxiety during childbirth: a prospective longitudinal study. Psychol Health Med 2017; 22: 969-77.

Kozinszky Z, Dudas RB. Validation studies of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale for the antenatal period. J Affect Disord 2015; 176: 95-105.

Myers ER, Aubuchon-Endsley N, Bastian LA, et al. Efficacy and Safety of Screening for Postpartum Depression. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2013; No.: 13-EHC064-EF.

Harris B, Huckle P, Thomas R, Johns S, Fung H. The use of rating scales to identify post-natal depression. Br J Psychiatry 1989; 154: 813-7.

Toledo P, Miller ES, Wisner KL. Looking beyond the pain: can effective labor analgesia prevent the development of postpartum depression? Anesth Analg 2018; 126: 1448-50.

Bassano CM, Townsend KM, Walton AC, Blomquist JL, Handa VL. The maternal childbirth experience more than a decade after delivery. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2017; 217(342): e1-8.

Norhayati MN, Hazlina NH, Asrenee AR, Emilin WM. Magnitude and risk factors for postpartum symptoms: a literature review. J Affect Disord 2015; 175: 34-52.

Bhusal B, Bhandari N, Chapagai M, Gavidia T. Validating the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale as a screening tool for postpartum depression in Kathmandu. Nepal. Int J Ment Health Syst 2016; DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13033-016-0102-6.

Austin MP, Highet N; Expert Working Group. Mental Health Care in the Perinatal Period: Australian Clinical Practice Guideline. Melbourne: Centre of Perinatal Excellence - 2017. Available from URL: https://www.cope.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/COPE-Perinatal-MH-Guideline_Final-2018.pdf (accessed December 2019).

El-Hachem C, Rohayem J, Bou Khalil R, et al. Early identification of women at risk of postpartum depression using the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) in a sample of Lebanese women. BMC Psychiatry 2014; DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-014-0242-7.

Author contributions

Allana Munro contributed to the conception of the review, abstract- and full manuscript screening, data extraction, manuscript drafting, and manuscript editing. Hillary MacCormick contributed to the initial literature search, abstract- and full manuscript screening, and manuscript editing. Atul Sabharwal contributed to data extraction. Ronald George contributed to the conception of the study, study design, and manuscript editing.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Funding statement

All authors report there has been no financial support for this work.

Editorial responsibility

This submission was handled by Dr. Hilary P. Grocott, Editor-in-Chief, Canadian Journal of Anesthesia.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix A Search Strategy for labour analgesia and postpartum psychiatric disorders

Embase

((‘postpartum-depression’:ti,ab OR ‘postnatal-depression’:ti,ab OR ‘postpartum-blues’:ti,ab OR ‘postnatal-blues’:ti,ab OR ‘postnatal depression’/exp) AND (epidural*:ti,ab OR analges*:ti,ab OR anesthe*:ti,ab OR anaesthe*:ti,ab OR pain*:ti OR ‘epidural analgesia’/exp OR ‘epidural anesthesia’/exp OR ‘obstetric analgesia’/exp OR ‘analgesia’/exp)) OR ((labor*:ti OR labour*:ti OR deliver*:ti OR ‘labor’/exp OR childbirth:ti OR birth*:ti) AND (epidural*:ti,ab OR analges*:ti,ab OR anesthe*:ti,ab OR anaesthe*:ti,ab OR pain*:ti OR ‘epidural analgesia’/exp OR ‘epidural anesthesia’/exp OR ‘obstetric analgesia’/exp OR ‘analgesia’/exp) AND (ptsd:ti,ab OR ‘post-traumatic-stress’:ti,ab OR ‘posttraumatic-stress’:ti,ab OR anxiety:ti,ab OR ‘postpartum-depression’:ti,ab OR ‘postnatal-depression’:ti,ab OR ‘postpartum-blues’:ti,ab OR ‘postnatal-blues’)

CINAHL:

((TI (“postpartum-depression” OR “postnatal-depression” OR “postpartum-blues” OR “postnatal-blues” OR (MH “Depression, Postpartum”)) OR AB (“postpartum-depression” OR “postnatal-depression” OR “postpartum-blues” OR “postnatal-blues” OR (MH “Depression, Postpartum”))) AND (TI (epidural* OR analges* OR anesthe* OR anaesthe* OR pain* OR (MH “Analgesia, Epidural”) OR (MH “Anesthesia, Epidural”) OR (MH “Analgesia, Obstetrical”) OR (MH “Pain Management”)) OR AB (epidural* OR analges* OR anesthe* OR anaesthe* OR pain* OR (MH “Analgesia, Epidural”) OR (MH “Anesthesia, Epidural”) OR (MH “Analgesia, Obstetrical”) OR (MH “Pain Management”)))) OR (TI (labor* OR labour* OR deliver* OR (MH “Labor”) OR childbirth OR birth*) AND ((TI (epidural* OR analges* OR anesthe* OR anaesthe* OR pain*) OR AB (epidural* OR analges* OR anesthe* OR anaesthe*)) OR (MH “Analgesia, Epidural”) OR (MH “Anesthesia, Epidural”) OR (MH “Analgesia, Obstetrical”) OR (MH “Pain Management”)) AND (TI (PTSD OR “post-traumatic-stress” OR “posttraumatic-stress” OR anxiety OR “postpartum-depression” OR ”postnatal-depression” OR “postpartum-blues” OR “postnatal-blues” OR AB (PTSD OR “post-traumatic-stress” OR “posttraumatic-stress” OR anxiety OR “postpartum-depression” OR ”postnatal-depression” OR “postpartum-blues” OR “postnatal-blues”)

PsycINFO:

((TI (“postpartum-depression” OR “postnatal-depression” OR “postpartum-blues” OR “postnatal-blues” OR (DE “Postpartum Depression”)) OR AB (“postpartum-depression” OR “postnatal-depression” OR “postpartum-blues” OR “postnatal-blues” OR (DE ”Postpartum Depression”))) AND (TI (epidural* OR analges* OR anesthe* OR anaesthe* OR pain* OR (DE “Analgesia”) OR (DE “Anesthesia (Feeling)”) OR (DE “Pain Management”)) OR AB (epidural* OR analges* OR anesthe* OR anaesthe* OR pain* OR (DE “Analgesia”) OR (DE “Anesthesia (Feeling)”) OR (DE “Pain Management”)))) OR (TI (labor* OR labour* OR deliver* OR (DE “Labor (Childbirth)”) OR childbirth OR birth*) AND ((TI (epidural* OR analges* OR anesthe* OR anaesthe* OR pain*) OR AB (epidural* OR analges* OR anesthe* OR anaesthe*)) OR (DE “Analgesia”) OR (DE “Anesthesia (Feeling)”) OR (DE “Pain Management”)) AND (TI (PTSD OR “post-traumatic-stress” OR “posttraumatic-stress” OR anxiety OR “postpartum-depression” OR ”postnatal-depression” OR “postpartum-blues” OR “postnatal-blues” OR AB (PTSD OR “post-traumatic-stress” OR “posttraumatic-stress” OR anxiety OR “postpartum-depression” OR ”postnatal-depression” OR “postpartum-blues” OR “postnatal-blues”)

Pubmed:

(((“postpartum-depression”[Title/Abstract] OR “postnatal-depression”[Title/Abstract] OR “postpartum-blues”[Title/Abstract] OR “mood” [Title/Abstract] “postnatal-blues”[Title/Abstract] OR (“Depression, Postpartum”[Mesh])) AND (((epidural*[Title/Abstract] OR analges*[Title/Abstract] OR anesthe*[Title/Abstract] OR anaesthe*[Title/Abstract])) OR pain*[ti] OR ((((“Analgesia, Epidural”[Mesh]) OR “Anesthesia, Epidural”[Mesh]) OR “Analgesia, Obstetrical”[Mesh]) OR “Pain Management”[Mesh]))) OR ((((labor*[Title] OR labour*[Title] OR deliver*[Title]) OR (“Labor, Obstetric”[Mesh])) OR (childbirth[Title] OR birth*[Title])) AND (((epidural*[Title/Abstract] OR analges*[Title/Abstract] OR anesthe*[Title/Abstract] OR anaesthe*[Title/Abstract])) OR pain*[ti] OR ((((“Analgesia, Epidural”[Mesh]) OR “Anesthesia, Epidural”[Mesh]) OR “Analgesia, Obstetrical”[Mesh]) OR “Pain Management”[Mesh])) AND (PTSD[Title/Abstract] OR “post-traumatic-stress”[Title/Abstract] OR “posttraumatic-stress”[Title/Abstract] OR anxiety[Title/Abstract] OR “postpartum-depression”[Title/Abstract] OR “postnatal-depression”[Title/Abstract] OR “postpartum-blues”[Title/Abstract] OR “postnatal-blues”[Title/Abstract]

Appendix B Extraction tool used for studies that met inclusion criteria

Part A: Study details | |

|---|---|

Title | Month, year published |

Authors | Journal |

Study country | Funding type |

Study type | Study exclusion criteria |

Hospital type | Sample size |

Primary outcome | Multicentre study |

Secondary outcomes | Study duration |

Study inclusion criteria | Study conclusion |

Part B: Demographics | |

|---|---|

Average age | Socioeconomic status |

Marital status | Education |

Ethnicity | Chronic medical conditions |

Part C: Psychiatric risk factors | |

|---|---|

Psychiatric history | History of postpartum depression |

History of depression | Family psychiatric history |

History of trauma of abuse | Domestic violence |

Prenatal class/preparedness for birth | Illegal drugs or alcohol use |

Home support | Fear of childbirth |

History of analgesia use | Season of delivery |

Preterm delivery | Planned pregnancy |

Breastfeeding status | NICU admission |

Appearance, pulse, grimace, activity, respiration (score of baby) | |

Part D: Obstetric factors | |

|---|---|

Parity | Method of delivery |

Major obstetrical comorbidities (diabetes, hypertensive diseases of pregnancy etc.) | |

Part E: Psychiatric outcome measures | |

|---|---|

Screening tool used | Cut-off for screening tool |

Assessment timeline | Psychiatric outcome evaluated |

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Munro, A., MacCormick, H., Sabharwal, A. et al. Pharmacologic labour analgesia and its relationship to postpartum psychiatric disorders: a scoping review. Can J Anesth/J Can Anesth 67, 588–604 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12630-020-01587-7

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12630-020-01587-7