Abstract

Forests are a major and diverse land cover occupying a third of the terrestrial vegetated surface; they store 50 to 65% of terrestrial organic carbon (including the soil) and contribute half to terrestrial productivity. Forest biomass stores close to 80% of all the biomass on Earth. As noted earlier, forests play an important role in the Earth system as carbon stocks, carbon sinks, mediator of the water cycle and as modifier of land surface roughness and albedo. Moreover, forests play a role as habitat for many species, are an economic source of timber and firewood and have recreational value for local populations and touristic visitors. Here, we appraise how ecosystem functions are influenced in particular by biomass and its vertical and horizontal distribution and hypothesize that almost all functions are directly or indirectly related to biomass, in addition to other factors. At landscape or regional scale, heterogeneity of biomass presumably has an important influence on a variety of processes, but there are gaps both in quantifying the heterogeneity of forests globally and in quantifying the effect of this heterogeneity. Similarly, while the role of forests for the global carbon cycle is important, large uncertainties exist regarding stocks, turnover times and the carbon sink function in forest, as an analysis of state-of-the-art carbon cycle and vegetation models shows. Upcoming global satellite missions such as GEDI, NISAR and BIOMASS will be able to address the above uncertainties and lack of understanding in combination with modeling approaches, in particular by exploiting information on vertical and horizontal heterogeneity.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Forests play important biophysical, biogeochemical, hydrological, economic and cultural roles in the Earth system (Fig. 1). Particularly, forests have a central role in the local and global carbon and water cycles with feedbacks into the climate system. Typically, an increase in forest cover is most often associated with a carbon sink from the atmosphere to forest biomass and soils (Guo and Gifford 2002; Houghton et al. 1999; Scurlock and Hall 1998). The impact of forests extends to the hydrological cycle, e.g., via the increased interception of water, deeper rooting and thus more extended sustenance of transpiration than shallow-rooted vegetation (e.g., grasslands and elsewhere) (Bonan 2008; Ellison et al. 2017). An extension in forest cover can further impact belowground water resources, as well as hydrological flows, via a reduction in groundwater recharge, and less runoff is also observed in forested catchments (Zhang et al. 2017). In particular, it has been hypothesized that floods are mitigated by forests through a buffering effect (e.g., Dixon et al. 2016 and elsewhere). Forests also impact the radiation balance and surface roughness, implying climate feedbacks which are variable, and can differ between regional and global scales (Betts et al. 1997; Bonan 2008). The effects on biodiversity can be both positive and negative, and depend on the region and the aspect of biodiversity (e.g., structural, functional, species richness and elsewhere), considered (Schulze and Mooney 2012). For example, structural biodiversity is higher in unmanaged, e.g., old growth, forests compared to, for instance, heavily managed even-aged plantations, implying a richer habitat for animal wildlife and elsewhere. On the other hand, grazed forests and shrubland systems are often more biodiverse than old growth (e.g., beech forests and elsewhere). Hence, it is expected that rather the heterogeneity of biomass than the mean biomass itself relates to many ecosystem properties and functions (e.g., biodiversity and elsewhere). Also, biomass certainly is neither the single factor influencing ecosystem properties and functions, but rather plant traits and their spatial arrangement and temporal dynamics in the ecosystem (e.g., Reichstein et al. 2014a, b; Yguel et al. 2019).

How a hypothetical increase in forest cover in a landscape will influence various aspects of the Earth system regionally and globally. \({\text{A}}\;\mathop{\longrightarrow}\limits{ + }\,{\text{B}}\) means, when A increases, B also increases. \({\text{A}}\;\mathop{\longrightarrow}\limits{ - }\,{\text{B}}\) means when A increases B decreases. + − indicates variable responses are possible. The colors refer to water cycle and geomorphological processes (blue), energy balance and transfers (orange), biological and societal aspects (green), and carbon cycle (brown)

Ecosystem services are defined as the benefits people obtain from ecosystems (Millennium Ecosystem Assessment 2005)—via their functioning. Despite the clear difficulty in quantifying the global benefits of such an ubiquitous good, the economic value of forest ecosystem services has been estimated to be up to more than 10,000 Int$/ha/year (International dollars per hectare per year, De Groot et al. 2012) only for currently known and discovered services. Yet, certainly by far not all of these values are accounted for in regular markets and some values, such as medicinal plants and animals in tropical forest, are even yet undiscovered (Balunas and Kinghorn 2005). And also, the perceived cultural value of forests is not uniform and depends on region, culture and historical epoch. For further insight, the reader is referred to Bengston (1994).

In this short paper, we provide a concise overview of the links between forest biomass and major ecosystem functions with emphasis on carbon cycle aspects. We further illustrate how major processual uncertainties are emerging in global modeling approaches, with emphasis on diagnostics in the global carbon cycle. We finish by highlighting the potential of new Earth observation (EO) data streams to constrain such uncertainties, which will gain from synergistic approaches with complementary data streams for a better understanding of Earth system dynamics.

2 Forest Biomass and Ecosystem Services

Many of the mentioned effects and ecosystem services of forests are not directly observable spatially at the global scale or even at regional scales. For instance, photosynthesis or transpiration cannot be directly observed, but inferred via modeling biophysical relations (Running et al. 2004). Yet, with satellite missions, in particular upcoming LiDAR and RADAR missions, aspects of forests’ structure and functioning can be inferred and correlated with the effects briefly discussed above. The relation between land carbon storage and biomass is trivial, since biomass simply is part of total ecosystem storage. Globally, more than 75% of biomass is stored in forests (Bar-On et al. 2018). Current estimates show that the proportion of carbon in biomass and in soils varies between biomes and is highest in tropical forests (Cveg/Csoil ≈ 0.45), while in high-latitude boreal forests the soil carbon storage can overtake vegetation carbon stocks (Cveg/Csoil ≈ 1/12) (Carvalhais et al. 2014). There is no unique relationship between the current carbon sink and the biomass stock. While classical theory predicts that forests reach an equilibrium after a certain time (Odum 1969), empirical evidence points to carbon sinks in even old-growth forests (Luyssaert et al. 2008). Also, it is easy to build plausible theories and models which predict an absence of a dynamic equilibrium state (steady state) in the soils (Reichstein et al. 2009; Wutzler and Reichstein 2008). These models simply have to relax the classical assumption of first-order decay kinetics. Interestingly, forest age and species diversity has been shown to dampen the interannual variability of gross carbon uptake, which is likely also related to the vertical structure and horizontal heterogeneity of the forest, but also to belowground heterogeneity, although the mechanisms have to be further investigated (Musavi et al. 2017).

Despite the sociocultural role of forests, the concrete relation of the biomass variable to cultural value has to our knowledge not been explicitly empirically studied. Yet it can be hypothesized that the cultural value in industrialized countries increases both with increasing biomass and increasing structure, today, because these forests are relatively rare there. One hypothesis to test is that protected forest areas have larger biomass and larger heterogeneity than non-protected areas (already at the start of protection). As mentioned above, the cultural value is certainly very much society dependent—for instance the tropical forests sometimes have connotations of being dangerous, and in the past “the dark forest” was also associated with danger, e.g., in fairy tales (Lüthi 1986 and elsewhere), negating a high value of forest in former times. However, in society it has been clear the imperative character of quantifying the present and predicting the future of forests. Observation and simulation research has been developed in different directions, e.g., biodiversity, productivity and most recently on the biophysical–chemical feedbacks in the Earth system. In this aspect, the description of the global carbon cycle has been having a central role, especially due to the relevance in prognostics and to the apparent uncertainties in the current knowledge (Friedlingstein et al. 2006, 2013).

3 Uncertainties Related to Carbon Cycle Aspects

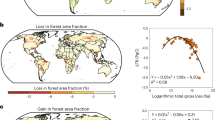

Generally, in dynamic global vegetation models (DGVMs) and global circulation models (GCMs), biomass emerges as the long-term net integral of carbon gains via gross primary productivity (GPP) and losses through autotrophic respiration, litter fall and plant mortality. Changes in vegetation biomass stocks are tightly linked to the interannual variability and decadal trends in net ecosystem C fluxes, given the source–sink strength controls during forest growth trajectories and the substantial emissions of C to the atmosphere from forest disturbances (for a global synthesis see Bonan 2008). At the global scale, the net carbon sink modeled by DGVMs is still very uncertain but is now consistent with the atmospheric growth rate (Le Quéré et al. 2017 and elsewhere). Yet, spatial distribution is much more homogeneous than, for example, observed at flux sites (Fig. 2). There may be several possible reasons for the difference, including spatial aggregation to larger grid cells, which caused the higher variability in ecosystem in local (~ 1 km2) development stages across sites to be dampened (averaged out) for modeled grid cells (~ 2500 km2) that encompass different development stages. Likely, that moderate-resolution biomass change estimates from upcoming missions will also provide an independent benchmark to this mismatch in variability in net carbon balance. However, even at larger scales, substantial uncertainties are observed in different regions (Table 1).

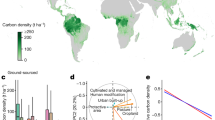

Globally, depending on the modeling ensemble, the estimated global vegetation carbon stocks can deviate from observations on average from 14 to 27%, i.e., for the CMIP5 (Taylor et al. 2012) and TRENDYFootnote 1 ensembles, respectively. Noteworthy is the spread within the modeling ensemble. The ensembles can range from 62 to 70% (range over mean) for the CMIP5 and TRENDY, respectively. In general, the lower the bias in modeled biomass, the better the models capture the global spatial variability that widely spans across biomes (Table 2). But for some regions, even in large geographic regions, the biomass stocks can range more than three times across the TRENDY models, as for example in Central and South America (Li et al. 2017). Particularly in the tropical forests, Negron-Juarez et al. (2015) highlight that the limitations in modeling the C allocation of net primary productions propagate to errors in biomass estimates from CMIP5 models. Further, this analysis reveals that biomass steadily increases with NPP, while observations show a saturation effect, emerging from shorter turnover times of highly productive forests, or lower wood density of fast growing species. This strong relationship between biomass and productivity in models compared to observations is also apparent outside of the tropical regions (Fig. 3), even if the patterns may be confounded by varying forest fraction in the grid cells. This needs to be further investigated. The relationships strongly vary across models, but throughout the majority of them temperature appears to impose the sensitivity on the Cveg to GPP relationship, which in nature could be related to controls on respiratory processes (Amthor 2000), to gradients in tree cover imposed by precipitation and groundwater, or to increasing mortality patterns associated with drought or heat (Thurner et al. 2016).

Global relationship between vegetation carbon (Cveg) and gross primary productivity (GPP) across the different CMIP5 models. Colors represent different mean annual surface temperatures used by the models. Reported in the lower right corner is the Spearman correlation coefficient (rsp) globally (r allsp ), and for different temperature ranges: 10ºC and 0ºC (r 0sp ), 0ºC and 10ºC (r 10sp ), 10ºC and 20ºC (r 20sp ) and above 20ºC (r 35sp ). Significant correlations are observed across temperature intervals, although the association strength between GPP and Cveg per temperature interval can diverge substantially between models

The contrast between modeled and observed biomass, once fluxes are known, highlights discrepancies in simulating loss processes in C cycle models. Regionally, the spatial patterns of background mortality in temperate forests can be associated with climatic drought or with potential frost damage in boreal forests (Thurner et al. 2016), but these patterns do not emerge in state-of-the-art DGVMs (Thurner et al. 2017). Model-based approaches have also shown the 50% reduction in turnover times of carbon in biomass via land use (Erb et al. 2016). Hence, the mismatch between observed and modeled carbon cycle dynamics could explain the disagreement in estimates of forest biomass, although it can also emerge from the challenges in simulating human-driven land use land cover change dynamics, which impose ~ 50% reductions in forest carbon stocks at the global scale (Erb et al. 2018). These estimates imply that, using a bookkeeping approach and assuming no climate effect, land use change emissions have been thrown into the atmosphere circa 375 to 525 PgC. A model ensemble-based estimate, using contemporaneous biomass estimates to constrain modeled trajectories regionally, estimates that one-third of these emissions occurred in the last century (155 ± 50 PgC; Li et al. 2017).

Processes controlling the turnover times of carbon have been shown to be the highest structural discrepancy between models in projections of forest carbon cycle (Friend et al. 2014). Also in CMIP5 models, despite the moderate to substantial agreement between GPP and biomass patterns, the modeled turnover times of carbon in vegetation (Tveg) compared poorly with observations (Tveg = Cveg/GPP; Carvalhais et al. 2014). Globally, the correlation between Tveg and tree cover fraction is significant across the CMIP5 models, though it can range between 0.50, i.e., inmcm4, and 0.88 in the Max Planck Institute for Meteorology Earth System Model at Low Resolution (MPI-ESM-LR). However, between different tree cover ranges the relationship between tree cover and Tveg can change substantially (Table 3). These can emerge from different climate effects on modeled dynamics affecting mortality and, consequently, tree density. For instance, the pattern of the relationship between vegetation carbon turnover times and temperature across the CMIP5 models differs substantially (Fig. 4a), even showing contrasting patterns: see, for example, the Geophysical Fluid Dynamics Laboratory Earth System Model, with generalized ocean layer dynamics (GFDL-ESM2G) compared with the Hadley Centre Global Environmental Model, version 2, Earth System (GEM2-ES) below 0 °C; or the strong control of precipitation on Tveg beyond 20 °C for only half of the models (i.e., CanESM2, CCSM4, IPSL-CM5A-MR, MPI-ESM-LR and NorESM1-M). At global scales, the controls on Tveg do not emerge exclusively from mortality dynamics, but also from carbon allocations strategies and the controls of autotrophic respiration patterns. It would be expected that carbon use efficiency (CUE = NPP/GPP) correlates positively with Tveg, though if the spatial patterns of CUE mostly emerge from changes in tree-to-grass continuum, the emergent pattern should be opposite, since CUE of herbaceous vegetation is higher though its turnover is lower when compared to woody vegetation. But this relationship seems to be far from agreement across models as well (Fig. 4b): In some cases across temperature ranges the CUE seems to be positively related to Tveg (i.e., CanESM2 and MPI-ESM-LR), in other cases it is negatively associated (i.e., bcc-csm1-1, HadGEM2-ES, IPSL-CM5A-MR, MIROC-ESM), while in other cases the patterns are inconclusive (i.e., CCSM4, NorESM1-M). It is worth noting that CUE, despite the lesser association Tveg when compared to tree cover fraction (Table 3), strongly differs between modeling approaches, even showing opposite signs at the global scales. Both MPI-ESM-LR and HadGEM2-ES show a strong rank correlation between tree fraction and Tveg, but show opposite relationships in CUE-to-Tveg, likely underpinning the contrasting patterns of Tveg with different covariates (Fig. 4). These patterns emphasize that a primary focus on vegetation mortality dynamics, from which tree density and other ecosystem properties emerge, should not cast shadow on the importance of understanding the controls carbon allocation and respiratory costs have in predicting long-term changes in turnover times of carbon.

Contrasting the turnover time of vegetation carbon (Tveg, year, estimated as the ratio between Cveg and GPP [Carvalhais et al. 2014]) against temperature (tas, °C), colored by precipitation (mm/year) in CMIP5 models (a). In (b), comparing Tveg against carbon use efficiency (CUE, dimensionless). For the models where tree cover fraction was available, the regions for high tree coverage (higher than 75%) are highlighted in green; while in gray, tree cover fraction is lower than 75% (c)

Each of the CMIP5 models originates from a different Earth system modeling group, team, or even country, and can differ in terms of spatial representativeness as well as in process integration and representation. For instance, models may differ in terms of spatial resolution and number of layers and depths used to simulate water and energy fluxes in the soil. In terms of ecosystem dynamics, three models do not include dynamic vegetation components (i.e., do not explicitly simulate the processes of vegetation mortality and succession; bcc-csm1-1, CCSM4 and NorESM1-M, the latter two force it with land use land cover change datasets); with the exception of Inmcm4, all models embed a representation for crop dynamics; only four models do not include pastures (bcc-csm1-1, CanESM2, Inmcm4 and IPSL-CM5A-MR); and only four include wood harvest (CCSM4, GFDL-ESM2G, MPI-ESM-LR and NorESM1-M); and three include deforestation (GFDL-ESM2G, Inmcm4 and MPI-ESM-LR). In addition, the description of processes of photosynthesis generally relies on Farquhar and Sharkey (1982), or similar representations, but other processes that control the stocking of carbon in vegetation, like autotrophic respiration, litterfall and other metabolic processes, lack a unifying or generally acceptable framework. Apart from the similarities between CCSM4 and NorESM1-M, which may stem from the fact that Nor ESM1-M is partly based on the CCSM4 (Tjiputra et al. 2013), the description of qualitative differences between models falls short in understanding the reasons behind the wide diversity in the relationships between stocks and fluxes, or on the responses of Tveg to climate or CUE across models.

Overall, repeated biomass measurements are key observational constraints on models for both contemporaneous and prognostic simulations of the global carbon cycle. The ability to converge on future projections of the coupled carbon–climate cycle requires a better understanding of phenomena and mechanisms controlling the mortality dynamics of vegetation, as well as processes leading to changes in allocation of assimilates to organ growth and maintenance processes. Here, probably, simulation approaches that omit land use land cover change dynamics, or the target of processes outside that realm, require that DGVMs and GCMs should better compare with patterns of potential biomass (Erb et al. 2018; Exbrayat et al. 2017). Furthermore, continuous monitoring approaches have unique information content at scales that are unprecedented and embed the potential to shed light on controls of growth at larger scales. Ultimately, combining time series at high resolution of remotely sensed biomass fields with models can help disentangle both plant physiology and demography processes at larger scales, ultimately leading to a better understanding of coupled biosphere–atmosphere dynamics and assessment of global forest function.

References

Amthor JS (2000) The McCree–de Wit-Penning de Vries–Thornley respiration paradigms: 30 years later. Ann Bot 86(1):1–20. https://doi.org/10.1006/anbo.2000.1175

Balunas MJ, Kinghorn AD (2005) Drug discovery from medicinal plants. Life Sci 78(5):431–441

Bar-On YM, Phillips R, Milo R (2018) The biomass distribution on Earth. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 115(25):6506–6511. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1711842115

Bengston DN (1994) Changing forest values and ecosystem management. Soc Nat Resources 7(6):515–533

Betts RA, Cox PM, Lee SE, Woodward FI (1997) Contrasting physiological and structural vegetation feedbacks in climate change simulations. Nature 387:796–799

Bonan GB (2008) Forests and climate change: forcings, feedbacks, and the climate benefits of forests. Science 320(5882):1444–1449

Carvalhais N et al (2014) Global covariation of carbon turnover times with climate in terrestrial ecosystems. Nature 514:213–217. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature13731

Chapin FS et al (2006) Reconciling carbon-cycle concepts, terminology, and methods. Ecosystems 9(7):1041–1050. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10021-005-0105-7

De Groot R, Brander L, Van Der Ploeg S, Costanza R, Bernard F, Braat L, Christie M, Crossman N, Ghermandi A, Hein L (2012) Global estimates of the value of ecosystems and their services in monetary units. Ecosyst Serv 1(1):50–61

Dixon SJ, Sear DA, Odoni NA, Sykes T, Lane SN (2016) The effects of river restoration on catchment scale flood risk and flood hydrology. Earth Surf Process Landf 41(7):997–1008

Ellison D, Morris CE, Locatelli B, Sheil D, Cohen J, Murdiyarso D, Gutierrez V, Van Noordwijk M, Creed IF, Pokorny J (2017) Trees, forests and water: cool insights for a hot world. Glob Environ Change 43:51–61

Erb KH, Fetzel T, Plutzar C, Kastner T, Lauk C, Mayer A, Niedertscheider M, Korner C, Haberl H (2016) Biomass turnover time in terrestrial ecosystems halved by land use. Nat Geosci 9(9):674. https://doi.org/10.1038/ngeo2782

Erb KH et al (2018) Unexpectedly large impact of forest management and grazing on global vegetation biomass. Nature 553(7686):73. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature25138

Exbrayat JF, Liu YY, Williams M (2017) Impact of deforestation and climate on the Amazon Basin’s above-ground biomass during 1993–2012. Sci Rep UK. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-15788-6

Farquhar GD, Sharkey TD (1982) Stomatal conductance and photosynthesis. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol 33:317–345. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.pp.33.060182.001533

Friedlingstein P et al (2006) Climate-carbon cycle feedback analysis: results from the (CMIP)-M-4 model intercomparison. J Clim 19(14):3337–3353

Friedlingstein P, Meinshausen M, Arora VK, Jones CD, Anav A, Liddicoat SK, Knutti R (2013) Uncertainties in CMIP5 climate projections due to carbon cycle feedbacks. J Clim 27(2):511–526. https://doi.org/10.1175/JCLI-D-12-00579.1

Friend AD et al (2014) Carbon residence time dominates uncertainty in terrestrial vegetation responses to future climate and atmospheric CO2. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 111(9):3280–3285. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1222477110

Guo LB, Gifford R (2002) Soil carbon stocks and land use change: a meta analysis. Glob Change Biol 8(4):345–360

Houghton RA, Hackler JL, Lawrence KT (1999) The US carbon budget: contributions from land-use change. Science 285(5427):574–578

Jung M et al (2011) Global patterns of land-atmosphere fluxes of carbon dioxide, latent heat, and sensible heat derived from eddy covariance, satellite, and meteorological observations. J Geophys Res Biogeol 116:1–16

Kottek M, Grieser J, Beck C, Rudolf B, Rubel F (2006) World map of the Köppen-Geiger climate classification updated. Meteorol Z 15(3):259–263

Le Quéré C et al (2017) Global carbon budget 2017. Earth Syst Sci Data Discuss 10(1):1–79

Li W et al (2017) Land-use and land-cover change carbon emissions between 1901 and 2012 constrained by biomass observations. Biogeosciences 14(22):5053–5067. https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-14-5053-2017

Lüthi M (1986) The European folktale: form and nature. Indiana University Press, Bloomington

Luyssaert S, Schulze ED, Börner A, Knohl A, Hessenmöller D, Law BE, Ciais P, Grace J (2008) Old-growth forests as global carbon sinks. Nature 455(7210):213–215. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature07276

Millennium Ecosystem Assessment (2005) Ecosystems and human well-being. Island Press, Washington, DC

Musavi T, Migliavacca M, Reichstein M, Kattge J, Wirth C, Black TA, Janssens I, Knohl A, Loustau D, Roupsard O, Varlagin A (2017) Stand age and species richness dampen interannual variation of ecosystem-level photosynthetic capacity. Nat Ecol Evol 1(2):48

Negron-Juarez RI, Koven CD, Riley WJ, Knox RG, Chambers JQ (2015) Observed allocations of productivity and biomass, and turnover times in tropical forests are not accurately represented in CMIP5 Earth system models. Environ Res Lett. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/10/6/064017

Odum EP (1969) Strategy of ecosystem development. Science 164(3877):262–270

Reichstein M, Ågren GI, Fontaine S (2009) Is there a theoretical limit to soil carbon storage in old-growth forests? A model analysis with contrasting approaches. In: Wirth C, Gleixner G, Heimann M (eds) Old-growth forests: function, fate and value. Springer, Berlin, pp 267–281

Reichstein M, Bahn M, Mahecha MD, Kattge J, Baldocchi DD (2014a) Linking plant and ecosystem functional biogeography. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 111(38):13697–13702. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1216065111

Reichstein M, Richardson AD, Migliavacca M, Carvalhais N (2014b) Plant–environment interactions across multiple scales. In: Monson RK (ed) Ecology and the environment. Springer, New York, pp 1–27. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-7612-2_22-1

Rodhe H (1992) Modeling biogeochemical cycles. In: Samuel SS, Charlson RJ, Orians GH, Wolfe GV (eds) Global biogeochemical cycles. Academic Press Limited, London

Running SW, Nemani RR, Heinsch FA, Zhao MS, Reeves M, Hashimoto H (2004) A continuous satellite-derived measure of global terrestrial primary production. Bioscience 54(6):547–560. https://doi.org/10.1641/0006-3568(2004)054%5b0547:Acsmog%5d2.0.Co;2

Saatchi SS et al (2011) Benchmark map of forest carbon stocks in tropical regions across three continents. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 108(24):9899–9904. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1019576108

Schulze ED (2006) Biological control of the terrestrial carbon sink. Biogeosciences 3(2):147–166

Schulze E-D, Mooney HA (2012) Biodiversity and ecosystem function. Springer, Berlin

Scurlock J, Hall D (1998) The global carbon sink: a grassland perspective. Glob Change Biol 4(2):229–233

Taylor KE, Stouffer RJ, Meehl GA (2012) An overview of CMIP5 and the experiment design. Bull Am Meteorol Soc 93(4):485–498. https://doi.org/10.1175/Bams-D-11-00094.1

Thurner M et al (2014) Carbon stock and density of northern boreal and temperate forests. Glob Ecol Biogeogr 23(3):297–310. https://doi.org/10.1111/geb.12125

Thurner M, Beer C, Carvalhais N, Forkel M, Santoro M, Tum M, Schmullius C (2016) Large-scale variation in boreal and temperate forest carbon turnover rate related to climate. Geophys Res Lett 43(9):4576–4585. https://doi.org/10.1002/2016gl068794

Thurner M et al (2017) Evaluation of climate-related carbon turnover processes in global vegetation models for boreal and temperate forests. Global Change Biol 23(8):3076–3091. https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.13660

Tjiputra JF, Roelandt C, Bentsen M, Lawrence DM, Lorentzen T, Schwinger J, Seland O, Heinze C (2013) Evaluation of the carbon cycle components in the Norwegian Earth System Model (NorESM). Geosci Model Dev 6(2):301–325

Wutzler T, Reichstein M (2008) Colimitation of decomposition by substrate and decomposers—a comparison of model formulations. Biogeosciences 5(3):749–759. https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-5-749-2008

Yguel B, Piponiot C, Mirabel A, Dourdain A, Hérault B, Gourlet-Fleury S, Forget P-M, Fontaine C (2019) Beyond species richness and biomass: impact of selective logging and silvicultural treatments on the functional composition of a neotropical forest. For Ecol Manag 433:528–534

Zhang M, Liu N, Harper R, Li Q, Liu K, Wei X, Ning D, Hou Y, Liu S (2017) A global review on hydrological responses to forest change across multiple spatial scales: importance of scale, climate, forest type and hydrological regime. J Hydrol 546:44–59

Acknowledgements

Open access funding provided by Max Planck Society.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix: Data and Methods

Appendix: Data and Methods

The analysis presented here focuses on the outputs from the historical simulations of ten Earth System Models included in the 5th Climate Model Intercomparison Project (CMIP5) (Taylor et al. 2012). From these historical scenario simulations were processed climate variables (temperature and precipitation), but also carbon fluxes (gross and net primary productivity) and vegetation carbon pools. For each variable from each model were computed mean annual values per grid cell between 1982 and 2005. These model outputs were always processed at the native spatial resolution of each model, but, in order to harmonize the spatial resolution between models, the results were aggregated to a common grid of intermediate resolution across models which corresponded to the native resolution of the NorESM1-M model (~ 1.89° × 2.5°, latitude × longitude). The aggregation was based on an area weighted mean per grid cell. Five of those ten models reported tree, grass and bare soil coverages per grid cell. These were also processed to determine the tree fraction per grid cell, defined as the fraction of trees over the fraction of vegetated area.

The observation-based estimates of total vegetation carbon were obtained by putting together spatially explicit estimates for the pantropical regions by Saatchi et al. (2011) and estimated for the northern and temperate forests as estimated by Thurner et al. (2014) as described in Carvalhais et al. (2014). Gross primary production (GPP) is based on the data-driven estimates of Jung et al. (2011). Desert areas were excluded from the analysis, for the comparison between models and data, but also within models. Deserts were defined according to the Köppen–Geiger classification described in Kottek et al. (2006) and to a maximum GPP of 10 gC/m2/year. The original Köppen–Geiger classification was simplified to represent larger bioclimatic gradients, but still translating the seasonality covariation between temperature and precipitation (Table 2). For the CUE, grid cells with GPP values lower than 100 gC m−2 year−1 were filtered out (Fig. 4).

The relative differences (RD) are estimated as the difference between models and observations normalized by observations (shown in percentage). For the RD on the ranges (RANGE), ranges are estimated based on the differences between P90 and P10 (Table 2). The correlation analysis is based on the nonparametric Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient for robustness in associating variables that may not have a linear relationship. The same is assumed in the partial correlation analysis. Partial correlation was used to measure the degree of association between two variables, controlling for the covariation between the dependent variable and a second independent covariate (Table 3).

1.1 Brief Glossary

Carbon pool is the representation of a reservoir of carbon that can match plant organs (e.g., leafs, stems or roots) or soil reservoirs (e.g., litter or humus). Carbon pools are usually divided according to their physical or chemical (or both) properties, e.g., according to the function that the pools have, or the average time span of particles in that pool, or to the vertical locations in the soil. Different models can have different sets of carbon pools, e.g., some can represent branches, others the division between fine and coarse roots) and the representation of the processes that control gains and losses in those pools can also change between models (Rodhe 1992). A carbon pool operates as a carbon sink (or source) when it accumulates (or loses) carbon in time.

CMIP5-the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project, phase 5—is a worldwide collective activity that involves modeling teams that investigate the dynamics of the Earth System via global coupled ocean–atmosphere general circulation models (GCMs). The project designs harmonized modeling experiments to investigate potential impacts of climate change scenarios on the land, oceans and atmosphere of the Earth (Taylor et al. 2012).

Ecosystem service is a direct or indirect benefit that originates from the presence and functioning of an ecosystem (Chapin et al. 2006; Schulze 2006).

Earth System Model-ESM-is a numerical simulation environment that represents the changes in space and time on the three larger domains in the Earth system—land, ocean and atmosphere.

GPP—gross primary productivity—is the flux of carbon from the atmosphere to the ecosystem mediated by photosynthesis (Chapin et al. 2006; Schulze 2006).

Model ensemble is a dataset consisting of outputs from several different models, or of model outputs with different parameterization or initialization settings. Here, the model ensembles refer to datasets originating from different models ran with the same forcing conditions (either ESMs or just global vegetation models).

NEP—net ecosystem productivity—is the net flux of carbon between the ecosystem and the atmosphere that results from the balance between GPP and RECO. Oppositely to NEE (net ecosystem exchange), NEP is defined as a difference between GPP and RECO, meaning that the ecosystem gains carbon when NEP is positive (Chapin et al. 2006; Schulze 2006).

NPP—net primary productivity—is the net flux of carbon that results from the balance between GPP and the autotrophic respiration flux (Chapin et al. 2006; Schulze 2006).

RECO—ecosystem respiration—is the flux of carbon between an ecosystem and the atmosphere that integrates all the respiratory fluxes, i.e., decomposition fluxes (heterotrophic respiration) and plant (autotrophic) respiration (Chapin et al. 2006; Schulze 2006).

Carbon turnover time can be roughly defined as the average time that one particle spends in an ecosystem pool since it is assimilated until it is released (Rodhe 1992).

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Reichstein, M., Carvalhais, N. Aspects of Forest Biomass in the Earth System: Its Role and Major Unknowns. Surv Geophys 40, 693–707 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10712-019-09551-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10712-019-09551-x