Abstract

Although Nickel-Titanium Shape Memory Alloys (NiTi SMAs) are used in a variety of applications due to their shape memory and superelasticity properties, their features of high ductility, temperature sensitivity, and strong work hardening render these materials difficult to machine. The viability of a new approach in improving the machinability through temperature control using chilled air system application was investigated. Differential scanning calorimetry was used to characterise material response to thermal loads. Microstructure phase identification was evaluated with X-ray diffraction. Micro-milling tests were performed using chilled air system and benchmarked to dry cutting and the use of minimum quantity lubricant (MQL). To augment lubrication, chilled air was also applied concurrently with MQL. Results indicated that the application of chilled air reduced cutting temperature and minimised burr height, while their simultaneous application with MQL further improved the machinability. Further investigation was conducted to explore the influence of the ploughing mechanism on machining performance and product quality. The results pointed to higher feed per tooth producing better outcomes. This paper puts forward a new hypothesis that the machinability could be improved by inhibiting or locking in phase transformation through temperature control, and optimising chip thickness, one of the principal parameters of size effect.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

1.1 Shape Memory Alloys

Shape memory alloys (SMAs) are materials which exhibit the two very exceptional properties of pseudoelasticity and shape memory effect (SME). The pseudoelasticity or superelasticity factor in the SMA enables the material to revert to its original form when mechanical loading is applied without any thermal activation. The SME feature subjects the material to a memorisation process (returns to original shape) between two transformation phases, either by temperature or magnetic field [1, 2]. These properties have made SMAs the material of choice in both medical and industrial engineering industries for a diverse range of applications such as (1) the manufacturing of eyeglass frames, surgical stents, orthodontic archwires, and active catheters, and (2) the production of fasteners, sealing and coupling, aerospace actuators (magnetic), sensors and microelectromechanical systems (MEMS), cellular phone antennas, fuel injectors, and small helicopter rotors [3]. These applications could be divided into four primary function categories i.e. free recovery, constrained recovery, actuator, and superelasticity [1].

Among all SMAs, Nickel Titanium-based (NiTi) alloys are the most frequently used due to their additional advantages of strong shape memory effect, superelasticity, biocompatibility, and corrosion resistance [4]. Unconventional cutting processes such as electrical discharge machining, waterjet machining, and laser machining have proven to be better alternative processes compared to conventional cutting in the manufacture of final products [5]. To date, machining of these SMAs by milling has not been exhaustively investigated despite the process being a potentially viable alternative production process. Due to the various degree-of-freedoms in the milling process, complex structures could be produced, an element that is important in facilitating new application areas for NiTi shape memory alloys.

1.2 Challenges in Micro-machining.

Various definitions have been used to describe micro-machining, with some of the more common descriptions in the following:

‘Micromechanical machining to create miniature devices and components with features that range from tens of micrometres to a few millimetres in size’ [6];

‘Machining of dimensions between l and 999 m’ [7];

‘When undeformed chip thickness is less than the grain size of the workpiece, hence, embracing the emphasis on the size effect’ [8, 9]; and

‘Mechanical cutting of features with tool engagement less than 1 mm with geometrically defined cutting edges’ [10].

In this research, the definition of micro-milling is based on the premise that when 1–999 µm diameter end mills are used, the undeformed chip thickness would be comparable to the cutting edge radius or material grain size. This presents a size effect challenge for machining and could be considered a micro-machining domain.

Premature tool breakage and unpredictable tool life have been reported as major issues in this type of microscale cutting [11]. In terms of phase, differential response of phases to cutting influences cutting force and burr formation on grain boundaries found in multiphase materials [12]. Conventional flood coolants also might not be appropriate for micro-machining due to the flow pressure of the lubricants potentially deflecting the cutting tool [10].

1.3 Minimum Chip Thickness

Material removal rate in micro-machining is significantly lower compared to conventional macro-scale machining. The challenge however is in its size effect which pushes the material to spring back for ductile phases [12], and ploughing effect when undeformed chip thickness is comparable or lower than cutting edge radius [13]. When the undeformed chip thickness is lower than the minimum thickness, no chip is generated in machining and no cutting occurs with the material only compressed. Chips start to form when the undeformed chip thickness is equivalent to the minimum thickness. Some elastic deformation would still occur leading to less material removed from the desired depth. A chip is formed and removed only when undeformed chip thickness is significantly higher than the minimum thickness. Ratio selection is therefore critical in micro-milling as it defines the ploughing effect material removal and at the same time influences chip thickness, effective rake angle, and specific cutting energy [13].

1.4 Machinability of NiTi SMAs

The machining of NiTi shape memory alloys often produces very poor workpiece quality due to the high ductility, temperature sensitivity, and strong work hardening features of the materials. Tool wear is also excessively high [14] even when cutting parameters have been optimised [15]. This higher tool wear leads to higher friction and directly contributes to higher cutting temperature [16]. When the temperature exceeds the austenite temperature, the yield strength will in turn increase sharply [17].

The high ductility nature of the material also leads to other serious issues such as poor chip breaking and a high propensity of burrs. The material is only deposited onto the slot side and not separated from the workpiece [14]. Machining strategy also plays an integral role with down milling strategy creating narrower burrs compared to up milling [5]. Burr formation unfortunately cannot be completely avoided. The non-removal of burrs poses two major risks: (1) they could lead to injury especially for workers in the assembly line, and (2) burrs stuck in certain parts of the component could become loose at any point in time and subsequently cause serious damage during operation [18].

Yet, another critical challenge is phase transformation. When NiTi is heated, it begins to transform from martensite to the austenite phase, which is relatively hard and has a considerably higher Young’s modulus. As martensite, NiTi has very low yield strength and could be easily transformed into a new shape by application of external force and thermal load [19]. Kaynak et al.[20] report that machining of martensite NiTi leads to force reduction as compared to preheated work material. Heating the sample changes the phase and renders the material more difficult to machine. Biermann et al.[21] however maintain machining in martensitic phase as more challenging than austenite due to the elements of high ductility and tensile strength which generate high force and high tool wear. Surface quality in austenitic machining is comparatively more acceptable than that produced by the martensitic structure.

In terms of mechanical load, the phase transformation temperature of the workpiece increases when stress is applied to the material [22]. This is consistent with the findings by Fuentes et al.[19] which reported that the austenite finish temperatures of wire increased in a linear relationship to the loads applied. Based on the available studies on machining nickel alloys, the assumption that could be made is the microstructure phase is influenced by operating temperatures and differentiates the machinability of the material. Mechanical loads could also shift the critical temperatures for microstructure.

1.5 Research Motivation

Cutting fluids in general have been the conventional choice to manage the machinability challenges caused by temperature or friction increase and chip management [23, 24]. However there is growing concern that cutting fluids could pose significant health, safety, and environmental hazards [25, 26]. An estimated 80% of all occupational diseases of operators are reportedly linked to skin contact with cutting fluids [27]. The associated costs of such fluids are not limited to their purchase and preparation alone but also maintenance and disposal costs due to many types of cutting fluid not being biodegradable hence necessitating expensive pre-disposal treatments [26, 28].

Recent improvement strategies have included applying different types of cutting fluids in the machining process. Effective unconventional methods such as dry cutting, minimum quantity lubrication (MQL), cryogenic cooling, chilled air, and the use of solid lubricants have been found to be viable substitutes of cutting fluids to optimise machining performance and minimise risks [29]. Many of the researches on NiTi have focused on dry cutting, minimum quantity lubricant, and cryogenic cooling although there is limited or no scientific enquiry to date on the effectiveness of the chilled air system in improving the machinability of the alloys.

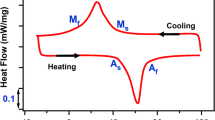

SMAs can exist in either austenite phase or martensite phase with three different crystal structures (twinned martensite, detwinned/deformed martensite, and austenite). Structure transformation occurrence is strongly dependent on the temperature and loads applied to the material as shown in Fig. 1.

Martensite-austenite phase transition (Adapted from [34])

The hypothesis for this study is the premise that effective cooling delivered by chilled air systems could reduce heat generated at tool or workpiece interface, maintain the workpiece material in its easier to cut martensitic phase, and improve the machinability of NiTi SMAs. In addition, since ploughing mechanism could influence the transition from twinned to detwinned martensite, the effect of work hardening could be minimised through the appropriate selection of feed per tooth rate. Experiments to test this hypothesis are detailed in the following section.

2 Experimental Details

2.1 Work Material Characterisation

The workpiece material selected for this study was NiTi. Improving its machinability at the micro scale would enable cost-effective fabrication of micro components such as mini actuators, sensors, micro controllers, micro medical devices, and implantable applications [1]. To link the material thermal cycle to the machining strategy, the first stage was to characterise the material to establish its phase at room temperature and the critical temperature at which it would transform. Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) was used to evaluate the material response to thermal loads.

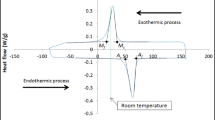

A NiTi sample sheet of 3 mm length, 1.5 mm width, .05 mm thickness, and 4.21 mg in weight was characterised using TA Instrument Q100 Differential Scanning Calorimeter. The material was subjected to a heating–cooling-heating cycle with the temperature range set at between −90 °C and 160 °C. The temperatures for the start of transformation to martensite (martensite start), end of transformation to martensite (martensite finish), start of transformation to austenite (austenite start), and end of transformation to austenite (austenite finish) were plotted in a calorimetric diagram and determined to be 37, 21, 47 and 67 °C respectively (see Fig. 2). These represent the hump transition points of the curve which are critical in the study of the phase transformation and determination of critical transformation temperatures. From Fig. 2, the material was ascertained to be in the martensite phase at room temperature.

XRD analysis further confirmed the major phase in the material was martensite in room temperature (seen in Fig. 3). From the analysis, two pattern lists were matched for phase identification from which it was determined that the monoclinic martensite NiTi phase dominated the phase while cubic austenite was more prominent at the minor phase.

For the microstructure observation, the as-received sample was first mounted on carbon conductive black resin and subsequently ground with three different abrasive paper grits (600, 1200, and 2400). It was then polished with 6, 3 and 1 microns diamond slurry monocrystalline paste to obtain a mirror-like surface free from any scratches. The sample was later etched using a solution of 3.2% hydrofluoric acid (HF), 14.6% nitric acid (HNO3), and 82.2% de-ionised water for 10 s [30]. Essential safety precautions were observed since HF and HNO3 exposure could potentially lead to serious injuries, skin burn, eye damage and even fatality.

Microstructures on the cross-section side of the machined surface depth were imaged using a Carl Zeiss optical microscope. The Intercept Method under ASTM E112 for equiaxed or single phase grain structure was used to measure grain size number [31]; for the as-received sample in Fig. 4, this was ascertained to be 7.362 grains.

2.2 Micro-end Mill Cutting Tools

The cutting tool selected was 2-flutes fine grain solid carbide end mill cutter of .5 mm diameter coated with DURO-S (AlTiN) as shown in Fig. 5. A zero rake angle was selected due to the strength of the cutting edge since a pilot study had previously found positive rake angle cutting tools showing rapid tool wear and chipping.

Prior to the cutting tests, all micro tools were inspected using Quanta 200 Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM) to check their geometry and cutting edge radius feature. This was to ensure there were no unacceptable tool conditions such as multi-cutting edges, chipping, burr, and other defects. The average cutting edge radii of micro tools was measured to be .99 µm.

2.3 Experimental Setup and Machining Conditions

Micro-milling tests were conducted on a NiTi alloy block 70 mm length by 20 mm width and 18 mm height in dimension. The composition of alloy matrix of nickel to titanium was confirmed by Energy Dispersive X-ray Analysis (EDXA) measurement to be 55 to 45 wt% respectively. The tests were undertaken on a Mikron HSM 400 high-speed machining centre. Cutting forces were measured with a Kistler mini-dynamometer type 9256C and cutting temperature analysed using a FLIR Thermo Vision™ A40 thermal camera.

Four different modes of cooling/lubricant systems—dry, chilled air, minimum quantity lubricant, and chilled air applied concurrently with minimum quantity lubricant—were examined in this experiment. A constant cutting velocity of 35 m/min (23,000 rpm), table feed rate of 184 mm/min, feed per tooth of 4 µm, and depth of cut of 30 µm were used as had been established from pilot cutting tests. Ten consecutive passes of 15 mm length each were milled with 40% of tool diameter step over. The material removal rate was 1.1 mm3/min. This was considered reasonable compared to previous studies with 3.15 mm3/min and 0.25 mm3/min [1, 16]. Each test was repeated three times with new cutting tools.

In the chilled air system, a VORTEC adjustable cold air gun (Fig. 6) was used to produce temperatures between − 8.5 °C and − 10 °C at 14 m/s flow velocity. Supplied by VorTech UK, the Adjustable Cold Air Gun System Model 610BSP had a magnetic base and microfilter and used filtered compressed air and vortex tube technology to produce sub-zero air for industrial spot cooling applications. For MQL, 100% biodegradable Coolube® 2210 cutting lubricant was selected with the nozzle positioned at the tool entry point to enable oil droplets adhere to the tool face during the cutting process [32]. The flow rate was .75 ml/min with 13.3 m/s velocity. Since the main objective was to control the workpiece temperature, chilled air was jetted directly onto the workpiece to reduce its temperature at the exit point. The nozzle exit was positioned 15 mm away from the workpiece and directed at a 60° angle to the tool axis.

2.4 Thermal Measurement

A ThermoVision A40 infrared camera, a non-contact temperature measurement featuring high-resolution, real-time imaging and remote monitoring solution, was used to measure workpiece temperature under different cutting conditions. The location of the analysed area was at the end of the slot milled. The distance between the analysed area and camera was 15 cm. The measured surface was earlier painted with matte black paint with emissivity Ɛ = 0.94.

2.5 Cutting Force Measurement

A three-component Kistler Mini-Dynamometer Type 9256C was used in this experiment to measure feed (X), step-over and depth force. The instrument consisted four 3-component force sensors mounted under high preload between the cover plate and two lateral base plates. The very low threshold enabled the measurement of small forces. This type of dynamometer suitable for this experiment due to its rust resistant and rust proof features against the ingress of spray water and cutting fluid. Data acquisition system for force measurement was measured by the Kistler DAQ system Type 5697A1 and the signal amplified using Kistler Type 5070A charge amplifier.

2.6 Surface Roughness, Nano-hardness, Burr size, and Tool Wear

A Keyence VK-X200K 3D Laser Scanning Microscope which measures and analyses 3D surfaces was used to measure burr size and surface roughness. This instrument provides non-contact nanometer-level profile, roughness, and film thickness data on any material. High accuracy 0.5 nm linear scale module was built in to improve the Z-resolution that enabled better detection of surface features. Scanning electron microscope (SEM) images were also used with Image J software to measure tool wear. The hardness of the sub surface machined zone was recorded using a nanoindenter MTS Nano Indenter XP at 400 nm indentation depth. Systematic uncertainties were minimised by first calibrating the equipment to be used. Random uncertainty was addressed by performing each measurement at least five times.

3 Results and Discussion

3.1 Thermal Analysis

Cutting temperature plays a major role in the machinability of temperature sensitive materials such as NiTi as phase transformation is strongly related to temperature. Figure 7 demonstrates the relationship between average workpiece temperatures and cutting conditions. In this cutting, climb-milling strategy was selected. At the beginning of machining, the temperature for all cutting conditions presented higher readings due to full tool entry engagement as shown in Fig. 8. Based on Fig. 2 (in Sect. 2.1), none of the measured temperatures exceeded the austenite start temperature of 47 °C.

From the results, it is apparent that the existence of chilled air significantly contributed to lowering the cutting temperature compared to dry or MQL conditions. Based on this outcome, it could be deduced that convective heat transfer from the chilled air flow was effective in removing heat generated during the cutting process compared to the use of dry and MQL alone. Besides the cold air, the chilled air velocity flow also acted as a medium to remove chips and metal fines on the workpiece and cutting tools.

3.2 XRD Analysis

X-ray diffraction Bruker D8 Discover instrument was used in the investigation of the phase composition of the machined materials. Cobalt (Co) radiation was utilised for scanning and Bruker corundum reference standard employed to calibrate the height of the sample holder using the x-ray beam half cut method. This same process was applied to ensure the experimental sample remained at the correct height with respect to the x-ray beam. A brief pre-scan was conducted to select the 2 theta range with respect to approximate patterns found for NiTi type materials from the International Centre for Diffraction Data (ICDD) database. The diffraction angles were between 40° to 100°, Cobalt radiation 35kV, and current 40 mA. The diffraction was performed along the milled slot.

Figure 9 shows the XRD patterns for specimens at 25 °C for different cutting conditions as compared to the as-received sample. The measurements were done on the floor of the machined slots. The intensities of the XRD peaks were indexed to the International Centre for Diffraction Data (ICDD) powder diffraction Database PDF4 + 2015 and analysed using HighScore Plus software. The diffraction patterns consisted monoclinic martensite (NiTi phase) and rhombohedral (Ni4Ti3 phase), also known as pre-martensite patterns. All the machined samples indicated consistency in patterns and phases. However, for the after machined condition at angles between 44° to 55° and 68° to 74°, the peaks showed noticeable change as compared to the as-received sample whereby they had broadened and merged due to the effect of heat and stress from the machining process.

This effect was also observed in one martensite peak at an angle between 76° and 79° which disappeared after the sample was machined. The result details are shown in Table 1. Only two peaks under the as-received material conditions were matched to a hexagonal structure. Rhombohedral or R-phase structures were found under dry cutting, chilled air, and the combination of chilled air and MQL. Young’s modulus of the R-phase is lower than martensite hence it would be more malleable and possibly improve machinability [33].

3.3 Microstructure Analysis

All samples were etched for 10 s by dipping them into an etchant of 3.2% hydrofluoric acid (HF), 14.6% nitric acid (HNO3), and 82.2% de-ionised water as reported earlier. ASTM average grain size number was taken as an indicator to measure the grain. Microstructure analysis was undertaken only on the machined slot end sides, below the slot floor. The measurement lines were drawn 20, 40 and 60 µm from the slot floor into the material bulk. The linear intercept method was used for measuring the grain sizes.

The subsurface microstructures of dry, chilled air, MQL, and combined chilled air and MQL machined are shown in Fig. 10. After the machining process, all microstructures were altered as compared to the as-received condition in Fig. 4. None of the results showed isotropic orientation. Grain size in dry, chilled air, and MQL showed an assortment of sizes; in contrast, the simultaneous use of chilled air and MQL produced more uniformed grain size albeit larger.

Average grain size number of the subsurface machined area in relation to cutting condition was analysed where a higher value would indicate more grains being intercepted in a particular test line. There was however, no distinct difference between the results, except under chilled air applied concurrently with MQL conditions whereby the grain was larger than as-received, dry, and MQL. Under chilled air, the results were closer to the as-received material compared to other conditions. In terms of grain size, the average size for as-received, dry, chilled air, MQL, and combined chilled air and MQL were measured as 24, 25, 24, 23 and 36 µm respectively. There was no clear basis for this increase in grain size for chilled air combined with MQL although the forces were also considerably lower.

3.4 Cutting Force

Three force components - force in step-over direction (Fx), force in feed direction (Fy) and force in depth direction (Fz)—were measured. From here, the most dominant force was ascertained as Fx. For both Fy and Fz, the force values were significantly lower and less than 1N. Figure 11 shows the cutting force for Fx in terms of its dependence on the cutting condition. The effect of different lubrication modes was apparent in all force directions whereby it could be observed that the use of either chilled air or chilled air simultaneously with minimum quantity lubrication reduced cutting forces compared to the use of dry or minimum quantity lubrication.

Use of oil as lubricant did not significantly reduce the cutting force compared to dry cutting. In contrast, chilled air and chilled air applied concurrently with MQL consistently reduced the cutting force for ten consecutive slots as shown in Fig. 12. These results demonstrated that by reducing the cutting temperature through cooling air, lubrication modes significantly improved the results compared to dry cutting. For the first slot, all the cutting conditions achieved higher readings than the second slot due to the full tool diameter engaged in the cutting.

3.5 Tool Wear

SEM images were used to evaluate the wear modes after micro-milling ten consecutive slots with 40% step over. The tools were imaged from the flat bottom face to focus on each cutting edge. Figure 13 shows examples of wear modes resulting from different modes of cooling. The examples pointed to flank wear as the major mode of wear found in the experiment. The wear zone, the area where the coating had vanished and the substrate material visible, was easily identified with the use of a high-resolution secondary electron detector. The notable reduction of wear zones presented in Fig. 13b, d provided strong evidence of the effectiveness of chilled air. Literature has highlighted the strong adhesive attraction of material on cutting tools as the main problem when machining NiTi; the application of MQL therefore to the machining point reduces adhesion on the end milling cutter resulting in reduced flank wear. This explains the significant positive correlation between the effects of lubrication and cooling action when the chilled air is applied simultaneously with minimum quantity lubricant as shown in Fig. 13d.

Figure 14 shows the average tool flank wear in relation to cutting conditions. The length of the wear zones is around 100 µm with the measurements taken every 10 µm. The results from the combined chilled air and MQL application showed a significant improvement compared to dry cutting and MQL. Under this condition, the application of chilled air in conjunction with minimum quantity lubricant in the form of mist or droplets improved lubrication action and enhanced cooling capability. The repeatability of wear land was improved when the chilled air was combined with MQL. Many of the characteristics needed from conventional cutting fluid could be achieved through this combination with cooling and lubrication effects concurrently provided.

3.6 Surface Roughness

NiTi is widely used in biomedical and aerospace applications where the quality of the end product is critical. The known parameters which heavily influence surface roughness quality are tool edge radius and feed rate. Figure 15 shows the variations of roughness average on different cutting conditions after 10 consecutive slots with all results presenting less than 1 µm roughness. However, due to overlap in the range of results no conclusions could be made about a better system. Future research initiatives could perhaps focus on the variations of feed per tooth to improve surface finish.

3.7 Nano-hardness

Nano-hardness value was evaluated to ascertain the subsurface affected layer zone by means of different lubrication modes. Nano-hardness measurements were indented with a Berkovich indenter at various layers of the machined slot. The hardness measurements were taken along a cross-section of a milled slot with distances from the depth direction fixed at 10, 20, 30, and 40 µm respectively. Figure 16 displays the hardness at 10 µm (closest distance to the milled slot) of each lubrication mode. From the results, it could be concluded that the hardness of machined surface under chilled air was greater than as-received, dry, and MQL. Chilled air promotes better retention of martensite, which is more malleable and could increase hardness to machining force.

3.8 Burr Formation

Location and size of burrs were analysed with top burrs classified based on burr width (wb) and burr height (hb) as displayed in Fig. 17. Burr geometry was described through its cross-sectional area with the average width observed under Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM) and average height measured by 3D Laser Scanning Microscope (see Fig. 18).

Different characteristics of burr are presented in Fig. 19. Dry cutting and MQL showed similar patterns whereby the shapes were lightly bent. Under chilled air, large curvatures of burrs were formed while for the combined chilled air and MQL, the pattern showed cracks on the burr top.

The overall performance of each cutting condition is presented in Fig. 20 and Fig. 21 based on average burr width and height. The smallest burr width values were obtained when chilled air was applied simultaneously with MQL which gave a better performance than dry and chilled air condition. These results might be due to the enhanced lubrication and reduced chip adhesion of MQL as well as the flushing away of chips by the chilled air action.

However, results were varied in terms of burr height with chilled air demonstrating the lowest height while MQL formed the highest burrs. This was strongly influenced by the appearance of the burr shape whereby burrs under the chilled air system were softer and easier to bend compared to the stiffer and harder variations under MQL.

3.9 Size Effect in Machining of Nickel-Titanium Shape Memory Alloys

Once acceptable outcomes were generated, the best performance in cutting condition was selected for further investigation on size effect. It was inferred that changing the chip thickness significantly could bring some machining size effect related impact on the process. A series of experiments was conducted based on three different ratios of maximum undeformed chip thickness to the cutting edge radius. For this study a ratio of maximum undeformed chip thickness to tool edge radius of 40%, 100% and 300% were chosen in order to capture a ploughing mechanism, a balance between ploughing and shear and then shearing mechanism respectively. The feed per tooth fz must exceed a certain critical minimum chip thickness to form a chip. Figure 22 illustrate the ploughing-dominated, trade-off between ploughing and shearing, and shearing-dominated cutting.

Schematic of the effect of minumim chip thickness ratio. (Re, Cutting edge radius; h, undeformed chip thickness) [5]

The machining parameters for this experiment are presented in Table 2.

In micro machining, the material removal rate is substantially lower compared to conventional macro-scale machining. Normally, undeformed chip thickness would be equal or lower in size to the cutting edge radius. In this research, the ratio of undeformed chip thickness to cutting edge radius, rr, was observed based on cutting force, specific cutting force, surface roughness, burr formation, and tool wear to determine the implication of cutting variables on process performance. The values of the rr ratio were .4, 1.0 and 3.0.

3.9.1 Cutting Force and Specific Cutting Force

Cutting forces on X, Y and Z direction as shown in Fig. 23 represent forces on step-over, feed, and depth directions. Force in a step-over direction (Fx) and force in the feed direction (Fy) as the two most influential component forces were measured. Figure 24 shows the cutting force in the step-over direction in relation to its dependence on the rr value. The cutting forces increased with a raise in the ratio of rr. These results matched those observed in conventional milling when the cutting force also rose with feed.

The prevailing forces however were measured in the feed direction. Figure 25 points to there being major changes to the cutting force trend in feed direction as compared to the force in step-over direction with these forces inversely generated. The consequence of the ploughing effect could be seen clearly here when the 0.4 ratio created higher force compared to the 1.0 and 3.0 ratios which were dominated by a trade-off between shearing and ploughing, and completely shearing. This result could be explained by the increase of specific force required to cut a chip when the feed is lowered down to a smaller value than the edge radius as shown in Fig. 26. The specific cutting force is defined by dividing the feed force by feed per tooth, fz and axial depth of cut, ae.

3.9.2 Surface Roughness

Average surface roughness, Ra, was used as the medium to investigate the effect of minimum chip thickness ratio. Figure 27 shows the impact of the rr value on machined surface quality. The main finding here is that surface roughness decreases as rr value increases. A small rr ratio is known to produce a significant negative rake angle. Instead of cutting or shearing, the process might be dominated instead by ploughing and compression. This situation results in a rough machined surface due to elastic recovery of the workpiece.

3.9.3 Burr Formation

Due to its high ductility and tendency to harden when deformed, burr formation is a major issue in the machinability of NiTi alloys. The result in Fig. 28 shows burr size increasing when the rr value decreases. The lower rr signifies the ploughing effect taking place and the cutters not removing the material but pushing it off to the slot side instead. In the higher feed ranges of rr =1.0 and rr =3.0, burr formation was fairly reduced. At this ratio, plastic deformation was still occurring for rr =1 and expected to diminish with the higher ratio 3.0. This is critical as chips are only formed by the shearing process. However, from the outcomes, burrs were still being created although in reduced numbers. Since this could be linked to their high ductility, burr formation could not be entirely removed even when the undeformed chip thickness was increased beyond the cutting edge radius.

3.9.4 Tool Wear

SEM images were used to observe tool wear progression. Figure 29 shows images of used cutting edges after the machining process. From the images it is apparent that coating delamination and flank wear were the dominant wear modes. The decrease in the coating delamination zone as feed rate increases is associated with reduced ploughing effect. This provides strong evidence that coating delamination is driven by the effect of different rr ratios.

Figure 30 indicates the average tool flank wear measured from the bottom cross-sectional image of the end mill. The rate of flank wear is likely to be almost consistent between each ratio of rr, although it could be assumed that repeatability would improve with the rr at 3.0. The outcomes suggest that the lowest rr should be avoided to ensure the amount of wear especially coating delamination is reduced.

4 Discussions

This research has shown that for temperature-sensitive NiTi alloy investigated, the application of chilled air is able to reduce heat generated during the cutting process and prevent the transition from martensite to the austenite phase. Since the martensite phase has better machinability than austenite for this alloy, the use of chilled air ensures that the material remains in the easier-to-cut phase. Whether chilled air would be suitable to prevent phase transitions in NiTi depends largely on the phase transformation temperature. For the material in this study, this was evaluated as 37 °C (martensite start), 21 °C (martensite finish), 47 °C (austenite start), and 67 °C (austenite finish). In this instance, the application of chilled air was a cheaper and easier option to avoid phase transition (austenite phase) especially in microscale cutting.

Weinert and Petzolt (2008) in their study reported that the martensite start, martensite finish, austenite start, and austenite finish temperatures for their workpiece were − 37 °C, − 103 °C, − 46 °C, and 13°C respectively. In this case the use of chilled air (with outlet temperature of − 15°C) is inferred to be inadequate to maintain the material under martensite phase and easier-to-cut phase. Cryogenic cutting becomes a more suitable solution. A scientific study using multiple criteria, comparing the effects of cryogenic cooling, and chilled is an open area for further research.

5 Conclusions

Shape memory alloys are difficult to mechanically machine due to their high ductility, temperature sensitivity, and strong work hardening properties. Controlling cutting temperature is a potentially viable strategy to address this machinability issue. Chilled air systems are expected to be easier to deploy in industry compared to cryogenic machining systems. In this project, the impact of chilled air systems on the machinability of NiTi shape memory alloys was investigated and benchmarked to dry machining and machining with minimum quantity lubricant (MQL).

To compensate for the lack of lubrication in the chilled air system, chilled air was applied concurrently with minimum quantity lubricant. There is an acute lack of literature on the machinability of NiTi alloys in the presence of chilled air systems. The investigation in this research was further extended to explore the effects of undeformed chip thickness to tool edge radius. The key findings of this research work are as follows:

• This paper provides evidence that differential scanning calorimetry could evaluate the critical phase transformation temperatures for shape memory alloys whereby this information could then be used to determine the maximum critical cutting temperature given the difference in machinability for the material phases. Ideally, the cutting process should be undertaken when the material is in easier to cut condition; below the temperature at which the NiTi alloy starts to transform from martensite to austenite.

• Simultaneous use of chilled air and minimum quantity lubricant (MQL) showed significant potential in improving micro scale machinability of NiTi, lowering cutting temperature, reducing cutting force and flank wear, and significantly reducing burr width.

• The ratio of undeformed chip thickness to cutting edge radius could be used as a relevant parameter in the micro-milling of NiTi since it influences cutting force, surface roughness, burr formation, and tool wear.

• The specific cutting force increased considerably when the uncut chip thickness was small due to the effect of the ploughing process when it became dominant.

• The finest surface roughness was attained when the undeformed chip thickness was larger than the tool radius. At this juncture, conventional shearing was the dominant cutting process.

• Burr size was found to be lower with an increase in the chip load. Lower-sized burr formation occurred when undeformed chip thickness was larger than edge radius.

• Based on the results in the size effect experiment, cutting in the ploughing mode consistently demonstrated undesirable results by increasing the specific cutting force, surface roughness, and burr size while inducing coating delamination.

• This paper contributes to machining strategy of the nickel titanium alloys (that start to transform to austenite above room temperature and at 47 °C for the case presented), based on simultaneously use of chilled air and minimum quantity lubricant augmented by finishing in a shear mode cutting regime. Other forms of more severe cooling such as cryogenic machining, can be considered for materials that have significantly lower temperatures for the start of transformation to austenite.

Abbreviations

- a e :

-

Depth of cut

- A f :

-

Austenite phase transformation finish temperature

- A s :

-

Austenite phase transformation start temperature

- Fx:

-

Force in x-direction

- Fy:

-

Force in y-direction

- Fz:

-

Force in z-direction

- f z :

-

Feed per tooth

- hb :

-

Burr height

- M f :

-

Martensite phase transformation finish temperature

- M s :

-

Martensite phase transformation start temperature

- N :

-

Spindle speed

- r e :

-

Cutting edge radius

- r r :

-

Undeformed chip thickness to tool edge radius ratio

- v f :

-

Table feedrate

- wb :

-

Burr width

References

Jani, J. M., Leary, M., Subic, A., & Gibson, M. A. (2014). A review of shape memory alloy research, applications and opportunities. Materials & Design,56, 1078–1113.

Rodrigue, H., Wang, W., Bhandari, B., Han, M., & Ahn, S. (2014). Cross-shaped twisting structure using SMA-based smart soft composite’. International Journal of Precision Engineering and Manufacturing-Green Technology,1(2), 153–156.

Manjaiah, M., Narendranath, S., & Basavarajappa, S. (2014). Review on non-conventional machining of shape memory alloys. Transactions of Nonferrous Metals Society of China,24(1), 12–21.

Kong, M. C., Axinte, D., & Voice, W. (2011). Challenges in using waterjet machining of NiTi shape memory alloys: An analysis of controlled-depth milling. Journal of Materials Processing Technology,211(6), 959–971.

Piquard, R., D’Acunto, A., Laheurte, P., Dudzinski, D., et al. (2014). Micro-end milling of NiTi biomedical alloys, burr formation and phase transformation. Precision Engineering,38(2), 356–364.

Chae, J., Park, S.S., & Freiheit, T. (2006). Investigation of micro-cutting operations. International Journal of Machine Tools and Manufacture, 46(3–4), 313–332.

Masuzawa, T., & Tönshoff, H. K. (1997). Three-dimensional micromachining by machine tools. CIRP Annals -Manufacturing Technology,46(2), 621–628.

Simoneau, A., Ng, E., & Elbestawi, M. A. (2006). Chip formation during microscale cutting of a medium carbon steel. International Journal of Machine Tools and Manufacture,46(5), 467–481.

Liu, X., DeVor, R. E., & Kapoor, S. G. (2004). The mechanics of machining at the microscale: assessment of the current state of the science. Journal of Manufacturing Science and Engineering,126(4), 666.

Dornfeld, D., Min, S., & Takeuchi, Y. (2006). Recent advances in mechanical micromachining. CIRP Annals Manufacturing Technology,55(2), 745–768.

Tansel, I., Rodriguez, O., Trujillo, M., Paz, E., & Li, W. (1998). Micro-end-milling—I. Wear and breakage. International Journal of Machine Tools & Manufacture,38(1998), 1419–1436.

Mian, A. J., Driver, N., & Mativenga, P. T. (2009). Micromachining of coarse-grained multi-phase material. Proceedings of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers, Part B: Journal of Engineering Manufacture,223(4), 377–385.

Aramcharoen, A., & Mativenga, P. T. (2009). Size effect and tool geometry in micromilling of tool steel. Precision Engineering,33, 402–407.

Weinert, K. and Petzoldt, V. (2008) ”Machining NiTi micro-parts by micro-milling”. Materials Science and Engineering: A, 481–482, 672–675.

Weinert, K., & Petzoldt, V. (2004). Machining of NiTi based shape memory alloys. Materials Science and Engineering: A,378(1–2), 180–184.

Kaynak, Y., Karaca, H. E., Noebe, R. D., & Jawahir, I. S. (2013b). Tool-wear analysis in cryogenic machining of NiTi shape memory alloys: A comparison of tool-wear performance with dry and MQL machining. Wear,306(1–2), 51–63.

Benafan, O., Noebe, R. D., Padula, S. A., Gaydosh, D. J., Lerch, B. A., Garg, A., et al. (2013). Temperature-dependent behavior of a polycrystalline NiTi shape memory alloy around the transformation regime. Scripta Materialia,68(8), 571–574.

Aurich, J. C., Dornfeld, D., Arrazola, P. J., Franke, V., Leitz, L., & Min, S. (2009). Burrs—Analysis, control and removal. CIRP Annals - Manufacturing Technology,58(2), 519–542.

Fuentes, J. M. G., Gumpel, P., & Strittmatter, J. (2002). “Phase change behavior of nitinol shape memory alloys influence of heat and thermomechanical treatments. Advanced Engineering Materials,7, 437–451.

Kaynak, Y., Karaca, H. E., Noebe, R. D., & Jawahir, I. S. (2013a). Analysis of tool-wear and cutting force components in dry, preheated, and cryogenic machining of NiTi shape memory alloys. Procedia CIRP,8, 498–503.

Biermann, D., Kahleyss, F., & Surmann, T. (2009). Micromilling of NiTi shape-memory alloys with ball nose cutters. Materials and Manufacturing Processes,24(12), 1266–1273.

Manchiraju, S., Gaydosh, D., Benafan, O., Noebe, R., Vaidyanathan, R., & Anderson, P. M. (2011). Thermal cycling and isothermal deformation response of polycrystalline NiTi: Simulations vs. experiment. Acta Materialia,59(13), 5238–5249.

Kim, H., Seo, K., Kang, K., & Kim, D. (2016). Nano-lubrication: A review. International Journal of Precision Engineering and Manufacturing,17(6), 829–841.

Shokrani, A., Dhokia, V., & Newman, S. T. (2012). Environmentally conscious machining of difficult-to-machine materials with regard to cutting fluids. International Journal of Machine Tools and Manufacture,57, 83–101.

Shashidhara, Y. M., & Jayaram, S. R. (2010). Vegetable oils as a potential cutting fluid—An evolution. Tribology International,43(5–6), 1073–1081.

Lee, C., Choi, Y., Ha, J., & Woo, W. (2017). Eco-friendly technology for recycling of cutting fluids and metal chips: A review. International Journal of Precision Engineering and Manufacturing-Green Technology,4(4), 457–468.

HSE, Medical aspects of occupational skin disease (Vol. 24, pp. 1–8).

Hong, S. Y., & Zhao, Z. (1999). Thermal aspects, material considerations and cooling strategies in cryogenic machining. Clean Technologies and Environmental Policy,1(2), 107–116.

Debnath, S., Reddy, M., & Yi, Q. S. (2014). Environmental friendly cutting fluids and cooling techniques in machining: a review. Journal of Cleaner Production,83, 33–47.

Kaynak, Y., Tobe, H., Noebe, R. D., Karaca, H. E., & Jawahir, I. S. (2014). The effects of machining on the microstructure and transformation behavior of NiTi alloy. Scripta Materialia,74, 60–63.

Methods, S.T. (2010. “Standard test methods for determining average grain size 1”, 96, pp. 1–26.

Mulyadi, I. H., & Mativenga, P. T. (2013). Random or intuitive nozzle position in high-speed milling using minimum quantity lubricant. Proceedings of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers, Part B: Journal of Engineering Manufacture,228(1), 21–30.

Kuhn, G., & Jordan, L. (2002). Fatigue and mechanical properties of nickel-titanium endodontic instruments. Journal of endodontics,28(10), 716–720.

Duerig, T. W., Melton, K. N., & Stockel, D. (1990). Engineering aspect of shape memory alloys. London: Butterworth-Heinemenn Ltd.

Acknowledgements

The first author gratefully acknowledges the financial support of the government of Malaysia and University Malaysia Perlis.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Zainal Abidin, Z., Tarisai Mativenga, P. & Harrison, G. Chilled Air System and Size Effect in Micro-milling of Nickel−Titanium Shape Memory Alloys. Int. J. of Precis. Eng. and Manuf.-Green Tech. 7, 283–297 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40684-019-00040-5

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40684-019-00040-5