Abstract

This paper estimates the effect of obtaining US citizenship on individual-level measures of productivity for foreign-born doctoral recipients from US universities. Becoming a US citizen results in the removal of barriers such as access to public sector occupations and to some sources of government-sponsored research funding which are hypothesized to increase the productivity of foreign-born scientists. We utilize panel data from the Survey of Doctoral Recipients from 1993 to 2013 and individual fixed effects models to control for selection bias in the naturalization decision. Our results indicate that becoming a naturalized citizen increases wages and several measures of academic productivity. In support of our argument, we find that foreign-born workers who naturalize are more likely to utilize research funding from a government agency, but not more likely to work for the government post-naturalization.

Source: Current Population Survey Data 1994–2015

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The number of foreign-born students rose from 7724 to 13,739 compared to US citizens which rose from 19,002 to 23,796.

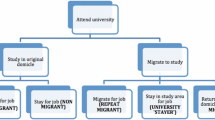

Exact numbers are 68% for a five-year stay rate in 2011 and 68% for a 10-year stay rate. These are higher for graduates from science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) fields, with 79% five-year stay rate for computer science and 77% five-year stay rate for computer/electrical engineering.

After graduation, students have 17 months to obtain employment under a H-1B visa. The H-1B visa permits working in the USA for 3 years (renewable once), and the worker must be sponsored by the employer for permanent residency to remain in the USA beyond this period. Note that there are exceptions to this pathway, including marriage to a citizen.

These stylized facts are also present in our sample, as displayed in Table 2.

We are thankful for a comment from two anonymous referees that noted that some groups are exempt from these requirements such as individuals 50 years of age or older and permanent residents with tenure of 20 years or greater.

The fees for naturalization have risen over the period studied (1993–2013), from $90 to $595 (see Gelatt and McHugh 2007). There is a sharp increase in the year 1999 (from $95 to $225), and another spike in 2008 from $330 to $595 due to backlogged naturalization applications and the introduction of a computerized application process.

Note that though 1993 is the beginning of our sample period for the analysis, 1994 is the first year that the CPS asked respondents about naturalization.

It is important to note that the skill composition and skills possessed by immigrants are critical in the analysis of the effect of immigration on innovation. For example, studying the general pool of immigrants in Italy, Bratti and Conti (2018) find no effect of immigration on innovation even after separately estimating by skill level. This finding implies that the results for the USA may be driven by the prevalence of immigrants trained in STEM fields.

Thus, higher citation counts are typically an accurate indicator of a highly innovative patent.

However, we note that while Borjas (2007) finds limited displacement effects for the average doctoral student, he does find negative displacement effects for white native male students in particular.

This is equivalent to about 10 years.

Foreign-born workers who marry an American spouse can obtain citizenship after 3 years of permanent residency. Though we cannot observe the actual pathway to citizenship, we only observe 5% of naturalized individuals become citizens before the five-year residency requirement.

We thank an anonymous referee for this suggestion.

We use a log transformation of the dependent variable in our preferred specification rather than a count data model because our empirical strategy uses high-dimensional fixed effects. As a robustness check, we estimate a negative binomial model and specifications with log (Y + 1) as the dependent variable with qualitatively similar results.

In this case, the fixed effects model is equivalent to a first difference specification.

Due to the smaller sample of individuals who report applying for a patent (143 employed in academia, 436 employed in private industry, and 20 employed in the federal government), we do not report estimates by academic/industry subsamples for the effect of naturalization on patent applications.

Note that 67% of our academic subsample reports the receipt of government funding at at least one time period, compared to only 39% of private industry employees.

References

Avitabile C, Clots-Figueras I, Masella P (2014) Citizenship, fertility, and parental investments. Am Econ J Appl Econ 6(4):35–65

Azoulay P, Zivin JSG, Li D, Sampat BN (2015) Public R&D investments and private-sector patenting: evidence from NIH funding rules (No. w20889). National Bureau of Economic Research

Blume-Kohout ME, Kumar KB, Sood N (2009) Federal life sciences funding and university R&D (No. w15146). National Bureau of Economic Research

Borjas GJ (2005) The labor-market impact of high-skill immigration. Am Econ Rev 95(2):56–60

Borjas GJ (2007) Do foreign students crowd out native students from graduate programs? In: Stephan PE, Ehrenberg RG (eds) Science and the university. University of Wisconsin Press, Madison

Borjas GJ, Doran KB (2012) The collapse of the Soviet Union and the productivity of American mathematicians. Q J Econ 127(3):1143–1203

Bound J, Turner S, Walsh P (2009) Internationalization of US Doctorate Education. In: Freeman RB, Goroff DL (eds) Science and engineering careers in the United States: an analysis of markets and employment. University of Chicago Press, Chicago, pp 59–97

Bratsberg B, Ragan JF Jr, Nasir ZM (2002) The effect of naturalization on wage growth: a panel study of young male immigrants. J Labor Econ 20(3):568–597

Bratti M, Conti C (2018) The effect of immigration on innovation in Italy. Reg Stud 52(7):934–947

Carruthers JI, Duncan NT, Waldorf BS (2013) Public and subsidized housing as a platform for becoming a United States citizen. J Reg Sci 53(1):60–90

Chang WY, Cheng W, Lane J, Weinberg B (2017) Federal Funding of doctoral recipients: results from new linked survey and transaction data (No. w23019). National Bureau of Economic Research

Chellaraj G, Maskus KE, Mattoo A (2008) The contribution of international graduate students to US innovation. Rev Int Econ 16(3):444–462

Chiswick BR, Miller PW (2009) Citizenship in the United States: the roles of immigrant characteristics and country of origin. In: Constant AF, Tatsiramos K, Zimmermann KF (eds) Ethnicity and labor market outcomes. Emerald Group Publishing Limited, Bingley, pp 91–130

David PA, Hall BH, Toole AA (2000) Is public R&D a complement or substitute for private R&D? A review of the econometric evidence. Res Policy 29(4–5):497–529

Engdahl M (2014) Naturalizations and the economic and social integration of immigrants (No. 2014: 11). Working paper, IFAU-Institute for Evaluation of Labour Market and Education Policy

Finn MG (2014) Stay rates of foreign doctorate recipients from US universities, 2011. Oak Ridge Institute for Science and Education, Oak Ridge

Fougère D, Safi M (2009) Naturalization and employment of immigrants in France (1968–1999). Int J Manpow 30(1/2):83–96

Ganguli I (2017) Saving Soviet science: the impact of grants when government R&D funding disappears. Am Econ J Appl Econ 9(2):165–201

Gelatt J, McHugh M (2007) Immigration fee increases in context, vol 15. Fact Sheet Migration Policy Institute, Washington, DC

Hunt J (2011) Which immigrants are most innovative and entrepreneurial? Distinctions by entry visa. J Labor Econ 29(3):417–457

Hunt J, Gauthier-Loiselle M (2010) How much does immigration boost innovation? Am Econ J Macroecon 2(2):31–56

Islam A, Islam F, Nguyen C (2017) Skilled immigration, innovation, and the wages of native-born Americans. Ind Relat J Econ Soc 56(3):459–488

Jacob BA, Lefgren L (2011) The impact of research grant funding on scientific productivity. J Public Econ 95(9–10):1168–1177

Jasso G, Rosenzweig MR (1986) Family reunification and the immigration multiplier: US immigration law, origin-country conditions, and the reproduction of immigrants. Demography 23(3):291–311

Kerr WR (2007) The ethnic composition of US inventors (No. 08-006). Working paper, Harvard Business School

Kerr WR, Lincoln WF (2010) The supply side of innovation: H-1B visa reforms and US ethnic invention. J Labor Econ 28(3):473–508

National Science Foundation, National Center for Science and Engineering Statistics (2015) Doctorate recipients from U.S. Universities: 2014, special report NSF, vol 16-300

Payne AA, Siow A (2003) Does federal research funding increase university research output? Adv Econ Anal Policy 3(1):1–24

Peri G (2012) The effect of immigration on productivity: evidence from US states. Rev Econ Stat 94(1):348–358

Peri G, Sparber C (2009) Task specialization, immigration, and wages. Am Econ J Appl Econ 1(3):135–169

Peri G, Sparber C (2011) Highly educated immigrants and native occupational choice. Ind Relat J Econ Soc 50(3):385–411

Peri G, Shih K, Sparber C (2015) STEM workers, H-1B visas, and productivity in US cities. J Labor Econ 33(S1):S225–S255

Ransom T, Winters JV (2016) Do foreigners crowd natives out of STEM Degrees and occupations? Evidence from the US Immigration Act of 1990. IZA working paper, DP9920

Steinhardt MF (2012) Does citizenship matter? The economic impact of naturalizations in Germany. Labour Econ 19(6):813–823

Street A (2017) The political effects of immigrant naturalization. Int Migr Rev 51(2):323–343

Vink MP, Prokic-Breuer T, Dronkers J (2013) Immigrant naturalization in the context of institutional diversity: policy matters, but to whom? Int Migr 51(5):1–20

Yang PQ (1994) Explaining immigrant naturalization. Int Migr Rev 28(3):449–477

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Crown, D., Faggian, A. Naturalization and the productivity of foreign-born doctorates. J Geogr Syst 21, 533–556 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10109-019-00301-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10109-019-00301-6