Abstract

This paper presents an effective and reliable non-destructive method to measure the Young Modulus of porous and out of plane Young Modulus of composite materials using sound waves. First, a Finite Element Model based on Representative Volume Element (RVE) is developed to demonstrate how the elastic properties of composite material can be estimated by acoustic measurements using an impedance tube test rig. Second, the results of the experimental measurement campaign was carried out to validate the proposed method. In particular, two soft elastic foams with different density, an epoxy-carbon fibre composite and vynilester-glass fibre composite were tested. In the proposed method, a two-microphone impedance tube setup was used where the measured acoustic pressures at two upstream locations allowed the estimation of the reflection coefficient and the acoustic impedance of the tested materials. Since the acoustic impedance can be expressed as a function of the longitudinal speed of sound (assuming a plane standing wave excitation), the elastic modulus can be estimated which is associated with the speed of sound. The elastic modulus measured using the proposed method were in good agreement with the values obtained by the standard methods such as tensile tests and ultrasound time of flight measurements. The proposed method would allow in an accurate and fast manner the non-destructive evaluation of Young Modulus of porous materials and for the first time the proposed approach is applied successfully to the measurement of out of plane Young modulus of composite materials.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

The rapid assessment of the elastic properties of materials has never been more prevalent than today, due to the acceleration in material development. Advancement of material technology has expanded the number of materials and applications for which these materials can be used. In particular, carbon fibre reinforced polymers (CFRP) have given way to a wide variety of complex materials with material characteristics that vary according to use. For example, CFRP applications range from a very specific highly technology environments (aerospace, Formula 1 and nuclear) to mass market applications (sport equipment, automotive and energy applications). At the same time the advent of commercial 3D printing has added a wide variety of materials that can be customised for a specific use, with highly varying material properties. A further area of interest is the characterisation of biological material where structures can be both anisotropic and heterogeneous making it difficult to assess these materials with traditional engineering methods. The speed and rate of material development has also been enhanced due to ever increasing automation. Thus it is vital to evaluate the material properties (Elasticity, Yield, Hardness, etc.) of these components before they are used in the field.

The focus of this paper is to provide an alternative method for the measurement of the out-of-plane Young’s Modulus (Elastic Modulus - E). The Young’s Modulus of a material defines the relationship between stress and strain, and provides a direct measure of material stiffness. A number of techniques have been used for the determination of the Young’s Modulus, using both destructive and non-destructive testing procedures. These methods include: resonant frequency (in-plane) [1], instrumental indentation [2, 3], traditional engineering methods (tensile tests) and ultrasound techniques [4].

Resonant frequency testing has focused on the evaluation of the Young’s Modulus with regard to thin film materials (in recent times), which generally focus on the calculation of the Young’s modulus of a micro-lever using the value of resonant frequencies obtained in prior experiments, although requiring both a numerical modal analysis as well as evaluation of experimental results. While instrumental indentation is a destructive method that infers from an indentations size and depth the Young’s Modulus.

Traditional engineering methods are very common, highly controlled testing techniques, which generally focus on: tensile, compression and three point bending tests. These tests are highly suited for isotropic materials, as a tensile test can only provide one Young’s modulus (in the direction of tension) but determination of the out-of-plane Young’s Modulus becomes very difficult when investigating anisotropic materials. For example composite materials; as these structures are relatively thin in the out-of-plane direction, further compounding the issue is the manufacturing process which requires individual plies (± 0.25 mm per ply) to be placed on top of one another in the out-of-plane direction, thus requiring an enormous number of plies to be placed to meet the requirements for a tensile test in the out-of-plane direction.

Ultrasound methods provide various advantages over the previously mentioned techniques as smaller specimens can be used with less complicated geometries than mechanical testing methods [5]. Furthermore, the tests are non-destructive, thus more than one elastic constant can be evaluated per specimen. These methods often rely on the determination of the speed of sound through the specimen from which the elastic properties can be obtained [6].

This paper proposes a novel impedance based method to determine the out-of-plane Young’s Modulus of anisotropic materials. The method is based on the evaluation of the acoustic impedance (Z) of a material with the use of a two microphone impedance tube. Impedance tubes are generally used for characterisation of sound absorbing materials, such as wool or polymers, used within building and transport applications.

An impedance tube is a simple apparatus that allows for a plane wave to be generated and propagate down a pipe, this acoustic wave then reflects off test materials. The phase interference between the waves in the pipe, which are incident upon and reflected from the test sample result in the formation of a standing wave pattern in the pipe. Under conditions of no absorption, the incident and reflected waves have the same amplitude resulting in nodes of zero pressure and antinodes with double the pressure. Whereas, if there is absorption by the test sample, the incident and reflected waves have different amplitudes and the nodes do not have zero pressure. The pressure amplitudes at nodes and antinodes can be measured with microphone probes. These measurements can be used to calculate a materials reflection coefficient (R), its absorption coefficient (α), and its impedance (Z) [7, 8].

One of the most common ways to determine the acoustic impedance of materials is with ultrasound, where the impedance is directly related to the longitudinal speed of sound through the material. Recently various authors have developed alternative techniques based on ultrasound in order to determine: the acoustic impedance [9, 10], non-acoustic properties of materials [11] and the Young’s Modulus [12, 13]. One of the issues with ultrasound testing of impedance and Young’s Modulus testing is its ability to evaluate materials with high structural damping or porosity. Acoustic impedance and Young’s Modulus analysis testing requires the accurate determination of the speed of sound through a known thickness. Porous materials result in the scattering of the longitudinal wave which makes it difficult to identify the back wall echo and thus accurately determine the impedance or Young’s Modulus of these types of materials (foams, rubber etc.).

The proposed method provides a solution that is applicable to a wide range of materials from soft foams to hard composite materials, and thus provides an advantage over traditional techniques such as ultrasound for the determination of the out-of-plane Young’s Modulus.

The paper is organized in four sections. The first section of the paper describes the principles and basic assumptions of the proposed method. The method is then numerically validated in the second section. A coupled structural-acoustic FE model is developed including a RVE model of composite material as the tested sample for which the elastic properties are well-know from the literature. The proposed method is applied to the simulation data in a further post-processing step, where the elastic modulus is estimated and compared with the expected one. An experimental measurement campaign on different materials is then reported in the last section of the paper. The experimental setup and the samples used in the experimental campaign are presented. Results evaluated with the proposed method for the tested materials are finally discussed and compared with those given by standard method (tensile testing and ultrasound time of flight).

2 Elastic Modulus Estimation Method

The proposed method is based on the two microphone impedance tube because a plane standing wave condition is required. Starting from the acoustic pressure measurements in two different locations through the pipe, the Transfer Function Method is applied to estimate the reflection coefficient and acoustic impedance. It is demonstrated how the acoustic impedance can be related to elastic properties of the material including the propagation speed of sound.

2.1 Impedance Tube

According to the ASTM E 1050 [14], a two microphone impedance tube is expressed as a one-dimensional wave guide, with a sound source at one end and the acoustic load (typically the test sample) placed at the other end which guarantees a plane standing wave into the duct. In order to maintain plane wave propagation into the duct, the characteristic dimension of the tubes cross section satisfy the following condition:

where K is a geometrical parameter associated to the cross section shape (0.5 for rectangular or square cross section), c the speed of sound and fu the upper frequency limit. In order for a plane wave to fully develop before reaching the pressure acquisition points within the tube a minimum of 3d must be allowed between sound source and the nearest pressure acquisition point. The acquisition points spacing was prescribed to be less than 80% of shortest half wave length of interest

2.2 Transfer Function Method

The Transfer Function Method for acoustic properties measurements was proposed in 1980 by Chung and Blaser [15, 16]. The theory behind this method involve the decomposition of a standing wave into its incident and reflected components using a simple transfer-function relation between the acoustic pressures measured in two different locations as shown in Fig. 1.

According to Fig. 1, the complex sound pressure at the microphone positions can be calculated as

where \( {\widehat{P}}_i \)\( {\widehat{P}}_r \) are the amplitude of the incident and reflecting wave respectively, k0 the wave number in air and x1 and x2 are the microphones coordinates according to the considered reference system.

The reflection coefficient (R) can be expressed through the transfer function (H12) between the complex pressures at two microphone positions and the transfer function of the incident (Hi) and reflecting waves (Hr):

Where s is the microphone spacing and L is the distance between the sample and the closed microphones. Moreover, the transfer function of the incident and reflecting wave at the two microphone positions can be expressed as:

where Pi and Pr are the complex pressures of the incident and reflecting waves.

2.3 Impedance Calibration

Considering that, the Transfer Function Method for the post-processing of data is a complex ratio between the acoustic pressure responses measured by the two microphones system, any mismatch on the amplitude and phase will affect the accuracy of the measurements. Therefore, a correction factor was be defined. So at the first step of the calibration procedure the mics are placed in a rigid plate located at the end of the tube. In this case they were exposed to the same sound pressure and phase, so the ratio of the fast Fourier transform of the two time signals for the two microphones represent a correction factor (Hc) for the amplitude and phase mismatches

which will be applied to the complex measured transfer function between the sound pressures measured by the microphones placed in the standard position (Fig. 1).

where \( {\widehat{H}}_{12}= fft\left({\widehat{p}}_{mic1}\right)/ fft\left({\widehat{p}}_{mic2}\right) \) is the uncorrected (measured) transfer function.

Moreover, the thermal viscous losses, which induce attenuation on the propagating incident and reflected waves within the tube are not negligible [14]. In order to take into account tube attenuation, a complex wave number must be introduced where the imaginary part represent the attenuation constant.

If the real part is linearly dependent on the frequency and inversely proportional to the speed of sound (k = 2πf/c), the imaginary part is not a priori known, except to empirical relationship [14, 17].

Therefore the attenuation constant can be measured [17].

Considering an acoustically rigid and high reflection material sample and measuring the transfer function (corrected for the amplitude and phase mismatches), the Eq. (5) can be solved assuming a reflection coefficient (R) of 1 and including a complex wave number

Equation (11) can be solved numerically for k” by means of a Newton-Raphson iteration scheme and assuming an initial guess the empirical value

where d is the tube diameter and A is a constant (A = 0.0194 [18]).

When the imaginary part is estimated, the complex wavenumber can be included into the Eq. (5) for the experimental data post-processing.

2.4 Elastic Modulus Estimation

In this section the proposed method is presented starting from the sound wave propagation at the interface of two different media.

Consider the air-solid interaction shown in Fig. 2, with a plane incident sound wave. Due to the difference in acoustic properties between two media, the energy associated to the incident wave will be in part reflected and in part transmitted at the interface.

At the interface three boundary conditions must be satisfied. First, the particle velocity normal to the bounding surface and the pressure variation must be continuous. Continuity of normal stress must be guaranteed and finally zero tangential stress is required since the fluid cannot support viscous stress (assuming an ideal non-viscous liquid). These boundary conditions can be written in term of velocity potentials, which can be expressed as plane wave solutions to the wave equation [19, 20] and solved in terms of reflection and transmission coefficients. In particular, the reflection coefficient can be written as

where θS is the angle of the propagating shear waves.

Since in a solid the wave propagation is associated to longitudinal and shear waves, ZL and ZS represent the longitudinal and shear characteristic impedance respectively, while Z1 is the characteristic impedance of the fluid

So the characteristic impedance is a function of the density (ρ1 density of fluid - ρ2 density of solid media) and the relative propagation velocity (V1 speed of sound in the fluid, VLspeed of propagating longitudinal waves, VS speed of propagating shear waves).

Because of longitudinal and shear wave are involved, an effective impedance (Zeff) can be defined

so that the reflection coefficient becomes

The geometrical laws of reflection of sound waves are the same as those that apply to light waves unless the length of the sound waves is not comparable with the linear dimensions of the reflecting objects [21]. As the wavelength is small relative to the dimension of the reflectors, the Snell’s law can be applied

In the particular case of plane and normal incident waves, the incidence angle is zero (θi=0), so according to Eq. (17) results in reflection and transmission angles of zero and only longitudinal waves are transmitted into the media, so from Eq. (16) the reflection coefficient can be simplified as follows:

where Z1 is the characteristic impedance of fluid (Z1 = ρf Cf, with Cf speed of sound in the fluid) and Z2 is characteristic impedance of solid (Z2 = ρsCLs) which is a function of the longitudinal sound speed in the solid.

The speed of sound describes the speed of sound waves passing through an elastic medium and varies with the medium employed as well as with the properties of the medium, in particular it is closely related to the stiffness of the material. When considering solid materials, there is non-zero stiffness both for volumetric and shear deformations. Hence, in a solid it is possible to generate sound waves with different velocities dependent on the deformation mode. When the lateral dimension (thickness) of the medium is much smaller than the incident wavelength the speed of sound can be expressed by the relation

Considering a normal incident plane wave, as we demonstrated only longitudinal waves will pass through the solid, so the speed of sound in Eq. (19) represents the longitudinal speed of sound. Moreover the Elastic Modulus included in Eq. (19) represents the out of plane component of elastic properties of the material (E3).

Now combining the Eqs. (18) and (19) and assuming the acoustic impedance under plane incident wave condition (Z2 = ρsCLs), the Elastic Modulus of material can be expressed as:

In conclusion the elastic modulus of the material can be estimated using acoustic measurement. Starting from the sound pressure measurements in two different position through an impedance tube and applying the transfer function method the acoustic impedance and the reflection coefficient can be measured and the elastic modulus can be estimated then through the Eq. (20).

3 Numerical Simulation

In order to validate the proposed method, a numerical model, based on the Representative Volume Element (RVE), was developed. An RVE model of composite material for which the elastic properties were known from literature, was developed and included in the FE simulation.

First a coupled acoustic-structural harmonic analysis was considered in order to simulate the impedance tube test rig. The simulation data in terms of sound pressures acquired during the simulation was used as input data and the elastic modulus was estimated by the proposed method and compared with the expected one.

Moreover a static structural analysis was implemented using the same RVE model in order to simulate a standard tensile testing and estimate the elastic modulus according to the Hooke’s law. The results was then compared with the expected one and with the elastic modulus extracted by the proposed method.

3.1 Representative Volume Element (RVE)

The Representative Volume Element (RVE) [22,23,24,25] is a powerful and commonly used approach for numerical modelling and elastic behaviour analysis of composite materials and general periodic structures [26,27,28,29]. Different RVE models have been developed, but in this work the Homogenization Theory was taken into account which was shown to give more accurate estimates of effective stiffness for periodic composite material [26].

The homogenization theory is based on two assumptions. The fields vary on multiple scales due to the existence of microstructure, and the microstructure is assumed spatially periodic. Starting from such assumption the field variables are approximated by an asymptotic expansion

where \( {\mathrm{u}}_{\mathrm{i}}^{\upeta} \)is the exact value of the field variable, u0i is the macroscopic or average value of the field variable, u1i, u2i, etc. are perturbations in the field variables due to the microstructure, xi are the global level coordinates, yi are the micro level coordinates, and η the ratio of the microstructure size to the total size of the analysis region. In the elasticity theory u0i would be the continuum level displacements while u1i would be the microstructural displacements. The relation between the macro and micro coordinate can be expressed

Applying the derivatives with respect to xi to the expansion of the displacement (Eq. (21)) and neglecting the higher order terms of the weak form of equilibrium equations governing the mechanical behaviour of composite material, the small deformation strain tensor can be written as

where

εij is the microstructural strain tensor, \( {\overline{\varepsilon}}_{ij} \) is the macroscopic strain tensor and \( {\varepsilon}_{ij}^{\ast } \) is the fluctuating microstructural strain tensor which is assumed to vary periodically.

In the same way, the virtual strain tensor can be expressed

where

Assuming the virtual displacement varying only on microscopic level and is constant on the macroscopic level (\( {\varepsilon}_{ij}^0(v) \)=0), and assuming η goes to zero in the limit, then the standard weak form of equilibrium equation can be written as

where Ω is the total of macroscopic and microscopic domain of composite material, VRVE is the volume of RVE and Dijkl is the stiffness tensor. Equation (27) is satisfied if the integral over RVE is zero, so the equilibrium equations may be written

For linear problem in 3-dimensions, \( {\overline{\varepsilon}}_{kl}(u) \), which is unknown apriori, can be written as a linear combination of unit strains as following

Applying the symmetry of strain states and substituting the unit strains on the right hand side of Eq. (28), the stress tensor can be derived as

A set of six auxiliary problems have to be solved for \( {\varepsilon}_{kl}^{\ast kl} \) in Eq. (28) using Eq. (30)

To ensure periodicity of the strain field \( {\varepsilon}_{pm}^{\ast kl} \) in Eq. (28) the value of \( {\varepsilon}_{ij}^{\ast } \) for any arbitrary \( {\overline{\varepsilon}}_{kl} \) can be written as

So the relation between local RVE strain and the average strain can be written

Finally the effective stiffness tensor which relates average stress and average strain can be estimated from Mijkl by writing the Hooke’s law at microscopic level and then integrating over the volume of RVE and divide by the volume of RVE

3.2 Static Structural Analysis

A static structural analysis was used to extract a preliminary indication of the elastic modulus of the sample. Considering an RVE approach, and assuming the material to behave as a linear elastic solid, a constant axial loading and fixed support boundary conditions was applied on the sample (Fig. 3). The two ends of the RVE along the transverse direction are marked as a fixed area and load area respectively. A displacement boundary condition was prescribed at the fixed area (ux = uy = uz = 0), while a force was applied as the loading condition to the load area. The applied load is confined in the elastic range, so measuring the stress induced by the loading conditions and the relative strain status, the Hooke’s law can provide an estimation about the elastic modulus of the sample:

Where σ3 and ε3 are the tensile stress and strain respectively along the loading direction.

In order to obtain the averaged stress-strain results for a certain prescribed load and boundary conditions, periodic boundary condition [30,31,32,33,34] need to be applied on the RVE. The periodic boundary conditions were implemented by creating identical mesh on opposite faces of RVE to ensure the same coordinates are tangential to the face.

3.3 Coupled Acoustic-Structural Analysis

Then a coupled acoustic structural analysis was carried to simulate in-silico the impedance tube measurements and verify the proposed approach numerically. In acoustic fluid-structural interaction (FSI) problems, the structural dynamic equation (Eq. (36)) must be considered along with the Navier-Stokes equations of fluid momentum (Eq. (37)) and the flow continuity equation (Eq. (38).

Where ρ is the density, v is the velocity vector, Q is mass source, S is the viscous stress tensor, p the pressure, b is the body force and [M], [C], [K] are the mass, damping, stiffness matrices respectively. Combining the Navier-Stokes and the continuity equations, the acoustic wave equation can be written as

where μ is the dynamic viscosity and ρ0 is the mean fluid density.

The discretized structural equation (Eq. (36)) and the acoustic wave equation (Eq. (40)) must be considered simultaneously at the FSI interface. So it is convenient writing the equation in a matrix form. The finite element formulation is obtained by testing wave equation (Eq. (39)) using the Galerkin procedure [35]. Equation (39) is multiplied by testing function w and integrated over the volume of the domain [36] which yields the following:

where dv is the volume differential of acoustic domain (Ωf), ds is the surface differential of acoustic domain boundary (Γf) and \( \widehat{n} \) is the normal unit vector to the boundary.

From the equation of momentum conservation, the normal acceleration of the fluid, expressed in terms of the normal displacement, is given

Substituting Eq. (41) into Eq. (40) yields the acoustic wave Eq. (39) and can be expressed as follows:

The finite element approximating shape functions for the spatial variation of the pressure and displacement components are given by:

with {N} is the element shape function for pressure, {N'} is the element shape function for displacement and {p}, {u} are the nodal pressure and displacements vectors.

Using such formulation into the Eq. (42), the finite element statement of the wave (Eq. (39)) is expressed in matrix notation as following:

Where

- [Mf]:

-

\( {\overline{\rho}}_0{\iiint}_{\varOmega_f}\frac{1}{\rho_0{c}^2}\left\{N\right\}{\left\{N\right\}}^T dv \) is the acoustic fluid mass matrix

- [Cf]:

-

\( {\overline{\rho}}_0{\iiint}_{\varOmega_f}\frac{4\mu }{\rho_0^2{c}^2}{\left[\nabla N\right]}^T\left[\nabla N\right] dv \) is the acoustic fluid damping matrix

- [Kf]:

-

\( {\overline{\rho}}_0{\iiint}_{\varOmega_f}\frac{1}{\rho_0}{\left[\nabla N\right]}^T\left[\nabla N\right] dv \) is the fluid stiffness matrix

- [R]T:

-

\( {\iint}_{\varOmega_f}\left\{N\right\}{\left\{n\right\}}^T{\left\{{N}^{\hbox{'}}\right\}}^T ds \) is the acoustic fluid boundary matrix

- [ff]:

-

\( {\overline{\rho}}_0{\iiint}_{\varOmega_f}\frac{1}{\rho_0{c}^2}\left\{N\right\}{\left\{N\right\}}^T dv\left\{\dot{q}\right\}+{\overline{\rho}}_0{\iiint}_{\varOmega_f}\frac{4\mu }{\rho_0^2{c}^2}{\left[\nabla N\right]}^T\left[\nabla N\right] dv\left\{q\right\} \) is the acoustic fluid load with \( {\overline{\rho}}_0 \) the acoustic fluid mass density constant.

So the acoustic and structural matrices are coupled for fluid-structure interaction

where the subscript “s” and “f” represent the structural and fluid parts respectively.

3.4 Numerical Simulation Results

In order to validate the numerical models two different materials were considered of which the mechanical properties are well known [37]: a thermoplastic polymer (Polypropylene) and a unidirectional carbon-epoxy composite. For the polypropylene isotropic mechanical properties were considered. Regarding the composite, the matrix was considered to be isotropic, while the anisotropic material parameters for the fiber been applied [22]. The material properties are summarized in Tables 1 and 2.

A RVE with a cross section of 0.014–0.009 mm was built. For the epoxy-carbon composite, the carbon fibers were included. In particular a RVE with a hexagonal distribution of fiber was modelled. The fibers presented a diameter of 7.0 μm and a fiber volume fraction of 0.6 (Fig. 4). Symmetric and periodic boundary conditions in y and x coordinates, according to the local reference system of Fig. 4 must be applied in order to guaranty the periodicity of the microstructural strain tensor (\( {\varepsilon}_{ij}^{\ast } \)).

Regarding the static-structural analysis, a unidirectional tension loading was applied in z direction to estimate the out of plane (E3) elastic modulus. The mesh was fine enough to accurately represent the geometry of the reinforced fibers. Under the prescribed loading condition, the maximum tensile stress on the RVE and the relative strain status in the z direction were used to estimate the out of plane elastic modulus according to Hooke’s law (Eq. (35)). The simulation result in terms of tensional stress (σ3) and strain (ε3) for both materials are shown in Figs. 5 and 6.

Regarding the coupled acoustic-structural analysis the implemented FE model is shown in Fig. 7. The fluid volume into the tube was modelled as an acoustic body. Radiation boundary conditions were used at the input plane of the fluid domain, therefore acoustic waves normal to the boundary will be absorbed and not reflected into the acoustic domain. The acoustic load was applied in the same input plane and modelled using an acoustic mass source. On the other end of the acoustic body, the previous described RVEs were placed as samples and fluid-structure boundary conditions were applied. In order to avoid any translation of the sample a fixed support boundary conditions was applied on the external surface of the test sample. Finally, a coupled acoustic-structural harmonic analysis was set up to measure the pressure profile in two different planes into the fluid volume, according to constrains of Eq. (1) and Eq. (2).

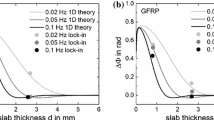

Starting from the acquired pressure time histories during the simulation, the reflection coefficient of the RVE can be extracted following the transfer function method, and then the acoustic impedance of the RVE can be estimated (Figs. 8 and 9) and the proposed method was applied in the post-processing of data to estimate the elastic modulus.

The results in terms of elastic modulus estimated by the proposed method and the tensile testing simulation compared with the elastic properties declared by the materials datasheet are reported in Table 3.

The results obtained from the numerical simulation both static-structural and acoustic-structural analysis are in good agreement with the elastic properties declared by the data-sheet of the relative materials. The proposed approach produced good results for isotropic (polypropylene) and orthotropic (epoxy-carbon composite) materials. The results from the acoustic-structural analysis match the results obtained with the static-structural model which simulate the standard tensile tests, commonly used for the elastic characterization of materials. Therefore, it was shown that using a standard impedance tube test rig both material acoustic characterization and elastic property evaluation of materials can be achieved.

4 Experimental Measurements Campaign

Here the results of an experimental measurement campaign are reported.

Different materials were tested and the proposed method was used to estimate the elastic modulus. In particular, two types of materials (foam and composite) were used to demonstrate the ability of the method to evaluate the Young’s Modulus of soft porous isotropic materials and out of plane Young’s Modulus of hard complex anisotropic materials.

The estimated elastic modulus were compared with those measured by standard testing methods. Regarding the composite samples the ultrasound time of flight (according to ASTM E 494 [38]) was used while for the foam sample, where such method produces inaccurate results because of the scattering of the longitudinal wave through the holes, a tensile test was used (according to ASTM D 3574 [39]).

4.1 Experimental Setup

Four samples was tested in the present measurement campaign.

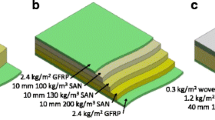

The tested materials include two acoustic soft foams with different densities (Foam 1 (ρ = 20 kg/m3) – Foam 2 (ρ = 25 kg/m3)), and two composites. The composite materials consist of epoxy resin (HexFlow RTM 6) reinforced by carbon fibre (HexForce Carbon Fabrics G1157) (sample 1) and Vynilester reinforced by glass fibre (sample 2).

The test rig used in the present work was the standard two microphones impedance tube described in the ASTM standard [14]. Such equipment is normally used for the measurement of the acoustic properties of porous and fibre materials.

When testing elastic properties of thermoplastic, polymer or composite materials within the test rig, there is potential for critical errors to occur. These errors are generally related to the phase and amplitude mismatch between the microphone measurements and attenuation of the tube walls associated to viscous thermal losses. In this case, these materials behave as acoustically rigid and the reflection coefficient is normally greater than 0.98–0.99, thus limiting the accuracy of the measurement. As the elastic properties are a function of the longitudinal propagation speed in the material which is strictly related to the reflection coefficient, the measurement of such coefficient must as accurate as possible.

A calibration procedure was applied to take into account the phase mismatch and the viscous thermal losses at the walls of the tube in order to increase the accuracy of the experimental measurements.

Cylindrical samples with a diameter of 50.8 mm were tested in an aluminium impedance tube with an internal diameter of 50.8 mm, so the experimental results are confined to the working frequency range (250–3800 Hz). A loudspeaker at one end of the tube was used to generate a broadband signal; in particular the samples were excited by a 3 s sine-sweep in the considered working frequency range. In addition, the amplitude-phase mismatch of the microphones measurements and the thermal-viscous losses were compensated according to the following proposed calibration procedure. Figure 10 shows the calibration effect on the measured reflection coefficient. The effect of using no correction data is to underestimate the reflection coefficient which lead to a under estimation of the acoustic impedance. At low frequencies the uncalibrated reflection coefficient estimation error was over 3%, a critical error for high reflective materials such as composites and polymeric materials.

The sample placing into the tube were done carefully in order to fit the sample itself with the internal wall of the tube. Any relative moving of the sample with the tube and any leakage must be avoid. The downstream section of the tube consisted of a hard-back termination attached to the downstream surface of the sample.

The two upstream measurement position were spaced of 30 mm, the second microphone position were separated by a 140 mm from the incident surface of the sample and the first microphone position were placed 330 mm from the speaker in order to guarantee the completely development of the standing plane wave into the tube.

Regarding the tensile testing carried out on the foam samples (Foam 1 and Foam 2) a dog bone shaped sample was used (refer to Fig. 11) with the material elastic modulus determined from measured stress-strain curves.

For the ultrasound time of flight measurements an ultrasonic pulse was sent which propagates through the sample with a certain longitudinal sound speed. Measuring the time between the front wall and back wall echo of the samples, the time of flight was estimated. Moreover, since the sample thickness is known, the longitudinal sound wave into the material can be calculated and used to evaluate the elastic modulus of the tested sample.

4.2 Experimental Results

Since the considered test rig is designed to guarantee a plane standing wave, the hypothesis of normal incident at the fluid-sample interface is fulfilled and longitudinal sound wave will propagated into the sample, thus estimation of the out of plane elastic properties is possible.

The calibrated sound pressures measured at two microphone positions were used to estimate the reflection coefficient and the acoustic impedance of the samples using the Transfer Function Method.

To reduce the effect of errors related to mounting the samples, material variability and the uncertainty of experimental measurements, five different measurements were performed for each sample. The results were consistent in terms of the reflection coefficient and elastic modulus. Moreover, since the tests were performed under plane wave conditions and only longitudinal waves propagate through the sample, the out of plane elastic properties are a function of the fibre volume fraction and not a function of fibre orientation.

The measured reflection coefficient and the relative acoustic impedance for the tested materials are shown in Figs. 12, 13, 14 and 15.

Moreover in Fig. 16 are shown the stress-strain curves measured during the tensile testing on the foam sample (Foam 1 and Foam 2).

Finally, the initial pulse and the back wall echo measured for both composite samples (Sample 1 and Sample 2) are shown in Fig. 17.

In Table 4 the elastic properties of the tested samples were estimated with the proposed method and compared with the relative elastic properties estimated with the commonly used methods.

Considering the acoustic soft foam the results in terms of elastic modulus estimated with the proposed method match with the elastic properties estimated by tensile tests with errors of under 8% for the Foam 1 and under 2% for Foam 2. It is clear that, the random distribution of porosity within the foam, allows for it to be considered isotropic.

When composite materials were tested, the results are always in good agreement with the results obtained with the time of flight approach both in terms of longitudinal sound speed and elastic modulus, but in this case the measurement uncertainties lead to error of 12% and 6% on the elastic modulus and 4% and 3% on the longitudinal speed respectively for the epoxy-carbon composite and vynilester-glass composite. In this case the mismatch of the results are associated with thermal-viscous losses through the impedance tube and to the amplitude-phase mismatch of the microphones. Reduced reflection coefficient accuracy occurs with highly reflective materials leading to a reduction in the accuracy of the estimated elastic properties (as explained in the previous section).

5 Conclusions

This paper proposes a method for the estimation of the elastic properties of porous, polymeric and composite materials using sound wave by measuring the reflection coefficient and the acoustic impedance in an impedance tube. The procedure described is based on the Transfer Function Method that derives information about the materials reflection coefficient. Under such hypothesis, the reflection coefficient is a function of the longitudinal speed of sound, of the acoustic impedance and as a consequence and the elastic properties of the material. A procedure was proposed to reduce the errors and the uncertainties on the measurements for high acoustic reflective materials such as composite or polymeric materials. The method was first tested in-silico using representative volume element and then experimentally verified.

The proposed approach would allow for the estimation of the elastic modulus for materials where ultrasound time of flight cannot be applied, for example porous materials. An error of only 2% is achieved when comparing the elastic modulus results with those obtained by destructive test (tensile testing).

For the first time, it was shown that using sound waves the elastic properties of composite materials can be evaluated where no standard test is available. In this case, the measured elastic modulus represents the out of plane elastic modulus (E3) and measurement errors were around 3% for the longitudinal speed of sound and 10% for the elastic modulus with respect to ultrasonic testing.

The proposed methods is a reliable, effective and quick non-destructive method for the Elastic Modulus evaluation providing clear advantage over traditional techniques such as standard destructive methods or ultrasound time of flight measurements.

References

Petersen, K.E.: Silicon as a mechanical material. Proc. IEEE. 70, 420–457 (1982)

Oliver, W.C., Pharr, G.M.: Measurement of hardness and elastic modulus by instrumented indentation: advances in understanding and refinements to methodology. J. Mater. Res. 19, 3–20 (2004)

Oliver, W.C., Pharr, G.M.: An improved technique for determining hardness and elastic modulus using load and displacement sensing indentation experiments. J. Mater. Res. 7, 1564–1583 (1992)

Lang, S.B.: Ultrasonic method for measuring elastic coefficients of bone and results on fresh and dried bovine bones. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. BME-17, 101–105 (1970)

Ashman, R., Cowin, S., Van Buskirk, W., Rice, J.: A continuous wave technique for the measurement of the elastic properties of cortical bone. J. Biomech. 17, 349–361 (1984)

Rho, J.Y., Ashman, R.B., Turner, C.H.: Young's modulus of trabecular and cortical bone material: ultrasonic and microtensile measurements. J. Biomech. 26, 111–119 (1993)

Jones, M.G., Stiede, P.E.: Comparison of methods for determining specific acoustic impedance. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 101, 2694–2704 (1997)

Dalmont, J.-P.: Acoustic impedance measurement, part I: a review. J. Sound Vib. 243, 427–439 (2001)

Kumar, A., Kumar, B., Kumar, Y.: A novel method to determine the acoustic impedance of membrane material. Ultrasonics. 35, 53–56 (1997)

Song, B.H., Bolton, J.S.: A transfer-matrix approach for estimating the characteristic impedance and wave numbers of limp and rigid porous materials. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 107, 1131–1152 (2000)

Doutres, O., Salissou, Y., Atalla, N., Panneton, R.: Evaluation of the acoustic and non-acoustic properties of sound absorbing materials using a three-microphone impedance tube. Appl. Acoust. 71, 506–509 (2010)

Buchaillot, L., Farnault, E., Hoummady, M., Fujita, H.: Silicon nitride thin films Young's modulus determination by an optical non destructive method. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 36, L794–L797 (1997)

França, D., Blouin, A.: All-optical measurement of in-plane and out-of-plane Young's modulus and Poisson's ratio in silicon wafers by means of vibration modes. Meas. Sci. Technol. 15, 859–868 (2004)

ASTM 1050, “Standard test method for impedance and absorption of acoustical materials using a tube, two microphones and a digital frequency analysis system”, Astm International, (2012)

Chung, J.Y., Blaser, D.A.: Transfer function method of measuring in-duct acoustic properties. I. Theory. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 68, 907–913 (1980)

Chung, J.Y., Blaser, D.A.: Transfer function method of measuring in-duct acoustic properties. II. Experiment. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 68, 914–921 (1980)

J. Han, D.W. Herrin, A. F. Seybert, “Accurate measurement of small absorption coefficient”, Sae International, 01–2224 (2007)

ISO 10534-2/2, “Acoustic-Determination of sound absorption coefficient and impedance in impedance tubes – Part 2: Transfer-function method”

J. David, N. Cheeke, “Fundamentals and Applications of Ultrasonic Wave”, CRC PRESS, (2002)

A. B. Wood, “A Textbook of Sound”, G. Bell and Sons Ltd, (1964)

D.T. Blackstock, “Fundamentals of Physical Acoustics”, John Wiley & Sons, (2000)

Sun, W., Guan, Z., Li, Z., Zhang, M., Huang, Y.: Compressive failure analysis of unidirectional carbon/epoxy composite based on micro-mechanical models. Chin. J. Aeronaut. 30, 1907–1918 (2017)

Chen, X.L., Liu, Y.J. Square representative volume elements for evaluating the effective material properties of carbon nanotube-based composite. Comput. Mater. Sci. 29, 1–11 (2004)

Odegard, G.M.: Costitutive modelling of piezoelectric polymer composite. Acta Mater. 52, 5315–5330 (2004)

Kari, S., Berger, H., Rodriguez-Ramos, R., Gabbert, U.: Computational evaluation of effective material properties of composite reinforced by randomly distributed spherical particles. Compos. Struct. 77, 223–231 (2007)

Hollister, S.J., Kikuchi, N.: A comparison of homogenization and standard mechanics analysis for periodic porous composites. Comput. Mech. 10, 73–95 (1992)

Iorga, L., Pan, Y., Pelegri, A.: Numerical characterization of material elastic properties for random fiber composites. J. Mech. Mater. Struct. 3, 1279–1298 (2008)

Pelissou, C., Baccou, J., Monerie, Y., Perales, F.: Determination of the size of the representative volume element for random quasi-brittle composite. Int. J. Solids Struct. 46, 2842–2855 (2009)

Babu, K.P., Mohite, P.M., Upadhyay, C.S.: Development of an RVE and its stiffness predictions based on mathematical homogenization theory for short fiber composites. Int. J. Solids Struct. 130-131, 80–104 (2018)

Xia, Z., Zhang, Y., Ellyin, F.: A unified periodical boundary conditions for representative volume elements of composites and applications. Int. J. Solids Struct. 40, 1907–1921 (2003)

Smit, R.J.M., Brekelmans, W.A.M., Meijer, H.E.H.: Prediction of the mechanical behaviour of nonlinear heterogeneous system by multi-level finite element modelling. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 155, 181–192 (1998)

Segurado, J., Llorca, J.: A numerical approximation to the elastic properties of sphere-reinforced composites. Journal of the Mechanics and Physics of Solid. 50, 2107–2121 (2002)

Huet, C.: Application of variational concepts to size effects in elastic heterogeneous bodies. J. Mech. Phys. Solids. 8, 812–841 (1990)

Hazanov, S., Huet, C.: Order relationships for boundary condition effects in heterogeneous bodies smaller than the representative volume. J. Mech. Phys. Solids. 42, 1995–2011 (1994)

K. J. Bathe, “Finite Element Procedures”, Prentice-Hall, (1996)

O. C. Zienkiewicz, R. E. Newton. "Coupled Vibrations of a Structure Submerged in a Compressible Fluid", Procedings of the symposium on finite element techniques, (1969)

Soden, P.D., Hinton, M.J., Kaddour, A.S.: Lamina Properties. Lay-up configurations and loading conditions for a range of fibre-reinforced composite laminates. Compos. Sci. Technol. 58(7), 1011–1022 (1998)

ASTM E 494, “Standard practice for measuring ultrasonic velocity in materials”, Astm International, (2012)

ASTM D 3574, “Standard Test Method for Flexible Cellular Materials – Slab, Bonded, and Molded Urethane Foams ”, Astm International, (2012)

Acknowledgments

This paper has been funded by the EXTREME project of the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement No. 636549.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Bucciarelli, F., Malfense Fierro, G.P., Zarrelli, M. et al. A Non-Destructive Method for Evaluation of the Out of Plane Elastic Modulus of Porous and Composite Materials. Appl Compos Mater 26, 871–896 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10443-018-9754-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10443-018-9754-5