Abstract

Purpose

To investigate the technical feasibility, safety and clinical outcomes of coil-assisted retrograde transvenous obliteration II (CARTO-II) for gastric varices (GV).

Materials and Methods

Thirty-six consecutive patients who had undergone CARTO-II between June 2016 and April 2018 were included in the study. In the CARTO procedure, coil embolization of the drainage vein is performed “before” injection of the sclerosant to replace the use of balloon catheter. In the CARTO-II procedure, coil embolization of the drainage vein was performed “after” injection of the sclerosant to prevent migration of the sclerosant. CARTO-II was performed with ethanolamine oleate iopamidol, and the balloon catheter was immediately removed after coil placement. Technical and clinical success rates, number of coils used, presence or absence of severe complications, timing of the procedure, and rate of GV recurrence after the procedure were analyzed retrospectively.

Results

In all patients, GV sclerosis, coil placement and removal of the balloon catheter were successfully completed. The technical success rate was 100%. No patients experienced severe complications such as coil migration or pulmonary embolization. The mean number of metallic coils used per procedure was 3.36. Mean length of the procedure was 132.8 min. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography after CARTO-II confirmed complete variceal thrombosis in all cases. The recurrence rate of GV during follow-up was 2.8% (mean follow-up, 207 days).

Conclusion

CARTO-II was feasible and safe and could be performed relatively quickly. The number of coils used and the rate of GV recurrence were both low. CARTO-II may have an important role to play in the management of GV.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Balloon-occluded retrograde transvenous obliteration (BRTO) is an endovascular procedure that was originally developed by Kanagawa et al. to treat gastric varices (GV) [3]. The effectiveness of BRTO is now well established, with the technique offering a high clinical success rate [7].

One of the major drawbacks of conventional BRTO is that BRTO is a time-consuming procedure. Although sclerosis can be obtained within 3 h after injection of the sclerosant, an inflated balloon catheter is left in place for 4–24 h in patients at risk of coil migration or sclerosant leakage. There are many reports regarding BRTO being performed in this manner [6, 8, 9, 13, 15, 16]. The length of this procedure potentially carries a risk of deep venous thrombosis, pulmonary embolization, and balloon rupture in addition to the burden on the patient in terms of discomfort and limitations on movement. To overcome this drawback, the new strategy of plug-assisted retrograde transvenous obliteration (PATRO) was developed [2]. Although this procedure is associated with a relatively high rate of GV recurrence, procedure time was shortened because immediate removal of the catheter is achievable with the Amplatzer vascular plug. Lee et al. then introduced coil-assisted retrograde transvenous obliteration (CARTO) [10], using coils instead of an inflated balloon catheter. This procedure can be performed in patients with smaller and larger shunts because of the availability of a wide variety of coil diameters. In this procedure, two catheters were inserted into the drainage vein and the narrowest portion of the gastro-renal (GR) shunt. After coil embolization via the catheter into the GR shunt, gelfoam slurry or sodium tetradecyl sulfate (STS) was injected through the microcatheter in the GV. Here, we report on our experience with a modified CARTO procedure. We follow a standard BRTO with a balloon catheter, deploying multiple coils through the balloon catheter to prevent migration of the sclerosant. After the coils are placed, the occluding balloon can be removed. This technique was introduced as CARTO-II by Kim et al. [4]. In the review report, only one case was shown in a figure regarding this approach. The purpose of this study was thus to confirm the utility of CARTO-II by evaluating the feasibility, safety and clinical outcomes.

Materials and Methods

Patients and Treatment Criteria

This retrospective study was approved by our institutional review board. The study was initially designed to include 41 consecutive patients who had undergone BRTO for GV in our institute between June 2016 and April 2018. Thirty-six patients were finally enrolled, after excluding five patients who underwent emergent BRTO (n = 3), were found to be ineligible for BRTO due to high wedge pressure of the hepatic vein (45 mmHg) after temporary occlusion of the GR shunt (n = 1), or who did not undergo BRTO due to visualization of apparent portopulmonary vein anastomosis (PPVA) during the procedure (n = 1). Endoscopic findings of GV were classified according to the criteria proposed by the Japanese Society for Portal Hypertension [14]. Briefly, the form of the GV was classified as: F1, straight, small-caliber varices; F2, moderately enlarged, beady varices; or F3, markedly enlarged, nodular, or tumor-shaped varices. Treatment was performed for GV that were endoscopically categorized as F2 or more, showed positive results for the red color sign, and were progressing.

Procedure

With the patient in a supine position and locally anesthetized, BRTO was performed by transvenously inserting a balloon catheter into the main draining vein, which is the GR shunt, the left inferior phrenic vein (IPV), or the pericardiacophrenic vein (PCV). The basic system involved introduction of a catheter into the right femoral vein with a 9-Fr/5-Fr double coaxial balloon catheter system (CANDIS, Medikit, Tokyo, Japan) or 5-Fr balloon catheter (Selecon MP cobra catheter; Terumo Clinical Supply, Gifu, Japan) for GR shunt access, introduction into the right femoral vein or left internal jugular vein with microballoon catheter (Pinnacle Blue, Tokai Medical, Kasugai, Japan, or Masamune, Fuji Systems, Tokyo, Japan) for IPV shunt or PCV access. Balloon-occluded retrograde transvenous venography (BRTV) was performed to classify patients according to Hirota’s criteria. All patients were confirmed to be free of PPVA by BRTV. Before embolization of GV, wedge pressure of the right hepatic vein was measured through the additional balloon catheter inserted into the right hepatic vein to confirm the portal pressure. Patients underwent treatment with 5% ethanolamine oleate iopamidol (EOI) [10% ethanolamine oleate (Oldamin, ASKA Pharmaceutical, Osaka, Japan) mixed with the same volume of nonionic contrast medium (iopamidol 300 mg I/mL, Iopamiron 300, Bayer Schering Pharma, Osaka, Japan)] with or without gelatin sponge particles. At least 10 min after finishing EOI injection, coil embolization of the drainage vein was performed through the balloon catheter or microcatheter inserted in the balloon catheter (Fig. 1). At least 30 min after EOI injection, the balloon catheter and sheath were removed. To prevent renal dysfunction caused by EOI-induced hemolysis, drip infusion of 4000 U of haptoglobin was performed during injection of the 5% EOI.

Schema of CARTO-II. A Balloon catheter is inserted into the drainage vein of gastric varices (GV). Balloon-occluded retrograde transvenous venography is performed in the same manner as conventional balloon-occluded retrograde transvenous obliteration. B Sclerosant [ethanolamine oleate iopamidol (EOI)] is injected into the GV. C Metallic coils are inserted into the drainage vein via balloon catheter after injection of sclerosant. D At least 30 min after injection of sclerosant, balloon catheter is removed. IVC inferior vena cava, RV renal vein

Evaluation of the Procedure

In computed tomography (CT) before the procedure, maximum short diameter of the drainage vein was measured. Technical success was defined as achievement of both stagnation of sclerosants in GV on unenhanced CT or cone-beam CT (CBCT) immediately after the procedure and immediate removal of the balloon catheter after coil embolization. The length of the procedure was evaluated. The length of the procedure was defined as the interval from entering the angiography room to leaving the room. All patients underwent contrast-enhanced multidetector row CT (CECT) of the chest–abdomen–pelvis 4 days after the procedure. The same scan was also used to check for pulmonary or venous complications, portal embolism or major complications. Sclerosant-related adverse effects such as disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC), acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), and worsening of renal function were also clinically evaluated. Patients were followed-up and endoscopy was performed every 3–6 month after BRTO. If anemia worsened or hematemesis occurred during observation, endoscopy was performed in a timely manner. During patient follow-up, recurrence of GV was defined as enlargement of GV apparent on endoscopy. Rates of recurrence for GV after BRTO were also analyzed. Clinical success was defined as absence of recurrence after BRTO.

Results

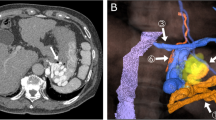

Patient characteristics are listed in Table 1. Coil embolization of the drainage vein and removal of the balloon catheter were achieved in all 36 patients (Fig. 2). The main drainage vein was the GR shunt in 32 patients, the IPV in three patients, and the PCV in one patient (Table 2, Fig. 3). Mean dose of 5% EOI used was 13.5 mL (range, 4–40 mL). Mean number of metallic coils used per procedure was 3.36. The procedure used many kinds of metallic coils, such as 0.035″ coils (AZUR CX35, Terumo Clinical Supply, Tokyo, Japan, or Interlock 35, Boston Scientific, Massachusetts), 0.018″–0.021″ coils (Penumbra RubyTM Coil system, Penumbra, Alameda, California, or Target XL, Stryker, Tokyo, Japan, or AZUR CX, Terumo Clinical Supply), or pushable coils (C-stopper coil, PIOLAX, Tokyo, Japan). In all patients, blood flow stagnation was seen on venograms obtained immediately after final balloon deflation (technical success rate, 100%). Mean length of the procedure was 132.8 min. This time included measurement of wedge pressure of the hepatic vein. On CECT performed after BRTO (day 4 ± 1 after the procedure), complete variceal thrombosis was confirmed in all cases. No severe complications, such as liver failure, renal failure, DIC, or ARDS, were observed. One of the 36 patients experienced recurrence of varices during follow-up (mean follow-up period for varix observation, 168 days; range, 2–580 days). The clinical success rate was 97.2% (35/36). All patients survived follow-up (mean overall follow-up period, 207 days; range, 3–675 days).

A 60-year-old man with a gastric varix. A The varix is revealed on contrast-enhanced computed tomography along the fundus (arrow). B Balloon-occluded retrograde transvenous venography (BRTV) was performed. Gastric varix was identified (arrow). C Sclerosant [ethanolamine oleate iopamidol (EOI)] is injected into the varix (arrow). D After injection of sclerosant, metallic coils (AZUR CX35 13 mm × 24 cm, three of 10 mm × 19 cm, 8 mm × 24 cm; Terumo Clinical Supply, Tokyo, Japan) are inserted into the drainage vein via balloon catheter (CANDIS; Medikit, Tokyo, Japan). After coiling, the balloon catheter is removed

A 65-year-old man with gastric varix. A The varix is revealed on contrast-enhanced computed tomography along the fundus (arrow). B On volume-rendered contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT), the pericardiacophrenic vein is identified as a drainage vein (arrow). The varix is also revealed on CT (arrowhead). C After insertion of a microballoon catheter into the pericardiacophrenic vein, sclerosant [ethanolamine oleate iopamidol (EOI)] is injected into the varix (arrow). D After injection of sclerosant, metallic coils (two Target XL 10 mm × 40 cm; Stryker, Tokyo, Japan) are inserted into the drainage vein via microballoon catheter (Masamune; Fuji Systems, Tokyo, Japan). After coiling, the microballoon catheter is removed

Discussion

In this study, CARTO-II was performed in all 36 patients (technical success rate, 100%; clinical success rate, 97.2%) with a relatively short operation time (132.8 min). No severe complications were observed. This technique was thus considered safe and feasible.

In this CARTO-II procedure, coil placement was achieved in all cases. Maximum short diameter of the drainage vein was 16 mm. Because large coils > 30 mm are available and the narrowest portion of the GR shunt was thought to be less than the maximum short diameter of the coils, this technique could be applied to almost all varices. In PARTO, the maximum diameter of available Amplatzer vascular plugs was 22 mm. This procedure cannot be applied for GV with a large shunt. Moreover, CARTO-II was performed via the IPV and PCV. Although these veins have not been frequently reported as drainage veins, BRTO through these veins has been described [1]. However, these veins are basically narrow compared to the GR shunt, and inserting a sheath to use an Amplatzer vascular plug is difficult. Because coil placement in CARTO-II can be performed through a microcatheter, CARTO-II could be performed from various kinds of drainage veins, even intercostal veins [12]. This is considered as one advantage of the CARTO-II technique.

The mean number of coils used in this CARTO-II was 3.36 (range, 1–7). In the original CARTO procedure, the number of coils used was 11.1 (range, 5–22) [10]. CARTO-II is considered much cheaper than CARTO. The reason for the lower number of coils used is the fact that total occlusion is not required in CARTO-II. In CARTO, sclerosants are injected after complete occlusion of the drainage vein, whereas CARTO-II places coils to prevent migration of coagulated blood and thus avoid pulmonary embolization. Sclerosis of GV was completed through the balloon catheter before coil embolization. This use of a relatively lower number of coils shortens the procedure time and reduces costs. Mean procedure length (time from entering the angiography room to leaving the room) was 132.8 min (2.2 h) in this study, compared to 2.82 h for CARTO [10]. This time included the time to ready the patient for the procedure in the room and the time to measure wedge pressure (at least 15 min). Mean procedure time for CARTO-II was under 2 h. Generally, procedure length appears shorter for CARTO-II than for CARTO. One reason for this short procedure length was the lack of any need to wait for complete occlusion before injecting sclerosants. CARTO-II can thus be considered less time-consuming and expensive than CARTO.

Many kinds of sclerosant are available, such as EOI, gelfoam slurry, STS, or lauromacrogol used in BRTO for GV. With CARTO-II, the only difference from conventional BRTO using sclerosant is the use of coils after sclerosis. This technique does not place specific limits on the type of sclerosant. In the PARTO procedure with gelfoam slurry, the recurrence rate was initially relatively high (32.8% at 1 year) [5]. A modified method with gelfoam followed by STS has shown better outcomes approaching a 0% of recurrence rate [4], In a study of conventional BRTO using STS only, 1-year recurrence rate was reported to be 1.3%. In a study of conventional BRTO using lauromacrogol, complete obliteration of GVs was confirmed in all 31 patients (100%) on CT [11]. In a prospective study of conventional BRTO using EOI, the rate of complete thrombosis of GV according to CECT on day 90 was 93.0% (40 of 43 patients) [6]. In this report, the complete regression rate of GV according to endoscopy on day 90 was 97.2%. Theoretically, the clinical outcomes should be similar to those of conventional BRTO with EOI.

First limitation of this study was that the patient cohort was relatively small. A larger study is needed in the future. Second limitation of this study was the retrospective design. Third limitation of this study was that CARTO-II study did not conduct direct comparisons with other techniques such as PARTO or CARTO.

Conclusion

The present study found that CARTO-II was feasible and safe and could be performed in a relatively short time. The number of coils used was low, as was the rate of GV recurrence. CARTO-II may have an important role to play in the management of GV.

References

Araki T, Hori M, Motosugi U, et al. Can balloon-occluded retrograde transvenous obliteration be performed for gastric varices without gastrorenal shunts? J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2010;21(5):663–70.

Gwon DI, Ko GY, Yoon HK, et al. Gastric varices and hepatic encephalopathy: treatment with vascular plug and gelatin sponge-assisted retrograde transvenous obliteration—a primary report. Radiology. 2013;268(1):281–7.

Kanagawa H, Mima S, Kouyama H, Gotoh K, Uchida T, Okuda K. Treatment of gastric fundal varices by balloon-occluded retrograde transvenous obliteration. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1996;11(1):51–8.

Kim DJ, Darcy MD, Mani NB, et al. Modified balloon-occluded retrograde transvenous obliteration (BRTO) techniques for the treatment of gastric varices: vascular plug-assisted retrograde transvenous obliteration (PARTO)/coil-assisted retrograde transvenous obliteration (CARTO)/balloon-occluded antegrade transvenous obliteration (BATO). Cardiovasc Interv Radiol. 2018;41(6):835–47.

Kim YH, Kim CS, Kang UR, Kim SH, Kim JH. Comparison of balloon-occluded retrograde transvenous obliteration (BRTO) using ethanolamine oleate (EO), BRTO using sodium tetradecyl sulfate (STS) foam and vascular plug-assisted retrograde transvenous obliteration (PARTO). Cardiovasc Interv Radiol. 2016;39(6):840–6.

Kobayakawa M, Kokubu S, Hirota S, et al. Short-term safety and efficacy of balloon-occluded retrograde transvenous obliteration using ethanolamine oleate: results of a prospective, multicenter single-arm trial. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2017;28(8):1108–15.

Kobayakawa M, Ohnishi S, Suzuki H. Recent development of balloon-occluded retrograde transvenous obliteration. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;34(3):495–500.

Kobayashi K, Maruyama H, Kiyono S, et al. Portal response related to shunt occlusion by balloon-occluded retrograde transvenous obliteration may determine the prognosis of cirrhosis. Hepatol Res. 2016;46(13):1321–9.

Kumamoto M, Toyonaga A, Inoue H, et al. Long-term results of balloon-occluded retrograde transvenous obliteration for gastric fundal varices: hepatic deterioration links to portosystemic shunt syndrome. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;25(6):1129–35.

Lee EW, Saab S, Gomes AS, et al. Coil-assisted retrograde transvenous obliteration (CARTO) for the treatment of portal hypertensive variceal bleeding: preliminary results. Clin Transl Gastroenterol. 2014;5:e61.

Luo X, Ma H, Yu J, Zhao Y, Wang X, Yang L. Efficacy and safety of balloon-occluded retrograde transvenous obliteration of gastric varices with lauromacrogol foam sclerotherapy: initial experience. Abdom Radiol. 2018;43(7):1820–4.

Minamiguchi H, Kawai N, Sato M, et al. Balloon-occluded retrograde transvenous obliteration for gastric varices via the intercostal vein. World J Radiol. 2012;4(3):121–5.

Miyamoto Y, Oho K, Kumamoto M, Toyonaga A, Sata M. Balloon-occluded retrograde transvenous obliteration improves liver function in patients with cirrhosis and portal hypertension. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2003;18(8):934–42.

Tajiri T, Yoshida H, Obara K, et al. General rules for recording endoscopic findings of esophagogastric varices (2nd edition). Dig Endosc. 2010;22(1):1–9.

Uehara H, Akahoshi T, Tomikawa M, et al. Prediction of improved liver function after balloon-occluded retrograde transvenous obliteration: relation to hepatic vein pressure gradient. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;27(1):137–41.

Yamamoto A, Nishida N, Morikawa H, et al. Prediction for improvement of liver function after balloon-occluded retrograde transvenous obliteration for gastric varices to manage portosystemic shunt syndrome. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2016;27(8):1160–7.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Human and Animal Rights

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

For this type of study, formal consent is not required.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Yamamoto, A., Jogo, A., Kageyama, K. et al. Utility of Coil-Assisted Retrograde Transvenous Obliteration II (CARTO-II) for the Treatment of Gastric Varices. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol 43, 565–571 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00270-019-02399-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00270-019-02399-z