Abstract

Dispersed colloidal particles that are set into systematic motion by a controlled external field constitute excellent model systems for studying structure formation far from equilibrium. Here we identify a unique demixing force that arises from repulsive interparticle interactions in driven binary colloids. The corresponding demixing force density is resolved in space and in time and it counteracts diffusive currents which arise due to gradients of the local mixing entropy. We construct a power functional approximation for overdamped Brownian dynamics that describes superadiabatic demixing as an antagonist to adiabatic mixing as originates from the free energy. We apply the theory to colloidal lane formation. The theoretical results are in excellent agreement with our Brownian dynamics computer simulation results for adiabatic, structural, drag and viscous forces. Superadiabatic demixing allows to rationalize the emergence of mixed, laned and jammed states in the system.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The concept of mixing entropy in multi-component systems is profound for our understanding and quantitative description of complex systems. In equilibrium, mixing entropy can overcome strong energetic repulsion that arises due to internal interactions between the constituent particles. It is a driving mechanism, if not an antagonist, for a wide range of structuring and self-assembly phenomena1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12. The systems and phenomena where mixing entropy plays a crucial role cover a broad range, ranging from the fundaments of liquid state theory to specific applications.

Mixing entropy was shown to be relevant for the determination of the equation of state of binary mixtures of hard spheres1. It determines phase behavior, such as entropy-driven phase transitions of colloid-polymer mixtures2, liquid-liquid immiscibility in polymer solutions3, and the demixing transition in athermal mixtures of colloids and flexible self-excluding polymers4. For the liquid crystal physics displayed by anisotropic particles, mixing entropy plays a role for the isotropic-nematic-nematic phase separation for bidisperse rod-like particles5, and for rod-plate mixtures, where biaxiality competes with demixing6. Mixing entropy is relevant for percolation in binary and ternary mixtures of patchy colloids7, and for selectivity in spatially inhomogeneous binary fluid mixtures8.

Important technological applications where mixing entropy is relevant include the capacitive mixing for harvesting the free energy of solutions9, and in ‘blue energy’ from ion adsorption and electrode charging in sea and river water10. Although in nonequilibrium the situation is much less clear, gradients of position-resolved mixing entropy fields were shown to be relevant e.g., for the dynamics of liquid films with soluble surfactant11. Beyond the soft matter realm, mixing entropy is relevant for the stability of metallic alloys12.

Here, we identify and describe a competing effect that occurs in genuine nonequilibrium and that can counteract diffusive forces generated by the mixing entropy in a similar way that explicit interparticle repulsion does in equilibrium. We show that this effect is “superadiabatic” in character, i.e., it acts above all effects that can be understood on the basis of an equilibrium (“adiabatic”) reference state and its free energy. As we show, superadiabatic demixing is a genuine nonequilibrium effect and a corresponding unique superadiabatic force density distribution can be identified that acts spatially and temporally resolved in nonequilibrium systems. As both a relevant application and a demonstration of the concept we revisit the well-studied phenomenon of colloidal lane formation in oppositely driven binary mixtures, where for the first time we are able to rationalize quantitatively, on the basis of a physical model of the underlying superadiabatic effect, the emergence of nonequilibrium structure formation in this system.

Results

Lane formation

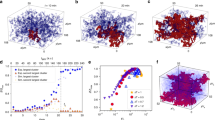

We show in Fig. 1 characteristic snapshots of a colloidal mixture of two species with repulsive interparticle interactions driven in opposite directions. At low driving, Fig. 1a, the diffusive forces generated by the entropy of mixing dominate and the system remains in a homogeneous state with both species flowing through each other. At high driving however the species segregate into two lanes, Fig. 1b. Lane formation constitutes a genuine nonequilibrium self-organization process that has attracted much interest in the literature since it occurs in strikingly different areas, ranging from colloidal systems13,14,15,16,17,18, plasmas19,20, and lattice models21, to different kinds of living systems, such as bacteria in channels22, ant trails23, and groups of pedestrians24. Laning has also been studied when the external driving directions of the two species are non-parallel to each other25, have high shear rates26, or other characteristics such as rotating magnetic field in channels, and periodic driving with different friction coefficients27,28,29. Studies were devoted to the influence of noise and of hydrodynamic interactions30,31, as well as the characteristics of the transition toward laning in two-dimensional systems32. Although the primary focus is on purely repulsive model systems, such as model suspensions of charged colloids, laning has also been shown to appear in systems governed by attractive33 and by dipolar34 interparticle interactions.

Particles of species 1 (orange) possess a positive buoyant mass, i.e., the external force acting on them is directed downwards. Particles of species 2 (blue) have a negative buoyant mass and hence upwards directed external force acting on them. The arrows indicate the direction of the different forces in the system. The color of the arrow shows the species on which the forces act, and its size indicates the relative magnitude of the force as compared to the other forces. At low external driving (a) the system is homogeneous. Forces only act in the flow \(\hat{{\bf{y}}}\)-direction. At high external driving (b) the system segregates into lanes. The forces acting in the gradient \(\hat{{\bf{x}}}\)-direction (diffusive, adiabatic, and structural) balance each other. The small white arrows indicate the direction of the velocity inside the lanes.

Physical mechanisms for laning were attributed to rectification of diffusion on the particle scale35. The pair correlation functions were considered to be the key observables to quantify the laning phenomenon36. Theoretical treatments have been scarce. Based on phenomenological versions of dynamical density functional theory Chakrabarti and coauthors14,15 obtained a dynamical instability as a steady-state bifurcation of the density field around the onset of structural inhomogeneity in the simulations. Poncet et al.36 used linearized stochastic density functional theory for the pair correlation functions. Kohl et al.37 used a microscopic approach, based on Kirkwood’s superposition approximation as a closure relation, to also calculate nonequilibrium pair correlations in strongly interacting driven binary mixtures. Wächtler et al.33 performed a stability analysis based on dynamical density functional theory.

Despite this progress, a systematic theoretical framework that would describe laning has not yet been formulated. Here, we present a comprehensive theory for driven binary mixtures that operates on the level of one-body correlation functions, such as (partial) density and current distributions. The general framework constitutes a closed theory, based on the power functional concept for mixtures38,39. We present an approximate form of the superadiabatic free power functional, which is a functional generator of the nonequilibrium force distributions. Crucially, we demonstrate that the superadiabatic demixing force fields are kinematic functionals, i.e., depend not only on the density, but also on the flow fields. The theory allows us to quantitatively describe the stability of lane formation.

Dynamical one-body description

Let the positions of N particles in d spatial dimensions be indicated by r1, …rN ≡ rN. We consider systems that are composed of different species, labeled by α. The set \({{\mathcal{N}}}_{\alpha }\) contains all particle indices i that belong to species α. The dynamics of the system are governed by the coupled Langevin equations for overdamped Brownian motion,

where γ is the friction constant against the implicit solvent (we consider γ to be the same for all particles), the overdot denotes a time derivative, ∇i indicates the derivative with respect to ri, u(rN) is the interparticle interaction potential, fext,i(r, t) is an external force field acting on particle i at position r at time t; here r is a generic position coordinate. Furthermore ξi(t) is a stochastic white noise force with vanishing mean, 〈ξi(t)〉 = 0, and auto-correlation given by

where the angles denote an average over the realizations of the noise, kB indicates the Boltzmann constant, T is absolute temperature, 1 is the d × d-unit matrix, and δ(⋅) is the Dirac delta distribution. In practice, we discretize the equations of motion, Eq. (1), with a finite time step Δt, and integrate in time using the Euler algorithm.

We define the one-body density and current distribution functions, respectively, for each species α as

where the angles denote an average both over the noise as before, but also over the set of initial states; the velocity of particle i is given by a symmetric time derivative, vi(t) = (ri(t + Δt) − ri(t − Δt)) ∕ (2Δt) (see e.g., appendix A of ref. 40 for the derivation). We obtain the microscopically resolved velocity profile of species α as the ratio

The continuity equation holds individually for each species,

where ∇ indicates the derivative with respect to r.

The one-body equation of motion translates the sum of all forces that act into local motion. The dynamics on the one-body level are specified by the (exact) force density balance relationship

where the three terms on the right hand side constitute the force densities due to thermal diffusion, internal interactions, and external influence. Due to the overdamped character of the dynamics, the sum of these forces directly induces a current, cf. the left hand side of Eq. (7). Here, the internal force density field arises from the interparticle interaction potential u(rN) and is defined via the average

Furthermore the external force field \({{\bf{f}}}_{{\rm{ext}}}^{\alpha }({\bf{r}},t)\) in Eq. (7) acts on particles of species α, hence the external force acting on particle \(i\in {{\mathcal{N}}}_{\alpha }\), as appearing in the Langevin equation, Eq. (1), is given by \({{\bf{f}}}_{{\rm{ext}},i}({{\bf{r}}}_{i},t)={{\bf{f}}}_{{\rm{ext}}}^{\alpha }({{\bf{r}}}_{i},t)\).

The internal one-body force density distributions can be split into adiabatic and superadiabatic one-body contributions38,39,41, according to

Here, the adiabatic force density distribution \({{\bf{F}}}_{{\rm{ad}}}^{\alpha }({\bf{r}},t)\) is defined as the internal force density that occurs in a corresponding “adiabatic” equilibrium system that is defined by having the same partial density distributions as the nonequilibrium system, \({\rho }_{\alpha }^{{\rm{ad}}}({\bf{r}})={\rho }_{\alpha }({\bf{r}},t)\), ∀α. The adiabatic force density is also defined by Eq. (8), but with the crucial alteration that the average is now taken over an equilibrium probability distribution (i.e., that of the adiabatic system). Here, the external “adiabatic” one-body potentials \({V}_{{\rm{ad}}}^{\alpha }({\bf{r}})\) act on species α in order to stabilize the given partial density distributions, via (conservative) force fields \(-\nabla {V}_{{\rm{ad}}}^{\alpha }({\bf{r}})\).

The superadiabatic force density distribution \({{\bf{F}}}_{\sup }^{\alpha }({\bf{r}},t)\) in Eq. (9) contains therefore all nonequilibrium effects which arise due to the presence of the flow in the system.

Dividing Eq. (7) by the partial density ρα and using Eqs. (5) and (9) we obtain the species-resolved force balance:

The total density profile ρ(r, t) and the total current distribution J(r, t) can be obtained, respectively, by summation of Eqs. (3) and (4) over all species, i.e.,

In analogy to the partial velocity, Eq. (5), the mean total velocity is then obtained as

Summing the species-resolved continuity equation, Eq. (6), over all species and using Eqs. (11) and (12) yields the total continuity relation as

Analogously, summing the species-resolved force density balance, Eq. (7), over all species yields the total force density balance,

where the total internal force density field is \({{\bf{F}}}_{{\rm{int}}}=\sum _{\alpha }{{\bf{F}}}_{{\rm{int}}}^{\alpha }\), with the force density \({{\bf{F}}}_{{\rm{int}}}^{\alpha }\) acting on species α defined via Eq. (8) and the total external force density given by \({{\bf{F}}}_{{\rm{ext}}}=\sum _{\alpha }{\rho }_{\alpha }{{\bf{f}}}_{{\rm{ext}}}^{\alpha }\).

We next divide Eq. (15) by the total density profile ρ(r, t) and use the definition of the total velocity profile, Eq. (13), in order to obtain

where we have defined the total internal and external force fields, fint(r, t) and fext(r, t), respectively, as

As we demonstrate below, fint(r, t) is one crucial one-body field that enables us to rationalize the nonequilibrium behavior of driven mixtures.

We restrict ourselves in the following to binary mixtures, such that the species are labeled by α = 1, 2. We view the total force field fint to act on both species in the same way, and also introduce a differential force density Gint(r, t) which drives the two species through and against each other. Hence using fint and Gint we express the underlying species-resolved internal force density fields \({{\bf{F}}}_{{\rm{int}}}^{\alpha }\) for α = 1, 2 as

We can invert this relationship and use Eq. (17) to obtain

Hence Eqs. (17) and (21) express a variable transformation from the species-resolved force densities \({{\bf{F}}}_{{\rm{int}}}^{(1)}({\bf{r}},t)\) and \({{\bf{F}}}_{{\rm{int}}}^{(2)}({\bf{r}},t)\) to the total force field fint(r, t) and the differential force density Gint(r, t). As we demonstrate below, each of the new one-body fields describes a unique physical effect. Briefly, fint contains effects that are also present in a one-component system, while Gint contains the genuine mixture contributions, such as drag and superdemixing.

The dynamics of the total density field are still governed by Eq. (16). To describe the mixture contributions, we introduce the density difference ρΔ and the current difference JΔ, respectively, via

where the continuity equation ∂ρΔ ∕ ∂t = −∇ ⋅ JΔ is readily obtained from subtraction of the species-resolved continuity equations, Eq. (6). We define the differential external force density as

The corresponding equation of motion is obtained by building the difference of the species-resolved one-body force density balance, Eq. (7), for α = 1 and 2, which yields

where, as before, fint(r, t) is given by Eq. (17) and Gint(r, t) is given by Eq. (21). The structure of Eq. (25) is crucial for the dynamics of driven mixtures. The differential current (left hand side) emerges from four different types of force density (right hand side): the first term is the ideal diffusive force density field due to gradients in the density difference. The second term generates a transport effect on ρΔ which is induced by the presence of fint. The third term is a genuine mixture contribution that acts directly on the density difference; recall the definition of Gint, Eq. (21). The fourth term is due to the external influence, cf. Eq. (24).

We next split the fields into adiabatic contributions (i.e., those that can be understood on the basis of a corresponding equilibrium system with the same partial density profiles) and superadiabatic contributions of genuine nonequilibrium character, according to

Due to linearity, the same variable transformation as before, Eqs. (17) and (21), relates the terms on the right hand side with the species-resolved force densities, Eq. (9). Hence for the adiabatic contributions:

where the total adiabatic force density is defined as \({{\bf{F}}}_{{\rm{ad}}}=\sum _{\alpha }{{\bf{F}}}_{{\rm{ad}}}^{\alpha }\). For the superadiabatic contributions:

where the total superadiabatic force density is defined as \({{\bf{F}}}_{\sup }=\sum _{\alpha }{{\bf{F}}}_{\sup }^{\alpha }\).

We summarize by inserting the adiabatic-superadiabatic splitting, Eqs. (26) and (27), into the velocity equation of motion, Eq. (16), and into the differential current, Eq. (25), which yields, respectively,

Equations (32) and (33) form the basis of our subsequent classification of the different types of occurring physical effects.

Ideal mixture

In order to highlight the fundamental nonequilibrium effects, we particularize to an “ideal” mixture, in which the internal interactions do not depend on the type of particle. Formally, this implies that the value of the internal interaction potential u(rN) is unchanged under permutation of the positions. For pair potentials (as we consider below) the inter-species pair potentials ϕαα(r) are identical to each other and are identical to the cross interaction potential \({\phi }_{\alpha \alpha ^{\prime} }(r)\) between particles of different species α and \(\alpha ^{\prime}\). Hence, \({\phi }_{\alpha \alpha ^{\prime} }(r)=\phi (r)\), where ϕ(r) is a universal function. Given that all the internal interactions are the same, the adiabatic force field only has a nontrivial component, \({{\bf{f}}}_{{\rm{ad}}}^{\alpha }={{\bf{f}}}_{{\rm{ad}}}\), where fad is universal (independent of species). No differential component occurs in the adiabatic system, hence Gad = 0, which simplifies the dynamics, cf. Eq. (33). Importantly, this symmetry does not apply to the external force field. Hence, in general \({{\bf{f}}}_{{\rm{ext}}}^{\alpha }({\bf{r}},t)\,\ne\,{{\bf{f}}}_{{\rm{ext}}}^{\alpha ^{\prime} }({\bf{r}},t)\) for \(\alpha\,\ne\,\alpha^{\prime}\), which imprints differences into the kinematic one-body fields ρα and Jα during the time evolution. Such driving is far from trivial. One might picture differently colored particles being driven through each other.

Next, we consider a special simplifying situation consisting of steady states characterized by a single direction of the flow along which all vector fields point, i.e., v, v1, v2, J, J1, J2 are all collinear. In the simulation results shown below this is the \(\hat{{\bf{y}}}\)-direction (the flow is in the “vertical” direction). All gradients in the system also share a common direction, which is orthogonal to the flow. In the simulations, this is the \(\hat{{\bf{x}}}\)-direction (the system is “horizontally” inhomogeneous). Such “perpendicular flow” geometry forms a class of common nonequilibrium situation encompassing e.g., simple shear flow, steady flow between parallel plates etc.

We split the superadiabatic forces into viscous (subscript “visc”), drag, and structural (subscript “struc”) contributions according to

where, as we show, fvisc is a viscous force field that arises from total shear motion, fstruc is a structural force field that sustains gradients of the total density distribution, Gdrag is a superadiabatic force density distribution that describes the friction effect that occurs due to counterflow (i.e., when vΔ ≠ 0), and Gstruc is the superadiabatic demixing force density. We demonstrate the validity of this interpretation below. On a formal level, the splitting in Eqs. (34) and (35) is uniquely defined by fvisc and Gdrag acting collinear with the flow, and fstruc and Gstruc acting perpendicular to it.

We can now separate the equations of motion according to the direction of the forces. In the flow direction, using Eqs. (34) and (35), we obtain from Eqs. (32) and (33), respectively,

which indicates that the total (scaled) flow (γv) arises from a competition of the external driving (fext) and the viscous forces (fvisc). The differential current (γJΔ) is counteracted by a transport effect that the viscous forces exert on the density difference (ρΔfvis), and the drag that any counterflow of the two species induces (2Gdrag), and it is driven by the external differential force density (\({{\bf{F}}}_{{\rm{ext}}}^{\Delta }\)).

In the gradient direction, we also use Eqs. (32) and (33), respectively, to obtain

Here, remarkably, the external forces do not appear explicitly. Equation (38) constitutes a force balance relationship, where the sum of the diffusive force, the adiabatic force, and the structural force cancel, such that no motion occurs. Equation (39) is crucial for understanding the physics of driven mixtures: The sum of the diffusive force density difference, −kBT ∇ ρΔ, and the effect of total adiabatic and structural force fields on the density difference, ρΔ(fad + fstruc), is balanced by the structural differential force density, 2Gstruc. This implies that Gstruc ≠ 0 can induce a density contrast ρΔ ≠ 0 in the system.

We can now revert to the species-labeled description and start from the general relationship

where the upper sign (+) applies to species 1, and the lower sign (−) applies to species 2. Application to the perpendicular geometry results in the following balance relations in the flow direction and in the gradient direction

where again ± corresponds to α = 1, 2. As we have four equations for the four unknown superadiabatic fields, we can solve for these, with the results:

where fext is the total external force field given by the linear combination, Eq. (18), and \({{\bf{F}}}_{{\rm{ext}}}^{\Delta }\) is the differential external force density defined via Eq. (24); both fields depend on the partial density profiles. As all quantities on the right hand side of Eqs. (43–46) are accessible in simulations, we have formulated a means to obtain a complete splitting of the nonequilibrium force contributions in the system.

The total species-resolved superadiabatic force field is then given by

where the first and the second term on the right hand side act in flow direction, and the third and the fourth term act in the gradient direction; again ± corresponds to α = 1, 2.

At the end of the results section we also analyze briefly a second case in “planar” geometry, in which there is only a single direction in the system (\(\hat{{\bf{y}}}\)) along which the flow occurs and also all gradients point. The system is transitionally invariant in \(\hat{{\bf{x}}}\). As the flow occurs in the direction of the gradients, in general, such situations will be nonstationary, i.e., time-dependent.

Power functional approximation

Power functional theory38 (PFT) is an exact variational approach to nonequilibrium dynamics in overdamped Brownian systems. PFT reduces to density functional theory in equilibrium. Within PFT, the superadiabatic force is obtained as a functional derivative with respect to the current,

Here \({P}_{t}^{{\rm{exc}}}\) is the superadiabatic excess power functional38, which is a functional of the density and current profiles of both species {ρα, Jα}. The superadiabatic force is therefore also a functional of both types of one-body fields: density profiles and current profiles.

Approximations for \({P}_{t}^{{\rm{exc}}}\) in monocomponent systems based on a series expansion of gradients of the velocity field have been proposed in refs. 42,43. The resulting superadiabatic forces describe viscous42 and structural effects43. In a binary mixture, besides the velocity gradients, the velocity difference between both species vΔ = v2 − v1 is a further key ingredient to construct approximated power functionals44.

The following approximation for \({P}_{t}^{{\rm{exc}}}\) reproduces semiquantitatively all types of superadiabatic forces in the system considered here:

where ρ2 indicates the square of the total density profile, as defined Eq. (11). The functional consists of four different terms, each one accounting for one type of superadiabatic force. The spatial dependence is local in density and semi-local (via the gradient) in velocity. The functional form in Eqs. (49–52) is based on expressions that contain low powers of the density and velocity profiles. The expressions in Eqs. (49) and (51) are of velocity gradient form42, with the former describing viscous42 and the latter describing structural effects43. Furthermore, the differential velocity vΔ, which captures the degree of interflow of the two components, appears quadratically in Eq. (50) as is appropriate to describe drag effects44. It couples in Eq. (51) to the divergence of the current, which creates a structural force. Finally, Eq. (52) generates the superdemixing force, as we will demonstrate below.

The prefactors of each term in Eqs. (49–52) are positive constants that represent the amplitude of the respective superadiabatic force contribution. We use these coefficients as fitting parameters (Numerical values are given below in the caption of the respective figure). In reality, these prefactors depend on microscopic features of the model, as the interparticle potential and are, in general, functionals of the density. The prime in Eq. (52) indicates the following time integral

with K(t) being a temporal convolution kernel with normalization ∫dtK(t) = 1 and the primes on the right hand side indicate dependence on \(t^{\prime}\). We do not investigate the specific form of K(t) in the present work further, as we are primarily concerned with steady states. The effective role that the kernel plays in steady state is that the functional derivative in Eq. (48) does not act on the primed terms.

The viscosity term. Equation (49), is the lowest order term in a power series expansion in the velocity gradient42 and accounts for the Stokes-like viscous force. A similar term containing the square of the divergence of the average velocity, instead of the square of the curl, does not produce any force in the current setup, since the velocity profile is free of divergence. The superadiabatic viscous force that results from differentiating Eq. (49) is species-independent and given by

where the leftmost derivatives act on each entire expression, and the second equation, Eq. (55), has been particularized for our current setup \({\bf{v}}({\bf{r}})={v}_{y}(x)\hat{{\bf{y}}}\) and constitutes a force in flow direction.

The second term, Eq. (50), describes the drag of particles of one species due to the flow of particles of the other species44. The resulting superadiabatic force is species-dependent. The corresponding force density is:

The structural superadiabatic force generated by the third term, Eq. (51), is species-independent,

As we will see, this force balances the sum of the adiabatic force and the diffusive force of the total density gradient.

The last term, Eq. (52), is also structural and the only one generating the superdemixing. The force density obtained via functional differentiation of Eq. (52) is

where only the functional derivative with respect to the unprimed velocity difference in Eq. (52) produces a force due to the structure of Eq. (53). Before presenting results, we first lay out the specifics of the microscopic model that we consider.

Brownian dynamics simulations

In the following we explicitly consider an equimolar two-dimensional binary mixture with a total of N = 1066 particles (\({{\mathcal{N}}}_{1}={{\mathcal{N}}}_{2}=532\)) interacting via the same quasi-hard core pair potential ϕ(r) = ϵσ/r36. Here, σ denotes the characteristic particle size, which sets our length scale, and ϵ sets the energy scale. The particles are subject to a homogeneous gravitational field in \(\hat{{\bf{y}}}\)-direction,

where g is the acceleration due to gravity, \(\hat{{\bf{y}}}\) is a unit vector along the vertical \(\hat{{\bf{y}}}\)-direction, and mα is the buoyant mass of species α. The only difference between the two species is that they have opposite buoyant masses, i.e., m1 = −m2. Although we make use of a gravitational field to illustrate the process of lane formation, other external fields such as magnetic and electric fields can also be used.

We simulate the system using Brownian dynamics simulations performed in a square simulation box of length L/σ = 35 with periodic boundary conditions in both directions. The total bulk density is hence ρbσ2 = Nσ2∕L2 = 0.87. The temperature is fixed to kBT/ϵ = 0.5. The particle trajectories are integrated in time via the Euler algorithm with a discrete time step Δt/τ = 3.0 × 10−5 in units of the reduced time τ = σ2γ/ϵ. The simulations of the laned state are initialized with the particles randomly located in a homogeneous state. Once the steady state is reached the system is sampled for a total time of ~106 τ.

Laned state

The magnitude of the external force that drives the two species against each other, mαg, highly influences the behavior of the system. Without gravity, particles of both species form an effectively homogeneous one-component system in equilibrium, in which the only difference between the species is an arbitrary label. At low values of gravity, the steady state remains homogeneously mixed, and the particles are driven slowly through each other, see the characteristic snapshot in Fig. 1a for a value of the external field m1g = 0.05 ϵ/σ. No forces act in the \(\hat{{\bf{x}}}\)-direction. The internal interactions lead to weak superadiabatic drag forces in the (flow) \(\hat{{\bf{y}}}\)-direction that partially counteract the external force.

For sufficiently high external driving, such as e.g., m1g = 1 ϵ/σ, the two species segregate into two lanes, see Fig. 1b. Each lane is characterized by the concentration of one species being significantly higher than that of the other (minority) species. In each lane there is a current of particles parallel to the external force corresponding to the dominant species. As shown above, there occur superadiabatic drag and viscous forces opposing the external forces, see Eqs. (36) and (37). In addition, in the (gradient) \(\hat{{\bf{x}}}\)-direction there is a balance of forces, cf. Eqs. (38) and (39). The sum of the ideal diffusion and the adiabatic force tries to mix the two species. These forces are, however, canceled by structural superadiabatic forces that keep the system in the demixed laned steady state. A brief animation of the particle flow in the homogeneous and in the laned stated is shown in Supplementary Movie 1.

The density profiles of the laned state are shown in Fig. 2a. There, the right lane (x > 0) is dominated by species 1 that possesses a positive buoyant mass, i.e., the external force is directed downwards. In the left lane (x < 0) the majority of particles belongs to species 2 with negative buoyant mass and therefore an upwards directed external force. Although here species 1 predominantly occupies the right lane, the state is degenerated in the sense that a swap of the two lanes can be compensated by a shift by L/2 in the \(\hat{{\bf{x}}}\)-direction (due to periodic boundary conditions). The total density profile, Fig. 2a, increases toward the centers of the lanes and decreases at the interfaces, although it is quite homogeneous as compared to the single species density profiles.

Kinematic fields: (a) total density profile ρ (black dotted line) and partial density profiles ρ1 (orange solid line) and ρ2 (blue dashed line), (b) flow component of the total velocity profile vy (black dotted line), see Eq. (13), and of the partial velocity profiles \({v}_{1}^{y}\) (orange solid line) and \({v}_{2}^{y}\) (blue dashed line). Species-resolved forces (c) and force densities (d) acting in flow direction, Eq. (10): external \({{\bf{f}}}_{{\rm{ext}}}^{\alpha }\) (dashed lines), and superadiabatic \({{\bf{f}}}_{\sup }^{\alpha }\) (solid lines), which is the sum of viscous and drag, cf. Eq. (47). Species-resolved forces (e) and force densities (f) acting in gradient direction: sum of adiabatic and diffusive forces (dotted lines) and superadiabatic (solid lines), cf. Eq. (42). In all plots the line color indicates the species: orange (blue) for species 1 (2). The arrows indicate the direction of the force or force density. Black circles indicate points where the force or force density vanishes. All plots are for driving m1g = 1.0ϵ∕σ and all values are presented as functions of the x-coordinate.

In Fig. 2b we show the velocity profiles. Only the flow component of the velocity profiles \({v}_{\alpha }^{y}\) does not vanish in steady state. The total velocity profile clearly shows the motion of particles in opposite directions in the two lanes, irrespective of the species. The total velocity is directed downwards in the right lane and upwards in the left lane, while being zero at the interfaces, as is consistent with the symmetry of the system.

Forces acting in flow direction

We focus first on the species resolved force balance equation, Eq. (10). The flow components of the forces and of the force densities are presented in Fig. 2c, d, respectively. In what follows we focus the discussion on species 1. Due to the symmetry of the system the behavior of species 2 follows directly. Only two types of forces act in flow direction, the constant external force field \({{\bf{f}}}_{{\rm{ext}}}^{\alpha }\), Eq. (59), and the superadiabatic force field due to interparticle interactions \({{\bf{f}}}_{\sup }^{\alpha }\). Adiabatic (\({{\bf{f}}}_{{\rm{ad}}}^{\alpha }\)) and diffusive (\(-{k}_{{\rm{B}}}T\nabla \mathrm{ln}{\rho }_{\alpha }\)) forces appear only when gradients of the density profile are present. As the system is homogeneous in the flow direction, such contributions do not occur in this direction. Therefore, the internal forces in flow direction are purely superadiabatic.

For those particles located in the lane for which its species is in the majority (e.g., species 1 in the right lane in Fig. 2b), the velocity and the external force are parallel, while the internal force opposes both. For those particles in the lane for which its species is in the minority (e.g., species 2 in the right lane in Fig. 2b) the velocity and the external force are antiparallel. This is caused by a strong internal force, mostly created by particles of the opposite species which dominates the lane, that drags the particles of the minority species. The force densities in flow direction are shown in Fig. 2d. Force and force densities in gradient direction are depicted in Fig. 2e, f, respectively. The force densities are the actual contributions to the current of particles (up to a multiplicative constant given by the inverse friction coefficient) and are therefore a macroscopically accessible quantity.

Next, we split the species-resolved superadiabatic forces, Eq. (47), in flow direction in its species-dependent and species-independent contributions, Eq. (41), which are the viscous force fvisc, Eq. (43), and the drag ±Gdrag, Eq. (44), respectively. Both are of the superadiabatic kind.

The forces are shown in Fig. 3a, b, and the force densities in Fig. 3c. The species-dependent term ±Gdrag is the dominant part and describes the drag of one species due to motion of the other species. For example, for species 1 this force density is high in the lane of particles of species 2 (left lane) and points upwards. The species-independent force fvisc points in the direction opposite to the total velocity v, as corresponds to a viscous effect. The amplitude of the viscous force is relatively small as compared to that of the drag force. However, the maxima (absolute value) of fvisc occur at the peaks of the partial densities. As a result, the viscous force density ραfvisc introduces a relevant correction to the dominant species-dependent force density, see Fig. 3c.

a Species-independent superadiabatic force fvisc (dark solid green), species-dependent superadiabatic force acting on species 1 (solid orange), Gdrag∕ρ1, and 2 (solid blue), −Gdrag∕ρ2. b Enlarged view of the viscous force. c Species-dependent force density Gdrag acting on species 1 (solid orange), and species-independent force density acting on species 1 (orange-dark green), fviscρ1. The arrows (colored according to the corresponding data set) indicate the direction of the force. The symbols show the theoretical predictions for the viscous force (a), (b) force and the drag force density (c). We have set Cvisc = 2ϵτσ2 and Cdrag = 8.5ϵτ in Eqs. (55) and (56), respectively.

A comparison between the Stokes-like viscous force predicted by our power functional approximation, Eq. (55), and the viscous force measured in simulations is shown in Fig. 3b. The predicted force has the correct sign everywhere (opposite of the total flow). However, due to the spatially local approximation taken in Eq. (55) and the strong driving conditions, the agreement is not perfect. The drag force predicted by PFT, Eq. (56), also shows a good agreement with the simulation data, see Fig. 3c.

Forces acting in gradient direction

In the gradient direction \(\hat{{\bf{x}}}\), which is perpendicular to the flow, no external force is applied and the system is in steady state with no flow along this direction, cf. Eq. (42). The density modulation (formation of lanes), Fig. 2a, is solely created by the flow along \(\hat{{\bf{y}}}\), Fig. 2b.

The species-resolved net force balance, Eq. (10), vanishes in the \(\hat{{\bf{x}}}\)-direction, and both adiabatic \({{\bf{f}}}_{{\rm{ad}}}^{\alpha }\) and superadiabatic \({{\bf{f}}}_{\sup }^{\alpha }\) forces contribute to the internal force. For species 1 the sum of adiabatic and diffusive, \(-{k}_{{\rm{B}}}T\nabla \mathrm{ln}{\rho }_{\alpha }\), forces attempts to move particles in the center of the simulation box to the left and particles at the borders of the box to the right, see Fig. 2e, f. Hence, as could be expected, the sum of the diffusive and the adiabatic forces pushes particles outside of the majority lane and therefore tries to mix the two species by eliminating density gradients. The superadiabatic force in gradient direction balances the diffusion and the adiabatic forces by pushing particles into their majority lane and out of their minority lane, Fig. 2e, f. The superadiabatic force is therefore the only force that creates and sustains the demixing and segregation into lanes in steady state. Superadiabatic forces are therefore crucial for the description of lane formation, as expected given the nonequilibrium nature of the phenomenon.

The adiabatic forces are obtained by sampling the internal forces in the adiabatic equilibrium system. The adiabatic equilibrium system is also a symmetric mixture with the same quasi-hard interparticle interactions regardless of the species. The only difference between the real nonequilibrium and the adiabatic equilibrium systems is that the external nonconservative driving force is switched off in the adiabatic equilibrium system and replaced by conservative external forces generated by two potentials \({V}_{{\rm{ad}}}^{\alpha }\) that reproduce the same density profiles as in nonequilibrium. The adiabatic potentials are obtained following the procedure described in “Methods” section, where also results are shown for the adiabatic potentials and the density profiles in the adiabatic system.

In the adiabatic system, the external potential counteracts both the ideal diffusive force \(-{k}_{{\rm{B}}}T\nabla \mathrm{ln}{\rho }_{\alpha }\) and the adiabatic (internal) force \({{\bf{f}}}_{{\rm{ad}}}^{\alpha }\). The diffusive force and the adiabatic force have two very distinct effects, which are schematically illustrated in Fig. 4a. Quantitative plots of both force and force density profiles for species 1 are shown in Fig. 4b, c, respectively. Force and force density profiles for species 2 are depicted in Fig. 4d, e. The diffusive force is the only force that attempts to mix both species. In contrast, the adiabatic force field is the same for all particles, independently of the species, due to the symmetry of the internal interactions. That is \({{\bf{f}}}_{{\rm{ad}}}^{\alpha }={{\bf{f}}}_{{\rm{ad}}}\), as discussed before. The adiabatic force tries to eliminate the density gradients of the total density profile ρ = ρ1 + ρ2 by pushing particles of both species toward the interfaces between the two lanes.

a Partial snapshots of the laned state at gravity m1g = 1.0ϵ∕σ. The arrows indicate the direction of the forces acting on species 1 and 2. The diffusive force field \(-{k}_{{\rm{B}}}T\nabla \mathrm{ln}{\rho }_{\alpha }\) (violet arrows) tries to mix both species. The adiabatic force field (green) is the same for both species. Force (b) and force density (c) profiles acting on species 1 in \(\hat{{\bf{x}}}\)-direction as a function of x: total force: adiabatic plus diffusion (orange dotted), diffusive force (violet dashed), and adiabatic force (green solid). Panels d and e are the same as panels b and c, respectively, but for species 2: total force (blue dotted), diffusion (violet dashed), and adiabatic (green solid).

We next split the species-resolved superadiabatic forces, Eq. (47), into the species-independent fstruc, Eq. (45), and the species-dependent ±Gstruc, Eq. (46), contributions in gradient direction. Both contributions are of the structural type in the sense that they sustain the density gradients and are non-dissipative. Fig. 5a illustrates schematically the different effects of fstruc and Gstruc. The actual profiles are displayed in Fig. 5b, c.

a Partial snapshots of the laned state (m1g = 1.0ϵ∕σ). The arrows indicate the direction of the species-independent fstruc and dependent ± Gstruc superadiabatic forces in gradient direction. The brightness of the particles in the upper snapshot indicates the total density modulation (brighter regions are less dense). Species-independent superadiabatic force fstruc (b) and species-dependent force density Gstruc acting on species 1 (c). Lines are simulation data and symbols denote the power functional approximation given in Eqs. (45) and (58) with parameters Cstruc = 10.5ϵτ2σ2, and Dstruc = 0.73ϵτ2. d Negative of the species-independent superadiabatic force−fstruc (dark green dashed) and the adiabatic excess force fad (bright green solid). e Negative of the thermal diffusion force associated to the total density (blue) and sum of the species-independent superadiabatic force and the adiabatic force (black dotted).

The species-independent superadiabatic force in gradient direction, fstruc, pushes particles from the interfaces toward the centers of the lanes, creating the total densty modulation, see Fig. 5b. fstruc is almost the opposite of the adiabatic force fad, as shown in Fig. 5d where we plot the adiabatic force, and −fstruc. These two terms, however, do not exactly cancel each other as the sum of fstruc and the adiabatic force shows a clear signal (see Fig. 5e) that cancels exactly the diffusive force orginated by the gradient of the total density profile, cf. Eq. (45). This diffusive term also describes a species-independent effect.

The species-dependent force density +Gstruc transports particles of species 1 away from the left lane into the right lane, see Fig. 5c. The term −Gstruc acts on particles of species 2 in the opposite way. This superadiabatic contribution is precisely the opposite of the contribution due to the local demixing, compare Fig. 5c and the diffusive force density shown in Fig. 4c. Therefore, the species-dependent term Gstruc sustains the demixing of the two species in two lanes in steady state.

The sum of both superadiabatic structural terms in gradient direction cancels the diffusive and the adiabatic contributions, cf. Eq. (42). Our power functional approximation, Eqs. (57) and (58), is in very good agreement with the simulation data for both fstruc and Gstruc as shown in Fig. 5b, c, respectively.

Jammed state

We conclude the results section with a brief discussion of the jammed state, see Fig. 6a. The jammed state can be found at intermediate values of gravity, and in it flow and gradient directions coincide. This state occurs if the two species block each other during the diffusive process induced by the external field. The state is homogeneous in \(\hat{{\bf{x}}}\)-direction, and it is characterized by a significant change of the total density in \(\hat{{\bf{y}}}\)-direction. The opposite external driving of the two species leads to the formation of a compressed region with similar concentrations of both species, high total density, and incipient crystalline order. This region is surrounded by two regions rich in particles of only one species that press against the compressed area. In the jammed state, strong superadiabatic forces act against the external fields. In addition, the adiabatic and diffusive forces try to smooth the total density profile. In contrast to the laned state, the demixing in the jammed state occurs along the direction of the external driving force. In our simulations the jammed state is metastable, but it persists for very long times, which allows for systematic study of the forces.

a Characteristic snapshot. The orange (blue) arrows indicate the forces acting on species 1 (2). b Total density profile ρ (black dotted line), and partial density profiles ρ1 (solid orange) and ρ2 (blue dashed). c Total velocity profile vy (black dotted), and partial velocity profiles \({v}_{1}^{y}\) (orange solid) and \({v}_{2}^{y}\) (blue dashed). d Current profiles: total current profile jy (black dotted), and partial current profiles \({j}_{1}^{y}\) (orange solid) and \({j}_{2}^{y}\) (blue dashed). e Forces acting in \(\hat{{\bf{y}}}\)-direction: external (dashed), diffusive plus adiabatic (dotted), and superadiabatic (solid). The color indicates the species: orange (blue) for species 1 (2). f Adiabatic and diffusive forces acting in \(\hat{{\bf{y}}}\)-direction acting on species 1: Sum of both forces (orange dotted), adiabatic (green solid), and ideal diffusion (purple dashed). Data obtained for a value of gravity m1g = 0.7ϵ∕σ. All quantities are presented as a function of the y-coordinate.

To characterize the jammed state we set the gravity to m1g = 0.7ϵ ∕ σ and split the time evolution of the system in time windows of 20τ. Only those time windows in which the difference between the maximum and the minimum of the total density is higher than 0.2σ2 are considered to be in the jammed state. We have found by visual inspection of microstates that this is a sufficiently accurate criterion for identifying states that one would classify as being transiently jammed. For flowing states and for less well-characterized states, the density distribution is typically more homogeneous, such that the chosen criterion removes these states from the sampling. Using several simulations, we average over these relevant windows for a total sampling time of 105 τ. The density profiles, Fig. 6b, show the demixing along the \(\hat{{\bf{y}}}\)-axis. The particles of species 1 (2) accumulate at the top (bottom) of the simulation box. In the center of the box there is a region with similar concentrations of both species. The total density shows a small modulation with a global maximum located in the middle of the box (in each time window we translate the data such that the maximum density occurs in the the middle of the box). The velocity profiles are shown in Fig. 6c. Only the \(\hat{{\bf{y}}}\)-component of the velocity is non-zero. The total velocity is almost negligible across the entire systemf. The velocity of species 1 almost vanishes everywhere except at the bottom of the simulation box, i.e., in the region rich in particles of species 2. Here, the velocity of species 1 is negative. Hence, particles of species 1 move toward the top of the simulation box (recall that we use periodic boundary conditions) where the species 1 dominates. Exactly the opposite behavior is observed in species 2, as expected due to symmetry considerations.

The total current vanishes, see Fig. 6d, and the partial currents are small and indicate that the system is still undergoing compression. Given that the partial currents are not constant, it is clear the system is not in steady state. Nevertheless, the currents are very small and rather homogeneous, which justifies the assumption of a quasi-steady state. For other systems the jammed state has been observed to be steady. This is the case of a 2D hard disk system with very low opposite driving at zero temperature45, and also on a square lattice model21.

The species-resolved forces in \(\hat{{\bf{y}}}\)-direction split into diffusion, adiabatic, superadiabatic, and external, cf. Eq. (10). Plots of each contribution are shown in Fig. 6e. We compute the adiabatic force via the adiabatic potential, as described in “Methods” section.

The (constant) external force for both species point in opposite directions. The sum of the thermal diffusion and the adiabatic force is for both species positive at the top and mostly negative at the bottom of the simulation box. Hence, this force field tries to smooth the density modulations by transporting particles away from the center toward the low density regions. The superadiabatic force for species 1 is everywhere directed upwards against the external force and has a maximum at the bottom of the sample, the region dominated by species 2.

The thermal diffusion and the adiabatic force acting on species 1 are shown in Fig. 6f. The adiabatic force is positive at the top of the box and negative at the bottom, moving particles away from the center in order to smooth the total density profile. Similarly, the ideal diffusion force tries to smooth the partial density profile of species 1.

Recall that in the laned state, the diffusive force is the only force counteracting the demixing, while the adiabatic force has a phenomenologically irrelevant effect. In the jammed state, however, the adiabatic force has a prominent effect, while the diffusion term is only a small contribution to the forces present in the adiabatic state. The flow in the jammed state is curl-free instead of divergence-free (which is the case in in the laned state). Hence, the leading terms in the expansion of the excess free power for the viscous and the species-independent structural forces will differ from those in Eqs. (49) and (52), respectively.

Discussion

By splitting the nonequilibrium superadiabatic forces of a binary colloidal mixture into species-dependent and independent contributions, we have identified a structural force contribution that induces demixing of two different species in nonequilibrium. This superadiabatic force is responsible for the formation of lanes in oppositely driven binary colloidal systems. The force counteracts the ideal thermal diffusive force that arises as a consequence of the mixing entropy generated by a gradient in composition between the two lanes.

The entropy-driven demixing that occurs in equilibrium mixtures of hard bodies, see e.g., ref. 46, is a well-known phenomenon. There, the interparticle interactions generates an internal adiabatic force that counteracts the ideal entropy of mixing (diffusive force) and hence sustains the density gradients. The mechanism behind the demixing in lane formation is completely different. Here, the adiabatic force only leads to a minor modulation of the total density and does not attempt to demix the species. Although we have analyzed ideal symmetric mixtures, we expect this to be true also in asymmetric mixtures that could be considered in future studies.

Lane formation is a purely superadiabatic effect. Consequently a direct theoretical description of laning via dynamical density functional theory47,48,49, in which only adiabatic forces are considered, is not possible and phenomenological ad-hoc corrections must be included14. For the related, but different case of colloidal suspensions in confinement, Aerov and Krüger argued50 that dynamical density functional is insufficient to describe the effects of shear.

We have presented here a different approach based on power functional theory38, an exact variational approach for nonequilibrium situations. Power functional theory incorporates superadiabatic effects via a functional of both density and velocity profiles. Our power functional approximation reproduces semiquantitatively all superadiabatic forces present in the system, and, to the best of our knowledge, it constitutes the first theoretical approach that describes lane formation from first principles.

Although we have focused our study on lane formation, our approach to analyze the force contributions and our power functional approximation are general and applicable to other out-of-equilibrium situations in multicomponent colloidal systems. In particular, our work paves the way to study superadiabatic forces inside channels where ratchet-like wall shapes can determine the direction of the motion within the lanes51, and the description using power functional theory of the complete dynamics of sedimentation of binary mixtures from an initial uniform state to the formation of the sedimentation-diffusion-equilibrium stacking sequence52,53. The power functional approach presented here can also help to understand the differences and similarities between lane formation in oppositely driven mixtures and in one-component sheared systems54,55. There, the formation of lanes in steady state is induced by a shear field and likely sustained by a superadiabatic force. It would be interesting to relate the laning effect to the physics of active Brownian particles. The power functional approach is well equipped for systematic investigation of the underlying coupled nature of the nonequilibrium many-body systems, as the different types of driving (whether active44,56,57,58 or external as in the present case) enter explicitly; the superadiabatic free power functional, however, is a universal object, independent of the specific form of driving.

Methods

Adiabatic construction

The internal force field is a functional of the density and the velocity profiles and can be split into adiabatic and superadiabatic contributions. Mathematically, the adiabatic force is the term that depends only on the density profile. Physically, the adiabatic force represents the internal force of an equilibrium system that shares the same density profile(s) as the actual out-of-equilibrium system. In ref. 41 Fortini et al. presented the first simulation method for sampling the superadiabatic forces in a monocomponent BD nonequilibrium system. The method relies on numerically finding the adiabatic external potential that generates the desired density profile in equilibrium. A related and improved iterative (custom flow) method to numerically find the adiabatic potential is presented in ref. 40. We follow here another approach to find the adiabatic potential, based on classical density functional theory (DFT)47. In DFT the adiabatic force is a functional of the one-body density profiles, and given by the functional derivative

where \({F}_{{\rm{exc}}}[\{{\rho }_{\alpha ^{\prime} }\}]\) is the excess (over ideal) Helmholtz free energy functional.

The adiabatic system is obtained by finding the species-dependent adiabatic external potentials \({V}_{{\rm{ad}}}^{\alpha }(x,t)\), which are constructed such that the equilibrium one-body densities for both species in the adiabatic (equilibrium) system equal those in the nonequilibrium system. For the laned system, the system is homogeneous in the flow \(\hat{{\bf{y}}}\)-direction and therefore the adiabatic potentials can only depend on the x—coordinate. In the adiabatic (equilibrium) system, the force balance reads

In order to sample the adiabatic reference system of the laned state, we use Monte Carlo simulations with the same values of \({{\mathcal{N}}}_{\alpha }\), L, and kBT as the nonequilibrium BD system. We initialize the adiabatic system with a configuration taken from the BD simulations and then equilibrate the system. The maximum displacement each particle is allowed to move in one Monte Carlo step is set such that 25–30% of the moves are accepted. We then sample data for ~1011 Monte Carlo sweeps (MCS). A MCS is defined as an attempt to individually move all particles in the system.

In refs. 40,41 iterative methods for finding the adiabatic potential that enters in Eq. (61) are presented. An initial guess for the potential is iteratively adjusted until the density profile equals the corresponding counterpart in the nonequilibrium system. Here, we have to match two density profiles, one for each species. As the modulation of the total density is small, a calculation of the adiabatic potentials using a simple density functional based on the equation of state of scaled-particle theory (SPT) for hard-disks yields excellent results. Within SPT the compressibility factor of an homogeneous system of hard disks is Z = (1 − η)−2 59, with η = ρbπσ2∕4 the total packing fraction of the system. Here, ρb is the bulk number density. An expression for the excess free energy per particle ψexc follows from Z via integration60:

Using the above expression we construct an approximation for the excess free energy functional:

in which the excess free energy is evaluated in a weighted density given by

Since the mixture is symmetric only the total density ρ = ρ1 + ρ2 enters the expression for the excess free energy. The resulting adiabatic force fad via functional differentiation is species-independent and directed along the gradient direction

Equations (61) and (65) yield an expression for the species-dependent adiabatic potential

where Λα is the (irrelevant) thermal wavelength of species α and the spatial argument of \(\bar{\rho }\) and η was omitted for clarity.

Figure 7a displays results for the adiabatic potentials. As expected, the potential for each species is high in the region of the respective minority lane and low in the majority lane, with a total difference between maximum and minimum of approximately 1.3ϵ (equal to 2.6kBT). The external forces created by the two adiabatic potentials segregate the two species in the equilibrium system. In Fig. 7b, we present the total density sampled in the adiabatic system and that in the nonequilibrium system. Both systems have almost the same density profiles, which shows the quality of the adiabatic construction. The species-dependent density profiles in the adiabatic system are also in very good agreement with those in out-of-equilibrium (not shown).

a Adiabatic external potentials \({V}_{{\rm{ad}}}^{\alpha }\) in the adiabatic (equilibrium) system for species 1 (orange solid) and species 2 (blue dashed) as a function of x. b Total density profile ρ sampled via Brownian Dynamics in nonequilibrium steady state (black dotted) and via Monte Carlo in the corresponding adiabatic equilibrium system (violet solid).

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

References

Vlasov, A. Y. & Masters, A. J. Binary mixtures of hard spheres: how far can one go with the virial equation of state? Fluid Phase Equi. 212, 183 (2003).

Ramakrishnan, S., Fuchs, M., Schweizer, K. S. & Zukoski, C. F. Entropy driven phase transitions in colloid-polymer suspensions: tests of depletion theories. J. Chem. Phys. 116, 2201 (2002).

Paricaud, P., Galindo, A. & Jackson, G. Understanding liquid-liquid immiscibility and LCST behaviour in polymer solutions with a Wertheim TPT1 description. Mol. Phys. 101, 2575 (2003).

Paricaud, P., Varga, S. & Jackson, G. Study of the demixing transition in model athermal mixtures of colloids and flexible self-excluding polymers using the thermodynamic perturbation theory of Wertheim. J. Chem. Phys. 118, 8525 (2003).

Vroege, G. J. & Lekkerkerker, H. N. W. Theory of the isotropic nematic nematic phase-separation for a solution of bidisperse rodlike particles. J. Phys. Chem. 97, 3601 (1993).

Varga, S., Galindo, A. & Jackson, G. Phase behavior of symmetric rod-plate mixtures revisited: biaxiality versus demixing. J. Chem. Phys. 117, 10412 (2002).

Seiferling, F., de las Heras, D. & Telo da Gama, M. Percolation in binary and ternary mixtures of patchy colloids. J. Chem. Phys. 145, 074903 (2016).

Roth, R., Rauscher, M. & Archer, A. J. Selectivity in binary fluid mixtures: static and dynamical properties. Phys. Rev. E 80, 021409 (2009).

Rica, R. A. et al. Capacitive mixing for harvesting the free energy of solutions at different concentrations. Entropy 15, 1388 (2013).

Boon, N. & van Roij, R. Blue energy’ from ion adsorption and electrode charging in sea and river water. Mol. Phys. 109, 1229 (2011).

Thiele, U., Archer, A. J. & Pismen, L. M. Gradient dynamics models for liquid films with soluble surfactant. Phys. Rev. Fluids 1, 083903 (2016).

Guo, S. & Liu, C. T. Phase stability in high entropy alloys: formation of solid-solution phase or amorphous phase. Prog. Nat. Sci. 21, 433 (2011).

Dzubiella, J., Hoffmann, G. P. & Löwen, H. Lane formation in colloidal mixtures driven by an external field. Phys. Rev. E 65, 021402 (2002).

Chakrabarti, J., Dzubiella, J. & Löwen, H. Dynamical instability in driven colloids. Europhys. Lett. 61, 415 (2003).

Chakrabarti, J., Dzubiella, J. & Löwen, H. Reentrance effect in the lane formation of driven colloids. Phys. Rev. E 70, 012401 (2004).

Leunissen, M. E. et al. Ionic colloidal crystals of oppositely charged particles. Nature 437, 235 (2005).

Rex, M. & Löwen, H. Lane formation in oppositely charged colloids driven by an electric field: chaining and two-dimensional crystallization. Phys. Rev. E 75, 051402 (2007).

Vissers, T. et al. Lane formation in driven mixtures of oppositely charged colloids. Soft Matter 7, 2352 (2011).

Sütterlin, K. R. et al. Dynamics of lane formation in driven binary complex plasmas. Phys. Rev. Lett. 102, 085003 (2009).

Du, C.-R., Sütterlin, K. R., Ivlev, A. V., Thomas, H. M. & Morfill, G. E. Model experiment for studying lane formation in binary complex plasmas. EPL 99, 45001 (2012).

Ohta, H. Lane formation in a lattice model for oppositely driven binary particles. EPL 99, 40006 (2012).

Menzel, A. M. Unidirectional laning and migrating cluster crystals in confined self-propelled particle systems. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 25, 505103 (2013).

Couzin, I. D. & Franks, N. R. Self-organized lane formation and optimized traffic flow in army ants. Proc. R. Soc. London B 270, 139 (2003).

Cividini, J., Hilhorst, H. & Appert-Rolland, C. Crossing pedestrian traffic flows, the diagonal stripe pattern, and the chevron effect. J. Phys. A Math. Gen. 46, H5002 (2013).

Dzubiella, J. & Löwen, H. Pattern formation in driven colloidal mixtures: tilted driving forces and re-entrant crystal freezing. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 14, 9383 (2002).

Gerloff, S., Vezirov, T. A. & Klapp, S. H. L. Shear-induced laning transition in a confined colloidal film. Phys. Rev. E 95, 062605 (2017).

Wysocki, A. & Löwen, H. Oscillatory driven colloidal binary mixtures: axial segregation versus laning. Phys. Rev. E 79, 041408 (2009).

Götze, I. O. & Gompper, G. Flow generation by rotating colloids in planar microchannels. EPL 92, 64003 (2010).

Grünwald, M., Tricard, S., Whitesides, G. M. & Geissler, P. L. Exploiting non-equilibrium phase separation for self-assembly. Soft Matter 12, 1517 (2016).

Rex, M. & Löwen, H. Influence of hydrodynamic interactions on lane formation in oppositely charged driven colloids. Eur. Phys. J. E 26, 143 (2008).

Delhommelle, J. Should “lane formation” occur systematically in driven liquids and colloids?. Phys. Rev. E 71, 016705 (2005).

Glanz, T. & Löwen, H. The nature of the laning transition in two dimensions. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 24, 464114 (2012).

Wächtler, C. W., Kogler, F. & Klapp, S. H. L. Lane formation in a driven attractive fluid. Phys. Rev. E 94, 052603 (2016).

Kogler, F. & Klapp, S. H. L. Lane formation in a system of dipolar microswimmers. EPL 110, 10004 (2015).

Klymko, K., Geissler, P. L. & Whitelam, S. Microscopic origin and macroscopic implications of lane formation in mixtures of oppositely driven particles. Phys. Rev. E 94, 022608 (2016).

Poncet, A., Bénichou, O., Démery, V. & Oshanin, G. Universal long-ranged correlations in driven binary mixtures. Phys. Rev. Lett. 118, 118002 (2017).

Kohl, M., Ivlev, A. V., Brandt, P., Morfill, G. E. & Löwen, H. Microscopic theory for anisotropic pair correlations in driven binary mixtures. J. Phys. 24, 464115 (2012).

Schmidt, M. & Brader, J. M. Power functional theory for Brownian dynamics. J. Chem. Phys. 138, 214101 (2013).

Brader, J. M. & Schmidt, M. Power functional theory for the dynamic test particle limit. J. Phys. 27, 194106 (2015).

de las Heras, D., Renner, J. & Schmidt, M. Custom flow in overdamped Brownian dynamics. Phys. Rev. E 99, 023306 (2019).

Fortini, A., de las Heras, D., Brader, J. M. & Schmidt, M. Superadiabatic forces in Brownian many-body dynamics. Phys. Rev. Lett. 113, 167801 (2014).

de las Heras, D. & Schmidt, M. Velocity gradient power functional for Brownian dynamics. Phys. Rev. Lett. 120, 028001 (2018).

Stuhlmüller, N. C. X., Eckert, T., de las Heras, D. & Schmidt, M. Structural nonequilibrium forces in driven colloidal systems. Phys. Rev. Lett. 121, 098002 (2018).

Krinninger, P., Schmidt, M. & Brader, J. M. Nonequilibrium phase behaviour from minimization of free power dissipation. Phys. Rev. Lett. 117, 208003 (2016).

Reichhardt, C. & Olson Reichhardt, C. J. Velocity force curves, laning, and jamming for oppositely driven disk systems. Soft Matter 14, 490 (2018).

Adams, M., Dogic, Z., Keller, S. L. & Fraden, S. Entropically driven microphase transitions in mixtures of colloidal rods and spheres. Nature 393, 349 (1998).

Evans, R. The nature of the liquid-vapour interface and other topics in the statistical mechanics of non-uniform, classical fluids. Adv. Phys. 28, 143 (1979).

Marconi, U. M. B. & Tarazona, P. Dynamic density functional theory of fluids. J. Chem. Phys. 110, 8032 (1999).

Archer, A. J. & Evans, R. Dynamical density functional theory and its application to spinodal decomposition. J. Chem. Phys. 121, 4246 (2004).

Aerov, A. A. & Krüger, M. Driven colloidal suspensions in confinement and density functional theory: Microstructure and wall-slip. J. Chem. Phys. 140, 094701 (2014).

Oliveira, C. L., Vieira, A. P., Helbing, D., Andrade, J. S. & Herrmann, H. J. Keep-left behavior induced by asymmetrically profiled walls. Phys. Rev. X 6, 011003 (2016).

de las Heras, D. et al. Floating nematic phase in colloidal platelet-sphere mixtures. Sci. Rep. 2, 789 (2012).

de las Heras, D. & Schmidt, M. Phase stacking diagram of colloidal mixtures under gravity. Soft Matter 9, 8636 (2013).

Scacchi, A., Archer, A. J. & Brader, J. M. Dynamical density functional theory analysis of the laning instability in sheared soft matter. Phys. Rev. E 96, 062616 (2017).

Stopper, D. & Roth, R. Nonequilibrium phase transitions of sheared colloidal microphases: results from dynamical density functional theory. Phys. Rev. E 97, 062602 (2018).

Krinninger, P. & Schmidt, M. Power functional theory for active Brownian particles: general formulation and power sum rules. J. Chem. Phys. 150, 074112 (2019).

Hermann, S., Krinninger, P., de las Heras, D. & Schmidt, M. Phase coexistence of active Brownian particles. Phys. Rev. E 100, 052604 (2019).

Hermann, S., de las Heras, D. & Schmidt, M. Non-negative interfacial tension in phase-separated active Brownian particles. Phys. Rev. Lett. 123, 268002 (2019).

Helfand, E., Frisch, H. L. & Lebowitz, J. L. Theory of the two- and one-dimensional rigid sphere fluids. J. Chem. Phys. 34, 1037 (1961).

Hansen, J.-P. & McDonald, I. R. Theory of Simple Liquids, 4th edn. (Academic Press, London, 2013).

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by the German Research Foundation (DFG) via SCHM 2632/1-1.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T.G. performed the Brownian dynamics simulations and the analysis of the data. D.d.l.H. and M.S. designed and conceived the work and developed the theory. All authors contributed to the preparation of the paper.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Geigenfeind, T., de las Heras, D. & Schmidt, M. Superadiabatic demixing in nonequilibrium colloids. Commun Phys 3, 23 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-020-0287-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-020-0287-5

This article is cited by

-

Shear-induced deconfinement of hard disks

Colloid and Polymer Science (2020)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.