Abstract

Sulfur belongs among H2O, CO2, and Cl as one of the key volatiles in Earth’s chemical cycles. High oxygen fugacity, sulfur concentration, and δ34S values in volcanic arc rocks have been attributed to significant sulfate addition by slab fluids. However, sulfur speciation, flux, and isotope composition in slab-dehydrated fluids remain unclear. Here, we use high-pressure rocks and enclosed veins to provide direct constraints on subduction zone sulfur recycling for a typical oceanic lithosphere. Textural and thermodynamic evidence indicates the predominance of reduced sulfur species in slab fluids; those derived from metasediments, altered oceanic crust, and serpentinite have δ34S values of approximately −8‰, −1‰, and +8‰, respectively. Mass-balance calculations demonstrate that 6.4% (up to 20% maximum) of total subducted sulfur is released between 30–230 km depth, and the predominant sulfur loss takes place at 70–100 km with a net δ34S composition of −2.5 ± 3‰. We conclude that modest slab-to-wedge sulfur transport occurs, but that slab-derived fluids provide negligible sulfate to oxidize the sub-arc mantle and cannot deliver 34S-enriched sulfur to produce the positive δ34S signature in arc settings. Most sulfur has negative δ34S and is subducted into the deep mantle, which could cause a long-term increase in the δ34S of Earth surface reservoirs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Sulfur is one of the most common volatiles on Earth. It plays key roles in, for example, the redox evolution of the sub-arc mantle1,2, the formation of ore deposits2, and the composition of the atmosphere through volcanic SO2 degassing3. Subduction zones are the primary locations for the global sulfur cycle, transporting sulfur to the deep mantle via the descending slab or returning it to the surface by arc magmatism2,4,5. Compared to fresh MORB, the relatively high sulfur concentrations ([S], up to 3000 µg g−1) and positive δ34S values (+5 to +11‰) of volcanic rocks and melt inclusions in some arcs (e.g., Western Pacific)4,5,6,7, and the presence of sulfate in mantle xenoliths8, have been attributed to the addition of slab-derived sulfate to arc magmas by fluids8,9. Alternatively, some deep arc cumulates (e.g., Eastern Pacific) with mantle-like δ34S values suggest more limited slab-derived sulfate contributions to arc lavas and that the positive δ34S signature of the lavas results from crustal assimilation10.

The role of slab fluids in delivering sulfur species to the mantle wedge is central to this debate. Experimental results suggest that slab-derived aqueous fluids are an effective agent for transporting sulfur from the slab to the mantle wedge11,12. In addition, some studies predict that sulfates are likely the dominant sulfur species in slab-derived fluids9,13. On the other hand, sulfate is relatively rare in high-pressure (HP) rocks13,14,15,16,17,18, and experimental studies have proposed that reduced sulfur species are dominant in slab fluids11. Furthermore, in situ measurements of the δ34S compositions of sulfides from HP eclogites and serpentinites reveal significant isotopic heterogeneity and complicated sulfur behavior during slab metamorphism and metasomatism13,14,15,16.

Clearly, large gaps in our knowledge of the speciation, flux, and isotopic composition of sulfur in slab fluids remain. Understanding these is of utmost importance for addressing slab–arc sulfur recycling, and has global geochemical significance for deciphering the redox state of the mantle2 and constraining the formation of arc-related ore deposits12. Direct examination of devolatilization pathways in exhumed HP rocks is essential to provide independent new perspectives critical to resolving this debate, as it provides the necessary field-based evidence for the sulfur redox state and δ34S signature of fluids released from subducted slabs.

Sulfur is transported into the subduction zone by sediments, variably altered oceanic crust (AOC), and hydrated slab mantle (serpentinites)19,20,21,22. Sulfides are commonly observed in exhumed fragments of the oceanic lithosphere such as eclogites, blueschists, HP-metapelites, and serpentinites, as well as related HP veins13,14,15,16,17,18,23. Such vein systems represent fossilized pathways for channelized flow of dehydration-related slab fluids and, thus, directly record fluid geochemical signatures17,24,25. Consequently, the study of HP vein–rock systems provides important information regarding sulfur behavior during slab dehydration and fluid transfer17. Isotopic constraints on S-bearing HP rocks and veins linked to the sequence of slab dehydration allow quantification of sulfur release during subduction of oceanic lithosphere.

Here, we report bulk-rock and in situ sulfur isotope compositions for sulfide-bearing HP rocks and veins from the late Paleozoic southwestern Tianshan (ultra-)high-pressure/low-temperature ((U)HP/LT) metamorphic belt (China). The sulfides in these HP rocks and veins17 provide an exceptional window into the fate of subducted sulfur. Analytical data and thermodynamic calculations point to low sulfur concentrations in slab fluids, which have negative δ34S values and are dominately composed of reduced sulfur species. Hence, we determine modest slab-to-arc sulfur transport, and find neither significant slab sulfate flux to the mantle wedge nor a direct link between slab-derived sulfur and the positive δ34S signature of arc settings.

Results

Sample background

The Tianshan (U)HP/LT terrane is an example of deeply buried, uppermost oceanic crust covered by km-thick trench metasediments26. We selected 10 pristine samples from different sequences within a subducted oceanic slab (2 metapelites, 5 metabasites, 3 serpentinites, Supplementary Table 1) to obtain a general picture of sulfur reservoirs. Mineral assemblages suggest that one metapelite reached low blueschist-facies conditions (300–400 °C, 1.0–1.5 GPa), whereas the other metapelite (garnet–glaucophane-bearing) reached blueschist-facies conditions (400–500 °C, 1.5–2.0 GPa)27. Metabasites with oceanic affinity are eclogites and blueschists (lawsonite relic identified) with peak metamorphic conditions clustering around 540 °C and 2.5 ± 0.2 GPa26. Sulfides in all HP metapelites and metabasites are mainly pyrite with minor amounts of chalcopyrite and bornite17. Sulfide occurs both as inclusions in garnet and in the matrix. Matrix pyrite contains garnet, omphacite, glaucophane, lawsonite and dolomite inclusions (Supplementary Table 1). Serpentinites, composed mostly of antigorite and magnetite with minor pentlandite and millerite, are considered to be part of the subducted slab that underwent UHP metamorphism (∼520 °C, >3.0 GPa)28 in the Tianshan.

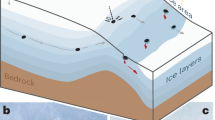

In addition, three representative sulfide-bearing dehydration-related veins in blueschists or eclogites were investigated to reconstruct the sulfur behavior in subduction fluids derived from different sources (Fig. 1). Vein_1 (JTS) consists of a well-studied wallrock–selvage–vein system25,29 formed by fluid–rock interaction during prograde metamorphism (Fig. 1a). The wallrock (host blueschist, garnet–glaucophane-dominated) along the vein traverse was progressively altered to an eclogite selvage (garnet–omphacite-dominated) and a blueschist–eclogite transition zone due to reaction with an external fluid (Fig. 1a). The wallrock–selvage–vein system equilibrated at peak metamorphic conditions of ∼510 °C and 2.1 GPa29. Sr and Ca isotope compositions trace the fluid source to seawater-altered lithospheric slab–mantle and/or oceanic crust25. Vein_2 (L1422) is a 2-cm-wide dolomite–quartz–epidote-dominated vein crosscutting a massive host blueschist (Fig. 1b). Similar to Vein_1, the blueschist–eclogite transition zone and eclogite selvage formed due to interaction with Ca-rich fluid along the conduit (Fig. 1b). The similar structure, mineral assemblages, and compositions of Vein_1 and Vein_2 indicate that they formed at similar P–T conditions. Vein_3 (L1013) is a 1–3 cm wide dolomite–quartz–epidote-dominated vein cutting massive eclogite (Fig. 1c). Occurrences of high-pressure minerals such as omphacite and rutile in Vein_3 along with the observation that no reaction halo occurs between the vein and host eclogite (Fig. 1c) indicate that the vein also formed at eclogite-facies conditions. Considering most eclogite samples in the Tianshan HP metamorphic belt were exhumed from ∼80 km depth26, all three HP veins are thought to represent the fluid activity that took place at 70–90 km depths in the subduction zone.

a Sample JTS containing host blueschist (HB), blueschist–eclogite transition zone (BETZ), eclogite selvage (ES) and vein. Six drill samples (JTS-B, -D, -E, -G, -H, -I) along the traverse were taken for petrological investigation and chemical measurements. b HB–BETZ–ES–vein system L1422. Nine drill cores (see numbers) along the profile were investigated in this study. Petrological features of underlined drill samples are shown in Fig. 2. c Eclogite–vein sample L1013. Mineral abbreviations: dolomite (Dol), epidote (Ep), omphacite (Omp), pyrite (Py), quartz (Qz), and rutile (Rt).

Sulfides are found in all vein samples. In sample JTS, pyrite is the dominant sulfide inclusion in garnet, but pyrrhotite dominates in the matrix (Fig. 2a, b). This demonstrates a pyrite–pyrrhotite transition during garnet growth due to changing sulfur fugacity–oxygen fugacity (fS2–fO2) conditions associated with fluid metasomatism. Sulfide in the vein is mostly pyrite but also includes minor pyrrhotite (Fig. 2c). Along the traverse of samples L1422, sulfide (mainly pyrite) abundances increase toward the vein. The Co–Ni element distribution maps (Method 1) reflect distinct differences between host blueschist pyrite (Fig. 2d–f) and selvage–vein pyrites (Fig. 2g–i). Both selvage and vein pyrites display multiple growth generations (Fig. 2g–i). In sample L1013, Co–Ni element distribution maps and contents show core–rim textures in both eclogite (Fig. 2m) and vein pyrite (Fig. 2n–p).

a–c Sulfides in sample JTS. Sulfides in garnet are mainly pyrite with minor pyrrhotite and chalcopyrite, whereas the matrix contains mainly pyrrhotite with minor chalcopyrite and pyrite in both the host blueschist (a) and blueschist–eclogite transition zone (b). d–i Photomicrographs and Co–Ni maps of pyrite in the host blueschist (d–f), eclogite selvage (g–i), and vein (j–l) in sample L1422. m–p Pyrite, δ34S values, and Co–Ni maps in sample L1013. Trace-element concentrations (µg g−1) of pyrite are given in the white rectangles. δ34S values and Co–Ni maps in vein pyrite (n–p) suggest two growth generations. All photomicrographs (except Co–Ni maps) use superposed transmitted and reflected light to simultaneously image silicates and sulfides. Mineral abbreviations: chalcopyrite (Ccp), dolomite (Dol), epidote (Ep), garnet (Grt), glaucophane (Gln), omphacite (Omp), phengite (Ph), pyrite (Py), pyrrhotite (Po), quartz (Qz), and rutile (Rt). Scale bar: 200 μm.

In most samples, fine fractures were occasionally observed surrounding sulfide grains, reflecting rigidity contrasts between sulfide and matrix minerals. These fractures are usually filled with albite + magnetite + calcite ± chalcopyrite ± barite due to late-stage fluid infiltration, accompanying variable retrogression of neighboring omphacite and glaucophane. Sulfate and magnetite were observed only in these late-stage, retrograde fractures.

Bulk-rock sulfur geochemistry of different lithologies

The 10 HP rocks and 15 representative subsamples from two host–selvage–vein systems (JTS and L1422) were analyzed for their whole-rock sulfur contents ([S]WR) and δ34S compositions (δ34SWR, Method 1). The metapelites have [S]WR = 1101–5612 µg g−1 and negative δ34SWR of −12 to −7.9‰ (Fig. 3, Supplementary Table 1) and the metabasites have [S]WR = 841–3978 µg g−1 and a range in δ34SWR of −7.2 to +3.6‰, averaging −2.7‰ (n = 5). In contrast, all measured serpentinites ([S]WR = 124–422 µg g−1) have positive δ34SWR values (+3.6 to +12‰), signifying high-temperature water-rock interaction during oceanic serpentinization30. These results are similar to unmetamorphosed oceanic lithosphere19,20,21,30 and suggest that the main slab sulfur reservoirs have distinct δ34SWR compositions, which are generally consistent with previous studies of exhumed slab rocks14,15 (Fig. 3). Sulfur in nearly all samples is present as reduced S2− or S−, whereas S6+ contents are very low ([S6+]/[S]WR < 0.06). Only one serpentinite sample has more sulfate than sulfide ([S6+]/[S]WR ≈ 0.89).

Errors (2σ) of δ34SWR and SWR calculated from measurement reproducibility are less than the symbol size. Sulfur isotope values of HP Tianshan (TS) rocks are from this study, Franciscan (FS) eclogites and blueschists from ref. 10, high-pressure serpentinites of the Voltri Massif (VM, Italy) from refs. 47,48, high-pressure serpentinites of the Cerro del Almirez (CA, Spain) from ref. 21, and the mantle value (−0.91 ± 0.50‰) from ref. 45. The shaded area indicates δ34S range of metabasites, which is comparable to the mantle value. Source data are provided in Supplementary Data.

Sulfur geochemistry in HP vein systems

In the host blueschist to blueschist–eclogite transition zone of Vein_1 the [S]WR varies between 698 µg g−1 and 841 µg g−1, but toward the vein and vein-like eclogite selvage, the [S]WR increases up to 2183 µg g−1 (Fig. 4a). In contrast, the δ34SWR values decrease gradually from +0.43‰ to −0.98‰ toward the vein (Fig. 4a). The in situ δ34S values of sulfides in garnet show little variation; however, matrix sulfides display a decreasing trend from host rock toward the vein (Fig. 4b; Method 1). The local bulk isotopic compositions of sulfides (δ34Ssulfide), calculated using mean in situ δ34S values of individual sulfides (Fig. 4b) and their mineral volume ratios (Supplementary Fig. 1), have a narrow range of +0.34–+0.72‰ (mean +0.60‰) in the garnet along the traverse (Fig. 4b). This reflects shielding of the sulfide inclusions by garnet during fluid–rock interaction. In contrast, the δ34Ssulfide in the matrix decreases gradually from about 0.00‰ to −1.35‰ toward the vein (Fig. 4b). The δ34SWR and δ34Ssulfide display similar decreasing trends along the traverse. Vein sulfides have uniform δ34Ssulfide values of about −1.0‰ (Fig. 4b).

a Calculated [S]WR and δ34SWR compositions based on measured whole-rock (WR) compositions of acid volatile sulfide (AVS), chromium reducible sulfide (CRS) and sulfate (Method 1). Rectangle height indicates sulfur content, and underlined δ34S values above rectangles refer to calculated δ34SWR compositions. Sulfate contents are mostly below the detection limits or very low. b In situ δ34S compositions of sulfides along the profile. Sulfides occurring as inclusion in garnet are denoted by circles, matrix sulfides by squares, and vein sulfides by diamonds. Bold black lines refer to calculated δ34Ssulfide values (see also Supplementary Fig. 1). Vein sulfides include two types of pyrite. Texture investigation indicates that one type (orange diamonds) is late-stage with δ34S around −0.21‰, which was not included in the calculation for JTS-G’ and JTS-H. The vertical bars show the analytical errors calculated after propagating the within-run and external uncertainties of standard measurements. Red stars show δ34SWR compositions from a. Mineral abbreviations: chalcopyrite (Ccp), garnet (Grt), pyrite (Py), and pyrrhotite (Po). Source data are provided in Supplementary Data.

The host blueschist of Vein_2 has the lowest [S]WR of 604 µg g−1 and δ34SWR values of −11.0‰ (Fig. 5a, Supplementary Table 1). Within the blueschist–eclogite transition zone, both [S]WR and δ34SWR increase and have relatively narrow ranges of 1465–1854 µg g−1 and −8.1 to −7.7‰, respectively. These values increase further to [S]WR = 2167–2848 µg g−1 and δ34SWR = −1.7 to −0.9‰ in the eclogite selvage (Fig. 5a). The vein has the highest [S]WR (9251 µg g−1) and δ34SWR value (−0.7‰) (Fig. 5a). In situ pyrite δ34S compositions (Fig. 5b–d) are consistent with the bulk-rock analyses. Pyrite in the host blueschist has Ni-rich cores with negative δ34S values of −16.0 to −10.1‰ (weighted mean −12‰) and Ni-poor rims with δ34S values of −7.7 to −5.0‰ (weighted mean −7‰) (Fig. 5b). The vein and selvage pyrites show uniform core–mantle–rim textures recorded by Co–Ni element distribution maps (Fig. 2g–l): a Ni-rich core with modest enrichment in Co (Py_1, Co: 367 µg g−1, Ni: 1277 µg g−1, δ34S: +7.4 to +8.6‰); a massive Co-poor and moderately Ni-enriched mantle (Py_2, Co: 174 µg g−1, Ni: 813 µg g−1, δ34S: +0.9 to +4.0‰); and a thin Co-rich and Ni-poor rim (Py_3, Co: 3803 µg g−1, Ni: 229 µg g−1, δ34S: −6.7 to −2.3‰) (Fig. 5c, d). These three pyrite generations with variable Co–Ni contents and δ34S values likely represent three stages of fluid infiltration.

a Calculated [S]WR and δ34SWR compositions from bulk-rock analyses along the traverse of sample L1422. Errors of δ34SWR and SWR calculated from analytical reproducibility are smaller than the symbols used. HB host blueschist, BETZ blueschist–eclogite transition zone, ES eclogite selvage. b Histograms of in situ pyrite δ34S values in the HB, ES, and vein (sample L1422, red lines refer to the δ34SWR values). c Histograms of pyrite δ34S values in the sample L1013. Source data are provided in Supplementary Data.

The vein pyrite of Vein_3 has a thick Co-poor but Ni-rich core (δ34S = −8%) and a thin Co-rich but Ni-poor rim (δ34S = −5‰) (Figs. 2n–p, 5f). In contrast, pyrite in the host eclogite contains a Co–Ni-rich core with MORB-like δ34S values (−1.3 to −0.5‰), but its rim is analogous to the vein pyrite core in Co–Ni–As contents, δ34S values (about −8%), and mineral inclusions (omphacite and rutile) (Figs. 2m, 5e). This indicates that the vein-forming fluid also altered the immediate eclogite and caused pyrite regrowth surrounding the cores.

Sulfur concentrations in aqueous fluids from DEW modeling

The sulfur concentration in fluids ([S]fluid) is the most important factor determining the slab sulfur output, as aqueous fluids are thought to be the major agent for slab–mantle sulfur transfer11. We use the DEW (Deep Earth Water) model31,32 to calculate subduction zone [S]fluid (Method 2), as this allows a quantitative prediction of speciation and solubilities in fluids at upper mantle conditions. Because sulfur solubility and speciation is redox-dependent, an estimate of the fO2 is required prior to calculation. The fO2 of subducted AOC is FMQ + 1 (ref. 33) (one log unit above Fayalite–Magnetite–Quartz buffer) at the trench and decreases gradually with increasing depth (below FMQ at depths corresponding to eclogite-facies conditions)17, as generally reducing fluids (<FMQ) are generated17,34. In contrast, the redox state of slab serpentinite is more complicated (either above or below FMQ) and is suggested to vary due to different degrees of pre-subduction serpentinization35, producing both highly oxidizing or reducing fluids35. Dehydration of incompletely serpentinized rocks (usually those beneath oceanic crust) in which awaruite is present produces reducing H2-bearing fluids, whereas deserpentinization of completely serpentinized rocks (usually those once directly exposed to seawater) in which awaruite is absent produces oxidizing fluids in the subduction zone35. The former is applicable in our case, as the majority of slab mantle occurs beneath oceanic crust and is not fully serpentinized. For details regarding slab fO2 estimates see the Supplementary Note 1.

Following a typical subduction geothermal gradient36, [S] and its speciation in slab fluids were calculated for given fO2 conditions at 60 km (FMQ), 75 km (FMQ), 90 km (FMQ-1), 120 km (FMQ-2), and 150 km (FMQ-3) for subducted sediments and oceanic crust, whereas fO2 was 1–2 log units higher for serpentinites at the corresponding depths (Supplementary Table 2). Results show that [S]fluid is largely dependent on P–T conditions (Fig. 6a) and is generally very low (<0.1 molal), similar to previous thermodynamic modelling37,38,39. Critically, however, our results reveal a distinct [S]fluid peak (0.20–0.35 molal) at ∼3.0 GPa, regardless of whether the fluids equilibriated with metasediments, metabasalts or serpentinites (Fig. 6a), indicating a sulfur release pulse at ∼90 km depth. Sulfur species are fO2-dependent and dominated by reduced aqueous H2S and HS− at all model subduction zone P–T–fO2 conditions (Supplementary Fig. 2), consistent with our natural observations. Oxygen fugacity variations of ±1 unit will only change the proportion of sulfur species in the fluid (e.g., slight increases of SO42− and/or HSO4− abundances), but will not cause significant [S]fluid changes (Supplementary Fig. 2).

a [S]fluid derived from different lithologies in the subduction zone calculated by DEW model. Numbers in brackets refer to oxygen fugacity (relative to FMQ buffer) used at certain P–T conditions. Shaded areas indicate [S]fluid variations if fO2 changes within ±1 unit. Sulfur species and proportions at every point are given in Supplementary Fig. 2. b Depth‐dependent water flux released from global subducting slabs49. Water flux is calculated every 10 km between 50–100 km. For example, about 0.91 × 1014 g yr−1 H2O is dehydrated from the upper volcanic layer over the depth interval 80–90 km (corresponding to X-axis 90 km). Source data are provided in Supplementary Data.

Hydrothermal sulfur isotope fractionation

Effects of sulfur isotope fractionation during hydrothermal processes are largely influenced by pressure, temperature, fO2 and the pH of the fluids40,41. We thermodynamically calculated fO2–pH diagrams42 (Fig. 7a–d) (Method 3) for different P–T conditions to reveal δ34S fractionation in subduction zones. Our DEW calculations suggest that slab fluids are generally alkaline and the pH value ranges from neutral (pHn) to pHn + 2, consistent with previous work43. According to fO2 (Supplementary Table 2) and pH estimates of subduction zone fluids, all the fO2–pH conditions plot in fields dominated by the species H2S or HS− (yellow area, Fig. 7a–e), in agreement with DEW results (Supplementary Fig. 2). The fO2–pH diagram indicates limited sulfur isotope fractionation (<3‰) at different P–T conditions along the subduction interface (Fig. 7a–d). In particular, at the vein-forming P–T conditions of this study, fO2 (<FMQ)17 and pH range (pHn to pHn + 2) suggest sulfur isotope fractionations <1.3‰ (Fig. 7e). In addition, precipitation styles of sulfide in hydrothermal settings (closed- or open-system) may also influence the sulfur isotope fractionation41. In both closed and open systems, theoretical calculations (Method 3) display <1‰ fractionation if pyrite precipitated from H2S−dominated fluids at 550 °C (Fig. 7f, g), consistent with previous calculations for subduction conditions14,15.

a–d Influence of fO2 and pH on the isotopic compositions of pyrite precipitated from hydrothermal fluids at ionic strength I = 1.0 and δ34S∑S = 0‰, at specific P–T conditions of various depths along the subduction interface. The squares (metasediment), circles (metabasalt) and diamonds (serpentinite) represent estimated fO2 conditions (Supplementary Note 1) and calculated pH values from the DEW model. The rectangles denote slab fO2–pH conditions from ref. 43. The color scales (‰) refer to δ34S contours as a function of fO2 and pH, and the gray solid line indicates the contour with no sulfur isotope fractionation. e, δ34S fractionation modelling at P–T conditions of the vein samples studied here. f–g Sulfur fractionation calculation plots of FeS2 precipitation from fluids at 550 °C in a closed system (f) and an open system following a Rayleigh fractionation model (g). Solid lines denote the fluid phase, whereas the dashed lines represent the precipitated phase. The orange and blue lines represent the results for H2S- and SO42−-fluids, respectively. Initial δ34Sfluid is 0‰. The shaded area indicates the expected sulfur fraction of sulfide precipitation under a channelized fluid flux. Source data are provided in Supplementary Data.

δ34S values of fluids from different slab reservoirs

The small sulfur isotope fractionation between sulfides and equilibrated H2S-bearing fluids40,41 (Fig. 7) demonstrates that the δ34S values of vein sulfides approximately represent the fluid δ34S composition and can be used as a tracer for source discrimination. Our measured negative δ34SWR values of −12 to −8‰ in metasediments (Fig. 3) are similar to their protoliths, the young marine sedimentary rocks (Phanerozoic) that mostly have δ34S values of −24 to −8‰ due to the presence of biogenically produced sulfide19,44. It is suggested that sulfide in sediments retains its δ34S characteristics during subduction metamorphism13 and that metasediments may act as a negative δ34S reservior in subducting slabs. The vein pyrite core with negative δ34S (−8‰) in sample L1013 (Fig. 2n) thus likely represents the δ34S signature of fluids derived from the abundant subducted metasediments in the Tianshan HP belt16,26.

Pristine oceanic crust is typically within the range of the average mantle δ34S of −0.91 ± 0.50‰45. However, pre-subduction seafloor processes lead to considerable δ34S heterogeneities in the upper crust (Fig. 3, Supplementary Table 1). For instance, microbial sulfate reduction during seafloor alteration moves the δ34S of the volcanic section toward negative values (average −6‰), some as low as −19.5 to −45‰22. The blueschists studied herein with more negative δ34SWR (−15‰ and −11‰, Supplementary Table 1) may record this microbially produced δ34S heterogeneity. In contrast, sulfide grains in some eclogites from the Alps and New Caledonia show positive δ34S compositions (+7‰ and +12‰)15. However, these sulfides are associated with blueschist/greenschist retrogression15, which may record the oxidizing fluids at shallow depth that usually cause retrogression of exhumed eclogites/blueschists17. The positive δ34S may originally come from seawater hydrothermal alteration, or represent the fluids derived from serpentinite dehydration (see below). Therefore, although pre-subduction seafloor processes cause negative or positive δ34S shifts in metabasites, bulk-rock geochemistry shows that many mafic eclogites and blueschists still retain their mantle-like sulfur isotope signature throughout HP metamorphism (Fig. 3). Furthermore, the lower crust (dike and gabbro) retains its mantle-like δ34S values as well46. Consequently, the δ34S of vein sulfides from sample JTS (−1‰) is interpreted to record the sulfur isotope signature of fluids released from the oceanic crust (the dike and gabbro part, in particular). This fluid source interpretation is consistent with the δ34SWR of the host blueschist (+0.43‰, Supplementary Table 1) and trace-element contents29 and Sr–Ca isotope compositions25 of the vein.

Serpentinites are quite heterogeneous in [S], S6+/∑S, and bulk-rock δ34S (refs 21,30), and are readily influenced by late-stage fluids during exhumation23. Our three measured Tianshan UHP serpentinites all have positive δ34SWR compositions, consistent with bulk-rock results for Voltri Massif serpentinites21,47,48 (Fig. 3) and in situ sulfide δ34S compositions from Corsican serpentinites14. We suggest that variably serpentinized slab mantle beneath oceanic crust is characterized by positive δ34S compositions as a result of sulfide addition via sulfate reduction at high-temperatures30 during partial serpentinization. Thus, the Py_1 with positive δ34S (+8‰) in vein sample L1422 (Figs. 2k, 5d) is interpreted to reflect the characteristic δ34S composition of fluids derived from the partly serpentinized slab mantle. The pyrite mantle (Py_2) with positive but decreasing δ34S (from +4.0 to +0.9‰) of vein sample L1422 (Figs. 2k, 5d) likely represents fluid mixing with an increased AOC contribution relative to slab serpentinites. The negative δ34S (−5‰) of thin rims on vein pyrite (Figs. 2n, 5d) with the sharply increasing Co concentrations (Fig. 2k, o) may represent retrograde oxidized fluids during exhumation17, as evidenced by the surrounding fractures with albite-calcite-magnetite infillings and neighboring retrogression of matrix omphacite.

Discussion

Thermodynamic modelling shows that at subduction zone P–T–fO2–pH conditions sulfur in fluids is dominated by the reduced H2S and HS− species, whereas sulfate species (e.g. SO42−, HSO3−) are rare (Supplementary Fig. 2). This is consistent with our petrological evidence for the occurrence of sulfide, but not sulfate, in the veins (Figs. 1–2), the very low sulfate concentrations in rocks and veins (Fig. 4a; Supplementary Table 1), and previous experimental results11. If slab fluids are dominated by sulfate as some recent studies propose13, several predictions follow. First, the oxidizing fluid will produce a redox gradient in the immediate wallrock, but this is not recorded in the selvages we examined. Second, reduction from S6+ to S2− will cause oxidation within the immediate rock and vein (in particular during vein crystallization) in the form of hematite or magnetite17, which, however, are absent from the veins or selvages. Third, complete sulfate–sulfide transformation will produce very high δ34S values in the product phases, which is also not observed in the veins or selvages. The sulfate introduced during pre-subduction hydrothermal seafloor alteration20,21,30 may have been lost or converted to sulfide at early stages of subduction, for example, at fore-arc depths10,12. Thus, we conclude that the dehydration-related slab fluids likely transport reduced sulfur species such as aqueous H2S and HS− at sub-arc depths.

Mass-balance calculations were used to estimate the sulfur influx (FS) and outflux (fS) of subduction zones, as well as their δ34S values. The sulfur input estimate was computed (Method 4) based on the average [S] and δ34S compositions of our best current understanding of oceanic lithosphere stratigraphy (Supplementary Fig. 3, Note 2) in combination with the global length of subduction zones and their average convergence rate, sequence thickness, and density. The resulting subduction zone sulfur influx is estimated to be 4.65 × 1013 gram per year (g yr−1) with a bulk negative δ34S value of −3.60‰. Gabbro (49%) and sediment (23%) are two important sulfur reservoirs (Fig. 8a), whereas serpentinite is insignificant due to its low [S]. This influx is slightly lower than, but generally within the same order of magnitude of, previous estimates2,19,21,22 (Fig. 8b).

a Subduction sulfur input and output (30–230 km) categorized by source. b Comparison of subduction sulfur input vs. output. Sulfur influx and outflux estimations are given in the inset table. Labeling of estimates refers to source data (see inset), E to Evans2; H to Hilton et al.50; K to Kagoshima et al.78; L to this study; W to Wallace51; and M to Canfield19, Alt and Shanks22, and Alt et al.21. Uncertainties of estimates indicated with dashed rectangles. No errors are shown if they were not provided in the original study. Note that there is no output data for M.

The sulfur output can be calculated from the product of [S]fluid and the fluid fluxes from the dehydrating slab. Previous thermodynamic constraints37,38,39 on [S]fluid predict a rather low proportion of H2S (<0.01 mol.% in equilibrium with H2O + pyrite + pyrrhotite)38,39. This low [S]fluid, in turn, predicts negligible slab sulfur output (fS/FS < 1%), which is not compatible with the high sulfur contents observed in arc settings. Based on our novel [S]fluid results from the DEW calculations (Fig. 6a) and depth-dependent fluid fluxes from the dehydrating slab49 (Fig. 6b), a total sulfur outflux (Method 5) of 2.91 × 1012 g yr−1 (6.3% of FS) is estimated via fluids derived from the subducting slab between 30–230 km (Fig. 8a). The sheeted dikes (31%) and the upper volcanic layer (26%) contribute most of the sulfur release, but the sediment (15%) and the lower volcanic layer (15%) are also important (Fig. 8a). This sulfur outflux from the slab is about 1/5 to 1/3 of the sulfur output estimates from arcs2,50,51 (Fig. 8b).

Importantly, our sulfur output estimate shows a major sulfur release of 2.46 × 1012 g yr−1 (5.3% of FS) to the mantle wedge at depths of 70–100 km (Fig. 9) due to both elevated [S]fluid (Fig. 6a) and released H2O flux49 (Fig. 6b). The volcanic layers, dikes, gabbro, and sediments contribute to the major sulfur release at this depth interval (Fig. 8a). This sulfur release window coincides with pyrite-to-pyrrhotite breakdown12 (releasing H2S) and the major slab fluid release (∼32% H2O/H2Ototal)49, which subsequently acts as the trigger for partial melting of the mantle wedge and ultimately arc magmatism25,52,53. The release of slab sulfur is minor at other depths (Fig. 9). The DEW model may underestimate [S]fluid due to unknown sulfur species. In addition, considering the uncertainties on the thermodynamic data (±0.3 to ±0.5 of logK)31, the slab sulfur loss estimate may extend to a maximum of ∼20%. This is comparable to the estimate obtained from natural rocks and experiments (30%, Supplementary Note 3), and previous estimates (8–18%, Fig. 8b) from arcs2,50,51.

a Schematic lithologic succession of typical subducted oceanic lithosphere. The bold arrows refer to channelized fluid flow, and the dashed rectangle refers to the sequences of this case study in the Tianshan. b Estimated sulfur flux (arrow sizes represent the relative sulfur amounts) and isotope compositions released from the subducting slab at different depths via fluid flow. Inset circle shows the key parameters during net δ34S calculation of slab fluids to sub-arc mantle, such as global H2O flux, sulfur concentration and isotopic composition of fluids derived from different sequences of the subducting slab. fS/FS ratio of 20% is the maximum value from DEW results. Numbers in ellipsoids refer to bulk sulfur isotope compositions in reservoirs of subduction settings (data sources see text). Red stars represent the depths of metasediments, metabasites (including veins) and serpentinites in this study formed in the subduction zone. Not to scale. Source data are provided in Supplementary Data.

Knowing [S]fluid (Fig. 6a) and water fluxes49 (Fig. 6b) liberated from slab sequences as well as the δ34Sfluids of sediments (−8‰), oceanic crust (−1‰) and serpentinites (+8‰), mass-balance calculations (Method 5) predict a δ34S value of slab fluids of −1.8 ± 3‰ at depths of 70–100 km. Both the gradually decreasing δ34SWR and δ34Ssulfide values (sample JTS, Fig. 4a) and the trend of increasing δ34SWR values within the studied profile (sample L1422, Fig. 5a) provide clear evidence for isotope exchange during fluid–rock interaction, despite rapid fluid transport rates24,25. The sulfur isotope composition of channelized fluids generated in the lower parts of a slab could be slightly altered within the upper parts during fluid transport. Assuming a 10% sulfur isotopic contamination rate by sediment and 20% by oceanic crust for underlying sulfur sources, the net δ34S value is calibrated to −2.5 ± 3‰ at depths of 70–100 km (Fig. 9). If δ34Sfluids values from different reservoirs are kept constant at different depths, δ34S of slab fluids at shallower depths remains negative but shifts to positive at greater depths, and a net δ34S of −2.1‰ is obtained for slab fluids between the whole 30–230 km (Fig. 9). Regardless of flux uncertainties, we emphasize that the negative δ34S value of slab fluids is robust and insensitive to a range of different model scenarios (Method 6), including thick serpentinized slab-mantle scenarios54, which may supply more fluids with positive δ34S values.

This study provides the first comprehensive and quantitative view of the flux and isotope compositions of sulfur-bearing slab fluids, which likely mirror the slab sulfur contributions to arcs25,55. We show that dehydration-related fluids transfer modest amounts of sulfur (6.4% of total subducted sulfur, up to 20% maximum) from the slab to the mantle wedge. This maintains elevated sulfur contents of the mantle source for arc magmas (250–500 µg g−1)6,7 in comparison to MORB (80–300 µg g−1)56. Additional significant release by, for example, slab melting is unlikely, as [S] in melts is much lower than in aqueous fluids (DSfluid/melt usually >200)11. This slab-arc sulfur cycle is operated by fluid-mediated H2S and/or HS− transport with negative δ34S composition, which has no direct links to the high oxygen fugacity and heavy δ34S signature observed in arc volcanic rocks.

Our work also sheds further light on the nature of arc magmas. The reason for the higher fO2 of arc magmas57,58 relative to MORBs is still debatable. Intraoceanic or rare continental arcs, like those of the Western Pacific, may record flux melting; mantle peridotites with elevated fO2 values in these settings have been thought to be influenced by slab-derived oxidizing agents59,60. In contrast, continental arcs, like those of the Eastern Pacific arcs where crust thickness may modulate the melting degree61, may represent a complicated melting mode involving decompression and mantle peridotite that is not necessarily oxidized59,62. Direct comparisons of Western and Eastern Pacific arcs may be challenging due to their different melting modes and arc maturity59,60. The P–T evolution of the Tianshan eclogites (representing cold/old subducted oceanic slab) corresponds more closely to the thermal structure of subduction zones beneath the Western Pacific arcs59. However, our finding of negligible sulfate in the slab fluids indicates that slab SO42− was unlikely to be the main oxidizing agent during South Tianshan Ocean subduction. In such environments, the high fO2 of sub-arc mantle may instead result from addition of slab H2O and CO2 (refs 63,64), instead of oxidized sulfur species. Processes including incorporation of H2 into orthopyroxene63 and the formation of diamond64 and CH4 (ref. 65) in the mantle wedge may produce oxidized melts that elevate the fO2 of Western Pacific arc magmas.

The calculated negative δ34S (−2.5 ± 3‰) released from the subducted slab (Fig. 9) contrasts with the positive δ34S values found in the inclusions of Western Pacific arc rocks4,5,8. In general, the mantle wedge should have mantle-like δ34S values of ∼0‰. Therefore, the positive δ34S signature in arc-related rocks requires additional sulfur sources or processes for 34S enrichment. Volcanic degassing effects on melt δ34S are highly dependent on redox state66,67. But even under oxidizing conditions (>FMQ + 2), increases in melt δ34S caused by degassing are modest (∼1.5‰)66. Therefore, the negative-to-positive shift in the δ34S composition of melts must happen as part of the partial melting processes, such that significant sulfur isotope fractionation accompanies the melt oxidization. For example, 32S may be scavenged into surrounding mantle to form sulfides while H2 is incorporated into orthopyroxene63, producing 34S-rich sulfate in oxidizing melt and finally isotopically heavier arc magmas. Thus, further studies will be necessary to assess the processes that may lead to the positive δ34S compositions in arc magmas.

Our comparison of subduction input with output fluxes indicates that most of the sulfur (>80%) with negative δ34S values (<−3.7‰) is retained in the descending slab and recycled to the deep mantle (Fig. 9). This may have resulted in a progressive 34S-enrichment of Earth’s surface sulfur reservoirs19, and can explain the negative δ34S values of alkaline magmas related to ocean island basalts (OIBs) since the Phanerozoic68.

Methods

Analytical methods

Bulk-rock sulfur contents and isotope compositions were measured at the Geological Institute at the Freie Universität Berlin. Extraction of the bulk-rock sulfur was performed by extracting the acid volatile sulfide (AVS), chromium reducible sulfide (CRS), and the sulfate fraction69. Sulfur isotope measurements of AVS, CRS, and sulfate fractions were done on a Thermo Fisher Scientific MAT 253 mass spectrometer combined with a Eurovector elemental analyzer. The [S]WR of individual samples were calculated by summing sulfur amounts of measured AVS, CRS, and sulfate. The δ34SWR was calculated by measured δ34S values of AVS, CRS, and sulfate in combination with their amounts. In situ sulfur isotopes of sulfides on epoxy discs were analyzed via Secondary Ionization Mass Spectrometry (SIMS) using a Cameca IMS 1280 instrument located at the Swedish Museum of Natural History, Stockholm, Sweden (NORDSIM facility)70 for sample JTS and at the Institute of Geology and Geophysics, Chinese Academy of Sciences (IGGCAS, Beijing, China)71 for other samples. Measurements were conducted over a rastered 10 × 10 μm area using a 133Cs+ primary beam with 20 kV incident energy (10 kV primary, −10 kV secondary) and a primary beam current of ∼1.0 nA. All δ34S results are reported with respect to the V-CDT standard72. Detailed descriptions of δ34S measurement parameters and standard references are given in the Supplementary Note 4. Elemental Co and Ni X-ray maps of pyrite were made in wavelength-dispersive spectrometer mode by electron microprobe (CAMECA SXFive FE) at the IGGCAS. An acceleration voltage of 20 kV, beam current of 100 nA, 3–5 μm pixel size, and dwell time of 50 ms were used. In situ trace-element analyses by laser ablation inductively-coupled plasma mass spectrometry of sulfides were made on thin sections in the GeoZentrum Nordbayern of the University Erlangen–Nürnberg, Erlangen, Germany.

DEW calculation of sulfur concentration in fluids

The DEW model31,32 enables the calculation of reaction equilibrium constants involving minerals, aqueous inorganic and organic ions, complexes, and neutral species. These equilibrium constants combined with the EQ3 fluid speciation code73 can be used to develop an aqueous speciation and solubility model at high-pressure and temperature conditions. The DEW model has been successfully applied to predict organic species, diamond formation, and nitrogen cycling in subduction zones74,75. EQ3 computes the equilibrium aqueous speciation of a fluid in equilibrium with certain mineral assemblages at specified temperature, pressure, and oxygen fugacity. We calculated sulfur concentrations and speciation (Fig. 6a, Supplementary Fig. 2) in slab fluids at different P–T conditions along a typical subduction geothermal gradient36, modeling cases at 60 km (2 GPa, 400 °C), 75 km (2.5 GPa, 550 °C), 90 km (3 GPa, 700 °C), 120 km (4 GPa, 770 °C), and 150 km (5 GPa, 800 °C). The fO2 of subducted oceanic crust decreases with increasing depths and increasing capacity of Fe3+ in garnet and pyroxone17. Considering mineral assemblages in subduction zone rocks17,76, fO2 was set at ΔFMQ + 1 (30 km), ΔFMQ (60 and 75 km), ΔFMQ-1 (90 km), ΔFMQ-2 (120 km), and ΔFMQ-3 (150 km) for subducted oceanic crust (garnet + clinopyroxene + pyrite/pyrrhotite ± lawsonite/kyanite ± carbonate/graphite ± quartz/coesite) and overlying metasediment (muscovite + quartz/coesite + pyrite/pyrrhotite ± chlorite ± paragonite ± talc ± garnet ± clinopyroxene ± lawsonite/kyanite ± carbonate/graphite). For slab serpentinite (antigorite + orthopyroxene + pyrite/pyrrhotite ± magnetite ± olivine ± talc ± magnesite), fO2 was set at ΔFMQ + 1 (30, 60 and 75 km), ΔFMQ (90 and 120 km), and ΔFMQ-1 (150 km). In order to test calculation sensitivity and improve the robustness, we calculated the results at ±1 fO2 unit for every case. Aqueous sulfur species are in equilibrium with pyrite or pyrrhotite based on fO2. Aqueous sulfur species considered here are H2S(g), H2S(aq), HS−, HSO3−, SO32−, HSO4−, SO42−, CaSO40, MgSO40, KSO4−, NaSO4−, S3−, SO2(g) and SO2(aq), and the corresponding thermodynamic data are reported in the DEW 2019 spreadsheet32.

Effect of sulfur isotope fractionation

Sulfur isotope fractionation of pyrite during hydrothermal processes was contoured on log fO2–pH diagrams based on the method of Ohmoto42. These calculations monitor sulfur isotope fractionation at prograde P–T stages at depths 30 km (200 °C, 1 GPa), 60 km (400 °C, 2 GPa), 75 km (550 °C, 2.5 GPa), 90 km (700 °C, 3 GPa) and 120 km (770 °C, 4 GPa). Reactions and equations of sulfur species include H2S(aq), HS−, HSO4−, and SO42−, and the relative isotopic fractionation (Δi = 34Si – 34SH2S) for sulfur species were calculated at higher temperatures according to the equation40:

where a, b, and c are empirically-determined constants, and T is temperature in Kelvin. The equilibrium constants for reactions and activity coefficients of aqueous species were recalculated for higher P–T conditions based on the DEW model31,32. The abundance of sulfur species and contours of sulfur isotope fractionation (compared to initial sulfur isotope of hydrothermal fluid at δ34S∑S = 0‰) as functions of fO2 and pH were calculated using Eqs. (17–25) listed in ref. 42.

The changes in isotope fractionation during pyrite crystallization from slab fluids (H2S dominated or SO42−-dominated) in closed system and open-system (Rayleigh fractionation) processes were modeled at the vein-formation temperature 550 °C. In a hydrothermal system, the isotope composition of an instantaneously separated solid phase i from a fluid is:

or

where δ34S0 is the initial fluid isotope composition (set as 0‰) and F is the fraction of sulfur remaining in the fluid.

Estimate of global sulfur input into subduction zones

The input sulfur flux FS and its isotope composition into subduction zones are:

where L is the global length of subduction zones, R is the convergence rate, t is the thickness of the sequence layers in the slab, ρ is the density of the sequence layers, CS is the sulfur concentration [S], and δ34St is the sulfur isotope composition of the sequence layers. The total effective length of subduction zones is ~38,500 km, which covers more than 90% of global trench length49. The convergence rate of 6.2 cm yr−1 used here is taken from an average rate of 17 active oceanic subduction zones36. Based on the oceanic lithosphere stratigraphy (Penrose style) and its average [S] and δ34S composition from the best current understanding (Supplementary Fig. 3), the calculated global sulfur input via subducting slabs is estimated to be 46.5 × 1012 g yr−1. The bulk slab sulfur isotope composition of this sulfur input is estimated at −3.60‰. Using the same method, the calculated global water flux (1.06 × 1015 g yr−1) of subducted slabs is very close to previous estimates (1.0 × 1015 g yr−1)49.

Sulfur output and net δ 34 S released by slab fluids

The output sulfur flux released from the subducted slab via fluids (fS) is:

and the net sulfur isotope composition of fluids released from the subducted slab (δ34Snet) is:

where CS-fluid refers to [S]fluid and ffluid to the fluid flux released from the subducting slab. Based on water flux (0.32 × 1015 gyr−1) and [S]fluid from the DEW model, the calculated sulfur output at 70–100 km is 2.46 × 1012 g yr−1 (5.3% of total input FS) with a δ34S value of −1.84 ± 3 ‰. The net δ34S value of slab fluids released at 70–100 km depths is further adjusted to −2.54 ± 3 ‰ (Fig. 9) considering fluid–rock isotopic exchange.

Our calculations indicate that along the subduction thermal gradient, at different subduction depths, the variations of temperature, pressure, fO2 and pH will not cause large sulfur isotope fractionation (Fig. 7). Thus, the fluid δ34S compositions obtained at 70–100 km depths can be extrapolated to different depths in the subduction zone. Following the similar assumptions and calculation approach, we obtained sulfur outfluxes and associated δ34S values of slab fluids released at 30–50 km (0.00004 × 1012 g yr−1, −1.0‰), 50–70 km (0.009 × 1012 g yr−1, −3.2‰), 100–150 km (0.32 × 1012 g yr−1, −0.1‰), and 150–230 km (0.11 × 1012 g yr−1, +1.0‰), based on the water flux released from the slab at different depths as calculated by van Keken et al.49. The total sulfur output at 30–230 km is calculated at 2.91 × 1012 g yr−1 (6.3% of total input FS) with a δ34S value of −2.13‰ (Fig. 9).

Uncertainties on output sulfur δ 34 S estimates

The estimates of sulfur fluxes released from the slab have significant uncertainties. However, our study provides a robust isotopic signature for the slab fluids. The δ34S estimate remains at slightly negative values in all of the following scenarios:

The uncertainty of δ34Snet is mostly dependent on the δ34S value of fluids released by the AOC at 70–100 km, which provides the major fluid flux and has a relatively high sulfur concentration (0.74 wt.%). Although we consider a large δ34S range of fluidAOC (−6 to +4‰), the errors on the δ34S of slab fluid released at 70–100 km are all less than ±2.5‰ (2σ). Changes in other parameters and assumptions cause variations of less than ±1‰ in δ34S. Hence, we estimate ±3‰ as a reasonable uncertainty.

Our study is based on the best current knowledge of slab structure and water budget49. However, new research based on ocean-bottom seismic data reports that mantle hydration may extend up to 24 km beneath the Moho54, which indicates that the subducting plate may contain much more water than previously thought49. If we adopt this assumption of a thicker serpentinized upper mantle54 and recalculate the water and sulfur fluxes (i.e., enlarged the serpentinite-dehydrated water amounts in the subduction zone accordingly), the sulfur input increases to 7.6 × 1013 g yr−1 and sulfur output increases to 3.93 × 1012 g yr−1 but the sulfur productivity (5.2%) of the subducting slab shows little variation. More importantly, the net δ34S displays almost no change at 70–100 km (−2.4‰). This consolidates our prediction of slab-released sulfur regarding the δ34S signatures of arc settings.

Subducted sediment types and their redox state may have a potential effect on our results, even though there currently is no firm consensus about how much sediment is subducted. Metasediment in the Franciscan complex contains red ferruginous chert, but its proportion is subordinate compared to greywackes77. Moreover, at the major sulfur release window (70–100 km), the sediment contribution to the total sulfur loss is small (less than 20%). The channelized fluids24,25 in subducted slabs (instead of pervasive fluids) prevent intensive sediment contamination of deeply-derived fluids. Here we conclude that the variable sediment protoliths and redox state will not influence our results significantly.

Code availability

The computer code including the Deep Earth Water model (2019) and EQ3 packages to perform the DEW calculations in this study is publicly available from the DEEP CARBON OBSERVATORY website [www.dewcommunity.org/resources.html] for research purposes.

References

Wallace, P. J. & Edmonds, M. The sulfur budget in magmas: evidence from melt Inclusions, submarine glasses, and volcanic gas emissions. Rev. Mineral. Geochem. 73, 215–246 (2011).

Evans, K. A. The redox budget of subduction zones. Earth Sci. Rev. 113, 11–32 (2012).

Farquhar, J., Bao, H. M. & Thiemens, M. Atmospheric influence of Earth’s earliest sulfur cycle. Science 289, 756–758 (2000).

Alt, J. C., Shanks, W. C. & Jackson, M. C. Cycling of sulfur in subduction zones: the geochemistry of sulfur in the Mariana-island arc and back-arc trough. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 119, 477–494 (1993).

de Hoog, J. C. M., Taylor, B. E. & van Bergen, M. J. Sulfur isotope systematics of basaltic lavas from Indonesia: implications for the sulfur cycle in subduction zones. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 189, 237–252 (2001).

de Hoog, J. C. M., Mason, P. R. D. & van Bergen, M. J. Sulfur and chalcophile elements in subduction zones: Constraints from a laser ablation ICP-MS study of melt inclusions from Galunggung Volcano, Indonesia. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 65, 3147–3164 (2001).

Metrich, N., Schiano, P., Clocchiatti, R. & Maury, R. C. Transfer of sulfur in subduction settings: an example from Batan Island (Luzon volcanic arc, Philippines). Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 167, 1–14 (1999).

Bénard, A. et al. Oxidising agents in sub-arc mantle melts link slab devolatilisation and arc magmas. Nat. Commun. 9, 3500 (2018).

Pons, M. L., Debret, B., Bouilhol, P., Delacour, A. & Williams, H. Zinc isotope evidence for sulfate-rich fluid transfer across subduction zones. Nat. Commun. 7, 13794 (2016).

Lee, C. T. A. et al. Sulfur isotopic compositions of deep arc cumulates. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 500, 76–85 (2018).

Jégo, S. & Dasgupta, R. Fluid-present melting of sulfide-bearing ocean-crust: experimental constraints on the transport of sulfur from subducting slab to mantle wedge. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 110, 106–134 (2013).

Tomkins, A. G. & Evans, K. A. Separate zones of sulfate and sulfide release from subducted mafic oceanic crust. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 428, 73–83 (2015).

Walters, J. B., Cruz‐Uribe, A. M. & Marschall, H. R. Isotopic compositions of sulfides in exhumed high‐pressure terranes: implications for sulfur cycling in subduction zones. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 20, 3347–3374 (2019).

Crossley, R. J., Evans, K. A., Jeon, H. & Kilburn, M. R. Insights into sulfur cycling at subduction zones from in-situ isotopic analysis of sulfides in high-pressure serpentinites and ‘hybrid’ samples from Alpine Corsica. Chem. Geol. 493, 359–378 (2018).

Evans, K. A., Tomkins, A. G., Cliff, J. & Fiorentini, M. L. Insights into subduction zone sulfur recycling from isotopic analysis of eclogite-hosted sulfides. Chem. Geol. 365, 1–19 (2014).

Su, W. et al. Sulfur isotope compositions of pyrite from high-pressure metamorphic rocks and related veins (SW Tianshan, China): Implications for the sulfur cycle in subduction zones. Lithos 348–349, 105212 (2019).

Li, J. L., Gao, J., Klemd, R., John, T. & Wang, X. S. Redox processes in subducting oceanic crust recorded by sulfide-bearing high-pressure rocks and veins (SW Tianshan, China). Contrib. Mineral. Petrol. 171, 72 (2016).

Brown, J. L., Christy, A. G., Ellis, D. J. & Arculus, R. J. Prograde Sulfide Metamorphism in Blueschist and Eclogite, New Caledonia. J. Petrol. 55, 643–670 (2014).

Canfield, D. E. The evolution of the Earth surface sulfur reservoir. Am. J. Sci. 304, 839–861 (2004).

Alt, J. C. et al. The role of serpentinites in cycling of carbon and sulfur: seafloor serpentinization and subduction metamorphism. Lithos 178, 40–54 (2013).

Alt, J. C. et al. Recycling of water, carbon, and sulfur during subduction of serpentinites: a stable isotope study of Cerro del Almirez, Spain. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 327, 50–60 (2012).

Alt, J. C. & Shanks, W. C. Microbial sulfate reduction and the sulfur budget for a complete section of altered oceanic basalts, IODP Hole 1256D (eastern Pacific). Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 310, 73–83 (2011).

Schwarzenbach, E. M. et al. Sulphur and carbon cycling in the subduction zone mélange. Sci. Rep. 8, 15517 (2018).

Taetz, S., John, T., Bröcker, M., Spandler, C. & Stracke, A. Fast intraslab fluid-flow events linked to pulses of high pore fluid pressure at the subducted plate interface. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 482, 33–43 (2018).

John, T. et al. Volcanic arcs fed by rapid pulsed fluid flow through subducting slabs. Nat. Geosci. 5, 489–492 (2012).

Bayet, L., John, T., Agard, P., Gao, J. & Li, J. L. Massive sediment accretion at ∼80 km depth along the subduction interface: Evidence from the southern Chinese Tianshan. Geology 46, 495–498 (2018).

Tan, Z. et al. Architecture and P-T-deformation-time evolution of the Chinese SW-Tianshan HP/UHP complex: implications for subduction dynamics. Earth-Sci. Rev. 197, 102894 (2019).

Shen, T. T. et al. UHP metamorphism documented in Ti-chondrodite- and Ti-clinohumite-bearing serpentinized ultramafic rocks from Chinese Southwestern Tianshan. J. Petrol. 56, 1425–1458 (2015).

Beinlich, A., Klemd, R., John, T. & Gao, J. Trace-element mobilization during Ca metasomatism along a major fluid conduit: Eclogitization of blueschist as a consequence of fluid-rock interaction. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 74, 1892–1922 (2010).

Schwarzenbach, E. M., Gill, B. C., Gazel, E. & Madrigal, P. Sulfur and carbon geochemistry of the Santa Elena peridotites: comparing oceanic and continental processes during peridotite alteration. Lithos 252–253, 92–108 (2016).

Sverjensky, D. A., Harrison, B. & Azzolini, D. Water in the deep Earth: the dielectric constant and the solubilities of quartz and corundum to 60 kb and 1200 degrees C. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 129, 125–145 (2014).

Huang, F. & Sverjensky, D. A. Extended Deep Earth Water Model for predicting major element mantle metasomatism. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 254, 192–230 (2019).

Foley, S. F. A reappraisal of redox melting in the Earth’s mantle as a function of tectonic setting and time. J. Petrol. 52, 1363–1391 (2011).

Tao, R. B. et al. Formation of abiotic hydrocarbon from reduction of carbonate in subduction zones: constraints from petrological observation and experimental simulation. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 239, 390–408 (2018).

Evans, K. A., Reddy, S. M., Tomkins, A. G., Crossley, R. J. & Frost, B. R. Effects of geodynamic setting on the redox state of fluids released by subducted mantle lithosphere. Lithos 278–281, 26–42 (2017).

Syracuse, E. M., van Keken, P. E. & Abers, G. A. The global range of subduction zone thermal models. Phys. Earth Planet. 183, 73–90 (2010).

Connolly, J. A. D. & Cesare, B. C-O-H-S fluid composition and oxygen fugacity in graphitic metapelites. J. Metamorph. Geol. 11, 379–388 (1993).

Tomkins, A. G. Windows of metamorphic sulfur liberation in the crust: Implications for gold deposit genesis. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 74, 3246–3259 (2010).

Evans, K. A. & Powell, R. The effect of subduction on the sulfur, carbon, and redox budget of lithospheric mantle. J. Metamorph. Geol. 33, 649–670 (2015).

Ohmoto, H. & Rye, R. O. in Geochemistry of Hydrothermal Ore Deposits (ed. Barnes, H. L.) 509–567 (Wiley, 1979).

Marini, L., Moretti, R. & Accornero, M. Sulfur isotopes in magmatic-hydrothermal systems, melts, and magmas. Rev. Mineral. Geochem. 73, 423–492 (2011).

Ohmoto, H. Systematics of sulfur and carbon isotopes in hydrothermal ore deposits. Econ. Geol. 67, 551–578 (1972).

Galvez, M. E., Connolly, J. A. D. & Manning, C. E. Implications for metal and volatile cycles from the pH of subduction zone fluids. Nature 539, 420–424 (2016).

Farquhar, J., Wu, N. P., Canfield, D. E. & Oduro, H. Connections between sulfur cycle evolution, sulfur isotopes, sediments, and base metal sulfide deposits. Econ. Geol. 105, 509–533 (2010).

Labidi, J., Cartigny, P., Birck, J. L., Assayag, N. & Bourrand, J. J. Determination of multiple sulfur isotopes in glasses: a reappraisal of the MORB δ34S. Chem. Geol. 334, 189–198 (2012).

Alt, J. C. Sulfur isotopic profile through the oceanic crust: sulfur mobility and seawater-crustal sulfur exchange during hydrothermal alteration. Geology 23, 585–588 (1995).

Alt, J. C. et al. Uptake of carbon and sulfur during seafloor serpentinization and the effects of subduction metamorphism in Ligurian peridotites. Chem. Geol. 322, 268–277 (2012).

Schwarzenbach, E. M. Serpentinization, Fluids and Life: Comparing Carbon and Sulfur Cycles in Modern and Ancient Environments. Thesis, ETH Zurich (2011).

van Keken, P. E., Hacker, B. R., Syracuse, E. M. & Abers, G. A. Subduction factory: 4. Depth-dependent flux of H2O from subducting slabs worldwide. J. Geophys. Res. 116, B01401 (2011).

Hilton, D. R., Fischer, T. P. & Marty, B. Noble gases and volatile recycling at subduction zones. Rev. Miner. 47, 319–370 (2002).

Wallace, P. J. Volatiles in subduction zone magmas: concentrations and fluxes based on melt inclusion and volcanic gas data. J. Volcanol. Geoth. Res. 140, 217–240 (2005).

Bebout, G. E. Metamorphic chemical geodynamics of subduction zones. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 260, 373–393 (2007).

Peacock, S. M. Fluid processes in subduction zones. Science 248, 329–337 (1990).

Cai, C., Wiens, D. A., Shen, W. & Eimer, M. Water input into the Mariana subduction zone estimated from ocean-bottom seismic data. Nature 563, 389–392 (2018).

Ague, J. J. & Nicolescu, S. Carbon dioxide released from subduction zones by fluid-mediated reactions. Nat. Geosci. 7, 355–360 (2014).

Chaussidon, M., Albarede, F. & Sheppard, S. M. F. Sulphur isotope variations in the mantle from ion microprobe analyses of micro-sulphide inclusions. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 92, 144–156 (1989).

Kelley, K. A. & Cottrell, E. Water and the oxidation state of subduction zone magmas. Science 325, 605–607 (2009).

Evans, K. A., Elburg, M. A. & Kamenetsky, V. S. Oxidation state of subarc mantle. Geology 40, 783–786 (2012).

Foden, J., Sossi, P. A. & Nebel, O. Controls on the iron isotopic composition of global arc magmas. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 494, 190–201 (2018).

Benard, A., Woodland, A. B., Arculus, R. J., Nebel, O. & McAlpine, S. R. B. Variation in sub-arc mantle oxygen fugacity during partial melting recorded in refractory peridotite xenoliths from the West Bismarck Arc. Chem. Geol. 486, 16–30 (2018).

Chin, E. J., Shimizu, K., Bybee, G. M. & Erdman, M. E. On the development of the calc-alkaline and tholeiitic magma series: A deep crustal cumulate perspective. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 482, 277–287 (2018).

Kilgore, M. L., Peslier, A. H., Brandon, A. D. & Lamb, W. M. Water and oxygen fugacity in the lithospheric mantle wedge beneath the Northern Canadian Cordillera (Alligator Lake). Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 19, 3844–3869 (2018).

Tollan, P. & Hermann, J. Arc magmas oxidized by water dissociation and hydrogen incorporation in orthopyroxene. Nat. Geosci. 12, 667–671 (2019).

Malaspina, N., Scambelluri, M., Poli, S., Van Roermund, H. L. M. & Langenhorst, F. The oxidation state of mantle wedge majoritic garnet websterites metasomatised by C-bearing subduction fluids. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 298, 417–426 (2010).

Song, S. G., Su, L., Niu, Y., Lai, Y. & Zhang, L. CH4 inclusions in orogenic harzburgite: evidence for reduced slab fluids and implication for redox melting in mantle wedge. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 73, 1737–1754 (2009).

Fiege, A. et al. Experimental investigation of the S and S-isotope distribution between H2O S ± Cl fluids and basaltic melts during decompression. Chem. Geol. 393–394, 36–54 (2015).

Fiege, A. et al. Sulfur isotope fractionation between fluid and andesitic melt: an experimental study. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 142, 501–521 (2014).

Hutchison, W. et al. Sulphur isotopes of alkaline magmas unlock long-term records of crustal recycling on Earth. Nat. Commun. 10, 4208 (2019).

Liebmann, J. et al. Tracking water-rock interaction at the Atlantis Massif (MAR, 30 degrees N) using sulfur geochemistry. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 19, 4561–4583 (2018).

Whitehouse, M. J. Multiple sulfur isotope determination by SIMS: evaluation of reference sulfides for Δ33S with observations and a case study on the determination of Δ36S. Geostand. Geoanal. Res. 37, 19–33 (2013).

Chen, L. et al. Extreme variation of sulfur isotopic compositions in pyrite from the Qiuling sediment-hosted gold deposit, West Qinling orogen, central China: an in situ SIMS study with implications for the source of sulfur. Miner. Depos. 50, 643–656 (2015).

Ding, T. et al. Calibrated sulfur isotope abundance ratios of three IAEA sulfur isotope reference materials and V-CDT with a reassessment of the atomic weight of sulfur. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 65, 2433–2437 (2001).

Wolery, T. J. EQ3NR, a computer program for geochemical aqueous speciation-solubility calculations: theoretical manual, user’s guide, and related documentation (Version 7.0); Part 3 (DOE, 1992).

Sverjensky, D. A. Thermodynamic modelling of fluids from surficial to mantle conditions. J. Geol. Soc. 176, 348–374 (2019).

Sverjensky, D. A. & Huang, F. Diamond formation due to a pH drop during fluid-rock interactions. Nat. Commun. 6, 8702 (2015).

Debret, B. et al. Evolution of Fe redox state in serpentine during subduction. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 400, 206–218 (2014).

Wakabayashi, J. Anatomy of a subduction complex: architecture of the Franciscan Complex, California, at multiple length and time scales. Int. Geol. Rev. 57, 669–746 (2015).

Kagoshima, T. et al. Sulphur geodynamic cycle. Sci. Rep. 5, 8330 (2015).

Acknowledgements

This project was supported by the National Key R&D Program of China (2018YFA0702701), National Natural Science Foundation of China (41772056 and 41390445). J.L.L. thanks the funding from Youth Innovation Promotion Association CAS (2018090) and the CSC for supporting his one-year stay at Yale University and three months at Freie Univeristät Berlin. J.J.A. gratefully acknowledges support from the U.S. National Science Foundation (EAR–1650329). NordSIMS is a Swedish infrastructure supported under VR grant 2017-00671; this is contribution 610. We thank U. Wiechert and F. Schmid for help with bulk-rock S analyses; Q. Mao and D. Zhang for help with EMP analyses; and H. Jeon, L. Chen, L.L. Dong, and J. Li for help with SIMS analyses. We are grateful to J.A.D. Connolly, S. Tassara, B.T. Li, and X.Q. Zhou for their helpful discussions and suggestions. Special thanks go to P. van Keken for providing detailed global water flux data, which enhances the reliability of our mass-balance calculation significantly.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.L.L. and T.J. designed the study. J.L.L., T.J., J.G. and R.K. collected the samples. J.L.L., R.K. and X.S.W. performed the microprobe mapping and laser trace-element analysis. E.M.S. and J.L.L. conducted the bulk sulfur isotope analysis. J.L.L. and M.J.W. conducted the SIMS analysis. F.H. performed the DEW calculation. J.L.L., E.M.S., T.J. and J.J.A. performed the mass-balance calculations. All authors contributed to the extensive discussion and manuscript writing.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Peer review information Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, JL., Schwarzenbach, E.M., John, T. et al. Uncovering and quantifying the subduction zone sulfur cycle from the slab perspective. Nat Commun 11, 514 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-14110-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-14110-4

This article is cited by

-

Sulfide saturation and resorption modulates sulfur and metal availability during the 2014–15 Holuhraun eruption, Iceland

Communications Earth & Environment (2024)

-

Lower crustal assimilation revealed by sulfur isotope systematics of the Bear Valley Intrusive Suite, southern Sierra Nevada Batholith, California, USA

Contributions to Mineralogy and Petrology (2024)

-

Mantle wedge oxidation from deserpentinization modulated by sediment-derived fluids

Nature Geoscience (2023)

-

Sulfide minerals and chalcophile elements in The Pleiades Volcanic Field, Antarctica: implications for the distribution of chalcophile metals in continental intraplate alkaline magma systems

Contributions to Mineralogy and Petrology (2023)

-

Slab-derived devolatilization fluids oxidized by subducted metasedimentary rocks

Nature Geoscience (2022)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.