Abstract

Transition metal catalyzed Sonogashira cross-coupling of terminal alkynes with aryl(vinyl) (pseudo)halides has been successfully extended to alkyl halides for the synthesis of functionalized internal alkynes. The direct alkynylation of remote unfunctionalized sp3 carbon by terminal alkynes remains difficult to realize. We report herein an approach to this synthetic challenge by developing two catalytic remote sp3 carbon alkynylation protocols. In the presence of a catalytic amount of Cu(I) salt and a tridentate ligand (tBu3-terpyridine), O-acyloximes derived from cycloalkanones and acyclic ketones are efficiently coupled with terminal alkynes to afford a variety of γ- and δ-alkynyl nitriles and γ-alkynyl ketones, respectively. These reactions proceed through a domino sequence involving copper-catalyzed reductive generation of iminyl radical followed by radical translocation via either β-scission or 1,5-hydrogen atom transfer (1,5-HAT) and copper-catalyzed alkynylation of the resulting translocated carbon radicals. The protocols are applicable to complex natural products.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Alkyne is an important functional group in organic synthesis and is also found in natural products and pharmaceuticals1. Among many available synthetic methodologies, the Sonogashira reaction is one of the most reliable transformations for the synthesis of internal alkynes2. Initially developed for coupling of terminal alkynes with aryl/vinyl (pseudo)halides in the presence of Pd/Cu3 or Cu catalyst alone4,5, the reaction has subsequently been extended to alkyl bromides/iodides (Fig. 1a) using Pd/Cu6, Ni/Cu7, and Cu/hν8 catalytic systems9. In a different approach, in situ oxidation of N,N-dimethylaniline derivatives to the corresponding iminiums followed by nucleophilic addition of copper acetylides has been developed for the synthesis of propargylamines (Fig. 1b)10. The direct alkynylation of remote unfunctionalized sp3 carbon by terminal alkynes remains, to the best of our knowledge, unknown.

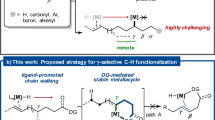

a Sonogashira coupling of unactivated alkyl halides with terminal alkynes (Fu3); b Cu-catalyzed alkynylation of C(sp3)-H adjacent to a nitrogen atom (Li7); c terminal alkynes as radical acceptors (Chen and Xiao19, Leonori28); d alkynylation of C-radicals with Waser’s EBX reagent25; e reaction design: working hypothesis; f Cu-catalyzed C(sp3)–C(sp) coupling of oxime esters with terminal alkynes. NHC N-heterocyclic carbene, dtbbp 4,4′-di-tert-butyl-2,2′-dipyridyl.

Using nitrogen-centered radicals (NCRs) as precursors of carbon-centered radicals has become the focus of recent intense research efforts11,12,13,14. In this context, redox-active acyclic15 and cyclic16 oxime derivatives, pioneered by Forrester and Zard, respectively, have been demonstrated to be versatile precursors of iminyl radicals under either oxidative or reductive conditions. Depending on the structure of oximes, the iminyl radicals can evolve to a carbon radical through either β-scission17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32 or 1,5-hydrogen atom transfer (1,5-HAT) process33,34,35,36,37,38,39. The resulting carbon radicals can then be trapped by radical acceptors, affording remote C(sp3) functionalized alkylnitriles and ketones. However, in spite of a great amount of dedicated efforts, synthetic transformations involving translocated carbon radicals were limited mainly to the radical addition/homolytic substitution (SH2) and oxidation reactions. For example, terminal alkynes have been used as radical acceptors by Chen and Xiao for the synthesis of functionalized dihydronaphthalenes (Fig. 1c)22. Recent report from Leonori’s group showed that even in the presence of a Ni catalyst, radical addition to terminal alkyne occurred at the expense of the cross-coupling reaction to afford 1,2-disubstituted alkenes (Fig. 1c)31. To avoid this radical addition problem, Chen has very recently devised a clever three-component process, in which the primary radical resulting from the β-scission was trapped by styrene to generate a more stable benzylic radical, which can then undergo the Cu-catalyzed cross-coupling with terminal alkynes32. To the best of our knowledge, only the Waser’s hypovalent EBX reagent was capable of trapping the primary alkyl radical to afford the γ-alkynyl nitriles (Fig. 1d)28,40,41.

Stimulated by the challenges associated with the direct alkynylation of unfunctionalized remote sp3 carbon, we became interested in alkynylation of oxime esters with terminal alkynes. The underline principle is outlined in Fig. 1e. Reduction of O-acyloximes 1 (cyclic) or 2 (acyclic) by copper acetylide A, formed in situ from terminal alkyne 3 and Cu(I) species, would afford Cu(II) intermediate B and iminyl radical C. β-Scission or 1,5-HAT of the latter would generate the carbon-centered radical D which, upon radical oxidative addition to B, would afford Cu(III) species E. Facile reductive elimination from E would furnish the alkynylated product with concurrent regeneration of the Cu(I) catalytic species. In this catalytic cycle, copper went through three oxidation states and the high-valent Cu(III) species, difficult to access by classic oxidative addition, would be formed via a SET process. Although most of radical–Cu(II) rebound processes involved activated secondary or tertiary benzylic carbons42,43,44, we have very recently shown that it is also possible to functionalize the primary radical in the presence of copper under photocatalysis conditions45,46. While dual photocatalyst/Cu catalytic system has emerged as a powerful tool for cross-coupling reactions47, the catalytic cycle depicted in Fig. 1e using copper as the only catalyst remained uncommon48,49,50,51. We report herein the successful realization of this endeavor by developing synthesis of γ- and δ-alkynyl nitriles 4 and γ-alkynyl ketones 5 from simple oxime esters 1 or 2 and terminal alkynes 3 (Fig. 1f).

Results

Cu-catalyzed alkynylation of cycloalkanone oxime esters

We began our studies by investigating the reductive alkynylation of cyclobutanone oxime esters with phenylacetylene (3a). After systematic survey of the ester groups, the copper sources, the ligands, the bases, the temperature, and the solvents with or without Blue LEDs irradiation (Supplementary Methods, Tables 1–7), the optimum conditions found consisted of performing the reaction of 1a with 3a in acetonitrile (c 0.2 M) in the presence of CuI (0.1 equiv), 4,4,’4”-tri-tert-butyl-2,2′:6′,2″-terpyridine (tBu3-TERPY, 0.2 equiv) and potassium carbonate (2.0 equiv) at 60 °C. Under these conditions, 4a was isolated in 76% yield. We stress that the use of tBu3-TERPY as a ligand is determinant to the success of the reaction.

As shown in Fig. 2, a range of aryl acetylenes bearing electron-donating and electron-withdrawing groups at different positions underwent the C(sp3)–C(sp) coupling with O-acyloxime 1a to afford the γ-alkynyl alkylnitriles in good to high yields (4a–4j). Alkynes attached to an heteroarene such as pyridine, indole, and even thiophene were compatible to afford alkynylated nitriles 4k–4m in satisfactory yields. (S)-Methyl 4-ethynyl-N-Boc-phenylalanate took part in the reaction to give 4n in 60% yield. Aliphatic alkynes participated in the reaction to deliver the products 4o–4u in good yields. A range of functional groups, such as ester, amide, carbamate, sulfonamide bearing an acidic proton, were well tolerated. However, reaction of unprotected 4-ethynylaniline and 3-ethynylphenol with 1a afforded the desired product in low yields (<30%). Performing the reaction of 1a with 3q at 2.0 mmol scale under standard conditions provided 4q in similar isolated yield (70%).

The alkynylation protocol was next applied to a diverse set of oxime esters (Fig. 3). Oxime esters derived from C-3 mono- and disubstituted cyclobutanones underwent alkynylation smoothly to afford the corresponding γ-alkynylated nitriles (4v–4af). Nonsymmetrical C-2 substituted cyclobutanone derivatives underwent β-scission at the more substituted position to deliver the alkynylation products (4ag–4ai) in good yields. Ring-opening alkynylation of oxetan-3-one oxime ester proceeded well to provide the coupling product 4af in 62% yield. 2,3,3-Trisubstituted oxime ester was alkynylated without event to afford the highly functionalized alkyne 4aj. Bicyclo[3.2.0]hept-2-en-6-one-derived oxime ester was converted to trans-3,4-disubstituted cyclopentene derivative 4ak in 76% yield. Gratefully, oxime esters derived from less strained cyclopentanones and dihydrofuran-3(2H)-one underwent similar transformation to afford δ-alkynylated nitriles (4al, 4am, 4an) in good yields. It is nevertheless important to note that the presence of a substituent alpha to the oxime function is needed to drive the fragmentation and that the oxime esters derived from cyclohexanone failed to produce the ω-alkynylated alkylnitriles. We stress that aryl chloride (4ad, 4ae) and alkenes (4ah, 4ak), including α,β-unsaturated ester (4w), which are excellent radical acceptors of the transient nucleophilic alkyl radicals, remained unaltered.

Cu-catalyzed γ-C(sp3)-H alkynylation of linear oxime esters

Oxime esters derived from linear ketones were next examined for the synthesis of γ-alkynylated ketones by a domino sequence involving reductive generation of iminyl radicals followed by 1,5-HAT and alkynylation of the resulting carbon-centered radicals52,53,54,55,56. Reaction of 2a (R1 = R2 = Ph) with 3a (R = Ph) under aforementioned standard conditions afforded only a trace amount of 5a, with the unfunctionalized ketone being isolated as the major product. This result was not unexpected considering the reversibility of 1,5-HAT of iminyl radicals to benzylic radicals35. After an exhaustive optimization of reaction conditions (see Supplementary Methods, Tables 8–14), we found that stirring a DCE solution of 2a (0.1 mmol) with 3a (0.2 mmol) at 45 °C in the presence of (CuOTf)2·C6H6 (0.05 equiv), tBu3-TERPY (0.1 equiv), and K2CO3 (2 equiv) provided the desired internal alkyne 5a in 76%. The generality of this protocol is shown in Fig. 4. Regardless of the electronic nature of the oxime esters and the acetylenes, the γ-C(sp3)-H alkynylation proceeded smoothly to afford the corresponding γ-alkynylated ketones (5a–5p) in good yields. Oxime esters derived from aliphatic ketones (5q–5t) were selectively alkynylated at the benzylic position. Functional groups such as terminal alkyne (5t), nitrile (5s), thioether (5ae), enyne (5ag), alkyl chloride (5ac), and heteroarenes (5u–5w) were well tolerated. Alkynylation on a tertiary carbon was also feasible (5af), albeit with reduced yield. An experiment performed at 1.0 mmol scale between O-acyloxime 2b and phenylacetylene (3a) gave 5b in 76% isolated yield. However, the presence of an aryl (R2 = Aryl group) or a heteroatom substituent (R2 = SMe, 5ae) in oxime 2 is needed in order for the domino alkynylation process to occur. In fact, the bond dissociation energy (BDE) of iminyl NH bonds (93 kcal/mol) is lower than most of the C(sp3)-H bond (96-105 kcal/mol), which makes the 1,5-HAT of iminyl radical to carbon radical thermodynamically unfavorable. One solution to this problem is to perform the reaction under acidic conditions15,33,39, which are unfortunately incompatible with the present alkynylation conditions.

Application of these protocols to the late-stage functionalization of natural product-derived alkynes was examined. As shown in Fig. 5a, estrone-derived alkyne 6a, γ-tocopherol-derived alkyne 7a and glucose derivative 8a were successfully engaged in the reaction with cyclic oxime ester 1a to produce the internal alkynes 6b, 7b, and 8b, respectively, in synthetically useful yields. Reaction of mestranol derivative 9a with oxime ester 2b afforded the expected γ-alkynylated ketone 9b in 72% yield. Finally, post-functionalization of γ-alkynylated alkylnitriles and ketones were performed to demonstrate the synthetic potential of these building blocks. Thus, Ni/BPh3-catalyzed [2 + 2 + 2] cycloaddition of nitrile 4c with dec-5-yne (10) afforded the fused pyridines 11 and 12 in 50 and 40% yields, respectively57. On the other hand, base-promoted cyclization of the alkynyl ketone 5a afforded the trisubstituted 4H-pyran 13 in 85% yield (Fig. 5b)58.

Control experiments were conducted to gain insights on the possible reaction mechanism. Addition of radical inhibitors such as TEMPO or TBHP to the reaction mixture suppressed or substantially reduced the product formation (Supplementary Methods, S283). The reaction of 2o with phenylacetylene 3a afforded enyne 5ah in 75% yield, while reaction of 1t with 3t provided indane 14 (57%, d.r. 1:1) involving a 5-exo-trig radical cyclization before the final Cu-catalyzed cross-coupling reaction (Fig. 6). The results of these control experiments indicated clearly the existence of the radical intermediates and the feasibility of the reaction pathway depicted in Fig. 1e.

[a] 2o (0.1 mmol), 3a (0.2 mmol, 2.0 equiv), (CuOTf)2·C6H6 (0.05 equiv), tBu3-TERPY (0.1 equiv), K2CO3 (2.0 equiv), DCE (2.0 mL, c 0.05 M), 45 °C, under nitrogen atmosphere. [b] 1t (0.2 mmol), 3t (0.4 mmol), CuI (0.1 equiv), tBu3-TERPY (0.2 equiv), K2CO3 (2.0 equiv), CH3CN (1.0 mL, c 0.2 M), 60 °C, under nitrogen atmosphere.

Discussion

Generation of heteroatom-centered radicals followed by β-scission or 1,5-HAT and functionalization of the resulting translocated carbon radicals have been an active research area for the past few years. However, the reported transformations involved mainly the addition of the C-radicals to multiple bonds including alkynes, atom transfer, and reduction/oxidation reaction. To address this limitation, we proposed to combine this radical chemistry with the powerful transition metal-catalyzed cross-coupling reaction, and demonstrated that capture of the C radical by organocopper salts followed by reductive elimination of the resulting Cu(III) intermediate is a highly efficient way to functionalize the translocated C radical. Indeed, we developed efficient and functional group-tolerant Cu-catalyzed syntheses of γ- and δ-alkynyl nitriles and γ-alkynyl ketones, respectively, from readily accessible O-acyloximes and terminal alkynes. The reaction proceeded through a domino sequence involving reductive generation of iminyl radical followed by its translocation to a carbon-centered radical via either β-scission or 1,5-HAT and copper-catalyzed coupling of the resulting C(sp3) radical with the terminal alkynes. The catalytic amount of copper played a triple roles: it reacted with terminal alkyne to form the copper (I) acetylide, which in turn served as a reductant to reduce the oxime ester to generate the iminyl radical and the Cu(II) species. Finally, Cu(II) intermediate underwent radical rebound with the translocated carbon radical to produce the Cu(III) species. Reductive elimination of the latter afforded the remote alkynylated alkylnitriles or ketones with the concurrent regeneration of the Cu(I) species.

Methods

Cu-catalyzed alkynylation of cycloalkanone oxime esters

O-acyloximes 1 (0.2 mmol), terminal alkynes 3 (0.4 mmol, 2.0 equiv), K2CO3 (0.4 mmol, 2.0 equiv), CuI (0.02 mmol, 0.1 equiv), and tBu3-TERPY (0.04 mmol, 0.2 equiv) were placed in a dry Schlenk tube. The reaction vessel was evacuated and filled up with nitrogen three times, then CH3CN (1.0 mL) was added at rt. After being stirred at 60 °C for 12 h, the reaction mixture was diluted with water and extracted with DCM. The combined organic layers were washed with aqueous NH4Cl solution and dried over anhydrous MgSO4. After removal of the solvent under reduced pressure, the crude product was purified by column chromatography (silica gel, eluent: ether/petroleum ether) to give the corresponding γ- or δ-alkynyl nitrile 4.

Cu-catalyzed γ-C(sp3)-H alkynylation of linear oxime esters

A suspension of O-acyloximes 2 (0.1 mmol), K2CO3 (0.2 mmol, 2.0 equiv), tBu3-TERPY (0.01 mol, 0.1 equiv), and (CuOTf)2·C6H6 (0.005 mmol, 0.05 equiv) in DCE (c 0.05 M) was deoxygenated by freeze–pump–thaw cycles. Alkyne 3 (0.2 mmol, 2.0 equiv) was introduced and the reaction mixture was stirred at 45 °C until the complete consumption of the starting materials (monitored by TLC). The reaction mixture was poured into a saturated NaHCO3 solution and extracted with EtOAc. The combined organic layers were washed with aqueous NH4Cl solution, dried over Na2SO4, and evaporated to dryness under reduced pressure. The residue was purified by flash column chromatography on silica gel to afford the corresponding γ-alkynylated ketone 5.

Data availability

The authors declare that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper and the Supplementary Information, as well as from the authors upon request.

References

Galm, U. et al. Antitumor antibiotics: bleomycin, enediynes, and mitomycin. Chem. Rev. 105, 739 (2005).

Sonogashira, K. Cross-coupling reactions to sp carbon atoms. in Metal-Catalyzed Cross-coupling Reactions (eds Diederich, F. & Stang, P. J.) 203–229 (Wiley-VCH, Weinheim, 1998).

Sonogashira, K., Tohda, Y. & Hagihara, N. A convenient synthesis of acetylenes: catalytic substitutions of acetylenic hydrogen with bromoalkenes, iodoarenes, and bromopyridines. Tetrahedron Lett. 16, 4467 (1975).

Okuro, K., Furuune, M., Enna, M., Miura, M. & Nomura, M. Synthesis of aryl- and vinylacetylene derivatives by copper-catalyzed reaction of aryl and vinyl iodides with terminal alkynes. J. Org. Chem. 58, 4716 (1993).

Monnier, F., Turtaut, F., Duroure, L. & Taillefer, M. Copper-catalyzed Sonogashira-type reactions under mild palladium-free conditions. Org. Lett. 10, 3203 (2008).

Eckhardt, M. & Fu, G. C. The first applications of carbene ligands in cross-couplings of alkyl electrophiles: Sonogashira reactions of unactivated alkyl bromides and iodides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 125, 13642 (2003).

Vechorkin, O., Barmaz, D., Proust, V. & Hu, X. Ni-Catalyzed Sonogashira coupling of nonactivated alkyl halides: orthogonal functionalization of alkyl iodides, bromides, and chlorides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 131, 12078 (2009).

Hazra, A., Lee, M. T., Chiu, J. F. & Lalic, G. Photoinduced copper-catalyzed coupling of terminal alkynes and alkyl iodides. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 57, 5492 (2018).

Liu, W., Li, L. & Li, C.-J. Empowering a transition-metal-free coupling between alkyne and alkyl iodide with light in water. Nat. Commun. 6, 6526 (2015).

Li, Z. & Li, C.-J. CuBr-Catalyzed efficient alkynylation of sp3 C-H bonds adjacent to a nitrogen atom. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 126, 11810 (2004).

Zard, S. Z. Recent progress in the generation and use of nitrogen-centred radicals. Chem. Soc. Rev. 37, 1603 (2008).

Chen, J.-R., Hu, X.-Q., Lu, L.-Q. & Xiao, W.-J. Visible light photoredox-controlled reactions of N-radicals and radical ions. Chem. Soc. Rev. 45, 2044 (2016).

Davies, J., Morcillo, S. P., Douglas, J. J. & Leonori, D. Hydroxylamine derivatives as nitrogen-radical precursors in visible-light photochemistry. Chem. Eur. J. 24, 12154 (2018).

Stateman, L. M., Nakafuku, K. M. & Nagib, D. A. Remote C-H functionalization via selective hydrogen atom transfer. Synthesis 50, 1569 (2018).

Forrester, A. R., Napier, R. J. & Thomson, R. H. Iminyls. Part 7. Intramolecular hydrogen abstraction; synthesis of heterocyclic analogues of α-tetralone. J. Chem. Soc. Perkin Trans. 1, 984 (1981).

Boivin, J., Fouquet, E. & Zard, S. Z. Iminyl radicals: part II. ring opening of cyclobutyl- and cyclopentyliminyl radicals. Tetrahedron 50, 1757 (1994).

Nishimura, T., Yoshinaka, T., Nishiguchi, Y., Maeda, Y. & Uemura, S. Iridium-catalyzed ring cleavage reaction of cyclobutanone O-benzoyloximes providing nitriles. Org. Lett. 7, 2425 (2005).

Li, L., Chen, H., Mei, M. & Zhou, L. Visible-light promoted γ-cyanoalkyl radical generation: three-component cyanopropylation/etherification of unactivated alkenes. Chem. Commun. 53, 11544 (2017).

Yang, H.-B. & Selander, N. Divergent iron-catalyzed coupling of O-acyloximes with silyl enol ethers. Chem. Eur. J. 23, 1779 (2017).

Gu, Y.-R., Duan, X.-H., Yang, L. & Guo, L.-N. Direct C−H cyanoalkylation of heteroaromatic N-oxides and quinones via C−C bond cleavage of cyclobutanone oximes. Org. Lett. 19, 5908 (2017).

Zhao, B. & Shi, Z. Copper-catalyzed intermolecular Heck-like coupling of cyclobutanone oximes initiated by selective C-C bond cleavage. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 56, 12727 (2017).

Yu, X.-Y. et al. A visible-light-driven iminyl radical-mediated C-C single bond cleavage/radical addition cascade of oxime esters. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 57, 738 (2018).

Yu, X.-Y., Zhao, Q.-Q., Chen, J., Chen, J.-R. & Xiao, W.-J. Copper-catalyzed radical cross-coupling of redox-active oxime esters, styrenes, and boronic acids. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 57, 15505 (2018).

Wu, J., Zhang, J.-Y., Gao, P., Xu, S.-L. & Guo, L.-N. Copper-catalyzed redox-neutral cyanoalkylarylation of activated alkenes with cyclobutanone oxime esters. J. Org. Chem. 83, 1046 (2018).

Zhao, J.-F., Gao, P., Duan, X.-H. & Guo, L.-N. Iron-catalyzed ring-opening/allylation of cyclobutanone oxime esters with allylic sulfones. Adv. Synth. Catal. 360, 1775 (2018).

Zhao, B. et al. Photoinduced fragmentation-rearrangement sequence of cycloketoxime esters. Org. Chem. Front 5, 2719 (2018).

Shen, X., Zhao, J.-J. & Yu, S. Photoredox-catalyzed intermolecular remote C−H and C−C vinylation via iminyl radicals. Org. Lett. 20, 5523 (2018).

Le Vaillant, F. et al. Fine-tuned organic photoredox catalysts for fragmentation-alkynylation cascades of cyclic oxime ethers. Chem. Sci. 9, 5883 (2018).

Ding, D., Lan, Y. L., Lin, Z. & Wang, C. Synthesis of gem-difluoroalkenes by merging Ni-catalyzed C-F and C-C bond activation in cross-electrophile coupling. Org. Lett. 21, 2723 (2019).

He, Y., Anand, D., Sun, Z. & Zhou, L. Visible-light-promoted redox neutral γ,γ-difluoroallylation of cycloketone oxime ethers with trifluoromethyl alkenes via C−C and C−F bond cleavage. Org. Lett. 21, 3769 (2019).

Dauncey, E. M., Dighe, S. U., Douglas, J. J. & Leonori, D. A dual photoredox-nickel strategy for remote functionalization via iminyl radicals: radical ring opening-arylation, -vinylation and -alkylation cascades. Chem. Sci. 10, 7728 (2019).

Chen., J. et al. Photoinduced, copper-catalyzed radical cross-coupling of cycloketone oxime esters, alkenes, and terminal alkynes. Org. Lett. 21, 4359 (2019).

Shu, W. & Nevado, C. Visible-light-mediated remote aliphatic C-H functionalizations through a 1,5-hydrogen transfer cascade. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 56, 1881 (2017).

Li, Y., Mao, R. & Wu, J. N-Radical initiated aminosulfonylation of unactivated C(sp3)-H bond through insertion of sulfur dioxide. Org. Lett. 19, 4472 (2017).

Dauncey, E. M., Morcillo, S. P., Douglas, J. J., Sheikh, N. S. & Leonori, D. Photoinduced remote functionalisations by iminyl radical promoted C-C and C-H bond cleavage cascades. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 57, 744 (2018).

Jiang, H. & Studer, A. α-Aminoxy-acid-auxiliary-enabled intermolecular radical γ-C(sp3)-H functionalization of ketones. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 57, 1692 (2018).

Ma, Z. ‐Y., Guo, L. ‐N., Gu, Y. ‐R., Chen, L. & Duan, X. ‐H. Iminyl radical-mediated controlled hydroxyalkylation of remote C(sp3)-H bond via tandem 1,5-HAT and difunctionalization of aryl alkenes. Adv. Synth. Catal. 360, 4341 (2018).

Chen, L. et al. Iminyl radical-triggered 1,5-hydrogen-atom transfer/Heck-type coupling by visible-light photoredox catalysis. J. Org. Chem. 84, 6475 (2019).

Torres-Ochoa, R. O., Leclair, A., Wang, Q. & Zhu, J. Iron-catalysed remote C(sp3)-H azidation of O-acyl oximes and N-acyloxy imidates enabled by 1,5-hydrogen atom transfer of iminyl and imidate radicals: synthesis of γ-azido ketones and β-azido alcohols. Chem. Eur. J. 25, 9477 (2019).

Morcillo, S. P. et al. Photoinduced remote functionalization of amides and amines using electrophilic nitrogen radicals. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 57, 12945 (2018).

Wang, L., Xia, Y., Bergander, K. & Studer, A. Site-specific radical alkynylation of unactivated C−H bonds. Org. Lett. 20, 5817 (2018).

Zhang, W. et al. Enantioselective cyanation of benzylic C–H bonds via copper-catalyzed radical relay. Science 353, 1014 (2016).

Wang, F., Chen, P. & Liu, G. Copper-catalyzed radical relay for asymmetric radical transformations. Acc. Chem. Res. 51, 2036 (2018).

Fu, L., Zhou, S., Wan, X., Chen, P. & Liu, G. Enantioselective trifluoromethylalkynylation of alkenes via copper-catalyzed radical relay. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140, 10965 (2018).

Bao, X., Wang, Q. & Zhu, J. Dual photoredox/copper catalysis for the remote C(sp3)-H functionalization of alcohols and alkyl halides by N-alkoxypyridinium salts. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 58, 2139 (2019).

Bao, X., Wang, Q. & Zhu, J. Remote C(sp3)-H arylation and vinylation of N-alkoxypyridinium salts to δ-aryl and δ-vinyl alcohols. Chem. Eur. J. 25, 11630 (2019).

Hossain, A., Bhattacharyya, A. & Reiser, O. Copper’s rapid ascent in visible-light photoredox catalysis. Science 364, 450 (2019).

Li, Z., Wang, Q. & Zhu, J. Copper-catalyzed arylation of remote C(sp3)-H bonds in carboxamides and sulfonamides. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 57, 13288 (2018).

Bao, X., Wang, Q. & Zhu, J. Copper-catalyzed remote C(sp3)-H azidation and oxidative trifluoromethylation of benzohydrazides. Nat. Commun. 10, 769 (2019).

Zhang, Z., Stateman, L. M. & Nagib, D. A. δ C–H (hetero)arylation via Cu-catalyzed radical relay. Chem. Sci. 10, 1207 (2019).

Liu, Z. et al. Copper-catalyzed remote C(sp3)-H trifluoromethylation of carboxamides and sulfonamides. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 58, 2510 (2019).

Wang, S., Guo, L.-N., Wang, H. & Duan, X.-H. Alkynylation of tertiary cycloalkanols via radical C-C bond cleavage: a route to distal alkynylated ketones. Org. Lett. 17, 4798 (2015).

Tang, X. & Studer, A. α-Perfluoroalkyl-β-alkynylation of alkenes via radical alkynyl migration. Chem. Sci. 8, 6888 (2017).

Gao, Y., Mei, H., Han, J. & Pan, Y. Electrochemical alkynyl/alkenyl migration for the radical difunctionalization of alkenes. Chem. Eur. J. 24, 17205 (2018).

Ren, R., Wu, Z., Xu, Y. & Zhu, C. C−C Bond‐forming strategy by manganese‐catalyzed oxidative ring‐opening cyanation and ethynylation of cyclobutanol derivatives. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 55, 2866 (2016).

Xu, Y., Wu, Z., Jiang, J., Ke, Z. & Zhu, C. Merging distal alkynyl migration and photoredox catalysis for radical trifluoromethylative alkynylation of unactivated olefins. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 56, 4545 (2017).

You, X. et al. Nickel-catalyzed [2+2+2] cycloaddition of alkyne-nitriles with alkynes assisted by Lewis acids: efficient synthesis of fused pyridines. Chem. Eur. J. 22, 16765 (2016).

Nicola, T., Vieser, R. & Eberbach, W. Anionic cyclizations of pentynones and hexynones: access to furan and pyran derivatives. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 52, 527–538 (2000).

Acknowledgements

We thank EPFL (Switzerland), the Swiss National Science Foundation (SNSF 20020_155973; SNSF 20021_178846) for financial support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Z.L., R.O.T.-O., Q.W. and J.Z. conceived and designed the experiments. Z.L. and R.O.T.-O. carried out the experiments. Z.L., R.O.T.-O., Q.W. and J.Z. interpreted the results and co-wrote the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Peer review information Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, Z., Torres-Ochoa, R.O., Wang, Q. et al. Functionalization of remote C(sp3)-H bonds enabled by copper-catalyzed coupling of O-acyloximes with terminal alkynes. Nat Commun 11, 403 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-14292-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-14292-2

This article is cited by

-

Deacylation-aided C–H alkylative annulation through C–C cleavage of unstrained ketones

Nature Catalysis (2021)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.