Abstract

Surface plasmon resonance (SPR) effect of noble metal nanoparticles (NPs) for photocatalysis has a significant enhancement. In this system, a plasmonic ternary hybrid photocatalyst of Ag/AgBr/g-C3N4 was synthetized and used in water splitting to generation H2 under visible light irradiation. 18%Ag/AgBr/g-C3N4 showed the highest photoactivity, with the efficiency of hydrogen generation as high as 27-fold to that of pristine g-C3N4. Compared to simple mixture of Ag/AgBr and g-C3N4, hetero-composite Ag/AgBr/g-C3N4 showed a higher photoactivity, even though they contained same content of Ag/AgBr. We find that significant factors for enhancing properties were the synergistic effect between Ag/AgBr and g-C3N4, and the light absorption enhancing by SPR effect of Ag NPs. Ag/AgBr NPs firmly anchored on the surface of g-C3N4 and their high dispersion were also responsible for the improved activity and long-term recycling ability. The structure of Ag/AgBr/g-C3N4 hybrid materials and their enhancement to photocatalytic activity were discussed. Meanwhile, the possible reaction mechanism of this system was proposed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Increasing attentions to environment and energy crises have spurred intense research on solar energy transform and utilization1,2,3. Hydrogen as an environmentally friendly energy source has gained more and more attention. Photocatalytic water splitting to produce hydrogen by harnessing sunlight holds particular promise as this process is economic and environmentally friendly4,5,6,7. Recent years, graphene-like carbon nitride (g-C3N4) material as a polymeric compound photocatalyst has attracted considerable attention for hydrogen generation and degradation ability of organic pollutants under visible light irradiation8,9,10,11,12,13. As a robust and stable visible-light-driven photocatalyst with the appropriate band energy, nontoxicity and abundance properties, it also has good chemical stability, attractive electronic structure and medium-bandgap of approximately 2.7 eV8,14,15. Meanwhile, g-C3N4 is easily-obtained via a one-step method from cheap feed stocks, such as cyanamide16, dicyandiamide17, melamine18, thiourea19 and urea20. Although g-C3N4 emerges as a good candidate for solar catalysis because of its unique physicochemical properties. While, g-C3N4 also suffers from some drawbacks, such as low visible-light utilization (only the light with the wavelength < 460 nm can be absorbed) and rapid recombination of photogenerated charges. Hence, various approaches have been proposed to overcome these glitches21,22,23,24,25, such as metallic and non-metallic doping, design of heterojunctions, morphology control, and construction of C or N defects. Among these, it is a key remedy to choose appropriate noble metals as co-catalyst26,27. Pt as a most efficient co-catalyst is used to modify g-C3N4 to enhance charge separation in photocatalytic process28,29. However, the scarcity and high cost of Pt seriously impede its extensive applications.

Recently, many studies have found that Ag as surface plasmon resonance (SPR) material which can be triggered by visible light is introduced into photocatalyst system. They can efficiently convert solar energy into chemical energy under visible light irradiation30. Meanwhile, the introduction of AgX (X = Cl, Br, I) to semiconductor photocatalysts can enhance photogeneration charge separation efficiency. Three-component plasmonic photocatalysts based on Ag/AgX (X = Cl, Br, I) have improved stability and photocatalytic performance of single photocatalyst31,32,33,34. For instance, photocatalysts decorated by Ag/AgCl exhibit excellent visible light absorption performance due to the synergistic effect of Ag/AgCl and SPR effect of Ag NPs32,35, Ag@AgCl36, Ag/AgCl/TiO2 nanotube arrays37 and Ag/AgCl/Al2O338 showed high activity in degradation of organic pollutants (MO and MB) under visible light irradiation; Ag/AgBr hybrids display a synergistic effect between semiconductors and plasmonic metals and exhibit a considerably high photocatalytic performance for pentachlorophenol degradation39. The dispersion and stability of Ag/AgI can be further enhanced by compounding with other semiconductors34. Thus, developing semiconductor photocatalysts including inexpensive metals and their compounds with excellent light-trapping performance, high charge separation efficiency, and favorable recycling capabilities is extremely important40,41,42,43.

Considering the proper band gap and conduction band (CB) position of g-C3N4 and AgBr, we constructed a ternary photocatalyst with metal Ag and AgBr NPs supported on g-C3N4 (shown as Fig. 1). For the first time, we used this plasmonic ternary photocatalyst to generate H2 under visible light irradiation which demonstrated high efficiency for photocatalytic water splitting. In this system, room temperature ionic liquid ([Amin]Br) was used as Br− source and space steric agent in preparing Ag/AgBr/g-C3N4 composite. Ag/AgBr NPs were highly dispersed on g-C3N4 nanosheets surface. This kind of distinctive Ag/AgBr/g-C3N4 ternary hybrid photocatalyst has substantially overcome the shortcomings compared with the single components and realized strong light absorption, high charge-separation efficiency, perfect photocatalytic stability, and relative strong redox ability44,45. The mechanism of Ag/AgBr/g-C3N4 hetero-composites photocatalysis was further discussed in details. Ag NPs with strong UV-vis absorption could be excited by visible incident light, thereby resulting in SPR effect in this heterostructure system to enhance light absorption. Considering band gap matching of AgBr and g-C3N4, the separation efficiency of photoexcited charges was considerably improved.

Schematic diagram of hydrogen production from Ag/AgBr/g-C3N4. (AgBr nanoparticles anchored by Ag nanoparticles are attached to g-C3N4 surface. Photogenerated electrons migrated to AgBr conduction band, and were enriched on the surfaces of AgBr nanoparticles to produce hydrogen on the surface of AgBr, while the holes were enriched in the g-C3N4 valence band, where they reacted with TEOA and OH−).

Results and Discussion

Morphology and component analysis

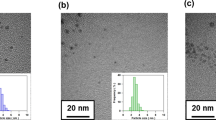

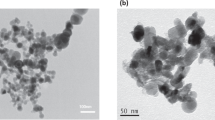

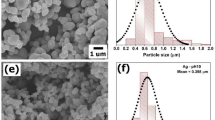

The microscopic and structural morphologies of pure g-C3N4 and 18%Ag/AgBr/g-C3N4 were revealed by scanning electron microscope (SEM) and transmission electron microscopy (TEM), shown in Fig. 2. The representative structure of as-obtained g-C3N4 comprised large aggregates of 2-D nanosheet with irregular morphology and nonuniform dimensions (Fig. 2a). TEM image shown in Fig. 2b displayed smooth and flat layers in pure g-C3N4 sample. However, after ultrasonic treatment, some single nanosheets (Fig. 2c) emerged in g-C3N4 sample, although some aggregates were still present. After impregnation into AgNO3 and [Amim]Br solutions, the aggregated g-C3N4 was peeled into thin layers, and many AgBr NPs were inserted into the layers, as shown by red circles in Fig. 2c,d. This nanosheet microstructure with large specific surface area could provide more sites for formation of Ag/AgBr particles. SEM and TEM images of Ag/AgBr/g-C3N4 were obviously different from those of bare g-C3N4. Zero-dimensional Ag/AgBr NPs anchored on g-C3N4 surface formed heterojunction structure. As shown in Fig. 2d, Ag/AgBr NPs with the size ranging from 20 nm to 90 nm were dispersed well on the g-C3N4 surface with insignificant aggregation. At the same time, the particle size distribution was statistically analyzed. The statistical results showed that the size of Ag/AgBr particle was dispersed mainly in the range of 40 to 60 nm (shown as the insert in Fig. 2d). Such even dispersion indicated a strong anchoring effect of g-C3N4 to Ag/AgBr nanocrystals. Obtained Ag/AgBr/g-C3N4 nanostructure could fully utilize Ag/AgBr outer surfaces and the interfaces between Ag/AgBr and g-C3N4, which was very important to enhance photoactivity of the hybrid. However, when Ag/AgBr content reached 21%, the large amount of Ag/AgBr on g-C3N4 surface resulted in its agglomeration, as shown in Fig. S1d. The size of Ag/AgBr particles increased, which would decrease its photoactivity. Meanwhile, Ag/AgBr without g-C3N4 showed a large scale ranging from 100 nm to >700 nm with substantial agglomeration, as shown in Fig. S1e. And the photocatalysts with other contents were shown in Fig. S1a–c.

Energy dispersive spectrometer (EDS) and elemental mapping data of 18%Ag/AgBr/g-C3N4 were also measured, shown in Fig. 3. The EDS result revealed that sample mainly contained four elements (i.e., C, N, Ag and Br) after removing other element introduced from environment. As shown in Fig. 3a, a small amount of O was detected due to the trace adsorption of O2 onto the sample surface. The weight percent of C, N, Ag, Br for 18%Ag/AgBr/g-C3N4 nanocomposite were theoretical calculated and quantitatively analyzed. Similar results were obtained (32.1, 49.9, 10.3 and 7.7%; 32.4, 49.3, 10.8, 7.1%, respectively). To verify the elemental distribution of obtained 18%Ag/AgBr/g-C3N4 hybrid, elemental mapping of the sample was also demonstrated, as shown in Fig. 3c–f. The results showed that Ag and Br were homogeneously distributed on g-C3N4 nanosheet host surface. The distribution of O element was also tested, and shown in Fig. S2. Fourier-transform infrared (FT-IR) spectra and X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) were also conducted to analyze composite composition and structure, respectively (Figs. S3 and S4). All these results showed that Ag and Br were presented in the form of Ag/AgBr. Thus, Ag/AgBr NPs were dispersed on g-C3N4 surface uniformly and tend to combine with g-C3N4 thin nanosheets firmly and then formed heterojunction systems. Meanwhile, high-resolution XPS spectrum of O elemental was also tested, and shown in Fig. S5.

Phase structure analyses

The crystalline structures of all obtained photocatalysts were characterized by X-ray diffraction (XRD) and shown in Fig. 4. Typical XRD pattern of g-C3N4 (Fig. 4a) showed an intense diffraction peak at 2θ = 27.7°, which could be indexed as (002) interlayer-stacking peak corresponding to an interlayer distance of d = 0.32 nm, while the peak at 13.0° was (100) plane of hexagonal g-C3N4 (JCPDS card No. 87–1526), which represented an in-plane structural packing motif with a period of 0.675 nm16. As shown in Fig. 4b–f, the patterns corresponded to photocatalysts with an increasing Ag/AgBr mass ratio (5%, 10%, 15%, 18%, and 21%) were exhibited. After assembling Ag/AgBr NPs with g-C3N4 nanosheets, several new diffraction peaks (marked with “♥”) were observed at 26.5°, 30.7°, 44.1°, 52.3°, 54.8°, 64.3° and 73.0°, which were assigned to (111), (200), (220), (331), (222), (400) and (420) planes of AgBr crystal (JCPDS No. 06–0438)33,39,46. The diffraction peaks (marked with “◆”) of the metallic Ag at 37.8° and 77.4° were detected, which could be assigned to (111) and (311) crystal faces corresponding to the pattern of crystalline Ag, respectively (JCPDS No. 65–2871)46. The intensity of AgBr peaks were enhanced gradually with the increasing of AgBr amount, while the intensity of g-C3N4 peak decreased. The intensity of g-C3N4 peak decreasing regularly indicated that Ag/AgBr was compounded onto g-C3N4 surface. No other impurity phase was observed in the pattern of Ag/AgBr/g-C3N4. Thus, Ag/AgBr/g-C3N4 samples contained three phases, namely, Ag, AgBr and g-C3N4.

Optical properties of the composites

The optical properties of photocatalysts was determined by UV-vis diffuse reflectance spectrum (UV–vis DRS). As shown in Fig. 5A, pure g-C3N4 showed a typical semiconductor absorption in the range of 250–450 nm, which was rooted the charge-transfer from valence band (VB, occupied by N2p orbitals) to conduction band (CB, formed by C2p orbitals)16,47. The absorption thresholds of g-C3N4 was approximately 455 nm (shown as Fig. 5A(a)). Spectra of hybrid composites with different loading amount of Ag/AgBr (5%, 10%, 15%, 18% and 21%) were shown in Fig. 5A(b–f), the absorption thresholds of composites showed a negligible shift. The light absorption of Ag/AgBr/g-C3N4 was significantly increased in the wavelength range of 500–800 nm, and the absorption intensities increased according to the increase of Ag/AgBr content, which were attributed to SPR effect of Ag NPs. As shown in Fig. 5A(g), Ag/AgBr showed a strong absorption in all test region, thereby corresponding to the increasing by SPR effect of Ag NPs48. Meanwhile, the spectrum of AgBr was also tested and showed in Fig. 5A(h), the thresholds of AgBr was around 496 nm. It just showed a slight red shift to some extent compared to g-C3N4. We obtained that the enhancing absorption of composite photocatalysts in visible light region was mainly obtained from SPR effect of Ag. Meanwhile, band gap (Eg) of g-C3N4 and AgBr could be calculated by Eq. (1) and obtained from UV-vis spectra, as follows49:

Where α is absorption coefficient, hν is photon energy, and A is proportionality constant50. Given the optical transition type of a semiconductor, n value was 1 (direct transition) or 4 (indirect transition). The n values of g-C3N4 and AgBr were both 451,52. Hence, the plot of (αhν)1/2 versus photon energy (hν) for g-C3N4 and 18%Ag/AgBr/g-C3N4 was obtained, as shown in Fig. 5B. As a result, the band gap energies of AgBr and g-C3N4 were estimated from the plot of (αhν)1/2 versus energy (hν) curve. Thus, Eg values of AgBr and g-C3N4 were 2.50 and 2.72 eV (Fig. 5B), respectively.

(A) UV-vis absorption spectra (in the diffuse reflectance spectra mode and the inset was the photo of samples) of (a) g-C3N4, (b) 5%Ag/AgBr/g-C3N4, (c) 10%Ag/AgBr/g-C3N4, (d) 15%Ag/AgBr/g-C3N4, (e) 18%Ag/AgBr/g-C3N4, (f) 21%Ag/AgBr/g-C3N4, (g) Ag/AgBr and (h) AgBr; and (B) Plots of (a) g-C3N4 and (b) 18%Ag/AgBr/g-C3N4 ((ahν)1/2 Vs. hν).

Visible light photocatalytic activities and evaluation of stability

The amount of H2 production for all photocatalysts was detected with triethanolamine (TEOA) as sacrificial reagent under visible light irradiation illumination (λ > 420 nm). The peak areas of different samples at different test times were obtained with gas chromatograph (GC) test. According to the standard curve y = 165546x (as shown in Fig. S6; R2 = 0.9998, y: peak area value, x: H2 volume), the amount of H2 was calculated. Under the same condition, the control experiments were conducted. The test results indicated that insignificant amount of H2 was detected without photocatalysts, light irradiation or H2O. Meanwhile, the amount of H2 using Ag/AgBr as photocatalyst was also conducted under the same condition, and a slight amount of H2 was detected. The corresponding results for time-dependent (Fig. 6A) and average (Fig. 6B) photoinduced H2 evolution for different photocatalysts were shown (the values were listed in Table S1). H2 production using bare g-C3N4 as photocatalyst was 59.1 μmol g−1 h−1, which was significantly lower than that of heterogeneous catalysts Ag/AgBr/g-C3N4 with the highest efficiency of 1587.6 μmol g−1 h−1 that was attained using 18%Ag/AgBr/g-C3N4 as photocatalyst. This result was approximately 27-fold to that of pure g-C3N4. The low photocatalytic ability of pure g-C3N4 was due to its relatively poor visible light absorption performance and low photogenerated charge-separation efficiency. Photogenerated e− of g-C3N4 was extremely difficult to transfer to active sites and unable to participate in H2 production53,54. Compared with other g-C3N4-based photocatalysts, H2 production rate of Ag/AgBr/g-C3N4 was significantly enhanced (the comparison results were shown in Table 1), which was ascribed to plasmonic effect of Ag NPs for enhancing absorption in visible light region and the high charge separation efficiency of heterostructures54,55,56,57. Pure Ag/AgBr with substantial agglomeration (with the size from 100 nm to >700 nm) showed a poor photocatalytic activity (24.1 μmol g−1 h−1). Nevertheless, bulk Ag/AgBr showed a high absorption performance in visible light region. Considering its heavy agglomeration, only few active sites were found, and photogenerated charges transferring to photocatalyst surfaces to reduce H+ became extremely difficult. Meanwhile, photogenerated charge separation efficiency decreased significantly because e− and h+ needed to move long distance inside of bulk Ag/AgBr and additional charge recombination centers were also observed.

(A) Time courses of photocatalytic H2 (B) average rate of H2: (a) g-C3N4, (b) 5%Ag/AgBr/g-C3N4, (c) 10%Ag/AgBr/g-C3N4, (d) 15%Ag/AgBr/g-C3N4, (e) 18%Ag/AgBr/g-C3N4, (f) 21%Ag/AgBr/g-C3N4 and (g) Ag/AgBr under visible light irradiation; (C) Recyclability of 18%Ag/AgBr/g-C3N4 in 5-cycle experiments for H2 evolution under visible light irradiation; (D) Time courses of photocatalytic H2 (insert: the average rate of H2): (a) g-C3N4, (b) 18%Ag/AgBr/g-C3N4, (c) mixture of g-C3N4 and Ag/AgBr(18 wt%).

Ag/AgBr content also exhibited a considerable influence on H2 evolution efficiency. As Ag/AgBr content increased, H2 production rate increased first and then decreased. When Ag/AgBr content was above 21%, an excessive amount of Ag/AgBr distributing on the limit g-C3N4 surface began to agglomerate, and the size became greater than 200 nm. The tight binding and interaction between g-C3N4 and Ag/AgBr disappeared, and heterostructure was no longer observed. Ag and AgBr became the combination centers of photogenerated charges, and charge separation efficiency was significantly decreased.

The stability and reusability of 18%Ag/AgBr/g-C3N4 nanocomposite as a representative were evaluated with a recycling experiment for 5 h, and the corresponding results were shown in Fig. 6C (Table S2). The results indicated that 18%Ag/AgBr/g-C3N4 hetero-structure photocatalyst showed a high stability in photocatalytic H2 production. In whole 5-cycle experiment, the amount of H2 obtained increased steadily with an extension during the reaction time, and total H2 produced showed insignificant reduction. As a comparison, the mixture of g-C3N4 and Ag/AgBr with the same content (18 wt%) was tested to conduct H2 production under the same condition. As shown in Fig. 6D (the corresponding results were listed in Table S3), the mixture showed a similar photocatalytic activity with that of pure g-C3N4. The mixture did not show a high efficiency for H2 production when it was used as photocatalyst (52.5 μmol g−1 h−1). This mixture was only obtained via a simply mechanical mixing of g-C3N4 and Ag/AgBr, they could not act synergistically. Photogenerated charges separation efficiency could not be increased to enhance photocatalyst activity. Meanwhile, the stability of 18%Ag/AgBr/g-C3N4 catalyst was further verified through XRD and SEM after 5 cycles of photocatalytic experiments (Figs. S7 and S8). The XRD result showed that the positions and intensity of peaks remained consistent, thereby indicating that the crystal structure of photocatalyst did not change significantly after photocatalytic experiments. SEM result revealed that morphology was steady. After 5-cycle photocatalytic test, Ag/AgBr NPs were still anchored firmly on g-C3N4 surface, thereby suggesting that the hetero-composite had high stability for photohydrogen production. Such high stability resulted from the formation of heterostructure between g-C3N4 and Ag/AgBr.

Charge transfer properties

Photogenerated electron-hole separation efficiency of photocatalyst was an extremely important factor for photocatalytic activity, that was, high separation efficiency indicated high photocatalytic activity. Photoluminescence (PL) technique could effectively investigate migration, transfer, and recombination processes of photogenerated electron-hole pairs in semiconductors. PL spectra of photocatalysts should be investigated because only separated photo-induced e− could be involved in subsequent photoreduction H2 evolution. PL emission spectra of photocatalysts were measured with an excitation light of λ = 315 nm, and the results were shown in Fig. 7A. Pure g-C3N4 had a wide and strong peak in PL spectrum excited at approximately 438 nm17,19,58. For Ag/AgBr/g-C3N4 hybrid materials, the position of emission peaks was similar to that of bare g-C3N4, but the intensity decreased significantly. This result indicated that Ag/AgBr/g-C3N4 composites had a considerably lower recombination rate of photogenerated charge carriers19,59,60. This result indicated that introduction of Ag/AgBr could significantly inhibit the recombination of photogenerated charges, which indicated that photogenerated e− and h+ in Ag/AgBr/g-C3N4 heterostructure photocatalyst contained higher separation efficiency than those in bare g-C3N4. However, when Ag/AgBr content reached 21%, emission intensity of composites began to increase furtherly, thereby decreasing the photoactivity of photocatalyst. This phenomenon was due to the fact that excessive Ag/AgBr caused agglomeration of particles, thereby producing increased compound centers.

(A) Photoluminescence spectra: (a) g-C3N4, (b) 5%Ag/AgBr/g-C3N4, (c) 10%Ag/AgBr/g-C3N4, (d) 15%Ag/AgBr/g-C3N4, (e) 18%Ag/AgBr/g-C3N4, (f) 21%Ag/AgBr/g-C3N4; (B) Photocurrent responses: (a) g-C3N4, (b) 5%Ag/AgBr/g-C3N4, (c) 10%Ag/AgBr/g-C3N4, (d) 15%Ag/AgBr/g-C3N4, (e) 18%Ag/AgBr/g-C3N4, (f) 21%Ag/AgBr/g-C3N4; and (C) EPR spectra: (a) g-C3N4, (b) 18%Ag/AgBr/g-C3N4.

Photoelectrochemistry test could provide another powerful mean to study excitation and transportation of e−. To supply an evidence supporting the coupling of Ag/AgBr and g-C3N4 played an important role in photocatalytic H2 evolution, we tested photocurrent responses of g-C3N4 and Ag/AgBr/g-C3N4 with different contents and exhibited three on/off cycles of irradiation (Fig. 7B). Under Xe lamp irradiation, all tested working electrodes photocurrent responses were sharply increased once light source was turned on, and generated photocurrents were stable and reproducible during three on/off intermittent irradiation tests. Under the same test conditions, Ag/AgBr/g-C3N4 composites showed a higher photocurrent density than that of bare g-C3N4. The composite electrodes with 18% content of Ag/AgBr and pure g-C3N4 presented the highest (0.87 μA cm−2) and the lowest (0.13 μA cm−2) photocurrent density. Meanwhile, photocurrent responses of Ag/AgBr/g-C3N4 electrodes with other contents were between two extreme values mentioned above. The photocurrent density of Ag/AgBr/g-C3N4 composite electrodes increased gradually with the increase in Ag/AgBr content until the content achieved the optimized value and then began to decrease. The photocurrent results further confirmed that Ag/AgBr/g-C3N4 composites had higher separation efficiency of photogenerated electron-hole pairs than that of bare g-C3N4. This result indicated that Ag/AgBr had been effectively combined onto g-C3N4 surface, thereby leading to high separation efficiency of photogenerated electron-hole pairs in g-C3N4. The current density of composite electrode would not be further increased when its Ag/AgBr content reached the optimal value (18%). The enhancing effect to photocurrent density was impeded by the agglomeration of excess Ag/AgBr. Hence, separation efficiency of photogenerated charges and photocatalytic activity decreased. Ag NPs introduced by Ag/AgBr as a “trap” could capture a part of photogenerated electrons, showing in the results of photocurrent of doped catalyst electrodes there were a tailing phenomenon, thereby the introduction of Ag/AgBr into g-C3N4 further improved separation efficiency of photogenerated charge61,62. These results were consistent with the results of PL spectra.

Room-temperature electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) spectra of g-C3N4 and Ag/AgBr/g-C3N4 were recorded (Fig. 7C). Both g-C3N4 and Ag/AgBr/g-C3N4 exhibit only one single lorentzian paramagnetic absorption signal with g value of 2.003, which was attributed to unpaired electrons in sp2-hybridized carbon atoms within the π-conjugated aromatic system63,64. However, Ag/AgBr/g-C3N4 showed an enhanced EPR signal as compared to g-C3N4, indicating the presence of more unpaired electrons in localized heterocyclic ring of hetero-catalyst due to the defects causing by coupling of Ag/AgBr65,66. That suggested more efficient generation of photoelectrons arising from composite photocatalyst67.

Mechanism underlying enhanced photoactivity

On the basis of results and analysis above, the mechanisms for photoreduction hydrogen evolution from water splitting in this system was proposed. The effects of enhancement by introducing Ag/AgBr into g-C3N4 forming a hetero-structure plasmonic photocatalyst were illustrated in Fig. 8. The band edge potential position played an important role in studying the flowchart of photoexcited charges. The potentials of CB and VB edges could be evaluated by Mulliken electronegativity theory, as follows68:

where X is absolute electronegativity of the atom semiconductor (the geometric mean of absolute electronegativity of constituent atoms: the arithmetic mean of atomic electro affinity and the first ionization energy), and the X values for g-C3N4 and AgBr were 4.72 eV and 4.90 eV, respectively32,69; Ec is the energy of free e− with the hydrogen scale (Ec = 4.5 eV); Eg is the band gap of semiconductor, and the band gap values of g-C3N4 and AgBr were 2.72 and 2.50 eV, respectively. As a result, the CB and VB values of g-C3N4 were -1.14 eV, 1.58 eV; the corresponding values of AgBr were -0.85 eV, 1.65 eV respectively.

Schematic of the energy diagram and charge separation in ternary hybrid photocatalyst of Ag/AgBr/g-C3N4 photocatalysts under visible-light irradiation. (When the photocatalyst is excited by visible light irradiation, g-C3N4, AgBr and Ag were simultaneously excited to generate photogenerated electrons. Photogenerated electrons have three transmission paths: e− on g-C3N4 CB could migrate to CB of AgBr; e− generated by Ag nanoparticles with SPR effect also migrate to AgBr; meanwhile, a part of e− from AgBr CB migrated back to Ag nanoparticles, which could ensure the stability of the catalyst. Finally, e− were enriched on the surface of AgBr particles and participated in the reduction reaction to produce H2).

As we know, SPR effect of noble metal nanocomposites produces a strong local electrostatic electric field, which could effectively suppress electron-hole recombination and improve efficiency of electron-hole separation40,69. In this system, the enhancement of composite photocatalytic performance was mainly attributed to its high separation efficiency due to easy transfer of e− and h+ on heterojunction interfaces and the enhancement of light absorption caused by plasmon effect of Ag NPs70. When AgBr NPs were combined with g-C3N4, these two different semiconductor materials were connected closely, and heterojunction structure was obtained, which resulted in an effective photogenerated charge separation between these two semiconductors. Meanwhile, Ag NPs with a strong absorption around 450 nm adhering on AgBr surface could give out e− by absorbing visible light due to its SPR effect, thereby further increasing photocatalytic activity by enhancing light absorption71. In this photocatalyst system, both g-C3N4 and AgBr could be excited simultaneously to generate e− and h+ under visible light irradiation. Simultaneously, Ag NPs could absorb visible light and generate e− due to its SPR effect20,39,51,59. Photogenerated e− in g-C3N4 CB could easily transfer to AgBr CB, and h+ in AgBr VB could transfer to g-C3N4VB due to their matched energy levels. Electrons could transfer from Ag to AgBr because n-type AgBr semiconductor had a higher work function (AgBr = 5.3 eV, Ag = 4.25 eV) and a lower Fermi level than that of Ag39. e− transferred from photoexcited metal Ag to CB of AgBr, thereby leaving positively charged Ag NPsn+ 39,72,73. The separated e− could react with H2O to generate H2. At the same time, parts of e− tended to be involved in the positive potential Ag NPsn+ and combined with Ag NPsn+ to form Ag NPs and sustained the stability of photocatalyst74,75. Finally, generated h+ could react with TEOA and OH− on VB of g-C3N4.

In conclusion, polymeric compound g-C3N4 composed of graphitic planes that were constructed from tri-s-triazine units; when Ag/AgBr particles were loaded on g-C3N4 surface, Ag/AgBr/g-C3N4 interface was formed, which could effectively suppress photo-generated charges recombination, and e− generated from g-C3N4 could transfer to Ag/AgBr nanoparticles efficiently. The synergistic effects of Ag/AgBr and g-C3N4 coupling enhanced electron transfer between the interfaces of Ag/AgBr and g-C3N4, thereby enhancing photocatalytic performance of Ag/AgBr/g-C3N4 photocatalysts. g-C3N4 could also act as a substrate, which was helpful in assembling Ag/AgBr on g-C3N4 surface to form hetero-structure. This nanostructure was especially favorable for photocatalytic applications because highly dispersion nanoparticles and thin nanosheet could decrease the recombination amount of photo-generated charges in inner of Ag/AgBr and g-C3N4. Meanwhile, thin nanosheet of g-C3N4 allowed easy transfer of photogenerated e− to g-C3N4 surface. Ag/AgBr that was formed on g-C3N4 surface in situ, significantly enhanced the visible light absorption of hybrid materials, thereby indicating that it could enhance visible-light energy utilization.

Conclusions

We synthetized a ternary visible-light-response plasmonic photocatalyst Ag/AgBr/g-C3N4 by means of green and handy route. Prepared metal-semiconductor ternary composite photocatalyst exhibited a high visible-light photocatalytic activity for water splitting to generation hydrogen without Pt co-catalyst. According to experiment results, 18%Ag/AgBr/g-C3N4 showed the highest photoactivity, 1587.6 μmol g−1 h−1. Such excellent performance should be attributed to the distinctive heterojunction system, which could successfully transfer electron generated from g-C3N4 resulting in the suppression of electron-hole recombination. The coupling of these materials solved the problems of high electron-hole recombination rate of g-C3N4 and the large particle size of Ag/AgBr at the same time. Meanwhile, light absorption was also enhanced due to SPR effect of Ag NPs. And what’s more, this study opens up new insights into the design and preparation of novel ternary hybrid photocatalysts with high photoactivity and further utilizations in the field of energy and environment.

Experimental

Preparation

Urea (chemical grade) was purchased from Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Beijing Co., Ltd. 1-Allyl-3-methylimidazolium bromide ([Amim]Br, 97%), silver nitrate (AgNO3, 99%) and triethanolamine (TEOA, 98%) were obtained from Aladdin Industry Corporation. All of these chemicals were used as they were gotten. Deionized water was obtained from pure water system (GWA-UN, Beijing, China).

Pure g-C3N4 was prepared via a simple calcined method, with urea as precursor76. First, 10 g of urea was placed into an alumina crucible with a lid, heated to 600 °C at a rate of 5 °C min−1, and maintained at this temperature for 4 h in a static air atmosphere. Then, the product was collected when cooled down to room temperature slowly. Light-yellow sample was dried at 50 °C after washing with water and ethanol. The obtained g-C3N4 was grinded for further experiments.

Ag/AgBr/g-C3N4 composites were synthetized by an improved deposition-precipitation, followed in situ photoreduction77. Typically, 85.6 mg as-prepared g-C3N4 powders were immersed into 40 mL of deionized water and sonicated for 60 min. Then, AgNO3 solution (17 mg, 20 mL) was dropped under dark condition, and amino groups on g-C3N4 sheet surface could coordinate with Ag ions tightly. Afterward, [Amim]Br solution (20.3 mg, 20 mL) was added into the g-C3N4 suspension by dropping under vigorous stirring and reacting for 4 h under dark condition. Considering the steric hindrance of [Amim]+, AgBr was obtained slowly by the action between Br− and Ag+. Then, the reaction system was irradiated by a 500 W high-pressure Hg lamp (λ = 365 nm) for 15 min under stirring to obtain a spot of Ag NPs. The precipitate was collected by centrifugation, washed with ethanol and water several times, and vacuum dried at 60 °C for 12 h. Finally, Ag/AgBr/g-C3N4 composite with a theoretical mass ratio of Ag/AgBr to g-C3N4 at 18:82 was obtained and nominated as 18%Ag/AgBr/g-C3N4. Ag/AgBr/g-C3N4 composites with other Ag/AgBr content were prepared by changing the amount of [Amim]Br and AgNO3, and named as 5%Ag/AgBr/g-C3N4, 10%Ag/AgBr/g-C3N4, 15%Ag/AgBr/g-C3N4, 21%Ag/AgBr/g-C3N4. Ag/AgBr was prepared by a similar method without g-C3N4. AgBr was synthesized without g-C3N4 and UV light irradiation.

Characterization

The morphologies were determined by field-emission scanning electron microscope (FESEM, JSM-7500F, Electron Optics Laboratory Co., Ltd., Japan) and transmission electron microscopy (TEM, Tecnai G2 20 S-TWIN, FEI, USA). Energy dispersive spectroscopy (EDS) data were collected by FESEM equipped with EDS accessories (INCA Energy 250, Oxford, USA). The crystalline structure of samples was analyzed by X-ray diffraction (XRD, XRD-6000, Shimadzu, Japan). The survey and high-resolution spectra data of photocatalysts were obtained from X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS, ESCALAB 250Xi, Thermo Fisher, USA). The absorption spectra under a UV-vis diffuse reflectance spectrum (UV-vis DRS) mode were recorded on UV-vis spectrophotometer (UV-3600, Shimadzu, Japan) in a range of 250–800 nm. Fourier-transform infrared (FT-IR) spectra were conducted on Nicolet iS10 IR spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, USA). The photoluminescence (PL) data were recorded by Hitachi F-4500 fluorescence spectrometer (Japan, photomultiplier tube voltage of 400 V) with a scanning speed of 240 nm min−1. The electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) spectra were carried out by A300-10/12 (Bruker, Germany).

Photocatalytic activity of H2 evolution

The activity of as-prepared photocatalysts was verified through photocatalytic H2-evolution experiments. First, 50 mg photocatalyst dispersing in 100 mL of solvent (90 mL of deionized water and 10 mL of TEOA) was sealed into a top-irradiation quartz vessel. Second, the reaction vessel was installed to gas-closed circulation system (Labsolar-6A, Beijing Perfectlight Technology Co., Ltd., China) and vacuum pumped to avoid the adverse effects of dissolved air in the system. Third, a 300 W Xe lamp (light intensity: 100 mW cm−2; Microsolar300, Beijing Perfectlight Technology Co., Ltd., China) with a 420 nm cut-off filter was turned on to illuminate the system under stirring. The amount of gas was detected in situ through an online gas chromatograph (type: GC7900, Tech-comp Shanghai Co., Ltd., China) with Ar as carried gas to determine the amount of produced H2.

Photoelectrochemical measurement

The working electrode was prepared according to our previous method78. Briefly, 230 μL of water, 250 μL of ethanol, and 20 μL of Nafion (5 wt%) were mixed and stirred for 20 min. Second, 10 mg as-prepared photocatalyst was placed into the solution above, dispersed ultrasonically for 30 min, and then stirred overnight. Afterward, 20 μL of the resulting colloidal dispersion was dispersed onto the surface of clear ITO (with a size of 1 × 1 cm). Lastly, the electrodes were placed into a culture vessel and dried under an ambient temperature for 4 h. The transient photocurrent was obtained from a standard three-electrode system on an electrochemical workstation (CHI 660D, Shanghai Chen Hua Instrument Co., Ltd., China); Pt plate was used as counter electrode, and Ag/AgCl electrode (in saturated KCl solution) served as a reference electrode. A solar simulator illumination (light intensity: 100 mW cm−2, CXE-350, Photoelectric Instrument Factory of Beijing Normal University, China) was used as the light source.

References

Kapdan, K. & Kargi, F. Bio-hydrogen production from waste materials. Enzyme Microb. Technol. 38, 569–582 (2006).

Cabán-Acevedo, M. et al. Efficient hydrogen evolution catalysis using ternary pyrite-type cobalt phosphosulphide. Nat. Mater. 14, 1245–1251 (2015).

Hoang, S., Berglund, S. P., Hahn, N. T., Bard, A. J. & Mullins, C. B. Enhancing visible light photo-oxidation of water with TiO2 nanowire arrays via contreatment with H2 and NH3: synergistic effects between Ti3+ and N. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 3659–3622 (2012).

Godin, R., Wang, Y., Zwijnenburg, M. A., Tang, J. W. & Durrant, J. R. Time-resolved spectroscopic investigation of charge trapping in carbon nitrides photocatalysts for hydrogen generation. J. Am. Che. Soc. 139, 5216–5224 (2017).

Jamesh, M. I., Kuang, Y. & Sun, X. Construction earth-abundant 3D nanoarrays for efficient overall water splitting-a review. ChemCatChem 11, 1550–1575 (2019).

Ni, M., Leung, M. K. H., Leung, D. Y. C. & Sumathy, K. A review and recent developments in photocatalytic water-splitting using TiO2 for hydrogen production. Rennew. Sust. Energ. Rev. 11, 401–425 (2007).

Inahori, H., Mori, Y. & Matano, Y. Nanostructured artificial photosynthesis. J. Photoch. Photobio. C 4, 51–83 (2003).

Cao, S., Low, J., Yu, J. & Jaroiec, M. Polymeric photocatalysts based on graphitic carbon nitride. Adv. Mater. 27, 2150–2176 (2015).

Zhao, Z., Sun, Y. & Dong, F. Graphitic carbon nitride based nanocomposites: a review. Nanoscale. 7, 15–37 (2015).

Katsumata, H., Sakai, T., Suzuki, T. & Kaneco, S. Highly efficient photocatalytic activity of g-C3N4/Ag3PO4 hybrid photocatalysts through Z-scheme photocatalytic mechanism under visible light. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 53, 8018–8025 (2014).

Pany, S. & Parida, K. M. A facile in situ approach to fabricate N,S-TiO2/g-C3N4 nanocomposite with excellent activit for visible lighe induced water splitting for hydrogen evolution. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 17, 8070–8077 (2015).

Nayak, S. & Parida, K. M. Deciphering Z-scheme charge transfer dynamics in heterostructure NiFe-LDH/N-rGO/g-C3N4 nanocomposite for photocatalytic pollutant removal and water splitting reactions. Sci. Rep. 9, 2458 (2019).

Cai, J. S. et al. Crafting mussel-inspired metal nanoparticle-decorated ultrathin graphitic carbon nitride for the degradation of chemical pollutants and production of chemical resources. Adv. Mater. 31, 1806314 (2019).

Zheng, Y., Lin, L., Wang, B. & Wang, X. Graphitic carbon nitride polymers toward sustainable photoredox catalysis. Angew. Chem. Int. Edit. 54, 12868–12884 (2015).

Wang, Y., Wang, X. & Antonietti, M. Polymeric graphitic carbon nitride as a heterogeneous organocatalyst: from photochemistry to multipurpose catalysis to sustainable chemistry. Angew. Chem. Int. Edit. 51, 68–89 (2012).

Wang, X. et al. A metal-fee polymeric photocatalyst for hydrogen production from water under visible light. Nat. Mater. 8, 76–80 (2009).

Zhang, J., Zhang, M., Sun, R. Q. & Wang, X. A facile band alignment of polymeric carbon nitride semiconductors to sonstruct isotype heterojunctions. Angew. Chem. Int. Edit. 51, 10145–10149 (2012).

Yan, S. C., Li, Z. S. & Zou, Z. G. Photodegration performance of g-C3N4 fabricated by directly heatin melamine. Langmuir 25, 10397–10401 (2009).

Hong, J., Xia, X., Wang, Y. & Xu, R. Mesoporous carbon nitride with in situ sulfur doping for enhanced photocatalytic hydrogen evolution from water under visible light. J. Mater. Chem. 22, 15006–151012 (2012).

Dong, F. et al. Efficient synthesis of polymeric g-C3N4 layered materials as novel efficient visible light driven photocatalysts. J. Mater. Chem. 21, 15171–15174 (2011).

Fang., X. et al. Single Pt atoms confined into a metal-organic framework for efficient photocatalysis. Adv. Mater. 30, 1705112 (2018).

Xiong, T., Cen, W., Zhang, Y. & Dong, F. Bridging the g-C3N4 interlayers for enhanced photocatalysis. ACS Catal. 6, 2462–2472 (2016).

Parveen, N., Ansari, M. O., Ansari, S. A. & Cho, M. H. Simultaneous sulfur doping and exfoliation of graphene from rgaphite using an electrochemical method for supercapacitor electrode materials. J. Mater. Chem. A. 4, 233–240 (2016).

Cheng, F., Yin, H. & Xiang, Q. Low-temerature solid-state preparation of ternary CdS/g-C3N4/CuS nanocomposites for enhanced visible-light photocatalyti H2-production activity. Appl. Surf. Sci. 391, 432–439 (2017).

Shinde, S. L. et al. Enhanced solar light absorption and photoelectrochemical conversion using TiN nanoparticle-incorporated C3N4-C dot sheets. ACS Appl. Mater. Inter. 10, 2460–2468 (2018).

Xiang, Q., Yu, J. & Jaroniec, M. Preparation and enhanced visible-light photocatalytic H2-production activity of graphene/C3N4 composites. J. Phys. Chem. C 115, 7355–7363 (2011).

Fu, J., Bie, C., Cheng, B., Jiang, C. & Yu, J. Hollow CoSx polyhedrons act as high-efficiency cocatalyst for enhancing the photocatalytic hydrogen generation of g-C3N4. ACS Sustain. Chem. Engin. 6, 2767–2779 (2018).

Zhang, G., Lan, Z. A., Lin, L., Lin, S. & Wang, X. Overall water splitting by Pt-g-C3N4 photocatalysts without using sacrificial agents. Chem. Sci. 7, 3062–3066 (2016).

Chai, B., Peng, T., Mao, J., Li, K. & Zan, L. Graphitic carbon nitride (g-C3N4)-Pt-TiO2 nanocomposite as an efficient photocatalyst for hydrogen production under visible light irradiation. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 14, 16745–16752 (2012).

Linic, S., Christopher, P. & Ingram, D. B. Plasmonic-metal nanostructures for efficient conversion of solar to chemical energy. Nat. Mater. 10, 911–921 (2011).

An, C. et al. Plamonic silver incorporated silver halides for efficient photocatalysis. J. Mater. Chem. A. 4, 4336–4352 (2016).

Ong., W.-J., Putri, L. K., Tan, L.-L., Chai, S.-P. & Yong, S.-T. Heterostructured AgX/g-C3N4 (X=Cl and Br) nanocomposites via a sonication-assisted deposition-precipitation approach: emerging fole of halide ions in the synergistic photocatalytic reduction of carbon dioxide. Appl. Catal. B-Environ. 180, 530–543 (2016).

Ding, K., Yu, D., Wang, W., Gao, P. & Liu, B. Fabrication of multiple hierarchical heterojuction Ag@AgBr/BiPO4/r-GO with enhanced visible-light-driven photocatalytic activities towards dye degradation. Appl. Surf. Sci. 445, 39–49 (2018).

An, C., Wang, J., Liu, J., Wang, S. & Sun, Y. Hollow AgI:Ag nanoframes as solar photocatalysts for hydrogen generation from water reduction. ChemSusChem. 6, 1931–1937 (2013).

Liang, Y., Lin, S., Liu, L., Hu, J. & Cui, W. Oil-water self-assembled Ag@AgCl QDs sensitized Bi2WO6:enhanced photocatalytic degradation under visible light irradiation. Appl. Catal. B-Environ. 164, 192–203 (2015).

Wang, P. et al. Ag@AgCl: a highly efficient and stable photocatalyst active under visible light. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 47, 7931–7933 (2008).

Yu, J. G., Dai, G. P. & Huang, B. B. Fabrication and characterization of visible-light-driven plasmonic photocatalyst Ag/AgCl/TiO2 nanotube arrays. J. Phys. Chem. C 113, 16394–16401 (2009).

Feng, Z. Z., Yu, J. G., Sun, D. P. & Wang., T. H. Visible-light-driven photocatalysts Ag/AgCl dispersed on mesoporous Al2O3 with enhanced photocatalytic performance. J. Colloid Interf. Sci. 480, 184–190 (2016).

Jiang, J., Li, H. & Zhang, L. New insight into dalight photocatalysis of AgBr@Ag: synergisitc effect between semiconductor photocatalysis and plasmonic photocatalysis. Chem.-Eur. J. 18, 6360–6369 (2012).

Kang, M. G., Xu, T., Park, H. J., Luo, X. & Guo, L. J. Efficiency enhancement of organic solar cells using transparent plasmonic Ag nanowire electrodes. Adv. Mater. 22, 4378–4383 (2010).

Block, T., Tegenkamp, C., Baringhaus, J., Pfnür, H. & Inaoka, T. Plasmons in Pb nanowire arrays on Si(557): between one and two dimensions. Phys. Rev. B. 84, 205402 (2011).

Lou, Z., Gu, Q., Liao, Y., Yu, S. & Xue, C. Promoting Pd-catalyzed Suzuki coupling reactions throught near-infrared plasmon excitaiton of WO3-x nanowires. Appl. Catal. B-Environ. 184, 258–263 (2016).

Dhonde, M., Sahu, K., Murty, V. V. S., Nemala, S. S. & Bhargava, P. Surface plasmon resonance effect of Cu nanoparticles in a dye sensitized solar cell. Electrochim. Acta 249, 89–95 (2017).

Feng, Y., Shen, J., Cai, Q., Yang, H. & Shen, Q. The preparation and properties of a g-C3N4/AgBr nanocomposite photocatalyst based on protonation pretreatment. New J. Chem. 39, 1132–1138 (2015).

Yang, Y. X. et al. Frabrication of Z-scheme plasmonic photocatalyst Ag@AgBr/g-C3N4 with enhanced visible-light photocatalytic activity. J. Hazard. Mater. 271, 150–159 (2014).

Xu, Y. et al. A plasmonic photocatalyst of Ag/AgBr nanoparticles coupled with g-C3N4 with enhanced visible-light photocatalutic abilitu. Colloid Surface A. 436, 474–483 (2013).

Thomas, A. et al. Graphitic carbon nitride materials: variation of structure and morphology and their use as metal-free catalysts. J. Mater. Chem. 18, 4893–4908 (2008).

Wang, P., Huang, B., Dai, Y. & Whangbo, M. H. Plasmonic photocatlysts: harvesting visible light with noble metal nanoparticles. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 14, 9813–9825 (2012).

Li, X. K. & Ye, J. H. Photocatalytic degradation of rhodamine B over Pb3Nb4O13 fumed SiO2 composite under visible light irradiation. J. Phys. Chem. C. 111, 13109–13116 (2007).

Di paola, A., García-López, E., Marcì, G. & Palmisano, L. A survey of photocatalytic materials for environmental remediation. J. Hazard. Mater. 211-212, 3–29 (2012).

Samanta, S., Martha, S. & Parida, K. Facile synthesis of Au/g-C3N4 nanocomposites: an inorganic/organic hybrid plasmonic photocatalyst with enhanced hydrogen gas evolution under visible-light irradiation. ChemCatChem. 6, 1453–1462 (2014).

Wang, H. et al. Facile synthesis of AgBr nanoplated with exposed {111} facets and enhanced photocatalytic properties. Chem. Commun. 48, 275–277 (2012).

Nayak, S., Mohapatra, L. & Parida, K. Visible light-driven novel g-C3N4/NiFe-LDH composite photocatalyst with enhanced photocatalytic activity towards water oxidation and reduction reaction. J. Mater. Chem. A. 3, 18622–18635 (2015).

Xu, X., Liu, G., Randorn, C. & Irvine, J. T. S. g-C3N4 coated SrTiO3 as an efficient photocatalyst for H2 production in aqueous solution under visible light irradiation. Int. J. Hydrogen Energ. 36, 13501–13507 (2011).

He, F. et al. Facile approach to synthesize g-PAN/g-C3N4 composites with enhanced photocatalytic H2 evolution activity. ACS Appl. Mater. Inter. 6, 7171–7179 (2014).

Tian, N. et al. In situ co-pyrolysis fabrication of CeO2/g-C3N4 n-n type heterojunction for synchronously promoting photo-induced oxidation and reduction properties. J. Mater. Chem. A 3, 17120–17129 (2015).

Kang, H. W., Lim, S. N., Song, D. & Park, S. B. Organic-inorganic composite of g-C3N4-SrTiO3: Rh photocatalyst for improved H2 evolution under visible light irradiation. Int. J. Hydrogen Energ. 37, 11602–11610 (2012).

Mousavi, M. & Habibi-Yangjeh, A. Magnetically separable ternary g-C3N4/Fe3O4/BiOI nanocomposites: novel visible-light-driven photocatalyst based on graphitic carbon nitride. J. Colloid Interf. Sci. 465, 83–92 (2016).

Yu, J., Wang, S., low, J. & Xiao, W. Enhanced photocatalytic performance of direct Z-scheme g-C3N4-TiO2 photocatalysts for the decomposition of formaldehyde in air. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 15, 16883–16890 (2013).

Ge, L., han, C. & liu, J. Novel visible light-induced g-C3N4/Bi2WO6 composite photocatalysts for efficiency degradation of methyl orange. Appl. Catal. B-Environ. 108–109, 100–107 (2011).

Catchpole, K. R. & Polman, A. Design principles for particle plasmon enhanced solar cells. Appl. Phys. Lett. 93, 191113 (2008).

Gomathi Devi, L. & Kavitha, R. A review on plasmonic metal TiO2 composite for generation, trapping, storing and dynamic vectorial transfer of photogenerated electrons across the Schottky junction in a photocatalytic system. Appl. Surf. Sci. 360, 601–622 (2016).

Kavil, J., Anjana, P. M., Periyat, P. & Rakhi, R. B. One-pot synthesis of g-C3N4/MnO2 and g-C3N4/SnO2 hybrid nanocomposites for supercapacitor applications. Sustain. Energ. Fuels. 2, 2244–2251 (2018).

Ou, H., Yang, P., Lin, L., Anpo, M. & Wang, X. Carbon nitride aerogels for the photoredox conversion of water. Angew. Chem. Int. Edit. 56, 10905–10910 (2017).

Fang, Y., Li, X. & Wang, X. Phosphorylation of polymeric carbon nitride photoanodes with increased surface valence electrons for solar water splitting. ChemSusChem. 12, 2605–2608 (2019).

Ansari, S. A. & Cho, M. H. Growth of three-dimensional flower-like SnS2 ont g-C3N4 sheets as an efficient visible-light photocatalyst, photoelectrode, and electrochemical supercapacitance material. Sustain. Energ. Fuels. 1, 510–519 (2017).

Yang, P., Wang, R., Zhou, M. & Wang, X. Photochemical construction of carbonitride structures for red-light redox catalysis. Angew. Chem. Int. Edit. 57, 8674–8677 (2018).

Jiang, J., Zhang, X., Sun, P. & Zhang, L. ZnO/BiOI heterostructures: photoinduced charge-transfer property and ehanced visible-light photocatalytic activity. J. Phys. Chem. C 115, 20555–20564 (2011).

McFarland, E. W. & Tang, J. A photovoltaic device structure based on internal electron emission. Nature. 421, 616–618 (2003).

Xu, H. et al. Novel vislble-light-driven AgX/graphite-like C3N4 (X=Br, I) hybrid materials with synergistic photocatalytic activity. Appl. Catal. B-Environ. 129, 182–193 (2013).

Rycenga, M. et al. Controlling the synthesis and assembly of silver nanostructures for plasmonc applications. Chem. Rev. 111, 3669–3712 (2011).

Zhou, X. F., Hu, C., Hu, X. X., Peng, T. W. & Ou, J. H. Plasmon-assisted degradation of toxic pollutants with Ag-AgBr Al2O3 under visible-light irradiation. J. Phys. Chem. C 114, 2746–2750 (2010).

Cheng, H. et al. In situ ion exchange synthesis of the novel Ag/AgBr/BiOBr hybrid with highly efficient decontamination of pollutants. Chem. Commun. 47, 7054–7056 (2011).

Xu, Y.-S. & Zhang., W.-D. Ag/AgBr-grafted graphite-like carbon nitride with enhanced plasmonic photocatalytic activity under visible light. ChemCatChem. 5, 2343–2351 (2013).

Choi, M., Shin, K. H. & Jang, J. Plasmonic photocatalytic system using silver chloride/silver nanostructures under visible light. J. Colloid Interf. Sci. 341, 83–87 (2010).

Hong, J. D., Zhang, W., Wang, Y. B., Zhou, T. H. & Xu, R. Photocatalytic reduction of carbon dioxide over self-assembled carbon nitride and layered double hydroxide: the role of carbon dioxide enrichment. ChemCatChem. 6, 2315–2321 (2014).

Cao, J., Zhao, Y., Lin, H., Xu, B. & Chen, S. Ag/AgBr/g-C3N4: a highly efficient and stable composite photocatalyst for degradation of organic xontaminats under visible light. Mater. Res. Bell. 48, 3873–3880 (2013).

Che, Y. P. et al. Bio-inspired Z-scheme g-C3N4/Ag2CrO4 for efficient visible-light photocatalytic hydrogen generation. Sci. Rep. 8, 16504 (2018).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the International Science and Technology Cooperation Program of China (Grant Number 2014DFA52820); the National Key Research and Development Program of China (Grant Number 2017YFA0206902); and the National Basic Research Program (Grant Number 2012CB720904).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.C. and J.Z. supervised the project. Y.C. designed and carried out all experiments. B.L. helped with the experiments in electrochemical test and SEM measurements. Q.L., K.W. and Z.L. helped with the analysis of experimental results. Y.C. and B.L. drew the Fig. 1. Y.C. wrote the manuscript with important input from all authors. All authors have given approval to the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Che, Y., Liu, Q., Lu, B. et al. Plasmonic ternary hybrid photocatalyst based on polymeric g-C3N4 towards visible light hydrogen generation. Sci Rep 10, 721 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-57493-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-57493-x

This article is cited by

-

Fabricating a 3D floating porous PDMS − Ag/AgBr decorated g-C3N4 nanocomposite sponge as a re-usable visible light photocatalyst

Scientific Reports (2024)

-

Preparation of high-crystalline and non-metal modified g-C3N4 for improving ultrasound-accelerated white-LED-light-driven photocatalytic performances

Scientific Reports (2023)

-

Construction of a ternary g-C3N4/MoS2/MWCNTs nanocomposite for the enhanced photocatalytic performance against organic dye

Applied Nanoscience (2023)

-

Localized Surface Plasmonic Properties of Au and Ag Nanoparticles for Sensors: a Review

Plasmonics (2021)

-

Green synthesis of Ag NPs on magnetic polyallylamine decorated g-C3N4 by Heracleum persicum extract: efficient catalyst for reduction of dyes

Scientific Reports (2020)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.