Abstract

Monitoring seismic activity in the north Korean Peninsula (NKP) is important not only for understanding the characteristics of tectonic earthquakes but also for monitoring anthropogenic seismic events. To more effectively investigate seismic properties, reliable seismic velocity models are essential. However, the seismic velocity structures of the region have not been well constrained due to a lack of available seismic data. This study presents 1-D velocity models for both the inland and offshore (western East Sea) of the NKP. We constrained the models based on the results of a Bayesian inversion process using Rayleigh wave dispersion data, which were measured from ambient noise cross-correlations between stations in the southern Korean Peninsula and northeast China. The proposed models were evaluated by performing full moment tensor inversion for the 2013 Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK) nuclear test. Using the composite model consisting of both inland and offshore models resulted in consistently higher goodness of fit to observed waveforms than previous models. This indicates that seismic monitoring can be improved by using the proposed models, which resolve propagation effects along different paths in the NKP region.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

A reliable seismic velocity model is essential for monitoring and analyzing seismic activity and associate hazards. In addition, a well-determined seismic velocity model provides basic information for understanding the tectonic process of a region. However, seismic velocity structures in the northern Korean Peninsula (NKP) region in northeast Asia are not well studied due to a lack of available seismic networks. In contrast, dense seismic networks have been installed in the rest of northeast Asia, including northeast China, the southern Korean Peninsula (SKP), and the Japanese islands, and seismic velocity structures are therefore extensively mapped in these regions (e.g., Zheng et al. 2011; Wei et al. 2012; Witek et al. 2014; Shen et al. 2016; Kim et al. 2016b). In particular, one-dimensional (1-D) structures of the SKP have been estimated from studies using receiver functions and seismic waveform data (Chang and Baag 2005; Chang and Baag 2006; Lee and Baag 2008; Han et al. 2010; Kim et al. 2011; Kim et al. 2016a). Studies of the NKP region (e.g., Shin and Baag 2000; Ford et al. 2010) have relied on approximate velocity structures based on the SKP or global averages.

Despite relatively low seismicity, monitoring of seismic activity in the NKP region is particularly important. The largest instrumental earthquake (Mw 6.2) in the Korean Peninsula occurred near Pyongyang in North Korea, where more historical records of significant earthquakes are found (Kang and Jun 2011; Kyung et al. 2016). In addition, six nuclear explosion tests have been conducted since 2006 by the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK) government, generating the need for effective monitoring and detection of future potential activity (Hong and Rhie 2009; Barth 2014; Cesca et al. 2017).

However, complexities along propagation paths between the NKP and surrounding regions with dense instrumentation may thwart high-precision analysis for seismic sources and structures in the NKP. Seismic waves from events in the western NKP predominantly propagate through inland areas to seismic networks in the SKP (Fig. 1). On the other hand, offshore areas (the East Sea or Japan Sea) are included in the propagation paths from seismic events on the eastern coast of the NKP to stations in the SKP. According to studies on the crustal and upper mantle structure of northeast Asia (Tamaki 1988; Zheng et al. 2011; Lee et al. 2015), there is a significant difference in Moho depth along the margin of the Korean Peninsula, where crustal thinning due to opening of the East Sea has been suggested (Tamaki 1988; Yoon et al. 2014). In addition, velocity changes between the Korean Peninsula and East Sea have been reported in previous studies (e.g., Zheng et al. 2011; Witek et al. 2014; Kim et al. 2016b) and research into wave propagation across the continental margin has indicated strong effects of such marginal changes in crustal structure (Hong et al. 2008; Ford et al. 2009; Furumura et al. 2014).

a Location of Korea Meteorological Administration (KMA) and Korea Institute of Geoscience and Mineral Resources (KIGAM) stations (red triangles) and the NECESSArray (green triangles), as well as all possible 450 ray paths (gray blue lines). b Calculated cross-correlation section for ZZ cross-correlations with application of a 10–30-s band-pass filter

In regions with low seismicity or a lack of instrumentation, such as the NKP region, cross-correlation of seismic ambient noise can be utilized to obtain Green’s functions between station pairs (Shapiro et al. 2005; Bensen et al. 2007). The method is widely used for investigating velocity structures of the crust and upper mantle because it is effective for obtaining shorter period data of crustal depth than earthquake data (e.g., Bensen et al. 2007; Kang and Shin 2006; Choi et al. 2009; Pawlak et al. 2011; Shen et al. 2016; Kim et al. 2016b). In this study, we developed 1-D velocity models for the NKP region using Rayleigh wave dispersion data obtained from ambient noise cross-correlations between permanent network stations in SKP and a temporary network in northeast China (Northeast China Extended Seismic Array, NECESSArray). Two different models were presented to account for different propagation paths along the inland and offshore regions of the Korean Peninsula. The reliability of the estimated 1-D models was verified by calculating full model tensor solutions for the 2013 North Korea explosion nuclear test.

2 Data and methods

2.1 Data and processing

To obtain Rayleigh wave group and phase velocities, we used the vertical component of broadband continuous waveforms. Data were recorded at ten stations from KIGAM (Korea Institute of Geoscience And Mineral Resources) and KMA (Korea Meteorological Administration) installed in the northern part of SKP (above 36° N), and 45 stations from NECESSArray in the southern part of northeast China (below 45° N) from January 2010 to December 2011 (Fig. 1). For verification of the resulting models using moment tensor inversions, we used 2013 North Korea nuclear explosion test records for six broadband seismic stations in SKP and northeast China (Fig. 2).

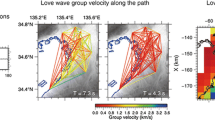

To construct the 1-D velocity model, we measured group and phase velocity dispersion data of the fundamental mode of Rayleigh waves using Green’s function waveforms obtained from ambient noise cross-correlation. Data preprocessing is similar to that of previous studies (e.g., Bensen et al. 2007; Lee et al. 2015). Instrument response, mean, and trend were removed from the vertical component continuous waveforms, which were divided into 1-day segments. Then, a band-pass filter between 0.01 and 0.45 Hz was applied. To reduce the effects of transient signals with large amplitudes, e.g. earthquakes, one-bit normalization was performed in the time domain. For cross-correlation functions of all possible pairs, a spectral whitening procedure was applied by dividing a 40-point moving average in the frequency domain. The distribution of stations generates 450 inter-station paths along the NKP mainland, East Sea, and Yellow Sea (Fig. 1). Signals with velocities of 3 to 4 km/s, corresponding to fundamental mode Rayleigh waves, were clearly observed in the cross-correlogram sections as a function of time and inter-station distance (Fig. 1). Potential interference of other signals from consistent noise sources such as the Aso volcano (e.g., Zheng et al. 2011; Lee et al. 2015) were not found in our data. Hence, we used an average of the positive and negative lag of the cross-correlogram to extract Green’s function for each station pair, which was used to measure group and phase velocity dispersion data by applying the multiple filter technique (Herrmann and Ammon 2004; Yao et al. 2006). In our procedure, dispersion curves were automatically measured based on the reference group and phase dispersion curves, which were obtained from a model of the SKP (Kim et al. 2011) and the AK135 model (Kennett et al. 1995) (Fig. 3).

Examples of estimated group and phase velocity dispersion curves between YKB-NE47 (red line in Fig. 1) and YKB-NE4A (blue line in Fig. 1). Background images are the FTAN diagrams for each curve. Ray paths exclusively sampling the northern Korean Peninsula show clear FTAN diagrams and well-estimated group and phase velocity dispersion points

To account for different features of wave propagation due to the complex marginal structures mentioned in section 1, we constructed two individual models for two distinct propagation paths. One model was for the propagation path through the inland of NKP (hereafter Mod_Land) and the other was for propagation paths through the East Sea region (hereafter Mod_Sea) (Fig. 4). Each model was constructed based on the 1-D model from Bayesian inversion using average dispersion curves (see section 2.2), which mainly sample each propagation path. The standard deviation of the dispersion curves was used as the observation error for the input parameter.

a, b 1-D shear velocity models obtained from Bayesian inversion using Rayleigh wave dispersion curves for both cases (Mod_Land, Mod_Sea). Top: all possible ray paths (gray lines) and used ray paths (blue line) for each model. Location of the Korea Meteorological Administration (KMA) and Korea Institute of Geoscience and Mineral Resources (KIGAM) stations (red triangles) and the NECESS array (green triangles). Middle: the posterior probability distribution (PPD) of the model parameters and the PPD of layer boundaries. Bottom: posterior distributions of predicted synthetic data with observed data

2.2 Bayesian inversion

The obtained surface wave dispersion data were inverted to estimate the 1-D shear wave velocity models for the corresponding path coverage regions. It is known that surface wave dispersion data have broader sensitivities to shear wave velocity structures than ballistic wave data such as body wave travel times (Ritzwoller et al. 2011; Obrebski et al. 2011). In this study, therefore, we utilized a Bayesian inversion method to account for potential non-uniqueness of solutions by estimating uncertainties, which were deduced from posterior probability distributions (PPD) of inversion parameters (Bodin et al. 2012; Kim et al. 2016a; Kim et al. 2016b). In particular, robust inversion uncertainties were calculated through a recently developed trans-dimensional and hierarchical technique (see Kim et al. 2016a and Kim et al. 2017 for further details). In this approach, probability distributions of the number of layers and the levels of data errors (variances) are sampled, through a Markov chain Monte Carlo method, together with those of other inversion parameters (e.g., layer thicknesses and velocities in each layer). Without applying regularization in the inversion process, this scheme systematically controls the balance between model complexity (i.e., the number of layers) and the degree of data fitting (i.e., the level of data errors). As a consequence, inversion results and corresponding uncertainties are less biased by arbitrary inversion settings. In addition, the approach is particularly useful in joint inversions as group and phase velocity dispersions are used together. The hyper-parameters for implementing the hierarchical scheme encompass the effect of different data sensitivities between different types (group and phase velocity) of data.

We used Rayleigh wave group and phase velocities from the average of the dispersion curves for each model (3~50 s-period for Mod_Land; 3~45 s-period for Mod_Sea). Bayesian inversions were performed for parameters consisting of Vs (2.0 ≤ Vs ≤ 5.5 km/s), Vp/Vs ratio (1.7 ≤ Vp/Vs ≤ 2.0), interface depth (up to 100 km), number of layers (between 2 and 30), and scaling factors for the level of data noise (between − 5.0 and 5.0). In each inversion, 2000 iterations were progressed and the previous 1000 samples were discarded to obtain converged posterior models. We simultaneously used 64 parallel chains to finally form a mean model from 1000 posterior sampled models. Figure 4 shows the prior ranges and estimated PPD for two different datasets. Based on the assumption that the PPD can be approximated as Gaussian shapes, we present inversion uncertainties with ± 2 standard deviations of the sampled models.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Models

The final two models are determined in the form of approximately two layers over a half-space model. The depth of layer boundaries is fixed manually based on peaks (the highest probability in a certain range of depths) of the PPD of the layer boundaries (Fig. 4). The velocity of each layer is determined by taking average values over each layer. Then, P velocity models are obtained by multiplying the determined S velocity models by the Vp/Vs ratio (Table 1). In Mod_Land, the estimated depth of the Moho is 30 km, which is 5 km deeper than in Mod_Sea (Figs. 4 and 5). Comparing Mod_Land and Mod_Sea, the depth of the uppermost crustal layer is similar (6.5~7 km) and the difference in velocity is only approximately 0.5%. For the second layer and half-space, velocities in Mod_Land are approximately 1.6% faster than that of Mod_Sea in both layers.

a 1-D velocity model of Mod_Land and that of previous studies. Dashed line represents 2σ of Mod_Land. b 1-D velocity model of Mod_Sea and that of previous studies. c Comparison of Mod_land and Mod_Sea. Shaded area dashed lines (light blue: Mod_Land; light red: Mod_Sea) represent 1, 2σ of Mod_Land and Mod_Sea. d Models used for moment tensor inversions

We qualitatively evaluate the obtained models by comparing with previous 1-D velocity models in the SKP. The first is a model determined through travel time data and waveform modeling of seismic phases of local earthquakes (Chang and Baag 2006; Mod_C&B). The second is a model that best fits the observation waveforms determined by a full-grid search (Kim et al. 2011; Mod_Kim). Mod_Land is generally similar to Mod_C&B and Mod_Kim, even taking into account the different number of layers (four) (Fig. 5). The Moho depth in Mod_Land developed using inland sampling data is similar (~ 30 km) to those in Mod_C&B and Mod_Kim and the velocity difference of each layer of Mod_C&B and Mod_Kim compared with Mod_Land is less than 4%, except for the lower crust part. It is known that the lower crust has been significantly modified by tectonic processes (e.g., Chough et al. 2000) in each region of the Korean Peninsula.

The influence of sampling paths through northeast China on Mod_Land is accounted for by the portion of inter-station paths that crosses the region. Considering previous studies on velocity structure in northeast Asia, the average crustal velocity in northeast China (~ 3.6 km/s) is not significantly different from that in the Korean peninsula (Zheng et al. 2011; Shen et al. 2016). In Songliao basin, the uppermost crustal velocity is slower than in the Korean peninsula by approximately 10% due to thick sediments. The Moho thickness is also relatively shallow; less than 30 km (Guo et al. 2015; Shen et al. 2016). However, the stations selected in this study are located at the boundary of the Songliao basin and the portion of paths through the basin does not exceed 20% of their total path-lengths. In addition, the standard deviation of the average dispersion curve for Mod_Land is small, even though it used paths across various regions (Fig. 4). Consequently, we conclude that paths are less influenced by the northeast China region and Mod_Land is sufficiently representative of NKP.

In Mod_Sea, the depth of the Moho is approximately 25 km, which is relatively shallow compared with Mod_Land and South models. Moreover, the velocity difference from Mod_Land is ~ 2% in each layer. This relatively small discrepancy indicates that, as previously suggested, the eastern margin of NKP is not completely oceanic crust but a rifted continental margin formed during expansion (Tamaki 1988; Yoon et al. 2014).

3.2 Model validation

To check the reliability of the constructed 1-D models, we perform full moment tensor (FMT) inversions for the 2013 DPRK nuclear experiment using the time domain moment tensor (TDMT) inversion method (Dreger and Helmberger 1993; Ford et al. 2009; Rhie and Kim 2010). The models are evaluated by measuring the goodness of fit between observed waveforms and those resulting from the FMT inversions. The hypocenter location and origin time information from a previous study (Barth 2014) is used. We select three-component waveform data from MDJ, DNH, NSN, BRD, CHJ, and SEO stations to use in the inversions, ensuring data conditions with good azimuthal coverage and high signal-to-noise ratio. For comparison, Mod_Kim and AK135 (Kennett et al. 1995) are also tested. Green’s function sets of three fundamental faults and a volumetric source (Saikia, 1994; Minson and Dreger 2008) are produced for each of the four models. Obtained waveforms of Green’s functions and observed data are band-pass filtered in the range of 10–50 s. Arbitrary time shifts are often applied in the TDMT process to empirically calibrate the inaccuracy of the used velocity model. In our model assessment, the time shift cannot be used to check model performance in terms of absolute times of phases as well as relative waveform similarities. For the goodness of fit, the variance reduction (VR) is calculated between synthetic and observation waveforms:

where Oi represents the ith data-point of the observation with n points, and Si represents the same but for synthetic data. Using data from the six stations, we perform TDMT inversions for all possible combinations (4096) of Green’s functions. For each station, four different sets of Green’s functions are generated using the four different models. Then, each inversion is performed using a composite set of Green’s functions allowing the same or different models between stations.

Figure 6 shows the results of the test, where the VR values for all combinations of Green’s functions range from 10.5 to 81.6% (Fig. 6a). The combination of Green’s functions from Mod_Land for MDJ, DNH, NSN, and BRD and from Mod_Sea for CHJ and SEO has the highest average VR (Fig. 6b). Interestingly, this result corresponds to the spatial coverage of dispersion data used to develop the models. Considering the propagation paths between the source and receivers, seismic waves mainly propagate through inland areas to MDJ, DNH, NSN, and BRD stations. On the other hand, CHJ and SEO stations record waveforms that spend much longer in the East Sea. Because Mod_Land and Mod_Sea are models developed for inland and East Sea regions, respectively, results of the FMT inversion tests indicate that the structural differences between paths through the inland and eastern margin of NKP influence the FMT results. These effects are accounted for by our estimated models.

a Hudson source type diagram for all possible combinations of each model. Red star represents the best result of this study. Blue, red, green, and gray squares represent source type using Mod_Land, Mod_Sea, Mod_Kim, and AK135, respectively. b The best moment tensor solution using Mod_Land (BRD, DNH, MDJ, NSN) and Mod_Sea (CHJ, SEO). c, d Moment tensor solutions of source type for green star (MDJ-Mod_Kim; DNH-Mod_Sea; NSN-Mod_Sea; BRD-Mod_Kim; SEO-Mod_AK135; CHJ-Mod_Kim) and orange star (MDJ-Sea_Kim; DNH-Mod_Sea; NSN-Mod_Land; BRD-Mod_Kim; SEO-Mod_Sea; CHJ-Mod_Sea). Observations are solid lines (black) and simulations are dashed (red)

The value of VR is 81.6% for the optimal combination of Green’s functions (Fig. 6b). This compares with VRs of inversions using single models of the Mod_Land (75.3%), Mod_Sea (77.1%), Mod_Kim (66.0%), and AK135 (52.6%), which show consistently lower VRs by 4.5 to 29.0% (Figs. 6 and 7). The FMT solution with the highest VR plotted on the Hudson source type diagram (Hudson et al. 1989) is similar to source types calculated in previous studies (Ford et al. 2009; Cesca et al. 2017). Interestingly, FMT solutions vary from opening to closing of cracks, even for those with reasonably high VRs (> 60%) (Fig. 6a). This indicates that the source type can be misjudged by inaccurate velocity models. Figures 6 c and d present inversion examples using different combinations of models, where solutions with high VRs (Fig. 6d; VR = 70.1%) can be the opposite (implosion), while an obtained solution with low VR (Fig. 6c; VR = 26.9%) has an extremely similar FMT solution. It is noted through this test that structural models used to calculate Green’s functions can play a major role in FMT calculation, particularly when the isotropic component is dominant, which makes the inversion unstable. The presented models may thus contribute to stabilizing FMT solutions for seismic events in NKP by using them for corresponding paths along continental regions around NKP and oceanic regions along the margin of NKP.

The FMT inversion results show that the Mod_Land and Mod_Sea models can improve the seismic monitoring of DPRK nuclear tests. Furthermore, this work indicates that the effect of wave propagations should be considered; developing more refined path-specific 1-D models or higher-dimensional models may further improve the FMT inversion results. In the future, radially anisotropic models can also be developed and tested because this study only assumes isotropic structures based on Rayleigh wave dispersion data.

4 Conclusion

In this study, we develop 1-D velocity models representing the inland and eastern margin of the NKP through the Bayesian inversion method using dispersion curves from the ambient noise records of surrounding networks (Figs. 4 and 5, Table 1). Although the velocity difference is small between Mod_Land and Mod_Sea models, Moho depths are clearly identified at 30 and 25 km, respectively. Mod_Land is similar to previous 1-D models (Mod_C&B and Mod_Kim) in the SKP region, which indicates that continental velocity structures in the Korean Peninsula are generally similar. Model verification using the FMT inversion for the 2013 DPRK nuclear test shows that a composite set of models consisting of Mod_Land and Mod_Sea for paths along the inland and eastern margin of NKP, respectively, provide a better solution in terms of the goodness of fit (VR) to waveforms than cases using either one of the models or with any possible combination of AK135 and Mod_Kim. Additionally, we confirm the reliability of the composite model, which may lead to improved FMT estimation for seismic events in NKP.

References

Barth A (2014) Significant release of shear energy of the North Korean nuclear test on February 12, 2013. J Seismol 18(3):605–615

Bensen GD, Ritzwoller MH, Barmin MP, Levshin AL, Lin F, Moschetti MP, Shapiro NM, Yang Y (2007) Processing seismic ambient noise data to obtain reliable broad-band surface wave dispersion measurements. Geophys J Int 169(3):1239–1260

Bodin T, Sambridge M, Tkalčić H, Arroucau P, Gallagher K, Rawlinson N, (2012) Transdimensional inversion of receiver functions and surface wave dispersion. Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth 117 (B2)

Cesca S, Heimann S, Kriegerowski M, Saul J, Dahm T (2017) Moment tensor inversion for nuclear explosions: what can we learn from the 6 January and 9 September 2016 nuclear tests, North Korea? Seismol Res Lett 88(2A):300–310

Chang SJ, Baag CE (2005) Crustal structure in southern Korea from joint analysis of teleseismic receiver functions and surface-wave dispersion. Bull Seismol Soc Am 95(4):1516–1534

Chang SJ, Baag CE (2006) Crustal structure in southern Korea from joint analysis of regional broadband waveforms and travel times. Bull Seismol Soc Am 96(3):856–870

Choi J, Kang TS, Baag CE (2009) Three-dimensional surface wave tomography for the upper crustal velocity structure of southern Korea using seismic noise correlations. Geosci J 13(4):423–432

Chough SK, Kwon ST, Ree JH, Choi DK (2000) Tectonic and sedimentary evolution of the Korean peninsula: a review and new view. Earth Sci Rev 52(1):175–235

Dreger DS, Helmberger DV (1993) Determination of source parameters at regional distances with three-component sparse network data. Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth 98(B5):8107-8125

Ford SR, Dreger DS, Walter WR (2009) Source analysis of the Memorial Day explosion, Kimchaek, North Korea. Geophysical Research Letters 36 (21)

Ford SR, Phillips WS, Walter WR, Pasyanos ME, Mayeda K, Dreger DS (2010) Attenuation tomography of the Yellow Sea/Korean Peninsula from coda-source normalized and direct Lg amplitudes. Pure Appl Geophys 167(10):1163–1170

Furumura T, Hong TK, Kennett BL (2014) Lg wave propagation in the area around Japan: observations and simulations. Prog Earth Planet Sci 1(1):10

Guo Z, Chen YJ, Ning J, Feng Y, Grand SP, Niu F, Kawakatsu H, Tanaka S, Obayashi M, Ni J (2015) High resolution 3-D crustal structure beneath NE China from joint inversion of ambient noise and receiver functions using NECESSArray data. Earth Planet Sci Lett 416:1–11

Han SI, Lee JM, Kang TS (2010) 1-D crustal velocity structure beneath broadband seismic stations in the Okcheon Fold Belt of Korea by receiver function analysis. Geosci J 14(1):57–66

Herrmann RB, Ammon CJ (2004) Surface waves, receiver functions and crustal structure. Computer programs in seismology: Version 3.30. Saint Louis University

Hong TK, Rhie J (2009) Regional Source Scaling of the 9 October 2006 Underground Nuclear Explosion in North Korea. Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America 99 (4):2523-2540

Hong TK, Baag CE, Choi H, Sheen DH (2008) Regional seismic observations of the 9 October 2006 underground nuclear explosion in North Korea and the influence of crustal structure on regional phases. J Geophys Res Solid Earth 113(B3)

Hudson JA, Pearce RG, Rogers RM (1989) Source type plot for inversion of the moment tensor. J Geophys Res Solid Earth 94(B1):765–774

Kang TS, Jun MS (2011) Some studies on the 1952 earthquake near Pyeongyang, North Korea, The 1st Annual Meeting of the Project of Seismic Hazard Assessment for the Next Generation Map: Strategic Japanese-Chinese-Korean Cooperative Program: Seismic Hazard Assessment for the Next Generation Map, November 25-30, 2011, Harbin, China, http://www.j-shis.bosai.go.jp/intl/cjk/1st_annual_meeting.html (last accessed on June 8, 2017)

Kang TS, Shin JS (2006) Surface-wave tomography from ambient seismic noise of accelerograph networks in southern Korea. Geophysical Research Letters 33 (17)

Kennett BLN, Engdahl ER, Buland R (1995) Constraints on seismic velocities in the Earth from traveltimes. Geophys J Int 122(1):108–124

Kim S, Rhie J, Kim G (2011) Forward waveform modelling procedure for 1-D crustal velocity structure and its application to the southern Korean Peninsula. Geophys J Int 185(1):453–468

Kim S, Dettmer J, Rhie J, Tkalčić H (2016a) Highly efficient Bayesian joint inversion for receiver-based data and its application to lithospheric structure beneath the southern Korean Peninsula. Geophys J Int 206(1):328–344

Kim S, Tkalčić H, Rhie J, Chen Y (2016b) Intraplate volcanism controlled by back-arc and continental structures in NE Asia inferred from transdimensional Bayesian ambient noise tomography. Geophys Res Lett 43:8390–8398

Kim S, Tkalčić H, Rhie J (2017) Seismic constraints on magma evolution beneath Mount Baekdu (Changbai) volcano from transdimensional Bayesian inversion of ambient noise data. J Geophys Res 122:5452–5473. https://doi.org/10.1002/2017JB014105

Kyung J, Kim M, Lee S, Kim J (2016) An analysis of probabilistic seismic hazard in the Korean Peninsula - probabilistic peak ground acceleration (PGA) in Korean. J Korean Earth Sci Soc 37(1):52–61

Lee W, Baag CE (2008) Local crustal structures of southern Korea from joint analysis of waveforms and travel times. Geosci J 12(4):419–428

Lee SJ, Rhie J, Kim S, Kang TS, Kim GB (2015) Ambient seismic noise tomography of the southern East Sea (Japan Sea) and the Korea Strait. Geosci J 19(4):709–720

Minson SE, Dreger DS (2008) Stable inversions for complete moment tensors. Geophys J Int 174(2):585–592

Obrebski M, Allen RM, Pollitz F, Hung SH (2011) Lithosphere–asthenosphere interaction beneath the western United States from the joint inversion of body-wave traveltimes and surface-wave phase velocities. Geophys J Int 185(2):1003–1021

Pawlak A, Eaton DW, Bastow ID, Kendall JM, Helffrich G, Wookey J, Snyder D (2011) Crustal structure beneath Hudson Bay from ambient-noise tomography: implications for basin formation. Geophys J Int 184(1):65–82

Rhie J, Kim S (2010) Regional moment tensor determination in the southern Korean Peninsula. Geosci J 14(4):329–333

Ritzwoller MH, Lin FC, Shen W (2011) Ambient noise tomography with a large seismic array. Compt Rendus Geosci 343(8):558–570

Saikia CK (1994) Modified frequency-wavenumber algorithm for regional seismograms using Filon’s quadrature: modelling of Lg waves in eastern North America. Geophys J Int 118(1):142–158

Shapiro NM, Campillo M, Stehly L, Ritzwoller MH (2005) High-resolution surface-wave tomography from ambient seismic noise. Science 307(5715):1615–1618

Shen W, Ritzwoller MH, Kang D, Kim Y, Lin FC, Ning J, Zhou L (2016) A seismic reference model for the crust and uppermost mantle beneath China from surface wave dispersion. Geophys J Int 206(2):954–979

Shin JS, Baag CE (2000) Moho depths in the border region between northern Korea and northeastern China from waveform analysis of teleseismic pMP and pP phases. Geosci J 4(4):313–320

Tamaki, K (1988) Geological structure of the Japan Sea and its tectonic implications. Bulletin of the Geological Survey of Japan, 39, 269–365

Wei W, Xu J, Zhao D, Shi Y (2012) East Asia mantle tomography: New insight into plate subduction and intraplate volcanism. J Asian Earth Sci 60:88–103

Witek M, van der Lee S, Kang TS (2014) Rayleigh wave group velocity distributions for East Asia using ambient seismic noise. Geophys Res Lett 41(22):8045–8052

Yao H, van Der Hilst RD, Maarten V (2006) Surface-wave array tomography in SE Tibet from ambient seismic noise and two-station analysis—I. Phase velocity maps. Geophys J Int 166(2):732–744

Yoon SH, Sohn YK, Chough SK (2014) Tectonic, sedimentary, and volcanic evolution of a back-arc basin in the East Sea (Sea of Japan). Mar Geol 352:70–88

Zheng Y, Shen W, Zhou L, Yang Y, Xie Z, Ritzwoller MH (2011) Crust and uppermost mantle beneath the North China Craton, northeastern China, and the Sea of Japan from ambient noise tomography. Journal of Geophysical Research 116 (B12)

Funding

This work was funded by the Korea Meteorological Administration under grant KMIPA2017-4010.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Lee, SJ., Rhie, J., Kim, S. et al. 1-D velocity model for the North Korean Peninsula from Rayleigh wave dispersion of ambient noise cross-correlations. J Seismol 24, 121–131 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10950-019-09891-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10950-019-09891-6