Abstract

The traditional focus on taxonomic diversity metrics for investigating species responses to habitat loss and fragmentation has limited our understanding of how biodiversity is impacted by habitat modification. This is particularly true for taxonomic groups such as bats which exhibit species-specific responses. Here, we investigate phylogenetic alpha and beta diversity of Neotropical bat assemblages across two environmental gradients, one in habitat quality and one in habitat amount. We surveyed bats in 39 sites located across a whole-ecosystem fragmentation experiment in the Brazilian Amazon, representing a gradient of habitat quality (interior-edge-matrix, hereafter IEM) in both continuous forest and forest fragments of different sizes (1, 10, and 100 ha; forest size gradient). For each habitat category, we quantified alpha and beta phylogenetic diversity, then used linear mixed-effects models and cluster analysis to explore how forest area and IEM gradient affect phylogenetic diversity. We found that the secondary forest matrix harboured significantly lower total evolutionary history compared to the fragment interiors, especially the matrix near the 1 ha fragments, containing bat assemblages with more closely related species. Forest fragments ≥ 10 ha had levels of phylogenetic richness similar to continuous forest, suggesting that large fragments retain considerable levels of evolutionary history. The edge and matrix adjacent to large fragments tend to have closely related lineages nonetheless, suggesting phylogenetic homogenization in these IEM gradient categories. Thus, despite the high mobility of bats, fragmentation still induces considerable levels of erosion of phylogenetic diversity, suggesting that the full amount of evolutionary history might not be able to persist in present-day human-modified landscapes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Humans have fundamentally changed the face of the Earth, with negative side-effects for biodiversity across all major biomes. Tropical forests are among the biomes impacted most heavily given the large footprint of pervasive land use changes which have resulted in widespread habitat loss and fragmentation (Austin et al. 2017; Barlow et al. 2018). These land use changes have detrimentally affected the richness, abundance, and composition of many tropical taxa (Alroy 2017), leading to a pattern of extensive defaunation, with cascading effects on ecosystem functioning (Young et al. 2016).

Idiosyncratic responses of species to fragmentation are ubiquitous, rendering assemblage-level inferences regarding fragmentation effects generally difficult (Ewers and Didham 2006; Fahrig 2017). This is mainly because the treatment of species as equal entities by neglecting their unique evolutionary history, functional roles in the ecosystem, and their association with each other within the community (Pellens and Grandcolas 2016), paints an incomplete picture of the effects of habitat fragmentation. Therefore, recent studies assessing the effect of habitat fragmentation on tropical taxa have started to incorporate evolutionary information using phylogenetic diversity metrics in addition to species richness (Frishkoff et al. 2014; Santos et al. 2014; Cisneros et al. 2015, 2016; Aguirre et al. 2016; Frank et al. 2017). By doing so, these studies were able to uncover patterns previously undetected by studies with a sole focus on the taxonomic dimension of biodiversity. For example, the decrease of distantly-related plant species in a fragmented landscape (Santos et al. 2014) suggests that habitat fragmentation impoverished evolutionary history of the taxa in question. Similar trends were also found in more mobile taxa such as birds and bats, which also showed that closely-related species tend to co-occur more often than expected by chance in various types of disturbed habitats (Riedinger et al. 2013; Frishkoff et al. 2014; Frank et al. 2017). This pattern, often referred to as phylogenetic clustering, indicates a strong effect of habitat filtering (Vamosi et al. 2009).

Phylogenetic clustering in fragmented landscapes, however, is not consistently supported by empirical evidence. Several studies have documented the tendency of phylogenetic overdispersion at the edge of fragmented forests (Santos et al. 2010; Peralta et al. 2015), suggesting that different types of habitat within a fragmented landscape differentially affect the evolutionary dimension of biodiversity. Gaining better insights into the extent to which phylogenetic diversity of assemblages is eroded as a result of habitat fragmentation therefore is critical to improve our general understanding of biodiversity persistence in human-modified landscapes.

Despite their mobility, bats (Chiroptera) are among the many animal groups that are demonstrably affected by habitat loss and fragmentation (Meyer et al. 2016; Alroy 2017). Notwithstanding increased research effort devoted over recent years to better understand how bats respond to habitat fragmentation, studies at the assemblage level, typically comparing species richness, diversity, and assemblage composition between forest fragments and continuous forest, show inconsistent results and highlight the need for more research focusing on the functional and phylogenetic biodiversity dimensions (Meyer et al. 2016). Bats are a good model group to study the effect of habitat fragmentation on phylogenetic diversity given their high species richness, functional diversity, and key roles in ecosystem functioning (Kunz et al. 2011). Studies employing a phylogenetic approach to investigate bat responses towards habitat disturbance (Cisneros et al. 2015; Frank et al. 2017; Presley et al. 2018) have been made possible by the availability of phylogenetic trees of all extant bat species (Jones et al. 2002, 2005; Shi and Rabosky 2015) that can be used to calculate phylogenetic diversity metrics.

Of the few studies that have investigated bat phylogenetic diversity in fragmented landscapes, none has assessed responses across the entire gradient in habitat quality typically encountered, formed by the interiors (I) and edges (E) of continuous forest and forest fragments, as well as the intervening matrix (M), or the IEM gradient (Rocha et al. 2017a). Explicit consideration of the full IEM gradient, however, is important to better understand the extent of habitat filtering that usually is regarded as the cause of phylogenetic clustering in disturbed habitats (Riedinger et al. 2013; Frank et al. 2017; Presley et al. 2018) as species persistence in fragmented landscapes may be differentially affected by this gradient in habitat quality (Ferreira et al. 2017). The observed phylogenetic richness and structure in each habitat that comprises the IEM gradient can give an indication about the amount of evolutionary history retained by the constituent habitat elements of a fragmented landscape (Cisneros et al. 2015). Moreover, exploring which habitats share similar evolutionary history or harbour lineages that are more closely related compared to other habitats may give insights into the evolution of habitat preferences (Graham and Fine 2008).

To elucidate how habitat fragmentation affects the evolutionary dimension of bat diversity, we investigated the changes in phylogenetic alpha and beta diversity of Amazonian bat assemblages across two environmental gradients, one in habitat quality (IEM gradient) and one in habitat amount (forest size: continuous forest; fragments of 1, 10 and 100 ha), in the experimentally fragmented landscape of the Biological Dynamics of Forest Fragments Project (BDFFP), the world’s largest and longest-running experimental study of habitat fragmentation (Haddad et al. 2015), investigating a total of 12 habitat categories (the IEM gradient of the continuous forest and forest fragments). We expected that differences in phylogenetic diversity between forest fragments of different size will depend on the habitat quality therein so that the interaction between IEM gradient and forest size (habitat amount) will affect both phylogenetic alpha and beta diversity. The assemblages in the secondary forest matrix should retain the least total evolutionary history due to selection of bat lineages that are best adapted to different levels of habitat quality (Rocha et al. 2018), followed by edges, while the interiors of continuous forest should harbour the most evolutionary history due to greatest resource availability (Ries and Sisk 2004). Accordingly, phylogenetic clustering should be strongest in the matrix surrounding the smallest forest fragments as habitat filtering would result in each habitat category harbouring lineages that have already been adapted to a specific set of habitat conditions (Farneda et al. 2015; Ferreira et al. 2017). These effects would result in low phylogenetic beta diversity among similar habitat categories as phylogenetic turnover would be low in assemblages containing similar types of lineages.

Methods

Study area

The BDFFP spans ~ 1000 km2 and is located approximately 80 km north of Manaus, Brazil (S2°30′, W60°; Fig. S1). The area contains different-sized forest fragments separated by 80–650 m from the surrounding continuous forest that serves as experimental control (Laurance et al. 2018). Following abandonment of the cattle pastures which initially surrounded the experimentally isolated fragments after their creation in the early 1980s, Vismia- and Cecropia-dominated secondary forest developed in the matrix (Mesquita et al. 2015). Fragment isolation was maintained by clearing and burning of a 100 m-wide strip of secondary forest around each of the forest fragments at intervals of ca. 10 years. Prior to this study, the most recent re-isolation occurred between 1999 and 2001 (Rocha et al. 2017b).

The forest at the BDFFP is a typical non-flooded forest of the Amazon basin (De Oliveira and Mori 1999), with approximately 280 species of trees (dbh > 10 cm) per hectare (Laurance et al. 2010). The area has a relatively flat topography (80–160 m), with nutrient-poor soils. Rainfall ranges from 1900 to 3500 mm annually, with a moderately strong dry season from June to October (Laurance et al. 2018).

Bat sampling

Bats were sampled with ground-level mist nets in eight primary forest fragments—three of 1 ha, three of 10 ha and two of 100 ha—and in nine control sites in three areas of continuous forest (Fig. S1). The eight forest fragments and three of the control sites were sampled in the interior, at the edges, and in the secondary forest matrix, whereas the remaining six control sites were sampled in their interior only, resulting in a total of 39 sites (Fig. S2). Distances between interior and edge sites of continuous forest and fragments were, respectively 1118 ± 488 and 245 ± 208 m (mean ± SD). Matrix sites were located ca. 100 m away from the border between primary and secondary forest. Edge sites were sampled with mist nets deployed in the contact zone between primary and secondary forest which allowed us to study edges as linear landscape features. In fragments, interior sites were placed in the centre whereas in continuous forest we placed sampling sites in areas previously sampled for different taxa. Selection of field sites was constrained by limitations associated with fieldwork in remote locations (we tried to use well marked trails, especially in continuous forest) and restrictions imposed by the BDFFP which has strict limitations regarding the opening of new trails in their experimental fragments. The placement of the mist nets was therefore limited to pre-existing trails which precluded a study design suitable to investigate edge penetration.

Each sampling site was visited eight times over a 2-year period (August 2011–June 2013). Bats were captured using 14 ground-level mist nets (12 × 2.5 m, 16 mm mesh, ECOTONE, Poland) in the interiors of forest fragments and continuous forest, and seven ground-level mist nets at the edge and matrix sites. The nets were exposed for 6 h after dusk and visited at intervals of ca. 20 min. Total sampling effort was 18,650 mist net hours ([1 mist-net hour (mnh) equals one 12-m net open for 1 h]) during which 4210 bats belonging to six families and 55 species were captured. We restricted our analyses to bats of the family Phyllostomidae, the only Neotropical bat family that can be adequately sampled with mist nets (Kalko 1998). Thus, 3494 captures from 43 species were included in our calculations of phylogenetic diversity.

Phylogenetic information

The phylogenetic information of phyllostomid species present at the BDFFP, hereafter referred to as the local phylogeny, was extracted from the most recent species-level phylogeny of bats (Shi and Rabosky 2015) using R package ‘picante’ (Kembel et al. 2010). We chose this particular tree as it covered more of the phyllostomid species that occur at the BDFFP compared to another frequently used bat phylogenetic tree published by Jones et al. (2002, 2005). The supertree was downloaded from TreeBASE and pruned to obtain the local phylogeny. The branch lengths of the local phylogeny represent the divergence time of the species in millions of years. As we used distance-based phylogenetic diversity metrics, the phylogenetic pairwise distance matrix was extracted from the local phylogeny using the ‘cophenetic.phylo()’ function from R package ‘ape’ (Paradis et al. 2004).

Species that occur in the study area but were not present in the pruned tree were substituted by their congeners, following Cisneros et al. (2016). Only for two out of 43 captured phyllostomid species was this the case, i.e. Artibeus gnomus and A. cinereus, which hence were both represented by their closest congener, A. glaucus (Redondo et al. 2008).

Measuring phylogenetic diversity

Alpha diversity

We explored variation in phylogenetic richness and structure within assemblages separately across the IEM gradient of 1, 10, and 100 ha fragments and continuous forest (CF) using Faith’s phylogenetic diversity (Faith 1992) and mean pairwise distance (Clarke and Warwick 1998; Webb 2000), hereafter referred to as PD and MPD, respectively. To account for different sampling effort across the 12 habitat categories, we performed individual-based rarefaction of the observed PD values of the different assemblages using the R package ‘BAT’ (Cardoso et al. 2015) by randomly (100×) sampling individuals from the regional pool; the sample size was the minimum abundance across all the 12 habitat categories, corresponding to 113 captures at the edges of the 1 ha fragments.

To assess the effect of phylogenetic information per se on PD, we eliminated any potential effect of species richness by calculating SESPD (standardized effect size of PD) under a ‘richness’ null model (Swenson 2014). Similarly, we quantified phylogenetic structure per se by calculating SESMPD (standardized effect size of MPD) using the tip-shuffling null model (Swenson 2014). However, as our local phylogeny consisted of closely related phyllostomids with quite a balanced topology, MPD could underestimate phylogenetic clustering in the terminal part of the phylogeny (Vamosi et al. 2009). We therefore also calculated the mean nearest taxon distance (MNTD) and computed SESMNTD using the tip-shuffling null model as it is more sensitive than MPD for detecting phylogenetic clustering in the terminal part of the local phylogeny (Tucker et al. 2017). Significant community structure can be inferred if the standardized effect size values lie above or below the 95% and 5% quantiles, respectively, of the null distribution. For SESMPD and SESMNTD, high quantiles (> 95%) indicate a phylogenetically over-dispersed assemblage whereas low quantiles (< 5%) indicate a phylogenetically clustered assemblage (Swenson 2014).

Beta diversity

To explore between-assemblage variation in phylogenetic richness and structure in relation to the habitat quality (IEM) and amount gradients, we calculated COMDIST and phylogenetic beta diversity (\({\text{P}}\upbeta_{\text{total}}\)), respectively. COMDIST is the mean pairwise phylogenetic distance (MPD) between species from different assemblages (Swenson 2011) which could help reveal which habitats along the gradient contain closely related lineages. To calculate COMDIST, we used R package ‘picante’ (Kembel et al. 2010). Phylogenetic beta diversity was partitioned into its richness (\({\text{P}}\upbeta_{\text{rich}}\)) and replacement (\({\text{P}}\upbeta_{\text{repl}}\)) components to capture, respectively, the difference in shared total branch lengths between assemblages and the uniqueness of each assemblage based on the evolutionary lineages present (Cardoso et al. 2014). To calculate \({\text{P}}\upbeta_{\text{total}}\) and its partitions, we used R package ‘BAT’ (Cardoso et al. 2015).

Phylogenetic alpha and beta diversity across the IEM and forest size gradient

Alpha diversity

We used linear mixed-effects models to assess how the IEM and forest size gradient affect the evolutionary dimension of biodiversity. For each metric of phylogenetic alpha diversity and its standardized effect size, we evaluated the multivariate relationships by incorporating an interaction term of the fixed effects IEM gradient (interior, edge, matrix) and forest size (CF, 100 ha, 10 ha, or 1 ha) as well as a random effect of site nested within location (i.e. sampling camp locations, see Fig. S2) using the ‘lme4’ package (Bates et al. 2015). If the full model was significant compared to the null model with only the intercept (P < 0.05), effects were further evaluated via multiple comparison tests using Tukey contrasts (adjusted P values reported) using the R package ‘multcomp’ (Hothorn et al. 2008). If the multivariate model was non-significant compared to the null model (P > 0.05), the full model was not further evaluated.

We note that adding the random effect did not improve the fit of the explanatory variables in the full model (see Table S1). Thus, we tested for spatial structure in the residuals of the significant models using Moran’s I (Moran 1950) calculated with the ‘spdep’ package (Bivand et al. 2008).

Beta diversity

To detect any implicit spatial structure in \({\text{P}}\upbeta_{\text{total}}\), \({\text{P}}\upbeta_{\text{rich}}\), \({\text{P}}\upbeta_{\text{repl}}\), and COMDIST, we visualized these metrics through UPGMA clustering (Borcard et al. 2011) using the ‘hclust’ function in R (R Core Team 2017). When applied to \({\text{P}}\upbeta_{\text{rich}}\), UPGMA will cluster assemblages with similar amount of phylogenetic richness whereas \({\text{P}}\upbeta_{\text{repl}}\) will cluster assemblages with similar lineages. For COMDIST, UPGMA will cluster closely related assemblages. A Mantel test (Mantel 1967) was conducted using the R package ‘vegan’ (Oksanen et al. 2017) to detect any linear (Pearson correlation) or non-linear (Spearman’s rank correlation) spatial structure in \({\text{P}}\upbeta_{\text{total}}\), \({\text{P}}\upbeta_{\text{rich}}\), \({\text{P}}\upbeta_{\text{repl}}\), and COMDIST.

Results

Comparison within assemblages: phylogenetic diversity is lowest in the smallest fragments

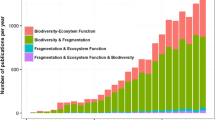

Rarefied PD showed a decreasing trend from continuous forest and fragment interiors to forest edges and matrix, with the matrix sites adjacent to the 1 ha fragments harbouring the lowest PD overall (Fig. 1). The likelihood ratio test supports the significance of the interaction between IEM gradient and forest size in explaining PD (L = 59.76, df = 11, P ≤ 0.001). The parameter estimates have a wide confidence interval so that we could not exclude the possibility of the effect of IEM gradient and forest size towards PD being much weaker or stronger (Table S2). However, multiple comparison tests showed that the decrease in PD from forest interior towards edge and matrix was significant in 1 ha fragments whereas in larger fragments the decrease was only significant in the edge (Table S3). Phylogenetic richness in 1 ha fragments was also considerably lower than in larger fragments across the entire IEM gradient (Table S3). When the effect of species richness on PD was accounted for (SESPD), the interaction term did not significantly improve model fit (L = 17.835, df = 11, P = 0.086). After subsequently dropping non-significant terms, we found that a univariate model incorporating the IEM gradient explained SESPD better than the full model (L = 7.341, df = 2, P = 0.026). The simulated null communities for PD further showed that SESPD values were considerably lower in the edges and matrix surrounding forest fragments compared to forest interior although smaller fragments do not exhibit considerably lower SESPD than larger fragments (Fig. 2a), further corroborating the strength of IEM gradient in explaining the phylogenetic richness of phyllostomid bats across the BDFFP.

Comparison of rarefied phylogenetic richness of bat assemblages across gradients of habitat quality (interior, edge, and matrix) and habitat amount (continuous forest, 100 ha fragment, 10 ha fragment and 1 ha fragment) at the Biological Dynamics of Forest Fragments Project, Brazil. The boxplots indicate the median, minimum, lower bound, upper bound, and maximum values of the repeated re-sampling of all pooled individuals, whereas the observed values of the total sum of branch lengths for all sites in each habitat category are overlaid on the boxplot as dots. Data were rarefied to the abundance level of the habitat category with the lowest number of captures (1 ha fragment edges, denoted by a line due to constituting the reference sample)

Standardized effect size (dots) of a Faith’s phylogenetic diversity (PD), b mean pairwise distance (MPD), and c mean nearest taxon distance (MNTD) along with 5% and 95% quantiles (dashed lines) of the simulated null communities (box and whisker plots). For SESMPD and SESMNTD, high quantiles (> 95%) indicate a phylogenetically over-dispersed assemblage whereas low quantiles (< 5%) indicate a phylogenetically clustered assemblage. In the box plots, values of observed PD, MPD, and MNTD overlaid on the simulated null communities are indicated by a black diamond

The pattern of phylogenetic structure captured by MPD was likely caused by the interaction between IEM gradient and forest size (L = 26.587, df = 11, P = 0.005), even when we standardized the effect of phylogenetic structure (L = 22.201, df = 11, P = 0.023). In line with our full model, the simulated null communities showed that SESMPD values were lower than expected in the interiors of 1 ha fragments, fragment edges, and the matrix around the larger (10 and 100 ha) fragments (Fig. 2b). The assemblages in the matrix surrounding 1 ha fragments, although not characterised as phylogenetically clustered based on its SESMPD (Fig. 2b), showed terminal clustering based on its significantly lower SESMNTD (Fig. 2c). Our data could not provide enough evidence to infer the difference in phylogenetic structure between habitat categories, however, multiple comparison tests showed that most pairwise differences among habitat categories were largely caused by chance (see Table S4 for MPD and Table S5 for SESMPD) except between 100 ha matrix and 10 ha interiors (P = 0.015 for MPD and P = 0.006 for SESMPD, Tables S4 and S5, respectively). According to the local phylogeny (Fig. S3), most lineages that reside within the matrix surrounding 100 ha fragments are different from those in the interiors of 10 ha fragments. The distinctiveness of these two habitat categories was also corroborated by the replacement component of phylogenetic beta diversity (\({\text{P}}\upbeta_{\text{repl}}\), Fig. 3c). The confidence interval was also relatively large for the parameter estimates of the models for MPD and SESMPD, indicating that our models were unreliable in predicting the phylogenetic structure in our study design (Table S2).

Our results were unlikely affected by spatial autocorrelation as global Moran’s I tests did not show any spatial dependence of the residuals of the fitted models (Table S6, all P > 0.05). The implicit spatial structure of sampling site nested within location also unlikely contributes to the pattern of phylogenetic diversity metrics, considering the low variance of the random effects (see Table S2).

Comparison between assemblages: no clear pattern of lineage replacement

Dendrograms based on the total evolutionary history shared between assemblages (Pβtotal, Pβrich, and Pβrepl; Fig. 3) were substantially different from the one based on relatedness between lineages within assemblages (COMDIST; Fig. 4). UPGMA clustering based on total phylogenetic beta diversity (Pβtotal) suggested that the interiors of continuous forest and forest fragments harbour similar amounts of phylogenetic richness, except for the 1 ha fragments (Fig. 3a), further confirming the phylogenetic erosion of 1 ha fragments. The similarity in total phylogenetic richness between the interiors of continuous forest and larger forest fragments (10 and 100 ha) was maintained after Pβtotal was partitioned into Pβrich and Pβrepl. For Pβrich, however, the interior sites of the larger fragments clustered together, unlike Pβtotal which grouped the interior of continuous forest closer together with that of 100 ha fragments (Fig. 3b). For Pβrepl, the interior sites were over-dispersed (Fig. 3c), suggesting that the difference in Pβtotal compared to Pβrich is caused by different lineages contained within the interiors. Although there was a significant relationship between geographic proximity and Pβtotal (Pearson’s Mantel statistic r = 0.134, P = 0.013, Table S7), the relationship did not hold when we partitioned Pβtotal into Pβrepl (Pearson’s Mantel statistic r = 0.031, P = 0.299, Table S7) and Pβrich (Pearson’s Mantel statistic r = 0.059, P = 0.138, Table S7).

UPGMA clustering of COMDIST revealed that the investigated assemblages were closely related and were not clustered according to either the same IEM gradient or the same forest size categories (Fig. 4). The position of the interior sites of 1 ha fragments distant from those of larger fragments and continuous forest, underscores the distinct composition of bat lineages in the assemblages of 1 ha fragments.

The distinct composition of bat lineages in the interior, edge, and matrix surrounding 1 ha fragments was further corroborated by the local phylogeny (Fig. S3). The interiors of 1 ha fragments contained different bat lineages compared to interior sites of the larger fragments and continuous forest, and these lineages were also present in the edge and matrix of 1 ha fragments (Fig. S3). The local phylogeny further showed that there was no clear pattern of lineage distribution at forest edges and in the matrix adjoining continuous forest and fragments whereas interiors contained diverse lineages. This pattern unlikely resulted from spatial effects as there was no significant relationship between COMDIST and geographic distance (Pearson’s Mantel statistic r = 0.055, P = 0.230, Table S7).

Discussion

Using metrics of phylogenetic alpha and beta diversity, we showed that bat assemblages in the BDFFP landscape exhibit both a decrease of phylogenetic richness in the matrix and edges of forest fragments compared to the interior of continuous forest and a phylogenetic homogenization in these categories of the IEM gradient, as the sites in matrix and edges contained closely related bat lineages. The two environmental gradients investigated in this study explained quite well the observed variation in total phylogenetic richness (PD), but only the IEM gradient accounted for the phylogenetic information independent from species richness (SESPD). Although the mean phylogenetic distance of bat assemblages (MPD) in different fragment sizes apparently varies across the habitat categories of the IEM gradient even when quantified by its standardized effect size (SESMPD), the two environmental gradients here investigated were unable to explain the differences in phylogenetic structure among the 12 habitat categories. In agreement with this, the cluster analysis of phylogenetic beta diversity metrics did not clearly group assemblages from the same category of habitat quality and amount together as a result of high phylogenetic turnover between these assemblages.

The erosion of phylogenetic richness in edge and matrix of forest fragments, especially in the smallest fragments (1 ha), showed that habitat fragmentation at the BDFFP does not only negatively affect bat taxonomic and functional diversity in those habitat categories (Farneda et al. 2015; Rocha et al. 2017a) but also the total evolutionary history preserved. Phylogenetic beta diversity further showed marked changes in phylogenetic richness and structure of 1 ha fragment interiors along with its similarity to their edges in terms of preserved evolutionary history (Fig. 3), suggesting that patterns of phylogenetic diversity are fundamentally driven by the pervasive negative edge effects that commonly plague fragments of this size (Santos et al. 2010; Laurance et al. 2018).

In accordance with other studies comparing phylogenetic richness between various human-modified habitats of different levels of forest/vegetation complexity (Riedinger et al. 2013; Frishkoff et al. 2014; Edwards et al. 2015, 2017; Frank et al. 2017; Martins et al. 2017; Ribeiro et al. 2017; Pereira et al. 2018), the observed decrease in total evolutionary history in a structurally less complex habitat such as the secondary forest matrix is not surprising. Through the use of SESMPD and SESMNTD, we further showed that the edges and matrix of forest fragments also experienced phylogenetic clustering, whereby the matrix of 1 ha fragments was characterized by especially closely related lineages. Matrix sites surrounding 1 ha fragments are impoverished with respect to lineages with long evolutionary history, e.g. Lampronycteris brachyotis and several Micronycteris species (Fig. S3), and contain lineages that are phylogenetically clustered in the terminal branches. These absent lineages were also rarely present in disturbed habitat (Medellín et al. 2000; Frank et al. 2017), and their traits were documented to be highly associated with forest cover and tree height (Farneda et al. 2015). As these insectivorous lineages did not change their main feeding habit along their course of evolutionary history, they will be more vulnerable to habitat fragmentation compared to their frugivorous relatives which evolved independently multiple times within the Phyllostomidae in a relatively recent time (Rojas et al. 2011) and hence are better preadapted to disturbed habitat (Medellín et al. 2000; Farneda et al. 2015).

Although sites in the interior, edges, and matrix of 1 ha fragments experienced a considerable reduction in phylogenetic richness and exhibited phylogenetic clustering, we found that the change of phylogenetic diversity in lower quality habitat did not consistently depend on habitat amount. Phylogenetic beta diversity metrics further corroborate the weak effect of the two environmental gradients on between-assemblage differences in phylogenetic richness and lineage composition as there was no clear-cut pattern with regard to the relatedness and phylogenetic richness of bat assemblages in relation to IEM and forest size gradients. This is potentially due to the influence of landscape-level attributes which encompass wider environmental gradients (Rocha et al. 2017a; Tinoco et al. 2018). The low structural contrast between secondary regrowth in the matrix and the forest interiors during the sampling period could also attenuate any strong phylogenetic structure of bat assemblages along the interior-edge-matrix gradient; Patrick and Stevens (2016) for instance found that environmental variables have a weaker effect upon phylogenetic structure when assemblages experience less harsh environmental conditions. Our measure of phylogenetic beta diversity also supports the unclear separation between different IEM gradient categories. Spatial autocorrelation in the case of total phylogenetic richness among habitat categories was unlikely an issue as the autocorrelation did not hold after we partitioned the phylogenetic beta diversity into its richness and replacement component.

The lack of a marked difference between the edge and matrix sites associated with the larger forest fragments and continuous forest possibly reflects a predominant effect of dispersal ability in the absence of contrasting environmental gradients (Moreno and Halffter 2001). Additionally, the abiotic filter that is responsible for phylogenetic clustering could possibly result from non-linear responses (Smith and Lundholm 2010; Stegen and Hurlbert 2011) that we were unable to detect using linear models. Stronger support for an effect of the IEM gradient in explaining phylogenetic structure may have been obtained if we had considered abundance-based metrics and quantitative variables such as seasonal temperature (Stevens and Gavilanez 2015) or elevation (Cisneros et al. 2014). Nonetheless, our findings still confirm our expectations that the low resource availability in the matrix selects for lineages that have traits favoured by the existing habitat filter (Farneda et al. 2015).

As our study system comprises a relatively modest gradient of forest structure (Rocha et al. 2017a), the presence of closely related bat lineages in the edge and matrix of small forest fragments could be attributed to selection towards traits determining competitiveness instead of the niche of species, particularly if the niche differences among bat lineages were not strongly related to their phylogeny (Mayfield and Levine 2010; Gerhold et al. 2015). Considering the strong sensitivity of several functional traits towards fragmentation (Farneda et al. 2015; Nuñez et al. 2019) we argue that phylogenetic clustering in habitat of low quality could lead to trait convergence to reduce competition asymmetry between closely-related species (Scheffer and van Nes 2006) and may further decrease the phylogenetic diversity of the assemblage. Thus, despite the ability of large forest fragments to retain amounts of total evolutionary history similar to the interior of continuous forest, the level of forest degradation at the edges and in the matrix still has a negative effect on the phylogenetic diversity of bats at the BDFFP.

We note that establishing the generality of our findings requires further studies as the experimentally controlled fragmented landscape of the BDFFP is a best-case scenario as levels of disturbance are reduced in relation to most real-world landscapes (Laurance et al. 2018). Additionally, forest fragments are surrounded by a soft matrix dominated by forest regrowth (Mesquita et al. 2015), and which is largely free from human disturbances which could interact additively or synergistically with fragmentation (Laurance et al. 2018). The matrix was dominated by tall secondary forest regrowth at the time of study (Rocha et al. 2017a), resulting in a rather homogenous makeup of the overall landscape which could promote random co-occurrence of bat lineages from our lineage pool (Morlon et al. 2011).

Landscape-scale studies are subject to the issue of pseudo-replication (Ramage et al. 2013) and our study at the BDFFP is no exception given that our sampling sites do not constitute true replicates of several independent fragmented landscapes. However, we believe our findings to be generalizable towards other landscapes with similar scale of habitat fragmentation. Our results regarding phylogenetic beta diversity showed that the two environmental gradients investigated were insufficient to detect meaningful trends in the pattern of phylogenetic diversity in our study system. Deciding which aspect of the environment actually matters for the taxa in question and on which ecological and evolutionary scale, however, remains a challenging part of such landscape-level studies.

Our study adds to a growing body of evidence suggesting biotic homogenization in human-modified landscapes is widespread not only with regard to the taxonomic facet of biodiversity but also its evolutionary dimension (La Sorte et al. 2018; Park and Razafindratsima 2019). Despite the aforementioned caveats, we showed fragmentation to result in the loss of species lineages and phylogenetic homogenization of assemblages in degraded edge and matrix habitats. This could further affect ecosystem stability as communities where species are evenly and distantly related to one another are more stable compared to communities where phylogenetic relationships are more clumped (Cadotte et al. 2012). The conservation of large forest fragments and the improvement of habitat quality thus should be prioritized in managing fragmented tropical forest landscapes to conserve species with longer evolutionary history.

References

Aguirre LF, Montaño-Centellas FA, Gavilanez MM, Stevens RD (2016) Taxonomic and phylogenetic determinants of functional composition of bolivian bat assemblages. PLoS ONE 11:e0158170. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0158170

Alroy J (2017) Effects of habitat disturbance on tropical forest biodiversity. Proc Natl Acad Sci 114:6056–6061. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1611855114

Austin KG, González-Roglich M, Schaffer-Smith D et al (2017) Trends in size of tropical deforestation events signal increasing dominance of industrial-scale drivers. Environ Res Lett 12:079601. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/aa7760

Barlow J, França F, Gardner TA et al (2018) The future of hyperdiverse tropical ecosystems. Nature 559:517. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-018-0301-1

Bates D, Mächler M, Bolker B, Walker S (2015) Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. J Stat Softw 67:1–48. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v067.i01

Bivand RS, Pebesma EJ, Gómez-Rubio V (2008) Applied spatial data analysis with R. Springer, New York

Borcard D, Gillet F, Legendre P (2011) Numerical ecology with R. Springer, New York

Cadotte MW, Dinnage R, Tilman D (2012) Phylogenetic diversity promotes ecosystem stability. Ecology 93:S223–S233

Cardoso P, Rigal F, Carvalho JC et al (2014) Partitioning taxon, phylogenetic and functional beta diversity into replacement and richness difference components. J Biogeogr 41:749–761. https://doi.org/10.1111/jbi.12239

Cardoso P, Rigal F, Carvalho JC (2015) BAT - Biodiversity Assessment Tools, an R package for the measurement and estimation of alpha and beta taxon, phylogenetic and functional diversity. Methods Ecol Evol 6:232–236. https://doi.org/10.1111/2041-210X.12310

Cisneros LM, Burgio KR, Dreiss LM et al (2014) Multiple dimensions of bat biodiversity along an extensive tropical elevational gradient. J Anim Ecol 83:1124–1136. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2656.12201

Cisneros LM, Fagan ME, Willig MR (2015) Effects of human-modified landscapes on taxonomic, functional and phylogenetic dimensions of bat biodiversity. Divers Distrib 21:523–533. https://doi.org/10.1111/ddi.12277

Cisneros LM, Fagan ME, Willig MR (2016) Environmental and spatial drivers of taxonomic, functional, and phylogenetic characteristics of bat communities in human-modified landscapes. PeerJ 4:e2551. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.2551

Clarke KR, Warwick RM (1998) A taxonomic distinctness index and its statistical properties. J Appl Ecol 35:523–531

De Oliveira AA, Mori SA (1999) A central Amazonian terra firme forest. I. High tree species richness on poor soils. Biodivers Conserv 8:1219–1244

Edwards DP, Gilroy JJ, Thomas GH et al (2015) Land-sparing agriculture best protects avian phylogenetic diversity. Curr Biol 25:2384–2391. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2015.07.063

Edwards DP, Massam MR, Haugaasen T, Gilroy JJ (2017) Tropical secondary forest regeneration conserves high levels of avian phylogenetic diversity. Biol Cons 209:432–439. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2017.03.006

Ewers RM, Didham RK (2006) Confounding factors in the detection of species responses to habitat fragmentation. Biol Rev 81:117. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1464793105006949

Fahrig L (2017) Ecological responses to habitat fragmentation per se. Annu Rev Ecol Evol Syst 48:1–23. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-ecolsys-110316-022612

Faith DP (1992) Conservation evaluation and phylogenetic diversity. Biol Cons 61:1–10

Farneda FZ, Rocha R, López-Baucells A et al (2015) Trait-related responses to habitat fragmentation in Amazonian bats. J Appl Ecol 52:1381–1391. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2664.12490

Ferreira DF, Rocha R, López-Baucells A et al (2017) Season-modulated responses of Neotropical bats to forest fragmentation. Ecol Evol 7:4059–4071. https://doi.org/10.1002/ece3.3005

Frank HK, Frishkoff LO, Mendenhall CD et al (2017) Phylogeny, traits, and biodiversity of a Neotropical bat assemblage: close relatives show similar responses to local deforestation. Am Nat 190:200–212. https://doi.org/10.1086/692534

Frishkoff LO, Karp DS, M’Gonigle LK et al (2014) Loss of avian phylogenetic diversity in Neotropical agricultural systems. Science 345:1343–1346

Gerhold P, Cahill JF, Winter M et al (2015) Phylogenetic patterns are not proxies of community assembly mechanisms (they are far better). Funct Ecol 29:600–614. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2435.12425

Graham CH, Fine PVA (2008) Phylogenetic beta diversity: linking ecological and evolutionary processes across space in time. Ecol Lett 11:1265–1277. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1461-0248.2008.01256.x

Haddad NM, Brudvig LA, Clobert J et al (2015) Habitat fragmentation and its lasting impact on Earth’s ecosystems. Sci Adv 1:e1500052–e1500052. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.1500052

Hothorn T, Bretz F, Westfall P (2008) Simultaneous inference in general parametric models. Biosciences 50:346–363

Jones KE, Purvis A, MacLarnon A et al (2002) A phylogenetic supertree of the bats (Mammalia: Chiroptera). Biol Rev 77:223–259

Jones KE, Bininda-Emonds ORP, Gittleman JL (2005) Bats, clocks, and rocks: diversification patterns in Chiroptera. Evolution 59:2243. https://doi.org/10.1554/04-635.1

Kalko EKV (1998) Organisation and diversity of tropical bat communities through space and time. Zoology 101:281–297

Kembel SW, Cowan PD, Helmus MR et al (2010) Picante: R tools for integrating phylogenies and ecology. Bioinformatics 26:1463–1464. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btq166

Kunz TH, Braun de Torrez E, Bauer D et al (2011) Ecosystem services provided by bats. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1223:1–38. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-6632.2011.06004.x

La Sorte FA, Lepczyk CA, Aronson MFJ et al (2018) The phylogenetic and functional diversity of regional breeding bird assemblages is reduced and constricted through urbanization. Divers Distrib 24:928–938. https://doi.org/10.1111/ddi.12738

Laurance SGW, Laurance WF, Andrade A et al (2010) Influence of soils and topography on Amazonian tree diversity: a landscape-scale study. J Veg Sci 21:96–106. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1654-1103.2009.01122.x

Laurance WF, Camargo JLC, Fearnside PM et al (2018) An Amazonian rainforest and its fragments as a laboratory of global change. Biol Rev 93:223–247. https://doi.org/10.1111/brv.12343

Mantel N (1967) The detection of disease clustering and a generalized regression approach. Cancer Res 27:209–220

Martins ACM, Willig MR, Presley SJ, Marinho-Filho J (2017) Effects of forest height and vertical complexity on abundance and biodiversity of bats in Amazonia. For Ecol Manag 391:427–435. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2017.02.039

Mesquita RCG, dos Massoca PES, Jakovac CC et al (2015) Amazon rain forest succession: stochasticity or land-use legacy? Bioscience 65:849–861. https://doi.org/10.1093/biosci/biv108

Mayfield MM, Levine JM (2010) Opposing effects of competitive exclusion on the phylogenetic structure of communities: phylogeny and coexistence. Ecol Lett 13:1085–1093. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1461-0248.2010.01509.x

Medellín RA, Equihua M, Amin MA (2000) Bat diversity and abundance as indicators of disturbance in Neotropical rainforests. Conserv Biol 14:10

Meyer CFJ, Struebig MJ, Willig MR (2016) Responses of tropical bats to habitat fragmentation, logging, and deforestation. In: Voigt CC, Kingston T (eds) Bats in the Anthropocene: conservation of bats in a changing world. Springer International Publishing, Cham, pp 63–103

Moran PAP (1950) Notes on continuous stochastic phenomena. Biometrika 37:17–23. https://doi.org/10.2307/2332142

Moreno CE, Halffter G (2001) Spatial and temporal analysis of α, β and γ diversities of bats in a fragmented landscape. Biodivers Conserv 10:367–382

Morlon H, Schwilk DW, Bryant JA et al (2011) Spatial patterns of phylogenetic diversity. Ecol Lett 14:141–149. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1461-0248.2010.01563.x

Nuñez SF, Baucells AL, Rocha R et al (2019) Echolocation and stratum preference: key trait correlates of vulnerability of insectivorous bats to tropical forest fragmentation. Front Ecol Evol. https://doi.org/10.3389/fevo.2019.00373

Oksanen J, Blanchet FG, Friendly M, et al (2017) Vegan: Community Ecology Package

Paradis E, Claude J, Strimmer K (2004) APE: analyses of phylogenetics and evolution in r language. Bioinformatics 20:289–290. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btg412

Park DS, Razafindratsima OH (2019) Anthropogenic threats can have cascading homogenizing effects on the phylogenetic and functional diversity of tropical ecosystems. Ecography 42:148–161. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecog.03825

Patrick LE, Stevens RD (2016) Phylogenetic community structure of North American desert bats: influence of environment at multiple spatial and taxonomic scales. J Anim Ecol 85:1118–1130. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2656.12529

Pellens R, Grandcolas P (2016) Phylogenetics and conservation biology: drawing a path into the diversity of life. In: Biodiversity conservation and phylogenetic systematics: preserving our evolutionary heritage in an extinction crisis. Berlin: Springer Open, pp 1–15

Peralta G, Frost CM, Didham RK et al (2015) Phylogenetic diversity and co-evolutionary signals among trophic levels change across a habitat edge. J Anim Ecol 84:364–372. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2656.12296

Pereira MJR, Fonseca C, Aguiar LMS (2018) Loss of multiple dimensions of bat diversity under land-use intensification in the Brazilian Cerrado. HYSTRIX 29:25–32. https://doi.org/10.4404/hystrix-00020-2017

Presley SJ, Cisneros LM, Higgins CL et al (2018) Phylogenetic and functional underdispersion in Neotropical phyllostomid bat communities. Biotropica 50:135–145. https://doi.org/10.1111/btp.12501

R Core Team (2017) R: a language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna

Ramage BS, Sheil D, Salim HM et al (2013) Pseudoreplication in tropical forests and the resulting effects on biodiversity conservation. Conserv Biol 27:364–372

Redondo RAF, Brina LPS, Silva RF et al (2008) Molecular systematics of the genus Artibeus (Chiroptera: Phyllostomidae). Mol Phylogenet Evol 49:44–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ympev.2008.07.001

Ribeiro J, Colli GR, Batista R, Soares A (2017) Landscape and local correlates with anuran taxonomic, functional and phylogenetic diversity in rice crops. Landscape Ecol 32:1599–1612. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10980-017-0525-8

Riedinger V, Müller J, Stadler J et al (2013) Assemblages of bats are phylogenetically clustered on a regional scale. Basic Appl Ecol 14:74–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.baae.2012.11.006

Ries L, Sisk TD (2004) A predictive model of edge effects. Ecology 85:2917–2926

Rocha R, López-Baucells A, Farneda FZ et al (2017a) Consequences of a large-scale fragmentation experiment for Neotropical bats: disentangling the relative importance of local and landscape-scale effects. Landscape Ecol 32:31–45. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10980-016-0425-3

Rocha R, Ovaskainen O, López-Baucells A et al (2017b) Design matters: an evaluation of the impact of small man-made forest clearings on tropical bats using a before-after-control-impact design. For Ecol Manag 401:8–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2017.06.053

Rocha R, Ovaskainen O, López-Baucells A et al (2018) Secondary forest regeneration benefits old-growth specialist bats in a fragmented tropical landscape. Sci Rep 8:3819. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-21999-2

Rojas D, Vale A, Ferrero V, Navarro L (2011) When did plants become important to leaf-nosed bats? Diversification of feeding habits in the family Phyllostomidae. Mol Ecol 20:2217–2228. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-294X.2011.05082.x

Santos BA, Arroyo-Rodríguez V, Moreno CE, Tabarelli M (2010) Edge-related loss of tree phylogenetic diversity in the severely fragmented Brazilian atlantic forest. PLoS ONE 5:e12625. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0012625

Santos BA, Tabarelli M, Melo FPL et al (2014) Phylogenetic impoverishment of amazonian tree communities in an experimentally fragmented forest landscape. PLoS ONE 9:e113109. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0113109

Scheffer M, van Nes EH (2006) Self-organized similarity, the evolutionary emergence of groups of similar species. Proc Natl Acad Sci 103:6230–6235. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0508024103

Shi JJ, Rabosky DL (2015) Speciation dynamics during the global radiation of extant bats. Evolution 69:1528–1545. https://doi.org/10.1111/evo.12681

Smith TW, Lundholm JT (2010) Variation partitioning as a tool to distinguish between niche and neutral processes. Ecography 33:648–655. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0587.2009.06105.x

Stegen JC, Hurlbert AH (2011) Inferring ecological processes from taxonomic, phylogenetic and functional trait β-diversity. PLoS ONE 6:e20906. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0020906

Stevens RD, Gavilanez MM (2015) Dimensionality of community structure: phylogenetic, morphological and functional perspectives along biodiversity and environmental gradients. Ecography 38:861–875. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecog.00847

Swenson NG (2011) Phylogenetic beta diversity metrics, trait evolution and inferring the functional beta diversity of communities. PLoS ONE 6:e21264. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0021264

Swenson NG (2014) Functional and phylogenetic ecology in R. Springer, New York

Tinoco BA, Santillán VE, Graham CH (2018) Land use change has stronger effects on functional diversity than taxonomic diversity in tropical Andean hummingbirds. Ecol Evol 8:3478–3490. https://doi.org/10.1002/ece3.3813

Tucker CM, Cadotte MW, Carvalho SB et al (2017) A guide to phylogenetic metrics for conservation, community ecology and macroecology: a guide to phylogenetic metrics for ecology. Biol Rev 92:698–715. https://doi.org/10.1111/brv.12252

Vamosi SM, Heard SB, Vamosi JC, Webb CO (2009) Emerging patterns in the comparative analysis of phylogenetic community structure. Mol Ecol 18:572–592. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-294X.2008.04001.x

Webb CO (2000) Exploring the phylogenetic structure of ecological communities: an example for rain forest trees. Am Nat 156:145–155

Young HS, McCauley DJ, Galetti M, Dirzo R (2016) Patterns, causes, and consequences of Anthropocene defaunation. Annu Rev Ecol Evol Syst 47:333–358. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-ecolsys-112414-054142

Acknowledgements

We thank J. L. Camargo, R. Hipólito, A. J. Ferreira for logistic support and the following people for help with fieldwork: F. Farneda, J. Palmeirim, P. Bobrowiec, G. Fernandez, M. Groenenberg, R. Marciente, I. Silva, J. Treitler, J. Carvalho, S. Farias, U. Capaverde, A. Reis, L. Queiroz, J. Menezes, O. Silva, and J. Tenaçol. We also thank Dirk Metzler for his feedback on the statistical analysis. We are further grateful to the Associate Editor and two reviewers for helpful comments.

Funding

The Portuguese Foundation for Science and Technology provided funds to C.F.J.M. (PTDC/BIA-BIC/111184/2009), R.R. (SFRH/BD/80488/2011) and A.L.-B. (PD/BD/52597/2014). S.G.A was supported by the Indonesia Endowment Fund for Education (LPDP). This research was conducted under ICMBio permit (26877-2) and constitutes publication number 771 in the BDFFP technical series.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

RR and AL conducted the fieldwork, SGA and CFJM formulated the idea, SGA performed the analysis, and SGA, RR, AL, and CFJM wrote the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Communicated by Raphael K. Didham.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Our study highlights the erosion of phylogenetic diversity of bat assemblages associated with habitat fragmentation and degradation in the world’s largest and longest-running whole-ecosystem fragmentation experiment. This work advances our understanding of the effects of habitat modification on bats as key ecosystem service providers in tropical ecosystems.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Aninta, S.G., Rocha, R., López-Baucells, A. et al. Erosion of phylogenetic diversity in Neotropical bat assemblages: findings from a whole-ecosystem fragmentation experiment. Biodivers Conserv 28, 4047–4063 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10531-019-01864-y

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10531-019-01864-y