Abstract

Purpose

Improved patient-provider relationships can positively influence patient outcomes. Sexual and gender minorities (SGM) represent a wide variety of marginalized populations. There is an absence of studies examining the inclusion of SGM-related health education within postgraduate training in anesthesia. This study’s objective was to perform an environmental scan of the educational content of North American obstetric anesthesia fellowship programs.

Methods

An online survey was developed based on a review of the existing literature assessing the presence of SGM content within other healthcare-provider curricula. The survey instrument was distributed electronically to 50 program directors of North American obstetric anesthesia fellowship programs. Survey responses were summarized using descriptive statistics.

Results

Survey responses were received from 30 of the 50 program directors (60%). Of these, 54% (14/26) felt their curriculum adequately prepares fellows to care for SGM patients, yet only 19% (5/26) of participants stated that SGM content was part of their curriculum and 31% (8/26) would like to see more incorporated in the future. Perceived lack of need was chosen as the biggest barrier to curricular inclusion of SGM education (46%; 12/26), followed by lack of available/interested faculty (19%; 5/26) and time (19%; 5/26).

Conclusions

Our results suggest that, although curriculum leaders appreciate that SGM patients are encountered within the practice of obstetric anesthesia, most fellowship programs do not explicitly include SGM curricular content. Nevertheless, there appears to be interest in developing SGM curricular content for obstetric anesthesia fellowship training. Future steps should include perspectives of trainees and patients to inform curricular content.

Résumé

Objectif

L’amélioration des relations patient-fournisseur peut avoir une influence positive sur les devenirs des patients. Les minorités sexuelles et de genre (MSG) représentent une vaste diversité de populations marginalisées. Aucune étude n’a examiné l’inclusion d’éducation médicale liée aux MSG dans le cadre de la formation surspécialisée en anesthésie. L’objectif de cette étude était de mener une enquête générale sur le contenu éducatif des programmes de fellowship nord-américains en anesthésie obstétricale.

Méthode

Un sondage électronique a été mis au point en se fondant sur la littérature existante afin d’évaluer l’offre de contenu traitant des MSG dans le cadre d’autres programmes de cours destinés aux fournisseurs de soins de santé. Le sondage a été distribué électroniquement à 50 directeurs de programmes de fellowship en anesthésie obstétricale en Amérique du Nord. Les réponses au sondage ont été résumées à l’aide de statistiques descriptives.

Résultats

Des réponses au sondage de 30 des 50 directeurs de programme ont été reçues (60 %). Parmi ces réponses, 54 % (14/26) étaient d’avis que leur programme de cours était adapté pour préparer les fellows à s’occuper de patients issus des MSG, mais seuls 19 % (5/26) des participants déclaraient que du contenu spécifique portant sur les MSG était intégré dans leur programme, et 31 % (8/26) aimeraient voir davantage de contenu pertinent intégré à l’avenir. L’absence perçue de besoin a été retenue comme l’obstacle le plus important à l’inclusion de formation concernant les MSG dans le programme de cours (46 %; 12/26), suivie par le manque de personnel disponible / intéressé (19 %; 5/26) et de temps (19 %; 5/26).

Conclusion

Nos résultats suggèrent que bien que les directeurs de programmes soient conscients que des patients issus des MSG soient suivis dans la pratique de l’anesthésie obstétricale, la plupart des programmes de fellowship n’incluent pas explicitement de contenu éducatif lié aux MSG. Toutefois, il semble y avoir un intérêt pour la mise au point de contenu éducatif pertinent aux MSG dans le cadre des programmes de fellowship en anesthésie obstétricale. L’étape suivante serait d’inclure les opinions des fellows et des patients afin de guider le contenu des programmes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Obstetric anesthesia involves caring for patients during an emotional and often stressful period of their lives.1 Anesthesiologists need to communicate effectively with parturients, choosing their language as a key tactic in reducing stress on the labour ward. Improved patient-provider communication and rapport may contribute to improved maternal self-care,1 decreased analgesic requirements during labour,2 increased participation in shared decision-making,3 improved neonatal Apgar scores,2,4 and decreased risk of postpartum depression.4 Certain patients who may already be vulnerable to poor health outcomes, inadequate access to care, or structural stigmatization require particular attention to appreciate the impact of pre-existing health inequities.5,6 Corrigan et al. describes structural stigmatization as being “formed by sociopolitical forces and represents the policies of private and governmental institutions that restrict the opportunities of stigmatized groups”.5

Sexual and gender minorities (SGM) represent a wide variety of marginalized patient populations.7,8,9 The term SGM encompasses the two-spirit, lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, intersex, queer, non-binary, and asexual communities. A brief list of relevant terms and their definitions can be found in Table 1. Sexual and gender minority has been chosen for use in this study as a broadly inclusive term, but it is important to acknowledge that health inequities affecting members of these SGM communities vary widely. Each SGM community has faced their own obstacles from a variety of perspectives—historical, social, economic, political, and cultural—and thus will have unique concerns relevant to the provision of high-quality healthcare.

Individuals that identify as SGM face many barriers when it comes to accessing healthcare services. These individuals do not necessarily present as visible minorities, making it even more important to avoid making assumptions about a patient’s gender identity, sexual orientation, and relationships to the people who may accompany them during clinical encounters. Issues surrounding privacy, proper documentation, and inpatient room assignment require particular attention.10 When SGM individuals attempt to access medical services, encounters range from refusal of care to interactions with healthcare providers that are largely uneducated about the issues relevant to their care.7,11,12 Sexual and gender minority individuals may be at increased risk of substance and alcohol abuse, smoking, homelessness, and depression, including self-harm and suicidal attempts, all of which are important social determinants of health that can impact perioperative outcomes.13,14,15 Lesbian and bisexual women may have increased rates of obesity, heart disease, and postpartum depression compared with heterosexual women.16,17 Transgender patients undergoing hormone therapy may be at elevated risk of venous thromboembolism and may have undergone airway surgery.10 With successful deliveries following uterine transplant, the question of uterine transplant and delivery for transgender women is a real possibility.18,19 All of these issues are relevant in the provision of anesthesia care for obstetric patients.

There is a paucity of SGM-related content in many areas of medical training. In a survey of emergency medicine residency program directors, Moll et al.20 found that most programs did not contain lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT)-specific curricular content. Related studies looking at undergraduate medical training,21 various residency programs,22,23,24,25 and public health schools8 describe similar results. Lack of healthcare provider education is an identified barrier to accessing equitable healthcare for members of the SGM communities,11,26,27,28,29 highlighting the need for more research and formalized inclusion within medical training.11,29,30,31,32,33

The gap in medical education research represents a health inequity and one could suggest that failure to address inequities like this would be unethical.34 Health inequities not only exemplify, but also continue to perpetuate, injustices faced by marginalized groups.35 The ethical obligations relating to these injustices are under the same protections from the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, regardless of sexual orientation or gender.36 The objective of this study was to perform an environmental scan of the educational content within obstetric anesthesia fellowship programs in North America.

Methods

Institutional research ethics committee approval was obtained on November 17, 2017 (IWK REB#1022927). This manuscript adheres to the CHERRIES checklist, available on the EQUATOR Network.37 The institutional research ethics committee waived the need for written informed consent.

Instrument development

Few studies have assessed the presence of SGM education within medical and healthcare provider curricula, so no validated surveys are available.8,9,20,21,22,23,24,25 Components of the literature, specifically an article by Burns et al.,38 aided the design and creation of a 32-item questionnaire (eAppendix, available as Electronic Supplementary Material), composed of both open and closed questions. Using an iterative process, a total of 12 individuals consisting of healthcare providers and SGM-identified people from within our local network of colleagues, researchers, and community members provided feedback to develop and refine the survey instrument. These 12 individuals were compromised of physicians, some of whom have had experience as program directors, people who openly identify as SGM, a nurse, a human rights lawyer, and a sociology professor. These individuals were contacted via email and asked several questions to guide their feedback, in addition to any other comments they offered. They were asked to comment on clarity of language, ambiguity in the questions or responses, appropriateness of questions for our intended study population, and use of appropriate terminology. Initially, we contacted three healthcare providers and three SGM-identified people for feedback. After revising the survey instrument based on these responses, we repeated the process using the same ratio with six different individuals. The second iteration also served as a pilot test prior to survey distribution.

The finalized survey instrument consisted of an introductory screen containing an abbreviated version of our cover letter followed by the questionnaire, which spanned a total of five screens (pages), with five to nine items per page. When appropriate, adaptive questioning was used with specific instructions (e.g., “If you answered yes to question [x]”). Participants were able to navigate between screens with use of “back” and “next” buttons, which they could use to review and/or change their responses prior to submission.

Data collection

The survey was uploaded to SelectSurveys™ (Atomic Design; Kansas City, MO, USA) and distributed to program directors of obstetric anesthesia fellowship programs throughout North America. The contact information for these individuals was publicly available on the fellowship directory listed on the Society for Obstetric Anesthesia and Perinatology website (https://soap.org/fellowship-directory.php). At the time of study distribution, there were 49 obstetric anesthesia fellowship programs listed in North America. Two of the programs had two separate individuals listed as the program directors. In these cases, everyone was contacted. One of the authors (R.G.) of this study is an obstetric anesthesia fellowship director and was therefore excluded from participation. This gave 50 potential participants.

A modified Dillman approach was used to remind and encourage participation over a seven-week period.39 The initial email introduced the research question, provided a link to the survey tool, and confirmed consent to participate in the study. A reminder email with the survey link was sent two weeks and seven weeks after the initial contact. Participants were given the opportunity to enter a draw for one of two Amazon gift cards (valued at USD 100 each) as an incentive. Potential participants were informed of the project components on a cover page of the survey prior to completing any questions. The cover page stated that consent for participation would be implied by responding to the survey. Consent could be withdrawn by contacting a member of the research team. Survey data were collected anonymously, without identification of individuals, affiliated institutions, or hospitals. Respondents’ IP addresses were used to prevent multiple responses from the same individual.

Statistical analysis

Data were exported from SelectSurveys™. Participant responses were summarized with descriptive statistics as presented below. Denominators (indicated by n) reflect the number of entered participant responses, meaning that if a participant skipped a question, they would be omitted from the respective denominator.

Results

Thirty of 50 program directors participated in the survey (60% response rate). Demographics of the participants are summarized in Table 2. Participants were provided with a list of terminology for the survey and asked whether fellows have provided care for SGM individuals during their training. Ninety-six percent (25/26) of participants selected one or more of the listed options. The most commonly selected options were lesbian (92.3%; 24/26 responses), bisexual (61.5%; 16/26), gay (53.8%; 14/26), and trans (42.3%; 11/26). Further inquiry into institutional policies, practices, and resources has been summarized in Table 3.

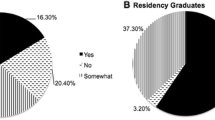

Ninety-six percent (25/26 responses) of participants stated that the anesthesiologists at their institution were adequately equipped (from a cognitive and/or emotional perspective) to provide care for SGM individuals, and 54% (14/26) of participants stated that their fellowship program adequately prepares fellows to provide care to SGM individuals. When asked about curricular content to support this, 43% (12/28) of participants indicated that their current curriculum addresses the needs of any marginalized populations (including but not limited to SGM), while only 21% (6/28) indicated that their curriculum explicitly addresses the needs of any SGM populations. The Figure shows the distribution of various forms of teaching utilized within the participants’ curricula, as well as the forms of teaching utilized to address SGM topics (if included at all). When given the opportunity to provide an example of how their curriculum includes SGM health education, one participant stated that they have “lots of grand rounds, journal clubs, etc. on various aspects” because they were at an institution that provides transgender surgeries.

Forms of teaching utilized in training programs’ curricula overall compared with forms of teaching utilized for SGM content. The y axis indicates the percentage of respondents who selected each of the options indicated on the x axis. SGM = sexual and gender minorities; PBL = problem or case-based learning; SP = simulated patient.

While 54% (14/26) of participants felt that their curriculum adequately prepares fellows to care for SGM individuals, 38% (10/26) were unsure and 8% (2/26) felt it did not. Nevertheless, 31% (8/26) of participants indicated that they would like to see more SGM content incorporated into their curriculum in the future. Forty-six percent (12/26) of all respondents stated that they were unsure if they would like to see more SGM content incorporated into their curriculum in the future.

Table 4 shows participant responses when asked about perceived barriers to inclusion of SGM health education within their curricula. Lack of perceived need was the most commonly identified barrier (46%; 12/26) to inclusion of SGM curricular content. One participant identified the “lack of OB-anesthesia-specific curriculum” as a barrier in their program.

Discussion

Although there are some obstetric anesthesia fellowship programs with SGM curricular content, the fact that only half of participants feel their curriculum adequately prepares fellows to care for SGM individuals suggests there is room for improvement. When asked whether fellows have provided care for SGM individuals during their training, 96% (25/26) of participants selected one or more of the listed options, suggesting that SGM individuals are nearly ubiquitous within their practice of obstetric anesthesia. There appears to be an interest in incorporating future SGM curricular content. Teaching modalities used to address SGM content are similar in distribution to modalities used in the overall curricula, albeit in smaller numbers, except for the absence of simulation and simulated patient encounters.

Overall, our results suggest that participants feel reasonably confident in the quality of care that SGM patients receive from obstetric anesthesiologists at their institutions (25/26, 96%), although slightly more than half (14/26, 54%) feel that their curriculum adequately prepares fellows to care for SGM patients. These results are not generalizable outside of Canada and the United States, because of differences in educational structure and cultural differences. Existing literature, especially from the perspective of SGM individuals, argues that there is a significant knowledge gap amongst healthcare providers that limits their ability to provide optimal care to patients from these communities.11,29,30,31,32,33 Nevertheless, none of this literature is specific to the context of obstetric anesthesia. This limits the authors’ ability to draw further conclusions regarding the current quality of SGM patient care in our clinical context as obstetric anesthesiologists.

This study has several limitations. There was a limited number of potential participants; even with a reasonable response rate, the sample size is small. Although we utilized the modified Dillman method, we achieved a response rate of 60% (30/50 potential responses).39 Program directors receive many emails, including requests for participation in surveys. Potential participants may have overlooked our emails or had other higher priority tasks to attend to. The end of year holiday season in December did fall within our data collection period, which may have negatively impacted our response rate. Furthermore, there was concern that collection of geographical information could potentially identify participants, so this was not included. As a result, we are unable to comment on any potential regional differences amongst training programs. Without any previous studies on this topic in the anesthesia literature, there were no previously validated survey instruments to use that would adequately address our objectives. Although we did undertake face- and content validity assessments, it is still possible that our survey instrument was not able to accurately capture the desired information.

Ninety-six percent (25/26) of participants self-reported that the anesthesiologists at their institutions were adequately equipped to provide care for SGM individuals, but only 54% (14/26) of participants felt that their curriculum adequately prepares fellows to provide care for SGM individuals. There are many possible reasons to explain this discrepancy, including social desirability bias. One might also question if respondents feel as though their fellows would be getting the skills and knowledge to provide care to SGM individuals from resources outside of their program’s curriculum.

The absence of literature describing the SGM patient perspective in the context of obstetric anesthesia care is a major limitation. It is challenging, if not impossible, to truly assess the current quality of care provided by obstetric anesthesiologists when there is no benchmark to strive for. Although Tollinche et al. makes some specific suggestions for perioperative care of transgender patients, they are not all generalizable to the peripartum context or to SGM individuals who are not transgender.10 Of the 62% (16/26) of participants stating that the anesthesiologists in their institution and/or department were provided with cultural competency training, 75% (12/16) indicated that issues pertaining to SGM communities were addressed within said training. Our study did not explore any details about what that cultural competency training included, and it should be noted that inclusion of SGM content may not actually translate into improved patient care. This is another example that highlights the need for further research exploring the patient perspective.

Another limitation relates back to the original impetus behind this study. It is well-documented that many healthcare providers have not received adequate training about SGM health issues, which could mean that the language used in our survey may not have been properly understood by participants.7,11,12,13,21,28,29,32,33 We attempted to minimize this limitation by including definitions in the survey instrument. Additionally, despite all efforts to collect data in an anonymous fashion, there may have still been an element of social desirability bias present. As program directors, participants may have an unconscious desire to portray their programs in a positive light. For example, although no participants indicated that opposition was a barrier to inclusion of SGM content in their curricula, the most frequently reported barrier was perceived lack of need (46%; 12/26), which may represent a more socially acceptable way of describing veiled opposition. Our intention was that this bias would be minimized by collecting data anonymously. Perhaps this bias could have been minimized if fellows were also included as survey participants.

This study is the first step in building a foundation from which to develop SGM-inclusive content to integrate into existing curricula for obstetric anesthesia fellowship training. Anesthesiologists are widely recognized as leaders in patient safety, which encompasses more than technical skills and objective measures of quality assurance.40 All patients are entitled to receive care in a safe space. For marginalized populations, that have often experienced systemic stigmatization to varying degrees, this demands avoidance of further structural traumatization.10,41 The obstetric anesthesiologist, as a peripartum physician,42 can have a profound impact on a patient’s birth experience. We have a responsibility to advocate for inclusive forms and policies, as well as to actively discourage heteronormativity in a realm that is all too easily centred on just that.43

Educators and training programs can create culture within an institution, as well as on a larger scale within communities. The identification of gaps in various stages of medical education is a necessary step to improve provision of care for all patients. By exploring what future obstetric anesthesiologists are currently being taught, we can improve upon efforts to shape a medical culture that supports equitable patient-centred care.

Sexual and gender minorities content could be integrated into existing curricula in multiple formats, including didactic lectures, simulations, and grand rounds. Discussions around the inherent heteronormativity present throughout the peripartum period could be valuable to explore pre-existing stereotypes and demonstrate inclusive behaviour. The trauma-informed care model is applicable to the care of SGM individuals, since they are more likely to have experienced trauma in the past.7 Trauma-informed care aims to adjust the approach to trauma in a manner that realizes its full impact, recognizes signs indicative of trauma (previous or ongoing), and responds by integrating this knowledge at all levels of care and actively avoids further traumatization of the affected individual.44

Future development of an obstetric anesthesia-specific SGM curriculum poses its own challenges. Many respondents (46%; 12/26) were unsure if they would like to see more SGM curricular content. Unfortunately, our survey instrument did not provide any means to explore the possible reasons behind this uncertainty, but it may be worthwhile to examine more closely in future research. To complement this study, the authors plan to adapt the survey instrument to conduct a similar study of the current curriculum for anesthesia residency training in Canada. Results from both studies, along with input from trainees, curriculum leaders, and SGM individuals, can be utilized to create the first anesthesia-specific SGM curricula for residents and fellows.

References

Nicoloro-SantaBarbara J, Rosenthal L, Auerbach MV, Kocis C, Busso C, Lobel M. Patient-provider communication, maternal anxiety, and self-care in pregnancy. Soc Sci Med 2017; 190: 133-40.

Bohren MA, Hofmeyr GJ, Sakala C, Fukuzawa RK, Cuthbert A. Continuous support for women during childbirth. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2017. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD003766.pub6.

Waldenstrom U, Brown S, McLachlan H, Forster D, Brennecke S. Does team midwife care increase satisfaction with antenatal, intrapartum, and postpartum care? A randomized controlled trial. Birth 2000; 27: 156-67.

Collins NL, Dunkel-Schetter C, Lobel M, Scrimshaw SCM. Social support in pregnancy: psychosocial correlates of birth outcomes and postpartum depression. J Pers Soc Psychol 1993; 65: 1243-58.

Corrigan PW, Watson AC, Heyrman ML, et al. Structural stigma in state legislation. Psychiatr Serv 2005; 56: 557-63.

Link BG, Phelan JC. Conceptualizing stigma. Annu Rev Sociol 2001; 27: 363-85.

Institute of Medicine. The Health of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender People: Building a Foundation for Better Understanding. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2011. Available from URL: https://doi.org/10.17226/13128 (accessed November 2019).

Talan AJ, Drake CB, Glick JL, Claiborn CS, Seal D. Sexual and gender minority health curricula and institutional support services at U.S. schools of public health. J Homosex 2017; 64: 1350-67.

Hillenburg KL, Murdoch-Kinch CA, Kinney JS, Temple H, Inglehart MR. LGBT coverage in U.S. dental schools and dental hygiene programs: results of a national survey. J Dent Educ 2016; 80: 1440-9.

Tollinche LE, Walters CB, Radix A, et al. The perioperative care of the transgender patient. Anesth Analg 2018; 127: 359-66.

Samuels EA, Tape C, Garber N, Bowman S, Choo EK. “Sometimes you feel like the freak show”: a qualitative assessment of emergency care experiences among transgender and gender-nonconforming patients. Ann Emerg Med 2018; 71(170–82): e1.

Eliason MJ, Shope.R. Does “Don’t Ask Don’t Tell” apply to health care? Lesbian, gay, and bisexual people’s disclosure to health care providers. J Gay Lesbian Med Assoc 2001; 5: 125-34.

Marshal MP, Friedman MS, Stall R, et al. Sexual orientation and adolescent substance use: a meta-analysis and methodological review. Addiction 2008; 103: 546-56.

Almeida J, Johnson RM, Corliss HL, Molnar BE, Azrael D. Emotional distress among LGBT youth: the influence of perceived discrimination based on sexual orientation. J Youth Adolesc 2009; 38: 1001-14.

Rew L, Fouladi RT, Yockey RD. Sexual health practices of homeless youth. J Nurs Scholarsh 2002; 34: 139-45.

Diamant AL, Wold C. Sexual orientation and variation in physical and mental health status among women. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2003; 12: 41-9.

Flanders CE, Gibson MF, Goldberg AE, Ross LE. Postpartum depression among visible and invisible sexual minority women: a pilot study. Arch Womens Ment Health 2016; 19: 299-305.

Park M. Baby is first to be born in US after uterus transplant, hospital says. CNN. Updated December 4, 2017. Available from URL: https://www.cnn.com/2017/12/04/health/uterus-transplant-us-baby-birth/index.html (accessed November 2019).

Lerner T, Ejzenberg D, Pereyra EA, Soares Júnior JM, Baracat EC. What are the possibilities of uterine transplantation in transgender patients? Rev Bras Ginecol Obstet 2017; 39: 521-2.

Moll J, Krieger P, Moreno-Walton L, et al. The prevalence of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender health education and training in emergency medicine residency programs: what do we know? Acad Emerg Med 2014; 21: 608-11.

Obedin-Maliver J, Goldsmith ES, Stewart L, et al. Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender-related content in undergraduate medical education. JAMA 2011; 306: 971-7.

Coutin A, Wright S, Li C, Fung R. Missed opportunities: are residents prepared to care for transgender patients? A study of family medicine, psychiatry, endocrinology, and urology residents. Can Med Educ J 2018; 9: e41-55.

Davidge-Pitts C, Nippoldt TB, Danoff A, Radziejewski L, Natt N. Transgender health in endocrinology: current status of endocrinology fellowship programs and practicing clinicians. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2017; 102: 1286-90.

Dy GW, Osbun NC, Morrison SD, Grant DW, Merguerian PA; Transgender Education Study Group. Exposure to and attitudes regarding transgender education among urology residents. J Sex Med 2016; 13: 1466-72.

Morrison SD, Dy GW, Chong HJ, et al. Transgender-related education in plastic surgery and urology residency programs. J Grad Med Educ 2017; 9: 178-83.

Rossman K, Salamanca P, Macapagal K. A qualitative study examining young adults’ experiences of disclosure and nondisclosure of LGBTQ identity to health care providers. J Homosex 2017; 64: 1390-410.

Sallans RK. Lessons from a transgender patient for health care professionals. AMA J Ethics 2016; 18: 1139-46.

Rondahl G. Students’ inadequate knowledge about lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender persons. Int J Nurs Educ Scholarsh 2009. DOI: https://doi.org/10.2202/1548-923X.1718.

Alpert AB, CichoskiKelly EM, Fox AD. What lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, and intersex patients say doctors should know and do: a qualitative study. J Homosex 2017; 64: 1368-89.

Abdessamad HM, Yudin MH, Tarasoff LA, Radford KD, Ross LE. Attitudes and knowledge among obstetrician-gynecologists regarding lesbian patients and their health. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2013; 22: 85-93.

Rossi AL, Lopez EJ. Contextualizing competence: language and LGBT-based competency in health care. J Homosex 2017; 64: 1330-49.

Stott DB. The training needs of general practitioners in the exploration of sexual health matters and providing sexual healthcare to lesbian, gay and bisexual patients. Med Teach 2013; 35: 752-9.

Unger CA. Care of the transgender patient: a survey of gynecologists’ current knowledge and practice. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2015; 24: 114-8.

Braveman P, Gruskin S. Defining equity in health. J Epidemiol Community Health 2003; 57: 254-8.

Jones CM. The moral problem of health disparities. Am J Public Health 2010; 100: S47-51.

Government of Canada. Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms. Constitution Act, 1982. Available from URL: https://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/const/page-15.html (accessed November 2019).

Eysenbach G. Improving the quality of Web surveys: the Checklist for Reporting Results of Internet E-Surveys (CHERRIES). J Med Internet Res 2004; 6. DOI: https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.6.3.e34.

Burns KE, Duffett M, Kho ME, et al. A guide for the design and conduct of self-administered surveys of clinicians. CMAJ 2008; 179: 245-52.

Dillman DA, Smyth JD, Christian LM. Internet, Phone, Mail, and Mixed-Mode Surveys: The Tailored Design Method. 4th ed. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley; 2014 .

Leape LL. Error in medicine. JAMA 1994; 272: 1851-7.

Quiros L, Berger R. Responding to the sociopolitical complexity of trauma: an integration of theory and practice. J Loss Trauma 2015; 2: 149-59.

Moaveni DM, Cohn JH, Zahid ZD, Ranasinghe JS. Obstetric anesthesiologists as perioperative physicians: Improving peripartum care and patient safety. Curr Anesthesiol Rep 2015; 5: 65-73.

Searle J, Goldberg L, Aston M, Burrow S. Accessing new understandings of trauma-informed care with queer birthing women in a rural context. J Clin Nurs 2017; 26: 3576-87.

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. SAMHSA’s concept of trauma and guidance for a trauma-informed approach. HHS Publication No. (SMA) 14-4884. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2014. Available from URL: https://store.samhsa.gov/system/files/sma14-4884.pdf (accessed November 2019).

Author contributions

Hilary MacCormick helped with literature review, study design, development of the survey instrument, preparation of the protocol and manuscript, and data collection and analysis. Ronald B. George helped with the study design, development of the survey instrument, preparation of the manuscript, and statistical analysis

Conflicts of interest

None.

Funding

Funding for the survey incentive received from the Department of Anesthesia, Pain Management, and Perioperative Medicine, Dalhousie University, Halifax, NS, Canada.

Editorial responsibility

This submission was handled by Dr. Hilary P. Grocott, Editor-in-Chief, Canadian Journal of Anesthesia.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

MacCormick, H., George, R.B. Sexual and gender minorities educational content within obstetric anesthesia fellowship programs: a survey. Can J Anesth/J Can Anesth 67, 532–540 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12630-019-01562-x

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12630-019-01562-x