Abstract

Summary

We investigated associations between bone mineral content (BMC) and bone-related biomarkers (BM) in pre-and early pubertal children of both sexes. In this population, we found that bone turnover markers explain a small part of BMC variance.

Introduction

It is still debated whether BM including bone turnover markers (BTM), sex hormones and calciotropic (including cortisol) hormones provide information on BMC changes during growth.

Methods

Three hundred fifty-seven girls and boys aged 6 to 13 years were included in this study. BM was measured at baseline and BMC twice at 9 months and 4 years using DXA. Relationship between BMs was assessed using principal component analysis (PCA). BM was tested in its ability to explain BMC variation by using structural equation modelling (SEM) on cross-sectional data. Longitudinal data were used to further assess the association between BM and BMC variables.

Results

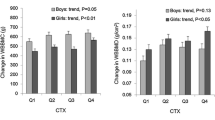

BMC and all BMs, except calciotropic hormones, increased with age. PCA in BM revealed a three-factor solution (BTM, sex hormones and calciotropic hormones). In the SEM, age accounted for 61% and BTM for 1.2% of variance in BMC (cross-sectional). Neither sex nor calciotropic hormones were BMC explanatory variables. In the longitudinal models (with single BM as explanatory variables), BMC, age and sex at baseline accounted for 79–81% and 70–75% in BMC variance at 9 months and 4 years later, respectively. P1NP was consistently associated with BMC.

Conclusion

BMC strongly tracks in pre- and early pubertal children. In this study, only a small part of BMC variance was explained by single BTM at the beginning of pubertal growth.

Similar content being viewed by others

Abbreviations

- BM:

-

Biomarkers (including all markers measured in the blood)

- BTM:

-

Bone turnover marker

- CORT:

-

Cortisol

- CTX:

-

C-terminal telopeptide

- DHEAS:

-

Dehydroepiandrosterone sulphate

- DXA:

-

Dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry

- E2 :

-

Estradiol

- FN:

-

Femoral neck

- LS:

-

Lumbar spine

- OCN :

-

Osteocalcin

- 25(OH)D:

-

25-Hydroxy vitamin D/calcifediol

- PCA:

-

Principal component analysis

- P1NP :

-

N-terminal propeptide

- PROGE:

-

Progesterone

- PTH:

-

Intact parathyroid hormone

- SEM:

-

Structural equation modelling

- SHBG:

-

Sex hormone-binding globulin

- TEST:

-

Testosterone

- WB:

-

Whole body

References

Rizzoli R, Bianchi ML, Garabedian M, McKay HA, Moreno LA (2010) Maximizing bone mineral mass gain during growth for the prevention of fractures in the adolescents and the elderly. Bone 46:294–305

Weaver CM, Gordon CM, Janz KF, Kalkwarf HJ, Lappe JM, Lewis R, O'Karma M, Wallace TC, Zemel BS (2016) The National Osteoporosis Foundation's position statement on peak bone mass development and lifestyle factors: a systematic review and implementation recommendations. Osteoporos Int 27:1281–1386

Seeman E, Tsalamandris C, Formica C (1993) Peak bone mass, a growing problem? Int J Fertil Menopausal Stud 38(Suppl 2):77–82

Soyka LA, Fairfield WP, Klibanski A (2000) Hormonal determinants and disorders of peak bone mass in children1. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 85:3951–3963

Holick MF (2004) Sunlight and vitamin D for bone health and prevention of autoimmune diseases, cancers, and cardiovascular disease. Am J Clin Nutr 80:1678s–1688s

Dawson-Hughes B, Heaney RP, Holick MF, Lips P, Meunier PJ, Vieth R (2005) Estimates of optimal vitamin D status. Osteoporos Int 16:713–716

Jurimae J (2010) Interpretation and application of bone turnover markers in children and adolescents. Curr Opin Pediatr 22:494–500

Vasikaran S, Eastell R, Bruyère O et al (2011) Markers of bone turnover for the prediction of fracture risk and monitoring of osteoporosis treatment: a need for international reference standards. Osteoporos Int 22:391–420

Eapen E, Grey V, Don-Wauchope A, Atkinson SA (2008) Bone health in childhood: usefulness of biochemical biomarkers. EJIFCC 19:123–136

Rauchenzauner M, Schmid A, Heinz-Erian P, Kapelari K, Falkensammer G, Griesmacher A, Finkenstedt G, Hogler W (2007) Sex- and age-specific reference curves for serum markers of bone turnover in healthy children from 2 months to 18 years. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 92:443–449

Mora S, Pitukcheewanont P, Kaufman FR, Nelson JC, Gilsanz V (1999) Biochemical markers of bone turnover and the volume and the density of bone in children at different stages of sexual development. J Bone Miner Res 14:1664–1671

Szulc P, Seeman E, Delmas PD (2000) Biochemical measurements of bone turnover in children and adolescents. Osteoporos Int 11:281–294

van Coeverden SC, Netelenbos JC, de Ridder CM, Roos JC, Popp-Snijders C, Delemarre-van de Waal HA (2002) Bone metabolism markers and bone mass in healthy pubertal boys and girls. Clin Endocrinol 57:107–116

van der Sluis IM, Hop WC, van Leeuwen JP, Pols HA, de Muinck Keizer-Schrama SM (2002) A cross-sectional study on biochemical parameters of bone turnover and vitamin d metabolites in healthy Dutch children and young adults. Horm Res 57:170–179

Vandewalle S, Taes Y, Fiers T, Toye K, Van Caenegem E, Roggen I, De Schepper J, Kaufman JM (2014) Associations of sex steroids with bone maturation, bone mineral density, bone geometry, and body composition: a cross-sectional study in healthy male adolescents. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 99:E1272–E1282

Csakvary V, Erhardt E, Vargha P, Oroszlan G, Bodecs T, Torok D, Toldy E, Kovacs GL (2012) Association of lean and fat body mass, bone biomarkers and gonadal steroids with bone mass during pre- and midpuberty. Horm Res Paediatr 78:203–211

Csakvary V, Puskas T, Oroszlan G, Lakatos P, Kalman B, Kovacs GL, Toldy E (2013) Hormonal and biochemical parameters correlated with bone densitometric markers in prepubertal Hungarian children. Bone 54:106–112

Yilmaz D, Ersoy B, Bilgin E, Gümüşer G, Onur E, Pinar ED (2005) Bone mineral density in girls and boys at different pubertal stages: relation with gonadal steroids, bone formation markers, and growth parameters. J Bone Miner Metab 23:476–482

Jolliffe IT (2002) Principal component analysis. Springer, New York

Kline RB (2005) Principles and practice of structural equation modeling, 2nd edn. Guilford Press, New York

Zahner L, Puder JJ, Roth R, Schmid M, Guldimann R, Puhse U, Knopfli M, Braun-Fahrlander C, Marti B, Kriemler S (2006) A school-based physical activity program to improve health and fitness in children aged 6-13 years ("Kinder-Sportstudie KISS"): study design of a randomized controlled trial [ISRCTN15360785]. BMC Public Health 6:147

Meyer U, Romann M, Zahner L, Schindler C, Puder JJ, Kraenzlin M, Rizzoli R, Kriemler S (2011) Effect of a general school-based physical activity intervention on bone mineral content and density: a cluster-randomized controlled trial. Bone 48:792–797

Rasmussen AR, Wohlfahrt-Veje C, Tefre de Renzy-Martin K, Hagen CP, Tinggaard J, Mouritsen A, Mieritz MG, Main KM (2015) Validity of self-assessment of pubertal maturation. Pediatrics 135:86–93

de Onis M, Onyango AW, Borghi E, Siyam A, Nishida C, Siekmann J (2007) Development of a WHO growth reference for school-aged children and adolescents. Bull World Health Organ 85:660–667

Meyer U, Ernst D, Zahner L, Schindler C, Puder JJ, Kraenzlin M, Rizzoli R, Kriemler S (2013) 3-Year follow-up results of bone mineral content and density after a school-based physical activity randomized intervention trial. Bone 55:16–22

Zemel BS, Kalkwarf HJ, Gilsanz V et al (2011) Revised reference curves for bone mineral content and areal bone mineral density according to age and sex for black and non-black children: results of the bone mineral density in childhood study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 96:3160–3169

Keel C, Kraenzlin ME, Kraenzlin CA, Muller B, Meier C (2010) Impact of bisphosphonate wash-out prior to teriparatide therapy in clinical practice. J Bone Miner Metab 28:68–76

Schmidt-Gayk H, Spanuth E, Kotting J, Bartl R, Felsenberg D, Pfeilschifter J, Raue F, Roth HJ (2004) Performance evaluation of automated assays for beta-CrossLaps, N-MID-Osteocalcin and intact parathyroid hormone (BIOROSE Multicenter Study). Clin Chem Lab Med 42:90–95

Janssen MJ, Wielders JP, Bekker CC, Boesten LS, Buijs MM, Heijboer AC, van der Horst FA, Loupatty FJ, van den Ouweland JM (2012) Multicenter comparison study of current methods to measure 25-hydroxyvitamin D in serum. Steroids 77:1366–1372

Devine A, Dick IM, Dhaliwal SS, Naheed R, Beilby J, Prince RL (2005) Prediction of incident osteoporotic fractures in elderly women using the free estradiol index. Osteoporos Int 16:216–221

Bui HN, Sluss PM, Hayes FJ, Blincko S, Knol DL, Blankenstein MA, Heijboer AC (2015) Testosterone, free testosterone, and free androgen index in women: reference intervals, biological variation, and diagnostic value in polycystic ovary syndrome. Clin Chim Acta 450:227–232

Rosseel Y (2012) lavaan: an R package for structural equation modeling. J Stat Softw 1(2)

Schweizer K (2010) Some guidelines concerning the modeling of traits and abilities in test construction. Eur J Psychol Assess 26:1–2

Berk R (1990) A primer on robust regression. In: Fox J, Long JS (eds) Modern Methods of Data Analysis. Sage, Newbury Park, pp 292–324

Saggese G, Baroncelli GI, Bertelloni S (2002) Puberty and bone development. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab 16:53–64

Kalkwarf HJ, Gilsanz V, Lappe JM, Oberfield S, Shepherd JA, Hangartner TN, Huang X, Frederick MM, Winer KK, Zemel BS (2010) Tracking of bone mass and density during childhood and adolescence. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 95:1690–1698

Chevalley T, Bonjour JP, van Rietbergen B, Ferrari S, Rizzoli R (2014) Tracking of environmental determinants of bone structure and strength development in healthy boys: an eight-year follow up study on the positive interaction between physical activity and protein intake from prepuberty to mid-late adolescence. J Bone Miner Res 29:2182–2192

Yang Y, Wu F, Winzenberg T, Jones G (2017) Tracking of areal bone mineral density from age eight to young adulthood and factors associated with deviation from tracking: a 17-yr prospective cohort study. J Bone Miner Res

Jones RA, Hinkley T, Okely AD, Salmon J (2013) Tracking physical activity and sedentary behavior in childhood: a systematic review. Am J Prev Med 44:651–658

Gafni RI, Baron J (2007) Childhood bone mass acquisition and peak bone mass may not be important determinants of bone mass in late adulthood. Pediatrics 119(Suppl 2):S131–S136

Adam EK, Quinn ME, Tavernier R, McQuillan MT, Dahlke KA, Gilbert KE (2017) Diurnal cortisol slopes and mental and physical health outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychoneuroendocrinology 83:25–41

La'ulu SL, Roberts WL (2010) Performance characteristics of six intact parathyroid hormone assays. Am J Clin Pathol 134:930–938

Hutcheon JA, Chiolero A, Hanley JA (2010) Random measurement error and regression dilution bias. BMJ 340:c2289

Frank GR (2003) Role of estrogen and androgen in pubertal skeletal physiology. Med Pediatr Oncol 41:217–221

van Rijn RR, van der Sluis IM, Link TM, Grampp S, Guglielmi G, Imhof H, Gluer C, Adams JE, van Kuijk C (2003) Bone densitometry in children: a critical appraisal. Eur Radiol 13:700–710

Acknowledgements

We sincerely thank all children, teachers and parents for taking part in the study. We greatly appreciate the help of Giulio Conicella, Chantal Genet and Claude Kränzlin for their competent help in the bone measurements. We thank the foundation AETAS, Switzerland, for the use of their DXA-bus, the Swiss Heart Foundation for financial support of the current study and the funders of the initial study (KISS) including the Federal Council of Sports, Magglingen, Switzerland (grant number SWI05-013), and the Swiss National Foundation (grant number PMPDB-114401). And finally, also thanks to Erin Ashley West for proof-reading the manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded by the Swiss Heart Foundation. Funding for the initial trial (Effect of a general school-based physical activity intervention on bone mineral content and density) was provided by Swiss Federal Office of Sports and the Swiss National Science Foundation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

None.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

ESM 1

Fig. 1 appendix. Study flow diagram: relation between bone mineral content and bone turnover markers, sex hormones and calciotropic hormones in pre- and early pubertal children (PPTX 35 kb)

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Zürcher, S.J., Borter, N., Kränzlin, M. et al. Relationship between bone mineral content and bone turnover markers, sex hormones and calciotropic hormones in pre- and early pubertal children. Osteoporos Int 31, 335–349 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-019-05180-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-019-05180-7