1. Introduction

Dietary restriction (DR), which is the reduction of calorie intake without malnutrition, has been reported to extend lifespan from yeast to primates (Fontana & Partridge, Reference Fontana and Partridge2015). It is also involved in protecting against age-related diseases in mice (Fontana et al., Reference Fontana, Partridge and Longo2010), reducing the mortality rate in primates (Colman et al., Reference Colman, Beasley, Kemnitz, Johnson, Weindruch and Anderson2014) and even in delaying the physiological changes that come with aging in humans (Cava & Fontana, Reference Cava and Fontana2013). While the molecular mechanisms have been investigated for decades, the precise architecture remains elusive.

Epigenetic modifications are important regulators of transcription networks. DNA methylation is influenced by the environment including dietary intervention. Dietary interventions, including starvation and protein deprivation, can alter DNA methylation patterns with aging (Zampieri et al., Reference Zampieri, Ciccarone, Calabrese, Franceschi, Bürkle and Caiafa2015; Kim et al., Reference Kim, Lee, Choi, An, Jeong, Park, Kim, Yu, Bhak and Chung2016), and DR has been reported to protect global hypomethylation during aging, thereby delaying age-related changes (Hahn et al., Reference Hahn, Grönke, Stubbs, Ficz, Hendrich, Krueger, Andrews, Zhang, Wakelam and Beyer2017; Mattocks et al., Reference Mattocks, Mentch, Shneyder, Ables, Sun, Richie, Locasale and Nichenametla2017).

In this study, we asked two questions: first, whether DNA methylation exists in adult Drosophila; and, second, is DNA methylation affected by DR (Urieli-Shoval et al., Reference Urieli-Shoval, Gruenbaum, Sedat and Razin1982; Lyko et al., Reference Lyko, Ramsahoye and Jaenisch2000; Bird, Reference Bird2002; Dunwell et al., Reference Dunwell, McGuffin, Dunwell and Pfeifer2013; Panikar et al., Reference Panikar, Paingankar, Deshmukh, Abhyankar and Deobagkar2017). We used whole genome bisulfite sequencing (BS-seq) to characterize DNA methylomes in adult Drosophila upon DR and control (unrestricted food) conditions. Our results revealed that a low level of DNA methylation exists in the adult Drosophila genome, but there is no significant difference in DNA methylation level upon DR compared to an unrestricted diet. This suggests that the other epigenetic modifications might underpin DR effects in Drosophila.

2. Materials and methods

(i) Fly food and husbandry

DR and fully fed control medium were prepared in accordance with a previous report (Bass et al., Reference Bass, Grandison, Wong, Martinez, Partridge and Piper2007). The wild-type Dahomey strain was reared under standard laboratory husbandry conditions. Adult female flies were divided into two groups, which were fed with DR medium and fully fed medium. Flies were reared at 25 °C on a 12 h light:12 h dark cycle, at a constant humidity of 65%.

(ii) Sample collection

A total of 80 flies were collected from the DR and fully fed groups at the age of 7 days, 20 flies per condition, respectively (two replicates). In order to maintain the biological variability in the samples, 20 female flies in each condition were mixed and used to extract genomic DNA by DNAeasy Blood and Tissue Kit (Qiagen). The quality of the gDNA was monitored on agarose gels, and DNA purity was checked using the NanoPhotometer® spectrophotometer (IMPLEN). DNA concentration was measured using Qubit® DNA Assay Kit in Qubit 2.0 Fluorimeter (Life Technologies). To assess the efficiency of bisulfite conversion, lambda phage sequence was added to the sample. Ten flies from both DR and fully fed groups were collected at the age of 7 days and flash-frozen for RNA isolation.

(iii) Sequencing of bisulfite-converted DNA libraries

Library construction, bisulfite conversion and sequencing were performed at Beijing Novogene, China, using Illumina Hiseq 2500 platform, following standard protocols.

Clean reads were processed and filtered to remove adaptor sequences, sequences with larger than 10% of Ns, duplicate sequences, contamination and low-quality reads using BGI in-house pipeline. For methylation analysis, we performed alignments of bisulfite-treated reads to the reference genome (Drosophila melanogaster, version BDGP5.23, downloaded from ftp:/ftp.ensemblgenomes.org/pub/release-23/metazoa/fasta/drosophila_melanogaster/dna/) using the Bismark package (version 0.12.5) with default parameters (Krueger & Andrews, Reference Krueger and Andrews2011). The reference genome was first transformed into a bisulfite-converted version (C-to-T and G-to-A converted) and then indexed using bowtie2 (Langmead & Salzberg, Reference Langmead and Salzberg2012). Sequence reads were also transformed into fully bisulfite-converted versions (C-to-T and G-to-A converted) before they were aligned to similarly converted versions of the genome in a directional manner. Only uniquely mapped reads were considered for analysis. From these data, we determined the converted and unconverted cytosines at each position in the D. melanogaster genome assembly, accounting for the fact that each read comes from a bisulfite reaction on one or the other strand. To estimate the overall rate of bisulfite conversion in unmethylated bases in our experiments, we used the C-to-T conversion rate in the lambda phage DNA, in which all cytosines should have been converted. We found that 99.72% (DR) and 99.70% (fully fed) of cytosines were converted in the lambda DNA. At the same time, Q20 and Q30 values were also calculated: Q20 and Q30 are phred scores representing the correct recognition rate of bases to be over 99% and 99.9%, respectively.

To identify the individual cytosines that were methylated, we compared the number of converted and unconverted bases at each cytosine site. To identify the methylation site, we modelled the sum of methylated counts as a binomial (Bin) random variable with the methylation rate,

![]() ${\bf r}_{{\rm i},{\rm j}}$

,

${\bf r}_{{\rm i},{\rm j}}$

,

![]() ${\bf s}_{{\rm i},{\rm j}}^ + {\rm \sim Bin(}{\bf s}_{{\rm i},{\rm j}}^ + + {\bf s}_{{\rm i},{\rm j}}^ - , \,{\bf r}_{{\rm i},{\rm j}})$

, and employed a sliding-window approach, which is conceptually similar to approaches that have been used for bulk whole genome bisulfite sequencing (http://www.bioconductor.org/packages/2.13/bioc/html/bsseq.html). With window size w = 3000 bp and step size 600 bp (Smallwood et al., Reference Smallwood, Lee, Angermueller, Krueger, Saadeh, Peat, Andrews, Stegle, Reik and Kelsey2014), the sum of methylated and unmethylated read counts in each window were calculated. Methylation level (ML) for each cytosine (C) site shows the fraction of methylated Cs, and is defined as:

${\bf s}_{{\rm i},{\rm j}}^ + {\rm \sim Bin(}{\bf s}_{{\rm i},{\rm j}}^ + + {\bf s}_{{\rm i},{\rm j}}^ - , \,{\bf r}_{{\rm i},{\rm j}})$

, and employed a sliding-window approach, which is conceptually similar to approaches that have been used for bulk whole genome bisulfite sequencing (http://www.bioconductor.org/packages/2.13/bioc/html/bsseq.html). With window size w = 3000 bp and step size 600 bp (Smallwood et al., Reference Smallwood, Lee, Angermueller, Krueger, Saadeh, Peat, Andrews, Stegle, Reik and Kelsey2014), the sum of methylated and unmethylated read counts in each window were calculated. Methylation level (ML) for each cytosine (C) site shows the fraction of methylated Cs, and is defined as:

![]() ${\rm ML}\left( {\rm C} \right){\rm } = \textstyle{{{\bf reads}({\bf mC})} \over {{\bf reads}({\bf mC}) + {\bf reads}({\bf C})}}$

, calculated ML was further corrected with the bisulfite non-conversion rate according to a previous study (Lister et al., Reference Lister, Mukamel, Nery, Urich, Puddifoot, Johnson, Lucero, Huang, Dwork and Schultz2013). Given the bisulfite non-conversion rate r, the corrected ML was estimated as:

${\rm ML}\left( {\rm C} \right){\rm } = \textstyle{{{\bf reads}({\bf mC})} \over {{\bf reads}({\bf mC}) + {\bf reads}({\bf C})}}$

, calculated ML was further corrected with the bisulfite non-conversion rate according to a previous study (Lister et al., Reference Lister, Mukamel, Nery, Urich, Puddifoot, Johnson, Lucero, Huang, Dwork and Schultz2013). Given the bisulfite non-conversion rate r, the corrected ML was estimated as:

![]() ${\rm \;} {\bi M}{\bi L}_{{\bf corrected}} = {{{\bi ML} - {\bf r}} \over {1 - {\bf r}}}$

.

${\rm \;} {\bi M}{\bi L}_{{\bf corrected}} = {{{\bi ML} - {\bf r}} \over {1 - {\bf r}}}$

.

To identify genes with different methylation levels between the two conditions, we first identified differentially methylated regions (DMRs) using the swDMR software package (Wang et al., Reference Wang, Li, Jiang, Shao, Liu, Chen and Huang2015). To identify candidate genes and pathways related to these DMRs, GO (Young et al., Reference Young, Wakefield, Smyth and Oshlack2010) and KEGG (Kanehisa et al., Reference Kanehisa, Araki, Goto, Hattori, Hirakawa, Itoh, Katayama, Kawashima, Okuda and Tokimatsu2007) enrichment analyses were conducted.

(iv) cDNA synthesis and q-PCR

Total RNA was extracted using an RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen) from the mixed population of flies under DR and fully fed conditions. RNase-free DNase I (TaKaRa) was used to remove genomic DNA from the RNA samples. The quality and integrity of RNA was assessed using NanoDrop™ 2000 Spectrophotometers (Thermo). cDNA was synthesized using PrimeScript RT Master Mix (TaKaRa). Quantitative real-time PCR (q-PCR) was performed using SYBR Premix Ex Taq (TaKaRa) using a CFX96 Real-Time PCR Detection System (Bio-Rad). The primers used for q-PCR are listed in Table S1. All measurements were performed in parallel with a negative control (no cDNA template), and each RNA sample was analyzed in triplicate. Drosophila Act5C was used as an endogenous control gene. Relative expression level was calculated with 2−ΔΔCt method (Livak & Schmittgen, Reference Livak and Schmittgen2001).

(v) Statistical analysis

For DMR identification we used Fisher's test with a significance threshold level for false discovery rate (FDR) of 5%. For all the q-PCR results, student's t test was used for calculating the significance level. The p-value significance thresholds were as follows: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

(vi) Data availability

Sequencing data generated for this study have been deposited in the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA) as PRJNA318935 (SRP073522).

3. Results

(i) Low level cytosine methylation exists in the adult Drosophila genome

DR can extend Drosophila lifespan (11.9% in median lifespan) compared to fully fed control flies (Fig S1). To test if DNA methylation is associated with this difference in lifespan, we used whole genome bisulfite sequencing to measure it. A total of 7.98 and 8.46 million clean reads (after appropriate quality checks) were obtained from DR and fully fed flies, respectively, yielding a total sequence output of 22.81 Giga bases (11.12 Gb for DR flies, 11.69 Gb for fully fed flies) and accounting for a combined 34.69× (DR flies) and 36.79× (fully fed flies) coverage of the 143.73 Mb fly genome. To estimate the overall rate of bisulfite conversion of unmethylated bases, C-to-T conversion rate of lambda phage DNA was used. It was identified that 99.72 (DR flies) and 99.70% (fully fed flies) of cytosines were converted in the lambda DNA, indicating a very low false negative rate. A total of 63.74 and 65.09% clean reads were mapped to unique D. melanogaster genome regions in DR and fully fed flies, respectively (Table S2), where more than 80% of methylated sites were covered by five or more reads (Fig S2). The percentage of methylation in each condition was almost identical, which is mCGs 0.27 and 0.28, mCHGs 0.26 and 0.28, and mCHHs 0.28 and 0.29 in DR and fully fed flies, respectively (Table S2). This indicates that only a small proportion of the cytosines were methylated, with a higher proportion of methylated cytosines occurring at CHH sites (Fig 1a ). In addition, the CpT dinucleotide site was most often methylated near mCHH sites in both groups (Fig 1b ).

Fig. 1. DNA methylation pattern between DR and fully fed flies. (a) Fraction of mCs identified in each methylation context. (b) Sequence characteristics of 9 bp near mCHH sites, the first and second base after methylated cytosines are indicated by numbers.

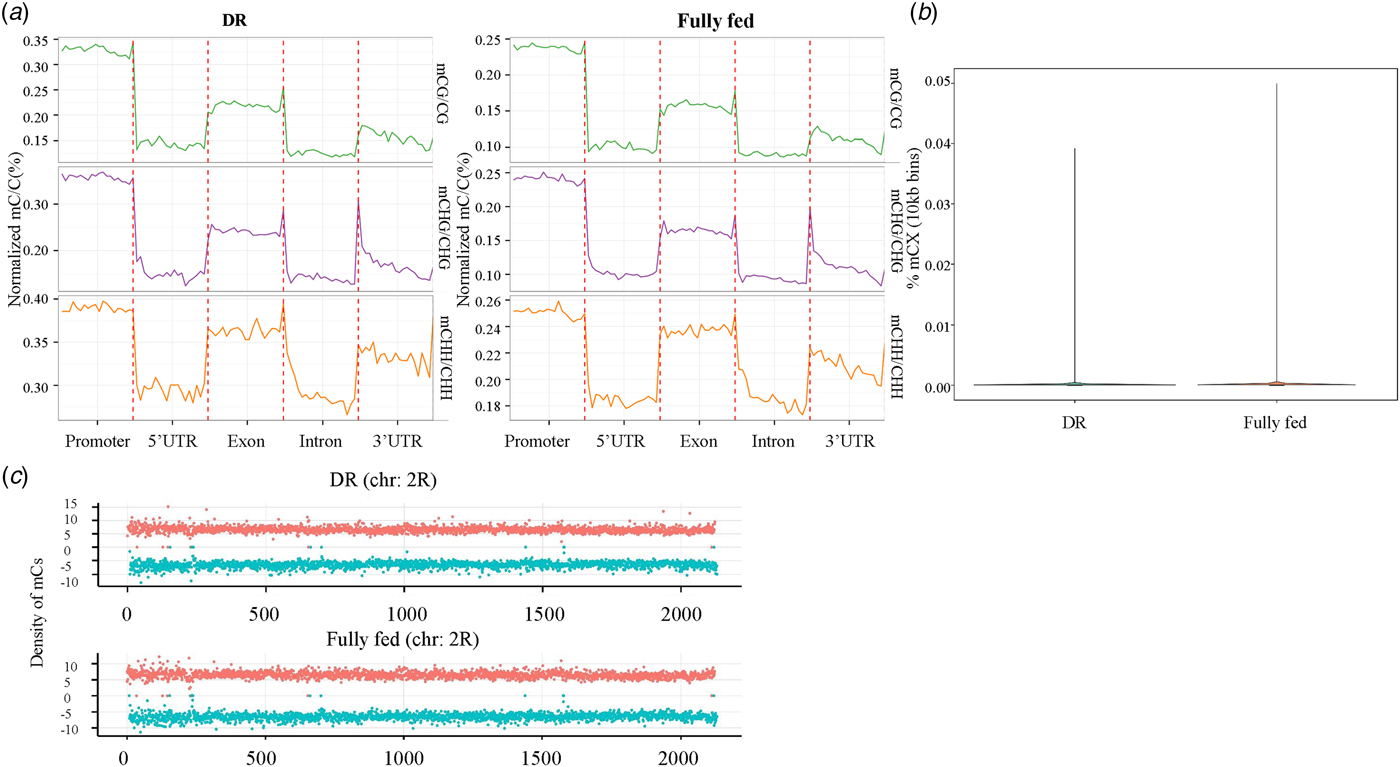

(ii) No significant difference in cytosine methylation level between DR and fully fed flies genome

To quantify the extent of methylation of genomic features, we calculated the cytosine methylation density across the entire genome and in different genomic elements. Results showed that cytosine methylation exhibited a mosaic distribution; the methylation extent was highest in gene promoters (Fig 2a ); and there was no significant difference between methylation levels in DR and fully fed conditions (Fig 2b ). Cytosine methylation fluctuated dramatically across the genome and the cytosine methylation density on the two DNA strands was roughly symmetrical (Fig 2c ). Furthermore, a 54 bp length DMR was identified (with a Benjamin–Hochberg corrected p-value < 0.01, FDR < 0.05) by swDMR. Although we could not find any genes located in this DMR, it was noticed that within the DMR, the DR group showed a significantly lower cytosine methylation than the fully fed control group (Table S3).

Fig. 2. The distribution of DNA methylation in chromosomes and genomic features in DR and fully fed flies. (a) The average cytosine methylation density for each context within each genomic element. Each genomic element was divided into 20-bins. (b) Cytosine methylation density distribution across entire genome. (c) Density of mCs identified on the two DNA strands for chromosome 2R. Density was calculated in 10-kb bins. Red dot indicates ‘+’ strand (Watson), green dot indicates ‘-’ strand (Crick).

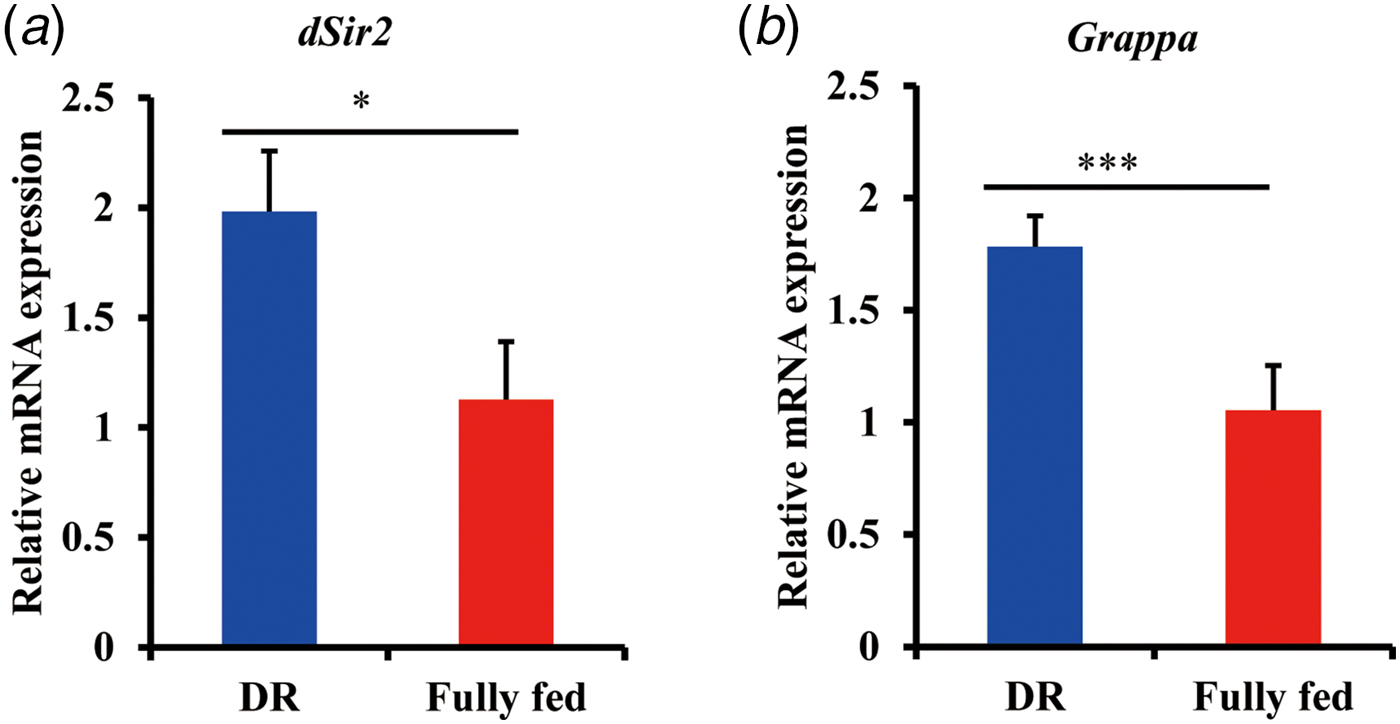

(iii) Other epigenetic modifications are involved in the DR benefits

In order to identify possible factors mediating DR benefits apart from DNA methylation, we analysed two genes which are involved in the histone modifications, dSir2 and Grappa (Rogina & Helfand, Reference Rogina and Helfand2004; Shanower et al., Reference Shanower, Muller, Blanton, Honti, Gyurkovics and Schedl2005). Both these genes were known to be involved in lifespan regulation (List et al., Reference List, Togawa, Tsuda, Matsuo, Elard and Aigaki2009). Based on q-PCR results, we observed a significant increase of mRNA expression in both genes upon DR (Fig 3). As reported in a previous study, the increased level of of dSir2 mRNA is concomitant with histone levels upon DR (Feser et al., Reference Feser, Truong, Das, Carson, Kieft, Harkness and Tyler2010). Also, a positive correlation is reported between methylation of the lysine 79 residue of H3 and mRNA level of Grappa (Shanower et al., Reference Shanower, Muller, Blanton, Honti, Gyurkovics and Schedl2005). Taken together, these data suggest that histone modifications might be involved in mediating the adult fly's longevity in response to DR.

Fig. 3. Analysis of relative mRNA expression of dSir2 (a) and Grappa (b) by q-PCR in DR and fully fed flies. Flies (n = 10) were sampled at the age of 7 days and total RNA was extracted in triplicates. Bar indicates mean ± s.e.m. compared using student's t test. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

4. Discussion

DR extends lifespan in diverse organisms, and a handful of molecular mechanisms have been implicated. However, the involvement of epigenetic mechanisms has just begun to be explored. Here, we first characterized the methylome of adult Drosophila upon DR compared with a fully fed control diet. We found very low cytosine methylation levels and a mosaic distribution pattern in the adult Drosophila genome. CG, CHG and CHH co-exist in the genome, which is consistent with other invertebrates (Bonasio et al., Reference Bonasio, Li, Lian, Mutti, Jin, Zhao, Zhang, Wen, Xiang and Ding2012; Beeler et al., Reference Beeler, Wong, Zheng, Bush, Remnant, Oldroyd and Drewell2014; Drewell et al., Reference Drewell, Bush, Remnant, Wong, Beeler, Stringham, Lim and Oldroyd2014). Furthermore, we also found rare cytosine methylations in UTR regions and in snRNA, miRNA, ncRNA, snoRNA, rRNA and pseudogene loci as observed in ants (Bonasio et al., Reference Bonasio, Li, Lian, Mutti, Jin, Zhao, Zhang, Wen, Xiang and Ding2012). We did not detect evidence of significant methylation in annotated transposable elements or in other repeat sequences in D. melanogaster (as with Nasonia vitripennis; Beeler et al., Reference Beeler, Wong, Zheng, Bush, Remnant, Oldroyd and Drewell2014).

The contribution of epigenetic mechanisms, especially cytosine methylation to complex phenotypes is not direct, and has only just begun to be studied. Based on our data, no significant epigenetic differences are observed during DR and fully fed conditions despite the comparably higher sequencing coverage and mapping rate used in our study (Table S4). However, we note that the high similarities of cytosine methylation patterns between DR and fully fed conditions may be due to the retention of some cytosine methylation marks under the diet effect (Beeler et al., Reference Beeler, Wong, Zheng, Bush, Remnant, Oldroyd and Drewell2014). We should not exclude the possible involvement of epigenetic mechanisms in diet-induced lifespan extension. For example, in the social insect honeybee, female larval development into the queen with longer lifespan or worker bee with its shorter lifespan is determined by diet and has associated DNA methylation changes (Ford, Reference Ford2013). Histone modification is also likely to be involved in DR-induced longevity. Both grappa and dsir2 have been considered to be histone modifiers required for lifespan extension (List et al., Reference List, Togawa, Tsuda, Matsuo, Elard and Aigaki2009; Slade & Staveley, Reference Slade and Staveley2016), but the exact effects of cytosine methylation, gene regulation and diet-induced longevity need further exploration.

The authors thank Professor Douglas Armstrong for his comments on and corrections to the manuscript. The authors also thank the technical support from Novogene-Beijing in China. This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31771338) and the ‘Thousand Talents Program’ in Sichuan (000433).

Declaration of interest

None.

Supplementary material

The online supplementary material can be found available at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0016672317000064.