Abstract

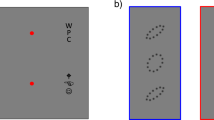

It is now emerging that vision is usually limited by object spacing rather than size. The visual system recognizes an object by detecting and then combining its features. 'Crowding' occurs when objects are too close together and features from several objects are combined into a jumbled percept. Here, we review the explosion of studies on crowding—in grating discrimination, letter and face recognition, visual search, selective attention, and reading—and find a universal principle, the Bouma law. The critical spacing required to prevent crowding is equal for all objects, although the effect is weaker between dissimilar objects. Furthermore, critical spacing at the cortex is independent of object position, and critical spacing at the visual field is proportional to object distance from fixation. The region where object spacing exceeds critical spacing is the 'uncrowded window'. Observers cannot recognize objects outside of this window and its size limits the speed of reading and search.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$209.00 per year

only $17.42 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Change history

13 November 2008

In the version of this article initially published, the legend to Figure 5 contained several errors. The second sentence should read “Fixating on the red minus, you will be unable to identify the middle object in the first eight rows unless you isolate it by hiding the flanking objects with your fingers (or two pencils). ” The fourth sentence should read “Grating patches, similar to those in the top row, are often taken to be one-feature objects. ” These errors have been corrected in the HTML and PDF versions of the article.

References

Barlow, H.B. Summation and inhibition in the frog's retina. J. Physiol. (Lond.) 119, 69–88 (1953).

Robson, J.G. & Graham, N. Probability summation and regional variation in contrast sensitivity across the visual field. Vision Res. 21, 409–418 (1981).

Treisman, A.M. & Gelade, G. A feature-integration theory of attention. Cognit. Psychol. 12, 97–136 (1980).

Pelli, D.G., Burns, C.W., Farell, B. & Moore-Page, D.C. Feature detection and letter identification. Vision Res. 46, 4646–4674 (2006).

Hubel, D.H. & Wiesel, T.N. Receptive fields, binocular interaction and functional architecture in the cat's visual cortex. J. Physiol. (Lond.) 160, 106–154 (1962).

Desimone, R. & Duncan, J. Neural mechanisms of selective visual attention. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 18, 193–222 (1995).

Ullman, S. High-Level Vision: Object Recognition and Visual Cognition (MIT Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 2000).

Parkes, L., Lund, J., Angelucci, A., Solomon, J.A. & Morgan, M. Compulsory averaging of crowded orientation signals in human vision. Nat. Neurosci. 4, 739–744 (2001).

Motter, B.C. Crowding and object integration within the receptive field of V4 neurons. J. Vis. 2:274, 247a (2002).

Ledgeway, T., Hess, R.F. & Geisler, W.S. Grouping local orientation and direction signals to extract spatial contours: empirical tests of “association field” models of contour integration. Vision Res. 45, 2511–2522 (2005).

Intriligator, J. & Cavanagh, P. The spatial resolution of visual attention. Cognit. Psychol. 43, 171–216 (2001).

Biederman, I. Recognition-by-components: a theory of human image understanding. Psychol. Rev. 94, 115–147 (1987).

Tanaka, J.W. & Farah, M.J. Parts and wholes in face recognition. Q. J. Exp. Psychol. A 46, 225–245 (1993).

Martelli, M., Majaj, N.J. & Pelli, D.G. Are faces processed like words? A diagnostic test for recognition by parts. J. Vis. 5, 58–70 (2005).

Geisler, W. & Murray, R. Cognitive neuroscience: practice doesn't make perfect. Nature 423, 696–697 (2003).

Levi, D.M. Crowding - an essential bottleneck for object recognition: a mini-review. Vision Res. 48, 635–354 (2008).

Pelli, D.G., Palomares, M. & Majaj, N.J. Crowding is unlike ordinary masking: distinguishing feature integration from detection. J. Vis. 4, 1136–1169 (2004).

He, S., Cavanagh, P. & Intriligator, J. Attentional resolution and the locus of visual awareness. Nature 383, 334–337 (1996).

Blake, R., Tadin, D., Sobel, K.V., Raissian, T.A. & Chong, S.C. Strength of early visual adaptation depends on visual awareness. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 103, 4783–4788 (2006).

Bouma, H. Interaction effects in parafoveal letter recognition. Nature 226, 177–178 (1970).

Freeman, J. & Pelli, D.G. An escape from crowding. J. Vis. 7, 1–14 (2007).

Reddy, L. & VanRullen, R. Spacing affects some, but not all, visual searches: implications for theories of attention and crowding. J. Vis. 7, 1–17 (2007).

Solomon, J.A. & Morgan, M.J. Stochastic re-calibration: contextual effects on perceived tilt. Proc Biol Sci 273, 2681–2686 (2006).

Bouma, H. Visual interference in the parafoveal recognition of initial and final letters of words. Vision Res. 13, 767–782 (1973).

Bex, P.J., Dakin, S.C. & Simmers, A.J. The shape and size of crowding for moving targets. Vision Res. 43, 2895–2904 (2003).

van den Berg, R., Roerdink, J.B.T.M. & Cornelissen, F.W. On the generality of crowding: visual crowding in size, saturation and hue compared to orientation. J. Vis. 7, 1–11 (2007).

Chung, S.T.L., Li, R.W. & Levi, D.M. Crowding between first- and second-order letter stimuli in normal foveal and peripheral vision. J. Vis. 7, 1–13 (2007).

Pelli, D.G. et al. Crowding and eccentricity determine reading rate. J. Vis. 7, 1–36 (2007).

Huey, E.B. The Psychology and Pedagogy of Reading (Macmillan, New York, 1908).

Legge, G.E., Pelli, D.G., Rubin, G.S. & Schleske, M.M. Psychophysics of reading. I. Normal vision. Vision Res. 25, 239–252 (1985).

Levi, D.M., Song, S. & Pelli, D.G. Amblyopic reading is crowded. J. Vis. 7, 1–17 (2007).

Vlaskamp, B.N., Over, E.A. & Hooge, I.T. Saccadic search performance: the effect of element spacing. Exp. Brain Res. 167, 246–259 (2005).

Woodworth, R.S. Experimental Psychology (Holt, New York, 1938).

Bouma, H. Visual search and reading: eye movements and functional visual field: a tutorial review. in Attention and Performance VII (Requin, J.) (Erlbaum, Hillsdale, New Jersey, 1978).

Bosse, M.L., Tainturier, M.J. & Valdois, S. Developmental dyslexia: the visual attention span deficit hypothesis. Cognition 104, 198–230 (2007).

McConkie, G.W. & Rayner, K. The span of the effective stimulus during a fixation in reading. Percept. Psychophys. 17, 578–586 (1975).

Engbert, R., Nuthmann, A., Richter, E.M. & Kliegl, R. SWIFT: a dynamical model of saccade generation during reading. Psychol. Rev. 112, 777–813 (2005).

O'Regan, J.K. Eye movements and reading. Rev. Oculomot. Res. 4, 395–453 (1990).

Legge, G.E. Psychophysics of Reading in Normal and Low Vision (Erlbaum, Mahwah, New Jersey, 2007).

Motter, B.C. & Simoni, D.A. The roles of cortical image separation and size in active visual search performance. J. Vis. 7, 1–15 (2007).

Stanovich, K.E., Siegel, L.S. & Gottardo, A. Converging evidence for phonological and surface subtypes of reading disability. J. Educ. Psychol. 89, 114–127 (1997).

Bouma, H. & Legein, C.P. Foveal and parafoveal recognition of letters and words by dyslexics and by average readers. Neuropsychologia 15, 69–80 (1977).

Prado, C., Dubois, M. & Valdois, S. The eye movements of dyslexic children during reading and visual search: impact of the visual attention span. Vision Res. 47, 2521–2530 (2007).

Kwon, M., Legge, G.E. & Dubbels, B.R. Developmental changes in the visual span for reading. Vision Res. 47, 2889–2900 (2007).

Lévy-Schoen, A. Exploration et connaissance de l'espace visuel sans vision périphérique. Trav. Hum. 39, 63–72 (1976).

Chung, S.T.L., Levi, D.M. & Legge, G.E. Spatial-frequency and contrast properties of crowding. Vision Res. 41, 1833–1850 (2001).

Toet, A. & Levi, D.M. The two-dimensional shape of spatial interaction zones in the parafovea. Vision Res. 32, 1349–1357 (1992).

Taylor, S.E. Eye movements in reading: facts and fallacies. Am. Ed. Res. J. 2, 187–202 (1965).

Valdois, S. et al. Phonological and visual processing deficits can dissociate in developmental dyslexia: evidence from two case studies. Read. Writing 16, 541–572 (2003).

Martelli, M., Di Filippo, G., Spinelli, D. & Zoccolotti, P. Crowding, reading and developmental dyslexia. Perception 35, supp 174 (2006).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Supplementary information

Supplementary Text and Figures

Supplementary Figures 1–5, Supplementary Discussion and Supplementary Note (PDF 435 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Pelli, D., Tillman, K. The uncrowded window of object recognition. Nat Neurosci 11, 1129–1135 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1038/nn.2187

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/nn.2187

This article is cited by

-

The effects of distractors on brightness perception based on a spiking network

Scientific Reports (2023)

-

Extended perceptive field revealed in humans with binocular fusion disorders

Scientific Reports (2023)

-

Abnormal basic visual processing functions in binocular fusion disorders

Scientific Reports (2023)

-

Effects of syllable boundaries in Tibetan reading

Scientific Reports (2023)

-

Coupling perception to action through incidental sensory consequences of motor behaviour

Nature Reviews Psychology (2022)