Abstract

This work presents an evaluation of batch, fed-batch, and sequential batch cultivation techniques for production of R. marinus DSM 16675 and its exopolysaccharides (EPSs) and carotenoids in a bioreactor, using lysogeny broth (LB) and marine broth (MB), respectively, in both cases supplemented with 10 g/L maltose. Batch cultivation using LB supplemented with maltose (LBmalt) resulted in higher cell density (OD620 = 6.6) than use of MBmalt (OD620 = 1.7). Sequential batch cultivation increased the cell density threefold (OD620 = 20) in LBmalt and eightfold (OD620 = 14) in MBmalt. In both single and sequential batches, the production of carotenoids and EPSs using LBmalt was detected in the exponential phase and stationary phase, respectively, while in MBmalt formation of both products was detectable in both the exponential and stationary phases of the culture. Heteropolymeric EPSs were produced with an overall volumetric productivity (QE) of 0.67 (mg/L h) in MBmalt and the polymer contained xylose. In LB, QE was lower (0.1 mg/L h) and xylose could not be detected in the composition of the produced EPSs. In conclusion, this study showed the importance of a process design and medium source for production of R. marinus DSM 16675 and its metabolites.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Rhodothermus marinus is a thermophilic aerobic heterotrophic bacterium that was first isolated from a submarine hot spring in Isafjardardjup in Iceland (Alfredsson et al. 1988). At first, R. marinus was primarily of interest because of its thermostable enzymes (Crennell et al. 2002; Hobel et al. 2005; Karlsson et al. 2002; Nordberg Karlsson et al. 1997; Spilliaert et al. 1994). More recently, strain R. marinus DSM 16675 (previously published as strain PRI493 and MAT493) has been a target for research due to the developed genetic tools, enabling genetic engineering for the first time in the genus (Bjornsdottir et al. 2011). Moreover, both wild-type and engineered strains of R. marinus have been used to study two different groups of natural products, i.e., exopolysaccharides (EPSs) (Sardari et al. 2017) and carotenoids (Ron et al. 2018). Marine exopolysaccharides have unique properties which enable them to have potential applications in different industries such as food and pharmaceutical industries (Nwodo et al. 2012). Likewise, microbial carotenoids have a wide range of applications especially in food and medical industries (Kaiser et al. 2007).

During the study of the natural products of R. marinus, it became apparent that there is a lack of knowledge on cultivation technology for reaching high cell density of R. marinus, which is a necessity to increase the yield and productivity of the products. Only a handful of studies have published growth data on R. marinus. In most cases, these studies have focused on increasing the production of specific carbohydrate-converting enzymes, including xylanolytic enzymes (Dahlberg et al. 1993), β-mannanase (Gomes and Steiner 1998), α-l-arabinofuranosidase (Gomes et al. 2000), α-galactosidase (Blücher et al. 2000), amylase and pullulanase (Gomes et al. 2003), in all cases using batch cultivation at low cell densities. Recently, 13C flux was also reported for the type strain of R. marinus (DSM4252), but also in this case very low cell densities (OD < 2) were reached (Cordova et al. 2017). The aim of this study was to evaluate the different cultivation techniques and media to obtain higher cell densities of R. marinus DSM 16675 and to investigate the metabolite formation kinetics.

Materials and methods

Chemicals

Yeast extract and tryptone were obtained from Duchefa Biochemie, Marine Broth 2216-Difco from Becton Dickinson and NaOH (50%) from Merck. All other chemicals were from Sigma-Aldrich.

Microorganism and inoculum preparation

Rhodothermus marinus DSM 16675 (also known as MAT/PRI 493) was received from Matís ohf, Reykjavík, Iceland. The cells were revived on solid agar plates with modified Thermus 162 medium with 1% NaCl at 65 °C for 24–48 h according to DSMZ specifications (Degryse et al. 1978). Colonies were transferred to 5 mL of liquid medium [Lysogeny broth (LB) including 10 g/L tryptone, 10 g/L NaCl, and 5 g/L yeast extract, or marine broth (MB) (according to DSMZ specifications)] in 50 mL falcon tubes for incubation (Ecotron, Infors) at 65 °C and 200 rpm for 24 h. After the overnight incubation, the cells were transferred into 50 mL of liquid medium in a 500 mL baffled shake flask and incubated for 8 h (OD620nm ≈ 5 for LB and OD620nm ≈ 1.5 for MB) before inoculating the bioreactor (Multifors 2, Infors). All cultivations were done using 10% (v/v) inoculum grown in liquid medium.

Culture media preparation

LB supplemented with 10 g/L glucose (LBglu) or maltose (LBmalt), and MB supplemented with maltose (MBmalt) were used in the different cultivations. The liquid medium was prepared and autoclaved at 121 °C for 20 min. A stock solution of sugar with a concentration of 100 g/L was prepared and filter sterilized and added to the culture medium to reach the final concentration of 10 g/L.

Cultivation conditions in stirred tank bioreactor

Batch cultivation

Batch cultivation was performed in a 1 L stirred tank bioreactor (Multifors 2, Infors) with a working volume of 0.5 L. The temperature was set at 65 °C and the pH of the medium in the bioreactor was maintained at 7.0 by addition of 1 M NaOH. The bioreactor was aerated with filter-sterilized air at a constant rate of 0.5 VVM (air volume/culture volume/min). The initial agitation speed was 200 rpm and cascaded with a dissolved oxygen tension (DOT) probe. The DOT was maintained at setpoint of 40% by the DOT probe (instructing the bioreactor engine to increase the agitation). The percentage of CO2 in the outgas was measured online by a gas analyzer (Gas analyzer, Infors). The antifoam (Y-30) was used during the cultivation to suppress foam formation. The antifoam was diluted 50 times before use since the concentrated antifoam was toxic for cells. Samples were taken during 24 h of cultivation and the OD of each sample was measured at 620 nm.

Fed-batch cultivation

The fed-batch cultivation of R. marinus DSM 16675 was started in normal batch mode. After inoculation, the batch was started with 350 ml of the LB medium supplemented with 5 g/L maltose and the OD was monitored every 2 h. When the growth rate decreased and the OD was almost constant, meaning the cells reached stationary phase, the fed-batch mode was initiated by addition of the feed solution. Stepwise feeding was used and a concentrated feed was prepared with equivalent ingredient proportions (100 g/L maltose, 100 g/L yeast extract, 200 g/L tryptone, and 10 g/L NaCl) and added to the bioreactor using a syringe. The salinity of the medium should remain constant during the fed-batch, hence the salt concentration was unchanged in the feed. The volume fed to the bioreactor was calculated based on the carbohydrate already consumed at the time of feeding, so that it would reconstitute the concentration of sugar. Samples were taken and the OD of each sample was measured at 620 nm.

Sequential batch cultivation with cell recycling

Two sequential batch cultivations of R. marinus DSM 16675 were carried out. The first one used LBmalt with a total of seven consecutive batches with cell recycling and the second used MBmalt in four consecutive batches. The first batch cultivation was inoculated with 50 ml of inoculum (10% v/v) to 450 ml of the medium in the bioreactor. The OD measurement was performed every 1 or 2 h for each batch and when the cells in each batch reached the stationary phase, the cultivation was terminated and the medium containing cells was transferred to 250 mL sterile centrifuge tubes and pelleted at 7000 rpm and 20 °C for 10 min. The supernatant was discarded while the pellet was dissolved in 500 ml of pre-heated (65 °C) fresh medium and transferred to the bioreactor. This process was repeated and the samples were taken until termination of the cultivation.

Analytical methods

Samples were taken with regular intervals during the cultivation, and used for determining cell growth (spectrophotometrically as optical density (OD) at 620 nm), substrate consumption, organic acid determination, and spectrophotometric estimation of carotenoids.

EPSs and substrate analysis and quantification

Total produced EPSs were determined by quantifying their total monosaccharide content after acid hydrolysis. Samples from the cultivation were centrifuged and the crude EPSs were precipitated with four volumes of ethanol (99%) from the cell-free supernatant and lyophilized. The monosaccharides were analyzed after hydrolysis of lyophilized crude EPSs with sulfuric acid, neutralization with 0.1 M Ba (OH)2, and subsequently proper dilution of the samples (Sluiter et al. 2008). Substrate consumption and monosaccharide content of the produced exopolysaccharides (EPSs) were determined by high-performance anion-exchange chromatography (HPAEC) (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, USA) using a Dionex CarboPac PA-20 analytical column which was coupled to a Dionex CarboPac PA-20 guard column. Three pumps were used for three different eluents: Pump A (Milli-Q water), pump B (2 mM NaOH), and pump C (200 mM NaOH). Separation occurred during 23 min of running time using a mixture of A (62.5%) and B (37.5%) with an isocratic flow of 0.5 mL/min and after that the column was regenerated with C (100%) for 2 min at the same flow rate. Disaccharide analysis was carried out using a mixture of A (50%) and C (50%) with an isocratic flow of 0.5 mL/min and the running time was 20 min. The analytes were detected with an ED40 electro-chemical detector. Before injection in the Dionex system, the cell-free supernatant was filtered through a 0.2 µm polypropylene filter after proper dilution and analyzed for the remaining substrate in each sample.

The total volumetric productivity of produced EPSs (QE) was calculated as the sum of QE in each batch, as follows:

The n and t indicate the number of batches and total time (h) of the sequential batch cultivation, respectively, and \(\Delta P_{i}\) is the EPS formation during each single batch i. The QE of each batch was calculated as \(\Delta P\) divided by the time of each batch.

Carotenoids analysis

The carotenoids were extracted from the R. marinus DSM 16675 strain during batch, fed-batch, and sequential batch cultivations. The extraction was performed according to the method described by Biehler et al. (Biehler et al. 2010). One milliliter of culture sample was pelleted down at 13,000 rpm for 5 min and the pellet was re-suspended in 1 mL of acetone (99.5%), shaken for 1 h on a rocking table at room temperature and then, separated from the supernatant by centrifugation at 13,000 rpm for 3 min. The absorbance of the cell-free supernatant was measured at 450 nm using a UV quartz cuvette (Hellma) in a UV/Visible spectrophotometer (Pharmacia biotech, Ultrospec 1000) and plotted against the cultivation time.

Organic acid analysis

Organic acid determination was performed using high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC). After proper dilution, 1 mL of a cell-free sample was acidified with 20 µL of sulfuric acid (20% v/v), and filtered through 0.2 µm polypropylene filter, prior to analysis in the HPLC system (HPLC Ultimate-3000 RSLC, Dionex) connected to an IR detector (Shodex, RI-101). Separation of organic acid was done using the analytical column Aminex HPX-87H connected to a guard column (Biorad, Richmond, CA, USA). The temperature was set at 40 °C and the mobile phase consisted of 5 mM H2SO4 with a flow rate of 0.5 mL/min.

Results and discussion

Single batch cultivation of R. marinus DSM 16675

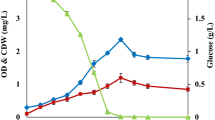

A previous study, focusing on shake flask cultivations in marine broth (MB) supplemented with different mono- and disaccharides, showed that the highest growth of R. marinus DSM 16675 (0.75 g/L) was reached using supplementation with maltose (MBmalt) (Sardari et al. 2017). Therefore, in this study, maltose was chosen as a supplementary carbon source and was added to cultivation of R. marinus DSM 16675, run in complex media (LB or MB) using a stirred tank bioreactor with controlled aeration and pH (Fig. 1). Growth of R. marinus DSM 16675 was initiated after a lag phase of 6 and 4 h in LBmalt and MBmalt, respectively, followed by an exponential growth phase lasting until 10 h cultivation time, reaching a maximum specific growth rate (μmax) of 0.42 h−1 and 0.22 h−1 in LBmalt and MBmalt, respectively. After 10 h, the cell culture entered the stationary phase, as monitored by cease of growth. Consumption of maltose in cultivations using LBmalt was detected between 6 and 10 h cultivation time at an exponential rate, which decreased significantly after 10 h. In the MBmalt cultivation, maltose consumption started after 4 h (indicating start of the exponential growth phase) with a fast consumption rate until 10 h, followed by a period with gradually decreasing maltose concentration until the end of cultivation. It should be noted that accumulation of glucose was seen in both media from the start of the exponential phase until the end of the cultivation, meaning that not all of the maltose was taken up and consumed, but rather enzymatically degraded to its monosaccharide constituents (Fig. 1). Moreover, the obtained glucose in LB medium was consumed for 2 h during the stationary phase without display of cell growth and thus might be used for cells’ maintenance (Navarro Llorens et al. 2010). The maximum OD620 in LBmalt was 6.6 after 13 h which was significantly higher than the OD observed in MBmalt where a maximum OD620 of 1.71 was observed after 24 h.

In the previous study (Sardari et al. 2017) with shake flask cultivations, it was shown that glucose supplementation in MB (MBglu) resulted in a slight increase in the cell growth of R. marinus DSM 16675 and EPSs production. Hence, cultivation of R. marinus DSM 16675 was performed to investigate the growth behavior using LB medium supplemented with 10 g/L glucose (LBglu) at controlled aeration and pH in the bioreactor (Fig. 2). A bioreactor cultivation with LB (without supplementation) was also run in parallel. The cultivation data displayed that glucose supplementation had no effect on the cell growth and only low (if any) uptake of glucose could be detected during the experiment. A maximum OD620 of 2.7 was reached after 16 h in the bioreactor cultivation using LBglu, which was less than that of the cultivation using LB with no additional carbon source (OD620 of 3.6 after 16 h).

Product formation kinetics in single batch cultivations

R. marinus DSM 16675 has been shown to form two products of potential application interest: carotenoids (Ron et al. 2017) and exopolysaccharides (Sardari et al. 2017). To increase the understanding of the formation of these products, the relationship between cell growth and the production of carotenoids and EPSs in single batch cultivations in a pH-controlled bioreactor using LBmalt and MBmalt was studied (Fig. 3). It should be noted that LB and MB (except for the added maltose) contain very low concentrations of sugars, as previously reported by Sezonov et al. (Sezonov et al. 2007) which were precipitated and hydrolyzed together with the EPSs from the medium (Fig. 1 and 2, supplementary materials). The reduction in those sugars was observed between 6 and 10 h cultivation in LBmalt (Fig. 3a) and between 2 and 6 h in MBmalt (Fig. 3b).

As seen in Fig. 3a, the batch cultivation in LBmalt produced carotenoids starting 6 h after inoculation and continued until the end of the exponential phase. The total produced carotenoids profile, represented by absorbance at 450 nm and a final absorbance of 0.061, was best fitted to a second-order polynomial equation using Excel software (Microsoft, 2010) in the exponential phase of the cultivation (Fig. 4a). On the other hand, the changes in EPSs concentration were more difficult to evaluate, with apparent formation only seen from the onset of the stationary phase reaching a final net formation of 5.18 mg/L at the end of cultivation.

In MBmalt a different production pattern of carotenoids and EPSs was observed. Figure 3b depicts that production of both total carotenoids and EPSs started at the beginning of the exponential phase and continued during the stationary phase for both products, reaching a total carotenoids final absorbance at 450 nm of 0.048 and a final EPSs formation of 6.28 mg/L. It can be speculated that the increase in EPSs formation during the stationary phase can be a result of quorum sensing activity that consequently stimulates formation of biofilm (Sengupta et al. 2018). In addition, cell lysis can contribute to biofilm development in which the EPSs are the main components (Bayles 2007; Flemming et al. 2007). Bayles (Bayles 2007) described that the DNA released from the cells during cell lysis at the stationary phase is a structural component of the biofilm matrix. However, in our case the rate of cell lysis seems to be low since the OD was not decreased at the stationary phase.

The total produced carotenoids profile, also, was fitted to a second-order polynomial equation for exponential phase and stationary phase of the batch cultivation (Fig. 4b).

The ratio of EPSs to cell growth (OD) was 1.41 and 4.18 for LBmalt and MBmalt, respectively. This indicates a strong competition between cell growth and EPS production as previously described (Sardari et al 2017). In addition, analysis of the monosaccharide composition of the EPSs hydrolysate from the cultivations in both media was performed to quantify the total EPSs. It showed that the monosaccharides of the produced EPSs from LBmalt consisted of arabinose, galactose, glucose, and mannose. For the EPSs in the culture grown in MBmalt the same monosaccharides were found, but with the addition of xylose, which is in accordance with the previously published data on the EPSs composition from R marinus grown in this medium (Sardari et al. 2017) (Fig. 3, supplementary materials).

The cells produced carotenoids in both media, but interestingly, the production of carotenoids continued in the stationary phase when the cells were grown in MBmalt (Fig. 3b). This might be due to accumulation of tricarboxylic acid cycle metabolites with subsequent conversion to other products such as carotenoids (Henke et al. 2017; Tao et al. 2011).

Production of short chain fatty acids (SCFA) was investigated to explain the decrease in pH during the cultivation, and corresponding consumption of NaOH (1 M), approximately 3 mL in LBmalt and 0.5 mL in MBmalt, during the batch cultivations of R. marinus DSM 16675 in both media. However, very little lactic acid, formic acid, and acetic acid were produced. The main reason for the drop in pH might instead be due to the reaction of the produced CO2 with water and formation of carbonic acid in the culture media (Das and Mangwani 2015).

As seen in Fig. 1, both maltose and glucose were left in the culture medium at the end of both cultivations, excluding that the carbon source is the limiting factor for growth. The highest cell densities were reached in the batch cultivations of R. marinus DSM 16675 using LBmalt as growth medium. Hence, LBmalt was selected as growth medium for fed-batch cultivation of R. marinus DSM 16675, aiming at further increasing cell densities, and solve the eventual nutrient limitations occurring towards the end of the batch cultivations.

Fed-batch cultivation of R. marinus DSM 16675

Fed-batch cultivation with stepwise feeding was applied for R. marinus DSM 16675 using LB medium supplemented with 5 g/L of maltose in the bioreactor (Fig. 5).

Growth profile of R. marinus DSM 16675 and sugar consumption during a fed-batch cultivation in LBmalt and b repeated fed-batch cultivation in LBmalt. Symbols: (filled diamond) cell growth represented as OD620nm, and (filled square) maltose concentration (g/L). Feeding was made stepwise, as indicated by arrows

As seen in Fig. 5a, the cell growth reached the stationary phase after 12 h of cultivation at an OD of 6.73 after consumption of approximately 3 g/L maltose. The first feed, which consisted of 20 mL of feed solution, was added at 12.5 h of cultivation and growth resumed. The maximum OD reached was 7.84 after 14 h, which decreased to 6.4 after 1 h. At that point, the second feed was added at 15 h of cultivation, but growth was not recovered. Instead, the OD dropped unexpectedly. The maximum OD achieved in the fed-batch cultivation did not exceed the OD in the prior batch cultivations. This could theoretically be due to substrate inhibition, since the concentration of maltose reached 12.47 g/L after the second feed addition. However, repeated fed-batch cultivations with maltose concentrations never exceeding 5 g/L also reached the stationary phase at the same cell densities (Fig. 5b).

Other potential explanations for the termination of growth at 14 h could be either inhibition due to accumulation of growth-inhibiting metabolites, or quorum sensing. To distinguish between these alternatives, sequential batch cultivation with cell recycling was selected as a method to circumvent metabolites reaching growth-inhibiting levels.

Sequential batch cultivation of R. marinus DSM 16675 with cell recycling

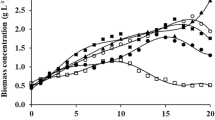

Since the fed-batch cultivations were not successful in increasing biomass concentration, sequential batch cultivation of R. marinus DSM 16675 with cell recycling in LBmalt and MBmalt was investigated (Fig. 6).

The first batch cultivation, of R. marinus DSM 16675, in the cultivation sequence in the respective medium was started with the addition of a 10% (v/v) inoculum followed by an exponential phase with a duration of 5 h (cultivation time 3–8 h), reaching the stationary phase after 9 h of cultivation, and a final OD620nm of 5.68 and 1.82 in LBmalt and MBmalt, respectively (Fig. 6). At that point, the cultivation was stopped and the next batch was prepared with fresh medium and inoculated with the recycled cells from the previous batch. Between batch 4 and batch 5, a drop in the starting cell density was observed (compared to the final cell density of the previous batch cycle). This must be due to loss of cells during handling between the cycles while removing the old medium and adding fresh medium. After seven cycles using LBmalt, the maximum OD of 20.2 was reached after 35 h cultivation time, resulting in a threefold increase relative to that of the batch and fed-batch trials. To the best of our knowledge, the final OD value of 20.2 is the highest cell density achieved with the genus according to literature (Fig. 6a). Our results are comparable with the results obtained with other similar thermophilic bacteria that were cultivated to reach higher cell densities (Table 1). As can be seen, sequential batch with cell recycling is as effective as other fermentation techniques to produce high cell densities with thermophiles.

The maximum OD of 14.32 was reached over four cycles in the MBmalt medium after 30 h of cultivation, which is an eightfold increase relative to that of the batch trial (Fig. 6b).

The higher cell density in LBmalt medium can be due to the higher concentration of yeast extract in LBmalt (5 g/L) compared to that in MBmalt (1 g/L). Yeast extract generates high cell densities for Gram-negative bacteria as described by Gray (Gray et al. 2008). Also, LBmalt has twice as much of tryptone (casein peptone) (10 g/L) as peptone in MBmalt (5 g/L), which can explain the higher cell densities in LBmalt compared to MBmalt Another difference is the salt composition and concentration, which seems to slightly hinder growth of R. marinus DSM 16675 in MBmalt. Marine broth emulates open seawater salt composition and has therefore a higher NaCl (2% (w/v)) concentration compared to LB (1% (w/v)).

In each cultivation cycle, the stationary phase was reached before depletion of maltose, which is in line with results from the prior batch cultivations, most likely due to depletion of other nutrients or accumulation of growth-inhibiting products.

The maximum specific growth rate (μmax) was 0.42 h−1 for the first batch cultivation in LBmalt and 0.26 h−1 for the first batch cultivation in MBmalt, which is in accordance with the specific growth rates observed in the single batch cultivations (described in Sect. 3.1.1). However, the specific growth rate decreased gradually in the later batches until the end of cultivation. This shows that the limitation in growth in the fed-batch (described in Sect. 3.2) may have been caused by accumulation of growth-inhibiting metabolites, alleviated by the change of medium in the sequential batch. However, the reasons for the decreased growth rate, in the later cycles in the batch sequence remain unclear and may be influenced by quorum sensing. Reaching a high cell density in a batch culture is a sign for cells to predict severe competition for nutrients and subsequently lack of nutrients. Entry to the stationary phase is a main solution for bacteria to survive. Therefore, the quorum sensing system (Kaur et al. 2018; Montgomery et al. 2013) regulates the transition into stationary phase by quorum sensing signals which are produced mainly at high cell density (Lazazzera 2000).

Product formation kinetics in the sequential batches

The production of carotenoids and EPSs was evaluated in the sequential batch cultivations of R. marinus DSM 16675 in both LBmalt and MBmalt (Fig. 7).

The production of carotenoids increased as the cell density increased in each batch (Fig. 7). In LBmalt carotenoid production ceased at the end of each cycle, indicating that the stationary phase was reached (Fig. 7a). A corresponding decrease was not observed in MBmalt, in accordance with the production pattern in the single batch. The total carotenoid content in LBmalt increased throughout the complete sequence of batches, as shown by the absorbance at 450 nm from 0.002 at the beginning of the first batch cultivation, to 1.67 at the end of the last batch in the cultivation sequence (Fig. 8a). A similar trend was shown in the batch cultivation sequence of R. marinus DSM 16675 in MBmalt (Fig. 8b). The production of total carotenoids increased with increasing cell density in every batch, which is in accordance with the production trend observed in cultivations using LBmalt. The produced total carotenoids in LBmalt were significantly higher than those in MBmalt (Figs. 8). To increase the production of carotenoids in MBmalt, the cells should be kept in stationary phase for a longer time as seen in the single batch cultivation in MBmalt (Fig. 4b). Moreover, further study is needed to determine the concentration of total produced carotenoids to compare the total carotenoids production by R. marinus DSM 16675 and compare it with other thermophilic carotenoids producers.

In contrast to carotenoid production, there was poor EPSs production in LBmalt in each batch. The highest QE observed in cultivations in LBmalt was in batch 2 and 7, in which the cells remained in the stationary phase for a longer time period than in the other batches (Fig. 7a). The total concentration of produced EPSs was 3.77 (mg/L) with an overall QE of 0.1 (mg/L h) in the complete 7 batch cultivation sequence (of totally 35 h) of R. marinus DSM 16675 in LBmalt.

The EPSs production pattern in the batch sequence grown in MBmalt was different, as expected based on the single batch data (Fig. 3). In batch 1–3, QE increased significantly with growing cells, from 0.02 mg/L h in batch 1–1.42 mg/L h in batch 3. In the last two batches (3 and 4), the productivity was stable (Fig. 9). The total production of EPSs was 19 (mg/L) with an overall QE of 0.67 (mg/L h) during four batch sequences of R. marinus DSM 16675 in MBmalt. Interestingly, the EPSs concentration drastically decreased between batches, meaning that most of the EPSs is in solution and not tightly bound to the cells as tightly bound EPSs. The fact that most detected EPSs, produced by R. marinus DSM 16675, ar excreted into the medium has not previously been reported (Fig. 7B).

The total production of EPSs by R. marinus DSM 16675 was low in comparison to thermophiles with good production of EPSs, shown to reach EPS concentrations in the range of 55–897 mg/L (Kambourova et al. 2016). The reason might be due to harvesting the cells at the beginning of the stationary phase, since all good EPSs producers were reported to synthesize EPSs mainly during a prolonged stationary phase at low cell densities (Kambourova et al. 2016).

Conclusion

The present study describes different modes of operation for the cultivation of R. marinus DSM 16675 using two different complex media, LBmalt and MBmalt. Batch, fed-batch, and sequential batch cultivation techniques were used to evaluate the cell growth and product formation, focusing on carotenoids and EPSs. The results showed that LBmalt was a more suitable medium than MBmalt to obtain high cell densities, while MBmalt was a better option for the production of EPSs. However, the overall EPSs productivity of R. marinus DSM 16675 was low (3- to 40-fold) in comparison to other thermophilic bacteria (Kambourova et al. 2016) and needs further improvement. The monosaccharide composition of the EPSs differed, as the EPSs produced in MBmalt also contained xylose, while this was not the case for the EPSs produced in cultures grown in LBmalt. Carotenoids were produced by cultures grown in both media. The total carotenoids production in LBmalt was dependent on cell growth, while in MBmalt, the total carotenoids production was observed in both exponential phase and stationary phase.

The key difference between the batch and fed-batch cultivations contra cell recycling (also termed sequential batch) is that the medium is exchanged between cycles, which will have removed any accumulating inhibitory substances in the medium. The presence of such substances could explain why batch and fed-batch cultivations reach stationary phase at the same cell density, even though fed-batch theoretically should reach far higher cell densities. Growth limitation due to accumulation of metabolites has previously been reported for marine microorganisms (De Carvalho and Fernandes 2010). Further work needs to be performed to identify potential metabolites causing growth limitation of R. marinus DSM 16675.

References

Alfredsson G, Kristjansson J, Hjörleifsdottir S, Stetter K (1988) Rhodothermus marinus, gen. nov., sp. nov., a thermophilic, halophilic bacterium from submarine hot springs in Iceland. J Gen Microbiol 134:299–306

Bayles KW (2007) The biological role of death and lysis in biofilm development. Nat Rev Microbiol 5:721

Biehler E, Mayer F, Hoffmann L, Krause E, Bohn T (2010) Comparison of 3 spectrophotometric methods for carotenoid determination in frequently consumed fruits and vegetables. J Food Sci 75:C55–C61

Bjornsdottir SH, Fridjonsson OH, Hreggvidsson GO, Eggertsson G (2011) Generation of targeted deletions in the genome of Rhodothermus marinus. Appl Environ Microbiol 77:5505–5512

Blücher A, Karlsson E, Holst O (2000) Substrate-dependent production and some properties of a thermostable, α-galactosidase from Rhodothermus marinus. Biotechnol Lett 22:663–669

Cordova LT, Long CP, Venkataramanan KP, Antoniewicz MR (2015) Complete genome sequence, metabolic model construction and phenotypic characterization of Geobacillus LC300, an extremely thermophilic, fast growing, xylose-utilizing bacterium. Metab Eng 32:74–81

Cordova LT, Cipolla RM, Swarup A, Long CP, Antoniewicz MR (2017) 13C metabolic flux analysis of three divergent extremely thermophilic bacteria: Geobacillus sp. LC300, Thermus thermophilus HB8, and Rhodothermus marinus DSM 4252. Metab Eng 44:182–190

Crennell SJ, Hreggvidsson GO, Karlsson EN (2002) The structure of Rhodothermus marinus Cel12A, a highly thermostable family 12 endoglucanase, at 1.8 Å resolution. J Mol Biol 320:883–897

Dahlberg L, Holst O, Kristjansson JK (1993) Thermostable xylanolytic enzymes from Rhodothermus marinus grown on xylan. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 40:63–68

Das S, Mangwani N (2015) Ocean acidification and marine microorganisms: responses and consequences. Oceanologia 57:349–361

De Carvalho CCCR, Fernandes P (2010) Production of metabolites as bacterial responses to the marine environment. Mar Drugs 8:705–727

Degryse E, Glansdorff N, Piérard A (1978) A comparative analysis of extreme thermophilic bacteria belonging to the genus Thermus. Arch Microbiol 117:189–196

Demirtas MU, Kolhatkar A, Kilbane JJ (2003) Effect of aeration and agitation on growth rate of Thermus thermophilus in batch mode. J Biosci Bioeng 95:113–117

Flemming H-C, Neu TR, Wozniak DJ (2007) The EPS matrix: the “house of biofilm cells”. J Bacteriol 189:7945–7947

Gomes J, Steiner W (1998) Production of a high activity of an extremely thermostable β-mannanase by the thermophilic eubacterium Rhodothermus marinus, grown on locust bean gum. Biotechnol Lett 20:729–733

Gomes J, Gomes I, Terler K, Gubala N, Ditzelmüller G, Steiner W (2000) Optimisation of culture medium and conditions for α-L-arabinofuranosidase production by the extreme thermophilic eubacterium Rhodothermus marinus. Enzyme Microb Technol 27:414–422

Gomes I, Gomes J, Steiner W (2003) Highly thermostable amylase and pullulanase of the extreme thermophilic eubacterium Rhodothermus marinus: production and partial characterization. Bioresour Technol 90:207–214

Gray V, Müller C, Watkins I, Lloyd D (2008) Peptones from diverse sources: pivotal determinants of bacterial growth dynamics. J Appl Microbiol 104:554–565

Henke NA, Peters-Wendisch P, Wendisch VF (2017) Carotenoid production by Corynebacterium: the workhorse of industrial amino acid production as host for production of a broad spectrum of C40 and C50 carotenoids. IntechOpen, London, Carotenoids

Hobel CF, Hreggvidsson GO, Marteinsson VT, Bahrani-Mougeot F, Einarsson JM, Kristjansson JK (2005) Cloning, expression, and characterization of a highly thermostable family 18 chitinase from Rhodothermus marinus. Extremophiles 9:53–64

Holst O, Manelius Å, Krahe M, Märkl H, Raven N, Sharp R (1997) Thermophiles and fermentation technology. Comp Biochem Physiol A Physiol 118:415–422

Ibrahim MHA, Steinbüchel A (2010) High-cell-density cyclic fed-batch fermentation of a poly(3-hydroxybutyrate)-accumulating thermophile, Chelatococcus sp. Strain MW10. Appl Environ Microb 76:7890–7895

Kaiser P, Surmann P, Vallentin G, Fuhrmann H (2007) A small-scale method for quantitation of carotenoids in bacteria and yeasts. J Microbiol Meth 70:142–149

Kambourova M, Radchenkova N, Tomova I, Bojadjieva I (2016) Thermophiles as a promising source of exopolysaccharides with interesting properties. Biotechnology of extremophiles, Springer, Switzerland

Karlsson EN, Abou-Hachem M, Holst O, Danson MJ, Hough DW (2002) Rhodothermus marinus: a thermophilic bacterium producing dimeric and hexameric citrate synthase isoenzymes. Extremophiles 6:51–56

Kaur A, Capalash N, Sharma P (2018) Quorum sensing in thermophiles: prevalence of autoinducer-2 system. BMC Microbiol 18:1–16

Krahe M, Antranikian G, Märkl H (1996) Fermentation of extremophilic microorganisms. FEMS Microbiol Rev 18:271–285

Lazazzera BA (2000) Quorum sensing and starvation: signals for entry into stationary phase. Curr Opin Microbiol 3:177–182

Montgomery K, Charlesworth JC, LeBard R, Visscher PT, Burns BP (2013) Quorum sensing in extreme environments. Life 3:131–148

Navarro Llorens JM, Tormo A, Martínez-García E (2010) Stationary phase in gram-negative bacteria. FEMS Microbiol Rev 34:476–495

Nordberg Karlsson E, Bartonek-Roxå E, Holst O (1997) Cloning and sequence of a thermostable multidomain xylanase from the bacterium Rhodothermus marinus. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. Gene Struct Expression 1353:118–124

Nwodo UU, Green E, Okoh AI (2012) Bacterial exopolysaccharides: functionality and prospects. Int J Mol Sci 13:14002–14015

Ron EYC, Plaza M, Kristjansdottir T, Sardari RRR, Bjornsdottir SH, Gudmundsson S, Hreggvidsson GO, Turner C, van Niel EWJ, Nordberg-Karlsson E (2018) Characterization of carotenoids in Rhodothermus marinus. Microbiologyopen 7:1–9

Sardari RRR, Kulcinskaja E, Ron EYC, Björnsdóttir S, Friðjónsson ÓH, Hreggviðsson GÓ, Karlsson EN (2017) Evaluation of the production of exopolysaccharides by two strains of the thermophilic bacterium Rhodothermus marinus. Carbohydr Polym 156:1–8

Sengupta D, Datta S, Biswas D (2018) Towards a better production of bacterial exopolysaccharides by controlling genetic as well as physico-chemical parameters. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 102:1587–1598

Sezonov G, Joseleau-Petit D, D'Ari R (2007) Escherichia coli Physiology in Luria-Bertani Broth. J Bacteriol 189:8746–8749

Sluiter A, Hames B, Ruiz R, Scarlata C, Sluiter J, Templeton D, Crocker D (2008) Determination of structural carbohydrates and lignin in biomass. Technical report NREL/TP-510-42618.

Spilliaert R, Hreggvidsson GO, Kristjansson JK, Eggertsson G, Palsdottir A (1994) Cloning and sequencing of a Rhodothermus marinus gene, bglA, coding for a thermostable β-glucanase and its expression in Escherichia coli. Eur J Biochem 224:923–930

Tao Z, Wang G, Xu X, Yuan Y, Wang X, Li Y (2011) Monitoring and rapid quantification of total carotenoids in Rhodotorula glutinis cells using laser tweezers Raman spectroscopy. FEMS Microbiol Lett 314:42–48

Acknowledgements

Open access funding provided by Lund University. Financial support from the Processum foundation, the Era-net MBT project Thermofactories, the BBI, H2020 project Macrocascade, and the Novo Nordisk Foundation is greatly appreciated.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Communicated by A. Oren.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Ron, E.Y.C., Sardari, R.R.R., Anthony, R. et al. Cultivation technology development of Rhodothermus marinus DSM 16675. Extremophiles 23, 735–745 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00792-019-01129-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00792-019-01129-0