Abstract

Objective

Data from a trial of first-line panitumumab plus FOLFIRI (folinic acid, infusional 5-fluorouracil and irinotecan) in metastatic colorectal cancer were retrospectively analysed to investigate the effects of primary tumour location and early tumour shrinkage on outcomes.

Methods

Patients with RAS wild-type metastatic colorectal cancer from a single-arm, open-label phase II study (NCT00508404) were included. Tumours located from the splenic flexure to rectum and in the caecum to transverse colon were defined as left- and right-sided, respectively. Baseline characteristics were summarised by primary tumour location and the effects of primary tumour location on outcomes—including objective response rate, resection rate, depth of response, duration of response and progression-free survival—were analysed. Progression-free survival and objective response rate were analysed by early tumour shrinkage status.

Results

Primary tumour location was determined in 52/69 (75%) patients with RAS wild-type metastatic colorectal cancer; 45 (87%) had left-sided disease. Median progression-free survival was longer in patients with left-sided tumours (11.2 vs. 7.2 months for right-sided disease) and more of these patients experienced early tumour shrinkage ≥ 30% (53% vs. 29%). Early tumour shrinkage ≥ 30% was associated with improved progression-free survival irrespective of tumour location. More patients with early tumour shrinkage ≥ 30% achieved a partial or complete response. Objective response rate, duration of response, depth of response and resection rates were similar in patients with left- and right-sided tumours.

Conclusions

This analysis has confirmed a prognostic effect of primary tumour location in patients with RAS wild-type metastatic colorectal cancer receiving first-line panitumumab plus FOLFIRI. Early tumour shrinkage was associated with improved progression-free survival irrespective of tumour location. In right-sided disease, early tumour shrinkage may identify a subgroup of patients who might respond to panitumumab.

ClinicalTrials.gov identifier

NCT00508404.

Similar content being viewed by others

The site of origin of the primary tumour (left vs. right) in metastatic colorectal cancer is linked to better or poorer outcomes and response to therapy, for example, improved survival outcomes have been demonstrated in patients with RAS wild-type metastatic colorectal cancer with left-sided tumours receiving first-line panitumumab in combination with FOLFOX (folinic acid, infusional 5-fluorouracil and oxaliplatin) |

The current analysis involving the combination of panitumumab plus FOLFIRI (folinic acid, infusional 5-fluorouracil and irinotecan) confirms the prognostic effects of primary tumour location in patients receiving this treatment combination, specifically median progression-free survival was longer in patients with left-sided tumours |

The degree to which therapy can shrink a tumour within 8 weeks of treatment initiation predicts survival outcomes. In this analysis, more patients with left- vs. right- sided disease experienced early tumour shrinkage ≥ 30% and progression-free survival was longer in these patients. However, early tumour shrinkage ≥ 30% was associated with improved progression-free survival in patients regardless of primary tumour location |

1 Introduction

Targeted therapies such as inhibitors of the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) are key treatment options for metastatic colorectal cancer (mCRC) [1, 2]. However, tumour gene mutations in RAS are associated with a lack of response to EGFR-targeted agents in mCRC. For example, in a single-arm, open-label phase II study that is the focus of the retrospective analyses presented in this paper (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT00508404), the combination of the anti-EGFR monoclonal antibody panitumumab and FOLFIRI (folinic acid, infusional 5-fluorouracil and irinotecan) was associated with better clinical efficacy in patients with KRAS wild-type (WT) than in those with KRAS-mutant mCRC in the first-line setting [3, 4].

Panitumumab, in combination with FOLFIRI or FOLFOX (folinic acid, infusional 5-fluorouracil and oxaliplatin), is approved by the European Medicines Agency for the first-line treatment of patients with RAS WT mCRC [5]. In 2016, the European Society for Medical Oncology updated their consensus guideline, recommending doublet chemotherapy plus an anti-EGFR antibody as the preferred treatment for patients with RAS WT, to achieve a treatment goal of cytoreduction (tumour shrinkage) and conversion to resectable disease [1]. In line with this recommendation, treatment with anti-EGFR agents in mCRC have been associated with early tumour shrinkage (ETS), an emerging indicator of treatment response [6,7,8]. Used increasingly in studies of mCRC, ETS along with another newer endpoint, depth of response (DpR), provide information on tumour shrinkage over and above that provided by the more traditional Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST) [9, 10]. Early tumour shrinkage offers an early indication of sensitivity to treatment, while DpR reveals the maximum tumour shrinkage achieved; both may relate to overall and post-progression survival [7, 11,12,13]. Early tumour responses also accompany relief from tumour-associated symptoms [14]. Interestingly, in a recent analysis of the FIRE-3 study, ETS identified subgroups of patients with both BRAF- and RAS-mutant mCRC who were sensitive to anti-EGFR therapy. Early tumour shrinkage was associated with significantly longer overall survival (OS) in these patients. No predictive value of ETS for OS was observed in patients with BRAF- or RAS-mutant mCRC receiving vascular endothelial growth factor A inhibition therapy [15].

Primary tumour location has been identified as a surrogate marker for tumour biology and has a prognostic impact in patients with mCRC. Specifically, patients with left-sided mCRC tumours have a more favourable prognosis than patients with right-sided tumours [16,17,18,19,20]. These two tumour types differ in aetiology, prevalence, molecular signature and microbiome [16, 19, 21]. Right-sided tumours are less prevalent but generally have a higher disease stage at presentation and more frequently harbour BRAF V600 mutations [16, 18, 19]. In contrast, chromosomal instability, gene amplification of HER2 and overexpression of EGFR ligands are more common in left- than right-sided tumours [19].

Recent retrospective analyses of randomised clinical studies suggest that survival outcomes are improved in patients with primary left-sided tumours receiving treatment with an EGFR-targeted agent vs. comparator regimens, both in first and later lines of treatment [22,23,24,25,26]. A pooled analysis of six randomised studies that investigated the prognostic and predictive value of primary tumour location for targeted agents in first- or second-line mCRC treatment confirmed a significant benefit for chemotherapy plus anti-EGFR therapy in patients with left-sided tumours in terms of OS and progression-free survival (PFS), compared with no significant benefit for those with right-sided tumours [25]. However, numerical increases in overall response rate were observed in both patients with right- and left-sided tumours who received anti-EGFR treatment [25]. Despite the limitations of retrospective analyses, the data strongly suggest a greater benefit from treatment with chemotherapy plus anti-EGFR agents for patients with left- vs. right-sided RAS WT tumours. However, the data also highlight that some patients with right-sided disease may benefit from anti-EGFR treatment where cytoreduction is the goal [25]. The impact of tumour location has been investigated in retrospective analyses of trials of first-line panitumumab in combination with FOLFOX, and of the anti-EGFR antibody cetuximab plus FOLFIRI [22, 25]. To confirm that the effects are consistent for the combination of panitumumab plus FOLFIRI, we report here additional exploratory analyses of the first-line trial of panitumumab plus FOLFIRI (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT00508404). These analyses aim to investigate the effects of primary tumour location on efficacy outcomes, including ETS, in patients with RAS WT mCRC. The association between ETS and treatment efficacy with regard to PFS and objective response rate (ORR) will also be explored. Preliminary results from this analysis have been presented in abstract form [27].

2 Methods

2.1 Study Design

This is a retrospective analysis of the single-arm, open-label phase II study of first-line panitumumab plus FOLFIRI in patients with mCRC (NCT00508404). Details of this study have been published previously [3, 4]. In short, first-line panitumumab 6 mg/kg plus FOLFIRI was administered once every 2 weeks until disease progression (PD). The primary study endpoint was ORR, assessed per modified RECIST version 1 [28]. Other efficacy endpoints included duration of response and PFS. The incidence of resection of metastases was also reported. Only study patients with RAS WT mCRC (i.e., with tumours containing no mutations in KRAS or NRAS exons 2 [codons 12/13], 3 [codons 59/61] and 4 [codons 117/146]) were included in the current analyses.

2.2 Analyses According to Primary Tumour Location

Primary tumour location was determined from free-text surgery descriptions included in case report forms and/or original pathology reports. Primary tumours located in the caecum to transverse colon were defined as right-sided; tumours located from the splenic flexure to rectum were categorised as left-sided. Patient demographics and disease characteristics at baseline were summarised by primary tumour location.

Radiographic images by computer tomography or magnetic resonance imaging were obtained at screening and every 8 weeks ± 1 week until disease progression and the effect of primary tumour location on the following outcomes was analysed: ETS, objective response, DpR, duration of response and resection rate. Early tumour shrinkage was defined as a ≥ 30% reduction in the sum of the longest diameters of measurable target lesions at week 8. Depth of response was the maximum percentage change from baseline to nadir in patients who had shrinkage, or the percentage change at PD in patients with no shrinkage. Depth of response has a zero value for no change, a positive value for tumour reduction and a negative value for tumour growth. Duration of response was calculated from first confirmed response to first occurrence of PD, per modified RECIST version 1. Progression-free survival was calculated from the enrolment date to the date of first observed PD or death as a result of any cause (whichever occurred first). In addition to analyses by primary tumour location, PFS and ORR were also analysed by ETS status. There was no long-term follow-up of OS in this study.

2.3 Statistical Analysis

No formal hypothesis testing was planned for this retrospective analysis. All data were summarised descriptively. For continuous endpoints, the median and interquartile range were provided. For discrete data, frequency and percent distributions were presented. Kaplan–Meier estimates and associated 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated for median PFS. Hazard ratios (HRs) and associated 95% CIs were estimated from a Cox proportional hazard model. No adjustments to this model were made.

3 Results

3.1 Patients

As previously reported, 154 patients were enrolled in the study and complete RAS data were available for 143 patients [3, 4]. Of these, 69 patients had RAS WT mCRC, nine of whom had BRAF mutations [3, 4]. Among the 52 (75%) patients with RAS WT for whom the primary tumour location could be determined, 45 (87%) had left-sided tumours and 7 (13%) had right-sided tumours. Tumour location could not be determined in 17 patients as insufficient information was available in either the case report form or the pathology report. Compared with patients with right-sided tumours, more patients with left-sided tumours had BRAF WT mCRC, an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status of 0, liver plus other metastases, and had received prior adjuvant chemotherapy (Table 1).

3.2 Impact of Primary Tumour Location on Study Drug Exposure and Efficacy Outcomes

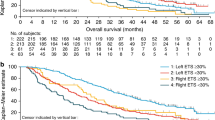

More patients with left- vs. right-sided tumours received the study drug for at least 6 months (56% vs. 43%; Table 2). Patients with left-sided tumours also more frequently experienced ETS ≥ 30% compared with those with right-sided tumours (53% vs. 29%; Table 3). Median PFS was 11.2 months and 7.2 months for patients with left- and right-sided tumours, respectively (HR 1.45 [95% CI 0.56–3.77]; Fig. 1). Objective response rate (60% vs. 57%), median duration of response (13.2 [95% CI 9.3–47.7] vs. 14.3 [3.5–17.3] months), median DpR (61% vs. 60%) and resection rates (any resection: 13% vs. 14%) were similar for patients with left- and right-sided disease (Table 3).

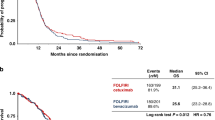

Early tumour shrinkage ≥ 30% was associated with improved PFS irrespective of primary tumour location (left-sided HR 0.53 [95% CI 0.22–1.29]; right-sided HR 0.35 [0.03–3.54]; Table 3 and Fig. 2). More patients with ETS ≥ 30% experienced a partial response or complete response to treatment compared with patients with ETS < 30% (Table 3 and Fig. 3). Of those patients with ETS < 30%, 33% (11/30) of patients later achieved a complete or partial response.

Impact of early tumour shrinkage (ETS) on objective response rate: waterfall plot of relative changes in maximum tumour diameter after 8 weeks of treatment, ETS and characterisation of best objective response (n = 65). Response evaluation according to modified Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors version 1 (mRECIST v.1). CR complete response, PD progressive disease, PR partial response, SD stable disease

4 Discussion

We performed a post-hoc exploratory analysis of a single-arm, open-label phase II study of panitumumab plus FOLFIRI as first-line treatment of mCRC to investigate the effects of primary tumour location on additional endpoints. We observed ETS in both left- and right-sided mCRC tumours after treatment with panitumumab plus FOLFIRI, although more patients with left-sided disease experienced ETS. This finding is in line with data from a recent retrospective analysis of data from patients with RAS WT who participated in either a phase III study (PRIME) that compared panitumumab plus FOLFOX4 vs. FOLFOX4 alone or a phase II study (PEAK) that compared mFOLFOX6 plus panitumumab or bevacizumab [8].

Irrespective of tumour location, ETS ≥ 30% was associated with longer PFS in this study (compared with ETS < 30%). In line with this finding, a higher proportion of patients with left- vs. right-sided disease achieved ETS ≥ 30% and PFS was longer (11.2 vs. 7.2 months) in these patients. These data are aligned with larger analyses suggesting improved survival outcomes are associated with achievement of ETS in patients with RAS WT mCRC receiving panitumumab treatment [7]. In the PRIME study, treatment with first-line panitumumab plus FOLFOX4 compared with FOLFOX4 alone resulted in a significantly higher percentage of patients achieving ETS ≥ 30% at week 8 (59% vs. 38%, p < 0.001) [7]. Moreover, regardless of treatment arm, ETS was associated with improved PFS and OS [7]. Relevant data have also been published from the PLANET-TTD study of previously untreated patients with KRAS WT mCRC randomised to panitumumab plus FOLFOX4 or panitumumab plus FOLFIRI [29]. In that study, 68% of patients with RAS WT mCRC receiving first-line panitumumab plus FOLFIRI (n = 26) had ETS [29]. Although focused on the peri-operative period in mCRC, median PFS in these patients was numerically higher than in patients with ETS < 30% (HR ETS ≥ 30% vs. < 30% [95% CI]: 0.6 [0.2–1.5], p = 0.253). Considering all patients receiving panitumumab plus either FOLFOX or FOLFIRI (n = 53), median PFS was significantly longer in patients with ETS ≥ 30% (15 months) than in those with ETS < 30% (8 months; HR [95% CI] 0.5 [0.2–0.9], p = 0.013) [29].

We also report here that more patients with ETS ≥ 30% experienced a partial or complete response to treatment compared with patients with ETS < 30%. However, it is important to note that one third of patients who did not achieve ETS ≥ 30% went on to achieve a partial or complete response. A notable aspect of ETS is the associated symptomatic benefit for patients. In a recent analysis of PRIME, patients with tumour-related symptoms at baseline who achieved ETS ≥ 30% had statistically significant improvements in quality of life prior to discontinuation of first-line treatment compared with patients without ETS [14]. Forthcoming studies, designed to prospectively measure ETS, will be important to establish the use of this endpoint in mCRC trials.

In the current study, median PFS was significantly longer in patients with left- vs. right-sided tumours. This finding is in line with those from the CRYSTAL, FIRE-3 and CALGB/SWOG 80405 trials in which patients with RAS WT mCRC were treated with first-line cetuximab plus FOLFIRI or FOLFIRI [20, 23], and is also in agreement with a recent retrospective analysis of the PRIME and PEAK studies [22]. However, in the current study, ORR appeared to be similar regardless of primary tumour location, which differs from recently published data that indicate a higher ORR for left-sided tumours [22, 23]. In the original analysis of the current study [3], ORR in patients with KRAS WT was similar to that reported in the CRYSTAL study (56% and 59%, respectively) [30]. In the current analysis, DpR was also similar in left- and right-sided disease; whereas in the PRIME and PEAK studies, DpR was higher in left- vs. right-sided disease overall and with panitumumab treatment [8]. The discrepancy between these analyses of ORR and DpR could be related to the limited number of right-sided tumours identified in the current analysis.

This study provides further insights into the impact of primary tumour location on outcomes using analysis of additional response measures. However, interpretation of this analysis is restricted by the single-arm design of the study and the limited sample size. The sample size was further reduced by the fact that insufficient information was available in either the case report form or the pathology report to provide primary tumour location data for 25% of patients with RAS WT mCRC, which may have impacted on the validity of these analyses. Of note, the subgroup of patients with right-sided disease contained a very small number of patients, preventing definitive conclusions in these patients to be drawn. Furthermore, in line with previous reports [31], more patients with right-sided disease had BRAF-mutated mCRC (29% vs. 9% in patients with left-sided disease). As BRAF mutations are associated with poor prognosis in mCRC [31], this difference may have contributed to the difference in PFS observed between the two groups. However, previous analyses have found that prognosis remains poor in patients with RAS/BRAF WT right-sided disease compared with those with RAS/BRAF WT left-sided mCRC [22].

Despite these limitations, our post-hoc study is the first to report data on tumour location in a trial of first-line panitumumab with FOLFIRI, and the findings align with those reported by larger randomised studies, including those of doublet chemotherapies with anti-EGFR monoclonal antibodies, regarding the association between PFS and ETS. The data also support the conclusions from similar analyses with panitumumab in later lines [26]. It is of interest that in the current study, two out of seven patients with right-sided tumours showed more than a 30% tumour reduction. This suggests that anti-EGFR therapy could be a treatment option in some patients with right-sided tumours. For example, those requiring rapid symptom relief or treatment with the goal of achieving tumour shrinkage to enable secondary resection. This is supported by a retrospective analysis from the European Society for Medical Oncology which, based on data indicating improved ORR with EGFR-targeted treatment in patients with right-sided RAS WT tumours, states that doublet chemotherapy plus EGFR antibody remains a therapy option for these patients where cytoreduction is the treatment goal [25].

5 Conclusions

The current analyses of first-line panitumumab plus FOLFIRI in patients with mCRC have confirmed a prognostic effect of primary tumour location. The results presented here are in line with those from larger studies suggesting improved ETS and PFS with anti-EGFR treatment plus doublet chemotherapy in RAS WT left-sided mCRC. Irrespective of tumour location, ETS was associated with improved PFS. Although no firm conclusions can be drawn regarding the activity of panitumumab plus FOLFIRI in patients with RAS WT right-sided mCRC owing to the small patient numbers, the presence of ETS in these patients may also predict a PFS benefit from continued treatment in this subpopulation. Panitumumab plus FOLFIRI is an effective first-line treatment for patients with left-sided RAS WT mCRC and remains an option for a subgroup of patients with right-sided tumours.

References

Van Cutsem E, Cervantes A, Adam R, Sobrero A, Van Krieken JH, Aderka D, et al. ESMO consensus guidelines for the management of patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. Ann Oncol. 2016;27:1386–422.

National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Clinical practice guidelines in oncology: colon cancer. Version 2. 2019. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/colon_blocks.pdf. Accessed 13 June 2019.

Kohne CH, Hofheinz R, Mineur L, Letocha H, Greil R, Thaler J, et al. First-line panitumumab plus irinotecan/5-fluorouracil/leucovorin treatment in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2012;138:65–72.

Karthaus M, Hofheinz R-D, Mineur L, Letocha H, Greil R, Thaler J, et al. Impact of tumour RAS/BRAF status in a first-line study of panitumumab + FOLFIRI in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. Br J Cancer. 2016;115:1215–22.

European Medicines Agency. Vectibix® (panitumumab): summary of product characteristics. 2018. http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/EPAR_-_Product_Information/human/000741/WC500047710.pdf. Accessed 13 June 2019.

Hu J, Zhang Z, Zheng R, Cheng L, Yang M, Li L, et al. On-treatment markers as predictors to guide anti-EGFR MoAb treatment in metastatic colorectal cancer: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2017;79:275–85.

Douillard JY, Siena S, Peeters M, Koukakis R, Terwey JH, Tabernero J. Impact of early tumour shrinkage and resection on outcomes in patients with wild-type RAS metastatic colorectal cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2015;51:1231–42.

Peeters M, Price T, Taieb J, Geissler M, Rivera F, Canon J-L, et al. Relationships between tumour response and primary tumour location, and predictors of long-term survival, in patients with RAS wild-type metastatic colorectal cancer receiving first-line panitumumab therapy: retrospective analyses of the PRIME and PEAK clinical trials. Br J Cancer. 2018;119:303–12.

Taieb J, Rivera F, Siena S, Karthaus M, Valladares-Ayerbes M, Gallego J, et al. Exploratory analyses assessing the impact of early tumour shrinkage and depth of response on survival outcomes in patients with RAS wild-type metastatic colorectal cancer receiving treatment in 3 randomised panitumumab trials. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2017;144:321–35.

Eisenhauer EA, Therasse P, Bogaerts J, Schwartz LH, Sargent D, Ford R, et al. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1). Eur J Cancer. 2009;45:228–47.

Heinemann V, Stintzing S, Modest DP, Giessen-Jung C, Michl M, Mansmann UR. Early tumour shrinkage (ETS) and depth of response (DpR) in the treatment of patients with metastatic colorectal cancer (mCRC). Eur J Cancer. 2015;51:1927–36.

Stintzing S, Modest DP, Rossius L, Lerch MM, von Weikersthal LF, Decker T, et al. FOLFIRI plus cetuximab versus FOLFIRI plus bevacizumab for metastatic colorectal cancer (FIRE-3): a post-hoc analysis of tumour dynamics in the final RAS wild-type subgroup of this randomised open-label phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17:1426–34.

Piessevaux H, Buyse M, Schlichting M, Van Cutsem E, Bokemeyer C, Heeger S, Tejpar S. Use of early tumor shrinkage to predict long-term outcome in metastatic colorectal cancer treated with cetuximab. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:3764–75.

Siena S, Tabernero J, Bodoky G, Cunningham D, Rivera F, Ruff P, et al. Quality of life during first-line FOLFOX4 ± panitumumab in RAS wild-type metastatic colorectal carcinoma: results from a randomised controlled trial. ESMO Open. 2016;1:e000041.

Stintzing S, Miller-Phillips L, Modest DP, Fischer von Weikersthal L, Decker T, Kiani A, et al. Impact of BRAF and RAS mutations on first-line efficacy of FOLFIRI plus cetuximab versus FOLFIRI plus bevacizumab: analysis of the FIRE-3 (AIO KRK-0306) study. Eur J Cancer. 2017;79:50–60.

Holch JW, Ricard I, Stintzing S, Modest DP, Heinemann V. The relevance of primary tumour location in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer: a meta-analysis of first-line clinical trials. Eur J Cancer. 2017;70:87–98.

Petrelli F, Tomasello G, Borgonovo K, Ghidini M, Turati L, Dallera P, et al. Prognostic survival associated with left-sided vs right-sided colon cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3:211–9.

Loupakis F, Yang D, Yau L, Feng S, Cremolini C, Zhang W, et al. Primary tumor location as a prognostic factor in metastatic colorectal cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2015;107:dju427.

Stintzing S, Tejpar S, Gibbs P, Thiebach L, Lenz HJ. Understanding the role of primary tumour localisation in colorectal cancer treatment and outcomes. Eur J Cancer. 2017;84:69–80.

Venook AP, Niedzwiecki D, Innocenti F, Fruth B, Greene C, O’Neil BH, et al. Impact of primary tumor location on overall survival (OS) and progression-free survival (PFS) in patients (pts) with metastatic colorectal cancer (mCRC): analysis of CALGB/SWOG 80405 (Alliance). J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:3504.

Lee GH, Malietzis G, Askari A, Bernardo D, Al-Hassi HO, Clark SK. Is right-sided colon cancer different to left-sided colorectal cancer? A systematic review. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2015;41:300–8.

Boeckx N, Koukakis R, de Beeck OK, Rolfo C, Van Camp G, Siena S, et al. Primary tumor sidedness has an impact on prognosis and treatment outcome in metastatic colorectal cancer: results from two randomized first-line panitumumab studies. Ann Oncol. 2017;28:1862–8.

Tejpar S, Stintzing S, Ciardiello F, Taberno J, Van Cutsem E, Beier F, et al. Prognostic and predictive relevance of primary tumor location in patients with RAS wild-type metastatic colorectal cancer: retrospective analyses of the crystal and fire-3 trials. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3:194–201.

Moretto R, Cremolini C, Rossini D, Pietrantonio F, Battaglin F, Mennitto A, et al. Location of primary tumor and benefit from anti-epidermal growth factor receptor monoclonal antibodies in patients with RAS and BRAF wild-type metastatic colorectal cancer. Oncologist. 2016;21:988–94.

Arnold D, Lueza B, Douillard JY, Peeters M, Lenz HJ, Venook A, et al. Prognostic and predictive value of primary tumour side in patients with RAS wild-type metastatic colorectal cancer treated with chemotherapy and EGFR directed antibodies in six randomized trials. Ann Oncol. 2017;28:1713–29.

Boeckx N, Koukakis R, Op de Beeck K, Rolfo C, Van Camp G, Siena S, et al. Effect of primary tumor location on second- or later-line treatment outcomes in patients with RAS wild-type metastatic colorectal cancer and all treatment lines in patients with RAS mutations in four randomized panitumumab studies. Clin Colorectal Cancer. 2018;17:170–8.

Karthaus M, Eynde MVD, Mineur L, Thaler J, Koukakis R, Berkhout M, Gallego J. Impact of primary tumour location (PTL) on outcomes in patients (pts) with metastatic colorectal cancer (mCRC) undergoing first-line panitumumab (Pmab) + FOLFIRI treatment. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36:820.

Therasse P, Arbuck SG, Eisenhauer EA, Wanders J, Kaplan RS, Rubinstein L, et al. New guidelines to evaluate the response to treatment in solid tumors. European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer, National Cancer Institute of the United States, National Cancer Institute of Canada. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92:205–16.

Carrato A, Abad A, Massuti B, Gravalos C, Escudero P, Longo-Munoz F, Spanish Cooperative Group for the Treatment of Digestive Tumours (TTD), et al. First-line panitumumab plus FOLFOX4 or FOLFIRI in colorectal cancer with multiple or unresectable liver metastases: a randomised, phase II trial (PLANET-TTD). Eur J Cancer. 2017;81:191–202.

Van Cutsem E, Kohne CH, Hitre E, Zaluski J, Chang Chien CR, Makhson A, et al. Cetuximab and chemotherapy as initial treatment for metastatic colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:1408–17.

Tran B, Kopetz S, Tie J, Gibbs P, Jiang ZQ, Lieu CH, et al. Impact of BRAF mutation and microsatellite instability on the pattern of metastatic spread and prognosis in metastatic colorectal cancer. Cancer. 2011;117:4623–32.

Acknowledgements

We thank all of the patients, their families and the investigators involved in the original study (NCT00508404). Medical writing support (including editing and expansion of an author (MB)-written first draft, development of subsequent drafts in consultation with the authors, assembling tables and figures, collating author comments, copyediting, fact checking and referencing) was provided by Louise Niven DPhil, CMPP at Aspire Scientific Limited (Bollington, UK) and was funded by Amgen (Europe) GmbH (Rotkreuz, Switzerland).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

The original study (NCT00508404) and performance of the retrospective analyses described here were supported by Amgen Inc, and medical writing assistance was funded by Amgen (Europe) GmbH.

Conflict of Interest

Claus-Henning Köhne has received honoraria from Amgen, Bayer, Merck, Pfizer and Servier. Meinolf Karthaus has consulting/advisory roles and has participated in steering committees for Amgen and has received travel/accommodation/expenses from Amgen. Laurent Mineur has consulting/advisory roles for Bayer and Merck, and has received travel/accommodation/expenses from Merck and Ipsen, honoraria from Amgen, Bayer, Ipsen, Merck and Sanofi, and research funding from Chugai, Merck and Sanofi. Josef Thaler has received honoraria and research funding from Amgen. Marc Van den Eynde has consulting/advisory roles for Amgen, Bayer, Merck and Servier, and has received travel/accommodation/expenses from Amgen, Bayer, Merck and Roche, honoraria from Amgen, Bayer, Merck, Roche, Sanofi and Servier, and research funding from Roche. Javier Gallego has consulting/advisory roles for Amgen, Bayer, Celgene, Lilly, Merck Serono, Roche and Sanofi. Reija Koukakis is an Amgen Ltd. employee and owns restricted shares in Amgen. Marloes Berkhout is an Amgen (Europe) GmbH employee and owns restricted shares in Amgen. Ralf-Dieter Hofheinz has received honoraria (lecturer fees) and clinical trial funding from Amgen Ltd. and Merck.

Ethics Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institution and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Consent to Participate

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study. No additional consent was required for these retrospective analyses.

Author Contributions

RK and MB were involved in the conception and design of the analyses. RK performed the statistical analyses. C-HK, MK, LM, JT and R-DH collected study data. All authors contributed to the interpretation of the data, the preparation and revision of the manuscript, and approved the final version.

Data Availability

There is a plan to share data. This may include de-identified individual patient data for variables necessary to address the specific research question in an approved data-sharing request; also related data dictionaries, study protocol, statistical analysis plan, informed consent form and/or clinical study report. Data sharing requests relating to data in this manuscript will be considered after the publication date and (1) this product and indication (or other new use) have been granted marketing authorisation in both the USA and Europe or (2) clinical development discontinues and the data will not be submitted to regulatory authorities. There is no end date for eligibility to submit a data sharing request for these data. Qualified researchers may submit a request containing the research objectives, the Amgen product(s) and Amgen study/studies in scope, endpoints/outcomes of interest, statistical analysis plan, data requirements, publication plan and qualifications of the researcher(s). In general, Amgen does not grant external requests for individual patient data for the purpose of re-evaluating safety and efficacy issues already addressed in the product labelling. A committee of internal advisors reviews requests. If not approved, a Data Sharing Independent Review Panel will arbitrate and make the final decision. Upon approval, information necessary to address the research question will be provided under the terms of a data sharing agreement. This may include anonymised individual patient data and/or available supporting documents, containing fragments of analysis code where provided in analysis specifications. Further details are available at http://www.amgen.com/datasharing.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Köhne, CH., Karthaus, M., Mineur, L. et al. Impact of Primary Tumour Location and Early Tumour Shrinkage on Outcomes in Patients with RAS Wild-Type Metastatic Colorectal Cancer Following First-Line FOLFIRI Plus Panitumumab. Drugs R D 19, 267–275 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40268-019-0278-8

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40268-019-0278-8