Abstract

Sequential treatment of a previously-calcined solid oxide support (i.e. SiO2, γ-Al2O3, or mixed SiO2–Al2O3) with solutions of Cr{N(SiMe3)2}3 (0.71 wt% Cr) and a Lewis acidic alkyl aluminium-based co-catalyst (15 molar equivalents) affords initiator systems active for the oligomerisation and/or polymerisation of ethylene. The influence of the oxide support, calcination temperature, co-catalyst, and reaction diluent on both the productivity and selectivity of the immobilised chromium initiator systems have been investigated, with the best performing combination (SiO2−600, modified methyl aluminoxane-12 {MMAO-12}, heptane) producing a mixture of hexenes (61 wt%; 79% 1-hexene), and polyethylene (16 wt%) with an activity of 2403 g gCr−1 h−1. The observed product distribution is rationalised by two competing processes: trimerisation via a supported metallacycle-based mechanism and polymerisation through a classical Cossee-Arlman chain-growth pathway. This is supported by the indirect observation of two distinct chromium environments at the surface of the oxide support by a solid-state 29Si NMR spectroscopic study of the Cr{N(SiMe3)2}x/SiO2−600 pro-initiator.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Today’s market for short-chain linear α-olefins (LAOs) is so demanding that the traditional synthetic routes for their manufacture such as Ziegler- and SHOP-type oligomerisation processes, which give rise to statistical LAO product distributions, cannot keep pace [1]. As 1-hexene is an important commodity chemical that is used extensively on a large scale in the manufacture of linear low density and high density polyethylene (LLDPE and HDPE, respectively), it is becoming imperative that new routes that optimise selectivity for 1-hexene over less useful LAO product fractions are found [2]. Therefore, selective ethylene trimerisation has become the focus of much research in both academia and industry [3]. For example, Union Carbide [4,5,6], Chevron-Phillips [7,8,9] and BP [10, 11] have each developed their own homogeneous chromium-based catalyst packages for upgrading ethylene to 1-hexene. Each of these systems typically comprise a soluble chromium source, a ligand (often a tight bite angle diphosphine), and an alkyl aluminium activator such as methyl aluminoxane (MAO).

Conversely, there are relatively few examples of selective heterogeneous ethylene oligomerisation initiators having been reported [12,13,14,15,16,17,18]. Such heterogeneous systems could provide several advantages over their soluble counterparts in an industrial context, which include more efficient separation of the liquid product stream from the solid catalyst, the potential for a “solvent-free” continuous flow process, and minimisation of reactor fouling [19]. However, one barrier to the development of such heterogeneous systems is their complexity. Even for established homogeneous chromium-based selective olefin oligomerisation systems, where aspects of the general catalytic mechanism have been elucidated [1, 20], most notably the role of a metallacyclic reaction pathway (Scheme 1) [1, 21], there remains considerable debate about their precise mode of operation, including the formal oxidation states of the catalytically-active chromium species and specific aspects of ligand control [22,23,24,25]. Indeed, it is well-documented that catalytic performance relies on a complex interplay of factors including not only the structure of the molecular precursor and its supporting ligands, but also the nature of the aluminium activator, reaction solvent, and process conditions [26].

The origin of the selectivity towards ethylene trimerisation achievable with the established homogeneous systems is widely believed to result from operation of a metallacycle-based mechanism, as initially proposed by Manyik and later modified by Briggs (Scheme 1) [4, 6]. Here, chromium is thought to facilitate the oxidative coupling of ethylene, resulting in the formation of a five-membered chromacyclopentane [4]. Subsequent ethylene coordination and migratory insertion leads to the formation of a seven-membered metallacycle, which undergoes sequential β-hydride and reductive elimination steps to produce the target 1-hexene [6]. The selectivity of the process is thus controlled by the relative stabilities of the five- versus the seven-membered metallacycles, and by the rate of elimination of 1-hexene from the metallacycloheptane being faster than further insertion of ethylene to yield larger metallacycles [6].

This paper reports our findings from a fundamental study of the factors that influence the performance of a heterogeneous olefin trimerisation catalyst through use of a modification of a previously reported oxide-supported chromium initiator system developed by Monoi and Sasaki [18]. In particular, an assessment is made here of the relationship between the nature of the oxide support and its pre-treatment, the nature of the alkyl aluminium-based activator, and the reaction diluent against the performance of the heterogeneous ethylene trimerisation catalyst.

2 Results and Discussion

The catalyst described by Monoi and Sasaki comprises an oxide-supported chromium pro-initiator, prepared through reaction of a well-defined molecular chromium(III) tris-(amide) complex with a partially dehydroxylated silica support, which is then activated using an alkyl aluminium reagent [18]. This system provides a convenient starting point here for developing future understanding.

2.1 Preparation and Optimisation of Cr{N(SiMe3)2}x/Oxide−600 Ethylene Oligomerisation Initiators

2.1.1 Effect of Oxide Support

Partially-dehydroxylated SiO2 (Evonik Aeroperl 300/30), mixed SiO2–Al2O3 (Sigma Aldrich SiO2–Al2O3 Grade 135 catalyst support), and γ-Al2O3 (Alfa Aesar γ-Al2O3) were screened as potential catalyst supports in chromium-mediated ethylene oligomerisation. To enable comparison with the prior work of Monoi [18], each of the oxide materials was initially calcined at 600 °C for 24 h under a flow of dry nitrogen (the resulting materials being denoted as oxide−600). Subsequently, without exposure to the atmosphere, each of the oxide−600 materials was treated with a heptane solution of Cr{N(SiMe3)2}3 at room temperature (10 h) to afford materials with 0.71 wt% Cr loadings. The ethylene oligomerisation performance of the three oxide−600-bound chromium systems was then assessed in the slurry phase using modified methyl aluminoxane-12, MMAO-12, (Al:Cr = 15:1; toluene solution) as activator under identical test conditions, namely 8 barg ethylene, 120 °C, heptane solvent. For comparison, a homogeneous solution of Cr{N(SiMe3)2}3 was activated with MMAO-12 and tested in an analogous fashion.

The preliminary test results (Table 1) show that both the SiO2−600- and SiO2–Al2O3−600-supported systems afford hexenes as the principle products, with moderate selectivity to 1-hexene in both cases (Entries 2, 3), broadly in agreement with the previous observations of Monoi using a related silica-supported initiator [18]. In contrast, the γ-Al2O3−600-based system shows a complete switch in product selectivity not only favouring the formation of polyethylene (PE) rather than oligomerisation, but also showing significantly lower catalytic activity (Entry 4). Both the SiO2- and SiO2–Al2O3-supported systems demonstrate selectivity to C6 and C10 products rather than statistical product distributions. Catalytic tests undertaken using the soluble Cr{N(SiMe3)2}3 complex in combination with MMAO-12 as activator (Entry 1) give rise to extremely low productivity as well as a preference towards polymer formation. Together these observations are consistent with the oxide support playing an intimate role in the stabilisation of the active chromium species, as well as determining the nature of the catalytically-active chromium functionalities.

2.1.2 Effect of Aluminium Activator

It is well established that the nature of the Lewis acidic aluminium activator has a profound impact on the performance of early transition metal olefin oligomerisation systems, both in terms of activity as well as product selectivity [26, 27]. Although the identity of the active species responsible for selective homogeneously-catalysed ethylene trimerisation remains elusive, Bercaw et al. have provided compelling evidence that suggests that the Lewis acidic co-catalyst abstracts a ligand to produce a cationic CrIII species, which then undergoes reductive elimination to form the active CrI trimerisation catalyst [28]. Consequently, it was important to explore whether such activator dependence was also observed for oxide-supported chromium amide-derived systems. To this end, a series of Lewis acidic co-catalysts, iBu3Al, isobutyl aluminoxane (IBAO), Me3Al, methyl aluminoxane (MAO), modified methyl aluminoxane-12 (MMAO-12) and Et2AlCl, were screened in combination with the Cr{N(SiMe3)2}x/SiO2−600 pro-initiator (Table 2).

In line with the established trends demonstrated by homogeneous chromium-mediated ethylene oligomerisation initiators, the performance of the Cr{N(SiMe3)2}x/SiO2−600 system also exhibits a dependency on the nature of the Lewis acidic co-catalyst. Under the reaction conditions employed, MMAO-12 proved to be the optimal activator, both in terms of activity and selectivity towards 1-hexene (Table 2, Entry 2). Notably, in our hands, activation using IBAO afforded a system that was an order of magnitude less active and produced comparatively high levels of heavier oligomers (C12+) compared to the results described by Monoi [18]. While the origins of the enhanced performance of MMAO-12 in this initiator system remain obscure, it is likely that the greater thermal stability and better solubility of MMAO-12 in heptane compared with that of the other aluminium reagents, including MAO (Table 2, Entry 6), is a significant factor under the catalyst test conditions employed herein (i.e. heptane diluent, 120 °C) [29, 30]. However, the precise roles and modes of action of alkyl aluminium-based activators in both olefin oligomerisation and polymerisation are complex and generally remain rather poorly understood [30]. Consequently, it is possible that other factors may also contribute to differences observed between the performance of the various co-catalysts screened herein. These include potential coordination of alkyl aluminium species to the active chromium centre either directly or through ligation of the pendant amide groups, processes that can impede olefin coordination and provide a pathway for alkyl chain transfer [31,32,33,34]. Furthermore, since calcined oxides such as silica and alumina are established supports for alkyl aluminium activators (e.g. MAO and MMAO) themselves in both olefin oligomerisation and polymerisation catalysis, binding of the aluminium-based co-catalysts to the SiO2−600 cannot be ruled out, something that may also lead to a modification of the aluminoxanes through sequestration of residual trialkyl aluminium species [35, 36]. Studies to further probe the specific activator dependence observed here are on-going.

2.1.3 Effect of Diluent

Previous studies have shown that homogeneous ethylene oligomerisation processes are subject to substantial solvent effects [29, 37]. Accordingly, a series of batch ethylene oligomerisation runs using the heterogeneous Cr{N(SiMe3)2}x/SiO2−600 system were conducted to explore the impact of the organic diluent phase on catalytic performance (Table 3). The results indicate that the oxide-supported initiators perform best in aliphatic, non-polar solvents such as methylcyclohexane and heptane (Entries 1, 2). Conversely, use of aromatic solvents (i.e. Entries 3, 4) leads to a considerable drop in activity and an associated switch in product selectivity from oligomerisation towards PE formation. It has been reported previously that treatment of CrIII complexes with alkyl aluminium reagents in aromatic solvents, for example Cr(acac)3/AlMe3 in toluene [38], leads to the formation of reduced chromium(I) sandwich complexes of the type [Cr(η6-arene)2]+ [22], something that has been ascribed to account for the deactivation of homogeneous chromium oligomerisation systems in such solvents [29, 37]. Hence, it is likely that analogous CrI arene species are also formed during the activation of the oxide-bound chromium amide species, something that is consistent with the observed drop in activity.

2.2 Understanding the Nature and Catalytic Behaviour of Cr{N(SiMe3)2}x/SiO2−600

2.2.1 Raman Spectroscopic Analysis

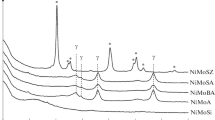

In order to understand the mode of action of this class of heterogeneous chromium-based olefin oligomerisation initiator, it is essential to develop insight into the nature of the surface-bound metal species. It is assumed that the Cr{N(SiMe3)2}3 precursor will react at the surface of SiO2−600 via the residual silanol sites eliminating the corresponding amine, HN(SiMe3)2. This type of reaction pathway is indeed supported by the Raman spectroscopic analysis of the resulting Cr{N(SiMe3)2}x/SiO2−600 material, which exhibits bands consistent with the presence of covalent Cr–O–Si linkages (1050 cm−1), and with the retention of amide ligands (Fig. 1) [39, 40].

2.2.2 Solid-State 29Si NMR Spectroscopic Analysis of Cr{N(SiMe3)2}x/SiO2−600

Although it was previously envisaged that for chromium-based systems, the operation of a metallacycle-based ethylene trimerisation reaction mechanism precluded the formation of longer chain oligo-/poly-meric products [4, 6, 41], more recent studies have since demonstrated that long-chain oligomers may also originate from a metallacyclic reaction manifold [42, 43]. In our work, however, the selective production of 1-hexene is not only accompanied by the formation of decenes, something that is likely to arise from secondary metallacycle-based ethylene/1-hexene co-trimerisation processes [43,44,45], but also polyethylene. These findings suggest that more than one catalytically active chromium species may be present at the surface of the partially dehydroxylated SiO2−600 catalyst support. Therefore, to investigate this possibility, the intrinsic paramagnetic nature of the oxide-immobilised chromium species has been exploited to help probe indirectly the nature of the supported transition metal species using solid-state 29Si NMR spectroscopy. This builds upon a previous study that demonstrated that magic-angle spinning (MAS) 29Si NMR spectroscopy provides information regarding the nature of the catalytically-relevant paramagnetic chromium species present in the related long-standing commercial “chromium” on silica Phillips ethylene polymerisation catalyst [46]. These experiments exploit the fact that the time constant for dipolar coupling relaxation increases with distance as r6, so the recovered magnetisation at time t after saturation will be that of the spins contained in a sphere of radius r corresponding to t1/6 [47]. Since dipolar coupling is typically transmitted over long distances by nuclear spin–spin diffusion, magic-angle spinning has the affect of averaging the secular component of the dipolar coupling between nuclear spins, which effectively quenches nuclear-spin diffusion. Together, this provides a cut-off above which nuclear-spin relaxation is observed, hence providing a measure of proximity between the paramagnetic chromium metal centre and 29Si nuclei [48].

To this end, a sample of the Cr{N(SiMe3)2}x/SiO2−600 pro-initiator was packed into an airtight rotor inside a nitrogen-filled glove box, and sealed under an inert atmosphere, prior to solid-state 29Si direct excitation (DE) MAS NMR spectroscopic analysis (Fig. 2). Compared to the longitudinal relaxation rates (T1−1) of 29Si nuclei present in SiO2−600 (T1−1 = 15.9 × 10−3 s−1) the presence of a paramagnetic CrIII species increased the T1−1 of the corresponding nuclei in Cr{N(SiMe3)2}x/SiO2−600 (T1−1 = 46.5 × 10−3 s−1), in addition to a fast-relaxing component (4.4 s−1). The latter results in line broadening of the resonances associated with the Q3 and Q2 environments (see Scheme 2), which were previously found to be in a 29:1 ratio by deconvolution (Gaussian distribution function) of the 29Si NMR spectrum of SiO2−600. Most notably, the resonance associated with the Q2 environments in Cr{N(SiMe3)2}x/SiO2−600 is broadened to such an extent that it is proposed to be lost in the baseline. Since T1 is directly proportional to the distance between the unpaired electron and the nucleus being observed by NMR spectroscopy (to the power of six) [49], it may be inferred that the 29Si nuclei corresponding to Q2 and Q3 sites are in close proximity to the supported chromium(III) species. In addition, the chromium(III) complex acts as a paramagnetic NMR shift reagent, such that the signal associated with the Q3 29Si nuclei is shifted to a lower frequency (Δδ = − 5 ppm) than that for the Q4 environment (Δδ = − 1 ppm). Taking these two observations together with the fact that the change in resonant frequency brought about by a through-space dipolar interaction is inversely proportional to the distance between the unpaired electron and the nucleus being observed by NMR spectroscopy (to the power of three) [50], we propose that Cr{N(SiMe3)2}3 has reacted with both Q2 and Q3 silanols at the surface of SiO2600 to give two different types of silica-bound species.

2.2.3 Cr{N(SiMe3)2}x/SiO2−600 Titration Experiment

To further confirm the presence of two different surface-bound chromium species, a titration experiment was conducted in which a sample of SiO2−600 (3.15 mmolOH g−1) was treated with a heptane solution of Cr{N(SiMe3)2}3 to a chromium loading of 0.71 wt%. This resulted in the evolution of HN(SiMe3)2 (1.03 molar equivalents) as a result of the reaction with the surface silanols. Since the ratio of Q2–Q3 silanol sites in SiO2−600 was determined to be 1:29, and the chromium metal loading of the resulting Cr{N(SiMe3)2}x/SiO2 pro-initiator was verified to be 0.71 wt% by ICP-OES analysis, it is proposed that Cr{N(SiMe3)2}3 reacts with both Q2 and Q3 surface silanol sites resulting in the formation of one or two Cr–O bonds, respectively, as demonstrated by evolution of 1.03 equivalents of amine (Scheme 2).

2.2.4 Impact of Support Calcination Temperature

Since there are at least two different types of supported chromium(III) species at the surface of Cr{N(SiMe3)2}x/SiO2−600, which result from the presence of both Q2 and Q3 sites in a ratio of 1:29 for SiO2−600, a second catalytic system was prepared using silica calcined at 200 rather than 600 °C, in order to increase the relative concentration of Q2 silanols with respect to Q3. The effects of calcination of the SiO2 support material were explored by thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) and solid-state 29Si NMR spectroscopy. The latter technique provides direct quantitative information on the relative changes in silanol content and nature as a function of temperature.

Solid-state 29Si DE MAS NMR spectroscopy was used to quantify the change in the relative proportions of the Q2 (− 91 ppm), Q3 (− 99 ppm) and Q4 (− 110 ppm) sites of the Aeroperl 300/30 silica as a function of calcination temperature (Fig. 3; Table 4), with spectral assignments made in accordance with a previous NMR spectroscopic study [51]. The deconvoluted 29Si NMR spectra demonstrate that as the temperature of calcination is raised, the concentration of Q2, Q3 and vicinal silanols is attenuated. Nevertheless, although both the SiO2−200 and SiO2−600 materials exhibit three resonances in their 29Si NMR spectra, it is impossible to discriminate between vicinal and Q3 silanols as their characteristic resonance frequencies overlap at ~ − 100 ppm [51]. However, since it is well-established that vicinal silanols condense at calcination temperatures of 400 °C and above [52, 53], it is proposed that the sample calcined at 200 °C (SiO2−200) retains some vicinal silanol functionalities, as well as both Q2 and Q3 silanol sites. Contrastingly, the SiO2−600 material revealed that both Q2 and Q3 sites are present.

In order to further differentiate the nature of the reactive surface silanol species present on the silica surfaces following calcination, a TGA study was undertaken in parallel. As expected from previous reports concerning a number of different silicas [53], the calcination of Aeroperl 300/30 occurs over four distinct temperature regimes, as evidenced by TGA/DTG (Fig. 4, I–IV): loss of physisorbed water (dehydration) between 50 and 120 °C (I) and 120–190 °C (II); condensation of vicinal, isolated (Q3) and geminal (Q2) silanols (i.e. dehydroxylation) between ~ 190 and 450 °C (III); and further dehydroxylation of Q2 and Q3 silanols above 500 °C (IV). Consequently, the silica sample calcined at 200 °C (SiO2−200) may be regarded as essentially dehydrated silica, retaining a significant concentration of Q2, Q3 and vicinal silanol functionalities in accordance with the solid-state NMR spectroscopic data (Table 4). In contrast, from combining the TGA and NMR spectroscopic studies, the surface of the SiO2−600 material is found to be both dehydrated and partially dehydroxylated, thus leaving it with primarily Q3 silanol groups together with Q4 sites and a low concentration of residual Q2 species (i.e. Q3:Q2 = 29:1). These differences in the nature and hence reactivity of the surfaces of SiO2−200 and SiO2−600 will directly lead to the generation of different chromium species following reaction of each of these materials under anhydrous conditions with Cr{N(SiMe3)2}3.

Subsequently, SiO2−200 was treated with Cr{N(SiMe3)2}3 using an analogous procedure to that used for the preparation of Cr{N(SiMe3)2}x/SiO2−600, and the catalytic performance of the resulting material evaluated in combination with MMAO-12 under standard test conditions (Table 5). Not only is the resulting Cr{N(SiMe3)2}x/SiO2−200 system a much less active initiator (Entry 1), but it also shows a dramatic switch in selectivity towards the formation of PE compared with the system prepared using SiO2−600 (Entry 2). This is consistent with previous preliminary observations made by Monoi and co-workers [18, 54].

Since the ratio of Q2:Q3 silanols increases at higher support calcination temperatures, it is proposed that chromium amide species bound to Q2 sites favour PE formation (through a classical Cossee-Arlman chain growth mechanism [55,56,57]), whereas Q3-bound chromium species mediate ethylene trimerisation via a supported variant of the metallacycle mechanism (Scheme 1) [6], as shown in Scheme 3. Parallels may therefore be drawn between the heterogeneous Cr{N(SiMe3)2}x/SiO2−600 pro-initiator described herein, the more well-established homogeneous Cr-based ethylene trimerisation systems [1, 3], and indeed the supported “Phillips” Cr/SiO2 polymerisation catalyst [58, 59].

3 Conclusions

Preliminary catalyst screening of Cr{N(SiMe3)2}x/oxide−600-based oligomerisation pro-initiators demonstrated that catalytic performance is intimately linked to the nature of the oxide support, aluminium activator, and organic diluent. In our hands the best performing ethylene trimerisation initiator comprise Cr{N(SiMe3)2}x/SiO2−600 and MMAO-12 operated as a slurry in heptane. Based on a combined TGA and solid-state 29Si NMR spectroscopic study, two distinct silica-immobilised chromium species are present at the surface of Cr{N(SiMe3)2}x/SiO2−600. It is proposed that in combination with the aluminium activator MMAO-12, =SiO2CrN(SiMe3)2 species resulting from reaction of Cr{N(SiMe3)2}3 with Q2 silanol sites, are responsible for polyethylene formation, while selective ethylene trimerisation is mediated by ≡SiOCr{N(SiMe3)2}2 derived from Q3 silanols.

4 General Experimental

Unless stated otherwise, all manipulations were carried out under an atmosphere of dry nitrogen using standard Schlenk line techniques or in an Innovative Technologies nitrogen-filled glovebox. All glassware was oven-dried before use. Dry solvents were obtained from an Innovative Technologies SPS facility and degassed prior to use by three freeze-pump-thaw cycles, unless otherwise stated. Pentane, heptane, methylcyclohexane and nonane were dried over CaH2, distilled and degassed. Chlorobenzene was dried over P2O5, distilled and degassed. Evonik Aeroperl 300/30 SiO2 (described herein as SiO2), Sigma Aldrich SiO2–Al2O3 Grade 135 catalyst support (13 wt% Al; described herein as SiO2–Al2O3) [60], and Alfa Aesar γ-Al2O3 (1/8″ pellets ground and sieved to < 250 μm; described herein as γ-Al2O3) were used as catalyst supports. Ethylene (BOC) was passed through a moisture scrubbing column containing molecular sieves (Sigma Aldrich; 3A, 4A, and 13X) that had previously been activated at 400 °C for three hours under dynamic vacuum (i.e. 0.05 mbar), before being cooled to RT and stored under ethylene. All other chemicals, unless stated, were obtained from Sigma Aldrich or Alfa Aesar and used without further purification. Modified methyl aluminoxane-12 (MMAO-12); Sigma Aldrich, 7 wt% solution in toluene; approx. molecular formula: [(CH3)0.95(n-C8H17)0.05AlO]n.

Isobutyl aluminoxane (IBAO) was prepared according to a modification of a previously disclosed protocol [61]. Distilled, deionised water (20 mL) was degassed by purging with N2 at a rate of 2 mL s−1. An ampoule was charged with iBu3Al (25 wt% solution in toluene; 25 mL, 5.3 g, 0.0267 moles), which was then cooled in an ice bath to 4 °C. An aliquot (0.85 molar equivalents) of distilled, deionised and degassed H2O (0.41 mL, 0.0228 moles) was added cautiously drop-wise to the cool, stirring solution of iBu3Al. The reaction mixture was then allowed to warm to RT, and stirred for a further 10 h. The resulting colourless solution was stored at RT in an ampoule under N2 and used, as prepared, without further analysis.

The complex Cr{N(SiMe3)2}3 was synthesised according to the protocol previously reported by Bradley and isolated as a dark green air-/moisture-sensitive solid, which was handled under an inert atmosphere [62]. Anal. Calc. for C18H54N3CrSi6: C, 40.55; H 10.21; N 7.88 Found: C, 40.51; H, 10.30; N, 7.71%. IR (KBr, Nujol νmax/cm−1) 1263, 1254, 910, 860, 794, 760, 708, 678, and 619 (lit. [40], 1260, 1250, 902, 865, 840, 820, 790, 758, 708, 676 and 620). Raman (solid, 532 nm, νmax/cm−1) 2956, 2898, 1260, 1240, 904, 855, 805, 728, 707, 679, 636, 424 and 382.

Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) specific surface area analysis (SSA) and Barrett–Joyner–Halenda (BJH) pore size and volume analyses were completed using a Micromeritics instrument. Thermogravimetric (TGA) analyses were completed using a Perkin Elmer Pyris 1 TGA, coupled to a Hiden HPR 20 MS unit purged with helium gas. Solid-state 1H (400 MHz frequency; 13 KHz rotation rate), 27Al (104 MHz; 13 KHz spinning rate) magic spinning angle (MAS) and 29Si (79 MHz; 6–8 KHz rotation rate) direct excitation (DE) nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopic analyses (Varian VNMRS) were completed with samples packed into an airtight rotor inside a nitrogen-filled glove box, and sealed under an inert atmosphere. Solid-state NMR samples were referenced to external Si(CH3)4 (1H, 29Si) or 1M Al(NO3)3(aq) (27Al). The 29Si NMR resonances attributed to geminal (Q2), isolated (Q3) and bulk silica (Q4) were quantified using a Gaussian distribution curve fit using MestreNova (MestreLab). Spin–lattice relaxation times were measured using a saturation-recovery method. A five-parameter fit was used to model the result, including a two-component exponential recovery plus baseline. Raman spectroscopy was conducted using a Horiba LabRAM-HR spectrometer equipped with a 532 nm frequency-doubled Nd:YAG laser and a 1800 lines/mm grating. The samples were loaded into a standard glass J-Young NMR tube inside a nitrogen-filled glove box and sealed under an inert atmosphere.

Gas chromatographic (GC) analyses were performed on a Perkin Elmer Clarus 400 system equipped with a PONA (50 m × 0.20 mm × 0.50 μm) capillary column. Analytes were detected using a flame ionisation detector (FID). The oven temperature was maintained at 40 °C for 10 min, before the temperature was increased to 170 °C at a rate of 20 °C min−1. This temperature was maintained for 5 min. Subsequently, the column was heated further to 300 °C, again at a rate of 20 °C min−1. The temperature was maintained at 300 °C for 12 min before the system was allowed to cool to 40 °C. The GC-FID analysis total run time was 40 min.

5 General Procedures for Calcination of Oxide Support Materials

Using a variation of a previously reported methodology [18], a quartz tube (20 mm I.D.) fitted with a porous quartz frit was sequentially charged with previously acid-washed quartz wool (H. M. Baumbach) and the oxide-based catalyst support (5.0 g) to form a solid plug. The quartz tube was then placed vertically inside a tube furnace, such that the oxide was centred in the furnace; a thermocouple was attached to the outside of the quartz tube and located level with the centre of the oxide bed. Oxygen-free nitrogen gas, previously dried by passage through a drying column consisting of CaCl2 and P2O5, was passed down through the oxide bed (1 mL s−1), exiting the system via a silicon oil bubbler. The oxide was heated to 600 °C (ramp rate = 10 °C min−1) and then maintained at 600 °C for 24 h under a flow of N2. Subsequently, the calcined material was allowed to cool to room temperature under a flow of N2, before being transferred under vacuum into a glovebox without exposure to air. Supports are classified by the temperature at which they were calcined, e.g. SiO2−600 denotes silica calcined at 600 °C for 24 h under a flow of N2. The SiO2−200 support material was prepared from SiO2 using an analogous protocol, but being held at only 200 °C for 24 h.

6 General Analyses of Oxide Support Materials

6.1 Specific Surface Area and Pore Volume/Size Analysis

The BET specific surface area (SSA) and BJH pore volume/size distributions for Evonik Aeroperl 300/30 fumed SiO2, Sigma Aldrich SiO2–Al2O3, and Alfa Aesar γ-Al2O3 catalyst supports have been determined (Table 6). A sample of each untreated oxide-based support was degassed at 140 °C with a nitrogen purge for 1 h, prior to BET specific surface area and isotherm measurements.

6.2 Solid-State NMR Spectroscopic Analysis of Oxide Supports

Evonik Aeroperl 300/30 fumed SiO2, Sigma Aldrich SiO2–Al2O3 and Alfa Aesar γ-Al2O3 catalyst supports were analysed using solid-state 1H, 27Al and 29Si DE MAS NMR spectroscopy.

6.2.1 Evonik Aeroperl 300/30 Fumed SiO2

1H DE MAS NMR (400 MHz, solid, 13 KHz rotation, 1 s recycle, 160 repetitions) δ = 3.7. 29Si DE MAS NMR (79 MHz, solid, 6 KHz rotation, 120 s recycle, 547 repetitions) δ = − 91 (Q2), − 100 (Q3), − 110 (Q4).

6.2.2 Sigma Aldrich Grade 135 SiO2–Al2O3

1H DE MAS NMR (400 MHz, solid, 13 KHz rotation, 1 s recycle, 160 repetitions) δ = 7.0, 5.0. 27Al DE MAS NMR (104 MHz, solid, 13 KHz rotation, 0.2 s recycle, 750 repetitions) δ = 56 (AlO4), 4 (AlO6). 29Si DE MAS NMR (79 MHz, solid, 6 KHz rotation, 30 s recycle, 1824 repetitions) δ = − 91 (Q2), − 102 (Q3), − 110 (Q4).

6.2.3 Alfa Aesar γ-Al2O3 (Powder Sieved to < 250 μm)

1H DE MAS NMR (400 MHz, solid, 13 KHz rotation, 1 s recycle, 160 repetitions) δ = 5.0. 27Al DE MAS NMR (104 MHz, solid, 13 KHz rotation, 0.2 s recycle, 3950 repetitions) δ = 64 (AlO4), 5 (AlO6).

The thermogravimetric profile (TGA/DTG) of SiO2 was measured between 30 and 600 °C, at a rate of 30 °C min1, and then held at 600 °C for 24 h.

6.3 Analysis of SiO2−200

29Si DE MAS NMR (79 MHz, solid, 6 KHz rotation, 120 s recycle, 500 repetitions) δ = − 91 (Q2), − 100 (Q3), − 109 (Q4).

6.4 Analysis of SiO2−600

1H DE MAS NMR (400 MHz, solid, 6 KHz rotation, 5 s recycle, 32 repetitions) δ = 1.9. 29Si DE MAS NMR (79 MHz, solid, 6 KHz rotation, 120 s recycle, 500 repetitions) δ = − 91 (Q2), − 99 (Q3), − 109 (Q4). Raman (solid, 532 nm, νmax/cm−1): 455.

6.4.1 Estimation of Residual Silanol Concentration for SiO2−600 by Titration Para-Tolylmagnesium Bromide

A Schlenk was charged with SiO2−600 (0.2116 g) inside a glovebox and sealed under N2. The calcined material was suspended in heptane (10 mL), stirred at 200 rpm via a Teflon-coated magnetic stirrer bar and then cooled to 5 °C using an ice/water bath, prior to being reacted with a Et2O solution of para-tolylmagnesium bromide (1.8 mL, 2 M, 3.6 mmol), which was added slowly via a syringe. The stirred suspension was then allowed to warm to RT. After 1 h, the reaction was cooled to 0 °C using an ice/water bath and quenched with propanal (5 mL, 69.7 mmol), before nonane (1.0 mL, 5.6 mmol) was added as an internal standard. An aliquot of the organic phase was filtered through a plug of cotton wool/Celite and subsequently analysed by GC-FID. The concentration of residual silanols was determined, from the quantity of liberated toluene, to be 3.15 mmolOH g−1.

6.4.2 Quantification of Amine Liberated Through Reaction of SiO2−600 with Cr{N(SiMe3)2}3

An ampoule was charged with freshly calcined SiO2−600 (2.89 g, 0.048 moles) inside a glovebox and sealed under N2. The ampoule was connected to a Schlenk line via a vacuum transfer side arm. A stock solution of Cr{N(SiMe3)2}3 in heptane (50.5 mL, 0.0078 M, 0. 39 mmol; Cr/SiO2 = 0.71 wt%) was added portion-wise to the reaction vessel using a dry, degassed syringe. The resulting white solid, suspended in a green solution, was stirred for 10 h at RT, by which time the solution had become colourless and the solid green. ICP-OES analysis confirmed no residual chromium in the organic phase. The combined reaction mixture was frozen at − 196 °C and the reaction vessel evacuated (0.1 mbar). Upon thawing, all volatile components were isolated by vacuum transfer to afford a colourless organic solution. Subsequently nonane (1.0 mL 5.6 mmol) was added to this solution, before an aliquot of the resulting mixture was collected, passed through a plug of cotton wool/Celite, and analysed by GC-FID to quantify the amount of HN(SiMe3)2 liberated on reaction of Cr{N(SiMe3)2}3 with a known quantity of SiO2−600. The mole ratio of Cr : HN(SiMe3)2 was determined to be 1:1.03.

6.5 General Protocol for the Preparation of the Oxide-Supported Chromium Catalysts

A Schlenk was charged with the partially dehydroxylated oxide support (2.0 g) inside a glove box and sealed under N2. The Schlenk was connected to a vacuum line, evacuated and re-filled with dry N2 three times, then charged with a stock solution of Cr{N(SiMe3)2}3 in heptane (0.0078 M, 35 mL, 0.27 mmol; 0.71 wt% Cr). The reaction mixture was stirred at 500 rpm via a Teflon-coated magnetic stirrer bar for 10 h at RT. At the end of this period, the solution had changed from green to colourless, while the solid had turned green. All volatile components were then removed in vacuo and the resulting green solid transferred into a nitrogen-filled glove box and stored at ambient temperature. The extent of Cr uptake was assessed via ICP-OES analysis of the impregnated oxide materials.

6.6 General Protocol for the Determination of Chromium Loading of Cr{N(SiMe3)2}x/Oxide by ICP-OES

A known mass of the Cr{N(SiMe3)2}x/oxide (0.0063 g; 0.71 wt% Cr) was charged into a polypropylene vial under air, and suspended in an aqueous solution of HCl (1.5 mL, 37% w/w, 12.7 mmol). Following 10 h standing at RT the mixture was carefully diluted with deionised water (13.5 mL), prior to ICP-OES analysis. The ICP-OES instrument was calibrated using standard aqueous solutions of Cr(NO3)3·6H2O.

6.7 Analysis of Cr{N(SiMe3)2}x/SiO2−600

The ethylene trimerisation pro-initiator was analysed using both Raman and solid-state 29Si NMR spectroscopies.

1H DE MAS NMR (400 MHz, solid, 6 KHz rotation, 5 s recycle, 32 repetitions) δ = 0.15. 29Si DE MAS NMR (79 MHz, solid, 8 KHz rotation, 1 s recycle, 56,976 repetitions) δ = − 104 (Q3), − 109 (Q4). Raman (solid, 532 nm, νmax/cm−1) 2960, 2899, 1252, 854, 726, 807, 726, 637, 423 and 385.

6.8 Typical Ethylene Oligomerisation Procedure

A rigorously cleaned 150 mL stainless steel Parr autoclave (fitted with a pressure gauge, a bursting disk, and an internal K-type thermocouple) was taken into the glovebox under dynamic vacuum (~ 0.1 mbar) for 10 h. The vessel was charged with Cr{N(SiMe3)2}x/oxide (0.71 wt% Cr/oxide, 27 μmol Cr) and sealed under N2. The vessel was then connected to a Schlenk line and charged with a solution containing heptane (60 mL), nonane (1.0 mL) and MMAO-12 (7 wt% solution in toluene; 0.18 mL, 0.041 mmol) under a flow of N2 via a cannula. The autoclave was sealed under N2, before being purged with ethylene (1 mL s−1) for 10 s and then sealed. The contents of the reactor were cautiously heated to 120 °C using an external solid-state electrical band heater, whilst being agitated at 500 rpm using a customised magnetically-coupled overhead stirrer fitted with a turbine-type four-blade impeller. On reaching 120 °C the reactor was then pressurised with ethylene to 8 barg, prior to being isolated. After 30 min, the reaction vessel was cooled in a water/ice bath to 4 °C (30 min.) and then slowly vented inside a fume hood. An aliquot of the resulting liquid fraction was sampled, quenched with a 1:1 mixture of toluene and an aqueous solution of HCl (10% w/w). A sample of this organic phase was taken, filtered through a plug of cotton wool/Celite, before being analysed by GC-FID against the internal standard, nonane. Any residual white solid product (PE) was isolated via filtration, dried to constant weight at RT in air overnight (~ 10 h) and analysed using DSC.

References

McGuinness DS (2011) Chem Rev 111(3):2321–2341

Speiser F, Braunstein P, Saussine W (2005) Acc Chem Res 38:784–793

Dixon JT, Green MJ, Hess FM, Morgan DH (2004) J Organomet Chem 689(23):3641–3668

Manyik RM, Walker WE, Wilson TP (1977) J Catal 47(2):197–209

Briggs JR (1987) Process for trimerization. US4668838

Briggs JR (1989) J Chem Soc Chem Commun 11:674–675

Reagen WK, Conroy BK (1994) Chromium Compounds and Uses Thereof. US5198563A

Freeman JW, Buster JL, Knudsen RD (1999) Olefin production. US005856257

Lashier ME, Freeman JW, Knudsen RD (1996) Olefin production. US5543375

Carter A, Cohen SA, Cooley NA, Murphy A, Scutt J, Wass DF (2002) Chem Commun 8:858–859

Wass DF (2002) Olefin trimerisation using a catalyst comprising a source of chromium, molybdenum or tungsten and a ligand containing at least one phosphorous, arsenic or antimony atom bound to at least one (hetero)hydrocarbyl group. US6800702B2

Wright CMR, Williams TJ, Turner ZR, Buffet J-C, O’Hare D (2017) Inorg Chem Front 4(6):1048–1060

Varga V, Hodík T, Lamac M, Horacek M, Zukal A, Zilkova N Jr, Pinkas WOP J (2015) J Org Chem 777:57–66

Karbach FF, Severn JR, Duchateau R (2015) ACS Catal 5:5068–5076

Chen Y, Callens E, Abou-Hamad E, Merle N, White AJP, Taoufik M, Copéret C, Le Roux E, Basset JM (2012) Angew Chem Int Ed 51(47):11886–11889

Peulecke N, Müller BH, Peitz SE, Aluri BR, Rosenthal U, Wohl AI, Müller W, Al-Hazmi MH, Mosa FM (2010) Chem Catal Chem 2:1079–1081

Nenu CN, Weckhuysen BM (2005) J Chem Soc Chem Commun 14:1865–1867

Monoi T, Sasaki Y (2002) J Mol Catal A 187:135–141

Finiels A, Fajula F, Hulea V (2014) Catal Sci Technol 4:2412–2426

Bryliakov KP, Talsi EP (2012) Coord Chem Rev 256(23–24):2994–3007

Britovsek GJ, McGuinness DS (2016) Chem Eur J 22(47):16891–16896

McDyre L, Carter E, Cavell KJ, Murphy DM, Platts JA, Sampford K, Ward BD, Gabrielli WF, Hanton MJ, Smith DM (2011) Organometallics 30(17):4505–4508

McDyre LE, Hamilton T, Murphy DM, Cavell KJ, Gabrielli WF, Hanton MJ, Smith DM (2010) Dalton Trans 39(33):7792–7799

Thapa I, Gambarotta S, Korobkov I, Duchateau R, Kulangara SV, Chevalier R (2010) Organometallics 29(18):4080–4089

Brückner A, Jabor JK, McConnell AEC, Webb PB (2008) Organometallics 27(15):3849–3856

Tang S, Liu Z, Yan X, Li N, Cheng R, He X, Liu B (2014) Appl Catal A 481:39–48

McGuinness DS, Rucklidge AJ, Tooze RP, Slawin AMZ (2007) Organometallics 26:2561–2569

Agapie T, Labinger JA, Bercaw JE (2007) J Am Chem Soc 129(46):14281–14295

Blann K, Bollmann A, de Bod H, Dixon JT, Killian E, Nongodlwana P, Maumela MC, Maumela H, McConnell AE, Morgan DH, Overett MJ, Prétorius M, Kuhlmann S, Wasserscheid P (2007) J Catal 249(2):244–249

Chen EYX, Marks TJ (2000) Chem Rev 100(4):1391–1434

Ehm C, Cipullo R, Budzelaar PHM, Busico V (2016) Dalton Trans 45:6847–6855

Wright WRH, Batsanov AS, Howard JAK, Tooze RP, Hanton MJ, Dyer PW (2010) Dalton Trans 39:7038–7045

Jabri A, Mason CB, Sim Y, Gambarotta S, Burchell TJ, Duchateau R (2008) Angew Chem Int Ed 47:9717–9721

Vidyaratne I, Nikiforov GB, Gorelsky SI, Gambarotta S, Duchateau R, Korobkov I (2009) Angew Chem Int Ed 48:6552–6556

Hagimoto H, Shiono T, Ikeda T (2004) Macromol Chem Phys 205:19–26

Tanaka R, Kawahara T, Shinto Y, Nakayama Y, Shiono T (2017) Macromolecules 50:5989–5993

Kulangara SV, Haveman D, Vidjayacoumar B, Korobkov I, Gambarotta S, Duchateau R (2015) Organometallics 34:1203–1210

Angelescu E, Nicolau C, Simon Z (1966) J Am Chem Soc 88(17):3910–3912

Stavropoulos P, Bryson N, Youinou MT, Osborn JA (1990) Inorg Chem 29(10):1807–1811

Alyea EC, Bradley DC, Copperthwaite RG (1972) J Chem Soc, Dalton Trans 14:1580–1584

van Rensburg WJ, Grové C, Steynberg JP, Stark KB, Huyser JJ, Steynberg PJ (2004) Organometallics 23:1207–1222

Tomov AK, Gibson VC, Britovsek GJP, Long RJ, van Meurs M, Jones DJ, Tellmann KP, Chirinos JJ (2009) Organometallics 28:7033–7040

Overett MJ, Blann K, Bollmann A, Dixon JT, Haasbroek D, Killian E, Maumela H, McGuinness DS, Morgan DH (2005) J Am Chem Soc 127:10723–10730

Do LH, Labinger JA, Bercaw JE (2012) Organometallics 31:5143–5149

Zilbershtein TM, Kardash VA, Suvorova VV, Golovko AK (2014) Appl Catal A 475:371–378

Chudek JA, Hunter G, McQuire GW, Rochester CH, Smith TFS (1996) J Chem Soc Faraday Trans 92(3):453–460

Hartman JS, Sherriff BL (1991) J Phys Chem 95(20):7575–7579

Devreux F, Boilot JP, Chaput F, Sapoval B (1990) Phys Rev Lett 65(5):614–617

Appendix V- (2017) Relaxation by dipolar interaction between two Spins A2 - Bertini, Ivano. In: Luchinat C, Parigi G, Ravera E (eds) Nmr of paramagnetic molecules (Second Edition). Elsevier, Boston, pp 471–475

Bertini I, Luchinat C, Parigi G, Ravera E (2017) Chap. 2 - the hyperfine shift. Nmr of Paramagnetic Molecules (Second Edition). Elsevier, Boston, pp 25–60

Vansant EF, Voort PVD, Vrancken KC (1995) Chapter 5 the distribution of the silanol types and their desorption energies, In: Vansant EF, Voort PVD, Vrancken KC (eds) Studies in surface science and catalysis, vol 93. Elsevier, pp 93–126

Zhuravlev LT (2000) Colloids Surf A 173:1–38

Vansant EF, Voort PVD, Vrancken KC (1995) Chapter 3 the surface chemistry of silica, In: Vansant EF, Voort PVD, Vrancken KC (eds) Studies in surface science and catalysis, vol 93. Elsevier, Amsterdam, pp 59–77

Monoi T, Ikeda H, Ohira H, Sasaki Y (2002) Polym J 34(6):461–465

Cossee P (1964) J Catal 3(1):80–88

Arlman EJ (1964) J Catal 3(1):89–98

Arlman EJ, Cossee P (1964) J Catal 3(1):99–104

Brown C, Krzystek J, Achey R, Lita A, Fu R, Meulenberg RW, Polinski M, Peek N, Wang Y, Burgt LJ, Profeta S Jr, Stiegman AE, Scott SL (2015) ACS Catal 5:5574–5583

McDaniel MP (2010) Adv Catal 53:123–606

Debecker DP, Stoyanova M, Rodemerck U, Léonard A, Su BL, Gaigneaux EM (2011) Catal Today 169(1):60–68

Edwards DN, Briggs JR, Marcinkowsky AE, Lee KH (1988) Process for the preparation of aluminoxanes. US4772736

Bradley DC, Copperthwaite RG, Extrine MW, Reichert WW, Chisholm MH (1972) J Chem Soc Dalton Trans 18:112–120

Acknowledgements

This work was co-sponsored by the EPSRC and Johnson Matthey PLC as part of an I-CASE PhD studentship (Reference number: 1353008). The authors greatly appreciate assistance from Prof. A. Beeby, and Dr. E. Unsworth (Durham), D. Scott and R. Fleming (Johnson Matthey) in the collection of Raman and inductively coupled plasma-optical emission spectroscopic data, respectively, and D. Carswell for thermogravimetric measurements. BET specific surface area and BJH pore size and volume analyses were completed by S. Ridley and R. Fletcher of Johnson Matthey Process Technologies (Chilton). CHN analyses were carried out by S. Boyer (London Metropolitan University). The authors would also like to thank Johnson Matthey for their permission to publish this work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Lamb, M.J., Apperley, D.C., Watson, M.J. et al. The Role of Catalyst Support, Diluent and Co-Catalyst in Chromium-Mediated Heterogeneous Ethylene Trimerisation. Top Catal 61, 213–224 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11244-018-0891-8

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11244-018-0891-8