Abstract

Coronal holes are the darkest and least active regions of the Sun, as observed both on the solar disk and above the solar limb. Coronal holes are associated with rapidly expanding open magnetic fields and the acceleration of the high-speed solar wind. This paper reviews measurements of the plasma properties in coronal holes and how these measurements are used to reveal details about the physical processes that heat the solar corona and accelerate the solar wind. It is still unknown to what extent the solar wind is fed by flux tubes that remain open (and are energized by footpoint-driven wave-like fluctuations), and to what extent much of the mass and energy is input intermittently from closed loops into the open-field regions. Evidence for both paradigms is summarized in this paper. Special emphasis is also given to spectroscopic and coronagraphic measurements that allow the highly dynamic non-equilibrium evolution of the plasma to be followed as the asymptotic conditions in interplanetary space are established in the extended corona. For example, the importance of kinetic plasma physics and turbulence in coronal holes has been affirmed by surprising measurements from the UVCS instrument on SOHO that heavy ions are heated to hundreds of times the temperatures of protons and electrons. These observations point to specific kinds of collisionless Alfvén wave damping (i.e., ion cyclotron resonance), but complete theoretical models do not yet exist. Despite our incomplete knowledge of the complex multi-scale plasma physics, however, much progress has been made toward the goal of understanding the mechanisms ultimately responsible for producing the observed properties of coronal holes.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Coronal holes are regions of low density plasma on the Sun that have magnetic fields opening freely into the heliosphere. Because of their low density, coronal holes tend to be the regions of the outer solar atmosphere that are most prone to behaving as a collisionless plasma. Ionized atoms and electrons flow along the open magnetic fields to form the highest-speed components of the solar wind.

The term “coronal hole” has come to denote several phenomena that may not always refer to the same regions. First, the darkest patches on the solar surface, as measured in ultraviolet (UV) and X-ray radiation, are called coronal holes. Second, the term also applies to the lowest-intensity regions measured above the solar limb, seen either during a total solar eclipse or with an occulting coronagraph. Third, there is a more theoretical usage that equates coronal holes with all open-field footpoints of time-steady solar wind flows. There are good reasons why these three ideas should be related to one another, but the overlap between them is not complete. To avoid possible confusion, this paper will mainly use the first two observational definitions, with the third one being only partly applicable.

During times of low solar activity, when the Sun’s magnetic field is dominated by a rotationally-aligned dipole component, there are large coronal holes that cover the north and south polar caps of the Sun. In more active periods of the solar cycle, coronal holes can exist at all solar latitudes, but they may only persist for several solar rotations before evolving into different magnetic configurations.

Despite not being as visually spectacular as active regions, solar flares, or coronal mass ejections (CMEs), coronal holes are of abiding interest for (at least) three main reasons.

-

1.

The extended corona and solar wind connected with coronal holes tends to exist in an ambient time-steady state, at least in comparison with other regions. This makes coronal holes a natural starting point for theoretical modeling, since it often makes sense to begin with the simplest regions before attempting to understand more complex and variable structures.

-

2.

Coronal hole plasma has the lowest density, which makes it an optimal testbed for studies of collisionless kinetic processes that are the ultimate dissipation mechanisms in many theories of coronal heating. Other regions tend to have higher densities and more rapid Coulomb collisions, and thus the unique signatures of the kinetic processes (in their particle velocity distributions) are not as straightforward to measure as in coronal holes.

-

3.

Coronal holes and their associated high-speed wind streams are also responsible for a fraction of major geomagnetic storms at 1 AU. Corotating interaction regions (CIRs) form when fast and slow wind streams collide with one another, and the subsequent interaction between these structures and the Earth’s magnetosphere can give rise to long-lasting fluxes of energetic electrons.

This paper reviews measurements of the plasma properties of coronal holes and how these measurements have been used to put constraints on theoretical models of coronal heating and solar wind acceleration. There have been several earlier reviews that have focused mainly on the topic of coronal holes, including Zirker (1977), Suess (1979), Harvey and Sheeley Jr (1979), Parker (1991), Kohl and Cranmer (1999), Hudson (2002), Cranmer (2002a), Ofman (2005), de Toma and Arge (2005), Jones (2005), and Wang (2009). Interested readers are urged to survey these other reviews in order to fill in any gaps in topical coverage in the present paper.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 gives a brief history of the discovery and early years of research on coronal holes. Section 3 summarizes the observations and derived plasma properties of “on-disk” coronal holes (i.e., primarily using the definition of holes as dark patches on the solar surface at UV and X-ray wavelengths). Section 4 reviews the measurements of “off-limb” coronal holes and describes our current knowledge of how these structures are linked to various kinds of solar wind streams measured in situ. Section 5 discusses a broad range of possible theoretical explanations for how the plasma in coronal holes is heated and how the solar wind in these regions is accelerated. Section 6 concludes this paper with a few words about how the study of coronal holes helps to improve our wider understanding of heliophysics, astrophysics, and plasma physics.

2 Historical Overview

Although the term “coronal hole” was not first used until the middle of the 20th century, people have reported the existence of visible features associated with the Sun’s corona — seen during total eclipses — for centuries (see, e.g., Wang and Siscoe, 1980; Vaquero, 2003). A popular astronomy book from the first decade of the 20th century (Serviss, 1909) contained clear descriptions of coronal streamers, eruptive prominences, and polar plumes in coronal holes. The following description of the latter, from an eclipse in 1900, conveys that early speculation may sometimes be prescient:

“The sheaves of light emanating from the poles look precisely like the ‘lines of force’ surrounding the poles of a magnet. It will be noticed in this photograph that the corona appears to consist of two portions: one comprising the polar rays just spoken of, and the other consisting of the broader, longer, and less-defined masses of light extending out from the equatorial and middle-latitude zones. Yet even in this more diffuse part of the phenomenon one can detect the presence of submerged curves bearing more or less resemblance to those about the poles. Just what part electricity or electro-magnetism plays in the mechanism of solar radiation it is impossible to say, but on the assumption that it is a very important part is based the hypothesis that there exists a direct solar influence not only upon the magnetism, but upon the weather of the earth” (Serviss, 1909).

The first quantitative observations of coronal holes were made by Waldmeier (1956, 1957) at the Swiss Federal Observatory in Zürich. These features were identified as long-lived regions of negligible intensity in coronagraphic (off-limb) images of the 5303 Å green emission line (see also Waldmeier, 1975, 1981). Waldmeier called the features that appeared more-or-less circular when projected onto the solar disk Löcher (holes), and the more elongated features were called Kanal (channels) or Rinne (grooves).

In off-limb eclipse and coronagraph images, the darkest coronal hole regions are surrounded by brighter and more complex streamers. These wispy structures appear to be connected to closed magnetic field lines at the solar surface, but they are often stretched upwards to an elongated cusp-like point, with thin “stalks” of radial rays at the top. For this reason their appearance was likened to a pointed German helmet (or a brush-topped Greek or Roman helmet), and the common phrase helmet streamers is often seen. The earliest studies of coronal morphology tended to concentrate more on streamers than coronal holes because the former are significantly easier to see than the latter (see, e.g., Miller, 1908; Mitchell, 1932; Newkirk Jr, 1967; Pneuman, 1968). Piddington (1972) outlined some early ideas about the global structure of the “quiet” (i.e., solar minimum) corona. Figure 1 compares an adaptation of J. H. Piddington’s sketch of the quiet corona to a more recent photograph from another eclipse around solar minimum.

Left: Adaptation of a sketch of the quiet solar corona made by Piddington (1972), based on prior drawings (Waldmeier, 1955) and photographs (Gold, 1955) of the 30 June 1954 eclipse. Right: Contrast-adjusted eclipse image taken with the POISE instrument on 26 February 1998, in Westpunt, Curaçao. The original image was made available courtesy of the High Altitude Observatory (HAO), University Corporation for Atmospheric Research (UCAR), Boulder, Colorado. UCAR is sponsored by the National Science Foundation.

As the quality of the observations improved, coronal holes became objects of study in their own right. The largest coronal holes were observed to contain fine thread-like polar plumes that appear to follow the superradially expanding open magnetic field lines above the solar limb (Saito, 1958; Stoddard et al., 1966; Newkirk Jr and Harvey, 1968). These elongated structures were found to correlate with bright chromospheric faculae on the surface (e.g., Harvey, 1965) and with longer extensions for the small jet-like spicules that continually rise and fall above the limb (Lippincott, 1957; Beckers, 1968).

Coronal holes were essentially re-discovered in the late 1960s and early 1970s as discrete dark patches on the X-ray and ultraviolet solar disk. Newkirk Jr (1967) reviewed some of the earliest rocket-based measurements in the extreme UV, and Tousey et al. (1968) discussed how the UV emission was “usually weaker over the poles” in images from a series of rocket flights between 1963 and 1967 (around solar minimum). These regions on the solar disk came to be called coronal holes in parallel with the earlier off-limb usage. Munro and Withbroe (1972) analyzed OSO-4 observations to conclude that both the density and electron temperature were lower in these dark regions. In 1973 and 1974, solar instruments on the Apollo telescope mount (ATM) on Skylab confirmed many earlier ideas about coronal holes with data significantly better in quantity and quality (Huber et al., 1974; Kahler, 2000).

In addition to the large north and south polar holes, there were also found to be smaller coronal holes that exist at lower latitudes (often at times other than solar minimum). Sometimes the largest coronal holes can exhibit thin “peninsulas” that jut out from the main regions. Harvey and Recely (2002) called these regions “polar lobes.” Notable examples have been the so-called “Boot of Italy” seen by Skylab in 1974 (e.g., Zirker, 1977) and the “Elephant’s Trunk” seen by SOHO in 1996 (Del Zanna and Bromage, 1999). A third example, from December 2000, is shown in Figure 2.

Additional insights came from the fusion of spectroscopy and coronagraphic occultation. Inspired by rocket-borne UV observations of the extended corona during a solar eclipse in March 1970, Kohl et al. (1978) developed a UV coronagraph spectrometer to measure the profile shape of the bright H I Lyα emission line at 1216 Å. This line is sensitive to several key properties of the velocity distribution of coronal protons, and thus these observations could be used to begin distinguishing proton temperatures from electron temperatures in the collisionless outer regions of coronal holes (see Section 4.3). The rocket-borne UV coronagraph spectrometer was launched three times (in 1979, 1980, and 1982), and the results included the first direct evidence for proton heating and supersonic outflow in coronal holes (Kohl et al., 1980; Strachan et al., 1993; Kohl et al., 2006).

The fact that coronal holes coincide with regions of open magnetic field that expands out into interplanetary space was realized during the first decade of in situ solar wind observations (e.g., Wilcox, 1968; Altschuler et al., 1972; Hundhausen, 1972). Noci (1973) made a theoretical argument, on the basis of measured wave fluxes and heat conduction, that coronal holes should have the largest solar wind kinetic energy fluxes (i.e., the highest speeds). Pneuman (1973) argued that coronal holes need not have lower energy deposition than closed-field regions (as is suggested by the lower intensities of coronal holes) if the solar wind carries away much of that energy. Krieger et al. (1973) utilized X-ray sounding rocket images to identify a large coronal hole as the solar source of a strong high-speed stream as measured by the Pioneer 6 and Vela spacecraft. Around this time it was also realized that coronal holes and high-speed wind streams are also responsible for a fraction of the geomagnetic storms seen at 1 AU (Bell and Noci, 1973; Neupert and Pizzo, 1974; Bell and Noci, 1976; see also Tanskanen et al., 2005 and Zhang et al., 2007). Although there is still no complete understanding of which types of solar wind flow are connected with which types of coronal structures, the causal link between the largest coronal holes and high-speed streams remains firm (see also Section 4.1).

3 Properties of On-Disk Coronal Holes

The traditional observational distinction between coronal holes and their surroundings (i.e., active regions and “quiet Sun”) is that coronal holes have the lowest emission in the UV and X-ray. This definition must be amended, however, to exclude filaments (which are often dark when projected against the solar disk) that are cool magnetic structures and not part of the corona (see, e.g., Scholl and Habbal, 2008; Krista and Gallagher, 2009). Coronal hole magnetic fields are known to be more uniform and unipolar than in other regions (see below). The boundaries between coronal holes and surrounding regions are sometimes sharp, sometimes diffuse, and sometimes filled with many small loops (Hudson, 2002).

Coronal holes are more or less indistinguishable from their surroundings in the photosphere and low chromosphere, and usually one cannot see any significant intensity contrast between hole and non-hole regions until the temperature exceeds about 105 K. Spectra, however, can help make the distinction clearer. Teplitskaya et al. (2007) found that central self-reversals in the chromospheric Ca ii H and K lines are noticeably different in coronal holes as opposed to surrounding quiet-Sun regions. A frequently used observational diagnostic of coronal hole boundaries is the He i 10830 Å near-infrared absorption line triplet (Harvey et al., 1975; Harvey and Recely, 2002). At these wavelengths, the absorption is weakest in coronal holes (i.e., the intensity is highest) and spectroheliogram images show the coronal holes quite clearly. It is somewhat counterintuitive that a spectral line of a neutral species (He0) should be sensitive to the properties of the hot corona. However, the atomic level populations that determine the He i 10830 Å source function are unusually responsive to photoionization from UV wavelengths shortward of 504 Å. The overlying solar corona emits these wavelengths in abundance. In coronal hole regions, though, the corona generally has a lower density and temperature, and thus there is less intense UV and X-ray emission to populate the upper levels of the He0 triplet state (see, e.g., Zirin, 1975; Andretta and Jones, 1997; Centeno et al., 2008). This gives rise to reduced absorption. The He i 10830 Å lines are also good probes of supersonic outflow velocities in distant stellar winds (see, e.g., Dupree et al., 2005; Kwan et al., 2007; Sanz-Forcada and Dupree, 2008).

Another observational diagnostic of coronal holes is their elemental abundance signature (e.g., Feldman, 1998; Feldman and Widing, 2003). In the upper chromosphere, transition region, and low corona, holes exhibit abundances very close to those measured in the photosphere. This stands in contrast to other regions (quiet Sun and active regions), which show significant enhancements in the abundances of elements with low first ionization potential (FIP). This selective fractionation is believed to occur in the upper chromosphere, where low-FIP elements become ionized and high-FIP elements remain more neutral. These patterns extend into the heliosphere, where high-speed flows associated with coronal holes are often identifiable from their near-photospheric FIP abundances (von Steiger et al., 1995; Zurbuchen et al., 2002). However, there is still no widespread agreement about the exact physical processes that give rise to this preferential ionization.

The number, sizes, and heliographic locations of coronal holes vary as a function of the solar activity cycle. Large polar holes exist for about 7 years around solar minimum, and are not present for about 3 or 4 years around solar maximum. However, in the declining phase of activity soon after the maximum, it is possible to see the gradual growth of the new-polarity polar coronal holes. This occurs as a number of smaller high-latitude holes eventually collect together at the poles (Timothy et al., 1975; Harvey and Recely, 2002). Taking this growth phase into account, there are only about 1 or 2 years at solar maximum without any distinct high-latitude coronal hole presence. Figure 3 illustrates the growth phase around the peak of solar cycle 23 in 2001. The growth and full “reappearance” of polar coronal holes at this time was described by Miralles et al. (2001a) and McComas et al. (2002). The post-maximum growth of new polar coronal holes lasts about twice as long as their disappearance in the rising phase of the next maximum (Waldmeier, 1981; Fisher and Sime, 1984).

Polar view of the development of the north polar coronal hole from January to August 2001 (e.g., Carrington rotations 1972 to 1979), using reconstructed coronal hole boundaries from Kitt Peak He i 10830 Å maps. The maximum of solar activity occurred between late 2000 and early 2001. Data from the National Solar Observatory/Kitt Peak were produced cooperatively by NSF/NOAO, NASA/GSFC, and NOAA/SEL.

Many low-latitude coronal holes tend to be situated near the edges of magnetically complex active regions. Sometimes active regions emerge within the coronal holes themselves; these have been called “sea anemone” type regions from their spiky, flower-like appearance (Shibata et al., 1994; Asai et al., 2008). Evolving magnetic interactions between active regions and coronal holes have been studied both as a means of enhancing the mass flux of the associated solar wind on nearby open flux tubes (e.g., Habbal et al., 2008; Wang et al., 2009) and as a possible explanation for the nearly rigid rotation of coronal holes (Wang et al., 1996; Antiochos et al., 2007). A burst of emerging magnetic flux in one of these active regions may give rise to new systems of loop connections in the area bordering the coronal hole, and thus cause the coronal hole to decrease in size. This kind of rapid topological evolution of the magnetic field may be relevant in explaining extreme space weather events such as “the day the solar wind disappeared” (i.e., the dramatic drop in the in situ density seen on 11 May 1999; see Janardhan et al., 2008).

Photospheric magnetograms show that coronal holes are more unipolar than other regions; i.e., they have a larger degree of magnetic flux imbalance between the two polarities (Levine, 1982; Wang, 2009). For the large polar coronal holes, this appears to be the long-term outcome of the decay of active-region magnetic fields and their eventual diffusion up to the poles. The unipolar nature of coronal holes is likely to be related to their connection with open-field solar wind streams. As described in Section 2, one reason why coronal holes are dark is that the solar wind carries away both mass and energy, leaving a lower density and pressure. In addition, Abramenko et al. (2006a) and Hagenaar et al. (2008) found that the local rate of emergence of small-scale magnetic flux (mostly in the form of “ephemeral” small-scale bipoles) is substantially lower in unipolar regions than in more mixed or balanced regions of positive and negative magnetic polarity. In most theories of coronal heating of closed loops, the total flux and the overall complexity of the field both drive the total heating rate. Thus, the lower emergence rate of new flux elements in coronal holes may be another factor determining why they have lower densities and pressures (i.e., less coronal heating; see, e.g., Rosner et al., 1978) and thus why they are dark.

Over the past few decades, the magnetic connection between coronal holes and the fast solar wind has been traced down to ever smaller spatial scales. We now can say with some certainty that much of the plasma that eventually becomes the time-steady solar wind seems to originate in thin magnetic flux tubes (with observed sizes of order 50–200 km) observed mainly in the dark lanes between the ∼ 1000 km size photospheric granulation cells. These strong-field (1–2 kG) flux tubes have been called G-band bright points and network bright points, and groups of them have been sometimes termed “solar filigree” (e.g., Dunn and Zirker, 1973; Spruit, 1984; Berger and Title, 2001; Tsuneta et al., 2008). These flux tubes are concentrated most densely in the supergranular network (i.e., the bright lanes between the larger ∼ 30,000 km size supergranulation cells). Somewhere in the low chromosphere, the thin flux tubes expand laterally to the point where they merge with one another into a more-or-less homogeneous network field distribution of order ∼ 100 G. This merged (mainly vertically oriented) field is associated mainly with the lanes and vertices between supergranular cells. Because this field does not fill the entire coronal volume, it is still susceptible to an additional stage of lateral expansion and weakening. Thus, at a larger height in the chromosphere, these network flux bundles are believed to undergo further broadening into so-called “funnels” (Gabriel, 1976; Dowdy et al., 1986). However, it is still unclear to what extent the closed fields in the supergranular cell centers affect the canopy-like regions between funnels (e.g., Schrijver and Title, 2003). Figure 4 illustrates the successive merging of unipolar field in coronal holes.

Summary of the largely unipolar magnetic field structure of polar coronal holes, with the fields of view successively widening from flux tubes in intergranular lanes (a), to a “funnel” rooted in a supergranular network lane (b), and finally to the extended corona (c). Adapted from Figure 1 of Cranmer and van Ballegooijen (2005).

Observations of blueward Doppler shifts in supergranular network lanes and vertices, especially in large coronal holes, may be evidence for either the “launching” of the solar wind itself or for upward-going waves that are linked to wind acceleration processes (e.g., Hassler et al., 1999; Peter and Judge, 1999; Aiouaz et al., 2005; Tu et al., 2005). These measurements are consistent with several models of the dynamic, multi-species solar wind in superradially expanding funnels (Byhring et al., 2008; Marsch et al., 2008). However, this interpretation of the data is still not definitive, because there are other observational diagnostics that have shown more of a blueshift in the supergranular cell-centers between funnels (e.g., He i 10830 Å; Dupree et al., 1996; Malanushenko and Jones, 2004). There may be subtle radiative transfer effects that preferentially brighten regions of upflow or downflow (see, e.g., Chae et al., 1997; Avrett, 1999), and these may need to be taken into account in order to understand the meaning of the measured Doppler shifts in these regions.

Lastly, it is important to mention the phenomenon of transient coronal holes (sometimes known as “coronal dimmings”). These are rapid reductions in the UV and X-ray intensity in discrete patches that appear to be spatially and temporally correlated with the liftoff of CME plasma (e.g., Rust, 1983; Thompson et al., 2000; Yang et al., 2008). Spectroscopically, these regions are seen to exhibit similar characteristics as normal coronal holes, including Doppler blueshifts (Harra et al., 2007) and large amplitudes of nonthermal wave broadening (McIntosh, 2009). UV coronal dimmings are beginning to be used as diagnostics for the amount of plasma released — i.e., the total mass — in the CME event (e.g., Aschwanden et al., 2009). It should be noted that transient coronal holes represent just one kind of observed dimming that is associated with time-dependent flare/CME activity; there are other types of dimmings that do not resemble coronal holes (Hudson, 2002).

4 Properties of Off-Limb Coronal Holes

Coronal holes observed above the solar limb usually trace out the same regions that are identified as dark coronal-hole “patches” directly on the solar disk. Thus, the lower plasma density that more or less defines the off-limb coronal hole is directly related to the lower density measured on the disk. Section 4.1 briefly discusses how these regions are believed to be connected magnetically with the broader heliosphere. The observations of off-limb coronal holes made with visible-light imaging and polarimetry (Section 4.2) and ultraviolet spectroscopy (Section 4.3) are also summarized below.

4.1 Magnetic connectivity with the solar wind

Although the magnetic field in the solar corona is generally too weak to be measured directly, the overall morphology of the field lines can be extrapolated from magnetograms taken at the level of the photosphere. One popular technique is the “potential field source surface” (PFSS) method, which assumes the corona is current-free out to a spherical surface (set typically at a radius between 2.5 and 3.5 solar radii, or R⊙), above which the field is radial (e.g., Schatten et al., 1969; Altschuler and Newkirk Jr, 1969; Hoeksema and Scherrer, 1986). The PFSS method has been shown to create a relatively good mapping between the Sun and the heliosphere (Arge and Pizzo, 2000; Luhmann et al., 2002; Wang and Sheeley Jr, 2006; Wang, 2009), although the results can be problematic for regions dominated by stream-stream interactions (Poduval and Zhao, 2004).

By far, the strongest causal link between a specific type of coronal structure (measured via remote sensing) and a particular type of quasi-steady solar wind flow (measured in situ) is the connection between large coronal holes and high-speed streams (Wilcox, 1968; Krieger et al., 1973). The general interpretation of this correlation — together with the results of magnetic extrapolation models such as PFSS — is that coronal holes represent a bundle of open flux tubes that flare out horizontally as distance increases. In other words, the coronal hole flux tubes expand superra-dially. Although there are some observations that appear to support other interpretations (Woo et al., 1999; Habbal et al., 2001; Woo, 2005; Woo and Druckmüllerová, 2008), the preponderance of evidence seems clearly to support the idea that fast solar wind streams emerge mainly from superradially expanding coronal holes (e.g., Guhathakurta et al., 1999b; Cranmer et al., 1999b; Jones, 2005; Wang and Sheeley Jr, 2006; Wang et al., 2007).

In contrast to the rather definitive correlation between large coronal holes and the fast solar wind, the coronal sources of the more chaotic slow-speed solar wind are not as well understood (see Schwenn, 2006). Two regions that are frequently cited as sources of slow wind are: (1) boundaries between coronal holes and streamers, and (2) narrow plasma sheets that extend out from the tops of streamer cusps (Wang et al., 2000; Strachan et al., 2002; Susino et al., 2008). These regions tend to dominate around solar minimum. Note that the former type of boundary region tends to contain flux tubes that may be classified as coronal holes when using the theoretical definition (i.e., footpoints of field lines that are open; see Section 1) but would not be defined as such when using the observational definitions (i.e., low emission or low density).

During more active phases of the solar cycle, there is evidence that slow solar wind streams also emanate from small coronal holes (e.g., Nolte et al., 1976; Neugebauer et al., 1998; Zhang et al., 2003) and active regions (Hick et al., 1995; Liewer et al., 2004; Sakao et al., 2007). During the rising phase of solar activity, there seems to be a relatively abrupt (< 6 month) change in the locations of slow wind footpoints: from the high-latitude hole/streamer boundaries to the low-latitude active region and small coronal hole regions (Luhmann et al., 2002). The ability of many of these kinds of regions to produce slow wind was modeled by Cranmer et al. (2007) and Wang et al. (2009); see also Section 5.

4.2 Visible light observations

Measurements of the plasma properties in the extended corona (i.e., r ≈ 1.5 to 10 R⊙, where the main solar wind acceleration occurs) require the bright solar disk to be occulted. The coronal emission is many orders of magnitude less bright than the emission from the solar disk, so even the vast majority of “stray light” that diffracts around the occulting edge must be eliminated. Visible-light coronagraphs that combine stray-light rejection with linear polarimetry have the ability to measure the Thomson-scattered polarization brightness (pB) in the corona. The use of pB rather than the total coronal brightness eliminates the contribution from the dust-scattered F-corona, which is believed to be unpolarized up to distances of about 5 R⊙. Because the coronal plasma is optically thin to the Thomson-scattered photons, pB is proportional to the line-of-sight integral of the electron density ne, multiplied by a known scattering function. Methods for inverting this integral to derive ne as a function of position in various coronal structures have been developed and improved over the years (e.g., van de Hulst, 1950; Altschuler and Perry, 1972; Munro and Jackson, 1977; Guhathakurta and Holzer, 1994; Frazin et al., 2007). For coronal holes, the LASCO (Large Angle and Spectrometric Coronagraph) instrument on SOHO has also been used to probe the superradial expansion of open magnetic flux tubes (DeForest et al., 1997, 2001) and the evolution of transient polar jets (Wang et al., 1998; Wood et al., 1999). The White Light Coronagraphs on Spartan 201 (Fisher and Guhathakurta, 1995) and on the UVCS (Ultraviolet Coronagraph Spectrometer) instrument aboard SOHO (e.g., Kohl et al., 1995; Romoli et al., 2002) have provided electron densities between 1.5 and 5 R⊙ in coronal holes.

Figure 5 illustrates a selection of visible-light measurements of the electron density in coronal holes and compares them to similar measurements of streamers and to a semi-empirical model of the chromosphere, transition region, and low corona (Avrett and Loeser, 2008). The blue coronal hole curves were adapted from the results of Fisher and Guhathakurta (1995) (dotted), Cranmer et al. (1999b) (solid), Doyle et al. (1999) (dashed), and Guhathakurta et al. (1999a) (dot-dashed). The red curves for equatorial helmet streamers were adapted from the results of Sittler Jr and Guhathakurta (1999) (solid) and Gibson et al. (1999) (dashed).

Comparison of empirically determined densities in the upper solar atmosphere. Avrett and Loeser (2008) values of electron number density (solid black curve) and total hydrogen number density (dot-dashed black curve) are compared with various visible-light pB electron number densities for coronal holes (blue curves) and streamers (red curves); see text for details.

Note that streamers are denser than coronal holes by about a factor of 10, but the hole measurements themselves can often exhibit variations in the electron density by factors of the order of 2–3. Much of this spread is likely to be the result of different lines of sight passing through regions that contain varying numbers of polar plumes (see, e.g., Cranmer et al., 1999b, 2008). Some of the cited pB observations were optimized to avoid bright concentrations of plumes, and others have been purposefully averaged over the full range of coronal hole substructure. It is also possible that absolute calibration uncertainties may still exist between the different instruments used to determine pB and ne, and this could compound the reported range of variation in coronal hole electron densities.

For a steady-state solar wind outflow, the conservation of mass demands that the product of density, flow speed, and cross-sectional area of the flux tube remain constant. Thus, if the magnetic geometry and the electron density are known, mass conservation allows the solar wind outflow speed to be computed. Kohl et al. (2006) used the representative values of ne shown in Figure 5 together with a range of estimates for the superradial flux-tube expansion of coronal holes to determine outflow speeds in coronal holes. Figure Fig41a of Kohl et al. (2006) illustrates the result of this process, which shows a large range of values reflecting the uncertainties in both ne and the flux-tube area factor. Despite these uncertainties, though, the electron densities that became available in the 1990s demonstrated that the fast solar wind accelerates rapidly in coronal holes — probably reaching half of its asymptotic terminal speed (u∞ ≈ 700–800 kms−1) by heights no larger than 2–4 R⊙.

The increased sensitivity of the LASCO instrument over earlier coronagraphs revealed a nearly continual release of low-contrast density inhomogeneities, or “blobs,” from the cusps of helmet streamers (Sheeley Jr et al., 1997; Tappin et al., 1999; Wang et al., 2000; Chen et al., 2009). These features were seen to accelerate up to speeds of order 300–400 km s−1 by the time they reached the outer edge of the LASCO field of view (r ≈ 30 R⊙); see also Figure 8 below. The blobs are typically only about 10% to 15% brighter or dimmer than the surrounding streamer material. Because of this low contrast, these features do not appear to comprise a large fraction of the mass flux of the slow solar wind. However, it is still unclear whether blobs are passive “tracers” that flow with the solar wind speed, or whether they are wavelike fluctuations that propagate relative to the background solar wind reference frame. This diagnostic tool has been much more difficult to apply in coronal holes than it has in the bright streamers, so no firm measurements of the fast wind acceleration yet exist from this technique.

Visible light measurements have also revealed evidence for compressive magnetohydrodynamic (MHD) waves that propagate along open field lines in coronal holes. Intensity oscillations measured by the UVCS and EIT instruments on SOHO were found to have periodicities between about 10 and 30 minutes and are consistent with being upwardly propagating slow-mode magnetosonic waves (DeForest and Gurman, 1998; Ofman et al., 1999, 2000). The relative amplitude of the density fluctuations (δn/n0) for these waves was found to range between about 0.03 and 0.15 (see Cranmer, 2004a). This is consistent with measurements of the density fluctuation amplitudes made at larger distances via radio scintillations (Spangler, 2002) and in situ instruments (Tu and Marsch, 1994). There have also been claims that low-frequency oscillations have been measured in H I Lyα emission (Morgan et al., 2004; Bemporad et al., 2008; Telloni et al., 2009). In these cases, however, it is extremely important to take into account all of the relevant instrumental effects. These measurements still appear to be provisional.

As seen in Section 2 above, coronal holes have long been observed as the sites of thin, ray-like polar plumes. The earliest measurements of polar plume properties were made in broad-band visible light, and these dense strands are often seen to stand out distinctly from the ambient interplume corona. It is not clear, though, to what extent off-limb observations (which integrate over long optically thin lines of sight) ever capture only the “pure” plume or interplume plasmas. Space-based observations from, e.g., Spartan 201 and SOHO improved our ability to measure the physical properties in and between plumes (e.g., Fisher and Guhathakurta, 1995; DeForest et al., 1997; Cranmer et al., 1999b; DeForest et al., 2001). Although the brightest plumes are still discernible at the uppermost heights observed by LASCO (i.e., 30–40 R⊙), the plume/interplume density contrast becomes too low to measure clearly in interplanetary space (r > 60 R⊙). However, indirect and possibly plume-related signatures in the in situ data have been reported by Thieme et al. (1990), Reisenfeld et al. (1999), and Yamauchi et al. (2002). The disappearance of plumes probably is the result of some combination of transverse pressure balance (i.e., dense plumes expanding to fill more of the available volume; see Del Zanna et al., 1998) and MHD instabilities that can mix the two components (Parhi et al., 1999; Andries and Goossens, 2001).

4.3 Ultraviolet spectroscopy

Ultraviolet spectroscopy of the corona is a powerful tool for obtaining detailed empirical descriptions of solar plasma conditions (see, e.g., Kohl and Withbroe, 1982; Withbroe et al., 1982). Coronal holes, being the lowest density regions of the outer solar atmosphere, exhibit a complex array of plasma parameters due to their nearly collisionless nature. As a result, every ion species tends to have its own unique temperature, its own type of departure from a Maxwellian velocity distribution, and its own outflow speed. After a brief summary of near-limb measurements made with the SUMER instrument on SOHO, this section mainly describes results at larger heights (in the more clearly collisionless extended corona) from UVCS.

The un-occulted SUMER (Solar Ultraviolet Measurements of Emitted Radiation) spectrometer has observed off-limb regions up to heights of approximately 1.3 R⊙ in coronal holes (Wilhelm et al., 1995, 2000, 2004, 2007). In polar regions at solar minimum, ion temperatures exceed electron temperatures even at r ∼ 1.05 R⊙, where densities were presumed to be so high as to ensure rapid collisional coupling and thus equal temperatures for all species (Seely et al., 1997; Tu et al., 1998; Landi and Cranmer, 2009). Spectroscopic evidence is also mounting for the presence of transverse Alfvén waves propagating into the corona (Banerjee et al., 1998, 2009; Dolla and Solomon, 2008; Landi and Cranmer, 2009).

Electron temperatures derived from line ratios (Habbal et al., 1993; David et al., 1998; Doschek et al., 2001; Wilhelm, 2006; Landi, 2008) exhibit relatively low values in the off-limb coronal holes (Te ∼ 800, 000 K) that are not in agreement with higher temperatures derived from “frozen-in” in situ charge states (Ko et al., 1997). It is difficult to reconcile these observations with one another in the absence of either non-Maxwellian electron velocity distributions or strong differential flows between different ion species near the Sun (Esser and Edgar, 2000). However, some models consistent with both the SUMER temperatures and the in situ charge states are being produced (e.g., Laming and Lepri, 2007).

Figure 6 displays a range of temperatures measured in coronal holes and high-speed wind streams, and it shows how the SUMER electron temperatures (Te) are noticeably lower than the heavy ion temperatures (e.g., shown for the O+5 ions that correspond to the bright O VI 1032, 1037 Å spectral lines) even in the low corona. The degree of agreement between the spectroscopic measurements and one-fluid models of the low corona (i.e., the semi-empirical model of Avrett and Loeser (2008) and the theoretical model of Cranmer et al. (2007)) depends on the height of the sharp transition region between chromospheric (104 K) and coronal (106 K) temperatures.

Radial dependence of empirical and model temperatures in polar coronal holes and fast wind streams. Mean plasma temperatures from a semi-empirical model (dashed black curve; Avrett and Loeser, 2008) and from a turbulence-driven coronal heating model (solid black curve; Cranmer et al., 2007). Te from off-limb SUMER measurements made by Wilhelm (2006) (dark blue bars) and Landi (2008) (light blue bars), Tp from UVCS measurements assembled by Cranmer (2004b) (see text), and perpendicular O+5 ion temperatures from Landi and Cranmer (2009) (open green circles) and Cranmer et al. (2008) (filled green circles). In situ proton and electron temperatures in the fast wind (r > 60 R⊙) are from Cranmer et al. (2009).

The UVCS instrument on SOHO is a combination of an ultraviolet spectrometer and a linearly occulted coronagraph that observes a 2.5 R⊙ long swath of the extended corona, oriented tangentially to the radial direction at heliocentric distances ranging between about 1.5 and 10 R⊙ (Kohl et al., 1995, 1997, 1998, 2006). In coronal holes, UVCS measurements have allowed many key details about the velocity distributions of H0, O+5, and Mg+9 to be derived. For the resonantly scattered emission lines seen at large heights with UVCS, the most straightforward plasma diagnostic is to use the Doppler-broadened line width as a sensitive probe of the overall variance of random particle motions along the line of sight. In other words, measuring the line width provides a constraint on the so-called “kinetic temperature” (i.e., a combination of microscopic stochastic motions and macroscopic [but unresolved] motions due to waves or turbulence) along the direction perpendicular to the (nearly radial) magnetic field lines.

In the ionized solar corona, a given hydrogen nucleus spends most of its time as a free proton, and only a small fraction of time as a bound H0 atom. Thus, the measured plasma properties of neutral hydrogen are considered to be valid proxies of the proton properties below about 3 R⊙ (Allen et al., 2000). Spartan 201 and UVCS observations of the H I Lyα emission line in coronal holes indicated rather large proton kinetic temperatures in the direction perpendicular to the magnetic field (Tp⊥ ∼ 3 MK) and also the possibility of a mild temperature anisotropy (with Tp⊥ > Tp∥) above heights of 2–3R⊙ (Kohl et al., 1997; Cranmer et al., 1999b; Antonucci et al., 2004; Kohl et al., 2006).

UVCS observations indicated that the O+5 ions are much more strongly heated than protons in coronal holes, with perpendicular temperatures in excess of 200 MK (see Figure 7). This exceeds the temperature at the central core of the Sun by an order of magnitude! The UVCS measurements also provided signatures of temperature anisotropies possibly greater than T⊥i/T∥i ≈ 10 (e.g., Cranmer et al., 1999b, 2008). The measured kinetic temperatures of O+5 and Mg+9 are significantly greater than mass-proportional when compared with protons, with Ti/Tp > mi/mp (see also Kohl et al., 1999, 2006). The surprisingly “extreme” properties of heavy ions in coronal holes have led theorists to develop a number of new ideas regarding the heating and acceleration of the solar wind; these are discussed further in Section 5.4.

Combined image of the solar corona from 17 August 1996, showing the solar disk in Fe XII 195 Å intensity from EIT (yellow inner image) and the extended corona in O VI 1032 Å intensity from UVCS (red outer image). Axisymmetric field lines are from the solar-minimum model of Banaszkiewicz et al. (1998), and O VI emission line profiles (bottom) are from SUMER (Warren et al., 1997, left) and UVCS (Kohl et al., 1997, right).

Figure 6 shows UVCS perpendicular temperatures for protons and O+5 ions in coronal holes. The O+5 data points were taken from the recent re-analysis of solar minimum data from 1996–1997 by Cranmer et al. (2008). The proton temperature data were assembled by Cranmer (2004b) from a number of individual measurements of the H I Lyα profile at solar minimum. The sources of these measurements are: Cranmer et al. (1999b) (squares), Esser et al. (1999) (diamonds), Zangrilli et al. (1999) (asterisks), and Antonucci et al. (2000) (triangles). The kinetic proton temperatures are of order 2–3.5 MK, but in Figure 6 we attempted to remove the contribution of nonthermal wave broadening. The semi-empirical model of Cranmer and van Ballegooijen (2005) was used to specify the amplitude of transverse Alfvén waves as a function of height, and their contribution to the line widths was subtracted. The remaining “microscopic” T⊥p does not show as clear a signal of “preferential” proton heating as would be apparent from the larger kinetic temperature. Although one can still marginally see that Tp > Te, the existing measurements of Tp and Te do not fully overlap with one another in radius. Improved measurements are needed in order to better constrain the proton and electron heating rates in the corona.

The UVCS emission line data contain information about the Doppler motions of atoms and ions along the magnetic field (i.e., transverse to the line of sight). The so-called “Doppler dimming” diagnostic technique provides constraints on both the bulk outflow speed along the field and the parallel kinetic temperature (for more details, see Kohl and Withbroe, 1982; Noci et al., 1987; Kohl et al., 2006). In coronal holes, Doppler-dimmed line intensities from UVCS are consistent with the outflow velocity for O+5 being larger than the outflow velocity for protons by as much as a factor of two at large heights (Kohl et al., 1998; Li et al., 1998; Cranmer et al., 1999b). Figure 8 illustrates the outflow speeds measured by UVCS in coronal holes, and compares with the theoretical model of the fast solar wind presented by Cranmer et al. (2007). Also shown for comparison are observational and theoretical data for the slow solar wind associated with equatorial helmet streamers at solar minimum.

Radial dependence of solar wind outflow speeds. UVCS Doppler dimming determinations for protons (red; Kohl et al., 2006) and O+5 ions (green; Cranmer et al., 2008) are shown for polar coronal holes, and are compared with theoretical models of the polar and equatorial solar wind at solar minimum (black curves; Cranmer et al., 2007) and the speeds of “blobs” measured by LASCO above equatorial streamers (open circles; Sheeley Jr et al., 1997).

In contrast to many prior analyses of UVCS data, which concluded that there must be both intense preferential heating of the O+5 ions and a strong field-aligned anisotropy, Raouafi and Solanki (2004), Raouafi and Solanki (2006), and Raouafi et al. (2007) reported that there may not be a compelling need for O+5 anisotropy depending on the assumptions made about the other plasma properties of the coronal hole (e.g., electron density). However, Cranmer et al. (2008) performed a detailed re-analysis of these observations and concluded that there remains strong evidence in favor of both preferential O+5 heating and acceleration and significant O+5 ion anisotropy (in the sense T⊥i > T∥i) above r ≈ 2.1 R⊙ in coronal holes. In determining these properties, it was found to be important to search the full range of possible ion temperatures and flow speeds, and not to make arbitrary assumptions about any given subset of the parameters.

The UVCS results discussed above are similar in character to in situ measurements made in the fast solar wind, but they imply more extreme departures from thermodynamic equilibrium in the extended corona. For example, proton velocity distributions measured in the fast solar wind between 0.3 and 1 AU have anisotropic cores with Tp⊥ > Tp∥, and their magnetic moments increase with increasing distance; this implies net input of perpendicular energy on kinetic scales (e.g., Marsch et al., 1982; Marsch, 2006). Many heavy ions appear to flow faster than the protons by about the local Alfvén speed (Hefti et al., 1998; Reisenfeld et al., 2001), and in the fastest solar wind streams they are also heated preferentially in the same sense as in the corona (Collier et al., 1996).

In the years since the solar minimum of 1996–1997, UVCS observed a large number of other coronal holes that appeared throughout the maximum of solar cycle 23 and the new-millennium solar minimum of 2007–2009. UVCS tends to observe only the largest coronal holes, since when the smallest holes rotate to the solar limb their UV line profiles tend to be contaminated by emission from streamers in the foreground and background. This selection effect naturally screens out small coronal holes that have been correlated with slow solar wind streams at 1 AU (Nolte et al., 1976; Neugebauer et al., 1998). In the cases where UVCS and in situ measurements were made for the same regions associated with large coronal holes, high speeds in excess of 600 km s−1 were inevitably seen in interplanetary space (Miralles et al., 2004, 2006). However, the O+5 outflow speeds measured in the extended corona via Doppler dimming have showed a substantial range of variation. For example, Miralles et al. (2001b) found that the outflow speeds at 2–3 R⊙ in an equatorial coronal hole were approximately three times lower than those measured in the polar coronal holes from 1996–1997 at similar heights (see also Poletto et al., 2002). This implies that the range of coronal heights over which the acceleration of the solar wind occurs can vary greatly, even when the wind at 1 AU ends up similarly fast.

UVCS also has measured the plasma properties in bright polar plumes. The densest concentrations of polar plumes along the line of sight are seen to exhibit narrower line widths — i.e., lower kinetic temperatures — than the lower-density interplume regions (Kohl et al., 1997; Noci et al., 1997; Kohl et al., 2006). Similarly, plumes are seen to have lower outflow speeds than the interplume regions (Giordano et al., 2000; Teriaca et al., 2003; Raouafi et al., 2007), although at low heights the data are not as clear-cut (e.g., Gabriel et al., 2003). UVCS also has put constraints on the plume/interplume density contrast and the filling factor of polar plumes in coronal holes. Cranmer et al. (1999b) used a large number of UVCS synoptic measurements to determine statistically that, at heights around r ≈ 2 R⊙, the plume/interplume density ratio is approximately 2, and polar coronal holes are comprised of about 25% plume and 75% interplume plasma (corresponding to ∼ 40 individual plumes distributed throughout the coronal hole). Earlier measurements made closer to the limb showed a higher density contrast and a smaller filling factor, so the UVCS data are generally consistent with lateral expansion of polar plumes with increasing distance.

It is still relatively unknown how much of the mass, momentum, and energy flux of the fast solar wind comes from polar plumes. Despite that uncertainty, though, there have been several reasonably successful models of polar plume formation. Wang (1994, 1998) presented models of polar plumes as the extensions of flux tubes with concentrated bursts of added coronal heating at the base — presumably via nanoflare-like reconnection events in X-ray bright points (see also DeForest et al., 2001). In these models, the extra basal heat input is balanced by conductive losses to produce the larger plume density. The heating rate in the extended corona is not affected by the basal burst, but the larger density in the flux tube gives rise to less heating per particle at all heights, which leads to lower temperatures in the extended corona and a smaller gas pressure force for solar wind acceleration. This model is consistent with the smaller temperatures and outflow speeds measured in plumes with UV spectroscopy.

UVCS made the first spectroscopic measurements of polar jets in coronal holes (Dobrzycka et al., 2000, 2006). The events observed by EIT, LASCO, and UVCS during the 1996–1997 solar minimum tended to be “cool jets” with higher densities, lower temperatures, and faster outflows than the surrounding coronal holes (see also Wang et al., 1998). More recently, Hinode has observed a new population of “hot” X-ray jets in coronal holes (Culhane et al., 2007; Cirtain et al., 2007; Shimojo et al., 2007; Filippov et al., 2009). UVCS found that some of these events persist up to heights of at least 1.7 R⊙ and that the jet protons remain hotter than the surrounding coronal hole (Miralles et al., 2007). Thus, there appear to exist two distinct kinds of polar jets (cool and hot), with differences possibly related to the relative degrees of heating and adiabatic expansion of the jet parcels. Jets and plumes have roughly similar angular sizes and intensity contrasts near the solar limb, and there is growing evidence that they share a common origin (e.g., Raouafi et al., 2008). It is possible that the only substantial difference between the two phenomena is the duration of the bursts of basal heating; i.e., jets seem to be the result of short-lived bursts of heating, whereas plumes may be the product of base-heating events that last longer than several hours.

5 Coronal Heating and Solar Wind Acceleration

Despite more than a half-century of study, the basic physical processes that are responsible for heating the million-degree corona and accelerating the supersonic solar wind are not known. This section broadens the topic of this paper a bit beyond just coronal holes, since an understanding of solar wind acceleration naturally encompasses not only the question of why fast solar wind streams are fast, but also why (various kinds of) slow solar wind streams are slow. Section 5.1 summarizes some of the major issues regarding coronal energy deposition. The next two subsections describe two alternate views of solar wind acceleration via waves and turbulence in open flux tubes (Section 5.2) and reconnection between open and closed flux tubes (Section 5.3). Lastly, Section 5.4 reviews how collisionless kinetic effects in coronal holes (i.e., preferential ion heating and temperature anisotropies) can be used to more conclusively identify the detailed physical processes that produce the solar wind.

5.1 Sources of energy

Different physical mechanisms for heating the corona probably govern active regions, closed loops in the quiet corona, and the open field lines that give rise to the solar wind (see other reviews by Marsch, 1999; Hollweg and Isenberg, 2002; Longcope, 2004; Gudiksen, 2005; Aschwanden, 2006; Klimchuk, 2006). The ultimate source of the energy is the solar convection zone (e.g., Abramenko et al., 2006b; McIntosh et al., 2007). A key aspect of solving the “coronal heating problem” is thus to determine how a small fraction of that mechanical energy is transformed into magnetic free energy and thermal energy above the photosphere. It seems increasingly clear that loops in the low corona are heated by small-scale, intermittent magnetic reconnection that is driven by the continual stressing of their magnetic footpoints. However, the extent to which this kind of impulsive energy addition influences the acceleration of the solar wind is not yet known.

Intertwined with the coronal heating problem is the heliophysical goal of being able to make accurate predictions of how both fast and slow solar wind streams are accelerated. Empirical correlation techniques have become more sophisticated and predictively powerful (e.g., Wang and Sheeley Jr, 1990, 2006; Arge and Pizzo, 2000; Leamon and McIntosh, 2007; Cohen et al., 2007; Vršnak et al., 2007) but they are limited because they do not identify or utilize the physical processes actually responsible for solar wind acceleration. There seem to be two broad classes of physics-based models that attempt to self-consistently answer the question: “How are fast and slow wind streams heated and accelerated?”

-

1.

In wave/turbulence-driven (WTD) models, it is generally assumed that the convection-driven jostling of magnetic flux tubes in the photosphere drives wave-like fluctuations that propagate up into the extended corona. These waves (usually Alfvén waves) are often proposed to partially reflect back down toward the Sun, develop into strong MHD turbulence, and dissipate over a range of heights. These models also tend to explain the differences between fast and slow solar wind not by any major differences in the lower boundary conditions, but instead as an outcome of different rates of lateral flux-tube expansion over several solar radii as the wind accelerates (see, e.g., Hollweg, 1986; Wang and Sheeley Jr, 1991; Matthaeus et al., 1999; Cranmer, 2005; Suzuki, 2006; Suzuki and Inutsuka, 2006; Cranmer et al., 2007; Verdini and Velli, 2007; Verdini et al., 2009).

-

2.

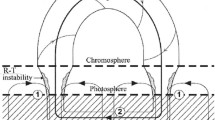

In reconnection/loop-opening (RLO) models, the flux tubes feeding the solar wind are assumed to be influenced by impulsive bursts of mass, momentum, and energy addition in the lower atmosphere. This energy is usually assumed to come from magnetic reconnection between closed, loop-like magnetic flux systems (that are in the process of emerging, fragmenting, and being otherwise jostled by convection) and the open flux tubes that connect to the solar wind. These models tend to explain the differences between fast and slow solar wind as a result of qualitatively different rates of flux emergence, reconnection, and coronal heating at the basal footpoints of different regions on the Sun (see, e.g., Axford and McKenzie, 1992, 1997; Fisk et al., 1999; Ryutova et al., 2001; Markovskii and Hollweg, 2002, 2004; Fisk, 2003; Schwadron and McComas, 2003; Woo et al., 2004; Fisk and Zurbuchen, 2006).

It is notable that both the WTD and RLO models have recently passed some basic “tests” of comparison with observations. Both kinds of model have been shown to be able to produce fast (υ > 600 km/s), low-density wind from coronal holes and slow (υ < 400 km/s), high-density wind from streamers rooted in quiet regions. Both kinds of model also seem able to reproduce the observed in situ trends of how frozen-in charge states and the FIP effect vary between fast and slow wind streams.

The fact that both sets of ideas described above seem to mutually succeed at explaining the fast/slow solar wind could imply that a combination of both ideas would work best. However, it may also imply that the existing models do not yet contain the full range of physical processes — and that once these are included, one or the other may perform noticeably better than the other. It also may imply that the comparisons with observations have not yet been comprehensive enough to allow the true differences between the WTD and RLO ideas to be revealed.

Several recent observations have pointed to the importance of understanding the relationships and distinctions between the WTD and RLO models. The impulsive polar jets discussed in Section 4 may be evidence that that magnetic reconnection drives some fraction of the fast solar wind (see also Fisk, 2005; Moreno-Insertis et al., 2008; Pariat et al., 2009). Also, direct observations of Alfvén waves above the solar limb indicate the highly intermittent nature of how kinetic energy is distributed in spicules, loops, and the open-field corona (De Pontieu et al., 2007; Tomczyk et al., 2007; Tomczyk and McIntosh, 2009). Spectroscopic observations of blueshifts in the chromospheric network have long been interpreted as the launching points of solar wind streams, but it remains unclear how nanoflare-like events or loop-openings contribute to the interpretation of these diagnostics (He et al., 2007; Aschwanden et al., 2007; McIntosh et al., 2007). Even out in the in situ solar wind — far above the roiling “furnace” of flux emergence at the Sun — there remains evidence for ongoing reconnection (Gosling et al., 2005; Gosling and Szabo, 2008). There is also evidence that the dominant range of turbulence timescales measured in interplanetary space (i.e., tens of minutes to hours) is related to the timescale of flux cancellation in the low corona (Hollweg, 1990, 2006).

Determining whether the WTD or RLO paradigm — or some combination of the two — is the dominant cause of global solar wind variability is a key prerequisite to building physically realistic predictive models of the heliosphere. Many of the widely-applied global modeling codes (e.g., Riley et al., 2001; Roussev et al., 2003; Tóth et al., 2005; Usmanov and Goldstein, 2006; Feng et al., 2007) continue to utilize relatively simple empirical prescriptions for coronal heating in the energy conservation equation. Improving the identification and characterization of the key physical processes will provide a clear pathway for inserting more physically realistic coronal heating “modules” into three-dimensional MHD codes.

5.2 The Wave/Turbulence-Driven (WTD) solar wind idea

There has been substantial work over the past few decades devoted to exploring the idea that the plasma heating and wind acceleration along open flux tubes may be explained as a result of wave damping and turbulent cascade. No matter the relative importance of reconnections and loop-openings in the low corona, we do know that waves and turbulent motions are present everywhere from the photosphere to the heliosphere, and it is important to determine how they affect the mean state of the plasma. A review of the observational evidence for waves and turbulence in the solar wind is beyond the scope of this paper, but several recent reviews of the remote-sensing and in situ data include Tu and Marsch (1995), Mullan and Yakovlev (1995), Goldstein et al. (1997), Roberts (2000), Bastian (2001), and Cranmer (2002a, 2004a, 2007). Although this subsection mainly describes recent work by the author, these results would not have been possible without earlier work on wave/turbulent heating by, e.g., Coleman (1968), Hollweg (1986), Hollweg and Johnson (1988), Isenberg (1990), Li et al. (1999), Matthaeus et al. (1999), Dmitruk et al. (2001, 2002), and many others.

Cranmer et al. (2007) described a set of models in which the time-steady plasma properties along a one-dimensional magnetic flux tube are determined. These model flux tubes are rooted in the solar photosphere and are extended into interplanetary space. The numerical code developed in that work, called ZEPHYR, solves the one-fluid equations of mass, momentum, and energy conservation simultaneously with transport equations for Alfvénic and acoustic wave energy. ZEPHYR is the first code capable of producing self-consistent solutions for the photosphere, chromosphere, corona, and solar wind that combine: (1) shock heating driven by an empirically guided acoustic wave spectrum, (2) extended heating from Alfvén waves that have been partially reflected, then damped by anisotropic turbulent cascade, and (3) wind acceleration from gradients of gas pressure, acoustic wave pressure, and Alfvén wave pressure.

The only input “free parameters” to ZEPHYR are the photospheric lower boundary conditions for the waves and the radial dependence of the background magnetic field along the flux tube. The majority of heating in these models comes from the turbulent dissipation of partially reflected Alfvén waves (see also Matthaeus et al., 1999; Dmitruk et al., 2002; Verdini and Velli, 2007; Chandran et al., 2009a). Photospheric measurements of the horizontal motions of strong-field intergranular flux concentrations (i.e., G-band bright points) were used to constrain the Alfvén wave power spectrum at the lower boundary. This empirically determined power spectrum is dominated by wave periods of order 5–10 minutes. It is important to note, however, that radio and in situ measurements find that most of the fluctuation power in the solar wind is at lower frequencies (i.e., periods of hours). We still do not yet know (1) if the shape of the power spectrum evolves significantly between the lower solar atmosphere and interplanetary space, or (2) if some low-frequency power is missed by the existing measurements of G-band bright point motions. In any case, as seen below, the resulting wave reflection and turbulent dissipation that comes from just the 5–10 minute periods appear to be sufficient to explain the observed levels of coronal heating and solar wind acceleration.

Non-WKB wave transport equations were solved to determine the degree of linear reflection at heights above the photospheric base (see Cranmer and van Ballegooijen, 2005). The resulting values of the Elsasser amplitudes Z±, which denote the energy contained in upward (Z−) and downward (Z+) propagating waves, were then used to constrain the energy flux in the cascade. Cranmer et al. (2007) used a phenomenological form for the damping rate that has evolved from studies of Reduced MHD and comparisons with numerical simulations. The resulting heating rate (in units of erg s−1 cm−3) is given by

where ρ is the mass density and L⊥ is an effective perpendicular correlation length of the turbulence (see, e.g., Hossain et al., 1995; Zhou and Matthaeus, 1990; Breech et al., 2008; Podesta and Bhattacharjee, 2009; Beresnyak and Lazarian, 2009). Cranmer et al. (2007) used a standard assumption that L⊥ scales with the cross-sectional width of the flux tube (Hollweg, 1986). The term in parentheses above is an efficiency factor that accounts for situations in which the cascade does not have time to develop before the waves or the wind carry away the energy (Dmitruk and Matthaeus, 2003). In open field regions, the cascade is “quenched” when the nonlinear eddy time scale teddy becomes much longer than the macroscopic wave reflection time scale tref. In closed field regions, the correction factor may behave in an opposite sense as it does for open field regions (see, e.g., Gómez et al., 2000; Rappazzo et al., 2008). In most of the solar wind models, though, Cranmer et al. (2007) used n = 1 in Equation (1) based on analytic and numerical results (Dobrowolny et al., 1980; Oughton et al., 2006), but they also tried n = 2 to explore a stronger form of the quenching effect.

Figure 9 summarizes the results of varying the magnetic field properties while keeping the lower boundary conditions fixed. For a single choice for the photospheric wave properties, the models produced a realistic range of slow and fast solar wind conditions. A two-dimensional model of coronal holes and streamers at solar minimum reproduces the latitudinal bifurcation of slow and fast streams seen by Ulysses. An active-region-like enhancement of the magnetic field strength in the low corona generates a high mass flux and a slow wind speed, in agreement with observations of open field lines connected with active regions (see also Wang et al., 2009). As predicted by earlier studies, a larger coronal “expansion factor” naturally gives rise to a slower and denser wind, higher temperature at the coronal base, and lower-amplitude Alfvén waves at 1 AU.

Summary of Cranmer et al. (2007) models: (a) The adopted solar-minimum field geometry of Banaszkiewicz et al. (1998), with radii of wave-modified critical points marked by symbols. (b) Latitudinal dependence of wind speed at ∼ 2 AU for models with n = 1 (multi-color curve) and n = 2 (brown curve), compared with data from the first Ulysses polar pass in 1994–1995 (black curve; Goldstein et al., 1996). (c) T(r) for polar coronal hole (red solid curve), streamer edge (blue dashed curve), and strong-field active region (black dotted curve) models.

In these models, the radial gradient of the Alfvén speed affects where the waves are reflected and damped, and thus whether energy is deposited below or above the Parker (1958a) critical point. Early studies of solar wind energetics (e.g., Leer and Holzer, 1980; Pneuman, 1980; Leer et al., 1982) showed that if there is substantial heating below the critical point, its primary impact is to “puff up” the hydrostatic scale height, drawing more particles into the accelerating wind and thus producing a slower and more massive wind. If most of the heating occurs at or above the critical point, the subsonic atmosphere is relatively unaffected, and the local increase in energy flux has nowhere else to go but into the kinetic energy of the wind (leading to a faster and less dense outflow). The ZEPHYR results shown in Figure 9 display this kind of dichotomy because the superradial expansion creates a much higher critical point over the equatorial regions than over the poles. Additional studies of how and where the mass flux and wind speed are determined include Withbroe (1988), Hansteen and Leer (1995), Hansteen et al. (1997), Janse et al. (2007), and Wang et al. (2009).

Perhaps more surprisingly, varying the coronal expansion factor in the models shown in Figure 9 also produces correlative trends that are in good agreement with in situ measurements of commonly measured ion charge state ratios (e.g., O7+/O6+) and FIP-sensitive abundance ratios (e.g., Fe/O). Cranmer et al. (2007) showed that the slowest solar wind streams — associated with active-region fields at the base — can produce a factor of ∼ 30 larger frozen-in ionization-state ratio of O7+/O6+ than high-speed streams from polar coronal holes, despite the fact that the temperature at 1 AU is lower in slow streams than in fast streams. Furthermore, when elemental fractionation is modeled using a theory based on preferential wave-pressure acceleration (Laming, 2004, 2009; Bryans et al., 2009), the slow wind streams exhibit a substantial relative buildup of elements with low FIP with respect to the high-speed streams. Although the WTD models utilize identical photospheric lower boundary conditions for all of the flux tubes, the self-consistent solutions for the upper chromosphere, transition region, and low corona are qualitatively different. Feedback from larger heights (i.e., from variations in the flux tube expansion rate and the resulting heating rate) extends downward to create these differences.

Another empirical “marker” of heliospheric stream structure is the proton specific entropy, or entropy per proton, which is often approximated as being proportional to \({\rm ln}(T_{p}/n_{p}^{\gamma-1})\), where β ≈ 1.5 is an empirical adiabatic index for solar wind protons (e.g., Burlaga et al., 1990; Pagel et al., 2004). When measured in regions of the (non-CME) heliosphere where corotating interaction regions have not yet formed shocks, this quantity is seen to clearly distinguish slow wind streams from fast wind streams. Figure 10 shows how the specific entropy is positively correlated with wind speed, both in measurements made by the Solar Wind Electron Proton Alpha Monitor (SWEPAM) instrument on ACE (McComas et al., 1998) and in the Cranmer et al. (2007) ZEPHYR models discussed above. Each model data point was computed independently of the others. The models had identical lower boundary conditions at the photosphere, and they differed from one another only by having a different radial dependence of the magnetic field. Because entropy should be conserved in the absence of significant small-scale dissipation, the quantity that is measured at 1 AU may be a long-distance proxy for the near-Sun locations of strong coronal heating. In other words, the comparison of measured and modeled solar wind entropy variations may be a key way to discriminate between competing explanations of solar wind acceleration.

Although Equation (1) describes the plasma heating rate in terms of the local properties of MHD turbulence, it is also possible to see that this expression gives a heating rate proportional to the mean magnetic flux density at the coronal base. As illustrated above in Figure 4, the mean field strength in the low corona is determined by both the photospheric field strength in the intergranular bright points and the total number of bright points that eventually merge their fields together in the low corona. The field strength at this merging height can thus be estimated as B ≈ f*B*, where B* ≈ 1500 G is the (nearly universal) photospheric bright-point field strength and f* is the area filling factor of bright points in the photosphere. The latter quantity appears to vary by more than an order of magnitude in different regions on the Sun, from about 0.002 (at low latitudes at solar minimum) to ∼ 0.1 (in active regions). If the regions below the merging height can be treated using approximations from “thin flux tube theory” (e.g., Spruit, 1981; Cranmer and van Ballegooijen, 2005), then it is possible to express each term in Equation (1) as a function of f* and the photospheric properties. For example, B ∝ ρ1/2 applies to thin flux tubes in pressure equilibrium, and thus ρ at the merging height can be estimated as \(f_{\ast}^{2}\rho_{\ast}\) (where ρ* is the photospheric density). For Alfvén waves at low heights, Z± ∝ ρ−1/4, and so Z± at the merging height scales like \(Z_{\pm\ast}/f_{\ast}^{1/2}\). Also, we assumed that L⊥ ∝ B−1/2. If the quenching factor in parentheses in Equation (1) is neglected, then

Equivalently, Equation (2) implies that Q/Q* ≈ B/B*, and thus that the heating in the low corona scales directly with the mean magnetic field strength there. In a more highly structured field, the latter is equivalent to the magnetic “flux density” averaged over a given region. Observational evidence for such a linear scaling has been found for both a variety of solar regions and other stars as well (see, e.g., Pevtsov et al., 2003; Schwadron et al., 2006; Suzuki, 2006; Kojima et al., 2007; Pinto et al., 2009).

5.3 The Reconnection/Loop-Opening (RLO) solar wind idea

It is clear from observations of the Sun’s highly dynamical “magnetic carpet” (Schrijver et al., 1997; Title and Schrijver, 1998; Hagenaar et al., 1999) that much of coronal heating is driven by the continuous interplay between the emergence, separation, merging, and cancellation of small-scale magnetic elements. Reconnection seems to be the most likely channel for the injected magnetic energy to be converted to heat (e.g., Priest and Forbes, 2000). Only a small fraction of the photospheric magnetic flux is in the form of open flux tubes connected to the heliosphere (Close et al., 2003). Thus, the idea has arisen that the dominant source of energy for open flux tubes is a series of stochastic reconnection events between the open and closed fields (e.g., Fisk et al., 1999; Ryutova et al., 2001; Fisk, 2003; Schwadron and McComas, 2003; Feldman et al., 2005; Schwadron et al., 2006; Schwadron and McComas, 2008; Fisk and Zhao, 2009).

The natural appeal of the RLO idea is evident from the fact that open flux tubes are always rooted in the vicinity of closed loops (e.g., Dowdy et al., 1986) and that all layers of the solar atmosphere seem to be in continual motion with a wide range of timescales. In fact, observed correlations between the lengths of closed loops in various regions, the electron temperature in the low corona, and the wind speed at 1 AU (Feldman et al., 1999; Gloeckler et al., 2003) are highly suggestive of a net transfer of Poynting flux from the loops to the open-field regions that may be key to understanding the macroscopic structure of the solar wind. The proposed RLO reconnection events may also be useful in generating energetic particles and cross-field diffusive transport throughout the heliosphere (e.g., Fisk and Schwadron, 2001).

Testing the RLO idea using theoretical models seems to be more difficult than testing the WTD idea because of the complex multi-scale nature of magnetic reconnection. It can be argued that one needs to create fully three-dimensional models of the coronal magnetic field (arising from multiple magnetic elements on the surface) to truly assess the full range of closed/open flux interactions. The idea of modeling the coronal field via a collection of discrete magnetic sources (referred to in various contexts as “magneto-chemistry,” “tectonics,” or “magnetic charge topology”) has been used extensively to study the evolution of the closed-field corona (e.g., Longcope, 1996; Schrijver et al., 1997; Longcope and Kankelborg, 1999; Sturrock et al., 1999; Priest et al., 2002; Beveridge et al., 2003; Barnes et al., 2005; Parnell, 2007; Ng and Bhattacharjee, 2008), but applications to open fields and the solar wind have been rarer (see, however, Fisk, 2005; Tu et al., 2005).

In order to develop the RLO paradigm to the point where it can be tested more quantitatively, several key questions remain to be answered. For example, how much magnetic flux actually opens up in the magnetic carpet? Also, what is the time and space distribution of reconnection-driven energy addition into the (transiently) open flux tubes? Lastly, how is the reconnection energy distributed into various forms (e.g., bulk kinetic energy in “jets,” thermal energy, waves, turbulence, and energetic particles) that each affect the accelerating solar wind in different ways? Combinations of simulations, analytic scaling relations, and observations are needed to make further progress.

5.4 Kinetic microphysics

The theoretical models discussed in the previous two subsections mainly involved a “one-fluid” or MHD approach to the coronal heating and solar wind acceleration. However, at large heights in coronal holes, the collisionless divergence of plasma parameters for protons, electrons, and heavy ions allows the multi-fluid kinetic processes to be distinguished in a more definitive way. The UVCS measurements of strong O+5 preferential heating, preferential acceleration, and temperature anisotropy have spurred a great deal of theoretical work in this direction (see reviews by Hollweg and Isenberg, 2002; Cranmer, 2002a; Marsch, 2005, 2006; Kohl et al., 2006). Specifically, the observed ordering of Ti ≫ Tp > Te and the existence of anisotropies of the form T⊥ > T∥ in coronal holes led to a resurgence of interest in models of ion cyclotron resonance.