Abstract

We show the potentiality of coupling together different compound-specific isotopic analyses in a laboratory experiment, where 13C-depleted leaf litter was incubated on a 13C-enriched soil. The aim of our study was to identify the soil compounds where the C derived from three different litter species is retained. Three 13C-depleted leaf litter (Liquidambar styraciflua L., Cercis canadensis L. and Pinus taeda L., δ13CvsPDB ≈ −43‰), differing in their degradability, were incubated on a C4 soil (δ13CvsPDB ≈ −18‰) under laboratory-controlled conditions for 8 months. At harvest, compound-specific isotope analyses were performed on different classes of soil compounds [i.e. phospholipids fatty acids (PLFAs), n-alkanes and soil pyrolysis products]. Linoleic acid (PLFA 18:2ω6,9) was found to be very depleted in 13C (δ13CvsPDB ≈ from −38 to −42‰) compared to all other PLFAs (δ13CvsPDB ≈ from −14 to −35‰). Because of this, fungi were identified as the first among microbes to use the litter as source of C. Among n-alkanes, long-chain (C27–C31) n-alkanes were the only to have a depleted δ13C. This is an indication that not all of the C derived from litter in the soil was transformed by microbes. The depletion in 13C was also found in different classes of pyrolysis products, suggesting that the litter-derived C is incorporated in less or more chemically stable compounds, even only after 8 months decomposition.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The relentless increase of atmospheric CO2 concentration stimulated a large number of studies, in the past decades, devoted to the quantification of C fluxes between the atmosphere and the terrestrial biosphere. Terrestrial biosphere was proven to be an important sink for atmospheric CO2 (Janssens et al. 2003; Luo et al. 2007; Schimel et al. 2001), with soil organic matter (SOM) being the ultimate pool in which C can be stored for centuries or millennia (Schlesinger 1997; Yadav and Malanson 2007). Understanding C dynamics in soils is, thus, a main task for scientists working on the global C cycle.

SOM is formed from the decomposition of dead plant and animal material (e.g. wood, roots, leaf litter, animal residues, etc.) due to the action of abiotic (e.g. wind, rain, solar radiation) and biotic (e.g. soil macrofauna and microbial community) factors (Aber et al. 1990; Spaccini et al. 2000). In particular, decomposition of leaf litter is one of the major processes determining SOM formation (Kuzyakov and Domanski 2000; Liski et al. 2002).

Plant biomass is a complex mixture of several polymers of very different structure (Gleixner et al. 2001). After plant death, this mixture undergoes oxidative and hydrolytic degradation by micro-organisms, accompanied by secondary structural changes. Several different steps are used in describing SOM formation, including loss of labile compounds and CO2 and numerous reactions of biotransformation of recalcitrant compounds. On the other side, undecomposed litter fragments may directly enter the soil and may prime aggregate formation (Six and Jastrow 2002). This suggests that part of litter-derived C could enter SOM without any participation by microbes. The relative importance of factors governing these processes is poorly understood. In particular, a key question is how substrate quality affects the transformations of plant residues into stable SOM (Corbeels 2001).

Mechanisms of SOM formation and stabilization have mainly been studied investigating the turnover and stability of SOM as a bulk (Zech et al. 1997). This just reveals mean pattern of soil C transformation, but it does not give any information about the phenomenon acting at the molecular level. Indeed, physical fractionation coupled with SOM labelling allowed progress in understanding changes in soil C stores, especially, the stabilization of SOM due to the interaction with the mineral part of soil (Del Galdo et al. 2003). However, to fully clarify soil C stabilization processes at the molecular level, the chemical nature of soil organic C has to be studied as well as the flow rates of each different group of compounds forming SOM need to be quantified (Gleixner et al. 2001; Lichtfouse 2000). This study focuses on three different groups of compounds:

-

Phospholipids fatty acids

-

n-Alkanes

-

Pyrolysis products

Phospholipids fatty acids

Since micro-organisms play a fundamental role in the transformation of organic residues in SOM, the study of microbial community in soil is necessary to fully understand the dynamics of C during SOM formation. To characterize soil microbial communities, the fatty acids of phospholipids belonging to the cell membranes of micro-organisms are routinely used (Allison et al. 2005; Zelles 1999). Phospholipids are essential membrane components of all living cells: because of their fast metabolization rate on cell death (Tollefson and McKercher 1983), phospholipids fatty acids (PLFAs) reflect the structure of viable soil microbial community. The PLFAs in soil are derived from a wide range of bacteria, fungi and invertebrates and present a complex mixture that is a challenge both to analyze and interpret (Zelles 1999). In many cases, specific types of fatty acids predominate in a given taxon so that they can be used to distinguish between the different groups of micro-organisms.

n-Alkanes

Yet, not all the C derived from plant material is processed by micro-organisms. Recalcitrant compounds present in plants (i.e. lipids, waxes, etc.) can be transported into the soil without being involved in microbial metabolism. For example, n-alkanes are found in leaves for a number of reasons; for instance, to protect the exposed part of outer cells against drought, plant leaves are covered with nonpermeable, hydrophobic compounds (Gleixner et al. 2001). Most of studies on n-alkanes abundance are conducted on leaves or sediments samples: n-alkanes are used as biomarkers for the paleoenvironment (Lockheart et al. 1997; Naraoka and Ishiwatari 1999). In SOM studies, the extraction of n-alkanes from SOM gives the opportunity to test the presence of compounds recalcitrant to microbial attack, derived from wax lipids of decomposing leaf litter (Cayet and Lichtfouse 2001; Lichtfouse et al. 1995a, 1994).

Pyrolysis products

The use of Curie-point pyrolysis for the thermal degradation of organic substances gives a reliable and reproducible way to obtain volatile products (i.e. benzenes, phenols, etc.) that can be related to compounds of different origin. Even if there is still great debate in the scientific community about its reliability in studies on complex material such as SOM, this technique has been successfully applied to SOM studies numerous times (Gleixner et al. 1999, 2002; Gleixner and Schmidt 1998).

The measurements of stable isotopic signature of C compounds is a very powerful tool to follow the fate of C compounds among different environmental C stocks, provided that the stocks have different C isotopic composition. In our case, the identification of SOM compounds where litter-derived C is incorporated is possible, if the original litter and SOM have different C isotopic composition (Gleixner et al. 2001; Lichtfouse et al. 1995b).

With the aim to understand how the substrate quality affects the transformation of plant residues into SOM compounds, a set of three 13C-depleted leaf litters, from three hardwood species, proven to differ for decomposability, were incubated over a C4 soil (i.e. 13C-enriched) under controlled laboratory conditions (Rubino et al. 2007). The measure of the shift in isotopic composition of different soil compounds allowed us to identify C flow processes, distinguishing between direct input and transfers mediated by bacteria and fungi and to trace the new C input to specific soil compounds (i.e. PLFAs, n-alkanes, pyrolysis products).

In a previous study referring to the same incubation experiment (Rubino et al. 2007), we suggested that, in the absence of litter fragmentation, C input to soil from microbial degradation of leaf litter is a constant (i.e. independent of litter decomposability) fraction (approximately 13%) of litter C loss, whereas the remaining fraction is lost as CO2 to the atmosphere. By comparing the fractions of litter-derived C in specific compounds of soils incubated with the different litter species, here we want to test the hypothesis that the relative importance of the processes driving the C allocation into soil compounds is independent of litter degradability.

Experimental

Soil–litter incubation experiment

For the purpose of this study, soils derived from a laboratory incubation experiment as described by Rubino et al. (2007) were used. In brief, a set of three C3 litter species (two broadleaf litters: L. styraciflua and C. canadensis and one needle litter: P. taeda) collected from the FACTS-I (Forest-Atmosphere Carbon Transfer and Storage) experiment at Duke forest (Duke University, Durham, North Carolina) were incubated on the top of a C4 soil. The soil, collected from a long-term maize field in North-Eastern Italy (46°3′34N, 12°59′8E, 77 m asl), is classified as an alluvial mesic, Udifluvent (USDA classification).

Litter samples (3 g, in four replicates) of each species were added to the incubation units containing soil samples (70 g), sieved to 2 mm, rewetted to 55% of water-holding capacity (WHC) and inoculated with a fresh soil suspension (3 ml, 1:3 water–organic soil). Four replicates of only soil were used as control systems, resulting in 16 experimental units (i.e. three litter species + soil and one soil only, all replicated four times). Each incubation unit, consisting of a 1.5-L airtight glass jar, was incubated in the dark at 20°C. For the entire duration of the experiment, on a daily basis, the jars were opened and flushed with room air to maintain aerobic conditions. Once a week, jars were weighed to determine eventual water loss. If needed, they were rewetted to the initial weight, to keep soil moisture constant. After 8 months, surface litter (the residual litter on the soil, or aboveground) was removed from each jar, carefully cleaned from soil, dried in oven (70°C) and weighed.

Soil samples were stored at −80°C until used for further analyses. For bulk soil measurements, soil subsamples, before and after the incubation, previously treated with HCl to remove carbonates, were dried and milled. Isotopic composition (δ13C [‰]vsPDB) and C content (%) for bulk soil and litter samples before and after the incubation period were measured using an elemental analyzer (ThermoFinnigan: EA 1112) coupled with an IRMS (isotope ratio mass spectrometer, ThermoFinnigan: Deltaplus). Mass and chemical characteristics of the plant and soil material prior and after incubation are reported in Table 1, after Rubino et al. (2007).

Compound-specific isotope analyses on soil sample

Soil samples derived from each jar after incubation, as well as from the initial soil, stored at −80°C, were shipped to the Max Planck Institute for Biogeochemistry, Jena (Germany), to measure the δ13C of specific compounds. δ13C analyses were run on pyrolysis products of soil samples and on n-alkanes and phospholipid fatty acids extracted from soil samples following different procedures, as described in the following paragraphs.

Compound-specific δ13C analysis of PLFA

Soil subsamples were stored frozen at −80°C prior to the extraction process, to maintain the soil microbial biomass unaltered. Following the procedure developed by Bligh and Dyer (1959) and modified by White et al. (1979), about 200 g of soil, sieved to <2 mm, were placed in a mixture of 100 ml phosphate buffer, 125 ml chloroform and 250 ml methanol (1:1.25:2.5) and shaken for 3 h overhead. Such a big amount of soil sample (ca. 200 g) is justified by the low C content of the soil used (see Table 1). To obtain the highest possible peaks, the four replicates, for each soil incubated with a different litter species, were pooled together. Then 125 ml of distilled water and 125 ml of chloroform were added, and the two phases were allowed to separate overnight. The chloroform phase, containing lipids, was reduced to a small volume by evaporation and then separated into neutral-, glycol-, phospho- (or polar) lipids using silicic acid columns by eluting with chloroform, acetone and methanol, respectively (Frostegård 1995). The fraction of phospholipids was subjected to a mild, alkaline methanolysis of phospholipids, and the resulting fatty acid methyl esters (FAMEs) dissolved in chloroform were obtained. An aminopropyl-bonded solid phase extraction (SPE-NH2) column was used to separate the saponified products into unsubstituted FAMEs, OH-substituted FAMEs and unsaponifiable lipids (Zelles et al. 1992). Furthermore, unsubstituted FAMEs were separated by benzensulphonic-acid-bonded SPE column (SPE-SCX) into saturated fatty acid (SATFA), monounsaturated fatty acid (MUFA) and polyunsaturated fatty acid (PUFA). All fractions were subjected to GC/MS-C-IRMS analysis to identify and measure the δ13C of each specific peak. Fatty acids are designated by the total number of carbon atoms; the degree of unsaturation is indicated by a number separated from the chain length number by a colon. The degree of unsaturation is followed by ωx, where x indicates the position of the double bond nearest to the aliphatic end (ω). The prefixes iso, anteiso and cyclo (cyclopropyl) refer to the type of branching in the chain.

Compound-specific δ13C analysis of n-alkanes

Extraction of n-alkanes from soil samples was obtained following the same procedure used for extraction of n-alkanes from plant leaves and from sediments (Collister et al. 1994). About 10 g of soil for each replicate was freeze-dried and pulverized. All the compounds soluble in dichloromethane–methanol (9:1) were extracted using an Accelerated Solvent Extractor (ASE200, Dionex Corp., Sunnyvale, USA) at 100°C and 2,000 psi for 15 min in two cycles. The total extract was separated on a silica-gel column into three fractions: aliphatics (solvent: hexane), aromatics (solvent: chloroform) and other compounds (solvent: methanol). Compounds of the aliphatic fraction were identified based on the comparison to an external n-alkane standard mixture and quantified using a GC-FID (Trace GC, ThermoElectron, Rodano, Italy) equipped with a DB5ms column (30 m, ID: 0.32 mm, film thickness: 0.5 μm, Agilent, Palo Alto, USA). The identification of single compounds was confirmed using a GC/MS system, and δ13C of single n-alkane was measured by means of GC/MS-C-IRMS.

Curie-point pyrolysis-gas chromatography/mass spectrometry compound-specific isotope ratio mass spectrometry (Py-GC/MS-C-IRMS)

Approximately 10 mg of dried soil, sieved to 2 mm and milled, was pyrolyzed in a Curie-point pyrolyzer (0316 Fischer, 53340 Meckeinheim, Germany) using a ferro-magnetic sample tube for 9.9 s. Pyrolysis temperature was 500°C, while interface temperature was 250°C. Following split injection, the pyrolysis products were separated on a BPX 5 column (60 m × 0.32 mm, film thickness 1.0 μm, Scientific Glass Engineering, 64331 Weiterstadt, Germany) using a temperature program of 36°C for 5 min, in 5°C min−1 to 270°C, followed by a jump (30°C min−1) to a final temperature of 300°C. The injector temperature was set to 250°C. The column outlet was coupled to a fixed splitter (split ratio 1:9). The major proportion was transferred to a combustion furnace converting the pyrolysis products to CO2, N2 and H2O (CuO, NiO and PtO set at 940°C), and the δ13C values were determined using an isotope ratio mass spectrometer (Thermofinnigan DeltaplusXL). The minor proportion of the GC elutes after the fixed splitter was transferred to an ion-trap mass spectrometer (Thermoquest GCQ). The transfer line was heated to 270°C, and source temperature was held at 180°C. Pyrolysis products were ionized by electron impact (EI) with 70 eV ionization energy and identified by comparison with reference spectra using GCQ identification software and Wiley mass spectra library (Gleixner et al. 1999, 2002; Gleixner and Schmidt 1998).

Data analysis

The determination of the fraction of litter-derived C for each soil compound over the total C in a specific soil compound was obtained by applying an isotopic mass balance to the difference between the δ13C of each soil compound for soils incubated with litters and that for the control soil, as follows:

where \( \frac{{C^{{\text{l}}}_{{\text{s}}} {\left( t \right)}}} {{C_{{\text{s}}} {\left( t \right)}}} \) is the fraction of litter-derived C in soil (\( C^{{\text{l}}}_{{\text{s}}} {\left( t \right)} \), s = soil, l = litter) over the total soil C, δ s(t) is the δ13C of the soils incubated with the litter at the end of incubation, δ c(t) is the δ13C of the control soil at the end of incubation (c = control) and δ 1(t) is the δ13C of litter sample. Main assumption with this mass balance is that the δ13C of litter-derived C compounds in soil is equal to the δ13C of the bulk litter. Furthermore, since in the case of analysis of n-alkanes, no data are available for control soil at the end of incubation (see "δ13C of n-alkanes"), δ c(t) is substituted by the δ13C of each compound in soil at the beginning of incubation. This is based on the assumption that no change in the δ13C of single n-alkanes in control soil between the beginning and the end of incubation occurred.

One-way ANOVA was used to test for significant differences among the different litter species. t tests were applied every time we want to discuss the difference between the same variable measured at the beginning and at the end of incubation. When significant differences are found, the significance level is given in parenthesis.

Results

δ13C of PLFAs

In Fig. 1, the δ13C of SATFAs, MUFAs and PUFAs (just one in our case: 18:2ω6,9) for soils incubated with the three litter species and for control soil are shown. No data are available from soil at the beginning of incubation, because the soil used had been air-dried, rewetted and an inoculum was added to activate its microbial biomass (Rubino et al. 2007).

δ13CvsPDB of SATFAs (left plot), MUFAs and PUFAs (18:2ω6, right plot) for control soil (open square) and soil incubated with L. styraciflua (filled circle), with C. canadensis (open circle) and with P. taeda (open triangle). Error bars are standard deviation, n = 3 analytical replicates. Note the 13C depletion of soil incubated with litters compared to the control soils (see arrows)

The δ13C of SATFAs for control soil ranged around the δ13C of bulk control soil (−17.7 ± 0.3‰, Table 1). The δ13C of SATFAs for each soil incubated with litter follows the same trend of the control soil, but they are all (except 14:0 of soil incubated with P. taeda) significantly more negative than that of control soil (P < 0.01). In particular, soil incubated with L. styraciflua shows the most negative values, followed by that incubated with C. canadensis. The δ13C of all MUFAs (except 16:1ω7) for control soil is more positive than the δ13C of bulk control soil (P < 0.01). Like for SATFAs, the trend of δ13C of MUFAs for each soil incubated with litter is similar to that of control soil. Also in this case, they are all more negative in comparison to the control soil.

Based on a classification referring to the group of micro-organisms PLFAs are formed by (see also Table 3), branched SATFAs (characteristic of Gram-positive bacteria) had a more positive δ13C (−24.6 ± 0.7‰, −22.9 ± 1.0‰ and −19.3 ± 0.9‰ for soil incubated with L. styraciflua, C. canadensis and P. taeda, respectively, errors are standard errors over four replicates) than cyclopropyl SATFAs (typical of Gram-negative bacteria: −33.8 ± 1.0‰, −32.1 ± 0.7‰ and −27.0 ± 0.8‰ for soil incubated with L. styraciflua, C. canadensis and P. taeda, respectively, P < 0.01). Straight chain MUFAs (characteristic of Gram-negative bacteria) were significantly depleted in 13C than branched SATFAs only in the case of soil incubated with L. styraciflua (δ13C: −27.0 ± 1.3‰, P < 0.05), whereas in soils incubated with C canadensis and P. taeda, this was not the case (δ13C: −22.4 ± 2.6‰ and −20.3 ± 0.9‰, respectively). Cyclo SATFAs were significantly depleted in 13C than straight chain MUFAs (P < 0.01).

The only PUFA we found (18:2ω6,9, a marker for fungi) is very depleted in 13C for all soils incubated with litter, with δ13C of −42.0 ± 0.4‰, −38.4 ± 0.3‰ and −38.4 ± 0.1‰ for soils incubated with L. styraciflua, C. canadensis and P. taeda, respectively, with respect to that of control soil (δ13C of −19.8 ± 1.1‰, Fig. 1).

δ13C of n-alkanes

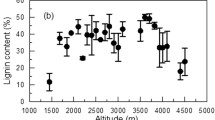

The δ13Cs of n-alkanes (C14–C32) for soils incubated with each litter species are shown in Fig. 2. The δ13Cs of n-alkanes from soil prior to incubation are also shown. Unfortunately, for a technical problem during extraction, the control soil was lost. However, we believe that the soil prior to incubation can be considered a good reference to determine the contribution of litter-derived C to n-alkanes. Here, the assumption is that n-alkanes in the control soil do not change their isotopic composition during the incubation. This will be further discussed below.

δ13C values [‰]V-PDB of n-alkanes for initial soil (open square) and soil incubated with L. styraciflua (filled circle), with C. canadensis (open circle) and with P. taeda (open triangle). Error bars are standard deviation (n = 3 analytical replicates for initial soil and n = 4 experimental replicates for soils incubated with litter)

n-Alkanes from soil prior to incubation are 10–13‰ more depleted in 13C than the bulk soil. By comparing the δ13C of n-alkanes for soils incubated with litters to the δ13C of n-alkanes for initial soil, a general trend emerges: short chain n-alkanes (i.e. C16–C22) have a δ13C not statistically different from those of initial soil, whereas long chain n-alkanes (i.e. C27–C32) are significantly depleted in 13C compared to initial soil. This is not true only for C29 of soil incubated with P. taeda (see Fig. 2; C27: P < 0.05 for all soils; C29: P < 0.01 for soils incubated with L. styraciflua and C. canadensis; C31: P < 0.01 for soils incubated with L. styraciflua and C. canadensis, while P < 0.05 for soil incubated with P. taeda).

δ13C of Curie-point pyrolysis products

Pyrolysis products of Py-GC/MS-C-IRMS are classified in Table 2 with regards to the compounds they are derived from (column “Origin” in Table 2). Most of the pyrolysis products are derived from polysaccharides. A general enrichment in 13C of compounds from control soil at the end of the incubation in comparison to soil prior to incubation is evident. But this is significant only for three compounds (cyclopent-3-en-1-one, 3-furaldehyde and 5-methyl-2-furaldehyde, significance levels are given by asterisks in Table 2: **P < 0.01, *P < 0.05). On the contrary, compounds for soils incubated with litters are generally depleted in 13C, compared to both the initial soil and the control soil (Table 2). However, only six compounds for L. styraciflua [benzene, cyclopent-3-en-1-one, 1H-pyrrole + (pyridine), 3-furaldehyde, 2-furaldehyde, 5-methyl-2-furaldehyde], seven compounds for C. canadensis [benzene, cyclopent-3-en-1-one, 1H-pyrrole + (pyridine), 3-furaldehyde, 2-furaldehyde, o-xylene + styrene, 5-methyl-2-furaldehyde] and four compounds for P. taeda (benzene, cyclopent-3-en-1-one, 3-furaldehyde, 5-methyl-2-furaldehyde) are significantly depleted in 13C compared to control soil.

Litter-derived C in specific soil compounds

As explained in the “Data analysis” section, by applying an isotopic mass balance, the percentages of litter-derived C in each soil compound (over the total soil C contained in that specific compound) can be estimated. It is thus possible to compare the relative fractions of litter-derived C among soil incubated with different litters or among different compounds in the same soil. Comparisons of the absolute amount of litter-derived C in different compounds are possible only assuming an equal soil C content in each specific compound for all the soils incubated with different litter species. This assumption will be further discussed in the following section. Results for groups of PLFAs are shown in Table 3.

Different PLFAs are grouped with regard to the prevalent class of micro-organisms they are formed by (see the “Discussion” for details): branched SATFA are characteristic of Gram-positive bacteria; cyclopropyl SATFA and straight chain MUFA are mainly formed by Gran-negative bacteria; MUFA 18:1ω9 and PUFA 18:2ω6,9 are mostly found in fungi. As a general trend, percentages of litter-derived C are higher for soil incubated with L. styraciflua and lower for soil incubated with P. taeda, but the differences are not always statistically significant. On the other side, the highest percentages of litter-derived C are found for PLFAs characteristic of fungi (P < 0.01). Cyclopropyl SATFA show percentages higher than both straight chain MUFA and branched SATFA (P < 0.01). The latter two are not significantly different. Percentages of litter-derived C in n-alkanes were determined only for those n-alkanes (i.e. C27, C29, C31) where a significant shift of the δ13C occurred between the beginning and the end of the incubation, and they are reported in Table 4.

Apart from C29 in C. canadensis, there is a general decrease in the percentage of litter-derived C going from L. styraciflua to C. canadensis and P. taeda. Finally, for compounds obtained from the pyrolysis of soils, the percentages of litter-derived C varied considerably, and in general, there were no statistically significant differences between the percentages of litter-derived C in all soils incubated with each litter species [with the exception of cyclopent-3-en-1-one and 1H-pyrrole + (pyridine) of soil incubated with L styraciflua], which show significantly higher fractions of litter-derived C in comparison to the corresponding compounds in soil incubated with P. taeda (Table 5, P < 0.05).

Discussion

This study provides qualitative analyses of the fluxes of C between leaf litter and SOM, during leaf litter decay. Comparisons between soils incubated with different litter species are possible on the assumption that the amount of C in each compound is the same for all soils. We believe this to be a reasonable assumption, since the same soil was used for all the incubation and the amount of litter-derived C input in the soil at the end of the incubation was negligible if compared to the total amount of C present in the SOM (Rubino et al. 2007).

Additionally, it is worth to stress that these results could be mislead by processes of isotopic fractionation occurring during the degradation of the organic material (Fernandez et al. 2003; Santruckova et al. 2000). As suggested by past studies (Fernandez and Cadish 2003; Fernandez et al. 2003), a fractionation of only few unities of ‰ is likely to occur. In our experiment, the δ13C of the litter substrates did not significantly change during the incubation (see Table 1), thus, supporting the hypothesis that, if an isotopic fractionation was present, it was not greater than few unities of ‰. Since we used labelled 13C-depleted litter on a 13C-enriched C4 soil, such a variation in δ13C could be considered negligible if compared to the difference in δ13C between the two endmembers (Δδ13C ≈ 26‰).

PLFA

Our results, by showing that the δ13C of SATFA, MUFA and PUFA for all soils incubated with litter was more negative than that of control soil, testified an incorporation of litter-derived C in soil microbial biomass (Fig. 1). On average, branched SATFAs had a more positive δ13C than cyclopropyl SATFAs (cyclo SATFAs). Usually, branched SATFAs are used as biomarkers for Gram-positive bacteria (Bardgett et al. 1999; Feng et al. 2002), whereas cyclo SATFAs and straight chain MUFAs are generally characteristic of Gram-negative bacteria (Ratledge and Wlkinson 1988; Zelles 1997). Thus, our results would indicate a higher assimilation of litter-derived C by some Gram-negative than by Gram-positive bacteria. Among all the PLFAs, the PUFA 18:2ω6,9 (linoleic acid) showed the highest percentages of litter-derived C (Table 3). Linoleic acid (18:2ω6,9) is considered as an indicator fatty acid for fungi (Frostegård and Bååth 1996), but it is also one of the major fatty acids in the plant kingdom (Hitchcock 1975). Thus, this fatty acid is a good indicator for fungi when plant cells are not present in the system. In our system, only dead plant cells may have entered the SOM from litter material. Dead plant cells into SOM can be assumed to be readily hydrolyzed (Tollefson and McKercher 1983). For this reason, we suggest that, in our systems, litter-derived C assimilation by fungi was higher than that by bacteria. This is in agreement with Frey et al. (2003), who demonstrated that fungi were the mediators of the transfer of C from decomposing litter to soil and of nitrogen from soil to litter. However, the more negative δ13C value measured for the linoleic acid in soils incubated with litter, when compared to other PLFAs, may also be interpreted as a spatial–temporal dynamics (Dilly 2001) of microbial incorporation of litter-derived C. Thanks to their filamentous hyphae, fungi can grow on the substrate (litter) and they can be the first to take up C from the leaves and to introduce it into the soil, where it would then be assimilated by other soil micro-organisms. Our hypothesis is also supported by high litter C percentages found in the MUFA 18:1ω9, which is often considered characteristic of fungi (Bardgett et al. 1999; Feng et al. 2002).

n-Alkanes

There are several previous investigations focusing on long chain n-alkanes as biochemically stable compounds in soil derived from plants (Cayet and Lichtfouse 2001; Lichtfouse et al. 1994). In our systems, litter-derived n-alkanes could enter the soil by physical transport, from the decaying litter into the underlay soil. It is unlikely to assume any process of incorporation of C in n-alkanes mediated by micro-organisms (Huang 1999). Assuming no variation in the isotopic composition of n-alkanes in soil from the beginning to the end of the incubation (so that the soil at the beginning of incubation can be used as a reference), a depletion in the isotopic composition of n-alkanes with higher C number was a proof of incorporation of litter-derived long chain n-alkanes in the soil. On the contrary, short chain n-alkanes in soils incubated with all litter species do not change their δ13C in comparison to the initial soil (Fig. 2). Besides giving us the proof that short chain n-alkanes in the soil were not derived from the litter, this result supports the validity of the assumption of no change in the δ13C of n-alkanes between the beginning and the end of the incubation. The assumption is, however, theoretically supported by the biochemical and, as a consequence, isotopic stability of this class of compounds (Huang et al. 1997; Lichtfouse et al. 1997, 1998).

As in the case of PLFA, the application of the isotopic mass balance allowed the determination of the fraction of litter-derived C in n-alkanes (Table 4). This was possible only for n-alkanes isotopically depleted in comparison to the control soil (i.e. C27–C31) that have also been previously described as tree-specific biomarkers (Eglinton et al. 1997). As for PLFAs, very different percentages of litter-derived C were measured for each soil incubated with different litter species, but except for C29, the highest fractions of litter-derived C for each n-alkane were found for soil incubated with L. styraciflua. On the other hand, soil incubated with P. taeda showed the lowest percentages of litter-derived C (Table 4). Thus, it seems that the quantity of C lost as n-alkane C could be proportional to the total C lost by each litter in the soil that is the highest for L. styraciflua and the lowest for P. taeda. This would mean that the factors influencing the n-alkane C loss appear to be the same affecting the total C loss.

However, since we did not extract n-alkanes from leaves (because we did not have enough litter material), an isotopic mass balance for n-alkanes may be biased because of the difference between the δ13C of n-alkanes and that of bulk litter material. Usually n-alkanes extracted from leaves are depleted in 13C compared to bulk material (Collister et al. 1994; Rieley et al. 1991). If this were true in our case, our measured litter-derived C fractions for each n-alkane should be higher than the correct values. In other words, our esteem of litter-derived C fractions could be overestimated. Nonetheless, assuming the same differences in δ13C between n-alkanes and bulk leaves material, the error (expressed as percent of the measured value) we introduce is equal for each species so that the comparison between litter-derived C fractions for soils incubated with different litter species still holds.

Pyrolysis products

In our experiment, pyrolysis products of control soil became enriched in 13C at the end of the incubation. Since no external C source was present, this δ13C shift could be the result of some isotopic fractionation occurring during microbial breakdown of humic substances. A way to test this hypothesis is by measuring the δ13C of the CO2 respired by microbes in control soil. Since soil pyrolysis products are found to be 13C-enriched at the end of incubation, if this is the result of isotopic fractionation associated to respiratory processes, the CO2 respired by the control soil during incubation should be 13C-depleted, with respect to bulk δ13C values. During the incubation period, the δ13C of the CO2 respired by the control soil showed a trend, going from more positive values (ca. −16‰) at the beginning of the incubation towards more negative values (ca. −22‰) at later samplings (Rubino et al. 2007). This trend was interpreted to mirror the trend of temporal decomposition of different compounds with different δ13C, but could hide some fractionation due to microbial metabolism. In any case, as already suggested, this fractionation would not be greater than few unities of ‰ (Fernandez and Cadish 2003; Fernandez et al. 2003).

For soils incubated with litter samples, the observed depletion in 13C of pyrolysis compounds clearly indicated an incorporation of litter-derived C in these compounds, independently of their origin (microbiologically mediated or direct input in SOM from leaves). The depletion was mostly found for compounds derived from polysaccharides, but also for some of those derived from aromatic compounds (Table 2), suggesting that, even after only 8 months of decomposition, the litter-derived C can be found in less and more chemically stable classes of compounds.

As for PLFA and n-alkanes, the fractions of litter-derived C for each pyrolysis compound generally decrease going from L. styraciflua to C. canadensis and P. taeda (Table 5). Since the C lost by the litter decreased in the same order (L. styraciflua > C. canadensis > P. taeda), this is just a first qualitative suggestion that the quantity of C lost in each compound could be proportional to the total C lost by each litter species, and there is no dependence of the percentage of C lost by litter in each specific compound on the litter liability.

Conclusions

The variation in the degree of assimilation of litter C compounds between microbial biomarkers suggests that among the different groups of micro-organisms, fungi are the first to colonize the litter and act the transfer of C from the litter layer into the soil. To better understand the microbial succession in the decomposers community, different studies, with a higher number of destructive replicates, should be planned.

A general depletion in δ13C of long chain n-alkanes testifies an incorporation of litter C in soil that could not be mediated by micro-organisms. In our systems, this is probably due to the contact between litter and soil surface at the soil–litter interface. Direct incorporation of litter compounds into soil maybe a significant component of the C flow belowground, and given the persistence of n-alkanes in soils, it may also be significant in terms of C sequestration below ground.

With regard to the control soil pyrolysis products, an isotopic discrimination was found. Too little is currently known about isotopic discrimination during SOM decomposition, yet our results strongly suggest that it may well occur: future research should be devoted to clarify this issue, given the greater and greater number of studies on SOM dynamics using isotopic methodologies.

The fractions of litter-derived C for each compound in soils incubated with all litter species decreased almost always in the order: L. styraciflua > C. canadensis > P. taeda that is the same order of total C lost. This is just a first, qualitative suggestion that the proportion of litter-derived C incorporated in each compound of soil is not dependent on litter degradability. Effort is needed now to quantitatively determine the relative contribution of each component process. Additionally, the residence time of the individual litter-derived SOC compounds should be estimated.

References

Aber JD, Melillo JM, McClaugherty CA (1990) Predicting long-term patterns of mass loss, nitrogen dynamics, and soil organic matter formation from initial fine litter chemistry in temperate forest ecosystem. Can J Bot 68:2201–2208

Allison VJ, Miller RM, Jastrow JD, Matamala R, Zak DR (2005) Changes in soil microbial community structure in a tallgrass prairie chronosequence. Soil Sci Soc Am J 69:1412–1421

Bardgett RD, Kandeler E, Tscherko D, Hobbs PJ, Bezemer TM, Jones TH, Thompson LJ (1999) Below-ground microbial community development in a high temperature world. Oikos 85(2):193–203

Bligh EG, Dyer WJ (1959) A rapid method of total lipid extraction and purification. Can J Biochem Physiol 37:911–917

Cayet C, Lichtfouse E (2001) δ13C of plant-derived n-alkanes in soil particle-size fractions. Org Geochem 32:253–258

Collister JW, Rieley G, Stern B, Eglinton G, Fry B (1994) Compound-specific δ13C analyses of leaf lipids from plants with differing carbon dioxed metabolisms. Org Geochem 21:619–627

Corbeels M (2001) Plant litter and decomposition: general concepts and model approaches. Paper presented at the NEE Workshop Proceedings, Canberra, Australia, 18–20 April 2001

Del Galdo I, Six J, Peressotti A, Cotrufo MF (2003) Assessing the impact of land-use change on soil C sequestration in agricultural soils by means of organic matter fractionation and stable C isotopes. Global Change Biol 9:1204–1213

Dilly O, Bartsch S, Rosenbrock P, Buscot F, Munch JC (2001) Shifts in physiological capabilities of the microbiota during the decomposition of leaf litter in a black alder (Alnus glutinosa (Gaertn.) L.) forest. Soil Biol Biochem 33:921–930

Eglinton TI, Benitez-Nelson BC, Pearson A, McNichol AP, Bauer JE, Druffel ERM (1997) Variability in radiocarbon ages of individual organic compounds from marine sediments. Science 277(5327):796–799

Feng Y, Motta AC, Burmester CH, Reeves DW, van Santen E, Osborne JA (2002) Effects of tillage systems on soil microbial community structure under a continuous cotton cropping system. In: Santen EV (ed) Proceedings of 25th annual southern conservation. Tillage conference for sustainable agriculture making conservation tillage conventional: building a future on 25 years of research. Alabama Agricultural Experiment Station and Auburn University, Auburn, USA

Fernandez I, Cadish G (2003) Discrimination against 13C during degradation of simple and complex substrates by two white rot fungi. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom 17:2614–2620

Fernandez I, Mahieu N, Cadish G (2003) Carbon isotopic fractionation during decomposition of plant materials of different quality. Global Biogeochem Cycles 3:1075–1086

Frey SD, Six J, Elliott ET (2003) Reciprocal transfer of carbon and nitrogen by decomposer fungi at the soil–litter interface. Soil Biol Biochem 35:1001–1004

Frostegård A (1995) Phospholipid fatty acid analysis to detect changes in soil microbial community structure. Lund University, Sweden

Frostegård A, Bååth E (1996) The use of phospholipids analysis to estimate bacterial and fungal biomass in soils. Biol Fertil Soils 22:59–65

Gleixner G, Schmidt HL (1998) On-line determination of group specific isotope ratios in model compounds and acquatic humic substances by coupling pyrolysis to GC-C-IRMS. In: Stankiewics BA, van Berger PF (eds) 214th National Meeting of the American Chemical Society. American Chemical Society, Las Vegas, pp 34–45

Gleixner G, Bol B, Balesdent J (1999) Molecular insight into soil carbon turnover. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom 13:1278–1283

Gleixner G, Czimczik CJ, Kramer C, Lühker B, Schmidt WIM (2001) Plant compounds and their turnover and stability as soil organic matter. In: Schulze ED, Heimann M, Harrison S, Holland E, Lloyd J, Prentice C, Schimel D (eds) Global biogeocemical cycles in the climate system. Academic Press, San Diego, pp 201–215

Gleixner G, Poirer N, Bol R, Balesdent J (2002) Molecular dynamics of organic matter in a cultivated soil. Org Geochem 33:357–366

Hitchcock C (1975) Structure and distribution of plant acyl lipids. In: Galliard T, Mercer EI (eds) Recent advances in the chemistry and biochemistry of plant lipids. Academic Press, London, pp 1–19

Huang Y, Eglinton G, Ineson P, Latter PM, Bol R, Harkness DD (1997) Absence of carbon isotopic fractionation of individual n-alkanes in 23-year field decomposition experiment with Calluna vulgaris. Org Geochem 26:497–501

Huang Y, Li B, Bryant C, Bol R, Eglinton G. (1999) Radiocarbon dating of aliphatic hydrocarbons: a new approach for dating the passive fraction carbon in soil horizons. Soil Sci Soc Am J 63:1181–1187

Janssens IA, Freibauer A, Ciais P, Smith P, Nabuurs GJ, Folberth G, Schlamadinger B, Hutjes RWA, Ceulemans R, Schulze ED, Valentini R, Dolman AJ (2003) Europe’s terrestrial biosphere absorbs 7 to 12% of European anthropogenic CO2 emissions. Science 300:1538–1542

Kuzyakov Y, Domanski G (2000) Carbon input by plants into the soil. Review. J Plant Nutr Soil Sci 163:421–431

Lichtfouse E (2000) Compound-specific isotope analysis. Application to archaeology, biomedical sciences, biosynthesis, environment, extraterrestrial chemistry, food science, forensic science, humic substances, microbiology, organic geochemistry, soil science and sport. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom 14:1337–1344

Lichtfouse E, Bardoux G, Mariotti A, Balesdent J, Ballentine DC, Macko SA (1997) Molecular, 13C and 14C evidence for the allochthonous and ancient origin of C16–C18 n-alkanes in modern soils. Geochim Cosmochim Acta 61:1891–1898

Lichtfouse E, Berthier G, Houo S, Barriuso E, Bergheaud V, Vallaeys T (1995a) Stable carbon isotope evidence for the microbial origin of C14–C18 n-alkanoic acids in soils. Org Geochem 23:849–852

Lichtfouse E, Chenu C, Baudin F, Leblond C, Da Silva M, Behar F, Derenne S, Largeau C, Wehrung P, Albrecht P (1998) A novel pathway of soil organic matter formation by selective preservation of resistant straight-chain biopolymers—chemical and isotope evidence. Org Geochem 28:411–415

Lichtfouse E, Dou S, Girardin C, Grably M, Balesdent J, Behar F, Vanderbroucke M (1995b) Unexpected 13C-enrichment of organic components from wheat crop soils. Org Geochem 23:865–868

Lichtfouse E, Elbisser B, Balesdent J, Mariotti A, Bardoux G (1994) Isotope and molecular evidence for direct input of maize leaf wax n-alkanes into crop soils. Org Geochem 22(2):349–351

Liski J, Perrochoud D, Karjalainen T (2002) Increasing carbon stocks in the forest soils of western Europe. For Ecol Manage 169:159–175

Lockheart MJ, Van Bergen PF, Evershed RP (1997) Variations in the stable carbon isotope compositions of individual lipids from the leaves of modern angiosperms: implications for the study of higher land plant-derived sedimentary organic matter. Org Geochem 26:137–153

Luo HY, Oechel WC, Hastings SJ, Zulueta R, Qian YH, Kwon H (2007) Mature semiarid chaparral ecosystems can be a significant sink for atmospheric carbon dioxide. Global Change Biol 13(2):386–396

Naraoka H, Ishiwatari R (1999) Carbon isotopic compositions of individual long-chain n-fatty acids and n-alkanes in sediments from river to open ocean: multiple origins for their occurrence. Geochem J 33:215–235

Ratledge C, Wlkinson SG (1988) Microbial lipids. Academic Press, London

Rieley G, Collister JW, Jones DM, Eglinton G, Eakin PA, Fallick AK (1991) Source of sedimentary lipids deduced from stable carbon isotope analyses of individual compounds. Nature 352:425–427

Rubino M, Lubritto C, D’Onofrio A, Terrasi F, Gleixner G, Cotrufo MF (2007) An isotopic method for testing the influence of leaf litter quality on carbon fluxes during decomposition. Oecologia 154:155–166

Santruckova H, Bird MI, Lloyd J (2000) Microbial processes and carbon-isotope fractionation in tropical and temperate grassland soils. Funct Ecol 14:108–114

Schimel DS, House JI, Hibbard KA, Bousquet P, Ciais P, Peylin P, Braswell BH, Apps MJ, Baker D, Bondeau A, Canadell J, Churkina G, Cramer W, Denning AS, Field CB, Friedlingstein P, Goodale C, Heimann M, Houghton RA, Melillo JM, MooreIii B, Murdiyarso D, Noble I, Pacala SW, Prentice IC, Raupach MR, Rayner PJ, Scholes RJ, Steffen WL, Wirth C (2001) Recent patterns and mechanisms of carbon exchange by terrestrial ecosystems. Nature 414:169–172

Schlesinger WH (1997) Biogeochemistry—an analysis of global change. Academic Press, San Diego, p 588

Six J, Jastrow JD (2002) Soil organic matter turnover. Marcel Dekker, NY, pp 936–942

Spaccini R, Piccolo A, Haberhauer G, Gerzabek MH (2000) Transformation of organic matter from maize residues into labile and humic fractions of three European soils as revealed by 13C distribution and CPMAS-NMR spectra. Eur J Soil Sci 51:583–594

Tollefson TS, McKercher RB (1983) The degradation of 14C-labelled phosphatidyl choline in soil. Soil Biol Biochem 15(2):145–148

White DC, Davis WM, Nickels JS, King JD, Bobbie RJ (1979) Determination of sedimentary microbial biomass by extractable lipid phosphate. Oecologia 40:51–62

Yadav V, Malanson G (2007) Progress in soil organic matter research: litter decomposition, modelling, monitoring and sequestration. Prog Phys Geogr 31(2):131–154

Zech W, Senesi N, Guggenberger G, Kaiser K, Lehmann J, Miano TM, Miltner A, Schroth G (1997) Factors controlling humification and mineralization of soil organic matter in the tropics. Geoderma 79(1–4):117–161

Zelles (1999) Fatty acid patterns of phospholipids and lipopolysaccharides in the characterization of microbial community in soil: a review. Biol Fertil Soils 29:111–129

Zelles L (1997) Phospholipids fatty acid profiles in selected members of soil microbial communities. Chemosphere 35(112):275–294

Zelles L, Bay QY, Beck T, Beese T, Beese F (1992) Signature fatty acids in phospholipids and lipopolysaccharides as indicators of microbial biomass and community structure in agricultural soils. Soil Biol Biochem 24:317–323

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the ESF -SIBAE program and by the CARBOEUROPE IP and co-financed by Legge 5, Regione Campania, Italy. We like to thank S. Rühlow and S. Lenk for excellent technical assistance during sample preparation and GC/MS-C-IRMS analysis and Dirk Sachse and Sibylle Steinbeiss for their help with the laboratory work. Further we like to thank Prof. William Schlesinger for provision of the litter material, and Dr. Alessandro Peressotti for provision of the C4 soil.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0 ), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Rubino, M., Lubritto, C., D’Onofrio, A. et al. Isotopic evidences for microbiologically mediated and direct C input to soil compounds from three different leaf litters during their decomposition. Environ Chem Lett 7, 85–95 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10311-008-0141-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10311-008-0141-6