-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Paola Frati, Vittorio Fineschi, Mariantonia Di Sanzo, Raffaele La Russa, Matteo Scopetti, Filiberto M. Severi, Emanuela Turillazzi, Preimplantation and prenatal diagnosis, wrongful birth and wrongful life: a global view of bioethical and legal controversies, Human Reproduction Update, Volume 23, Issue 3, May-June 2017, Pages 338–357, https://doi.org/10.1093/humupd/dmx002

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Prenatal diagnosis based on different technologies is increasingly used in developed countries and has become a common strategy in obstetric practice. The tests are crucial in enabling mothers to make informed decisions about the possibility of terminating pregnancy. They have generated numerous bioethical and legal controversies in the field of ‘wrongful life’ claims (action brought by or on behalf of a child against the mother or other people, claiming that he or she has to endure a not-worth-living existence) and ‘wrongful birth’ claims (action brought by the mother or parents against the physician for being burdened with an unwanted, often disabled child, which could have been avoided).

The possibility which exists nowadays to intervene actively by programming and deciding the phases linked to procreation and birth has raised several questions worldwide. The mother's right to self-determination could be an end but whether or not this right is absolute is debatable. Freedom could, with time, act as a barrier that obstructs intrusion into other people's lives and their personal choices. Therapeutic choices may be manageable in a liberal sense, and the sanctity of life can be inflected in a secular sense. These sensitive issues and the various points of view to be considered have motivated this review.

Literature searches were conducted on relevant demographic, social science and medical science databases (SocINDEX, Econlit, PopLine, Medline, Embase and Current Contents) and via other sources. Searches focused on subjects related to bioethical and legal controversies in the field of preimplantation and prenatal diagnosis, wrongful birth and wrongful life. A review of the international state of law was carried out, focusing attention on the peculiar issue of wrongful life and investigating the different jurisdictional solutions of wrongful life claims in a comparative survey.

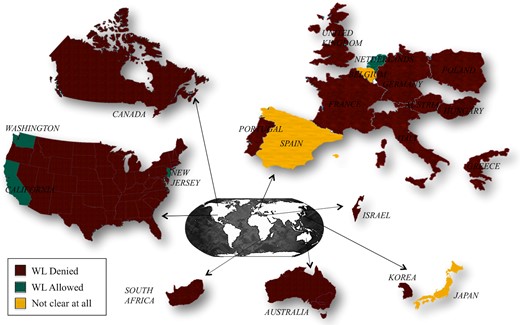

Courts around the world are generally reluctant to acknowledge wrongful life claims due to their ethical and legal implications, such as existence as an injury, the right not to be born, the nature of the harm suffered and non-existence as an alternative to a disabled life. Most countries have rejected such actions while at the same time approving those for wrongful birth. Some countries, such as France with a law passed in March 2002, have definitively excluded Wrongful Life action. Only in the Netherlands and in three states of the USA (California, Washington and New Jersey) Wrongful Life actions are allowed. In other countries, such as Belgium, legislation is unclear because, despite a first decision of the Court allowing Wrongful Life action, the case is still in progress. There is a complete lack of case law regarding wrongful conception, wrongful birth and wrongful life in a few countries, such as Estonia.

The themes of ‘wrongful birth’ and ‘wrongful life’ are charged with perplexing ethical dilemmas and raise delicate legal questions. These have met, in various countries and on certain occasions, with different solutions and have triggered ethical and juridical debate. The damage case scenarios result from a lack of information or diagnosis prior to the birth, which deprives the mother of the chance to terminate the pregnancy.

Introduction

Prenatal diagnosis (PD) using different technologies (foetal ultrasonography, genetic screening, laboratory tests, etc.) is increasingly used to explore the health and genetic conditions of unborn children and to inform expectant mothers of potential foetal anomalies and diseases that may create physical, psychological, and social harm to parents and families. In developed countries, there has been truly outstanding progress in prenatal diagnostic methods. These, however, have generated numerous bioethical and legal controversies and issues (Pelias, 1986; Strong, 2003; Crockin, 2005; Chervenak and McCullough, 2011; Amagwula et al., 2012; Chadwick and Childs, 2012; Berceanu et al., 2014; de Jong et al., 2015; Dondorp and van Lith, 2015).

When introduced, prenatal investigations such as invasive genetic diagnosis (Druzin et al., 1993), second-trimester ultrasound screening (Chervenak et al., 1989), and first-trimester risk assessment (Chasen et al., 2001) appeared controversial. They have since, however, become common strategies in obstetric practice (Ewigman et al., 1990; Wald, 2002; O'Brien et al., 2015).

Several parties are directly involved in prenatal diagnostic practice, i.e. the mother/parents, the foetus or newborn and finally the perinatal medicine practitioners.

Unlike the majority of diagnostic activities in medicine, the conditions, in most cases, cannot be cured or alleviated. Following an undesired result, the only option therefore is to decide whether to accept the child's condition and prepare for the birth or to terminate the pregnancy (Gekas et al., 2016). Consequently, the main reason for offering prenatal genetic testing is to enhance the reproductive autonomy of the woman and/or couple with regard to parenting or preventing the birth of a child with a serious disorder or disability (DiSilvestro, 2009; Schmitz et al., 2009; Wright and Chitty, 2009; Deans et al., 2015; Wilkinson, 2015). In other words, PD technologies are crucial to enable mothers to make an informed decision as to whether or not to terminate the pregnancy (Hewison, 2015).

From another point of view, the duty to give appropriate information in order to obtain informed consent is placed on the medical professionals. The question, in fact, arises as to whether or not physicians are obliged: to disclose the availability of prenatal tests to eligible patients as part of the physician–patient discussion about prenatal screening and diagnosis, to explain the risk of false-positive and false-negative test results and the uncertain implications of results and finally, to fully inform the patient about the results of the tests themselves. It is presumed that new medical techniques in the area of prenatal testing are used to give a pregnant patient as much information as possible concerning the health of her foetus. What course of action is taken thereafter is left entirely up to the patient and is essentially a personal choice. Giving the mother/parents the opportunity to make such a decision based on all of the available, accurate information is the primary responsibility of the prenatal counsellor. If an error occurs in giving or interpreting the test, the physician may be faced with an extremely delicate situation, engaging his/her moral and legal responsibility. Mothers/parents who seek prenatal counselling expect to receive accurate information regarding the health of the foetus. If they are reassured by a medical practitioner as to the health of the foetus and the child is subsequently born with an anomaly or disease, the parents have effectively been deprived of their right to make an informed decision about whether to terminate or continue the pregnancy. Failure may occur by omission or failed communication of pertinent information to the parents or by an alleged error in the interpretation of the diagnostic information (Klein and Mahoney, 2007; Frati et al., 2014; Toews and Caulfield, 2014).

In this article, we firstly explore the bioethical debate surrounding the issue of preimplantation genetic diagnosis (PGD) and PD. We then focus on the peculiar issues of wrongful birth and wrongful life, investigating the different jurisdictional solutions of wrongful life claims in a comparative survey, and laying bare some of the ethical issues involved. Finally, the ethical views regarding these controversial matters are delineated. This review suggests new frontiers for obstetric decision-making.

When we discuss maternal and foetal interests in an ethical context, one of the most critical issues is that of balancing the mother's right to self-determination and autonomy with the best interests of the unborn child (Munthe, 2015). Ethical dilemmas arise from what are often described as ‘maternal–foetal conflicts’ (Mahowald, 1993; Steinbock, 1994).

Firstly, as part of the bioethical debate underlines, this locution perpetuates the premise that the foetus, like the pregnant woman, is a person, whose interests and rights must be protected (Flagler et al., 1997). Again, the expression ‘maternal–foetal conflicts’ evokes an opposition between maternal and foetal rights and seems to imply that the nature and status of the foetus are not in doubt.

Upon birth, a baby is considered to acquire both moral and legal standing as a separate person. However, prior to birth, does the foetus have independent interests from the mother? Can it claim rights against its mother? Foetal rights doctrines grant implicit legal status to the unborn child, assuming that the foetus is a full human being from the moment of conception. Other opposing positions accord the foetus no moral or legal standing (Isaacs, 2003). Only if the foetus is considered a person, can rights and conflicts with another person, like the mother, arise. There can be no conflict without rights (Yeo and Lim, 2011). What constitutes a right is a further complex question (Savulescu, 2002; Hafner, 2011). If we assume that the foetus is a person and that foetal rights exist, women's and foetal rights may be difficult to reconcile, making it possible for the rights of a zygote, embryo or foetus to trump those of a pregnant woman in certain circumstances (Uberoi and de Bruyn, 2013). Taking the opposite view, others argue that a foetus has no moral status independent of its mother (Isaacs, 2003).

In this context, we believe that it is critical to distinguish between the legal and moral rights of the foetus and the concept of ‘best interest’ of both mother and unborn child. In making the complex link between rights and interests, it could be stressed that rights protect interests (Savulescu, 2002). An example immediately comes to mind, the right not to be born would exists if a child had an interest in not being born (Jecker, 2012). In the framework of ethical dilemmas that arise during pregnancy, some argue that there can be opposition between maternal and foetal rights, as the autonomy and self-determination of most women may conflict with the ‘best interest of the foetus’. If, in recent decades, respect for the autonomy and self-determination of all people (including pregnant women) has become an accepted ethical principle in every field of medicine, it appears to be inextricably linked with the principle of beneficence (and that of non-maleficence), presuming that everyone (pregnant woman, couples and physicians) act in the best interests of the foetus. In general, we can say that the pregnant woman makes decisions that are ‘in the interests’ of the foetus and, prospectively, of the child (Jonsen, 1988; Watt, 2016). However, in some circumstances, the principle of respect for the pregnant woman's autonomy may collide with the principles of beneficence and/or non-maleficence toward the foetus. Once again, principles are difficult to reconcile, and it is essential to avoid the risk of fulfilling a moral obligation of beneficence towards the foetus at the expense of maternal autonomy. Our personal view is that alleged foetal rights cannot be elevated over the rights of the pregnant woman and that the woman's autonomy and right to self-determination should override the ‘rights’ and interests of her foetus, provided she is fully and adequately informed and competent to make a decision.

Methods

Literature searches were conducted on relevant demographic, social science and medical science databases (SocINDEX, Econlit, PopLine, Medline, Embase and Current Contents) and via other sources. Searches focused on subjects related to bioethical and legal controversies in the field of PGD and PD, wrongful birth and wrongful life. A review of the international state of law was carried out, focusing attention on the peculiar issue of wrongful life and investigating the different jurisdictional solutions of wrongful life and birth claims in a comparative survey.

PGD: bioethical considerations

The constant evolution of scientific progress has permitted us to exceed the boundaries of what was once considered the natural cycle of life, posing several ethical dilemmas that are not easy to solve (Kushnir et al., 2016). Intervening actively, by planning and deciding the phases linked to procreation and birth, is nowadays possible (Dondorp and de Wert, 2011; Hens et al., 2013; Harper et al., 2014). These are complex times in which the rights of the couple are intertwined with the rights of the foetus, with the interests of each connected in various ways to planned parenthood and ultimately to the attainment of life, but only on certain conditions. The legitimate expectations of becoming parents are balanced against the greater or lesser protection, often unsuccessful, of an entity that is not yet a person. The ethical and legal debate is intense and in continuous evolution, and in tension with the attribution of individual control and widespread acknowledgement of the principle of self-determination.

Procreation and birth introduce responsibilities that were once not even imaginable, obliging the judge and the ethicist to modify their attitudes to, if not life itself, at least the quality of life. With prenatal screening and even more so, preimplantation diagnosis, the decision, to become parents no matter what or instead to subordinate this desire to the birth of a healthy child, is left to the parents themselves. In the absence of well-defined legislation, which would be the preferable option, it is important to at least reach, if possible, a shared ethical decision with a scale of values that can guide the lawfulness of choices (Dondorp and van Lith, 2015; Lowther et al., 2015; Wasserman, 2015).

The suffering and hardships that a disabled life entails can be rejected by preventing the birth event itself. They could also be alleviated through compensation, thus attributing the responsibility to others. But who is able to evaluate the quality of life of someone born with a disability? And therefore, who can legitimately initiate legal proceedings in order to obtain relief? These are just some of the many questions raised by the issue of prenatal and preimplantation diagnosis.

In today's society, there is a widespread feeling that it is not life that should be protected at all costs, but the quality of life. This view would seem to be in direct opposition to the concept of the ‘sanctity of life’. Consequently, the approach to such a delicate issue cannot disregard the sensitivity underlying those ethical values which should serve as coordinates. These issues have been the matter of a lively doctrinal, regulatory and juridical debate all over the world (Molinelli et al., 2012; Propping and Schott, 2014; Brezina and Kutteh, 2015; de Jong and de Wert, 2015).

The possibility of carrying out PGD for couples who have resorted to assisted reproduction has been a matter of debate in several countries (Boggio and Corbellini, 2009). This practice consists in the collection of cell samples from the embryo before its implantation in the mother's womb in order to verify its state of health and, above all, the presence of any genetic disorders (Gulino et al., 2013; Zuradzki, 2014; Durland, 2015; Hu et al., 2015; Capalbo et al. 2016; Chang et al. 2016; Irion and Irion, 2016). In several countries, including Italy, the right to preimplantation diagnosis, for couples who had resorted to in vitro fertilization techniques, was not recognized from the start (Turillazzi and Fineschi, 2008; Busardò et al., 2014; Turillazzi et al., 2015). In several cases, besides the prohibition of any kind of preimplantation diagnosis for eugenic purposes, it has been stressed that any investigations carried out should be ‘observational’. This, then, rules out invasive studies, such as those that involve the collection of cell samples.

Such positions have fuelled the debate, in particular, on the balancing of interests between the protection of the embryo on the one hand and, on the other, the protection of the mother's health and the couple's right to know the state of health of the embryo itself. In particular, it may be debatable to prohibit the assessment of possible anomalies or genetic disorders through an investigation of the embryo which is not yet implanted in the womb while legalizing the PD of the foetus. The latter procedure is clearly more aggressive than preimplantation genetic diagnosis and may lead to the termination of pregnancy, which may be both physically painful and mentally distressing for the mother.

Recently, however, there has been a tendency to recognize the parents’ right to access preimplantation diagnosis techniques.

Among the most important arguments raised in this respect, it is worth mentioning: (i) the parents’ right to be informed as to the state of health of the embryo to be implanted, in accordance with the general principle of informed consent required for all medical treatment; (ii) the necessity to protect the mother's right to health since the implantation of a malformed embryo or of one carrying genetic disorders cannot only cause psychological distress to the mother but could also increase the risk of pregnancy complications or miscarriage; and (iii) the problematic nature of the ban on PGD, in view of the mother's right to carry out genetic analysis and diagnosis on the already formed foetus (through the amniocentesis and chorionic villus sampling techniques) and subsequently to interrupt pregnancy.

Undoubtedly, the application of PGD raises controversial and highly debated ethical problems (Robertson, 2003, 2005; De Wert, 2005; Soini et al., 2006; Basille et al., 2009; Hens et al., 2013; De Wert, et al., 2014; Whetstine, 2015). Aside from the moral status of the embryo, debates concerning the acceptability of PGD have included the potential biological impact as well as moral, political and religious values. It should be borne in mind that ethical concerns relating to PGD are strictly intertwined with religious values and beliefs, cultural and social backgrounds, and lived experience and emotions (Gebhart et al., 2016). As in other fields of predictive prenatal medicine, heterogeneous positions may exist, depending on whether a human being, defined as a person, is considered as coming into existence at the time of fertilization or as gradually acquiring the full status of a human being during intrauterine development.

In this regard, similarities and differences can be drawn with regard to PD. For those who believe that the foetus is not a person, there seem to be differences in the ethical justification between the two procedures, PGD and PD. PGD may be psychologically less distressing for the mother and the couple who may feel more detached from an embryo on a Petri dish compared to a foetus growing inside the womb. In the same way, for those who attribute moral status to the embryo, both PGD and PD are unacceptable. With this hypothesis, there are also slight differences between the two procedures: one might argue, for example that in PGD the ethical disvalue can be greater because more embryos are created, by assisted procreation methods, and then destroyed while, in general, in PD followed by an abortion, only one foetus is aborted. Yet again, since a moral value can be attributed to pregnancy itself, some might consider PGD to be ethically more acceptable than PD since, in the former, the pregnancy has not yet begun (Cameron and Williamson, 2003; Bartha et al., 2006).

It has been said that PGD is morally singular due to the fact that patients and clinicians are involved in creating a new life, which also entails responsibility for the welfare of the future child (Hens et al., 2013). PGD is a part of the complex debate surrounding ‘procreative beneficence’ that states that if selection of an embryo is reasonably possible, then couples have a moral obligation to select the embryo whose life can be expected to be the best quality (Savulescu, 2001, 2007; Savulescu and Kahane, 2009; Rodriguez-Purata et al., 2015). This concept in itself, has raised many ethical controversies (Bennett, 2014; Petersen, 2015). Furthermore, from the advantages of predictive medicine to the risk of genetic discrimination, choices may become more and more difficult and controversial (Aurenque, 2015; Mertes and Hens, 2015). From the standpoint of ethical speculation, there are many points of discussion. The ethical and moral acceptability of PGD, which has a specific burden (e.g. risk of eventual embryo loss and costs of the procedure), may depend on the benefit of avoiding the conception of an affected child. In other words, diagnosis and genetic selection in order to avoid serious and potentially fatal (or seriously disabling) genetically determined diseases (where there is a high risk of serious diseases) may sound ethically differently from PGD for mutations in genes that merely increase the risk (without a guarantee that the condition will develop later) of less severe conditions or cause a carrier status for recessive disorders, or for sex selection for indirect medical reasons (an application often considered ‘eugenic’) (de Wert et al., 2014; Altarescu et al., 2015). There may be general agreement on the acceptability of the so-called medical model of PGD (deWert, 2002; Steinbock, 2002), when it focuses on and is restricted to the diagnosis of (future) health problems, more precisely aberrations/mutations which (may) affect the health of the prospective child, but it still remains ethically troublesome (McMahan, 2005).

Worries about the possible negative effects of the use of PGD on disabled people do exist on the grounds that it is discriminatory, has pernicious effects on the lives of disabled people, and expresses a hurtful view of disability (Parens and Asch, 2003; Malek, 2010). Some claim that even preventing the birth of severely disabled children using PGD is morally unacceptable (Petersen, 2005), predicting that the use of PD technologies will lead to more injustice and greater discrimination against people with disabilities, negatively affecting our perception and care of children who are born disabled.

Concerns and worries about the consequences of PGD technologies may become even more exacerbated when applied for the selection of desirable non-medical traits unrelated to health, such as intelligence, height, hair or eye colour, beauty or athletic genotypes (so-called ‘designer babies’) or when applied for the possibility offered, and obtainable by means of PGD, of conceiving healthy children to save the life of another diseased child (El-Toukhy et al., 2011). Even more debatable are the exceptional requests by couples who themselves are affected by a genetic disease (deafness, dwarfism by achondroplasia) to perform PGD and select embryos carrying the same mutation for transfer to the uterus. The International Bioethics Committee of UNESCO considers such an approach to be unethical because it does not take into account the many lifelong and irreversible disadvantages that will burden the future person.

Prenatal diagnosis

PD is one of the areas of medicine to receive a great deal of attention in recent years, both in the scientific and bioethical fields (Strong, 2003; Chervenak and McCullough, 2011; Chadwick and Childs, 2012; Berceanu et al., 2014; de Jong et al., 2015; Dondorp and van Lith, 2015). Interest has been fuelled by surprising and constant progress in the field and by inherent bioethical problems. Increasingly accurate prenatal tests and investigations give parents powerful tools for gleaning information about their unborn offspring (Brezina and Kearns, 2014). However, scientific progress in this field undoubtedly raises ethical challenges (Sijmons et al., 2011).

Before discussing the peculiar issue of wrongful life that derives from PD development, it is necessary to try to define the bioethical presuppositions that underlie PD in general.

The term PD refers to techniques that allow the diagnosis of several diseases of the human embryo or foetus. Although PD potentially allows targeted diagnostic testing for the planning of the delivery, the counselling and education of the couples, and early postnatal interventions for newborns with congenital malformations (Lakhoo, 2012), it also often detects severe abnormalities where treatment is unavailable or unlikely to be successful, and where the death of the foetus or neonate is a likely outcome. One of the options available to mothers (and couples) when a severe or lethal disease is detected is the termination of the pregnancy (Menahem and Grimwade, 2003; Athanasiadis et al., 2009; Kose et al., 2015; Maxwell et al., 2015; Domröse et al., 2016; Gaille, 2016).

Thus, the central issue is related to the status of the human embryo or foetus. The first problem is to define the human embryo or foetus. It is beyond the scope of this article to provide a detailed discussion of the bioethical and philosophical debate that has developed in our society surrounding the actual beginning of human life, which has always been viewed differently by various individuals, groups, cultures and religions (Dunstan, 1984; Shea, 1985; Beller and Zlatnik, 1992, 1995; Drgonec, 1994; Shannon, 1997; Reuter, 2000; Kurjak and Tripalo, 2003; Schenker, 2008; Benagiano et al., 2011; Ventura-Juncá and Santos, 2011). A question in the ongoing multidisciplinary debate is whether the life of an embryo could be considered similar to that of a human being. If so, from conception onwards, the same protection allowed to every human is also due for the embryo. Other positions consider that respect for the human life is conditioned by the level of its development. Over the years, these different positions have animated a lively debate on issues such as abortion. In recent years, the issue has acquired a new dimension due to our growing capacity to make diagnoses at the beginning of life in ways that could not have been anticipated some decades ago. As has been argued, these technologies have redefined the scale, scope and the boundaries of medicine (Webster, 2002).

In this paradigm, the first step is to pay particular attention to the ‘therapeutic’ indications for PD. Questions arise, such as ‘is there a treatment that is reasonably expected to benefit the patient?’, ‘are there side adverse effects?’ and ‘are these negative effects tolerable in the light of the expected benefits?’. Motives behind PD may vary from the prevention, healing and/or alleviation of diseases to allowing people (mother/parents) to make procreative informed decisions in accordance with their own values and view of life. If only the former motive is accepted, PD should only be carried out when the foetus with the disease or abnormality could potentially benefit from the available therapeutic measures. In recent years, advances in prenatal screening and diagnosis mean that the majority of genetic diseases can be detected early in gestation (Beaudet, 2015). Early diagnosis provides the option of possible treatment. Surgical foetal interventions, and especially prenatal stem cell and gene therapy, have the potential to treat a broad range of congenital disorders (Loukogeorgakis and Flake, 2014; McClain and Flake, 2016). However, the clinical scenario varies from foetal treatment with a reasonable chances of success, to experimental foetal therapy with a low chance of success, thus raising profound ethical issues (Dickens and Cook, 2003; Chervenak and McCullough, 2007; Noble and Rodeck, 2008; Dickens and Cook, 2011; Ville, 2011; Chadwick and Childs, 2012; Munson, 1975; McMann et al., 2014).

When PD leads to prenatal treatment, which may involve invasive procedures, this may put the pregnant woman's health at risk. Furthermore, complications such as premature birth cannot be overlooked. This brings into question the appropriateness of carrying out risky procedures for the uncertain possibility of benefit to the foetus and the possible conflict between maternal and foetal health. In such circumstances, the pregnant woman is asked to make decisions about her own medical care that unavoidably involves the health, prognosis and even the possibility of survival of her unborn child. Women themselves might find it difficult to decide for or against treatment. As a consequence, underlying issues are at stake: the responsibility of healthcare providers towards the mother and foetus and the duty to give appropriate information and advice to pregnant women (Hunt et al., 2005). The pregnant woman should be given all the information regarding the potential benefit and risk to the foetus, and to her own health and fertility.

Summing up, the ethical debate surrounding PD, some conflicting key points may be drawn.

For those for whom the human embryo should be considered a living being from conception onwards, PD can be justified when the option exists for therapeutic action on the foetus. The right of parents to be informed of the health status of the foetus may be another point to eventually be counterbalanced with the best interests of the foetus. Parents have the right to be informed so as to be able to adjust their expectations for their child in the face of the child's medical prognosis. Accurate information about their child and their child's condition may be a critical step in the adaptation process that accompanies the birth of a disabled or chronically ill newborn. However, in such cases, there is also potential conflict between the autonomy of the mother to accept or refuse these treatments and the rights and interests of the foetus, as well as the question of the degree to which the mother's choices should be respected. Mothers are called on to act as ‘moral agents’ in relation to choices for the foetus (Noble and Rodeck, 2008). As a consequence, the mother also has the right to refuse treatment, irrespective of foetal viability borders (Deprest et al., 2011). In other words, if the status of person is assigned to the foetus, both the interest of the foetus and the mother should be considered, and the beneficence-based obligation to the foetus must be balanced with the beneficence-based and autonomy-based obligations to the mother.

An alternative way of looking at the issue is to consider that the aim of PD is to enable mothers and parents to make informed decisions regarding the possibility or risk of having a child with a congenital disorder, with the alternative being termination of pregnancy. Those who take the position that the human foetus before birth does not deserve absolute protection, will justify PD even when there is no therapy possible, and termination of pregnancy may be the only alternative to giving birth to a child with a congenital disease.

Wrongful birth: the conceptual paradigm

Advances in PD open the floodgates to allegations of liability for so-called ‘wrongful birth’ or ‘wrongful life’ (Roth, 2007; Pioro et al., 2008). For many years now, as the number of tests has expanded, so too has the number of lawsuits alleging negligence against the medical profession (Grady, 1992; Capen, 1995; Fisher and Witty, 2001).

Here we draw the distinguishing line between wrongful birth and wrongful life (Table I). The term ‘wrongful birth’ refers to claims for alleged negligence where an opportunity has been lost to parents to terminate a pregnancy. These claims are often related to undetected foetal abnormalities and involve a claim for damages by the parents of a child for, most importantly, the costs of bringing up the child. Other types of damages are non-pecuniary losses for both the mother and the father for interference with family life (Brantley, 1976; Botkin, 1988; Botkin and Mehlman, 1994; Whitney and Rosenbaum, 2011; Hassan et al., 2014).

Wrongful life versus wrongful birth actions.

| . | Wrongful life . | Wrongful birth . |

|---|---|---|

| Action | Claim brought by or on behalf of a child. | Claim brought by the parents. |

| Claims | The child has suffered from birth defects because the doctor is responsible for the undesired life. |

|

| Damages |

|

|

| References | Kearl (1983), Kelly (1991), Jackson (1995), Gillon (1998), Giesen (2012), Gur (2014). | Lenke and Nemes (1985), Jackson (1995), Sullivan (2000), Pioro et al. (2008), Hassan et al. (2014), Hensel (2005). |

| . | Wrongful life . | Wrongful birth . |

|---|---|---|

| Action | Claim brought by or on behalf of a child. | Claim brought by the parents. |

| Claims | The child has suffered from birth defects because the doctor is responsible for the undesired life. |

|

| Damages |

|

|

| References | Kearl (1983), Kelly (1991), Jackson (1995), Gillon (1998), Giesen (2012), Gur (2014). | Lenke and Nemes (1985), Jackson (1995), Sullivan (2000), Pioro et al. (2008), Hassan et al. (2014), Hensel (2005). |

Wrongful life versus wrongful birth actions.

| . | Wrongful life . | Wrongful birth . |

|---|---|---|

| Action | Claim brought by or on behalf of a child. | Claim brought by the parents. |

| Claims | The child has suffered from birth defects because the doctor is responsible for the undesired life. |

|

| Damages |

|

|

| References | Kearl (1983), Kelly (1991), Jackson (1995), Gillon (1998), Giesen (2012), Gur (2014). | Lenke and Nemes (1985), Jackson (1995), Sullivan (2000), Pioro et al. (2008), Hassan et al. (2014), Hensel (2005). |

| . | Wrongful life . | Wrongful birth . |

|---|---|---|

| Action | Claim brought by or on behalf of a child. | Claim brought by the parents. |

| Claims | The child has suffered from birth defects because the doctor is responsible for the undesired life. |

|

| Damages |

|

|

| References | Kearl (1983), Kelly (1991), Jackson (1995), Gillon (1998), Giesen (2012), Gur (2014). | Lenke and Nemes (1985), Jackson (1995), Sullivan (2000), Pioro et al. (2008), Hassan et al. (2014), Hensel (2005). |

The topic of wrongful birth bears witness to the increasing value of information in doctor–patient relationships. This is supported by the copious scholarly literature which has, over time, shaped the contents, methods, times and sequences of information that should be given to patients within this relationship (Turillazzi et al., 2014). A lack of information has thus become a legal question which affords ample scope for claims by patients unable to exercise their right to an informed acceptance (or indeed, refusal) of treatment (Akazaki, 1999).

The role of information may become particularly complex, as in this case, when the decision of the patient (the mother) affects others (the unborn or newborn child, father and siblings), including the physician whose conduct has conditioned such a decision. These are cases where a lack of, or wrong, information regarding the malformation or chromosomic anomalies of the foetus, has denied the pregnant mother the right to exercise the ‘faculty’ of interrupting the pregnancy, thus resulting in the birth of an ‘unhealthy’ child (Frati et al., 2014). For this reason, the professional relationship should be directed both towards checking for foetal malformations and (in the event of a positive result) exercising the right to interrupt the pregnancy.

The conceptual paradigm, therefore, builds on the fact that the woman has made it clear that she desires a ‘healthy child’ (at the risk of interrupting the pregnancy) and therefore, the doctor's role is to suggest (and explain) all the possibilities for ‘safely’ determining the conditions of the foetus (Dimopoulos and Bagaric, 2003). The doctor is obliged, in such cases, to provide complete information regarding (all) possible diagnostic tests, including their level of invasiveness and risk, as well as the percentage of false negatives offered by the test chosen. Further tests should be proposed (but certainly not carried out routinely) as a possible alternative, outlining the risks they carry, so as to allow the pregnant mother to decide what is best for her pregnancy.

Wrongful birth claims: looking for the international roadmap

Wrongful birth claims are brought by the parents of a child born with severe defects against a physician whose alleged negligence in the PD deprived the parents of the opportunity to take an informed decision about whether to avoid or terminate the pregnancy.

Over the years there have been different kinds of situations that have been indented in this type of litigation: cases in which, due to negligent conduct, a foetal anomaly that would have led the mother to have an abortion was not diagnosed (Virginia Supreme Court; Naccash v. Burger, 1982); cases where an abortion in a woman with special risks was not achieved (Pennsylvania Supreme Court; Speck v. Finegold, 1981); and cases of sterilization procedures not properly handled by negligence (Court for the District of Columbia; Hartke v. McKelway, 1981; Jha, 2016).

Historical references to the evolution of this particular kind of damage are required in order to better understand the meaning of this particular request for compensation and damages, as well as the difference with the damage from ‘wrongful life’ and why in most cases the requests from wrongful birth are accepted while those from wrongful life are rejected.

In the United States, in the 1970s, wrongful birth actions were meant to be those actions made by the couple when an unintended birth occurred; these claims were addressed to the manufacturers of contraceptive methods, and against doctors who had administered ineffective drugs or had not carried out a proper sterilization. As a matter of fact, in that period, the evolution of contraceptive techniques, such as sterilization and birth control pills, began to allow birth control on the part of couples, raising the need for a real ‘family planning’. The claims for compensation were primarily targeted to reparation for the medical expenses related to pregnancy and childbirth, the pain and suffering, as well as the costs for the growth and education of the child (Court for the Southern District of West Virginia; Whittington v. Eli Lilly, 1971).

With the development of non-therapeutic abortion laws and genetic diagnosis, an evolution of case law concerning the ‘wrongful birth’ has arisen on the basis of the growing importance of the woman self-determination principle, since she is the holder of the right to abortion in the presence of foetal malformations. The evolution of genetic diagnostics has allowed doctors to promptly recognize, even in early pregnancy, the presence of certain foetal malformations and has inevitably resulted in an increase in legal actions related to the use of such techniques, expanding the types of damage required. This obliged the doctors to offer the proper genetic testing, to correctly interpret the results and to inform parents promptly (DuBois, 2001; Carey, 2005). Therefore, due to these developments in science and jurisprudence, also the damage from ‘wrongful birth’ has evolved; as a matter of fact it is invoked by parents following the birth of an unwanted child because of his/her disability, in cases where the mother is deprived of the opportunity to decide whether to terminate the pregnancy (Moore, 1979).

The first wrongful birth claim presented at the Law Courts was in 1934, in the State of Minnesota, United States. In the specific case, Christensen v. Thornby, the Minnesota Supreme Court rejected the request of parents, decreeing that the birth of a new child was a blessed event.

A few decades later, an important jurisprudential current had been established. A first acknowledgement of wrongful birth damage was implemented by the Court of Texas in 1975, in the case Jacobs v. Theimer, 519 S.W.2d 846 (Tex. 1975). The case concerned a claim made by the parents of a child born with defects as a result of the contraction of rubella by the mother during the first month of pregnancy. Negligent conduct consisting of an incorrect diagnosis that had prevented the parent from terminating the pregnancy was contested to the clinicians. The Texas Supreme Court recognized, in this case, the damage caused by compensating the costs involved in the care and treatment of the child born with disabilities, but not the pain and emotional distress suffered by parents. In support of the acceptance of the compensation request, was the lack of information from physicians because the treatment or negligent advice had deprived the parents of the possibility to terminate the pregnancy.

The differences between the different types of damage that may be required as a result of wrongful birth and wrongful life were well established in 1996 by the Court of South Africa in the case of Friedman v. Glicksman: the wrongful birth damage regards the damages claimed by parents who would choose to terminate the pregnancy if properly informed of foetal defects/malformations, while the damage from wrongful life concerns the damages claimed by the child on the grounds that the lack of information about the malformation prevented parents from terminating the pregnancy, causing the birth of a child with disabilities, resulting in pain and suffering for the life of a ‘born malformed’ (Court of South Africa; Friedman v. Glicksman, 1996).

Nowadays, courts around the word generally allow wrongful birth actions.

In USA, the majority of States allow actions of wrongful birth: Alabama, Alaska, California, Colorado, Connecticut, Delaware, Florida, Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Louisiana, Maryland, Massachusetts, Nevada, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, Rhode Island, Tennessee, Texas, Virginia, Washington, West Virginia, Wyoming (Maryland Court of Special Appeals, 2001). The words of the Supreme Court of New Hampshire sum up the case law of the American States that recognize the wrongful birth actions: ‘a wrongful birth claim is unlike any other medical malpractice action because it involves the uniquely personal choice to terminate a pregnancy or give birth to a child with the increased possibility of severe birth defects'. In this respect, a fact finder should also consider the plaintiff's emotional and physical ability to digest and act upon the information concerning the increased possibility of birth defects within the time period at issue, as well as her willingness and ability to travel to another jurisdiction to obtain an abortion during her third trimester, had she been able to arrange one (Supreme Court of New Hampshire; Hall v. Dartmouth Hitchcock Medical Center, 2006). In a more recent judgement of 2011, the Court of Illinois (Court of Illinois; Clark v. Children's Memorial Hospital, 2011) affirmed these principles and, furthermore, the compensable damage was recognized not only for the cost of the care of the disabled child (up to the 18th birthday) but also for the moral suffering (Hurley and McKenna, 2013). In a minority of states, however, the damage from wrongful birth is not recognized; in Liddington v. Burns (U.S. District Court for the Western District of Oklahoma, 1995), the Court of Oklahoma rejected the claim for two reasons: the first reason concerned the ultrasound test, as the result was not recognized as eligible to justify an abortion, and secondly, the Court rejected the request arguing that there was no indisputable evidence that the mother would have wanted and would have had an abortion in the first trimester of pregnancy. Furthermore, in some states, there is a specific article in the statues specifying that wrongful birth and/or wrongful life claims are banned: Kansas (K.S.A. 60-1906, 2013), South Dakota (SDCL 21-55-2, 1987), Oklahoma (63 Okl.St.Ann. 1-741.12, 2010), Missouri (V.A.M.S. 188.130, 1986), Michigan (M.C.L.A. 600.2971, 2011), Minnesota (M.S.A. 145.424, 2005), Maine (24 M.R.S.A. 2931,1990), Idaho (I.C. 5-334, 2010) and Arizona (A.R.S. 12-719, 2012) (Eagan, 2006; Pergament and Ilijic, 2014).

The Supreme Court of Canada, in Arndt v. Smith (2 S.C.R. 539, 1997) recognized ‘wrongful birth’ damage, justifying the decision with an interference with the right to choose an abortion. In this case, Carol Arndt sued her physician for not informing her of the risks associated with the contraction of chickenpox during pregnancy. During the dispute, the mother argued that, if properly informed about the risk of harm to the foetus, she would have terminated the pregnancy; on the other hand, the doctor contested that the patient would have still carried the pregnancy to term and that therefore he could not be attributed any responsibility (Rinaldi, 2009).

In the United Kingdom, in the 2000s, courts recognized substantial amounts including the expenses for the growth of a child born malformed, for loss of earnings and for the school. The leading case for such claims was the case of Parkinson v. St James e Seacroft Hospital NHS Trust (QB 266, 2002). On this occasion, the Court ordered the payment of damages caused by the birth of a disabled child due to a sterilization. A similar decision was adopted in the case of Rand v. East Dorset Health Authority (2000) Lloyd's Rep Med, in which the parents were not informed about the result of a test that showed that the mother was likely to give birth to a baby suffering from Down syndrome. The court held that the parents were entitled to claim compensation for damages related to the child support costs since they had not been able to exercise their right to terminate the pregnancy (Hassan et al., 2014). In 2002, in Rees v. Darlington Memorial Hospital NHS Trust Ltd., the Court of Appeal ruled that the birth of a healthy but unplanned child brings additional costs; moreover, the judge stated that the mother has the right to claim compensation for damage caused by a birth due to a negligent conduct of the doctor (London Royal Courts of Justice; Rees v. Darlington Memorial Hospital NHS Trust, 2003).

In Australia, the case law is very similar to that in the United Kingdom, as demonstrated by the case Cattanach v. Melchior, discussed by the High Court in 2003. In particular, most of the appeals have been received with recognition of the damage resulting from the loss of earnings and expenses for the maintenance of the child (Thomas, 2002). Moreover, in the case of Veivers v. Connolly 2 Qd R 326 on 1995, the Supreme Court of Queensland ruled in favour of a mother who had given birth to a child with severe disabilities due to negligent conduct of the doctor who failed to diagnose the mother with rubella and to inform her about the consequent risks for the foetus (Petersen, 1997).

In Ireland, the Constitutional right to life has a weighty impact on the effect of wrongful birth and life cases, as this right is extensively protected by the judiciary. In this regard, the most recent case law perceives the unborn child, whether healthy or disabled, as a blessing, resulting in rejection of the claims for compensation for damage caused by wrongful conception or wrongful birth cases (Alvarez, 2000). The fact that the child is a blessing and that he/she is very much wanted by the society in Ireland is evident within the provisions of the Constitution of Ireland 1937 as amended. In fact, the article 40.3.3 declares that ‘The State acknowledges the right to life of the unborn and, with due regard to the equal right to life of the mother, guarantees in its laws to respect, and, as far as practicable, by its laws to defend and vindicate that right.’ (Daly, 2005).

In the Netherlands, wrongful birth claims have been approved for many years; in 1997, with the particular so-called Missing IUD case, the Dutch Supreme Court (the Hoge Raad) recognized the compensation of the costs for the growth of the child as well as for non-economic damages in favour of the mother. Moreover, in a more recent judgement of 26 March 2003, the Court extensively clarified that this type of damage is to be recognized to parents. In this case, a foetal abnormality was not promptly recognized and the child was born with multiple malformations, both mental and physical. This negligence of the doctor resulted in violating the legal right of the mother to opt for an abortion. Therefore, damages against the hospital, amounting to the baby care costs, were also awarded to the parents (Nys and Dute, 2004).

In Germany, the German Supreme Court allowed wrongful birth claims in 1980 with two cases: the 76 BGHZ 249 and the 76 BGHZ 259; moreover, in the judgement of Bundesgerichtshof on 1983 the ‘wrongful birth’ claim was allowed because a disabled child was born as a consequence of a wrong diagnosis by the doctor; the compensation was recognized on the grounds of a negligent non-performance of contract (Dutch Federal Court of Justice, 1983; Carmi and Wax, 2002; Shaw, 1990). In recent years, the situation was rather difficult when it came to maintenance loss (non-pecuniary losses are awarded for the mother). This issue is still a matter of extensive debate; in fact, the German Federal Court of Justice is in favour of allowing a wrongful birth claim, awarding the costs of raising the child under certain conditions, but the Second Chamber of the constitutional court, the Federal Constitutional Court, is against this, considering these damages to be contrary to the dignity of the child. The Federal Court of Justice has remained true to its opinion, however, and these costs are generally compensated (van Gerven et al., 2001; Giesen, 2008).

The Austrian Supreme Court on 12 July 1990 (Juristische Blatter, 1991) applied the theory of informed consent and wrongful birth. In the decision at issue, the judges came to the conclusion that a physician does not need to inform about every single risk of medical therapy. With regard to wrongful birth, the court rejected the maintenance costs which were caused by a physician's negligent conduct because the doctor is not responsible for an unwanted pregnancy on the basis of informed consent (Bernat, 1992).

In Italy, the debate on the recognition of wrongful birth and wrongful life damages has been going for years. With the judgement no. 25767 on 22 December 2015, the Highest Italian Court provided a clear jurisprudence recognizing wrongful birth claims and rejecting wrongful life ones. The Court found that the inability of the woman to choose to terminate the pregnancy because of the negligence of the doctor, who had not properly informed her, is a source of civil liability; the request for damages made by the parents should, therefore, be accepted.

In Spain, wrongful birth claims are allowed but only if they are brought by the mother. The Supreme Court was clear on this matter, ruling that the right to opt for abortion constitutes a personal, non-transferable, right of the mother, which becomes an obstacle to a claim made exclusively by the father. The sentence of the Supreme Court of the 5 December 2007 had clarified the reasons stating that the abortion is a practice exclusively inherent to women. Concluding, solely the mother is entitled to claim compensation for wrongful birth damage, being the only holder of the right to abortion (Arantzazu Vicandi Martínez, 2013).

In Belgium, the Brussels Court of Appeal ruled that parents may sue physicians who fail to diagnose serious foetal malformations, assuming that parents, if properly informed, would proceed to the interruption of pregnancy. In particular, with the statement of the 21 September 2010, the Brussels Court of Appeal dealt with the case of a Muslim woman who complained that the hospital did not warn her of the serious illness affecting her foetus. The hospital justified the information defect arguing that the disease was found after the deadline prescribed by Islam for abortion. The Court, accepting the claim, concluded that the compensation must be accorded because the lack of information determined the birth of a child with disabilities (Court of Appeal of Brussels, 2010).

In France, the 4 March 2002 law stated that nobody can claim a damage resulting from the mere fact of being born, which leaves open a wide range of interpretations. In principle, a claim for child maintenance costs is deemed possible in cases of birth of a malformed child (in this occurrence, the non-pecuniary damage is also recognized) or in cases where the mother is in poor financial condition or develops mental problems after the baby is born. The birth of a healthy child is not considered a sufficient ground to justify the claim for damages (Viney and Jourdain, 2006).

In May 2011, the European Court of Human Rights ruled on wrongful birth. In the case R. R. v. Poland, a woman claimed that her access to prenatal genetic testing had been denied with the subsequent birth of a child suffering from Turner syndrome. The Court highlighted a violation regarding the prohibition of inhuman or degrading treatment and a violation of the right to respect for private and family life, thereby deciding in favour of the mother. In the judgement, it was also noted that the failure of the prenatal genetic test had violated the woman's right to health-related information and the right to personal autonomy.

In Japan, the claims for damages due to wrongful birth are generally accepted. The legal basis of this approach lies in the violation of the doctor's duty to give advice about the probability of the birth of a child with disabilities. In fact, the Japanese system does not provide foetal indications for abortion (Sakaihara, 2002).

In New Zealand, on the basis of the current legislation, there is no legal ability for either the parents or the child to obtain compensation for negligent prenatal genetic testing, even though the debate is still open. In this regard, the New Zealand Supreme Court recently ruled on the case Allenby v. H., considering that the law provides a coverage for pregnancies arising from medical misadventures (Tobin, 2005; Gordon, 2012; Cleary, 2013).

South African law recognizes claims for wrongful pregnancy and wrongful birth. The first case involving wrongful birth in a South African court was in 1996, in the matter of Friedman v. Glicksman; on that occasion, the mother of a child born with disabilities had accused the doctor because, if properly informed, she would have terminated the pregnancy. In its decision, the court upheld the appeal due to a breach of the contractual duty of the physician to properly inform the mother about the congenital deficits of her child (Strauss, 1996).

In Israel, actions for wrongful birth are allowed: in a recent sentence, on May 2012, Israeli Supreme Court declared that while wrongful birth claims were still permitted, wrongful life claims were no longer accepted in a court of law. Thus, the parents are entitled to compensation for the additional expenses required to fulfil their child's medical needs and support the child. In cases where the child continues to depend on the parents beyond childhood because of his/her disability, compensation is provided for the expenses resulting from the child's maintenance for the duration of his life (Mor, 2014).

In other countries, such as in Estonia, there is no a specific legislation and the debate is still open (Sõritsa and Lahe, 2014).

In the Czech Republic, the Brno Regional Court (judgement file No. 24 Co 66/2001) ordered an hospital to compensate the non-pecuniary damage suffered by a mother who had given birth to a healthy baby, despite her manifest desire to have an abortion. Emphasizing the right of the mother to decide about her unborn child, the High Court in Olomouc upheld the Regional Court decision in its decision on No. 1 Co 192/2008.

In Chile, a ‘wrongful birth’ claim is not admissible because in Chilean legislation abortions are always forbidden by law.

This review of the international case law shows that the majority of states recognize the wrongful birth claims.

In fact, in case of negligent conduct consisting on the breach of the doctor's duty to provide information about the presence of foetal malformations, the courts recognize the liability for violation of the right to self-determination of women, according to the principles of modern medical practice.

The foreclosure of the opportunity to make an informed choice about the interruption of pregnancy, resulting from the lack of information about the risk of giving birth to a child with disabilities, makes the physician responsible for damages resulting from an unwanted birth which is therefore deserving of a compensation claim.

Wrongful life

Claims of ‘wrongful life’ are made on behalf of the disabled child by his/her representatives, i.e. most notably the parents (Schmidt, 1983; Tucker, 1988–1989; Bottis, 2004). These claims, for having to live a life full of suffering because of a disability, are brought against a doctor or obstetrician. In these cases, the claim is that, overall, living is considered to bring more harm than good.

Although wrongful life is a highly debated topic (Liu, 1987; Sharman, 2001; Perry, 2007; DeGrazia, 2015; Francis, 2015), wrongful life claims have been brought against medical practitioners in many developed countries. Wrongful life cases are usually controversial and verdicts may differ between countries based on differences in the various legal jurisdictions (Giesen, 2012).

Wrongful life claims: an international overview

The term ‘wrongful life’ was first used in a case of illegitimate birth in the United States (Supreme Court of Illinois; Zepeda v. Zepeda, 1963).

The child claimed damages from his father for being an illegitimate child and suffering all the consequent hardships. The Illinois Supreme Court dismissed the case, focusing on the fact that the acceptance of a wrongful life claim would have legal and social implications and might encourage people to seek damages for any conditions they considered disadvantageous (Evgenia, 2012).

Nowadays, courts around the world are generally reluctant to acknowledge such claims due to their ethical and legal implications.

In the Netherlands, the Supreme Court recognized a wrongful life claim in the Kelly Molenaar case in March 2005. The Court granted living costs to a child born with a congenital malformation, i.e. for her upbringing, greater costs related to her disability and non-pecuniary losses for harmful individual experiences. Although it was affirmed that a life with a disability has no less value than a healthy life, it was acknowledged that the child's life would be more difficult (Nys and Dute, 2004; Sheldon, 2003, 2005). The Dutch legislators have not subsequently intervened on the matter, not even when asked specifically to consider doing so, affirming that the decision of the Supreme Court was in accordance with the rules of private law in the Netherlands and that there was no apparent reason for the legislator to decide otherwise on this issue (Giesen, 2012).

In Spain, wrongful life actions were first excluded and then indirectly allowed. The first time dates back to 1997 when the Supreme Court rejected a request, affirming that it was in clear contrast with the right to life and human dignity. Later, on 4 February 1998, 6 July 2007 and 4 November 2008, the Supreme Court confirmed its prior judgement, affirming that the birth of a diseased person is not an evil and that the birth of a child cannot be considered a damage. More recently, on 16 June 2010 and even prior to this, on 18 December 2003, the Supreme Court indirectly allowed wrongful life actions. Although it was denied that the birth of a child could be considered a damage, a baby born with a disability was awarded a lifelong monthly pension, inspired by social welfare principles (de Angel Yágüez, 2005).

In Germany, wrongful life actions are denied. The principal case concerns a child whose mother contracted rubella during pregnancy (BGH Bundesgerichtshof, 18 January 1983). The mother had not been informed about the risks of giving birth to a disabled child and, as legal guardian, she brought wrongful birth and wrongful life proceedings to ask for compensation on the child's behalf. The German judges recognized the validity of the mother's action while rejecting the wrongful life case, on the grounds that doctors do not have the obligation to impede the birth of a baby with congenital malformations, as to do so would be to undermine the value of human life itself (Giesen, 1988; Markesinis and Unberath, 2002).

Austria excludes wrongful life actions. The principal case is the Supreme Court's decision on 25 May 1999. According to the judge, the obligation of abortion in the event of a diagnosis of malformation does not exist in the Austrian judicial system; therefore, there was no causal relationship between the omitted diagnosis and the birth. The Austrian judges have considered unquantifiable the wrongful life damage and inadmissible the possibility for the child born with disabilities to bring proceedings even against his or her parents (Bernat, 1992).

In the United Kingdom, wrongful life claims are not recognized. Although the 1976 Congenital Disabilities Act allows the child to sue the doctor whose conduct was responsible for his or her disability, this possibility does not exist in the case of omitted information. In the famous 1982 McKay v. Essex Area Health Authority case, the legitimacy of wrongful life actions was categorically excluded (Queen's Bench, 1982). This is a landmark case for other common law courts. An erroneous diagnosis had led to the birth of a baby suffering from a severe disability, because of rubella contracted during the gestation period. The judges rejected the parents’ claim. There was conflict with the principle of the sanctity of human life, according to which all human life is of value and it is therefore inconceivable that the life of a disabled person is considered of lesser value than a healthy one. For the English judges, it was important to prevent the further risk of children born with disabilities bringing proceedings even against their own parents and pushing doctors towards defensive medicine, such as suggesting abortion in the case of foetal malformation diagnosis. In general, for the doctor, the duty of abortion does not exist; therefore there is no causal relationship between omission and birth. Such disability is congenital and cannot be attributed in any way to medical conduct (Jackson, 1996; Gur, 2014).

In France, wrongful life actions are not allowed but the debate on the topic became very interesting around 2000. In 1994, magistrates faced this issue for the first time with the Quarez case. The judges denied compensation to a child born with a disability because the maintenance costs were absorbed by the proceeding brought by his parents. The principal French case is the Perruche case (Cour de Cassation de France, 2000), in which a boy was born with a severe disability because of rubella contracted during pregnancy. In this case, the Supreme Court admitted the wrongful life action, recognizing the causal connection between the doctor's omission and the undesired birth (Dorozynski, 2001). This sentence provoked strong reaction from the public who judged that the decision infringed the right to life and human dignity. Despite this, a few months later, the Supreme Court pronounced up to five judgements between 13 July and 28 November 2001. Law no. 303 of 4 March 2002 embraced public opinion and excluded wrongful life actions, unless the disability was caused by medical conduct. The political choice was clear, i.e. to avoid qualifying life as compensable and passing on this charge to the medical profession. The French case is even more interesting because the legislator deemed the law to be retroactive, thus provoking the intervention of the European Court of Human Rights. Although the European Court recognized the legitimacy of the content of the legislation, it condemned the fact that it was retroactive (Loi Kouchner 2002; ECHR, Vo v. France, 2004; Clement and Rodat, 2006; Manaouil et al., 2012; Manaouil and Jardè, 2012).

A bill similar to the French one was proposed in Belgium in January 2002 but never became law. The court of first instance of Brussels has twice allowed a wrongful life claim under Belgian general tort law, citing the French Perruche case, and the Brussels’ Court of Appeal has recently (Court of Appeal of Brussels, 2010) also allowed a claim. The defendant has lodged an appeal at the Belgian Supreme Court. Currently in Belgium, wrongful life is still neither regulated nor clear (Giesen, 2012; Devisch, 2013).

In Italy, the position of judges in this regard were not entirely clear until a recent judgement of the Highest Court that seems to have finally closed the issue. Some judges used to recognize the right to compensation only for parents, while, recently, other judges have extended this right also to the child with congenital malformations. These disagreements led the Highest Italian Court to convene in a unifying resolution and to pronounce a judgement (no. 25767/22 December 2015) to be followed by all others Italian courts. Therefore, the right to compensation for wrongful life claims has definitely been excluded.

Also in Hungary, after an earlier acceptance of wrongful life claims, the Supreme Court (Unificatory Decision of no. 1/2008, 12 March 2008) established that wrongful life claims cannot be accepted under Hungarian law (Winiger et al., 2011). Greece, Poland and Portugal are also rejecting this kind of claim (Giesen, 2012). There is no case law for wrongful conception, wrongful birth and wrongful life in Estonia (Sõritsa and Lahe, 2014).

The state of Israel recognized wrongful life actions for more than twenty years. This changed in 2012 with the Hammer decision, interrupting a jurisprudential line that went as far back as 1986 with the Zeitsov v. Katz case (Levi, 1987; Carmi, 1990). For the judges, the acknowledgement of the right to compensation aimed to improve the quality of a life that had begun with an inferior condition and was characterized by pain, since there were few socio-economic structures to help and assist disabled people. In May 2012, with the Hammer v. Amit case, the Israeli Supreme Court banned these actions, thereby refusing recognition of the right not to be born if not in good health (Israeli Supreme Court, 2012; Mor, 2014).

Canadian (Toews and Caulfield, 2014) and most American courts also deny this cause of action. The American States that allow wrongful life actions are the State of California with the Curlender v. Bioscience Laboratories case and the Turpin v. Sortini case, the State of Washington with the Haberson v. Parke-Davis case and the State of New Jersey with the Prokanic v. Cillo case (VanDerhoef, 1983). The Californian case is perhaps the most interesting one because it overturns a previous line that had excluded the legitimacy of such actions. The judges of Curlender v. Bioscience Laboratories case, rejecting the explanatory statements regarding the sanctity of life and the impossibility of measuring the difference between a life with deficiencies and the emptiness of non-existing adopted up to that moment, allowed wrongful life actions and the fact that a disabled person's life could be compensable. After 2 years, in 1982, with the Turpin v. Sortini case, the Californian judges allowed such actions, specifying, however, that they could be made only against doctors and not against parents, as this would restrict the latter's freedom of choice in the procreative domain. However, in contrast to the Curlender v. Bioscience Laboratories case, the judges restricted the compensation just to the major costs connected to disability. The other states are essentially in agreement with the Californian judges’ position (Laufer, 1982; Steinbock, 1986; Klein and Mahoney, 2007).

Although in Japan a child who is born disabled is able to file a claim against the person who injured him or her in the mother's womb (Sakaihara, 2007) and cases of wrongful birth claims have been awarded (Sakaihara, 2002), to the best of our knowledge no wrongful life lawsuits against medical practitioners have been filed in Japan.

In Australia, claims regarding both wrongful life and wrongful birth cases have been brought to the attention of the courts. In 2003 a High Court decision stated that damages may not only be awarded for pain and suffering and any loss of income due to the pregnancy and birth, but also for the costs of raising the child to 18 years of age. Following this decision, legislation was introduced in New South Wales, Queensland and South Australia preventing an award of damages for the costs of raising a child in ‘wrongful birth’ claims. In 2006 a decision of the High Court (High Court of Australia, 2006; New South Wales Court of Appeal, 2015) regarding a wrongful life claim established that disabled children are unable to sue medical practitioners for wrongful life, but the parents of disabled children are still able to pursue a claim in their own right for wrongful birth in the case of medical negligence (Devereux, 2002; Connors, 2005; Bird, 2006; Faunce and Jefferys, 2007).

Along the same lines are judgments of claims in Korea (Um, 2000) and in Singapore (Giesen, 2012).

Finally, the South African Supreme Court of Appeal, while assessing that healthcare practitioners who failed to detect and inform parents of congenital anomalies in the foetus so that they could have considered termination of pregnancy were liable to pay damages for wrongful birth, denied the wrongful life claim from the same child (South Africa Supreme Court of Appeal, 2008). The Court held that the law cannot adjudicate on the questions of existentialism, ‘which would require a court to determine whether a child should have been born, since this goes to the heart of what it is to be human’ (Chima and Mamdoo, 2015).

In conclusion, a glance at the international scenarios highlights the fact that the courts have overwhelmingly rejected wrongful life actions while at the same time approving those for wrongful birth (Tables II and III).

International state of law: wrongful Life allowed or not clear.

| States . | Cases . | Solutions . |

|---|---|---|

| Netherland | Kelly Molenaar, 2005 |

|

| USA: | ||

| (1) State of California | (1) Curlender v. Bio Lab; Turpin v. Sortini | A disabled person's life could be compensable. |

| (2) State of Washington | (2) Heberson v. Parke-Davis | In Turpin case, compensation was just for the major costs connected to disability. |

| (3) State of New Jersey | (3) Prokanic v. Cillo | |

| Belgium | Cour d'Appel Bruxelles, 21 Sept 2010, but the case is still in progress → The position of Belgium is actually not clear. | There is a causal relationship between the doctor's omissive practice and the undesired birth. |

| Spain | Tribunal Supremo, Jun 2010, rec. 448/2008 | Child would live a life with disability due to unwanted birth. The tools to limit the pain, suffering and distress were provided by a requirement to pay a monthly pension for life. → Wronguful Life action indirectly allowed. |

| Japan | No cases found | The position of Japan is not clear but a child who is born disabled is able to file a claim against the person who injured him or her in the mother's womb; cases of wrongful birth claims have been awarded. |

| States . | Cases . | Solutions . |

|---|---|---|

| Netherland | Kelly Molenaar, 2005 |

|

| USA: | ||

| (1) State of California | (1) Curlender v. Bio Lab; Turpin v. Sortini | A disabled person's life could be compensable. |

| (2) State of Washington | (2) Heberson v. Parke-Davis | In Turpin case, compensation was just for the major costs connected to disability. |

| (3) State of New Jersey | (3) Prokanic v. Cillo | |

| Belgium | Cour d'Appel Bruxelles, 21 Sept 2010, but the case is still in progress → The position of Belgium is actually not clear. | There is a causal relationship between the doctor's omissive practice and the undesired birth. |

| Spain | Tribunal Supremo, Jun 2010, rec. 448/2008 | Child would live a life with disability due to unwanted birth. The tools to limit the pain, suffering and distress were provided by a requirement to pay a monthly pension for life. → Wronguful Life action indirectly allowed. |

| Japan | No cases found | The position of Japan is not clear but a child who is born disabled is able to file a claim against the person who injured him or her in the mother's womb; cases of wrongful birth claims have been awarded. |

International state of law: wrongful Life allowed or not clear.

| States . | Cases . | Solutions . |

|---|---|---|

| Netherland | Kelly Molenaar, 2005 |

|

| USA: | ||

| (1) State of California | (1) Curlender v. Bio Lab; Turpin v. Sortini | A disabled person's life could be compensable. |

| (2) State of Washington | (2) Heberson v. Parke-Davis | In Turpin case, compensation was just for the major costs connected to disability. |

| (3) State of New Jersey | (3) Prokanic v. Cillo | |

| Belgium | Cour d'Appel Bruxelles, 21 Sept 2010, but the case is still in progress → The position of Belgium is actually not clear. | There is a causal relationship between the doctor's omissive practice and the undesired birth. |

| Spain | Tribunal Supremo, Jun 2010, rec. 448/2008 | Child would live a life with disability due to unwanted birth. The tools to limit the pain, suffering and distress were provided by a requirement to pay a monthly pension for life. → Wronguful Life action indirectly allowed. |

| Japan | No cases found | The position of Japan is not clear but a child who is born disabled is able to file a claim against the person who injured him or her in the mother's womb; cases of wrongful birth claims have been awarded. |

| States . | Cases . | Solutions . |

|---|---|---|

| Netherland | Kelly Molenaar, 2005 |

|

| USA: | ||

| (1) State of California | (1) Curlender v. Bio Lab; Turpin v. Sortini | A disabled person's life could be compensable. |

| (2) State of Washington | (2) Heberson v. Parke-Davis | In Turpin case, compensation was just for the major costs connected to disability. |

| (3) State of New Jersey | (3) Prokanic v. Cillo | |

| Belgium | Cour d'Appel Bruxelles, 21 Sept 2010, but the case is still in progress → The position of Belgium is actually not clear. | There is a causal relationship between the doctor's omissive practice and the undesired birth. |

| Spain | Tribunal Supremo, Jun 2010, rec. 448/2008 | Child would live a life with disability due to unwanted birth. The tools to limit the pain, suffering and distress were provided by a requirement to pay a monthly pension for life. → Wronguful Life action indirectly allowed. |

| Japan | No cases found | The position of Japan is not clear but a child who is born disabled is able to file a claim against the person who injured him or her in the mother's womb; cases of wrongful birth claims have been awarded. |

International state of law: wrongful life denied

| States . | Cases . | Solutions . |

|---|---|---|

| Italy | Italian Supreme Court, Joined Chambers, no. 25767 of 22 December 2015 |

|

| France | Law no. 303 of 4 March 2002 |

|

| Germany | BGH 18 Jan 1983 | The doctors do not have the obligation to prevent the birth of a malformed child. |

| Austria | OGH 25 May 1999 | Absence of causal relationship between the omiited diagnosis and the birth. |

| Hungary | Supreme Court, Unificatory Resolution, no. 1/2008 |

|

| United Kingdom | McKay v. Essex Area Health Authority, 1982 |

|

| Australia | Harriton v. Stephen and Waller v. Jans, 2006 |

|

| South Africa | Friedman v. Glicksman, 1996 and Stewart v.Botha, 2007 | The law cannot adjudicate on the questions of existentialism. |

| Israel | Hamer v. Amit, May 2012 |

|

| Canada | Bovington v. Hergott, 2008 |

|

| States . | Cases . | Solutions . |

|---|---|---|

| Italy | Italian Supreme Court, Joined Chambers, no. 25767 of 22 December 2015 |

|

| France | Law no. 303 of 4 March 2002 |

|

| Germany | BGH 18 Jan 1983 | The doctors do not have the obligation to prevent the birth of a malformed child. |

| Austria | OGH 25 May 1999 | Absence of causal relationship between the omiited diagnosis and the birth. |

| Hungary | Supreme Court, Unificatory Resolution, no. 1/2008 |

|

| United Kingdom | McKay v. Essex Area Health Authority, 1982 |

|

| Australia | Harriton v. Stephen and Waller v. Jans, 2006 |

|

| South Africa | Friedman v. Glicksman, 1996 and Stewart v.Botha, 2007 | The law cannot adjudicate on the questions of existentialism. |

| Israel | Hamer v. Amit, May 2012 |

|

| Canada | Bovington v. Hergott, 2008 |

|

International state of law: wrongful life denied

| States . | Cases . | Solutions . |

|---|---|---|

| Italy | Italian Supreme Court, Joined Chambers, no. 25767 of 22 December 2015 |

|

| France | Law no. 303 of 4 March 2002 |

|

| Germany | BGH 18 Jan 1983 | The doctors do not have the obligation to prevent the birth of a malformed child. |

| Austria | OGH 25 May 1999 | Absence of causal relationship between the omiited diagnosis and the birth. |

| Hungary | Supreme Court, Unificatory Resolution, no. 1/2008 |

|

| United Kingdom | McKay v. Essex Area Health Authority, 1982 |

|

| Australia | Harriton v. Stephen and Waller v. Jans, 2006 |

|

| South Africa | Friedman v. Glicksman, 1996 and Stewart v.Botha, 2007 | The law cannot adjudicate on the questions of existentialism. |

| Israel | Hamer v. Amit, May 2012 |

|

| Canada | Bovington v. Hergott, 2008 |

|

| States . | Cases . | Solutions . |

|---|---|---|

| Italy | Italian Supreme Court, Joined Chambers, no. 25767 of 22 December 2015 |

|

| France | Law no. 303 of 4 March 2002 |

|

| Germany | BGH 18 Jan 1983 | The doctors do not have the obligation to prevent the birth of a malformed child. |

| Austria | OGH 25 May 1999 | Absence of causal relationship between the omiited diagnosis and the birth. |

| Hungary | Supreme Court, Unificatory Resolution, no. 1/2008 |

|

| United Kingdom | McKay v. Essex Area Health Authority, 1982 |

|