Abstract

Research on the destinations of environmentally induced migrants has found simultaneous migration to both nearby and long-distance destinations, most likely caused by the comingling of evacuee and permanent migrant data. Using a unique data set of separate evacuee and migration destinations, we compare and contrast the pre-, peri-, and post-disaster migration systems of permanent migrants and temporary evacuees of the Great East Japan Earthquake and Tsunami. We construct and compare prefecture-to-prefecture migration matrices for Japanese prefectures to investigate the similarity of migration systems. We find evidence supporting the presence of two separate migration systems—one for evacuees, who seem to emphasize short distance migration, and one for more permanent migrants, who emphasize migration to destinations with preexisting ties. Additionally, our results show that permanent migration in the peri- and post-periods is largely identical to the preexisting migration system. Our results demonstrate stability in migration systems concerning migration after a major environmental event.

Similar content being viewed by others

Data Availability

All data and code necessary to reproduce the reported results are publicly available in a replication repository (https://osf.io/jvund/?view_only=3982ed9f1ea64c8cbb6c27b2683c9a79).

Notes

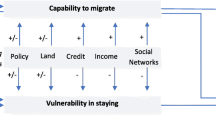

Findlay’s six principles are (1) most migrants want to stay in their current place of residence; (2) people tend to move over short distances rather than longer distances; (3) people do not always move to the most attractive destination but live/work nearer rather than farther; (4) attraction to destinations can be interpreted as increased income or returns to human capital; (5) destination selection is shaped by preexisting social and cultural connections; and (6) destinations can be viewed as attractive because of the social and cultural capital they offer.

References

Aoki, N. (2016). Adaptive governance for resilience in the wake of the 2011 Great East Japan Earthquake and Tsunami. Habitat International, 52, 20–25.

Black, R., Bennett, S. R. G., Thomas, S. M., & Beddington, J. R. (2011). Migration as adaptation. Nature, 478, 447–449.

Borts, G. H., & Stein, J. L. (1964). Economic growth in a free market. New York, NY: Columbia University Press.

Branigan, T. (2011, March 13). Earthquake and tsunami “Japan’s worst crisis since second world war.” The Guardian. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/world/2011/mar/13/japan-crisis-worst-since-second-world-war

Call, M. A., Gray, C., Yunus, M., & Emch, M. (2017). Disruption, not displacement: Environmental variability and temporary migration in Bangladesh. Global Environmental Change, 46, 157–165.

Crimella, C., & Dagnan, C.-S. (2011). The 11 March triple disaster in Japan. In F. Gemenne, P. Brücker, & D. Ionesco (Eds.), The state of environmental migration (pp. 35–46). Paris, France: Institut du développement durable et des relations internationales.

Curtis, K. J., Fussell, E., & DeWaard, J. (2015). Recovery migration after hurricanes Katrina and Rita: Spatial concentration and intensification in the migration system. Demography, 52, 1269–1293.

Curtis, K. J., & Schneider, A. (2011). Understanding the demographic implications of climate change: Estimates of localized population predictions under future scenarios of sea-level rise. Population and Environment, 33, 28–54.

Davis, K. F., Bhattachan, A., D’Odorico, P., & Suweis, S. (2018). A universal model for predicting human migration under climate change: Examining future sea level rise in Bangladesh. Environmental Research Letters, 13(6), 064030. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/aac4d4

DeWaard, J., Kim, K., & Raymer, J. (2012). Migration systems in Europe: Evidence from harmonized flow data. Demography, 49, 1307–1333.

Drost, H.-G. (2018). Philentropy: Similarity and distance quantification between probability functions (R package version 0.2.0) [Data set]. Retrieved from https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=philentropy

Fawcett, J. T. (1989). Networks, linkages, and migration systems. International Migration Review, 23, 671–680.

Feng, S., Krueger, A. B., & Oppenheimer, M. (2010). Linkages among climate change, crop yields and Mexico-US cross-border migration. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 107, 14257–14262.

Field, C. B., Barros, V. R., Dokken, D., Mach, K., Mastrandrea, M., Bilir, T., . . . White, L. L. (Eds.). (2014). Climate change 2014: Impacts, adaptation, and vulnerability. Part A: Global and sectoral aspects (Contribution of Working Group II to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. Retrieved from https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar5/wg2/

Findlay, A. M. (2011). Migrant destinations in an era of environmental change. Global Environmental Change, 21, S50–S58.

Frey, W., Singer, A., & Park, D. (2007). Resettling New Orleans: The first full picture from the census (Special Analysis in Metropolitan Policy). Washington, DC: Brookings Institution.

Fussell, E., Curtis, K. J., & DeWaard, J. (2014). Recovery migration to the city of New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina: A migration systems approach. Population and Environment, 35, 305–322.

Fussell, E., & Elliott, J. R. (2009). Introduction: Social organization of demographic responses to disaster: Studying population-environment interactions in the case of Hurricane Katrina. Organization & Environment, 22, 379–394.

Fussell, E., Sastry, N., & VanLandingham, M. (2010). Race, socioeconomic status, and return migration to New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina. Population and Environment, 31, 20–42.

Graves, P. E. (1980). Migration and climate. Journal of Regional Science, 20, 227–237.

Gray, C., & Bilsborrow, R. (2013). Environmental influences on human migration in rural Ecuador. Demography, 50, 1217–1241.

Gray, C., & Wise, E. (2016). Country-specific effects of climate variability on human migration. Climatic Change, 135, 555–568.

Groen, J., & Polivka, A. (2010). Going home after Hurricane Katrina: Determinants of return migration and changes in affected areas. Demography, 47, 821–844.

Gutmann, M. P., & Field, V. (2010). Katrina in historical context: Environment and migration in the U.S. Population and Environment, 31, 3–19.

Hasegawa, R. (2013). Disaster evacuation from Japan’s 2011 tsunami disaster and the Fukushima nuclear accident (Studies No. 05/13). Paris, France: Institut du developpement durable et des relations internationales.

Hassani-Mahmooei, B., & Parris, B. W. (2012). Climate change and internal migration patterns in Bangladesh: An agent-based model. Environment and Development Economics, 17, 763–780.

Hauer, M. E. (2017). Migration induced by sea-level rise could reshape the US population landscape. Nature Climate Change, 7, 321–325.

Haug, S. (2008). Migration networks and migration decision-making. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 34, 585–605.

Hellinger, E. (1909). Neue begründung der theorie quadratischer formen von unendlichvielen veränderlichen [New foundation of the theory of quadratic forms of infinite variables]. Journal für die reine und angewandte Mathematik, 136, 210–271. Retrieved from http://eudml.org/doc/149313

Hori, M., Schafer, M. J., & Bowman, D. J. (2009). Displacement dynamics in southern Louisiana after hurricanes Katrina and Rita. Population Research and Policy Review, 28, 45–65.

Hugo, G. (2008). Migration, development and environment (MRS No. 35). Geneva, Switzerland: International Organization for Migration.

Hugo, G. (2011). Future demographic change and its interactions with migration and climate change. Global Environmental Change, 215, 521–533.

Hunter, L. M., Luna, J. K., & Norton, R. M. (2015). Environmental dimensions of migration. Annual Review of Sociology, 41, 377–397.

Hunter, L. M., Murray, S., & Riosmena, F. (2013). Rainfall patterns and U.S. migration from rural Mexico. International Migration Review, 47, 874–909.

International Medical Corps. (2011). Fukushima Prefecture fact sheet. Los Angeles, CA: International Medical Corps.

Inui, Y. (2016). Aid to evacuees by local governments nationwide and local governments affected by the disaster. Journal of Architecture and Planning (Transactions of AIJ), 81, 1851–1858.

Ishikawa, Y. (2012, April 1). Displaced human mobility due to March 11 disaster. 2011 East Japan Earthquake Bulletin of the Tohoku Geographical Association. Retrieved from http://tohokugeo.jp/articles/e-contents29.pdf

Isoda, Y. (2011, April 5). The impact of casualties of 20,000+: Deaths and missing persons by municipalities. 2011 East Japan Earthquake Bulletin of the Tohoku Geographical Association. Retrieved from http://tohokugeo.jp/articles/e-contents1.html

Johnson, R., Bland, J., & Coleman, C. (2008, April). Impacts of the 2005 Gulf Coast hurricanes on domestic migration: U.S. Census Bureau response. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the Population Association of America, New Orleans, LA. Retrieved from https://paa2008.princeton.edu/abstracts/80690

Kayastha, S. L., & Yadava, R. P. (1985). Flood induced population migration in India: A case study of Ghaghara Zone. In L. A. Kosinski & K. M. Elahi (Eds.), Population redistribution and development in South Asia (GeoJournal Library Vol. 3, pp. 79–88). Dordrecht, the Netherlands: Springer.

Koyama, S., Aida, J., Kawachi, I., Kondo, N., Subramanian, S. V., Ito, K., . . . Osaka, K. (2014). Social support improves mental health among the victims relocated to temporary housing following the Great East Japan Earthquake and Tsunami. Tohoku Journal of Experimental Medicine, 234, 241–247.

Lee, E. S. (1966). Theory of migration. Demography, 3, 47–57.

Lu, X., Wrathall, D. J., Sundsøy, P. R., Nadiruzzaman, M., Wetter, E., Iqbal, A., . . . Bengtsson, L. (2016). Unveiling hidden migration and mobility patterns in climate stressed regions: A longitudinal study of six million anonymous mobile phone users in Bangladesh. Global Environmental Change, 38, 1–7.

Mallick, B., & Vogt, J. (2014). Population displacement after cyclone and its consequences: Empirical evidence from coastal Bangladesh. Natural Hazards, 73, 191–212.

Massey, D. S., Arango, J., Hugo, G., Kouaouci, A., Pellegrino, A., & Taylor, J. E. (1994). An evaluation of international migration theory: The North-American case. Population and Development Review, 20, 699–751.

Matanle, P. (2013). Post-disaster recovery in ageing and declining communities: The Great East Japan disaster of 11 March 2011. Geography, 98, 68–76.

McLeman, R. A. (2013). Climate and human migration: Past experiences, future challenges. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

McLeman, R., & Smit, B. (2006). Migration as an adaptation to climate change. Climatic Change, 76, 31–53.

Mueller, V., Gray, C., & Kosec, K. (2014). Heat stress increases long-term human migration in rural Pakistan. Nature Climate Change, 4, 182–185.

National Research Council. (2014). Lessons learned from the Fukushima nuclear accident for improving safety of U.S. nuclear plants. Washington, DC: National Academies Press. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.17226/18294

Nawrotzki, R. J., Hunter, L. M., Runfola, D. M., & Riosmena, F. (2015). Climate change as a migration driver from rural and urban Mexico. Environmental Research Letters, 10(11), 114023. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/10/11/114023

Oda, T. (2011). Grasping the Fukushima displacement and diaspora. 2011 East Japan Earthquake Bulletin of the Tohoku Geographical Association. Retrieved from http://tohokugeo.jp/articles/e-contents24.pdf

Pandit, K. (1997). Cohort and period effects in U.S. migration: How demographic and economic cycles influence the migration schedule. Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 89, 439–450.

Pardo, L. (2005). Statistical inference based on divergence measures. Baton Rouge, FL: Chapman & Hall/CRC.

R Core Team. (2018). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing. Retrieved from https://www.R-project.org/

Randell, H. (2018). The strength of near and distant ties: Social capital, environmental change, and migration in the Brazilian Amazon. Sociology of Development, 4, 394–416. https://doi.org/10.1525/sod.2018.4.4.394

Rigaud, K. K., de Sherbinin, A., Jones, B., Bergmann, J., Clement, V., Ober, K., . . . Midgley, A. (2018). Groundswell: Preparing for internal climate migration. Washington, DC: World Bank.

Rivera, J. D., & Miller, D. S. (2007). Continually neglected: Situating natural disasters in the African American experience. Journal of Black Studies, 37, 502–522.

Sawa, M., Osaki, Y., & Koishikawa, H. (2013). Delayed recovery of caregivers from social dysfunction and psychological distress after the Great East Japan Earthquake. Journal of Affective Disorders, 148, 413–417.

Schultz, J., & Elliott, J. R. (2013). Natural disasters and local demographic change in the United States. Population and Environment, 34, 293–312.

Statistics Bureau Japan. (2011). Report on internal migration in Japan. Tokyo, Japan: Statistics Bureau, Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications. Retrieved from https://www.stat.go.jp/english/data/idou/index.html

Stone, G. S., Henderson, A. K., Davis, S. I., Lewin, M., Shimizu, I., Krishnamurthy, R., . . . Bowman, D. J. (2012). Lessons from the 2006 Louisiana Health and Population Survey. Disasters, 36, 270–290.

Stringfield, J. D. (2010). Higher ground: An exploratory analysis of characteristics affecting returning populations after Hurricane Katrina. Population and Environment, 31, 43–63.

Suzuki, I., & Kaneko, Y. (2013). Japan’s disaster governance: How was the 3.11 crisis managed? New York, NY: Springer.

Takano, T. (2011, April 9). Overview of the 2011 East Japan Earthquake and Tsunami disaster. 2011 East Japan Earthquake Bulletin of the Tohoku Geographical Association. Retrieved from http://tohokugeo.jp/articles/e-contents7.pdf

Takano, T. (2012, April 30). Brief explanation on the regional characteristics of Sanriku Coast (Update to April 19, 2011, report). 2011 East Japan Earthquake Bulletin of the Tohoku Geographical Association. Retrieved from http://tohokugeo.jp/articles/e-contents11.pdf

Thiede, B., & Brown, D. (2013). Hurricane Katrina: Who stayed and why? Population Research and Policy Review, 32, 803–824.

Umeda, S. (2013). Japan: Legal responses to the Great East Japan Earthquake of 2011. Washington, DC: Law Library of Congress, Global Legal Research Center. Retrieved from https://www.loc.gov/law/help/japan-earthquake/index.php

United Nations Scientific Committee on the Effects of Atomic Radiation (UNSCEAR). (2014). Estimated doses to evacuees in Japan for the first year (UNSCEAR 2013 Report, Annex A, Appendix C, Attachment C-18). Vienna, Austria: United Nations Scientific Committee on the Effects of Atomic Radiation. Retrieved from https://www.unscear.org/docs/reports/2013/UNSCEAR_2013A_C-18_Doses_evacuees_Japan_first_year_2014-08.pdf

UNSCEAR. (2014). Levels and effects of radiation exposure due to the nuclear accident after the 2011 Great East-Japan Earthquake and Tsunami (Vol. 1, Report to the General Assembly: Scientific Annex A). New York, NY: United Nations Scientific Committee on the Effects of Atomic Radiation. Retrieved from https://reliefweb.int/report/japan/levels-and-effects-radiation-exposure-due-nuclear-accident-after-2011-great-east-japan

U.S. Geological Survey. (2014). Largest earthquakes in the world since 1900. Reston, VA: U.S. Geological Survey. Retrieved from https://www.usgs.gov/natural-hazards/earthquake-hazards/science/20-largest-earthquakes-world?qt-science_center_objects=0#qt-science_center_objects

Warner, K., Ehrhart, C., de Sherbinin, A., Adamo, S., & Chai-Onn, T. (2009). In search of shelter: Mapping the effects of climate change on human migration and displacement (CARE Report). Geneva, Switzerland: CARE International. Retrieved from https://www.care.org/search-shelter-mapping-effects-climate-change-human-migration-and-displacement-0

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by Mathew E. Hauer. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Mathew E. Hauer and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hauer, M.E., Holloway, S.R. & Oda, T. Evacuees and Migrants Exhibit Different Migration Systems After the Great East Japan Earthquake and Tsunami. Demography 57, 1437–1457 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-020-00883-7

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-020-00883-7