The Lancet Respiratory Medicine ( IF 76.2 ) Pub Date : 2020-03-24 , DOI: 10.1016/s2213-2600(20)30052-7 David M Patrick , Hind Sbihi , Darlene L Y Dai , Abdullah Al Mamun , Drona Rasali , Caren Rose , Fawziah Marra , Rozlyn C T Boutin , Charisse Petersen , Leah T Stiemsma , Geoffrey L Winsor , Fiona S L Brinkman , Anita L Kozyrskyj , Meghan B Azad , Allan B Becker , Piush J Mandhane , Theo J Moraes , Malcolm R Sears , Padmaja Subbarao , B Brett Finlay , Stuart E Turvey

|

Background

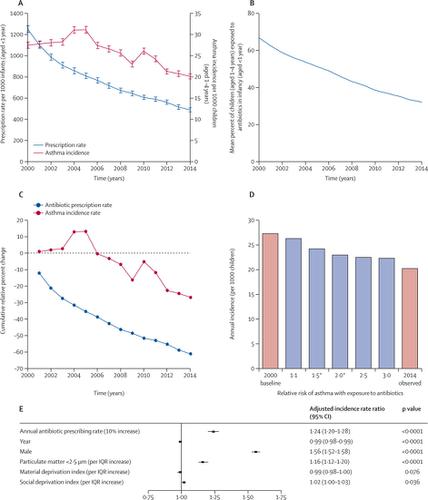

Childhood asthma incidence is decreasing in some parts of Europe and North America. Antibiotic use in infancy has been associated with increased asthma risk. In the present study, we tested the hypothesis that decreases in asthma incidence are linked to reduced antibiotic prescribing and mediated by changes in the gut bacterial community.

Methods

This study comprised population-based and prospective cohort analyses. At the population level, we used administrative data from British Columbia, Canada (population 4·7 million), on annual rates of antibiotic prescriptions and asthma diagnoses, to assess the association between antibiotic prescribing (at age <1 year) and asthma incidence (at age 1–4 years). At the individual level, 2644 children from the Canadian Healthy Infant Longitudinal Development (CHILD) prospective birth cohort were examined for the association of systemic antibiotic use (at age <1 year) with the diagnosis of asthma (at age 5 years). In the same cohort, we did a mechanistic investigation of 917 children with available 16S rRNA gene sequencing data from faecal samples (at age ≤1 year), to assess how composition of the gut microbiota relates to antibiotic exposure and asthma incidence.

Findings

At the population level between 2000 and 2014, asthma incidence in children (aged 1–4 years) showed an absolute decrease of 7·1 new diagnoses per 1000 children, from 27·3 (26·8–28·3) per 1000 children to 20·2 (19·5–20·8) per 1000 children (a relative decrease of 26·0%). Reduction in incidence over the study period was associated with decreasing antibiotic use in infancy (age <1 year), from 1253·8 prescriptions (95% CI 1219·3–1288·9) per 1000 infants to 489·1 (467·6–511·2) per 1000 infants (Spearman's r=0·81; p<0·0001). Asthma incidence increased by 24% with each 10% increase in antibiotic prescribing (adjusted incidence rate ratio 1·24 [95% CI 1·20–1·28]; p<0·0001). In the CHILD cohort, after excluding children who received antibiotics for respiratory symptoms, asthma diagnosis in childhood was associated with infant antibiotic use (adjusted odds ratio [aOR] 2·15 [95% CI 1·37–3·39]; p=0·0009), with a significant dose–response; 114 (5·2%) of 2182 children unexposed to antibiotics had asthma by age 5 years, compared with 23 (8·1%) of 284 exposed to one course, five (10·2%) of 49 exposed to two courses, and six (17·6%) of 34 exposed to three or more courses (aOR 1·44 [1·16–1·79]; p=0·0008). Increasing α-diversity of the gut microbiota, defined as an IQR increase (25th to 75th percentile) in the Chao1 index, at age 1 year was associated with a 32% reduced risk of asthma at age 5 years (aOR for IQR increase 0·68 [0·46–0·99]; p=0·046). In a structural equation model, we found the gut microbiota at age 1 year, characterised by α-diversity, β-diversity, and amplicon sequence variants modified by antibiotic exposure, to be a significant mediator between outpatient antibiotic exposure in the first year of life and asthma diagnosis at age 5 years (β=0·08; p=0·027).

Interpretation

Our findings suggest that the reduction in the incidence of paediatric asthma observed in recent years might be an unexpected benefit of prudent antibiotic use during infancy, acting via preservation of the gut microbial community.

Funding

British Columbia Ministry of Health, Pharmaceutical Services Branch; Canadian Institutes of Health Research; Allergy, Genes and Environment (AllerGen) Network of Centres of Excellence; Genome Canada; and Genome British Columbia.

中文翻译:

儿童减少抗生素的使用,肠道菌群和哮喘的发病率:基于人群和前瞻性队列研究的证据

背景

在欧洲和北美的某些地区,儿童哮喘的发病率正在下降。婴儿期使用抗生素与哮喘风险增加有关。在本研究中,我们检验了以下假设:哮喘发病率降低与抗生素处方减少有关,并由肠道细菌群落的变化介导。

方法

这项研究包括基于人群和前瞻性队列分析。在人群一级,我们使用加拿大不列颠哥伦比亚省(4·700万人口)的行政数据,介绍了抗生素处方和哮喘诊断的年率,以评估抗生素处方(年龄<1岁)与哮喘发生率之间的关系( 1-4岁)。在个体水平上,检查了来自加拿大健康婴儿纵向发展(CHILD)前瞻性出生队列的2644名儿童的全身性抗生素使用(<1岁)与哮喘(5岁)的诊断相关性。在同一队列中,我们对917名儿童进行了机制研究,他们从粪便样本(≤1岁)中获得了可用的16S rRNA基因测序数据,

发现

在2000年至2014年的人口水平上,儿童(1至4岁)的哮喘发病率从每1000名儿童27·3(26·8–28·3)名儿童中,每1000名儿童绝对减少7·1名新诊断到每1000名儿童20·2(19·5-20·8)(相对减少26·0%)。研究期间发病率的降低与婴儿期(年龄<1岁)抗生素的使用减少有关,从每1000名婴儿1253·8剂(95%CI 1219·3–1288·9)减少到489·1(467·6) –每千名婴儿–511·2(Spearman's r= 0·81;p <0·0001)。抗生素处方每增加10%,哮喘的发病率就会增加24%(调整后的发病率比率1·24 [95%CI 1·20-1·28]; p <0·0001)。在儿童队列中,排除呼吸道症状接受抗生素的儿童后,儿童期哮喘的诊断与婴儿抗生素的使用有关(校正比值比[aOR] 2·15 [95%CI 1·37-3·39]; p = 0·0009),具有显着的剂量反应;到5岁时,未接触抗生素的2182名儿童中有114名(5·2%)患有哮喘,而接受一疗程的284名儿童中有23名(8·1%),接受两疗程的49名中的五名(10·2%), 34个中有6个(17·6%)接受了三个或更多课程(aOR 1·44 [1·16-1·79]; p = 0·0008)。肠道菌群的α多样性增加,这被定义为Chao1指数的IQR增加(第25至第75个百分位数),在1岁时与5岁时哮喘风险降低32%相关(IQR的aOR增加0·68 [0·46-0·99]; p = 0·046)。在结构方程模型中,我们发现1岁时的肠道菌群(其特征在于α多样性,β多样性和经抗生素暴露修饰的扩增子序列变异体)是生命第一年门诊抗生素暴露之间的重要介体。和5岁时的哮喘诊断(β= 0·08; p = 0·027)。

解释

我们的研究结果表明,近年来观察到的小儿哮喘发病率的降低可能是婴儿期谨慎使用抗生素的意想不到的益处,这是通过保护肠道微生物群落来实现的。

资金

不列颠哥伦比亚省卫生部药品服务处;加拿大卫生研究所;过敏,基因与环境(AllerGen)卓越中心网络;加拿大基因组;基因组不列颠哥伦比亚省。

京公网安备 11010802027423号

京公网安备 11010802027423号