Migrant remittances are an important source of economic stability in Latin America, but it is unclear whether that stability translates to politics. Many scholars argue that remittances produce democratic attitudes and behaviors (Bastiaens and Tirone Reference Bastiaens and Tirone2019; Bearce and Park Reference Bearce and Park2019; Escribà-Folch et al. Reference Escribà-Folch, Meseguer and Wright2015, Reference Escribà-Folch, Meseguer and Wright2018, Reference Escribà-Folch, Meseguer and Wright2022; Pérez-Armendáriz and Crow Reference Pérez-Armendáriz and Crow2010). Other research asserts that remittances can weaken constituents’ demands for political accountability (Abdih et al. Reference Abdih, Chami, Dagher and Montiel2012; Ahmed Reference Ahmed2012; Goodman and Hiskey Reference Goodman and Hiskey2008). Overlooked in this literature is the variation in local conditions that can shape attitudes and political demands of remittance recipients. Examining responses to local conditions can help us understand why remittance recipients may demand accountability in some situations and not in others.

This article departs from the democracy-autocracy debate surrounding remittances to show how this external income may contribute to presidential breakdowns in Latin American democracies. The analyses show that remittances create a constituency that tolerates presidential interruptions in the form of military coups when local conditions destabilize.Footnote 1 Using data from the Latin American Public Opinion Project (LAPOP), this study shows that remittance recipients are more likely to tolerate a military coup under high corruption and high crime. The results are consistent across different country contexts. To accompany the survey data results, I conducted a cross-country analysis of presidential removals in Latin America using data from Martínez (Reference Martínez2021). This analysis finds that corruption poses an even greater risk to presidents in remittance-dependent countries.

This article will show that external factors, such as migrant remittances, can contribute to presidential interruptions in Latin America. The literature on presidential instability in Latin America since the 1970s emphasizes the role of the economy and institutional factors (Llanos and Marsteintredet Reference Llanos and Marsteintredet2010; Pérez-Liñán Reference Pérez-Liñán2007). Latin American economies remain vulnerable to global economic shocks, which can lead to political instability. Migrant remittances can soften the blow of these economic shocks but can also contribute to political instability through different channels. These external cash flows create a constituency that will support early removal of a president under noneconomic conditions, such as crime and corruption.

I argue that remittance recipient support for early presidential removal stems from how corruption and crime undermine remittance income. Remittances are mainly used for consumption, and this could give recipients a myopic outlook and preferences. Rising crime and corruption may redirect remittance income away from consuming goods. Changing levels of remittances can also affect political preferences (Acevedo Reference Acevedo2020; Tertytchnaya et al. Reference Tertytchnaya, De Vries, Solaz and Doyle2018). Recipients will demand swift political change in order to resume the economic consumption that remittances provide. Thus, remittances add an external factor that contributes to the greater propensity for presidential interruptions, but not democratic breakdown, in Latin America.

This study also contributes to the literature on remittances and political attitudes, highlighting how remittances can generate obstacles for democratic consolidation in Latin America. The ongoing debate as to whether remittances engender democracy is based on the processes of regime change, democratic transition, or autocratic stability. This study emphasizes the role that unstable local conditions hold in shaping political attitudes of remittance recipients in contrast to nonrecipients. Furthermore, this study examines the role of remittances in politics long after democratization and poses questions about how migrant remittances can challenge democratic consolidation and institutional stability.

Presidential Breakdowns and the Political Consequences of Remittances

Though support for coups has generally declined in Latin America, there are systematic factors associated with support for military coups. A comprehensive study by Cassell et al. (Reference Cassell, Booth and Seligson2018) finds specific demographic and attitudinal relationships with support for coups under scenarios of high crime and corruption. The authors find that support for military coups is higher among women and young adults. Meanwhile, support for military coups grows the more insecure a person feels in their own neighborhood and develops greater trust in the military. Support for coups declines with greater education among Latin Americans. Strong support for democracy is associated with less support for military coups, which Pérez-Liñán and Polga-Hecimovich (Reference Pérez-Liñán and Polga-Hecimovich2017) also observe.

Migrant remittances are an external source of income that influences local-level public opinion and political outcomes, which could consequently play roles in presidential removal, such as military coups. The existing literature on remittances has produced a lively debate around whether or not migrant remittances produce democratic attitudes and behaviors.Footnote 2 Although this literature does not explicitly address the role of remittances in presidential interruptions, the mechanisms in this scholarship are applicable. The democratizing effects from remittances should lead recipients to oppose military coups, but recent scholarship raises the possibility of authoritarian attitudes emerging from receiving this external income.

Unlike resource rents or foreign aid, remittance income bypasses governments and goes straight to the recipient citizens. A consensus among scholars of remittances is that this external income produces political autonomy for recipients and less dependence on government-provided goods. Whether remittance recipients become politically active from the increase in income is at the center of the scholarly debate. The theories and findings in the literature can extend to whether recipients differ from nonrecipients in their demands for swift political change, such as presidential removal or military coup.

The democratizing effects of remittances can lead recipients to be tolerant or intolerant of presidential interruptions. Remittances lower the cost of political participation when recipients can protest against and refuse to electorally support incumbents (Escribà-Folch et al. Reference Escribà-Folch, Meseguer and Wright2015, Reference Escribà-Folch, Meseguer and Wright2018, Reference Escribà-Folch, Meseguer and Wright2022). These mechanisms were meant to explain why remittances lead to the downfall of autocracies, but they can also be applied to democratic regimes. Recipients will have less loyalty to incumbents when their economic circumstances depend on family members abroad. This political autonomy and decrease in loyalty to incumbents can provide a foundation for remittance recipients to tolerate a presidential removal, such as a military coup.

However, remittances may weaken support for premature presidential removal through a transmission of norms from abroad instead of the increase in income. Financial remittances often accompany social remittances when the migrant abroad transmits political norms to family members in the home country (Levitt Reference Levitt2001). Through various case studies, scholars have shown that migrants transmit ideas about democracy that can change the political behavior of people in the country of origin (Batista et al. Reference Batista, Seither and Vicente2019; Burgess Reference Burgess2020; Pérez-Armendáriz Reference Pérez-Armendáriz2014; Tuccio et al. Reference Tuccio, Wahba and Hamdouch2019). Assuming that the migrant is located in a democratic country, receivers in the home country will embrace democratic norms and should oppose military coups. In some cases, migrants residing in autocracies will depress support for democracy in the home country (Karakoç et al. Reference Karakoç, Köse and Özcan2017; Rother Reference Rother2009; Barsbai et al. Reference Barsbai, Rapoport, Steinmayr and Trebesch2017). Given that most Latin American migrants reside in the United States, citizens with migrant linkages should have lower support for military coups.

Remittance recipients may oppose presidential removal through their improved economic perceptions. The misattribution thesis argues that remittance recipients favor the status quo because personal and sociotropic economic evaluations are more positive for recipients than for nonrecipients. Research from Latin America and the former Soviet states shows that remittance recipients misattribute credit to local incumbents for their improved economic well-being (Ahmed Reference Ahmed2017; Germano Reference Germano2018; Tertytchnaya et al. Reference Tertytchnaya, De Vries, Solaz and Doyle2018). Consequently, remittances produce acquiescence to local conditions through this misattribution, thus weakening demands for political change. Therefore, the increased income from remittances should produce lower support for military coups because recipients view home country conditions favorably compared to nonrecipients.

Recent scholarship has found that remittance recipients will reveal undemocratic attitudes and preferences in the context of high crime and corruption. In the context of high crime, remittances can pay for private protection and vigilantism (Doyle and López García Reference Doyle and Isabel López García2021; Ley et al. Reference Ley, Olivo and Meseguer2021a, Reference Ley, Olivo and Meseguer2021b; Pérez-Armendáriz and Duquette-Rury Reference Pérez-Armendáriz and Duquette-Rury2021). To protect their remittance income, recipients will become more likely than nonrecipients to support aggressive policing and the deployment of the military in public security (López García and Maydom Reference García, Isabel and Maydom2021a).

Recent research find a statistical relationship between remittances and corruption but it is unclear as to whether international transfers help decrease or increase corruption (Abdih et al. Reference Abdih, Chami, Dagher and Montiel2012; Ahmed Reference Ahmed2013; Berdiev et al. Reference Berdiev, Kim and Chang2013; Tyburski Reference Tyburski2012; Reference Tyburski2014). Recipients can respond to greater corruption by voting out incumbents, disengaging from politics, or paying for the costs of corruption, such as bribery solicitations (Ahmed Reference Ahmed2013; Konte and Ndubuisi Reference Konte and Ndubuisi2020; Pfutze Reference Pfutze2012; Tyburski Reference Tyburski2014). However, it is unclear whether individual recipients will respond to corruption with antidemocratic preferences.

Overlooked in the literature is how remittance recipients respond to different levels of crime and corruption. The current debate on remittances and political change presumes a stable environment. Yet if recent research finds that remittance inflows respond to different levels of crime and corruption, then we should expect recipients to respond as well. López García and Maydom (Reference García, Isabel and Maydom2021b) suggest that recipients will favor greater military presence in public security because they feel greater insecurity due to their higher income. Will this underlying insecurity translate to other antidemocratic preferences, such presidential removal via a military coup? This study seeks to understand how remittances influence recipient political attitudes when local conditions undermine remittance income.

Theory: How Crime and Corruption Undermine Remittance Income to Produce Support for Presidential Removal

An increase in income from remittances improves economic consumption. The incoming funds from abroad may be directed to consuming necessities, human capital investment, and accessing other consumer goods (Fajnzylber and López Reference Fajnzylber and López2008). In less developed countries, remittances reduce consumption instability and act as insurance against economic and noneconomic shocks (Combes and Ebeke Reference Combes and Ebeke2011). As their household income grows, recipients use remittances to invest in human capital. such as education and healthcare for children (Acosta et al. Reference Acosta, Calderón, Fajnzylber and López2008). In many ways, remittances cover the costs of local economic conditions to achieve some level of economic security, and allow households to access markets that were not possible without them.

As remittances improve economic circumstances, recipients develop an improved economic outlook. Receiving remittances translates to positive perceptions of their personal, and national, economic situation (Ahmed Reference Ahmed2017; Germano Reference Germano2018; Tertytchnaya et al. Reference Tertytchnaya, De Vries, Solaz and Doyle2018). The optimism among recipients may explain why they perceive greater social mobility than nonrecipients (Doyle Reference Doyle2015). Thus, remittances pay the startup costs of economic participation and allow recipients to feel relatively positive about local conditions. Local incumbent governments should benefit from the effect remittances have on economic perceptions. However, these outlooks presume that remittance income and local conditions in the home country are stable.

Changes to local conditions can undermine the value of remittances for recipients. Crime and corruption are salient issues in Latin America, and remittance recipients may find that they undermine the value of their external income. For example, high crime rates can divert income from consumption and toward private security (Acevedo Reference Acevedo2009; Ley et al. Reference Ley, Olivo and Meseguer2021a). In a panel study of Mexican municipalities, remittances declined in places that observed in increase in crime (Meseguer et al. Reference Meseguer, Ley and Eduardo Ibarra-Olivo2017). Remittance recipients across African countries are more likely to pay bribes to local government officials for assistance and for public services (Konte and Ndubuisi Reference Konte and Ndubuisi2020). Recipients may find themselves having to reduce their consumption to pay the costs of rising crime and corruption, which reduces the marginal benefits that stem from their remittances. The increased uncertainty from rising crime and corruption will translate to uncertainty about the remittance income they can use for consumption.

A few studies show that a decline in remittances can also affect recipients’ attitudes. Poor economic conditions in migrant destination countries lead to a decline in remittances sent back home (Sirkeci et al. Reference Sirkeci, Cohen and Ratha2012). Tertychnaya et al. (Reference Tertytchnaya, De Vries, Solaz and Doyle2018) show that a decline in remittances negatively affects perception of the economy and executive approval among recipients. Acevedo (Reference Acevedo2020) shows that remittances’ decline will reorient recipients to favor redistribution. However, local conditions can influence the value of disposable remittance income. If recipients find themselves having to redirect their remittance income to account for rising crime and corruption, then the decreasing value of remittances should influence political attitudes just as declining income would.

Therefore, remittance recipients have a stake in local conditions where they spend remittances. If that is the case, we should not expect remittance recipients to be politically apathetic. Remittance recipients show greater interest in politics and participate in local organizations and civic activities than nonrecipients (Córdova and Hiskey Reference Córdova and Hiskey2015; Pérez-Armendáriz and Crow Reference Pérez-Armendáriz and Crow2010). Previous work shows that areas with high levels of remittances respond to corruption and high crime with greater political participation but that the type of participation varies (López García and Maydom Reference García, Isabel and Maydom2021b; Pfutze Reference Pfutze2012; Tyburski Reference Tyburski2012). Whether it is voting out corrupt incumbents or supporting punitive measures to combat crime, I propose that remittance recipients should hold attitudes that support swift political change under costly conditions.

Disruptions to remittance income lead recipients to support political actions that they perceive will decrease the costs of corruption and crime, including presidential removal. High crime and corruption will undermine the value of their remittances and lead recipients to negatively view the local incumbent. To recover the income that was diverted to pay the costs of crime and corruption, recipients will demand swift political change, hoping that they can resume their economic activities with their remittance income. Thus, remittances will create a constituency of citizens that will tolerate and approve hastened political actions, such as presidential removal, in anticipation that a new administration will lower crime and corruption.

I propose that remittance recipients have a myopic outlook that could explain their preferences for presidential removal. Given the importance of remittances for consumption, I argue that recipients have short time horizons in both their economic behavior and political preferences. If crime and corruption interrupt recipients’ consumption, they will demand political change in hopes of preventing further declines in the consumption remittances bring. Recipients will lean toward antidemocratic actions like military coups, assuming that they can return to a higher level of consumption through remittances.

Data and Methods

This study uses the AmericasBarometer survey data from the Latin American Public Opinion Project (LAPOP). The LAPOP surveys are conducted every two years and have asked consistent questions regarding support for coups under high crime and high corruption since 2004 in nearly every Latin American country. Respondents can choose whether a coup is justified when there is a lot of crime and a lot of corruption or whether a coup is not justified. The variables are measured as a binary, where 1 means yes in response to the question.

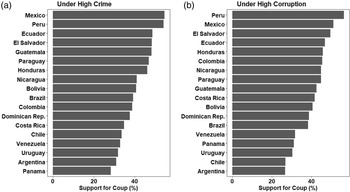

Cassell et al. (Reference Cassell, Booth and Seligson2018) show that support for coups in Latin America generally declined after 2004, and figure 1 here shows how support for coups varies across countries. Though this measure asks respondents about the military taking power under specific circumstances, it allows us to gauge whether respondents approve of swiftly removing an incumbent civilian government. Furthermore, if respondents approve of a military coup in periods of high crime and corruption, then it is reasonable that they would approve of other institutional means of removing a president, such as impeachment or political pressure to force an early resignation.

Figure 1. Mean Support for Coups in Latin America by Country, 2004–2018

Source: LAPOP

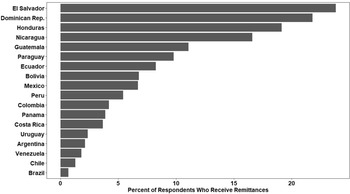

The explanatory variable asks whether the respondent or someone in their household receives remittances. The response is binary, and the question has been asked in LAPOP surveys since 2004. This consistency allows us to analyze remittance recipients as a group over time. Figure 2 shows the variation in remittance receiving among LAPOP survey respondents. Central America and the Caribbean are home to the highest number of remittance receivers as a share of the population, and they tend to be the most remittance-dependent countries in the world. In these countries, remittances tend to exceed 10 percent of the GDP (Sirkeci et al. Reference Sirkeci, Cohen and Ratha2012). The Andean countries, such as Bolivia and Ecuador, are also major recipients of remittances as a share of GDP, and they have high support for military coups.

Figure 2. Percent of LAPOP Respondents Receiving Remittances, 2004–2018

The control variables for the regression analysis include sociodemographic variables along with political and economic attitudes. The sociodemographic variables included are age, gender, income, education, living in an urban area, and employment status. Income is rescaled from 0 to 1, where 0 is the lowest income in the survey and 1 is the largest income category. Education is measured in years of total schooling. Left-right ideology is included and scaled from 0 (left) to 1 (right). Drawing from Cassell et al. (Reference Cassell, Booth and Seligson2018), control variables are incorporated for political attitudes and perceptions that may be correlated with support or opposition to coups. Executive approval and support for democracy are included because higher values on those variables should correlate with lower support for coups. The variables also include controls for support for democracy, trust in the military, and a simple index on support for institutions.Footnote 3 Each of these variables is rescaled from 0 to 1.

Also included are variables that measure economic and political evaluation, since they both are associated with remittances and support for coups. Remittances can influence how recipients perceive political and economic conditions at the local and national levels (Ahmed Reference Ahmed2017; Crow and Pérez-Armendáriz Reference Crow and Pérez-Armendáriz2018; Doyle Reference Doyle2015; Tertytchnaya et al. Reference Tertytchnaya, De Vries, Solaz and Doyle2018). Remittances lead to higher levels of economic evaluation, which should translate to lower support for coups. The main models in the analysis use questions regarding current economic evaluations at the personal (pocketbook) level and the national (sociotropic) level. The appendix includes models in which retrospective economic evaluation variables replace the concurrent variables. Given that the dependent variables make references to crime and corruption, I control for perceptions of neighborhood insecurity and corruption. I also include a control for crime victimization.

The analysis uses a linear probability model to estimate the effects of remittances on support for coups in Latin America. The models have country-year fixed effects with clustered standard errors at the country-year level. Other models add contextual variables to see if they influence the effect of remittances on coup support. The Polity score is used to control for the institutional context of the country. Weak democracies can be vulnerable to military coups, while strong democracies may have developed norms that weaken support for military coups (Cassell et al. Reference Cassell, Booth and Seligson2018; Lehoucq and Pérez-Liñán Reference Lehoucq and Pérez-Liñán2014). Remittances as a share of the GDP are included to account for national economic dependency on remittances and the multiplier effect that can produce democratic pressures (Bastiaens and Tirone Reference Bastiaens and Tirone2019; Bearce and Park Reference Bearce and Park2019). Other scholars argue that economic dependence on remittances will produce political disengagement (Abdih et al. Reference Abdih, Chami, Dagher and Montiel2012; Goodman and Hiskey Reference Goodman and Hiskey2008).

This analysis also examines how remittance recipients differ in contexts of high crime and corruption. For crime, it uses a two-year moving average in homicide rates from the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC 2022). For corruption, it calculates a two-year moving average of the number of presidential scandals, using data from Martínez (Reference Martínez2021). In addition, subset analysis is employed to examine whether countries with a history of presidential removal during their democratic period influence remittance recipients.

Results

Across Latin America, remittance recipients demonstrate greater support for military coups than do nonrecipients. Table 1 presents results from the linear probability model for support for coups under high crime and high corruption, respectively. Across the four models, remittance recipients are at least 3 percent more likely to support coups than nonrecipients. Results are consistent and robust when controlling for political and economic evaluations. The control variables yield similar results to those of Cassell et al. (Reference Cassell, Booth and Seligson2018).Footnote 4 The coefficients for sociodemographic variables show the same direction and statistical significance. Those with greater executive approval and support for democracy are less likely to support coups. Greater trust in the military and neighborhood insecurity are associated with greater support for coups, while corruption perceptions yield a null result. Crime victimization increases support for military coups under both high crime and corruption.

Table 1. Remittances and Support for Coups Under High Crime and Corruption

*p < 0.1; **p < 0.05; ***p < 0.01.

Notes: Models include country-year fixed effects. Standard errors are clustered at country-year.

Support for coups among remittance recipients also responds to contextual factors to varying degrees. Remittance recipients favor coups across democratic contexts and different levels of remittances as a share of the economy (appendix table A1). The remittance variable is positively associated with support for coups across the range of Polity scores in Latin America. While the interaction with Polity is significant and negative, the magnitude of the interaction is small and driven by scores for Venezuela in 2010 and 2012.Footnote 5 Omitting these two country-years would lead to a null interaction effect. This would suggest that recipients would favor coups even in strong democratic contexts.

Remittance recipient support for coups is present even where these inflows make up a relatively small share of the economy. The positive interaction effect between the binary remittance-receiving variable with the remittances as a share of the GDP indicates that recipients show greater tolerance for coups under larger inflows of remittances into the economy (table A1). Furthermore, recipients show stronger support for coups in country-years when remittances constitute less than 10 percent of the GDP (table A2). These results suggest that remittance-dependent countries are not driving the results for the remittance-receiving variable from the LAPOP surveys.

Given the variation in homicide rates and corruption across and within Latin American countries, remittance recipients may hold stronger support for coups under costly local conditions. Countries experiencing greater violence and corruption will more probably push remittance recipients to support military coups (table A3). A two-year average of homicide rates is used as a measure of violence at the country level and logged to account for skewness (UNODC 2022). For corruption, the Control of Corruption indicator from the World Bank’s Worldwide Governance Indicators is used (Kaufman and Kraay Reference Kaufman and Kraay2022). For ease of interpretation, I use an inverse of the score, so that higher values mean greater corruption.

The interaction effects between the individual-level remittance variable and the country-level variables are positive and statistically significant. At the lowest levels of crime and corruption, the remittance variable is small and not significant in most of the interaction models. As crime and corruption increase, support for coups grows in the country, but that support is even greater among remittance recipients. Thus, while citizens in countries with higher levels of corruption and violence show greater support for coups, remittance recipients show even greater support than the nonrecipient populations.

Remittance recipients having greater perceptions of higher insecurity or corruption do not drive support for military coups. Remittance recipients are found to have different views and experiences with crime and corruption (López García and Maydom Reference García, Isabel and Maydom2021b; Konte and Ndubuisi Reference Konte and Ndubuisi2020). A series of interaction results with neighborhood insecurity, corruption perception, and crime victimization did not yield significant results (tables A5–A6). Remittances are not affected by the interaction with these variables. Crime and corruption perceptions, along with crime victimization, have positive and independent effects on support for coups, but their interactions with remittances are null. Therefore, different levels of perception of crime and corruption between recipients and nonrecipients are not driving recipient support for coups.

Remittance recipients do not differ in contexts where presidential removals have occurred. Using Martínez’s (Reference Martínez2021) data on presidential removal, I find that remittances do not respond to the number of presidential removals the respective country has experienced since democratization (table A6). Moreover, the effect of receiving remittances is similar in country cases that have not experienced presidential removals to those that have experienced more than one. When interacting remittances with years since the last presidential removal, the results suggest that recipients remain supportive of military coups shortly after a president has been removed.

The work on remittances recognizes the potential endogeneity in remittance recipients. Receiving remittances is not random, as the emigration that precedes it is self-selected and often not representative of the general population (Fajnzylber and López Reference Fajnzylber and López2008; Naude Reference Naudé2010). As a robustness check, I used matching on pretreatment variables, such as sociodemographic factors along with ideology, to examine the effect of remittances on support for a coup.Footnote 6 The matching results show a significant difference between recipients and nonrecipients in support for coups under crime, but results are weaker under corruption.Footnote 7

The Role of Economic Perceptions and Income

The main analysis accounted for political and economic perceptions that can influence remittances’ effect on support for coups. Remittances remained positively associated with support for coups, despite controlling for these relevant factors at the individual and contextual levels. However, it is possible that other conditional effects for remittances can produce support for coups. The income boost that comes from remittances should improve their personal and national economic evaluations. In this case, such economic evaluations should drive recipients’ preferences for a military coup under costly conditions. To test for alternative theories in the research on the political economy of remittances, I used interaction models with economic evaluations and income. Recipients with positive economic perceptions and higher income show greater support for coups.

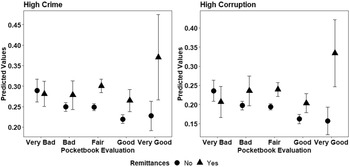

Interacting remittances with economic evaluations provides an appropriate test of the misattribution hypothesis. I used concurrent economic evaluations at the pocketbook and sociotropic levels. These questions ask respondents about their current perceptions of their personal and national economies. Remittance recipients with positive evaluations of their personal economies tend to have a higher approval of military coups (table A13). Figure 3 plots the interaction results to show that remittances have higher predicted values of support for coups under positive economic evaluations. There are significant differences between recipients and nonrecipients when evaluations range from fair to positive. While nonrecipients show a decrease in support for coups as evaluations increase, recipients move in the opposite direction. When recipients evaluate their personal economic situation as “very good,” they show stronger support for coups. The interaction with sociotropic evaluation yields a significant and positive result, but only for high crime and not for corruption.

Figure 3. Predicted Values of Support for Coups by Remittances and Pocketbook Evaluation

The significant interactions using concurrent economic evaluations also suggest that remittance recipients probably have a myopic outlook. When replacing concurrent economic evaluation variables with retrospective variables, the interactions yield null results (table A14). These two interaction models suggest that remittance recipients tend to respond to current conditions, rather than considering a longer time horizon. Furthermore, remittances have a positive and significant association with pocketbook evaluations but not with sociotropic ones, further highlighting how the impact of remittances in the household economy translates to political preferences (table A15). The support for military coups and presidential interruptions may reflect a demand among remittance recipients for swift political change that will enable them to resume the economic activities they engaged in before conditions deteriorated.

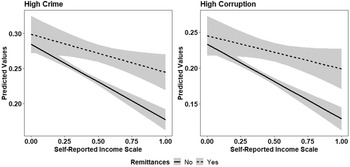

Recipients may recognize that their economic participation depends on remittance income, which would lead them to be more attentive to local conditions. The main results found that higher reported income is associated with declining support for coups (table A16). However, that effect is weaker among remittance recipients. Figure 4 shows that almost throughout the income scale, remittance recipients are more likely than nonrecipients to favor coups. The difference between them is larger among those with higher income. These results reflect how increased remittances raise the stakes of local conditions and lead to support for coups. The positive interaction across the pocketbook evaluation and reported income shows that when remittances provide greater economic security, recipients prefer a coup to maintain that stability and economic participation.

Figure 4. Predicted Values of Support for Coups by Remittances and Self-Reported Income

Noneconomic Channels

I did not find disengagement to drive remittance recipient support for coups. The intent to emigrate variable can control for respondents who “vote with their feet,” as emigration can be seen as disengagement from their home country’s politics. Remittances lower the cost of migration through both income and network effects (Massey et al. Reference Massey, Joaquín Arango and Kouaouci1993). If crime and corruption were to worsen, recipients might simply opt out by moving away rather than bearing the costs of instability. Thus, we should expect remittance recipient support for coups to be driven by those who do not intend to migrate. The interaction between remittances and intention to emigrate did not yield significant results at 95 percent confidence (table A17). Recipients do not differ in their support for coups regardless of intention to migrate.

Interest in politics and political discussion can be proxies to test for disengagement. LAPOP consistently asks respondents about their level of interest in politics and the frequency with which they discuss politics with others. Remittance recipients tend to have higher political interest and more frequent political discussions than nonrecipients (table A17). However, recipients’ support for coups is independent of the levels of political interest and political discussion they report (table A17). Thus, recipients are not as disengaged with politics, but their interest in politics is not driving support for coups.

The analysis tested for possible norm diffusion and social remittances by using variables that measure communication frequency with family abroad and migrant destination. Those who frequently communicate with family abroad or have family members residing in democratic countries should be exposed to greater democratic norms (Miller and Peters Reference Miller and Peters2020; Tuccio et al. Reference Tuccio, Wahba and Hamdouch2019). Therefore, the expectation is that Latin Americans with migrant linkages outside of financial remittances should have lower support for military coups.

The analysis included a dummy variable for whether a respondent has family in the United States, which is a major destination for Latin American migrants (Ratha et al. Reference Ratha, Eigen-Zucchi and Plaza2016). The remittance variable continues to be positive and significant with support for coups (table A18).

The inclusion of communication and family in the United States, along with interactions with remittances, does not yield significant results. Nevertheless, remittances still show a strong association with support for coups. The results suggest that financial remittances’ association with support for coups is independent of democratic diffusion. The null results are surprising, given the literature on democratic diffusion. Future research will benefit from studying the lack of democratic diffusion from migrants living in democratic destination countries. One possibility is that the information about crime and corruption in the home country leads migrants abroad to favor military intervention in politics (Acevedo and Ocampo Reference Acevedo and Ocampo2022).Footnote 8

A limitation in the analysis is that while remittance recipients hold greater tolerance for military coups than nonrecipients do, actual military overthrow of governments is rare in Latin America. Military coups are an extreme case of presidential removal. Remittances produce a constituency that is tolerable to forced removal of presidents, and this can provide a signal to elite political actors (Casper and Tyson Reference Casper and Tyson2014).

Are Presidents in Remittance-dependent Countries at Greater Risk of Removal?

A significant feature of Latin American democracies since the late twentieth century has been executive instability with regime stability. Military coups are rare, but presidential removals have increased through legal mechanisms and early resignations (Llanos and Marsteintredet Reference Llanos and Marsteintredet2010; Pérez-Liñán Reference Pérez-Liñán2007). Between 1978 and 2016, 19 constitutional presidents were removed without military intervention (Pérez-Liñán and Polga-Hecimovich Reference Pérez-Liñán and Polga-Hecimovich2017).

Presidents can be removed from office through institutional means, such as impeachment and early resignation (Marsteintredet Reference Marsteintredet2014; Marsteintredet and Berntzen Reference Marsteintredet and Berntzen2008). Sometimes these presidential removals emerge against a backdrop of social unrest. Presidential crises have occurred with slightly greater frequency since 1978, and these events rarely lead to regime breakdown or disruption (Pérez-Liñán Reference Pérez-Liñán2007, 62).

Institutional characteristics, economic factors, and specific events are associated with the likelihood of presidential removal. Executive-legislative relations and party systems are important explanatory factors (Llanos and Marsteintredet Reference Llanos and Marsteintredet2010; Marsteintredet Reference Marsteintredet2014; Martínez Reference Martínez2021; Pérez-Liñán Reference Pérez-Liñán2007). Economic performance, measured through recession or inflation, is theorized to threaten presidential survival, but studies do not find consistent empirical support for that hypothesis (Edwards Reference Edwards2015; Hochstetler and Edwards Reference Hochstetler and Edwards2009). Corruption scandals and antigovernment protests can create conditions to pressure for Latin American presidents to be removed before the end of their term (Edwards Reference Edwards2015; Martínez Reference Martínez2021). Institutional factors have strong explanatory power, whereas the economy and noninstitutional factors yield mixed results.

In terms of remittances, studies find that their inflow has an effect on the fate of political regimes, which has implications as to whether remittances affect presidential stability (Ahmed Reference Ahmed2012; Escribà-Folch et al. Reference Escribà-Folch, Meseguer and Wright2022). Remittances produce political autonomy, meaning that recipients have less loyalty to the state and can substitute private goods for government goods. This could lead to a disengaged citizenry, which would allow governments to divert public resources to strengthen regime stability (Abdih et al. Reference Abdih, Chami, Dagher and Montiel2012; Ahmed Reference Ahmed2012). In this scenario, remittances produce an incumbency advantage that should decrease a president’s risk of removal. On the other hand, remittances lower the cost of political participation and create new political demands that can eventually lead to regime change (Escribà-Folch et al. Reference Escribà-Folch, Meseguer and Wright2015, Reference Escribà-Folch, Meseguer and Wright2022; Bearce and Park Reference Bearce and Park2019; Bastiaens and Tirone Reference Bastiaens and Tirone2019). While these works focus on remittances and regime type, they can be applied to the fate of incumbents in a regime. Remittances can pose a greater risk to democratically elected presidents in unstable contexts, such as increasing crime and corruption.

To complement the earlier individual-level analysis, I used Martínez’s (Reference Martínez2021) data on presidential removals to estimate the risk that remittances may pose to presidents in Latin America. I used a Cox Proportional Hazards Model to test the risk that remittances have had for presidents in Latin America since the Third Wave of democratization.Footnote 9 The event of interest is a presidential removal when “a president is forced to leave office early and is replaced by a civilian government” (Martínez Reference Martínez2021, 689). Time for each presidential administration is measured in days from their inauguration to when the president leaves office.

The results of the survival analysis use the same variables as Martínez (Reference Martínez2021), which focus on institutional factors in estimating risk of removal. in addition to scandals and economic growth (see Martínez Reference Martínez2021, table 2, cols.1and 2). The direction and statistical significance of the coefficients are similar to those in Martínez (Reference Martínez2021). Greater numbers of presidential scandals and poor economic growth produce increased risk of presidential removal. Columns 1 and 2 add remittances as a share of the GDP (logged), and they do not have an independent effect on risk of removal. Remittance-dependent economies do not have a statistically significant effect on presidential removal on their own.

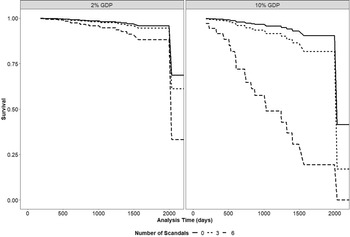

However, similar to the survey analysis, remittances are influential under high corruption. While scandals raise the risk of presidential removal regardless of remittances, presidents in remittance-dependent countries face greater risk (table A19). Figure 5 plots the survival function based on the interaction between presidential scandals and remittances. Holding the covariates at their means, it compares survival functions between different levels of remittances (2 percent and 10 percent of GDP) and scandals (0, 3, and 6). The left panel plots the survival functions by number of scandals in a country where remittances are 2 percent of the GDP. The survival rates remain high for presidents in this scenario, and the rates decline at a greater rate, at six scandals.

Figure 5. Survival Functions for Remittances-Scandals Interaction Results

The right panel shows survival functions for a country where remittances make up 10 percent of the GDP. In this scenario, the effect of scandals is stronger than in cases listed in the left panel. At a high amount of scandals (6), presidents are at much greater risk for removal in a remittance-dependent country than in a nondependent country. This country-level analysis reflects the individual-level analysis, in which remittances are associated with presidential interruptions under high levels of corruption.

Remittances do not pose an additional risk to Latin American presidents serving in regimes with poor economic performance. The null interaction effect between remittances and economic growth indicates that remittances do not respond to economic conditions as they do to noneconomic conditions like corruption and presidential scandals. The countercyclical nature of remittances could explain the lack of results, as migrants send more money to the home country when the latter faces hard times (Frankel Reference Frankel2011). Future research should investigate whether the misattribution effect for remittances is observable only for economic conditions, as opposed to noneconomic conditions like violence and corruption.

Are Remittances Bad for Democracy?

This article has shown that remittances create a constituency that would tolerate presidential interruptions in the form of military coups, but they are conditional to local circumstances. The survey questions on tolerance and support for coups highlight high crime and corruption as justification to change the civilian government. The survival analysis shows that presidents face a greater risk of removal due to scandal in a remittance-dependent country. While remittance recipients may not punish incumbents for poor economic performance, they can be a threat when crime and corruption increase.

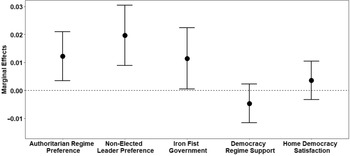

Despite support for military coups and presidential interruptions, it is unclear whether remittance recipients will turn authoritarian. The demand for military coups occurs under conditions of high crime and corruption. The LAPOP surveys feature questions about preferences for authoritarian government and support for democracy. Remittance recipients appear to slightly favor authoritarianism but are not significantly different from nonrecipients in their views on democracy (table A20).

Figure 6 presents the marginal effect of the remittance-receiving variable on regime preferences. The first three effects may suggest that recipients support authoritarianism. However, the survey questions reference particular characteristics about the regime, which could influence recipients more than nonrecipients.Footnote 10 The results highlight that remittance recipients may be more sensitive to local political conditions than nonrecipients and show that problems such as crime and corruption will drive such attitudes. Despite underlying support for authoritarianism, recipients are not statistically different in how much they support democracy. These mixed results may speak more for the demand for a stable environment than normative support for regime types.

Figure 6. Remittances and Regime Attitudes

These results call into question whether remittance recipients are willing to invest in a democracy. Previous research argues that remittance recipients will either divest or invest in democracy, since they hold greater interest in politics and are more likely to participate in civic organizations. One possible interpretation is that remittance recipients are willing to make tradeoffs in which they tolerate antidemocratic actions under a democratic regime. Given the literature that supports democratic norm diffusion, what exactly are the democratic norms that recipients adopt? The literature reveals that remittances may show democratic behavior through local organizations and government but national politics are viewed differently.

The effect remittances may have on political instability under democracies has received little attention. The remittances-democratization debate implicitly assumes that the local context recipients live in is stable. Previous research shows the democratizing effect of remittances among Latin Americans, while recent research has begun to challenge this claim. This article has highlighted that when a country faces political crises, it is not a forgone conclusion that remittance recipients will defend democracy. Inflows of remittances may stall democratic consolidation and nurture democratic backsliding if local conditions worsen.

The migrant who sends remittances is a missing actor in this story. Understanding how remittance senders view current conditions in their home country is vital in theorizing the political effects of remittances. Remittances respond to home-country political conditions (Meseguer et al. Reference Meseguer, Ley and Eduardo Ibarra-Olivo2017; O’Mahony Reference O’Mahony2013; Yang and Choi Reference Yang and Choi2007), yet there are few data on individual remittance senders. Given the importance of remittances to the household economy, sender status gives them asymmetrical influence on the political beliefs of the receivers (Pérez-Armendáriz Reference Pérez-Armendáriz2014). Yet we are not sure what information the sender knows about current home-country conditions. Acevedo and Ocampo (Reference Acevedo and Ocampo2022) reveal that worsening conditions in Latin America could produce antidemocratic diffusion. Given that remittances compound the risk of removal for presidents across Latin America, the source of that risk may be in the diaspora.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/lap.2022.68