Abstract

The drivers of public support for international organizations (IOs) are multifaceted and contested. Focusing on the US, we argue that citizens weigh elite cues about the financial burden associated with funding IOs and the influence over IOs that such funding yields. Moreover, we identify political ideology as a powerful moderator – theorizing that conservatives should respond more positively to cues about US influence and more negatively to cues about financial costs than liberals. We find support for the core theory, but also counterintuitively find that the negative effect of the cost treatment manifests primarily amongst liberals as opposed to conservatives. A second, pre-registered experiment reveals that conservatives support increasing funding to IOs to secure US influence, and may even support increasing taxes to do so, especially when cued by a co-partisan. By contrast, liberals who learn that funding provides influence prefer to cut funding to IOs, even when cued by a co-partisan.

Similar content being viewed by others

Data Availability

The dataset generated by the survey research analyzed for the current study are available in the Dataverse repository and the Review of International Organizations’ webpage.

Notes

As quoted in (Milner & Dustin, 2012, 3).

Morse (2014).

Data from the Chicago Council’s Worldviews 2002 Report and Global Views poll from 2008 suggest these figures are broadly consistent with past decades.

Andersen et al. (2006).

Clark and Dolan (2021).

For related work on how ideology and elite rhetoric shape public attitudes toward the international order, see Lee and Prather (2020).

Shendruk, Amandam, Laura Hillard, and Diana Roy. “Funding the United Nations.” Council on Foreign Relations. June 8, 2020. http://on.cfr.org/3odpzxs.

Browne, Ryan. “Trump Administration to Cut its Financial Contribution to NATO.” CNN. November 28, 2019. https://cnn.it/3cuIKx4. Also see “Brazil’s President Says NGO Funding will be Tightly Controlled.” Reuters. January 7, 2019. https://reut.rs/2T2tvnk on Brazilian President Bolsonaro, who has made similar statements.

Drezner (2008).

This is consistent with the findings of Kiratli (2020), who argues that people may be particuarly dissatisfied when there is a gap between economic expectations and the perceived utility of IOs, which is especially pronounced for voters in countries that contribute more to IOs.

Our samples are are broadly representative based on education, income, gender, and age, as shown in Table A5.

Hurst et al. (2017).

Cassata, Donna. “Seeking Showdown With Clinton, Gingrich Gets One With GOP.” CNN. March 18, 1998. https://www.cnn.com/ALLPOLITICS/1998/03/18/cq/foreign.policy.html

Webb, Whitney. “Leaked WikiLeaks Doc Reveals US Military Use of IMF, World Bank.” Mint News. February 7, 2019. https://bit.ly/3aMvna5

Mutz and Kim (2017).

Brutger and Rathbun (2021).

Milner and Dustin (2012). While Milner and Tingley argue that publics prefer bilateral solutions to multilateral ones when they desire control, powerful states may possess comparable influence over IOs in some cases while yielding other benefits, such as a veil of legitimacy.

For example, Rathbun et al. (2016).

Dellmuth and Scholte (2018).

Rathbun (2007).

Brutger (2021).

Rathbun (2007).

Brutger and Kertzer (2018).

Rathbun (2007).

Rathbun (2007).

Jost (2017).

Casler and Groves (2021).

We use social values theory to predict heterogenous effects across ideology (and partisanship), since ideology and partisanship are some of the most salient dimensions guiding the formation of political coalitions and the policy making process. While we could have attempted to directly measure core values, we follow recent scholarship, such as Brutger (2021) and Casler and Groves (2021), by focusing on the politically salient dimensions that are likely to be more meaningful to political audiences. For example, policy advisors and politicians seeking to build a domestic coalition are likely to ask whether liberals, moderates, and/or conservatives will support a policy, or in the American context whether Democrats and/or Republicans will support a policy. However, it is quite unlikely that political actors will consider whether individuals who are high or low in specific values, such as self-transcendence values, are likely to support or oppose a policy.

As these examples suggest, the US is the largest contributor to organizations with various institutional design features. This logic then is not specific to any one voting scheme or governance framework.

See e.g. Trump on NATO and the WHO — Browne, Ryan. “Trump Administration to Cut its Financial Contribution to NATO.” CNN. November 28, 2019. https://cnn.it/3cuIKx4

Cassata, Donna. “Seeking Showdown With Clinton, Gingrich Gets One With GOP.” CNN. March 18, 1998. https://www.cnn.com/ALLPOLITICS/1998/03/18/cq/foreign.policy.html

Ibid.

The experiment was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of California, Berkeley, under protocol 2019-07-12427.

E.g., Clark and Dolan (2021).

Smith, R. Jeffrey. “Republicans Seek to Curb UN Funding.” Washington Post. January 23, 1995. https://wapo.st/3jrktdH; “Trump Calls for World Bank to Stop Loaning to China.” Reuters. December 6, 2019. https://reut.rs/3iR3T7b

See Guisinger and Saunders (2017) on elite cues and international issues.

For examples of publications in leading political science journals using Dynata (SSI) studies, see e.g. Brutger and Kertzer (2018), Brutger and Strezhnev (2022), and Bush and Prather (2020). We discuss ethics and human subjects principles in detail in Appendix §8. The Appendix is available on the Review of International Organizations’ webpage.

See Appendix Table A1.

See Appendix Table A5.

See Brutger et al. (2022), which shows that salient cue-givers can generate larger treatment effects.

We specifically make use of IO mandates from their founding documents and websites.

As shown below, the influence treatments specify the formal rules that give control through the ability to veto, which allow the US to exert significant influence. This means that the treatment potentially combines public concerns about control and influence in IOs, which is representative of how the issues are frequently discussed by the media and elites, and is appropriate given the close connection between control and influence. For more on state influence and control in IOs, see Novosad and Werker (2014) and Stone (2011).

News coverage similarly juxtaposes discussions of US influence with cost considerations – see e.g. Harris, Gardiner. “Trump Administration Withdraws US From U.N. Human Rights Council.” New York Times. June 19, 2018. https://nyti.ms/3e7vK15; Armus, Teo. “Trump Threatens to Permanently Cut WHO Funding.” May 19, 2020. Washington Post. https://wapo.st/2Y3R9CC.

See Brutger et al. (2022), which finds that longer treatment text reduces the size of average treatment effects.

We randomized whether respondents who received this treatment received the influence or cost condition first.

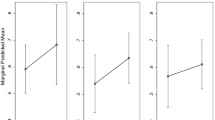

These results also hold when we include socio-demographic covariates (Appendix Table A7).

The measure of ideology and a discussion of its use is provided in Appendix §2.4

In the subset analysis, each respondent is coded as liberal if they selected “slightly liberal,” “liberal,” or “extremely liberal” with conservatives coded in the corresponding manner.

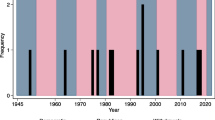

With respondents’ stronger priors toward the UN, we also recognize that conservatives have become muchmore negative toward the UN, especially since the 9/11 attacks (Pushter, 2016).

We randomized the order of the main dependent variable and the potential mediators, as recommended.

Dellmuth and Scholte (2018).

Brutger and Rathbun (2021).

Brutger and Rathbun (2021).

Dellmuth and Scholte (2018).

Once again, we re-scale the seven-point conservatism variable to a 0-1 scale for ease of interpretation.

Notably, the average fairness, legitimacy, and trust values are much higher for liberals than conservatives. Specifically, liberals average 3.64, 3.45, and 3.91 out of five for fairness, trust, and legitimacy respectively, while conservatives average 3.10, 2.91, and 3.23.

Had we directly measured whether individuals place a higher value on equality versus equity, we would have likely found a larger negative effect of the influence treatment on those who prioritize equality. This means that the potential bias of proxying for core values with ideology may lead to our estimates being relatively conservative, since ideology is not as precise a measure of the underlying value.

Jost (2017).

Our sample is balanced on key observables, as is shown in Appendix Figure A8. To enhance data quality we implemented a series of respondent screening questions and procedures, which we detail in the Appendix Section 6.1, along with a discussion of some of the strengths and limitations of the sample. Descriptive statistics for the sample can be found in Appendix Table A9. Comparisons to Census benchmarks can be found in Table A5.

Cassata, Donna. “Seeking Showdown With Clinton, Gingrich Gets One With GOP.” CNN. March 18, 1998. https://www.cnn.com/ALLPOLITICS/1998/03/18/cq/foreign.policy.html

House Committee on Appropriations. Subcommittee on Foreign Operations and Related Agencies, Foreign Assistance and Related Programs Appropriations for 1982: Hearings before a Subcommittee of the Committee on Appropriations, 97th Congress, First Session.

Hennigan, W.J. “We Reject Globalism: President Trump Took American First to the United Nations.” Time. September 25, 2018. https://bit.ly/3Bo85UO

Schlipphak et al. (2022)

Brutger (2021).

See e.g., Zaller (1992).

See e.g., Hiscox (2006).

See e.g. Cassata, Donna. “Seeking Showdown With Clinton, Gingrich Gets One With GOP.” CNN. March 18, 1998. https://www.cnn.com/ALLPOLITICS/1998/03/18/cq/foreign.policy.html and the 2018 US budgetary documents at https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/BUDGET-2018-BUD/pdf/BUDGET-2018-BUD.pdf.

Since the survey provided information about funding departments (Defense, Education, Transportation, etc.) we felt that the most similar comparison was to include funding for the State Department and related foreign policy allocations, as opposed to the specific line-item for the IO funding.

See Ibid p. 50.

We tuned the models to ensure that exclusivity and semantic coherence were high. For democrats, we run the model with six topics. For republicans, we run it with five topics.

Guisinger and Saunders (2017).

Dellmuth et al. (2021).

See Brutger et al. (2022).

References

Abbott, K. W., & Snidal, D. (1998). Why states act through formal international organizations. The Journal of Conflict Resolution, 42(1), 3–32.

Andersen, T. B., Hansen, H., & Markussen, T. (2006). US Politics and World Bank IDA-lending. The Journal of Development Studies, 42(5), 772–794.

Barnea, M. F, & Schwartz, S. H (1998). Values and voting. Political Psychology, 19(1), 17–40.

Barnett, M. N. (1999). Martha finnemore the politics, power, and pathologies of international organizations. International Organization, 53(4), 699–732.

Barrett, S. (2005). Environment and statecraft: The strategy of environmental Treaty-Making Oxford. New York: Oxford University Press.

Bechtel, M. M, & Scheve, K. F (2013). Mass support for global climate agreements depends on institutional design. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 110(34), 13763–13768.

Brewer, P. R. (2001). Value words and lizard brains: Do citizens deliberate about appeals to their core values?. Political Psychology, 22(1), 45–64. 10.1111/0162-895X.00225.

Brooks, S. G. (2008). William curti wohlforth world out of balance: International relations and the challenge of american primacy. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Brutger, R. (2021). The power of compromise: Proposal power, partisanship, and public support in international bargaining. World Politics, 73(1), 128–166.

Brutger, R., & Strezhnev, A. (2022). International investment disputes, media coverage, and backlash against international law. Journal of Conflict Resolution, https://doi.org/10.1177/00220027221081925.

Brutger, R., & Rathbun, B. (2021). Fair share? Equality and equity in American attitudes toward trade. International Organization, 75(3), 880–900.

Brutger, R., & Kertzer, J. D (2018). A dispositional theory of reputation costs. International Organization, 72(3), 693–724.

Brutger, R., Kertzer, J. D., Renshon, J., Tingley, D., & Weiss, C. M. (2022). Abstraction and detail in experimental design. American Journal of Political Science, Forthcoming.

Brutger, R., & Morse, J. C (2015). Balancing law and politics: Judicial incentives in WTO dispute settlement. The Review of International Organizations, 10(2), 179–205.

Brutger, R., & Li, S. (2022). Institutional design, information transmission, and public opinion: making the case for trade. Journal of Conflict Resolution. FirstView.

Buchanan, A., & Keohane, R. O. (2006). The legitimacy of global governance institutions. Ethics and International Affairs, 20(4), 405–437.

Bush, S. S., & Prather, L. (2020). Foreign meddling and mass attitudes toward international economic engagement. International Organization, 74(3), 584–609.

Carnegie, A. (2015). Power plays: How international institutions reshape coercive diplomacy. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Carnegie, A., & Carson, A. (2019). The disclosure dilemma: Nuclear intelligence and international organizations. American Journal of Political Science, 63(2).

Carnegie, A., Clark, R., & Zucker, N. (2021). Global governance under populism: the challenge of information suppression. Working paper. https://bit.ly/3y3uw12.

Casler, D., & Groves, D. (2021). In Perspective taking through partisan eyes. International Political Economy Society. https://www.internationalpoliticaleconomysociety.org/sites/default/files/paper-uploads/2021-10-14-00_10_16-caslerdon@gmail.com.pdf. Accessed 1 Oct 2022.

Chaudoin, S., Livny, A., & Gaines, B. (2019). Survey design, order effects and causal mediation analysis. Working Paper. http://www.stephenchaudoin.com/cma_cgl.pdf. Accessed 1 Oct 2022.

Clark, R. (2021). Pool or Duel? Cooperation and competition among international organizations. International Organization, 75, 1133–1153.

Clark, R. (2022). Bargain down or shop around? Outside options and IMF conditionality. Journal of Politics, Forthcoming. https://bit.ly/34C6f83.

Clark, R., & Dolan, L. (2021). Pleasing the principal: U.S. Influence in World Bank policymaking. American Journal of Political Science, 65(1), 36–51.

De Vries, C. E. (2018). Euroscepticism and the future of the European Union. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

De Vries, C. E., Hobolt, S. B, & Walter, S. (2021). Politicizing international cooperation: The mass public, political entrepreneurs, and political opportunity structures. International Organization, 75(2), 306–332.

Dellmuth, L., Scholte, J. A., Tallberg, J., & Verhaegen, S. (2021). The elite-citizen gap in international organization legitimacy. American Political Science Review. Forthcoming.

Dellmuth, L. M., & Scholte, J. P. (2018). Individual Sources of Legitimacy Beliefs: Theory and Data. In Jonas Tallberg Karin Bäckstrand (Eds.) Legitimacy in Global Governance: Sources, Processes, and Consequences. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Dellmuth, L. M., Tallberg, J., & Scholte, J. A. (2019). Institutional sources of legitimacy for international organisations: Beyond procedure versus performance. Review of International Studies, 45(4), 627–646.

Drezner, D. W. (2008). The realist tradition in American public opinion. Perspectives on Politics, 6(1), 51–70.

Druckman, J. N. (2001). On the limits of framing effects: Who can frame? Journal of Politics, 63(4), 1041–1066. https://doi.org/10.1111/0022-3816.00100.

Ghassim, F. (2022). The effects of self-legitimation and delegitimation on public attitudes toward international organizations: A worldwide survey experiment. Presented at the International Studies Association Annual Conference.

Goren, P., Schoen, H., Reifler, J., Scotto, T., & Chittick, W. (2016). A unified theory of value-based reasoning and US public opinion. Political Behavior, 38(4), 977–997.

Gray, J. (2018). Life, Death, or Zombie? The Vitality of International Organizations. International Studies Quarterly, 62(1), 1–13.

Greenhill, B. (2020). How can international organizations shape public opinion? Analysis of a pair of Survey-Based experiments. The Review of International Organizations, 15(3), 165–188.

Guisinger, A., & Saunders, E. (2017). Mapping the boundaries of elite cues: How elites shape mass opinion across international issues. International Studies Quarterly, 61(3), 425–441.

Heinrich, T., Kobayashi, Y., & Bryant, K. A. (2016). Public opinion and foreign aid cuts in economic crises. World Development, 77, 66–79.

Hermann, C. F. (1990). Changing course: When governments choose to redirect foreign policy. International Studies Quarterly, 34(1), 3–21. https://doi.org/10.2307/2600403

Hiel, A. V., & Mervielde, I. (2002). Explaining conservative beliefs and political preferences: A comparison of social dominance orientation and authoritarianism. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 32(5), 965–976.

Hiscox, M. J. (2006). Through a glass and darkly: Attitudes toward international trade and the curious effects of issue framing. International Organization, 60(3), 755–780.

Hurd, I. (1999). Legitimacy and authority in international politics. International Organization, 53(2), 379–408.

Hurst, R., Tidwell, T., & Hawkins, D. (2017). Down the rathole? Public support for US foreign aid. International Studies Quarterly, 61(2), 442–454.

Ikenberry, J. G. (2011). Crisis of the world order. In liberal leviathan: The origins, crisis, and transformation of the American world order, 1–32.

Imai, K., Keele, L., Tingley, D., & Yamamoto, T. (2011). Unpacking the black box of causality: Learning about causal mechanisms from experimental and observational studies. American Political Science Review, 105(4), 765–789.

Johnson, T. (2011). Guilt by association: The link between states’ influence and the legitimacy of intergovernmental organizations. The Review of International Organizations, 6(1), 57–84.

Johnson, T. (2014). Organizational progeny: Why governments are losing control over the proliferating structures of global governance. Transformations in governance. Oxford University Press.

Johnston, A. I. (2008). Social States: China in International Institutions, 1980-2000. Princeton Studies in International History and Politics. Princeton Univ. Press.

Jones, B. (2018). American Sovereignty Is Safe From the UN. Foreign Affairs.

Jost, J. T. (2017). Ideological asymmetries and the essence of political psychology. Political Psychology, 38(2), 167–208. 10.1111/pops.12407.

Kaya, A. (2015). Power and Global Economic Institutions. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Kaya, A., Handlin, S., & Gunaydin, H. (2020). Populism and Voter Attitudes Toward International Organizations: Cross-Country and Experimental Evidence on the International Monetary Fund. Political Economy of International Organization Annual Meeting 2020. https://bit.ly/3hqfdXy.

Keele, L. (2015). Causal mediation analysis: Warning! Assumptions ahead. American Journal of Evaluation, 36(4), 500–513.

Keohane, R. O. (1984). After hegemony: Cooperation and discord in the world political economy. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Kersting, E., & Kilby, C. (2016). With a little help from my friends: Global electioneering and World Bank lending. Journal of Development Economics, 121, 153–165.

Kilby, C. (2009). The political economy of conditionality: An empirical analysis of World Bank loan disbursements. Journal of Development Economics, 89(1), 51–61.

Kilby, C. (2011). Informal influence in the Asian development bank. The Review of International Organizations, 6(3-4), 223.

Kiratli, O. S. (2020). Together or not? Dynamics of public attitudes on UN and NATO. Political Studies, 0032321720956326.

Kiratli, O. S. (2021). Politicization of aiding others: The impact of migration on european public opinion of development aid. Journal of Common Market Studies, 59(1), 53–71.

Kugler, M., Jost, J. T, & Noorbaloochi, S. (2014). Another look at moral foundations theory: Do authoritarianism and social dominance orientation explain liberal-conservative differences in “moral” intuitions?. Social Justice Research, 27(4), 413–431.

Lee, M., & Prather, L. (2020). Selling international law enforcement: elite justifications and public values. Research and Politics Forthcoming.

Lenz, G. S. (2012). Follow the leader? how voters respond to politicians’ policies and performance. In Chicago studies in American politics Chicago. London: The University of Chicago Press.

Lim, D. Y. M., & Vreeland, J. R. (2013). Regional organizations and international politics: Japanese influence over the asian development bank and the UN security council. World Politics, 65(1), 34–72.

Martens, B., Mummert, U., Murrell, P., & Seabright, P. (2002). The institutional economics of foreign aid. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Milner, H. V. (2006). Why multilateralism? foreign aid and domestic Principal-Agent problems. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Milner, H. V., & Dustin, H. (2012). Tingley the choice for multilateralism: Foreign aid and american foreign policy. Review of International Orgnanizations, 8(3), 313–341.

Morse, J. C. (2014). Robert keohane contested multilateralism. Review of International Organizations, 9(4), 385–412.

Mutz, D. C. (2020). Institute for the study of citizens and politics panel study, 2016-2020. https://asc.upenn.edu/research/research-centers/institute-study-citizens-and-politics. Accessed 1 Oct 2022.

Mutz, D. C, & Kim, E. (2017). How ingroup favoritism affects trade preferences. International Organization, 71(4), 827–850.

Novosad, P., & Werker, E. (2014). Who Runs the International System? Power and the Staffing of the United Nations Secretariat.

Pratt, T. (2021). Angling for influence: Institutional proliferation in development banking. International Studies Quarterly, 65(1), 95–108.

Pushter, J. (2016). Favorable views of the UN prevail in Europe, Asia and U.S. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2016/09/20/favorable-views-of-the-un-prevail-in-europe-asia-and-u-s/.

Rathbun, B. C. (2007). Hierarchy and community at home and abroad: Evidence of a common structure of domestic and foreign policy beliefs in american elites. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 51(3), 379–407.

Rathbun, B., Kertzer, J. D., Reifler, J., Goren, P., & Scotto, T. J. (2016). Taking foreign policy preferences seriously: Personal values and foreign policy attitudes. International Studies Quarterly, 60(1), 124–137.

Rho, Sungmin & Michael T. (2017). Why don’t trade preferences reflect economic self-interest? International Organization, 71(S1), S85–S108.

Scheve, Kenneth & David S. (2016). Taxing the rich. In Taxing the Rich. Princeton University Press.

Schlipphak, B., Meiners, P., & Kiratli, O. S. (2022). Crisis Affectedness, Elite Cues and IO Legitimacy. Review of International Organizations, Forthcoming.

Schneider, C. J. (2019). The responsive union: National elections and European governance. Cambridge University Press.

Schwartz, S. H. (2012). An overview of the Schwartz theory of basic values. Online readings in Psychology and Culture, 2(1), 2307–0919. https://doi.org/10.9707/2307-0919.111.

Stone, R. W. (2011). Controlling institutions: International organizations and the global economy. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Tallberg, J., & Zürn, M. (2019). The legitimacy and legitimation of international organizations: introduction and framework. Review of International Organizations, 581–606.

Urpelainen, J., & Van de Graaf, T. (2015). Your place or mine? Institutional capture and the creation of overlapping international institutions. British Journal of Political Science, 45(4), 799–827.

Voeten, E. (2005). The political origins of the UN Security Council’s ability to legitimate the use of force. International Organization, 59(3), 527–557.

Voeten, E. (2020). Populism and backlashes against international courts. Perspectives on Politics, 18(2), 693–724.

von Borzyskowski, I., & Vabulas, F. (2019). Hello, Goodbye: When Do States Withdraw from International Organizations? Review of International Organizations, 14(2), 335–366.

Voss, J. F., & Post, T. A. (1988). On the Solving of Ill-structured Problems. In M. H. Chi, R. Glaser, & M. J. Farr (Eds.) The Nature of Expertise (pp. 261-285). Hillsdale: Erlbaum.

Walter, S. (2021). The backlash against globalization. Annual Review of Political Science, 24, 421–442.

Zaller, J. (1992). The nature and origins of mass opinion. Cambridge [England]. Cambridge University Press.

Zvogbo, K. (2019). Human rights versus national interests: Shifting US public attitudes on the international criminal court. International Studies Quarterly, 63(4), 1065–1078.

Acknowledgements

We thank Don Casler, Lisa Dellmuth, Lindsay Dolan, Noel Johnston, Julia Morse, Tyler Pratt, Jonas Tallberg, Felicity Vabulas, and Noah Zucker for helpful comments on previous drafts. We also thank participants at the 2020 Annual Meeting of the American Political Science Association and 2021 Annual Meetings of the International Studies Association and Political Economy of International Organization conference for constructive feedback. All remaining errors are our own.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Author contributions to research design, analysis, and writing: R.B. 50%, R.C. 50%. The order of the authors is alphabetical.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interests

The authors are not aware of any conflicts of interest related to this research project. The research conducted here complies with the American Political Science Association’s Principles and Guidance for Human Subjects Research. The research was approved by the IRB at the University of California, Berkeley under protocol 2019-07-12427.

Additional information

Responsible editor: Axel Dreher

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Brutger, R., Clark, R. At what cost? Power, payments, and public support of international organizations. Rev Int Organ 18, 431–465 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11558-022-09479-9

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11558-022-09479-9